Abstract

Root rot, a globally devastating disease of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), remains a major constraint on bean production across China. Despite its agricultural impact, the pathogen complex associated with this disease has been poorly characterized in most provinces. To address this critical knowledge gap, we conducted nationwide surveys during 2016–2018, systematically sampling 1–10 symptomatic plants from each of 121 (2016) and 170 (2018) field sites across 17 provinces in China’s major vegetable production regions. Isolates obtained from symptomatic root tissues underwent morphological screening, followed by molecular identification using partial sequences of EF1-α for Fusarium species and ITS regions for other genera. Pathogenicity of representative isolates was subsequently confirmed through controlled greenhouse assays. This integrated approach revealed fourteen fungal and oomycete genera, with Fusarium (predominantly F. oxysporum and F. solani) and Rhizoctonia (R. solani) emerging as the most prevalent pathogens. Notably, pathogen composition exhibited significant regional variation and underwent temporal shifts across developmental stages. Additionally, F. oxysporum, F. solani, and R. solani demonstrated significant interspecies associations with frequent co-occurrence in bean root rot systems. Collectively, this first comprehensive characterization of China’s common bean root rot complex not only clarifies spatial–temporal pathogen dynamics but also provides actionable insights for developing region- and growth stage-specific management strategies, particularly through targeted control of dominant pathogens during key infection windows.

1. Introduction

Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), including both dry bean and green bean varieties, represents the world’s third most economically important edible legume [1,2,3,4]. However, its global production faces significant challenges from root rot, a destructive soil-borne disease [5]. This disease manifests through several characteristic symptoms including seedling mortality, growth stunting, chlorotic foliage, and necrosis of root and vascular systems [6,7]. Depending on disease severity, yield losses can range from 25% to complete crop failure during severe epidemics [5].

The pathogens causing common bean root rot were highly diverse and complex [8,9]. Based on current reports, the major pathogens include fungi and also oomycetes. For pathogenic fungi, the genus Fusarium has the highest number of reported species, including the five pathogens F. solani, F. oxysporum, F. equisetii, F. lateritium, and F. reticulatum [6,10,11]. In addition to Fusarium, other fungal pathogens like Sclerotium spp. [11,12], Alternaria spp. [13], Rhizoctonia solani [10,12], Plectosphaerella cucumerina [14], Macrophomina phaseolina [11], and Colletotrichum spaethianum [15] also have been reported to cause root rot in common bean. Among the documented oomycete pathogens, Aphanomyces euteiches [16] and Pythium spp. are the most frequently reported [10,17,18]. Critically, these pathogens exhibit divergent fungicide sensitivities and epidemiological behaviors. Therefore, understanding the pathogen complex is essential for effective disease management.

Previous studies on the geographical distribution of root rot pathogens in common bean revealed distinct regional patterns (Table A1). Fusarium solani f. sp. phaseoli is the dominant pathogen in Latin America and Africa [19,20], and F. lateritium is the predominant species in Nuevo León, Mexico [21], while more complex multi-pathogen assemblages were observed in several regions: in Iran (F. solani, R. solani, F. oxysporum, Tiarosporella phaseolina, F. equisetii, P. ultimum and P. aphanidermatum [10]), Mexico (F. oxysporum, M. phaseolina, F. solani, F. lateritium and F. reticulatum [11]), and Puerto Rico (F. solani, M. phaseolina, S. rolfsii, P. aphanidermathum, P. graminicola, and R. solani [11]). These findings demonstrate significant variation in pathogen composition across different geographical locations.

China ranks among the world’s leading producers of common beans [22]. However, bean production faces significant threats from root rot disease, with reported yield losses reaching 84% in some regions and complete crop failure in severe cases [23,24]. Despite its economic impact, the pathogen complex causing common bean root rot in China remains poorly characterized. Current understanding relies on fragmented studies, primarily reporting the dominance of F. solani f. sp. phaseoli in localized areas [24,25,26]. Notably, no comprehensive study has systematically investigated the composition and geographical distribution of root rot pathogens across China’s diverse bean-growing regions. This critical knowledge gap continues to impede the development of region-specific, effective control strategies.

To address these critical knowledge gaps, this study was designed with three integrated research objectives: (I) to systematically collect and identify root rot pathogens from common bean across China’s major production regions, (II) to investigate the geographic distribution patterns of predominant pathogen groups, and (III) to comparatively analyze temporal variations in pathogen complex composition throughout different growth stages of common bean.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

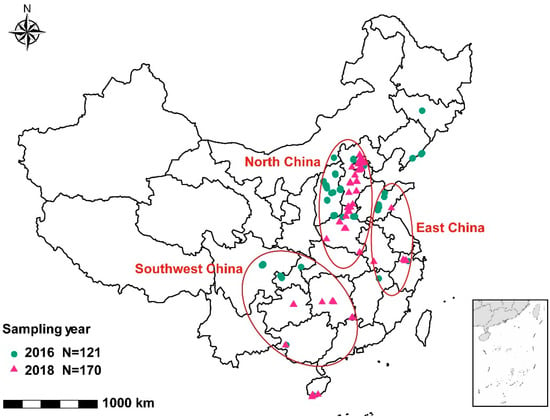

Sampling was conducted across China’s primary vegetable production zones using randomized site selection. During field surveys conducted between 2016 and 2018, 291 symptomatic root samples were collected: 121 samples from 16 provinces in 2016, supplemented by 170 additional samples from 9 provinces in 2018 (Figure 1, Table A2 and Table A3). For each sampling site, the common bean growth stage, classified as seeding (V3–V4: first to third trifoliate leaf fully opened), pod-filing (R7-R8: pod formation to filing), or maturity (R9: physiological maturity) [27], as well as the geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) and elevation (meters above sea level) were documented. Sampling protocols involved carefully excavating 1–10 symptomatic plants per site, gently removing soil from roots, immediately storing specimens in sterile kraft envelopes, transporting them on dry ice, and maintaining samples in a 4 °C refrigerator until pathogen isolation.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of 121 and 170 sampling sites where common bean samples with root rot symptoms were collected in 2016 and 2018, respectively. Five regions, marked with red ellipses, were used for comparing pathogen composition across different locations.

2.2. Isolation and Purification

Root samples were rinsed under tap water for approximately two minutes. For each root system, five to six 1 cm segments were excised from the lesion margins. These fragments were surface sterilized in 1% NaClO for two minutes, followed by three sterile distilled water rinses. After air-drying on sterilized filter paper, fragments were placed on amended potato dextrose agar (PDA, composition per liter: broth of 200 g pilled potato boiled, 20 g dextrose, 18 g agar, and 100 mg streptomycin sulfate and penicillin). Following incubation at 25 °C for 3–5 days, hyphal tips from colony edges were transferred to fresh PDA plates. Isolates were subsequently purified either through single-spore isolation (for sporulating cultures) or single hyphal tip culture (for non-sporulating cultures). For long-term storage, a culture plug from each purified colony was inoculated into 1 mL potato dextrose broth (PDB, PDA without agar) in a 2 mL centrifuge tube. The cultures were grown at 25 °C with 200 rpm shaking for 4–5 days before storage at 4 °C [28].

2.3. Morphological and Molecular Identification

For morphological characterization, each preserved isolate was subcultured by transferring a small mycelial plug onto both water agar (WA, composition per liter: 18 g agar) and potato sucrose agar (PSA, composition per liter: broth of 200 g pilled potato boiled, 20 g sucrose, 18 g agar) plates, followed by incubation at 25 °C for 3–7 days. Initial microscopic examination was performed using a microscope (AxioCam ERc 5s, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) to assess hyphal structures and sporulation morphology. Suspected Fusarium isolates underwent further characterization through culturing on carnation leaf agar (CLA) plates [29], maintained at 25 °C in dark for 7 days. These cultures were then examined under a Carl Zeiss microscope (AxioCam ERc 5s, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany) to observe key diagnostic features including conidial morphology, sporulation structures, and chlamydospore formation. Final morphological identification was conducted following established taxonomic criteria from three authoritative sources: The Fungal Identification Manual, The Fusarium Laboratory Manual, and Chinese Fungal Chronicles [29,30,31].

For further molecular identification, at least two representative isolates per morphologically identified species were randomly selected and cultured on PDA plates until colonies covered two-thirds of the surface. After, mycelia were harvested for DNA extraction using a plant genomic DNA Kit (Tsingke BioTechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) with subsequent storage at −20 °C. The EF-1α gene of Fusarium isolates was amplified using primers EF1/EF2 [32], and the ITS region of other isolates was amplified using universal primers ITS1/ITS4 [33]. The resulting amplicons were sequenced by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and analyzed via NCBI BLAST (version 2.8.1, URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 28 December 2018).

2.4. Pathogenicity Test

To satisfy Koch’s postulate [34], pathogenicity tests were conducted on common bean seeds in greenhouse conditions using 80 representative isolates (minimum 2 per genus/species). To prepare inoculum, intact kernels of uniform size were soaked in double-distilled water for 12 h, sterilized at 121 °C for 30 min, and oven-dried at 80 °C for 2 h [35]. For each isolate, 20 prepared kernels were placed around a mycelial plug on PDA plates, then incubated at 25 °C for 7 days until complete mycelial colonization. The fully colonized wheat kernels were then used as inoculum for subsequent pathogenicity testing.

Common bean seeds (cv. English Red) were surface sterilized in 1% NaClO for two minutes, rinsed three times with sterile distilled water, and soaked in sterile water for 40 min. The sterilized seeds were then sowed in pots (8 cm × 15 cm) containing sterilized soil matrix. For inoculation, one mycelium-colonized wheat kernel was placed adjacent to each seed (one seed per pot, with five pots per replicate and three replicates per isolate), then covered with approximately 3 cm of sterilized soil. Control treatments received sterilized wheat kernels without mycelia. Plants were then maintained in a greenhouse at 25 °C with a 12 h photoperiod for 3–4 weeks before disease evaluation. Root rot severity was assessed using a 0–5 scale [36]: 0 (no symptoms), 1 (light discoloration or 1–10% root surface affected), 2 (heavy discoloration or 11–25% root surface affected), 3 (26–50% root surface affected), 4 (51–75% root surface affected), and 5 (76–100% root surface affected or plant death).

2.5. Data Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (version 3.6.2). Non-parametric analyses were conducted to evaluate differences in disease severity ratings across species. The Kruskal–Wallis test was first performed as an omnibus test to evaluate overall group differences using the kruskal.test function. Following a significant result (p < 0.05), Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni adjustment was conducted for pairwise comparisons between species via the dunn.test function from the dunn.test package (v1.3.5).

To examine geographical and temporal variations in pathogen composition, we categorized isolates into four groups: Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Alternaria, and other minor genera (including 11 additional fungal and oomycete genera). Sampling locations were classified into three geographical regions (North China, East China, and Southwest China; Figure 1 and Table A2). Detection frequency (F) of each pathogen group was calculated as: F = (number of group isolates in region/total region isolates) × 100 [37]. Frequency distribution data were transformed using centered log-ratio (CLR) normalization to address compositional constraints. This was implemented via the transform CLR. function from the RVAideMemoire package (v0.9-83). Overall group differences in CLR-transformed compositional profiles were assessed using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 999 Monte Carlo permutations. Analysis was conducted using the adonis2.function from the vegan package (v2.6-6) with Bray–Curtis dissimilarities. For significant PERMANOVA results (α = 0.05), univariate group differences in individual components were examined using non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests via kruskal.test (stats v4.3.1) and false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment of p-values using the Benjamini–Hochberg method via p.adjust(method = “fdr”).

Given that over 80% of samples yielded multiple major pathogens, potential associations among co-existing species were investigated. For key pathogen pairs (F. oxysporum-F. solani [Fo-Fs], F. oxysporum-R. solani [Fo-Rs], and F. solani-R. solani [Fs-Rs]), chi-square tests of independence (chisq.test) were conducted with the following interpretation framework: p ≥ 0.05: no significant association (accept null hypothesis of independence); p < 0.05 with observed co-occurrence > expected: positive association; p < 0.05 with observed co-occurrence < expected: negative association (antagonism). This analysis revealed whether pathogen pairs tended to co-colonize (positive association), compete (negative association), or occur independently in infected samples.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Isolates from Common Bean Root Rot Samples

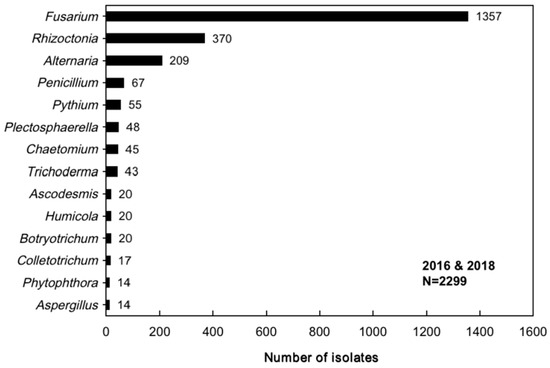

A total of 2299 isolates were obtained from 291 common bean root samples collected between 2016 and 2018. These isolates were identified through combined morphological and molecular characterization as belonging to fourteen genera, namely, Fusarium, Rhizoctonia, Alternaria, Penicillium, Pythium, Plectosphaerella, Chaetomium, Trichoderma, Ascodesmis, Aspergillus, Phytophthora, Colletotrichum, Botryotrichum, and Humicola. The molecular identification details are provided in Table A4. Fusarium was found to be the most predominant genus (59.0% of total isolates), followed by Rhizoctonia (16.1%) and Alternaria (9.1%). The remaining eleven genera were each represented at significantly lower frequencies (≤2.9%), as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The number of isolates per genus obtained from common bean root rot samples collected in China during 2016 and 2018. N represents the total number of identified isolates.

3.2. Pathogenicity and Virulence Test

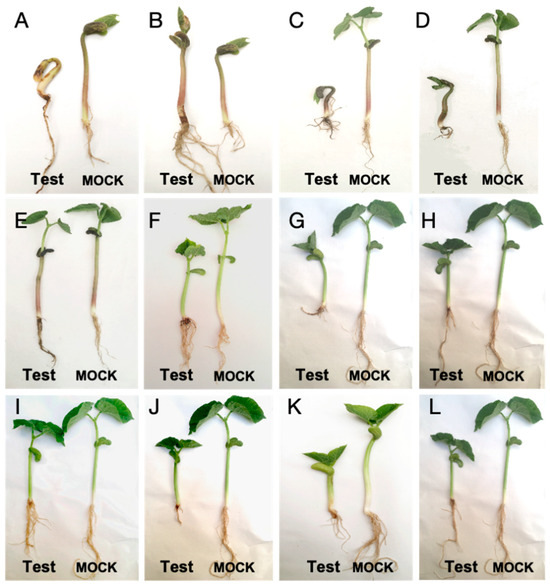

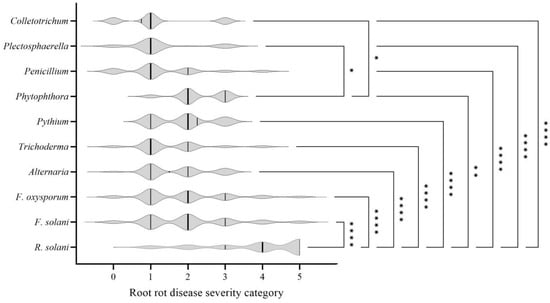

The results of pathogenicity test demonstrated that all 80 tested isolates could cause symptoms on inoculated common bean plants, including seedling death, plant stunting, leaf discoloration, and root rot, which were consistent with symptoms observed under natural field conditions. The original isolates inoculated were re-isolated from these infected plant tissues, while no symptoms were observed in mock-treated plants (Figure 3, Table A5). Significant variation in virulence was detected among pathogens (p < 0.05; Figure 4). R. solani isolates caused extremely higher disease severity than any other pathogens tested (p < 0.01). Phytophthora showed significantly higher virulence than Plectosphaerella spp. and Colletotrichum spp. (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in virulence among the remaining pathogens tested.

Figure 3.

Root rot symptoms on common bean (cv. English Red) following inoculation with different pathogenic isolates. (A,B) Rhizoctonia solani; (C,D) Fusarium oxysporum; (E,F) F. solani; (G) Penicillium spp.; (H) Pythium spp.; (I) Alternaria spp.; (J) Phytophthora spp.; (K) Plectosphaerella spp.; (L) Trichoderma spp. Test: plants inoculated with fungal or oomycete isolates; Mock: plants inoculated with sterile water.

Figure 4.

Virulence analysis of pathogens causing root rot in common bean. For disease severity category data, non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test were performed first, followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test. * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, **** represents p < 0.0001.

3.3. Geographical Distribution of Major Pathogen Groups

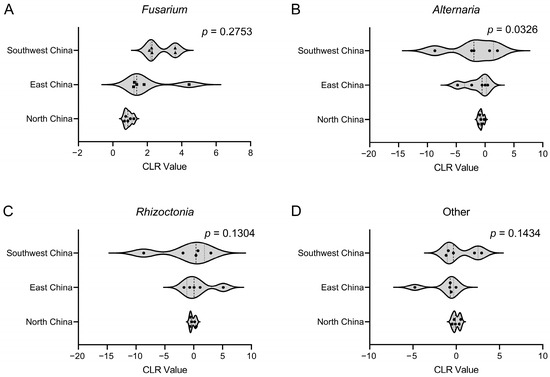

PERMANOVA analysis revealed significant regional variations in pathogen composition across China’s three major production regions [Pr(>F) = 0.002; Table 1]. Fusarium was the dominant genus in all regions, though its isolation frequency showed substantial geographical variation, ranging from 48.6% in North China to 75.9% in Southwest China. In contrast, the isolation frequency distribution of Rhizoctonia across regions falls within a relatively narrow range from 14.8% in Southwest China to 19.6% in East China. The combined other-genera category was most frequent in North China (23.8%) and least common in Southwest China (5.9%). Notably, the frequency distribution of Alternaria, ranging from 3.3% in Southwest China to 12.2% in North China, exhibited significant variation across geographical regions (p < 0.05), whereas no other pathogens showed significant differences in their regional distribution patterns (Figure 5).

Table 1.

Multivariate analysis of variance of frequency distribution of pathogen groups isolated from the common bean root rot samples across different geographical regions.

Figure 5.

Frequency distribution of pathogen groups isolated from the common bean root rot samples across different geographical regions. First, transform the frequency distribution data into CLR (centered log-ratio) values. Then, perform multivariate PERMANOVA analysis to test for overall differences, followed by non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests with false discovery rate correction.

3.4. Regional Variation of Fusarium Species

Four Fusarium species (F. solani, F. oxysporum, F. virguliforme, and F. chlamydosporum) were isolated from all common bean root rot samples. Among these, F. oxysporum (50.9%) and F. solani (44.2%) collectively accounted for 95.1% of all Fusarium isolates, while F. virguliforme and F. chlamydosporum occurred at significantly lower frequencies. Correspondingly, isolation frequencies of the four Fusarium species showed significant variation (χ2 > 100, p < 0.0001; Table 2). The regional analysis revealed both dominant species F. oxysporum and F. solani showed even distribution across regions, however, F. chlamydosporum showed restricted distribution, only detected in North China (Table 2).

Table 2.

Geographic distribution and isolation frequency of Fusarium species in different regions of China.

3.5. Growth Stage-Specific Variation of Major Pathogen Groups

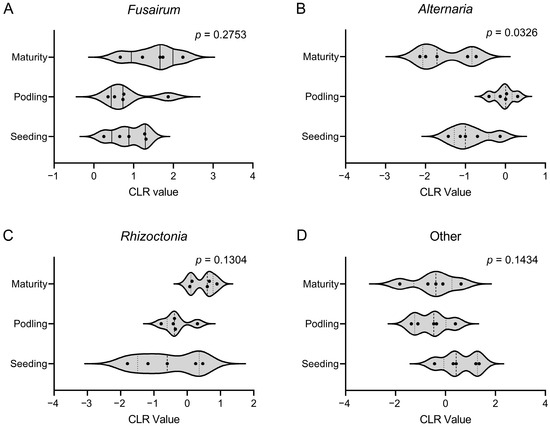

PERMANOVA analysis revealed significant variations in pathogen group frequencies across three growth stages of common bean [Pr(>F) = 0.006; Table 3]. Fusarium maintained dominance at all stages, with its incidence progressively increasing from seedling (46.8%) to maturity (70.0%). Similarly, Rhizoctonia exhibited steady growth stage-dependent increases, initially ranked lowest among groups during seedling (11.7%) and pod-filling (15.0%) stages, but ultimately exceeding both Alternaria and other genera at maturity. On the contrary, the frequency of the combined “other genera” category gradually declined from 26.2% to 9.1%, as the common bean developed. However, only the frequency distribution of Alternaria exhibited significant variations across different growth stages (p < 0.05; Figure 6).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of variance of frequency distribution of pathogen groups isolated from the common bean root rot samples across different growth stages.

Figure 6.

Frequency distribution of pathogen groups isolated from the common bean root rot samples across different growth stages. First, transform the frequency distribution data into CLR (centered log-ratio) values. Then, perform multivariate PERMANOVA analysis to test for overall differences, followed by non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests with false discovery rate correction.

3.6. Growth Stage Variations in Fusarium Species Composition

F. solani and F. oxysporum collectively accounted for over 95% of Fusarium isolates across all growth stages, demonstrating clear dominance. Correspondingly, isolation frequencies of the four Fusarium species showed significant variation in each growth stage (p < 0.0001; Table 4). However, the frequencies of each Fusarium species showed no significant differences across different growth stages (p > 0.05; Table 4).

Table 4.

Abundance and isolation frequency of Fusarium species at different growth stages.

3.7. Pathogen Co-Occurrence in Bean Root Rot

Statistical analysis revealed significant species associations among F. oxysporum, R. solani, and F. solani (p < 0.001; Table 5). The observed co-occurrence patterns consistently exceeded theoretical expectations under random distribution assumptions. The observed co-occurrence of F. oxysporum–F. solani, F. oxysporum–R. solani, and F. solani–R. solani significantly exceeded theoretical random distribution values. In contrast, isolated occurrences of any single pathogen consistently fell below expected values. Simultaneous absence of pathogen pairs also occurred more frequently than predicted. These consistent patterns across all tested species combinations suggest strong ecological interactions among these dominant root rot pathogens.

Table 5.

Statistical analysis of pairwise co-infections between F. oxysporum, F. solani, and R. solani based on root infection frequencies.

4. Discussion

This study presented the first systematic characterization of the pathogen composition associated with common bean root rot across major production regions in China, addressing critical knowledge gaps in geographical distribution and growth-stage dynamics. Our investigation revealed a diverse 14-genus pathogen complex dominated by Fusarium (59.0%) and Rhizoctonia (16.1%), with nine novel pathogen identifications expanding global understanding of legume root rot etiology. Among them, F. virguliforme and F. chlamydosporum were newly confirmed as causal agents alongside seven previously unreported genera, namely, Chaetomium, Trichoderma, Ascodesmis, Aspergillus, Phytophthora, Botryotrichum, and Humicola [5,12,13,38]. Notably, R. solani exhibited significantly higher virulence than any other pathogens. These findings significantly broaden the known taxonomic diversity of bean root rot pathogens beyond existing worldwide reports, providing crucial insights for disease management strategies.

Significant regional variations in major pathogen group frequencies were observed across China’s three production regions, reflecting distinct environmental influences. Fusarium was dominant in all regions without significant variations, and the most virulent Rhizoctonia exhibited similar isolation frequency distribution in all regions too, while Alternaria showed significant variation across geographical regions. These patterns aligned with global reports of pathogen heterogeneity, such as F. solani f. sp. phaseoli dominance in Latin America and Africa [19,20,39,40] or F. lateritium in Mexico [21]. Regional climate, soil properties, and agronomic practices collectively shaped pathogen communities [41,42,43], underscoring the need for region-specific management strategies. At the species level, F. oxysporum and F. solani collectively accounted for > 95% of Fusarium isolates but displayed contrasting distributions. F. oxysporum dominated East and Southwest China, whereas F. solani prevailed in North China. Such divergence might reflect adaptations to local soil conditions or host genotypes, as reported previously [11,40,44].

Significant shifts in pathogen composition were observed across common bean growth stages, revealing distinct temporal dynamics. Fusarium prevalence progressively increased from seedling to maturity, consistent with its role as a primary root rot pathogen [10,11,45,46]. Species-level analysis revealed F. oxysporum dominated early stages (seedling to pod-filling), aligning with its association with seedling diseases [6,47,48], while F. solani increased at maturity, likely due to cumulative colonization [28]. Concurrently, Rhizoctonia frequencies exhibited growth stage-dependent escalation, surpassing other genera by maturity, potentially reflecting declining host resistance or pathogen accumulation [49]. Although these temporal patterns were derived from national-scale data, regional-scale investigations of developmental stage-associated pathogen community dynamics would enhance the development of targeted management strategies. These temporal dynamics underscore the necessity for stage-specific management strategies targeting dominant pathogens during critical developmental phases.

A key finding was that any two of the three species F. solani, F. oxysporum, and R. solani showed significant positive associations and frequently co-occurred in diseased roots, though all three rarely appeared simultaneously. This synergy might result from either shared environmental preferences (e.g., high nitrogen availability or specific soil microbiome conditions) or facilitated infection, whereby initial colonization by one pathogen modifies root physiology to benefit subsequent infections [38,43]. Further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of these interactions and develop integrated control strategies targeting these co-occurring pathogens.

Our study establishes a scientific foundation for targeted root rot management in China. The documented regional variations and growth-stage dynamics of pathogens support the need for location-specific strategies, such as deploying resistant cultivars tailored to dominant local species or timing control measures to critical growth phases [9,50]. Additionally, the frequent co-occurrence of major pathogens (F. solani, F. oxysporum, and R. solani) underscored the necessity of integrated management measures, such as soil amendments to disrupt pathogen synergies, rather than single-species targeting [50,51].

To enhance root rot management, further work should characterize the virulence diversity within key pathogenic species, investigate soil microbiome-mediated modulation of pathogen interactions, and validate region-specific and growth stage-adapted control strategies through field trials. Such efforts will provide the scientific basis for developing sustainable, precision-based management approaches against this economically devastating disease.

5. Conclusions

Nationwide surveys identified Fusarium (F. oxysporum, F. solani) and Rhizoctonia (R. solani) as the dominant pathogens causing common bean root rot in China, with 14 fungal and oomycete genera detected. Pathogen composition varied regionally and across growth stages, with these key species showing high virulence and frequent co-infection. This first comprehensive study provides critical insights for developing targeted, region- and growth stage-specific control strategies to manage this devastating disease.

Author Contributions

L.Y.: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, and writing—original draft. X.-H.L.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and writing—review and editing. B.-M.W.: investigation, supervision, and writing—review and editing. Z.-M.Z.: investigation. S.-D.L.: conceptualization and resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the China Agricultural Research System (CARS-23-C04) and the Special Project of Ministry of Agriculture (201503112-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors highly appreciate the assistance of Lu Xiao in the sampling activity.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Zeng-Ming Zhong was employed by the company Beijing Qigao Biologics Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Worldwide pathogens causing root rot in common beans and their geographic distribution.

Table A1.

Worldwide pathogens causing root rot in common beans and their geographic distribution.

| Fungal Pathogen (Genus/Species) | Main Legume Crop Hosts | Primary Symptoms | Geographic Distribution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. solani | P. vulgaris, Glycine max, Vigna unguiculata | Foot and root rot, vascular wilting | Latin America, North America (Puerto Rico), Africa, Asia (Iran) | [6,10,11] |

| Fusarium solani f. sp. phaseoli | P. vulgaris | Root rot, vascular wilting | Americas (United States, Puerto Rico, Spain), Africa, Asia | [19,20] |

| F. oxysporum | G. max, P. vulgaris, V. unguiculata | Root rot, vascular browning | Latin America, Africa, Asia (Iran) | [10] |

| F. equisetii | G. max, P. vulgaris | Foot and root rot | Asia (Iran) | [10] |

| F. lateritium | P. vulgaris, Pisum sativum | Root rot | North America (Mexico), Asia | [19] |

| F. reticulatum | G. max, P. vulgaris | Root rot | North America (Puerto Rico), Asia | [11] |

| Sclerotium spp. | G. max, P. vulgaris, V. unguiculata | Foot and root rot | Africa (Uganda) | [11,12] |

| Alternaria spp. | P. vulgaris | Root rot | Africa (Tunisia) | [13] |

| Rhizoctonia solani | G. max, P. vulgaris, P. sativum | Root rot, damping-off | North America (Puerto Rico), Asia (Iran), Africa (Uganda) | [10,12] |

| Plectosphaerella cucumerina | P. vulgaris | Root rot | Asia (China) | [14] |

| Macrophomina phaseolina | P. vulgaris | Dry root rot | North America (Puerto Rico), Asia | [11] |

| Colletotrichum spaethianum | P. vulgaris | Root rot | Asia (China) | [15] |

| Aphanomyces euteiches | P. sativum, P. vulgaris | Root rot | Americas (United States), Europe | [16] |

| Pythium spp. | P. vulgaris, V. unguiculata, P. sativum | Foot and root rot | South America (Spain), Europe, Asia (Iran) | [11,17,18] |

| Tiarosporella phaseolina | P. vulgaris, Medicago sativa | Dry wilt and foot rot | Asia (Iran), Americas | [10] |

Table A2.

Common bean root rot samples collected from each province in China during this study.

Table A2.

Common bean root rot samples collected from each province in China during this study.

| Region | Province | City/ | County | Village | Stage | Number of Samples | Roots per Site | Total Roots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | ||||||||

| North China | Shanxi | 5 | 14 | 16 | R7–R9 | 30 | 5 | 150 |

| Neimenggu | 1 | 1 | 2 | V3–V4 | 2 | 5 | 10 | |

| Henan | 8 | 9 | 24 | V3–V4; R7–R9 | 30 | 2–5 | 128 | |

| Hebei | 10 | 16 | 29 | V3–V4; R7–R9 | 45 | 1–8 | 182 | |

| Beijing | 7 | 7 | 44 | V3–V4; R7–R9 | 58 | 3–6 | 200 | |

| East China | Zhejiang | 1 | 2 | 5 | V3–V4; R7–R8 | 7 | 4–18 | 47 |

| Shandong | 5 | 13 | 13 | R9 | 13 | 10 | 81 | |

| Jiangxi | 1 | 1 | 1 | R9 | 1 | 5 | 5 | |

| Anhui | 1 | 1 | 1 | R7–R8 | 1 | 10 | 10 | |

| Southwest China | Sichuan | 3 | 10 | 21 | R9 | 36 | 10 | 360 |

| Chongqing | 3 | 5 | 14 | R9 | 21 | 10 | 210 | |

| Guangxi | 1 | 1 | 2 | R7–R9 | 2 | 7 | 14 | |

| Guizhou | 1 | 1 | 5 | V3–V4; R7–R8 | 12 | 2–6 | 35 | |

| Hunan | 3 | 8 | 12 | V3–V4 | 12 | 4–10 | 77 | |

| - | Liaoning | 3 | 4 | 5 | R9 | 9 | 5 | 45 |

| - | Hainan | 1 | 1 | 5 | V3–V4; R7–R9 | 11 | 3–7 | 53 |

| - | Jilin | 1 | 1 | 1 | R9 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| - | Total | 55 | 95 | 200 | - | 291 | - | 1612 |

Notes: V = vegetative; R = reproductive; V3–V4: from the first trifoliate leaf fully opened to the third trifoliate opened; R7–R8: from pod formation to pod-filing; R9: physiological maturity.

Table A3.

The latitude and longitude information of the sampling sites.

Table A3.

The latitude and longitude information of the sampling sites.

| Sample No. | Sampling Province | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shanxi | 39.31020 | 113.18628 |

| 2 | Shanxi | 39.41713 | 113.17947 |

| 3 | Shanxi | 39.40783 | 113.15060 |

| 4 | Shanxi | 38.39267 | 111.94016 |

| 5 | Shanxi | 38.80105 | 111.66961 |

| 6 | Shanxi | 38.76749 | 111.61128 |

| 7 | Shanxi | 38.39197 | 111.86366 |

| 8 | Shanxi | 38.28847 | 111.97351 |

| 9 | Shanxi | 38.35871 | 111.93238 |

| 10 | Shanxi | 38.38697 | 111.87569 |

| 11 | Shanxi | 38.40367 | 111.87566 |

| 12 | Shanxi | 38.21078 | 111.93782 |

| 13 | Shanxi | 38.10853 | 111.99765 |

| 14 | Shanxi | 37.84183 | 113.52763 |

| 15 | Shanxi | 37.85327 | 113.61473 |

| 16 | Shanxi | 37.85450 | 113.63106 |

| 17 | Shanxi | 37.93801 | 113.60275 |

| 18 | Shanxi | 37.80781 | 113.62741 |

| 19 | Shanxi | 35.47936 | 112.63339 |

| 20 | Shanxi | 35.47436 | 112.61046 |

| 21 | Shanxi | 35.40627 | 112.47092 |

| 22 | Shanxi | 35.48027 | 112.49632 |

| 23 | Shanxi | 35.47671 | 112.52754 |

| 24 | Shanxi | 37.65262 | 112.70026 |

| 25 | Shanxi | 36.98486 | 111.89460 |

| 26 | Shanxi | 37.92152 | 113.62477 |

| 27 | Shanxi | 36.93915 | 111.90385 |

| 28 | Shanxi | 37.62325 | 112.52692 |

| 29 | Shanxi | 37.62237 | 112.54632 |

| 30 | Shanxi | 37.61422 | 112.46373 |

| 31 | Neimenggu | 40.93680 | 113.20556 |

| 32 | Neimenggu | 40.60025 | 115.63154 |

| 33 | Henan | 35.24107 | 113.52763 |

| 34 | Henan | 31.70716 | 115.13929 |

| 35 | Henan | 36.06631 | 114.32032 |

| 36 | Henan | 36.06601 | 114.32383 |

| 37 | Henan | 36.06714 | 114.32445 |

| 38 | Henan | 36.06712 | 114.32716 |

| 39 | Henan | 36.06746 | 114.32547 |

| 40 | Henan | 36.06569 | 114.32688 |

| 41 | Henan | 36.06366 | 114.32721 |

| 42 | Henan | 36.06117 | 114.33316 |

| 43 | Henan | 36.05825 | 114.33391 |

| 44 | Henan | 36.04255 | 114.34251 |

| 45 | Henan | 35.28853 | 114.02144 |

| 46 | Henan | 35.25991 | 114.03001 |

| 47 | Henan | 35.24929 | 114.04027 |

| 48 | Henan | 35.23720 | 114.03345 |

| 49 | Henan | 34.76818 | 113.24252 |

| 50 | Henan | 34.79415 | 113.20285 |

| 51 | Henan | 35.67050 | 114.29795 |

| 52 | Henan | 35.72525 | 114.34031 |

| 53 | Henan | 35.69275 | 114.36139 |

| 54 | Henan | 35.65642 | 114.35042 |

| 55 | Henan | 35.66290 | 114.40715 |

| 56 | Henan | 35.72135 | 114.42521 |

| 57 | Henan | 35.75791 | 114.41259 |

| 58 | Henan | 35.68262 | 114.41416 |

| 59 | Henan | 33.27565 | 111.56088 |

| 60 | Henan | 34.09981 | 113.85962 |

| 61 | Henan | 34.11798 | 113.70382 |

| 62 | Henan | 36.15724 | 114.41963 |

| 63 | Hebei | 40.51939 | 115.60522 |

| 64 | Hebei | 39.81131 | 116.81117 |

| 65 | Hebei | 39.59364 | 116.54935 |

| 66 | Hebei | 39.59364 | 116.54935 |

| 67 | Hebei | 39.82800 | 115.40550 |

| 68 | Hebei | 39.82800 | 115.40560 |

| 69 | Hebei | 39.82000 | 115.40190 |

| 70 | Hebei | 39.82000 | 115.40190 |

| 71 | Hebei | 39.82000 | 115.40190 |

| 72 | Hebei | 39.82800 | 115.40550 |

| 73 | Hebei | 39.82985 | 115.40976 |

| 74 | Hebei | 39.04724 | 115.65895 |

| 75 | Hebei | 39.04666 | 115.66029 |

| 76 | Hebei | 39.04436 | 115.65932 |

| 77 | Hebei | 38.43967 | 114.97497 |

| 78 | Hebei | 38.41491 | 114.96345 |

| 79 | Hebei | 38.34450 | 114.96623 |

| 80 | Hebei | 38.34595 | 114.96477 |

| 81 | Hebei | 36.33047 | 114.96307 |

| 82 | Hebei | 38.32317 | 114.96325 |

| 83 | Hebei | 38.32317 | 114.96325 |

| 84 | Hebei | 38.32317 | 114.96325 |

| 85 | Hebei | 37.46296 | 114.66158 |

| 86 | Hebei | 37.46664 | 114.67618 |

| 87 | Hebei | 37.46661 | 114.67642 |

| 88 | Hebei | 37.52309 | 115.57732 |

| 89 | Hebei | 37.51004 | 115.57800 |

| 90 | Hebei | 37.50952 | 115.58409 |

| 91 | Hebei | 37.51305 | 115.59563 |

| 92 | Hebei | 37.51468 | 115.59662 |

| 93 | Hebei | 37.51740 | 115.60588 |

| 94 | Hebei | 38.45041 | 115.79375 |

| 95 | Hebei | 38.40530 | 115.80514 |

| 96 | Hebei | 38.42277 | 115.75369 |

| 97 | Hebei | 38.42602 | 115.75132 |

| 98 | Hebei | 38.42508 | 115.75149 |

| 99 | Hebei | 38.45985 | 115.76659 |

| 100 | Hebei | 38.45985 | 115.76659 |

| 101 | Hebei | 39.46110 | 116.20728 |

| 102 | Hebei | 39.46115 | 116.20642 |

| 103 | Hebei | 39.46064 | 116.20638 |

| 104 | Hebei | 39.46064 | 116.20638 |

| 105 | Hebei | 39.45913 | 116.20924 |

| 106 | Hebei | 39.45918 | 116.21256 |

| 107 | Hebei | 39.45918 | 116.21256 |

| 108 | Beijing | 40.13645 | 116.17446 |

| 109 | Beijing | 40.10151 | 116.22118 |

| 110 | Beijing | 40.02956 | 116.28713 |

| 111 | Beijing | 40.02956 | 116.28713 |

| 112 | Beijing | 40.03739 | 116.27167 |

| 113 | Beijing | 40.04535 | 116.30024 |

| 114 | Beijing | 40.02956 | 116.28713 |

| 115 | Beijing | 40.02956 | 116.28713 |

| 116 | Beijing | 40.02956 | 116.28713 |

| 117 | Beijing | 40.02956 | 116.28713 |

| 118 | Beijing | 40.02956 | 116.28713 |

| 119 | Beijing | 40.02956 | 116.28713 |

| 120 | Beijing | 40.10151 | 116.22118 |

| 121 | Beijing | 40.10151 | 116.22118 |

| 122 | Beijing | 40.02884 | 116.29159 |

| 123 | Beijing | 40.02884 | 116.29159 |

| 124 | Beijing | 40.02884 | 116.29159 |

| 125 | Beijing | 40.02884 | 116.29159 |

| 126 | Beijing | 40.02884 | 116.29159 |

| 127 | Beijing | 40.15390 | 116.58520 |

| 128 | Beijing | 40.20290 | 116.58460 |

| 129 | Beijing | 40.22170 | 116.57330 |

| 130 | Beijing | 40.21584 | 116.60732 |

| 131 | Beijing | 40.24363 | 116.65337 |

| 132 | Beijing | 40.24527 | 116.63536 |

| 133 | Beijing | 40.27652 | 116.63219 |

| 134 | Beijing | 40.28004 | 116.62683 |

| 135 | Beijing | 40.36181 | 116.76081 |

| 136 | Beijing | 40.22410 | 116.46140 |

| 137 | Beijing | 40.22540 | 116.54210 |

| 138 | Beijing | 40.22200 | 116.57140 |

| 139 | Beijing | 39.66237 | 116.53007 |

| 140 | Beijing | 39.65502 | 116.35959 |

| 141 | Beijing | 39.63912 | 116.47253 |

| 142 | Beijing | 39.64164 | 116.43046 |

| 143 | Beijing | 39.61289 | 116.49752 |

| 144 | Beijing | 39.66664 | 116.52510 |

| 145 | Beijing | 39.65841 | 116.53228 |

| 146 | Beijing | 39.62822 | 116.56745 |

| 147 | Beijing | 39.61253 | 116.41731 |

| 148 | Beijing | 40.11570 | 117.03000 |

| 149 | Beijing | 40.10250 | 116.58490 |

| 150 | Beijing | 40.91300 | 116.59100 |

| 151 | Beijing | 40.43300 | 116.59210 |

| 152 | Beijing | 40.45300 | 116.52350 |

| 153 | Beijing | 40.35100 | 116.51400 |

| 154 | Beijing | 40.34500 | 116.90450 |

| 155 | Beijing | 40.06725 | 116.77033 |

| 156 | Beijing | 40.07140 | 116.75619 |

| 157 | Beijing | 39.61300 | 116.41226 |

| 158 | Beijing | 39.57070 | 116.35904 |

| 159 | Beijing | 39.55734 | 116.44816 |

| 160 | Beijing | 39.53778 | 116.32705 |

| 161 | Beijing | 39.59258 | 116.33069 |

| 162 | Beijing | 39.66014 | 116.54935 |

| 163 | Beijing | 39.57573 | 116.49532 |

| 164 | Beijing | 39.59324 | 116.33205 |

| 165 | Beijing | 39.56887 | 116.49686 |

| 166 | Zhejiang | 30.18900 | 120.26564 |

| 167 | Zhejiang | 30.24832 | 120.06353 |

| 168 | Zhejiang | 30.25751 | 119.97864 |

| 169 | Zhejiang | 30.28404 | 120.13571 |

| 170 | Zhejiang | 30.25176 | 120.07564 |

| 171 | Zhejiang | 30.25176 | 120.07564 |

| 172 | Zhejiang | 30.41065 | 119.83784 |

| 173 | Shandong | 36.60327 | 118.68391 |

| 174 | Shandong | 36.95311 | 118.82176 |

| 175 | Shandong | 35.48044 | 117.72460 |

| 176 | Shandong | 35.46022 | 117.68366 |

| 177 | Shandong | 35.58332 | 117.64191 |

| 178 | Shandong | 35.73337 | 117.91193 |

| 179 | Shandong | 35.61296 | 117.65528 |

| 180 | Shandong | 35.46193 | 117.74347 |

| 181 | Shandong | 35.97355 | 117.89570 |

| 182 | Shandong | 35.95890 | 117.90614 |

| 183 | Shandong | 35.15014 | 114.93485 |

| 184 | Shandong | 35.16870 | 114.75342 |

| 185 | Shandong | 35.14053 | 114.98570 |

| 186 | Jiangxi | 28.99013 | 116.81879 |

| 187 | Anhui | 30.63887 | 116.58448 |

| 188 | Sichuan | 31.12368 | 104.21607 |

| 189 | Sichuan | 31.11764 | 104.21550 |

| 190 | Sichuan | 31.11689 | 104.21462 |

| 191 | Sichuan | 31.11663 | 104.21406 |

| 192 | Sichuan | 31.11382 | 104.21097 |

| 193 | Sichuan | 31.11443 | 104.20951 |

| 194 | Sichuan | 31.01974 | 104.17745 |

| 195 | Sichuan | 31.09836 | 104.27236 |

| 196 | Sichuan | 31.10045 | 104.27108 |

| 197 | Sichuan | 31.10554 | 104.27395 |

| 198 | Sichuan | 31.10802 | 104.26935 |

| 199 | Sichuan | 31.11207 | 104.26560 |

| 200 | Sichuan | 31.11570 | 104.26127 |

| 201 | Sichuan | 31.11973 | 104.26169 |

| 202 | Sichuan | 31.12024 | 104.25909 |

| 203 | Sichuan | 31.12310 | 104.25439 |

| 204 | Sichuan | 31.12724 | 104.24940 |

| 205 | Sichuan | 31.12561 | 104.24385 |

| 206 | Sichuan | 31.02630 | 104.16052 |

| 207 | Sichuan | 31.01499 | 104.16545 |

| 208 | Sichuan | 31.01655 | 104.16694 |

| 209 | Sichuan | 31.01916 | 104.17009 |

| 210 | Sichuan | 31.01683 | 104.12060 |

| 211 | Sichuan | 31.01857 | 104.12406 |

| 212 | Sichuan | 31.01778 | 104.12712 |

| 213 | Sichuan | 31.01756 | 104.12735 |

| 214 | Sichuan | 31.01533 | 104.13420 |

| 215 | Sichuan | 31.01524 | 104.13410 |

| 216 | Sichuan | 31.01530 | 104.13946 |

| 217 | Sichuan | 31.01916 | 104.17010 |

| 218 | Sichuan | 31.01524 | 104.13410 |

| 219 | Sichuan | 31.12992 | 104.23796 |

| 220 | Sichuan | 31.00541 | 104.15568 |

| 221 | Sichuan | 31.02283 | 104.10629 |

| 222 | Sichuan | 31.01914 | 104.10843 |

| 223 | Sichuan | 31.10351 | 104.20873 |

| 224 | Chongqing | 30.77011 | 108.43954 |

| 225 | Chongqing | 30.00016 | 106.12687 |

| 226 | Chongqing | 29.99863 | 106.12575 |

| 227 | Chongqing | 29.99859 | 106.13578 |

| 228 | Chongqing | 29.99780 | 106.14043 |

| 229 | Chongqing | 29.99556 | 106.14550 |

| 230 | Chongqing | 29.99355 | 106.15266 |

| 231 | Chongqing | 29.99187 | 106.16047 |

| 232 | Chongqing | 29.98706 | 106.16505 |

| 233 | Chongqing | 29.98706 | 106.16506 |

| 234 | Chongqing | 29.78785 | 106.28156 |

| 235 | Chongqing | 29.79203 | 106.28292 |

| 236 | Chongqing | 29.79315 | 106.28454 |

| 237 | Chongqing | 29.79113 | 106.27917 |

| 238 | Chongqing | 29.79970 | 106.28218 |

| 239 | Chongqing | 29.80803 | 106.28344 |

| 240 | Chongqing | 29.80283 | 106.28382 |

| 241 | Chongqing | 29.80220 | 106.28448 |

| 242 | Chongqing | 29.80153 | 106.28524 |

| 243 | Chongqing | 29.80177 | 106.28537 |

| 244 | Chongqing | 29.98706 | 106.16505 |

| 245 | Guangxi | 23.32623 | 106.61212 |

| 246 | Guangxi | 23.32899 | 106.62158 |

| 247 | Guizhou | 27.21687 | 107.57111 |

| 248 | Guizhou | 27.21687 | 107.57111 |

| 249 | Guizhou | 27.21687 | 107.57111 |

| 250 | Guizhou | 27.21687 | 107.57111 |

| 251 | Guizhou | 27.22345 | 107.55065 |

| 252 | Guizhou | 27.21676 | 107.57098 |

| 253 | Guizhou | 27.20031 | 107.54578 |

| 254 | Guizhou | 27.20154 | 107.54572 |

| 255 | Guizhou | 27.18461 | 107.58902 |

| 256 | Guizhou | 27.20154 | 107.54572 |

| 257 | Guizhou | 27.20154 | 107.54572 |

| 258 | Guizhou | 27.22196 | 107.55738 |

| 259 | Hunan | 27.28936 | 110.60734 |

| 260 | Hunan | 25.54479 | 113.65578 |

| 261 | Hunan | 25.54967 | 113.60865 |

| 262 | Hunan | 25.55936 | 113.69013 |

| 263 | Hunan | 25.55982 | 113.71602 |

| 264 | Hunan | 27.31478 | 111.715872 |

| 265 | Hunan | 27.22257 | 111.83645 |

| 266 | Hunan | 27.31478 | 111.71587 |

| 267 | Hunan | 27.31478 | 111.71587 |

| 268 | Hunan | 27.23382 | 111.83068 |

| 269 | Hunan | 27.29494 | 111.76303 |

| 270 | Hunan | 27.27205 | 111.69587 |

| 271 | Liaoning | 39.68004 | 122.89789 |

| 272 | Liaoning | 39.71416 | 122.97196 |

| 273 | Liaoning | 39.88909 | 124.09901 |

| 274 | Liaoning | 39.69624 | 122.93206 |

| 275 | Liaoning | 39.96288 | 124.22381 |

| 276 | Liaoning | 39.97018 | 124.24395 |

| 277 | Liaoning | 39.94946 | 124.18820 |

| 278 | Liaoning | 39.92736 | 124.12458 |

| 279 | Liaoning | 39.93187 | 124.15184 |

| 280 | Hainan | 18.41188 | 109.18473 |

| 281 | Hainan | 18.21360 | 109.10200 |

| 282 | Hainan | 18.36091 | 109.19870 |

| 283 | Hainan | 18.35456 | 109.20054 |

| 284 | Hainan | 18.21310 | 109.10550 |

| 285 | Hainan | 18.36428 | 109.19153 |

| 286 | Hainan | 18.41762 | 109.71702 |

| 287 | Hainan | 18.21360 | 109.10500 |

| 288 | Hainan | 18.24500 | 109.12230 |

| 289 | Hainan | 18.22130 | 109.10590 |

| 290 | Hainan | 18.35728 | 109.17184 |

| 291 | Jilin | 43.85878 | 125.54167 |

Table A4.

Genetic identification of representative pathogenic isolates.

Table A4.

Genetic identification of representative pathogenic isolates.

| Strain No. | GenBank Accession No. | Gene | Genus or Species | Top Match (Accession) | Identity (%) | Query Cover (%) | E-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt1 | OK067695 | ITS | Alternaria sp. | MT951215.1 | 99.6 | 99 | 0.0 |

| AltSX241 | OK330459 | ITS | Alternaria sp. | OR964412.2 | 100 | 98 | 0.0 |

| FSSC129 | OK330460 | ITS | Fusarium solani | OR123272.1 | 100 | 98 | 0.0 |

| FSSX2571 | OK330461 | ITS | F. solani | PV383491.1 | 100 | 98 | 0.0 |

| FSCQ215 | OK330462 | ITS | F. solani | PV383491.1 | 100 | 98 | 0.0 |

| FVCQ231 | OK330463 | ITS | F. virguliforme | MZ854210.1 | 99.4 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FVSD211 | OK330464 | ITS | F. virguliforme | MZ854209.1 | 98.3 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FCSX567 | OK330465 | ITS | F. chlamydosporum | ON242166.1 | 99.4 | 99 | 0.0 |

| RSCQ236 | OK330466 | ITS | Rhizoctonia solani | OL873284.1 | 99.7 | 100 | 0.0 |

| RSSC2244 | OK330467 | ITS | R. solani | OL873284.1 | 99.4 | 100 | 0.0 |

| PenLN2522 | OK330468 | ITS | Penicillium sp. | KP900325.1 | 99.1 | 100 | 0.0 |

| PytSC255 | OK330469 | ITS | Pythium sp. | KJ162354.1 | 99.8 | 99 | 0.0 |

| Plec1 | OK330470 | ITS | Plectosphaerella sp. | OR654246.1 | 99.4 | 99 | 0.0 |

| Chae1 | OK330471 | ITS | Chaetomium sp. | MZ363862.1 | 99.4 | 96 | 0.0 |

| TriSX5531 | OK330472 | ITS | Trichoderma sp. | OK175851.1 | 99.7 | 100 | 0.0 |

| ASCO1 | OK330473 | ITS | Ascodesmis sp. | MZ221602.1 | 99.8 | 100 | 0.0 |

| Humi1 | OK330474 | ITS | Humicola sp. | MW199085.1 | 99.4 | 99 | 0.0 |

| Botry1 | OK330475 | ITS | Botryotrichum sp. | MG770259.1 | 99.0 | 98 | 0.0 |

| Col1 | OK330476 | ITS | Colletotrichum sp. | ON427165.1 | 99.8 | 100 | 0.0 |

| PhyCQ3681 | OK330477 | ITS | Phytophthora sp. | PP783476.1 | 99.5 | 100 | 0.0 |

| Asp1 | OK330478 | ITS | Aspergillus sp. | NR_131292.1 | 99.8 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FOSX2933 | OR066400 | EF1α | F. oxysporum | MG735692.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FOSX2731 | OR083083 | EF1α | F. oxysporum | HM057313.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FOCQ3871 | OR083084 | EF1α | F. oxysporum | OQ130020.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FOSC1110 | OR083085 | EF1α | F. oxysporum | MH698997.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FOCQ3823 | OR083086 | EF1α | F. oxysporum | OQ130020.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FOSC289 | OR083087 | EF1α | F. oxysporum | MW438342.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FOSC1461 | OR083088 | EF1α | F. oxysporum | MW438342.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FOSC1331 | OR083089 | EF1α | F. oxysporum | PQ654043.1 | 99.7 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FSSX2163 | OR083090 | EF1α | F. solani | MN977911.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FSSX2451 | OR083091 | EF1α | F. solani | OQ511067.1 | 99.9 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FSCQ2422 | OR083092 | EF1α | F. solani | OP184956.1 | 99.7 | 100 | 0.0 |

| FSCQ31042 | OR083093 | EF1α | F. solani | ON366424.1 | 100.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

Table A5.

Virulence evaluation of representative isolates for each species obtained.

Table A5.

Virulence evaluation of representative isolates for each species obtained.

| Species | No. of Plants for Each Disease Severity Category | Total of Plants Inoculated | Total of Isolates Tested | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| R. solani | 2 | 15 | 22 | 21 | 48 | 74 | 182 | 13 |

| F. solani | 15 | 73 | 80 | 39 | 21 | 12 | 240 | 17 |

| F. oxysporum | 19 | 110 | 85 | 48 | 23 | 12 | 297 | 20 |

| Alternaria | 1 | 14 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 2 |

| Trichoderma | 2 | 15 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 30 | 2 |

| Pythium spp. | 0 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 2 |

| Phytophthora spp. | 0 | 3 | 15 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 2 |

| Penicillium spp. | 5 | 14 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 29 | 2 |

| Plectosphaerella spp. | 3 | 18 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 2 |

| Colletotrichum spp. | 6 | 14 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 2 |

References

- Wang, L.; Cao, Y.; Wang, E.T.; Qiao, Y.J.; Jiao, S.; Liu, Z.S.; Zhao, L.; Wei, G.H. Biodiversity and biogeography of rhizobia associated with common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Shaanxi Province. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 39, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, H.F.; Steadman, J.R.; Hall, R.; Forster, R.L. Compendium of Bean Diseases, 2nd ed.; APS press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2005; pp. Viii+–109. [Google Scholar]

- Celmeli, T.; Sari, H.; Canci, H.; Sari, D.; Adak, A.; Eker, T.; Toker, C. The nutritional content of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) landraces in comparison to modern varieties. Agronomy 2018, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebersax, M.A.; Cichy, K.A.; Gomez, F.E.; Porch, T.G.; Heitholt, J.; Osorno, J.M.; Kamfwa, K.; Snapp, S.S.; Bales, S. Dry beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) as a vital component of sustainable agriculture and food security-A review. Legume Sci. 2023, 5, e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtonga, A.; Maruthi, M.N. Diseases of common bean. In Handbook of Vegetable and Herb Diseases; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Abawi, G.S. Root Rots of Beans in Latin America and Africa: Diagnosis, Research Methodologies, and Management Strategies; CIAT: Cali, Colombia, 1990; p. 114. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.J.; Tu, J.C. Genetic segregation of root rot resistance in dry bean crosses. Bean Improv. Coop. 1994, 37, 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Nderitu, J.H.; Buruchara, R.A.; Ampofo, J.K.O. Relationships between bean stem maggot, bean root rots and soil fertility: Literature review with emphasis on research in eastern and central Africa. Afr. Highl. Initiat. Tech. Rep. Ser. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson-Benavides, B.A.; Dhingra, A. Understanding root rot disease in agricultural crops. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidarian, A. The study and identification of fungi cauding of foot and root rot of pinto beans in Chahar Mahal va Backtiari province. In Proceedings of the 15th Iran Plant Protection Congress; Faculty of Agriculture, Razi University: Kermanshah, Iran, 2004; Volume II, pp. 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Porch, T.G.; Valentin, S.; Jensen, C.; Beaver, J.S. Identification of soil-borne pathogens in a common bean root rot nursery in Isabela Puerto Rico. J. Agric. Univ. Puerto Rico 2014, 98, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Paparu, P.; Acur, A.; Kato, F.; Acam, C.; Nakibuule, J.; Nkuboye, A.; Musoke, S.; Mukankusi, C. Morphological and pathogenic characterization of Sclerotium rolfsii, the causal agent of southern blight disease on common bean in Uganda. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2130–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendi, Y.; Romdhane, S.B.; Mhamdi, R.; Mrabet, M. Diversity and geographic distribution of fungal strains infecting field-grown common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Tunisia. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 153, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lu, X.H.; Wu, B.M.; Li, S.D. First report of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) root rot caused by Plectosphaerella cucumerina in China. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Lu, X.H.; Jing, Y.L.; Li, S.D.; Wu, B.M. First report of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) stem rot caused by Colletotrichum spaethianum in China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, M.C.C.; Stone, A.; Dick, R.P. Organic soil amendments: Impacts on snap bean common root rot (Aphanomyes euteiches) and soil quality. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 2006, 31, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieczarka, D.J.; Abawi, G.S. Effect of interaction between Fusarium, Pythium, and Rhizoctonia on severity of bean root rot. Phytopathology 1978, 68, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cock, A.W.; Lévesque, C.A.; Melero-Vara, J.M.; Serrano, Y.; Guirado, M.L.; Gómez, J. Pythium solare sp. nov., a new pathogen of green beans in Spain. Mycol. Res. 2008, 112, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, J.M.; DW, B.; WA, H. Fusarium Diseases of Beans, Peas and Lentils; The Pennsylvania State University Press: University Park, PA, USA, 1981; pp. 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- Naseri, B. Root rot of common bean in Zanjan, Iran: Major pathogens and yield loss estimates. Austral Plant Pathol. 2008, 37, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.A.; Kelly, J.D. A Greenhouse screening protocol for Fusarium root rot in bean. Hortscience 2000, 35, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Khan, N.; Gong, J.; Hao, X.; Cheng, X.; Chen, X.; Chang, J.; Zhang, H. From an introduced pulse variety to the principal local agricultural industry: A case study of red kidney beans in Kelan, China. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, Q.Q.; He, T.J.; Pan, Y.M.; Chen, T.T. The effect of soaking seeds in oligosaccharides and chain proteins on soybean root rot disease. Zhejiang Agric. Sci. 2021, 62, 2030–2033. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.X. Infestation root rot on common bean and cowpea and their management methods. Sci. Breed. 2013, 6, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.P. Symptom and management methods of common rot root rot. Pestic. Mark. Inf. 2018, 13, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, J.H. Identification of resistance to root rot disease in 18 bean varieties in Dalian area. Chin. J. Melons Veg. 2024, 37, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, F.; Gepts, P.; López, M. Etapas de Desarrollo dela Planta de Frijol común (Phaseolus vulgaris L.); CIAT: Cali, Colombia, 1986; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, M.D.; Munkvold, G.; Ellis, M.; Leandro, L. Distribution and frequency of Fusarium species associated with soybean roots in Iowa. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie, J.F.; Summerell, B.A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; John Wiley & Sons: Ames, Iowa, USA, 2006; p. 388. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.C. The Fungal Identification Manual; Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.Y. Chinese Fungal Chronicles: Alternaria; Science Press: Beijing, China; Chinese Academy of Sciences: Beijing, China, 2003; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Geiser, D.M.; Jiménez-Gasco, M.; Kang, S.; Makalowska, I.; O’Donnell, K. FUSARIUM-ID v. 1.0: A DNA sequence database for identifying Fusarium. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2004, 110, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, R. Die Atiologie de Tuberkulose. Berl. Klin. Wochenschr. 1882, 15, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L.Y. Study on Pathogen Identification and Molecular Detection Technology of Soybean Root Rot. Master’s Thesis, Xingjiang Agricultural University, Urumqi, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoonhoven, A. Standard System for the Evaluation of Bean Germplasm; CIAT: Cali, Colombia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, A.; Menezes, M. Identification and pathogenic characterization of endophytic Fusarium species from cowpea seeds. Mycopathologia 2005, 159, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, B.; Mousavi, S.S. Root rot pathogens in field soil, roots and seeds in relation to common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), disease and seed production. Int. J. Pest. Manag. 2015, 61, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, E.; Fabiola, Y.N.; Vanessa, N.D.; Tobias, E.B.; Marie-Claire, T.; Diane, Y.Y.; Gilbert, G.T.; Louise, N.W.; Fabrice, F.B. The co-occurrence of drought and Fusarium solani f. sp. phaseoli Fs4 infection exacerbates the Fusarium root rot symptoms in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2023, 127, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.M.; Costa, M.M.; Moreira, G.M.; Menezes, A.S.; Lima, C.S.; Pfenning, L.H. Members of the Fusarium solani species complex causing root rot of common bean and cowpea in Brazil. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2025, 50, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltoniemi, K.; Velmala, S.; Lloret, E.; Ollio, I.; Hyvönen, J.; Liski, E.; Brandt, K.K.; Campillo-Cora, C.; Fritze, H.; Iivonen, S. Soil and climatic characteristics and farming system shape fungal communities in European wheat fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 370, 109035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparu, P.; Acur, A.; Kato, F.; Acam, C.; Nakibuule, J.; Musoke, S.; Nkalubo, S.; Mukankusi, C. Prevalence and incidence of four common bean root rots in Uganda. Exp. Agric. 2018, 54, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusuku, G.; Buruchara, R.A.; Gatabazi, M.; Pastor-Corrales, M.A. Occurrence and distribution in Rwanda of soilborne fungi pathogenic to the common bean. Plant Dis. 1997, 81, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austria, R.E.G. Identification and Characterization of Fusarium Species Associated with Root Rot of Chickpea and Bacterial Pathogens of Dry Bean. Master’s Thesis, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND, USA, 5 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ezrari, S.; Radouane, N.; Tahiri, A.; El Housni, Z.; Mokrini, F.; Özer, G.; Lazraq, A.; Belabess, Z.; Amiri, S.; Lahlali, R. Dry root rot disease, an emerging threat to citrus industry worldwide under climate change: A review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 117, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yang, F.; Hu, C.; Yang, X.; Zheng, A.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; He, Y.; Lv, M. Production status and research advancement on root rot disease of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1165658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiskani, A.M.; Samo, Y.; Soomro, M.A.; Leghari, Z.H.; Gishkori, Z.; Bhutto, S.; Majeedano, A. A destructive disease of lentil: Fusarium wilt of lentil. Plant Arch. 2021, 21, 2117–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killebrew, J.; Roy, K.; Abney, T. Fusaria and other fungi on soybean seedlings and roots of older plants and interrelationships among fungi, symptoms, and soil characteristics. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1993, 15, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doohan, F.; Brennan, J.; Cooke, B. Influence of climatic factors on Fusarium species pathogenic to cereals. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2003, 109, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavidas, I.; Ntatsi, G.; Vougeleka, V.; Karkanis, A.; Ntanasi, T.; Saitanis, C.; Agathokleous, E.; Ropokis, A.; Sabatino, L.; Tran, F. Agronomic practices to increase the yield and quality of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): A systematic review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Modi, D.; Picot, A. Soil and phytomicrobiome for plant disease suppression and management under climate change: A review. Plants 2023, 12, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).