Investigating and Quantifying Food Insecurity in Nigeria: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

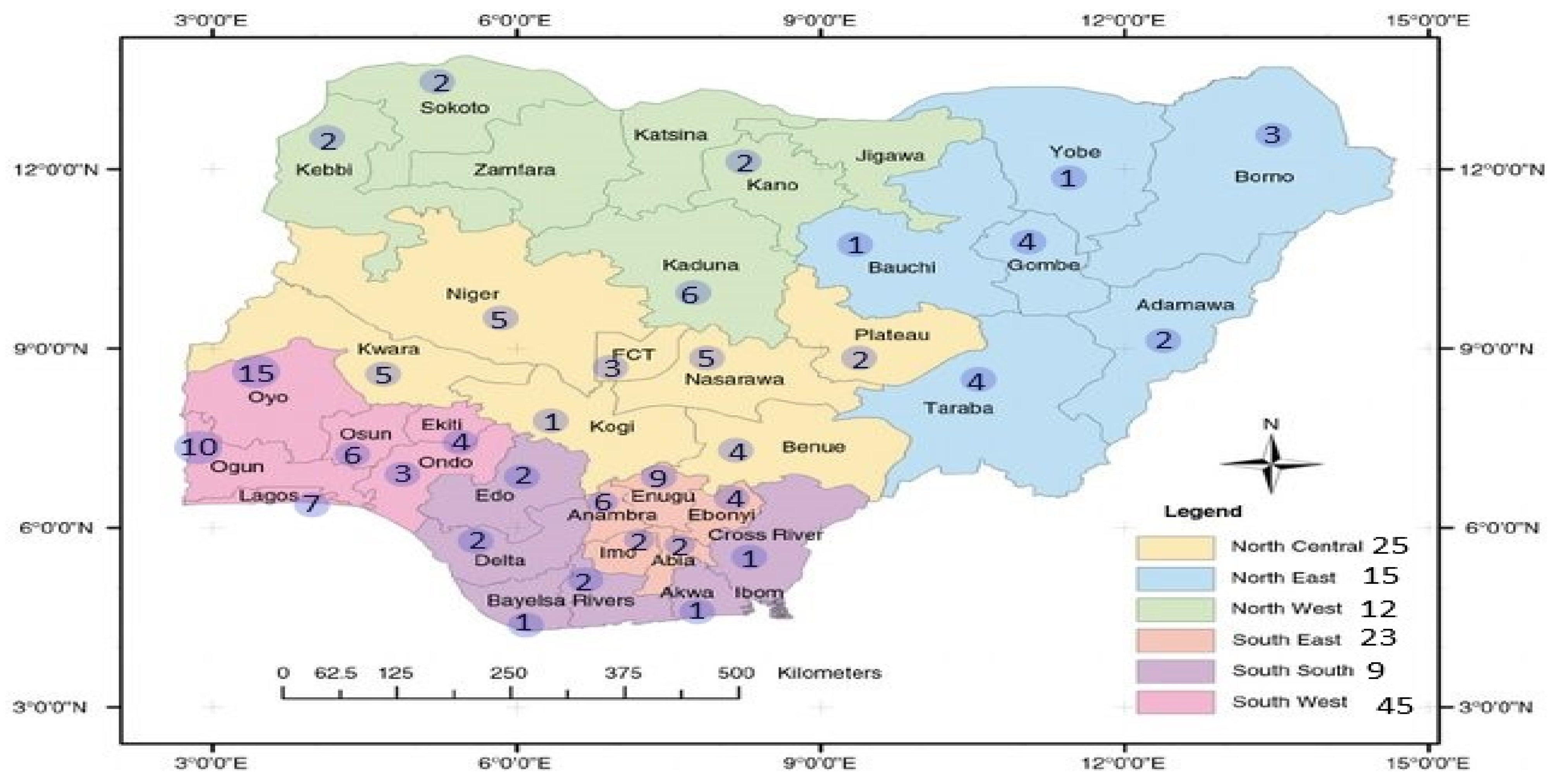

3.1. Common Features of the Reviewed Studies

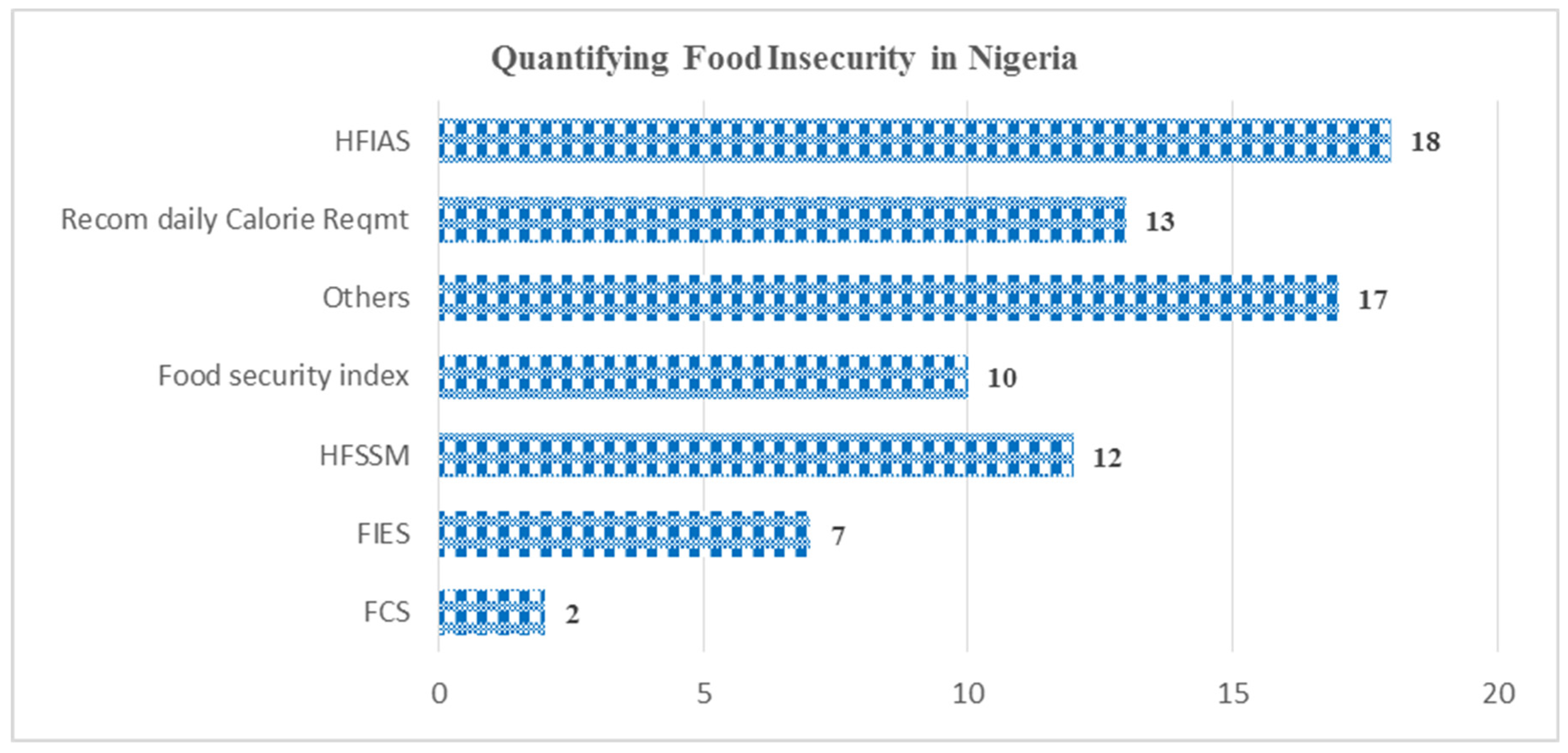

3.2. Quantifying Food Insecurity

3.3. Exploring Food Insecurity in Different Settings

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of This Study

4.2. Areas for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Repurposing Food and Agricultural Policies to Make Healthy Diets More Affordable; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FSIN; Global Network against Food Crises. 2023 Global Report on Food Crises: Joint Analysis for Better Decision; Global Network against Food Crises: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Economist Impact. Global Food Security Index 2022. 2022. Available online: https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/ (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- UNICEF 2023: 25 million Nigerians at High Risk of Food Insecurity in 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/25-million-nigerians-high-risk-food-insecurity-2023 (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Ayinde, I.A.; Sanusi, R.A.; Onabanjo, O.O. Dietary diversity, nutritional status, and agricultural commercialization: Evidence from rural farm households. Dialog. Health 2023, 2, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Grebmer, K.J.; Bernstein, D.; Resnick, M.; Wiemers, L.; Reiner, M.; Bachmeier, A.; Hanano, O.; Towey, R.; Ni Cheilleachair, C. 2022 Global Hunger Index: Food Systems 7. Transformation and Local Governance; Welthungerhilfe: Bonn, Germany; Concern Worldwide: Dublin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Rome declaration on the world food security and world food summit plan of action. In Proceedings of the World Food Summit 1996, Rome, Italy, 13–17 November 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Piperata, B.A.; Scaggs, S.A.; Dufour, D.L.; Adams, I.K. Measuring food insecurity: An introduction to tools for human biologists and ecologists. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2023, 35, e23821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, R.; Schoeneberger, H.; Pfeifer, H.; Preuss, H.-J. The four dimensions of food and nutrition security: Definitions and concepts. SCN News 2000, 20, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- De Haen, H.; Klasen, S.; Qaim, M. What do we really know? Metrics for food insecurity and under nutrition. Food Policy 2011, 36, 760–769. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.D.; Ngure, F.M.; Pelto, G.; Young, S.L. What are we assessing when we measure food security? A Compendium and review of current metrics. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Headey, D.; Ecker, O. “Improving the Measurement of Food Security” (No. 01225). IFPRI Discussion Paper 01225. 2012. Available online: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/127261 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Ike, C.U.; Jacobs, P.; Kelly, C. Towards comprehensive food security measures: Comparing key indicators. Afr. Insight 2015, 44, 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ayinde, I.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Akinbode, S.O.; Otekunrin, O.A. Food Security in Nigeria: Impetus for Growth and Development. J. Agric. Econ. Rural Dev. 2020, 6, 808–820. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, F.H.; Haines, B.C.; Dunn, M. Measuring and understanding food insecurity in Australia: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, P.; Coates, J.; Frongillo, E.A.; Rogers, B.L.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Measuring household food insecurity: Why it’s so important and yet so difficult to do. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 1404S–1408S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Momoh, S.; Ayinde, I.A. How far has Africa gone in achieving the Zero Hunger Target? Evidence from Nigeria. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Sawicka, B.; Ayinde, I.A. Three decades of fighting against hunger in Africa: Progress, challenges and opportunities. World Nutr. 2020, 11, 86–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otekunrin, O.A. Investigating food insecurity, health and environment-related factors, and agricultural commercialization in Southwestern Nigeria: Evidence from smallholder farming households. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 29, 51469–51488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global FoodBanking Network. The FoodBank Hunger Report: Driving Advocacy for Zero Hunger in Australia. 2023. Available online: https://www.foodbanking.org/blogs/the-foodbank-hunger-report-driving-advocacy-for-zero-hunger-in.australia/#:~:text=The%20state%20of%20Australia’s%20food,over%20the%20previous%20twelve%20months (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2019. Economic Research Report No. (ERR-275); U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Volume 47.

- Chilton, M.; Chyatte, M.; Breaux, J. The negative effects of poverty and food insecurity on child development. Indian J. Med. Res. 2017, 126, 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Ivers, L.C.; Cullen, K.A. Food insecurity: Special considerations for women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1740S–1744S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odoms-Young, A.M. Examining the impact of structural racism on food insecurity: Implications for addressing racial/ethnic disparities. Fam. Community Health 2018, 41, S3–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, J.K.; Shokoohi, M.; Salway, T.; Ross, L.E. Sexual orientation–based disparities in food security among adults in the United States: Results from the 2003–2016 NHANES. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 2006–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daponte, B.O.; Lewis, G.H.; Sanders, S.; Taylor, L. Food pantry use among low-income households in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. J. Nutr. Educ. 1998, 30, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeronim, C.; Panagiotis, K.; Marco, K.; Mark, S. A Model of Vulnerability to Food Insecurity; ESA Working Paper 2010, No. 10-03. Agricultural Development Economics Division. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/012/al318e/al318e.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Ramsey, R.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G.; Gallegos, D. Food insecurity among adults residing in disadvantaged urban areas: Potential health and dietary consequences. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obayelu, O.A.; Akpan, E.I. Food insecurity transitions among rural households in Nigeria. Estud. De Econ. Apl. 2021, 39, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Radimer, K.L.; Olson, C.M.; Greene, J.C.; Campbell, C.C.; Habicht, J.P. Understanding hunger and developing indicators to assess it in women and children. J. Nutr. Edu. 1992, 24, 36S–44S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Cook, J.T. Household Food Security in the United States in 1995: Technical Report of the Food Security Measurement Project; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security; Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, Egypt, 2000.

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v. 3); FHI 360/FANTA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Methods for Estimating Comparable Rates of Food Insecurity Experienced by Adults throughout the World; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cafiero, C.; Viviani, S.; Nord, M. Food security measurement in a global context: The food insecurity experience scale. Measurement 2018, 116, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.D.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Who are the world’s food insecure? New evidence from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s food insecurity experience scale. World Dev. 2017, 93, 402–412. [Google Scholar]

- Frongillo, E.A.; Nguyen, H.T.; Smith, M.D.; Coleman-Jensen, A. Food Insecurity Is Associated with Subjective Well-Being among Individuals from 138 Countries in the 2014. Gallup World Poll. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 680–687. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.D. Food insecurity and mental health status: A global analysis of 149 countries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbule, O.O.; Okekhian, K.L.; Omidian, A. Assessing the Household Food Insecurity Status and Coping Strategies in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. J. Nutr. Food Secur. 2020, 4, 236–242. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, F.O.; Eyinla, T.E.; Ariyo, O.; Leshi, O.O.; Brai, B.I.C.; Afolabi, W.A.O. Food Access and Experience of Food Insecurity in Nigerian Households during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Food Nutr. Sci. 2021, 12, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balana, B.; Ogunniyi, A.; Oyeyemi, M.; Fasoranti, A.; Edeh, H.; Andam, K. COVID-19, food insecurity and dietary diversity of households: Survey evidence from Nigeria. Food Secur. 2023, 15, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaza, P.; Abdoulaye, T.; Kwaghe, P.; Tegbaru, A. Changes in Household Food Security and Poverty Status in PROSAB Areas of Southern Borno State, Nigeria. Promoting Sustainable Agriculture in Borno State (PROSAB); International Institute of Tropical Agriculture: Ibadan, Nigeria, 2009; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Fawehinmi, O.A.; Adeniyi, O.R. Gender dimensions of food security status of households in Oyo State, Nigeria. Glob. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2014, 14, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Obayelu, A.O.; Orosile, O.R. Rural livelihood and food poverty in Ekiti State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Environ. Int. Dev. 2015, 109, 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, S.; Kemaw, B. Analysis of households’ food insecurity and its coping mechanisms in Western Ethiopia. Agric. Food Econ. 2019, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunniyi, A.I.; Omotoso, S.O.; Salman, K.K.; Omotayo, A.O.; Olagunju, K.O.; Aremu, A.O. Socio-economic Divers of Food Security among Rural Households in Nigeria: Evidence from Smallholder Maize Farmers. Soc. Ind. Res. 2021, 155, 583–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, R.O.; Omotosho, O.A.; Sholotan, O.S. Socioeconomic characteristics and food security status of farming households in Kwara State, North-Central Nigeria. Pak. J. Nutr. 2007, 6, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Obayelu, O.A.; Onasanya, O.A. Maize Biodiversity and Food Security Status of Rural Households in the Derived Guinea Savannah of Oyo Sate, Nigeria. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2016, 81, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Fawole, W.O.; Ozkan, B.; Ayanrinde, F.A. Measuring food security status among households in Osun State, Nigeria. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biam, C.K.; Tavershima, T. Food Security Status of Rural Households in Benue State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Food Nutr. Dev. 2020, 20, 15677–15694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Food Programme. Food Consumption Analysis: Calculation and Use of the Food Consumption Score in Food Consumption and Food Security Analysis. Technical Guidance Sheet; World Food Programme: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Assoumou, B.O.M.T.; Coughenour, C.; Godbole, A.; McDonough, I. Senior food insecurity in the USA: A systematic literature review. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 26, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misselhorn, A.; Hendriks, S.L. A systematic review of sub-national food insecurity research in South Africa: Missed opportunities for policy insights. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, M.O.; Yawson, D.O.; Armah, F.A.; Abano, E.A.; Quansah, R. Systematic review of the effects of agricultural interventions on food security in Northern Ghana. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militao, E.M.A.; Salvador, E.M.; Uthman, O.A.; Vinberg, S.; Macassa, G. Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes Other than Malnutrition in Southern Africa: A Descriptive Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassara, G.; Chen, J. Household Food Insecurity, Dietary Diversity, and Stunting in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanusi, R.A.; Badejo, C.A.; Yusuf, B.O. Measuring Household Food Insecurity in Selected Local Government Areas of Lagos and Ibadan, Nigeria. Pak. J. Nutr. 2006, 5, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Falola, O.A. Assessing Farmers’ Household Food Insecurity Access Prevalence and Food Security Status in Southwest Nigeria. Ethiopian Renaiss. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 7, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ene-Obong, H.N.; Onuoha, N.O.; Eme, P.E. Gender roles, family relationships, and household food and nutrition security in Ohafia matrilineal society in Nigeria. Matern. Child Nurs. 2017, 13, e12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamiwuye, O.; Akintunde, O.; Jimoh, L.; Olanrewaju, K. Perceived changes in food security, finances and revenue of rural and urban households during COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Agrekon 2022, 61, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folayan, M.O.; Ibigbami, O.; Brown, B.; El Tantawi, M.; Uzochukwu, B.; Ezechi, O.C.; Aly, N.M.; Abeldaño, G.F.; Ara, E.; Ayanore, M.A.; et al. Differences in COVID-19 Preventive Behavior and Food Insecurity by HIV Status in Nigeria. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alene, A.D.; Manyong, V.M. Endogenous technology adoption and household food security: The case of improved cowpea varieties in northern Nigeria. Quart. J. Int. Agric. 2006, 3, 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- Okezie, C.A.; Nwosu, A.C.; Baharuddin, A.H. Rising Food Insecurity: Dimensions in Farm Households. Am. J. Agric. Bio Sci. 2011, 6, 403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Akindola, R.B. Household food insecurity and nutrition status: Implications for child’s survival in South-Western Nigeria. Asian J. Agric. Rural Dev. 2020, 10, 120–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejemeyovwi, J.O.; Osabohien, R.; Adeleye, B.N. Household ICT Utilization and Food Security Nexus in Nigeria. Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 5551363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omonona, B.T.; Agoi, G.A. An analysis of food security situation among Nigerian urban households: Evidence from Lagos State, Nigeria. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2007, 8, 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Fakayode, S.B.; Rahji, M.A.Y.; Oni, O.A.; Adeyemi, M.O. An Assessment of Food Security Situations of Farm Households in Nigeria. Soc. Sci. 2009, 4, 2–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, H.; Bello, M.; Ibrahim, H. Food Security and Resource Allocation among Farming Households in North Central Nigeria. Pak. J. Nutr. 2009, 8, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ibrahim, H.; Uba-Eze, N.R.; Oyewole, S.O.; Onuk, E.G. Food Security among Urban Households: A Case Study of Gwagwalada Area Council of the Federal Capital Territory Abuja, Nigeria. Pak. J. Nutr. 2009, 8, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ajao, K.O.; Ojofeitimi, E.O.; Adebayo, A.A.; Fatusi, A.O.; Afolabi, O.T. Influence of family size, household food security status, and child care services on the nutritional status of under-five children in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2010, 14, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Babatunde, R.O.; Qaim, M. Impact of off-farm income on food security and nutrition in Nigeria. Food Policy 2010, 35, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekini, O.T. Women’s Participation in Development Programs and Food Security Status. J. Agric. Food Inf. 2010, 11, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omojimite, B.U. Analysis of Food Security situation in Warri, Nigeria. J. Soc. Dev. Sci. 2011, 2, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuemu, V.O.; Otasowie, E.M.; Onyiriuka, U. Prevalence of food insecurity in Egor Local Government Area of Edo State, Nigeria. Ann. Afr. Med. 2012, 11, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerele, D.; Momoh, S.; Aromolaran, A.B.; Oguntona, C.R.B.; Shittu, A.M. Food insecurity and coping strategies in South-West Nigeria. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayiwola, I. Coping strategy for food security among elderly in Ogun state, Nigeria. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2013, 16, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Odusina, O.A. Assessment of Households’ food access and food insecurity in urban Nigeria: A case study of Lagos Metropolis. Glob. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2014, 15, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, F.M.; Ojo, M.O.; Osikabor, B.; Akinosho, H.O.; Ibrahim, A.B.; Olatunji, B.T.; Ogunwale, O.G.; Akanni, O.F. Gender Role Attitude and Food Insecurity among Women in Ibadan, Nigeria. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obisesan, O.A. Causal Effects of off-farm activity and technology adoption on food security in Nigeria. Agris Econ. Inform. 2015, 7, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzeagwu, O.; Aleke, U. Household Nutrition and Food Security in Obukpa Rural Community of Enugu State, Nigeria. Malays. J. Nutr. 2016, 22, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Olaniyi, O.A.; Ismaila, K.O. Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) usage and household food security status maize crop farmers in Ondo State, Nigeria: Implication for Sustainable Development. Lib. Phil. Pract. 2016, 1446, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ajaero, C.K. A gender perspective on the impact of flood on the food security of households in rural communities of Anambra state, Nigeria. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehebhamen, O.G.; Obayelu, A.E.; Vaughan, I.O.; Afolabi, W.A.O. Rural Households’ food security status and coping strategies in Edo State, Nigeria. Int. Food Res. J. 2017, 24, 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sholeye, O.O.; Animasahun, V.J.; Salako, A.A.; Oyewole, B.K. Household food insecurity among people living with HIV in Sagamu, Nigeria: A preliminary study. Nutr. Health 2017, 23, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoo, N.S. Food insecurity and family structure in Nigeria. SSM Pop. Health 2018, 4, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, A.; Oyegoke, O. Correlates of food insecurity status of urban households in Ibadan metropolis, Oyo State, Nigeria. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 2248–2254. [Google Scholar]

- Fawole, W.O.; Ozkan, B. Food insecurity risks perceptions and management strategies among households: Implications for zero hunger target in Nigeria. New Medit 2018, 2, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.K.; Mustafa, A.S. Food security and productivity among urban farmers in Kaduna State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. 2018, 22, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danladi, H.; Ojo, C.O. Analysis of food access status among farming households in Southern part of Gombe State, Nigeria. Green J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 8, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris-Adeniyi, K.M.; Akinbile, L.A.; Busari, A.O.; Adebooye, O.C. Factors influencing household food security among MicroVeg project beneficiaries in Nigeria. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1238, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.A.; Osadare, J.O.; Imem, V.A. Hunger iin the midst of plenty: A survey of household food security among urban families in Lagos State, Nigeria. J. Public Health Afr. 2019, 10, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salau, S.A.; Aliu, S.R.; Nofiu, N.B. The effect of sustainable land management technologies on farming household food security in Kwara State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 64, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholeye, O.A.; Animasahun, V.J.; Salako, A.A. A world free of hunger: An assessment of food security and dietary diversity among adult primary care clients in rural southwest Nigeria. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 49, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukegbu, P.; Nwofia, B.; Ndudiri, U.; Nwakwe, N.; Uwaegbute, A. Food insecurity and associated factors among University students. Food Nutr. Bull. 2019, 40, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesoye, O.P.; Adepoju, A.O. Food insecurity status of the working poor households in Southwest Nigeria. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2020, 47, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akukwe, T.I.; Oluoko-Odingo, A.A.; Krhoda, G.O. Do floods affect food security? A before-and-after comparative study of flood-affected households’ food security status in South-Eastern Nigeria. Bull. Geog. Soc. Ser. 2020, 47, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anugwa, I.Q.; Agwu, A.E.; Suvedi, M.; Babu, S. Gender-Specific Livelihood Strategies for Coping with Climate Change-Induced Food Insecurity in Southeast Nigeria. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 1065–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaka, I.D.; Akadiri, S.S.; Uma, K.E. Gender of the family head and food insecurity in urban and rural Nigeria. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2020, 11, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarinde, L.O.; Abass, A.B.; Abdoulaye, T.; Adepoju, A.A.; Adio, M.O.; Fanifosi, E.G.; Awoyale, W. The influence of Social Networking on Food Security Status of Cassava Farming Households in Nigeria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyawole, F.; Dipeolu, A.; Shittu, A.; Obayelu, A.; Fabunmi, T. Adoption of agricultural practices with climate smart agriculture potentials and food security among farm households in northern Nigeria. Open Agric. 2020, 5, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozioko, R.I.; Nwigwe, B.C.; Asadu, A.N.; Nwafor, M.I.; Nnadi, O.I.; Onyia, C.C.; Enwelu, I.A.; Oluwasegun, F.O. Food Security Situations among Female Headed Households in Enugu East Senatorial Zone of Enugu State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. 2020, 24, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapu, R.S.; Ismail, S.; Ahmad, N.; Lim, P.Y.; Njodi, I.A. Food Security and Hygiene Practice among Adolescent Girls in Maiduguri Metropolitan Council, Borno State, Nigeria. Foods 2020, 9, 1265. [Google Scholar]

- Sennuga, O.S.; Baines, R.N.; Conway, J.S.; Naylor, R.K. Effect of Smallholders Socio-Economic Characteristics on Farming Households’ Food Security in Northern Nigeria. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Amolegbe, K.B.; Upton, J.; Bageant, E.; Bloom, S. Food price volatility and household food security. Evidence from Nigeria. Food Policy 2021, 102, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeama, N.N.; Ibeh, C.C.; Adinma, E.D.; Epundu, U.U.; Chiejine, G.I. Burden of food insecurity, sociodemographic characteristics and coping practices of households in Anambra State, South-eastern Nigeria. J. Hung. Environ. Nutr. 2021, 16, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibukun, C.O.; Adebayo, A.A. Household food security and the COVID-19 pandemic. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2021, 33 (Suppl. 1), S75–S87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassy, W.C.; Ndu, A.C.; Okeke, C.C.; Aniwada, E.C. Food Security and Factors Affecting Household Food Security in Enugu State, Nigeria. J. Health Underserved 2021, 32, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehinde, M.O.; Shittu, A.M.; Adeyonu, A.G.; Ogunnaike, M.G. Women empowerment, Land Tenure and Property Rights, and household food security among smallholders in Nigeria. Agric. Food Secur. 2021, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehinde, M.O.; Shittu, A.M.; Adewuyi, S.A.; Osunsina, I.O.O.; Adeyonu, A.G. Land Tenure and Property rights, and household food security among rice farmers in northern Nigeria. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obayelu, O.A.; Akpan, E.I.; Ojo, A.O. Pevalence and correlates of food insecurity in rural Nigeria: A panel analysis. J. Agric. Food Syst. 2021, 23, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Sawicka; Pszczolkowski, P. Assessing food insecurity and its drivers among smallholder farming households in rural Oyo State, Nigeria. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, S.P.; Sanusi, R.A.; Eyinla, T.E.; Samuel, F.O. Household food insecurity and Nutrient Adequacy of under-five children in selected urban areas of Ibadan, Southwestern, Nigeria. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2021, 24, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Folayan, M.O.; Ibigbami, O.; El Tantawi, M.; Brown, B.; Aly, N.M.; Ezechi, O.; Abeldaño, G.F.; Ara, E.; Ayanore, M.A.; Ellakany, P.; et al. Factors Associated with Financial Security, Food Security and Quality of Daily Lives of Residents in Nigeria during the FirstWave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebisi, L.O.; Adebisi, O.A.; Odum, E.E. Effect of climate smart agricultural practices on food security among farming households in Kwara State, North-Central Nigeria. Pesq. Agropec. Trop. 2022, 52, e70538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeomi, A.A.; Fatusi, A.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K. Food Security, Dietary Diversity, Dietary Patterns and the Double Burden of Malnutrition among School-Aged Children and Adolescents in Two Nigerian States. Nutrients 2022, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye, P.A.; Afolahanmi, T.O.; Ofili, A.N.; Chirdan, O.O.; Agbo, H.A.; Adeoye, L.T.; Su, T.T. Socio-demographic predictors of food security among rural households in Langai district in Plateau-Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 43, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashagidigbi, W.M.; Orilua, O.O.; Olagunju, K.A.; Omotayo, A.O. Gender, Empowerment and Food Security Status of Households in Nigeria. Agriculture 2022, 12, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne, E.; Folayan, M.O.; Arije, O.; Enemo, A.; Sunday, A.; Muhammad, A.; Nyako, H.Y.; Abdullah, R.M.; Okiwu, H.; Undelikwo, V.A.; et al. Effects of COVID-19 on food insecurity, financial vvulnerability and housing insecurity among women and girls living with or at risk of HIV in Nigeria. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2022, 21, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munonye, J.; Osuji, E.; Olaolu, M.; Okoisu, A.; Obi, J.; Eze, G.; Ibrahim-Olesin, S.; Njoku, L.; Amadi, M.; Izuogu, C.; et al. Perceived Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Security in Southeast Nigeria. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 936157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnaji, A.; Ratna, N.N.; Renwick, A. Gendered access to land and household food insecurity: Evidence from Nigeria. Agric. Res. Econ. Rev. 2022, 51, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiemela, S.N.; Chiemela, C.J.; Apeh, C.C.; Ileka, C.M. Households Food and Nutrition Security in Enugu State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Ext. 2022, 26, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Omotayo, A.O.; Omotoso, A.; Daud, S.A.; Omoayo, P.O.; Adeniyi, B.A. Rising Food Prices and Food Insecurity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Policy Implications from SouthWest Nigeria. Agriculture 2022, 12, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyenekwe, C.S.; Okpara, U.T.; Opata, P.I.; Egyir, I.S.; Sarpong, D.B. The Triple Challenge: Food Security and Vulnerabilities of Fishing and Farming Households in Situations Characterized by Increasing Conflict, Climate Shock, and Environmental Degradation. Land 2022, 11, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salau, S.A.; Olalere, I.; Affolabi, D.G. Analysis of food security among garri processors in Oyo State, Nigeria. Trop. Agric. 2022, 99, 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Omachi, B.A.; Van Onselen, A.; Kolanisi, U. The Household Food Security and Feeding Pattern of Preschool Children in North-Central Nigeria. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, M.D.; Adewumi, M.O. Food security among cashew farming households in Kogi state, Nigeria. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 3953–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwala, D.G.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Adebowale, O.O.; Fasina, M.M.; Odetokun, I.A.; Fasina, F.O. COVID-19 Pandemic Impacted Food Security and Caused Psychosocial Stress in Selected States of Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orjiakor, E.C.; Adediran, A.; Ugwu, J.O.; Nwachukwu, W. Household living conditions and food insecurity in Nigeria: A longitudinal study during COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyeniran, I.O.; Olajide, O.A. Assessing food security status of rural households in North Eastern Nigeria: A Comparison of Methodologies. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2023, 23, 22513–22533. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.; Turk, R. Food Insecurity in Nigeria: Food Supply Matters; IMF Selected Issues Paper: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Melga-Quinonez, H. Testing Food-Security Scales for Low-Cost Poverty Assessment. Research Report; Ohio State University, For Freedom from Hunger: Davis, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v.2); FHI 360/FANTA: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. Available online: http://www.fantaproject.org/downloads/pdfs/HDDS_v2_Sep06.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2023).

- Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET). Nigeria—Food Security Outlook 2023. Available online: https://fews.net/fr/west-africa/nigeria/food-security-outlook/march-2023 (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Ordinioha, B.; Sawyer, W. Food insecurity, malnutrition and crude oil spillage in a rural community in Bayelsa State, South-South Nigeria. Niger. J. Med. 2008, 17, 3044–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKechnie, R.; Turrell, G.; Giskes, K.; Gallegos, D. Single-item measure of food insecurity used in the National Health Survey may underestimate prevalence in Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2018, 42, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Fasina, F.O.; Omotayo, A.O.; Akram, M. Assessing the Zero Hunger Readiness in Africa in the Face of COVID-19 Pandemic. Caraka Tani. J. Sustain. Agric. 2020, 35, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, M.; Rikard-Bell, G.; Mohsin, M.; Williams, M. Food insecurity in three socially disadvantaged localities in Sydney, Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2006, 17, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Serebryanikova, I.; Donaldson, K.; Leveritt, M. Student food insecurity: The skeleton in the university closet. Nutr. Dietet. 2011, 68, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, B.; Yamazaki, R.; Franke, E.; Amanatidis, S.; Ravulo, J.; Steinbeck, K.; Ritchie, J.; Torvaldsen, S. Sustaining dignity? Food insecurity in homeless young people in urban Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2014, 25, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Location | Population Group | Study Aim | Findings | Primary Method | Method for Assessing FI | FI Prevalence | Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [57] | Oyo and Lagos states | School-going children in Lagos and Ibadan | To delineate the food security status of households headed by teachers in public and private schools | The prevalence of food security (26%) in teachers’ households in Lagos and Ibadan was low, while the food security level of households in Lagos was better than those in Ibadan | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA 18 Question Households Food Security Module (HFSSM) | 76.3% (Ibadan); 72% (Lagos) | 482 households |

| [62] | Borno state | Rural households | The study examined and analyzed the food security status of rural households in Borno state | The results indicated that a FI line of NGN 23,700.12 or USD 176.87 per adult equivalent per year was obtained among households in the state | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily energy level approach (2250 Kcal) | 58.0% | 1200 households |

| [47] | Kwara state | 12 villages of rural farm households | To investigate the socioeconomic attributes and correlates of FI of rural farming households | About 36% of the farm households were food secure while 64% were food insecure. Thirty-eight percent of the food-insecure households did not meet the recommended calorie intake | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2260 Kcal) | 38.0% | 94 rural farm households |

| [66] | Lagos state | Professionals, artisans, traders, and unemployed | To analyze the food security situation among urban households in Kosofe LGA of Lagos state | The study indicated that FI was higher in FHHs than in MHHs. The study also reported that FI reduces when the education level goes up | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food security Index: Per capita food expenditure (food security line = N7, 967.19) | Professional (55%); Artisan (19%); traders (22%); unemployed (4%). | 165 urban households |

| [67] | Ekiti state | 16 villages of farming households in two Agricultural Development Project zones | To investigate food security situations among rural farm households in Ekiti state | The study reported 12.2% food secure and 87.8% food insecure farm households in the study area. Also, cassava, yam, and their products were found to contribute greatly to the food security status of the farming households | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA 16-Question HFSSM approach | 87.8% | 160 farm households |

| [68] | Nassarawa state | 15 farming communities in 3 LGAs | To determine food security status and the optimal farm plan of farming households in 3 LGAs of Nassarawa state | The study revealed 58.9% FI among farming households. Also, maize, yam, and cassava were identified as significant food security crops among farm households | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily per capita calorie intake of 2470 Kcal | 58.9% | 180 farm households |

| [69] | Abuja | Urban households in three wards (Quarters, Central, and Kuttunku) | To assess the food security status of urban households in FCT | The study reported that 70% of urban households were food secure, while 30% were food insecure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food security scale and frequency counts (developed by Freedom from Hunger (FFH)) | 30.0% | 120 urban households. |

| [70] | Osun state | Ife Central LGA (rural and urban settlements) | To assess the influence of family size, household food security status, and childcare practices on the nutritional status of under-5 children in Ile-Ife, Nigeria | Under-5 children in food-insecure households were 5 times more likely to be wasted than in food-secure households | Survey (Cross-sectional) | 18-item HFSSM approach | 65.0% | 423 (Under-five children/mothers) |

| [71] | Kwara state | 40 villages in 8 LGAs of Kwara state | To examine the effect of off-farm income on household calorie and micronutrient supply, dietary quality, and child anthropometry | The study reported that off-farm income had a positive net effect on food security and nutrition. | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2500 Kcal) | N/A | 220 households |

| [72] | Oyo state | One LGA (Ogbomoso South) of Oyo state. Participants and non-participants in development programmes | To assess rural women’s participation in development programmes and their food security status | The study reported that 93% of the respondents were aware of the development programmes while 23.6%, 60.9%, and 15.5% indicated high, average, and low levels of participation, respectively | Survey, focus group discussion (FGD) | Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) Approach | 52.7% | 110 respondents |

| [73] | Delta state | 8 communities in Warri, Delta state | To investigate food insecurity incidence in an “oil city’’ of Warri, Nigeria | The study revealed that food insecurity incidence decreases as the level of income increases. Also, household size had a direct relationship with food insecurity incidence | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Insecurity Index (per capita food expenditure) Approach (food security line = N10, 704.27) | Oil workers (42%); traders (23%); civil servants (23%); unemployed (6%). | 260 households |

| [74] | Edo state | Egor LGA | To assess food insecurity situations in Egor LGA of Edo state | Food insecurity was higher among female-headed households (FHHs) and those with larger household sizes | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS approach | 61.8% | 416 households |

| [75] | Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti state | 5 political wards in 10 streets of Ekiti | To investigate food insecurity and coping strategies in Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti state, Nigeria | The overall food insecurity status of the households was 58.8%, while the depth of food insecurity (expressed as the average percent increase in calories required to meet the recommended daily requirement) was 19.5% | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2550 Kcal) | 58.8% | 80 households, 321 members |

| [76] | Ogun state | 3 senatorial districts in Ogun state | To assess coping strategies for food security among the elderly in Ogun state, Nigeria | The study reported that 88% of the participants were food secured. The coping strategies reported were the use of cooperatives, banks, and daily money savings | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Assessing food habit | 12% | 310 participants |

| [77] | Lagos state | 3 LGAs based on income groups: Ikoyi (high income), Surulere (middle income), and Agege (low income) | To assess the prevalence of food insecurity and the level of household food access in the Lagos metropolis | The study revealed that households in the Lagos metropolis had adequate food access with an HFIAS score of 6.45 ± 0.41 (harvest period) and that it worsened significantly to mean food access of 12.44 ± 0.45 during the hunger period | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS approach | Low-income group (50.8%); Middle income (51.7%); High income (27.5%) | 180 households |

| [78] | Oyo state | 2 LGAs in Ibadan; Ibadan North West and Ibadan South West | To examine gender role attitudes as they affect food insecurity in the Ibadan Metropolis | The study reported that the pattern of gender role attitude is quasi-traditional, while an egalitarian disposition to gender roles is yet to be firmly rooted, and food insecurity is still a plague among women | Survey (Cross-sectional) | The 4-item women’s hunger sub-scale | 87.8% | 617 households |

| [79] | Ondo and Ogun states | 8 LGAs comprising 24 communities in the two states | To examine off-farm activity participation, technology adoption, and impact on the food security status of Nigerian farming households | The study reported that the impact of improved technology adoption on the food insecurity level of adopters with off-farm activity was higher than their counterparts without participation | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Insecurity Index (per capita food expenditure) Approach (food security line = NGN 20,132.22) | 50.7% (technology adopters); and 56.3% (technology non-adopters). | 482 households |

| [49] | Osun state | Three agricultural zones, namely: Osogbo, Iwo, and Ife/Ijesha | To investigate the food security status of households in Osun state of Nigeria | The study revealed that most of the households fell below the recommended daily per capita calorie intake, with a food insecurity gap of 0.0038 | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2710 Kcal) | 54% | 150 households |

| [80] | Enugu state | 3 rural communities in the Nsukka LGA | To investigate household nutrition and food security in a rural community of the Nsukka Local Government Area (LGA) of Enugu state, Nigeria | About 43% were subsistence farmers, and 27% depended on borrowing food items to cope with nutritional and food security challenges | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA FSSM Approach | 93.5% | 263 households with 87 under-five children |

| [48] | Oyo state | Rural maize farm households in Oyo and Shaki | To examine the effects of maize biodiversity on the household food security status of rural maize farm households in the Southern Guinea Savannah of Oyo state, Nigeria | The study reported that food security headcount increases with maize richness, cultivar evenness, and relative abundance | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2260 Kcal) | 23.5% | 200 households |

| [81] | Ondo state | Maize farming households in 44 villages | To assess ICT usage and household food security status of maize crop farmers in Ondo state, Nigeria. | The study revealed that cell phones, radio, and television were the most available ICT tools for accessing information on food security dimensions | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 52.4% | 212 rural farmers |

| [82] | Anambra state | 4 rural LGAs, namely: Anyamelum, Ogbaru, Anambra West, and Anambra East LGAs | To examine gender perspectives of the implications of the severe 2012 flood on household food security in rural Anambra state | The study reported a higher level of food insecurity in both male-headed and female-headed households after the 2012 flood incident in the study area | Survey (Cross-sectional); FGD | Food Security Index Approach (3-item question) | Before the flood: FHH, 11%; male-headed households (MHHs), 16%. After flood: FHH, 78%; MHH, 66%. | 240 households (120 [MHHs] and 120 [FHHs]) |

| [83] | Edo state | 3 LGAs in 15 rural communities | To examine rural households’ food security status and coping strategies in Edo state | The study revealed that less than half (47.3%) of the rural households were classified as food secure | Survey (Cross-sectional); FGD | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2100 Kcal) | 52.7% | 150 rural households |

| [59] | Abia state | Three autonomous communities, namely: Akanu Ukwu, Okamu, and Isiama in Ohafia | To examine gender roles, family relationships, food security, and the nutritional status of households in Ohafia | The study reported that 65.5% of the households were said to experience little or no hunger, whereas 33.8% experienced moderate hunger, and 0.7% had severe hunger | Survey (Cross-sectional); FGD | Household Hunger Scale (HHS); dietary diversity score | 66.0% | 287 households |

| [84] | Ogun state | People living with HIV in Sagamu | To determine the prevalence of household food insecurity and its associated factors among people living with HIV in Sagamu, Ogun state | The study reported that food insecurity was associated with major predictors, such as educational status, occupation, type of housing, delaying drugs to prevent hunger, and exchanging sex for food | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 71.7% | 244 adult participants |

| [85] | Nigeria | Polygynous family structures | To explore the relationship between polygyny (man marrying more than one wife) and food security in Nigeria | The study revealed that at the household level, polygynous households are found to have better food security outcomes than monogamous households | Survey (secondary General Household Survey panel data) | Food consumption score; reduced coping strategies index (RCSI) | N/A | 5000 households |

| [86] | Oyo state | Households in the Ibadan Metropolis | To determine the correlates of food insecurity of households in Ibadan Metropolis | The study reported that the estimated food insecurity line was NGN 1948.82 | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Insecurity Index (per capita food expenditure) Approach (food security line = NGN 1948.82) | 29.3% | 150 households |

| [87] | Oyo and Ogun state | 5 LGAs in Oyo and 4 LGAs in Ogun | To determine food insecurity risk perception and management strategies among households in Ogun and Oyo states | The findings indicated that the majority of the households (87.6%) manifested various forms of food insecurity risks | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Assessing food insecurity risks | 87.6% | 161 households |

| [88] | Kaduna state | Urban farmers in Kaduna North, Kaduna South, Jema’a, Zaria, and Sabon Gari LGAs | To investigate food security and productivity among urban farmers in Kaduna state | The results revealed that 54.5% of the households were food insecure, while the average daily per capita calorie intake for food-secure households was 5516.28 kcal | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2250 kcal) | 54.5% | 213 urban households |

| [89] | Gombe state | Farming households in 8 villages in Southern Gombe | To determine food access status among farming households in the southern part of Gombe state | The findings showed that about 27 percent of the farming households were food secure, 35 percent were mildly food insecure, 18.3 percent were moderately food insecure, and 20 percent were severely food insecure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 73.5% | 120 households |

| [90] | Four undisclosed states | MicroVeg projects beneficiaries | To examine factors influencing household food security amongst MicroVeg project beneficiaries in Nigeria | The findings revealed that household composition (more specifically, the ratio of male members in the active working age bracket) was found to influence food security among households | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 45.8% | 120 households |

| [91] | Lagos state | Urban households in Shomolu LGAs | To assess the level of food security among urban households in Shomolu LGA, Lagos state | The results showed that food insecurity was found to be positively associated with indicators of poverty among urban households | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 66.2% | 306 households |

| [92] | Kwara state | Farm households in 20 villages. | To assess the effect of sustainable land management (SLM) technologies on farming households’ food security in Kwara state | The study revealed that to reduce the effect of food insecurity, the effective coping strategies adopted by the households include a reduction in the quantity and quality of food consumed, off-farm jobs, and the use of money proposed for other purposes to buy foods | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Insecurity Index (per capita food expenditure) Approach (food security line = NGN 4219.787) | 65.0% | 200 households |

| [93] | Ogun state | Rural community of Ode-Remo | To assess food security and dietary diversity among adults in a rural community in Remo, Ogun state | The study revealed that only 43.6 per cent of the respondents were food secure, while 43.4 per cent were severely food insecure, 30.3 per cent were moderately food insecure, and 26.3 per cent were mildly food insecure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 56.4% | 134 adults |

| [94] | Enugu and Imo states | Undergraduate students of 2 universities in Enugu and Imo states | To assess the prevalence of food insecurity and associated factors among university students among students in Enugu and Imo states | The study found that food insecurity was significantly associated with monthly allowance, daily amount spent on food, and source of income | Survey (Cross-sectional) | 10-item USDA HFSSM Approach | 80.7% | 398 university students |

| [95] | Osun and Oyo states | Working poor households in 6 towns in both Ogun and Oyo states | To examine the factors influencing the food insecurity status of the working poor households in southwest Nigeria | The study showed that more than half of the respondents were working poor households, with more than four fifths of them being food insecure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | Working poor: severely food insecure (85.7%). Working non-poor: severely food insecure (12.3%) | 284 households |

| [96] | Anambra and Imo states | Households that have experienced flooding in Imo and Anambra states | To assess the pre- and post-flood households’ food security status in southeastern Nigeria | The results showed that flooding affects food security negatively by increasing the number of food-insecure households to 92.8% | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA HFSSM Approach | Before flood: 66.7%; After flood: 92.8% | 400 households |

| [97] | Anambra, Enugu, and Ebonyi | Crop and livestock farming households | To assess the livelihood strategies adopted by husbands and wives within the same households for coping with climate-induced food insecurity in southeast Nigeria | The results indicated that 90% of the wives were more food insecure than their husbands (79.2%). The respondents noted that the observed changes in the climate contributed immensely to their food insecurity situation | Survey (Cross-sectional); FGD; key informant interviews (KIIs) | USDA HFSSM Approach | Wives: 90%; Husbands, 79.2% | 120 pairs of spouses (husbands and wives) |

| [50] | Benue state | Rural farming households in 6 LGAs of Benue state | To assess the food security status of rural farming households in Benue state | The results revealed that 49.7% of the rural farming households acquired 2100 Kcal and above per capita per day and were, therefore, classified as food secure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2100 kcal) | 56.9% | 360 rural households |

| [98] | Nigeria | Male-headed and female-headed households | To investigate food (in)security and poverty dynamics amongst male-headed and female-headed households in Nigeria | The study found that female-headed families are more vulnerable to higher incidences of food insecurity than male-headed households, and with an overall significant urban food security advantage compared to rural areas | General Household Survey (GHS) cross-sectional panel data | 12 months and 7 days recall of food shortages or inadequacy | MHHs: 2010—National (28.2%) 2012—National (25.0%) FHHs: 2010—National (34.6%) 2012—National (43.0%) | 5198 households |

| [99] | Abuja; Abia and Enugu; Rivers; Ogun and Oyo | Cassava farming households | To investigate the effects of social capital on the food security of cassava farming households | The results revealed that membership density, cash, and labour contribution significantly affected food security in the study areas | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Insecurity Index (per capita food expenditure) Approach | 59.0% | 775 households |

| [39] | Ogun state | Households in Odeda LGA of Abeokuta | To assess the household food insecurity status and coping strategies in Abeokuta, Ogun state | The results revealed that only 15.6% of the households were food secure, while the majority (84.4%) of respondents were food insecure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) | 84.4% | 250 households |

| [100] | Kaduna and Kebbi; Niger and Nassarawa; Taraba states | Maize farmers | To analyze the effect of adopting six Agricultural Practices with CSA Potentials (AP-CSAPs) on the food security status of maize farmers from northern Nigeria | The study showed that 37.0% of the farm households were food insecure, while adoption of the AP-CSAPs was generally low | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA HFSSM Approach | 37.0% | 238 households |

| [101] | Enugu state | Female-headed farming households | To examine the food security situation of female-headed households in Enugu state, Nigeria | This study revealed that poverty was found to be a major cause of food insecurity among female-headed households | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Perception of food security situation (using monthly food expenditure) in comparison to that of last year (2018) | Much worse, 25.7%; A little worse now, 47.0%; same, 14.3%; | 72 FHHs |

| [102] | Borno state | School-aged adolescent girls | To determine the level of food security and hygiene among adolescent girls in the study area | The study revealed a high prevalence of low food security among adolescent girls | Survey (Cross-sectional) | 9-question food security questionnaire | 92.7% | 562 school-aged adolescent girls |

| [103] | Kaduna state | Smallholder households | To examine the effect of smallholder socioeconomic characteristics on farming households’ food security in northern Nigeria | The findings indicated that the majority of households had low incomes and low educational attainment, which usually affects food security | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Income level, education attainment, and government policy | 81.7% | 120 households |

| [104] | Nigeria | Households in rural and urban Nigeria | To investigate the effects of non-seasonal food price volatility on household food security in Nigeria | The results revealed that imported rice price increases are damaging to both dietary diversity and the food share of consumption expenditure | General Household Survey (GHS) cross-sectional panel data | HDDS and share of food in total household expenditure | 57.0% | 4892 households |

| [105] | Anambra state | Households living in Ukpo, Ichida, and Awka | To examine food security status, associated factors, and coping strategies employed by households in Anambra state | The findings indicated that large households and those whose mothers had only primary or secondary education were more likely to be food insecure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA HFSSM Approach | 61.0% | 657 households |

| [106] | Nigeria | Households in rural and urban Nigeria | To examine the food security status of households during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria | The findings revealed that 12% of the households were food secure, with 88% in varying degrees of food insecurity | Secondary data: COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey (COVID-19 NLPS) | FAO’s FIES Approach | 88.0% | 1821 households |

| [107] | Enugu state | Households in Enugu | To determine the food security status and its predictors among households in Enugu state | The results showed that major factors influencing the food security status of households include wealth index and cooperative society membership | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Adapted freedom from hunger or food security scale | 61.1% | 800 households |

| [108] | 16 states | Smallholder maize and rice farming households in 192 communities | To examine the roles of women’s empowerment and how land tenure property rights (LTPRs) influence household food security among farmers in Nigeria | The findings showed that households that have a share of farmland on purchase and who also participate in off-farm activities are likely to be food secure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA 18-question HFSSM Approach | 74.5% | 1152 households |

| [109] | 7 northern states | Farmers in 84 rice-growing communities | To examine LTPRs among smallholder rice farmers in northern Nigeria and their influence on household food security. | The results revealed that land titling is not endogenous in the estimated models, and that household food security is largely enhanced with an increase in shares of freehold and leasehold in the households’ farmlands | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA 18-question HFSSM Approach | 73.9% | 547 farmers |

| [29] | Nigeria | Rural households in Nigeria | To assess the dynamics of food insecurity among rural households in Nigeria using panel data | The results revealed that 44% of households that were food secure in the first panel transited into food insecurity in the second panel, while 32.5% that were mildly food insecure transited into food security | General Household Survey (GHS) cross-sectional panel data | HFIAS Approach | 64.9% | 3022 rural households |

| [110] | Nigeria | Rural households in Nigeria | To assess the dynamics of food insecurity among households in rural Nigeria | The study revealed that food insecurity status increased with large family size, dependency ratio, being female-headed, and ageing household heads | General Household Survey (GHS) cross-sectional panel data | HFIAS Approach | First panel: 36.9%; Second panel: 53.5% | 3022 rural households |

| [46] | Ogun state | Maize farmers | To assess food security and its drivers among maize farming households in Ogun state | The study showed 23.2% food insecurity, while 5.5% and 1.8% of households were found to have depth and severity of food insecurity, respectively | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Insecurity Index (per capita food expenditure) Approach (food security line = NGN 2643.66) | 23.2% | 250 households |

| [111] | Oyo state | Cassava farming households | To assess food insecurity among farming households in rural Oyo state | The results revealed that 12.8% of the farming households were food secure, while 87.2% had varying levels of food insecurity | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 87.2% | 211 households |

| [112] | Oyo state | Households having under-5 children in Ibadan | To evaluate household food security and nutritional status of under-5 children in Ibadan, southwestern Nigeria | The study showed that even though households may be above the severe hunger status, the quality of the diet may be insufficient to provide needed nutrition for the health security of household members, especially under-5 children | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 63.0% | 707 households (Mothers with under-five children |

| [113] | Nigeria | Adult Nigerians | To identify factors associated with financial insecurity, food insecurity, and poor quality of daily lives of adults in Nigeria during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic | The study reported that 2487 (56.0%) were financially insecure, 907 (20.4%) had decreased food intake, and 4029 (90.8%) had their daily life negatively impacted | Online survey (Cross-sectional) | Food intake | 90.8% | 4439 households |

| [40] | Nigeria | Rural and urban Nigerian adults | To assess the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on economic and behavioural patterns related to food access. | The study revealed that even though smaller households had higher food expenditure claims than larger households, the larger the household, the more serious the challenge of economic access to food | Online survey (Cross-sectional) | FIES Approach | 42.3% | 883 households |

| [114] | Kwara state | Farming households | To evaluate the effect of climate-smart agricultural practices (CSAP) on the food security of farming households in the Kwara state | The results revealed that crop rotation is the most used CSAP in the study area, and that 16.7% of the respondents are low users, 53.33% medium users, and 30% high users of CSAP | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Insecurity Index (per capita food expenditure) Approach | 41.1% | 90 farming households |

| [115] | Gombe and Osun states | 6–19-year-old school-aged children | To assess the associations between household food insecurity, dietary diversity, and dietary patterns with the double burden of malnutrition | The results indicated that the median dietary diversity score was 7.0. Two dietary patterns (DPs) were identified. Traditional DP was significantly associated with both thinness and overweight/obesity | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 47.3% | 1200 participants |

| [116] | Plateau state | Households in 3 communities of Langai district | To assess the level of food security and its sociodemographic determinants among rural households | The results showed that significant predictors of household food security include women earning more than the basic monthly wage, those without marital partners, smaller household sizes, and those not receiving financial support | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Food Consumption Scores (FCS) | 21.4% | 201 households |

| [117] | Nigeria | Nigerian households | To examine the interrelationship among gender, empowerment, and households’ food security status in Nigeria | The findings indicated that the level of empowerment is generally low in Nigeria (21.63%), but it is much worse among the female gender (11.78%) | Secondary data: a cross-sectional dataset from the 2018/2019 Living Standard Measurement Survey | Dietary diversity score | 31.1% | 4979 households |

| [60] | Nigeria | Nigerian households | To examine perceived changes in food security as well as finances and revenue of rural and urban households during the Covid-19 pandemic in Nigeria | The study revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the food security situation of both rural and urban households and that it has also adversely affected rural and urban household finances | Secondary data: Nigeria COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey | 3-question household food insecurity | 83.0% (urban); 78.0% (rural) | 1950 households |

| [61] | Nigeria | 18 years and above adults | To assess if there were significant differences in the adoption of COVID-19 risk-preventive behaviours and experiences of food insecurity of people living with and without HIV in Nigeria | The results revealed that, in comparison with those living without HIV, PLWH had higher odds of cutting meal sizes as a food security measure and lower odds of being hungry and not eating | Online survey (Cross-sectional) | Adapted USDA HFSSM (2-question) | 29% | 4471 participants |

| [118] | Adamawa, Akwa Ibom, Anambra, Benue, Kaduna, Lagos, Enugu, Nasarawa, Gombe, and Niger states | Women and girls living with or at high risk of acquiring HIV | To advance understanding of the economic impact of COVID-19 on WGL&RHIV and to identify the factors associated with food insecurity | The findings revealed that being a member of the key and vulnerable groups was strongly associated with food insecurity, financial vulnerability, and housing insecurity, regardless of HIV status | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Adapted 1-question food security approach | 76.1% | 4355 respondents |

| [119] | Anambra, Ebonyi, and Enugu states | Selected households from the 3 states | To access the perceived effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security in southeast Nigeria | The study found that the percentage rate of food consumption of the households before the pandemic was higher relative to the COVID-19 event | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach | 75.6% | 209 households |

| [120] | Nigeria | Nigerian rural and urban households | To examine the joint influence of land access and the gender of the household head on household food insecurity | The results showed that female-headed households (FHHs) are more food insecure than male-headed households | General Household Survey (GHS) cross-sectional panel data | Self-assessment measure of household food consumption | Male: 23.7%; female: 43.1% | 4581 households |

| [121] | Enugu state | Male and female household heads in three LGAs (Oji River, Enugu East, and Uzo-uwani) of Enugu state | To assess the household food and nutrition security among households in Enugu state | The study indicated that the FGT model results for the headcount ratio showed only 22% of households were food secure during the COVID-19 pandemic | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2100 kcal) | 78.0% | 480 households |

| [122] | Oyo, Ekiti, and Ogun states | Rural farming households in the three states | To evaluate the determining factors of rising food expenditure, implications for food security, as well as households’ coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic | The study indicated that the FGT model results for the headcount ratio showed only 22% of households were food secure during the COVID-19 pandemic | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach (2100 kcal) | 78.0% | 480 households |

| [123] | Rivers and Bayelsa states | Farming households in the Niger Delta region | To investigate how vulnerability to the “triple challenge” affects food security among farming households in the Niger Delta region | The results revealed that vulnerability to the “triple challenge” increases the probability of being in a severe food insecure state, particularly for households with a high dependency ratio | Survey (Cross-sectional) | FIES Approach | 72.2% | 503 households |

| [19] | Ogun and Oyo states | Smallholder cassava farming households | To investigate food insecurity, health and environment-related factors, and agricultural commercialization among smallholder farm households | The findings revealed that less than 20%, 30%, and 40% of households in all four food insecurity categories had access to piped water, improved toilet facilities, and electricity, respectively | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 90.9% | 352 households |

| [124] | Oyo state | Smallholder gari processors | To evaluate food security status and highlight survival strategies used by gari processors in Oyo state | The findings revealed that none of the gari processing households in Oyo state were found to be food secure | Survey (Cross-sectional) | USDA approach: 18-question HFSSM | 100% | 120 gari processors |

| [125] | Niger state | Preschool children | To assess the household food security and feeding patterns of preschoolers in Niger state, Nigeria | The study showed that 59.8% of the preschoolers met their minimum dietary diversity, but 98.8% of the children were from food insecure households | Survey (Cross-sectional) | HFIAS Approach | 98.8% | 450 participants |

| [126] | Kogi state | Cashew farming households | To assess the household food insecurity status of cashew farming households in Kogi state | The study indicated that food security status was determined by household size, farming experience, education level of households, annual off-farm income, output of cashews, and output of cereals | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Recommended daily calorie required approach | 58.8% | 228 participants |

| [41] | Benue, Delta, Ebonyi, and Kebbi states | Nutritionally vulnerable smallholder households | To investigate the effects of COVID-19 on food security and dietary diversity of households in Nigeria | The results showed that income losses due to the COVID-19 restrictive measures had pushed households into more severe food insecurity and less diverse nutritional outcomes | Phone survey | FIES Approach | Pre-COVID-19: 43.0%; During COVID-19: 93.1% | 1031 households |

| [127] | Oyo, Lagos, Abuja, and Plateau states | Households representing different income groups | To examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security and psychosocial stress among households in selected states in Nigeria | The study revealed that variables like gender, educational level, and work hours per day were associated with food security and hunger due to COVID-19 | Survey (Cross-sectional) | Modified FIES Approach | 95.8% | 412 households |

| [128] | Nigeria | Nigerian rural and urban households | Nigerian rural and urban households | The study revealed a significant increase in the prevalence of food insecurity in Nigeria during the COVID-19 crisis | COVID-19 National Longitudinal Phone Survey (NLPS) | FIES Approach | Pre-pandemic period: 36% Period of COVID-19: 74.0% (2nd wave), 72.0% (4th wave) | 1674 households |

| [129] | Northeastern Nigeria | Rural households | To analyze the food security status of rural households in northeastern Nigeria | The results showed that more than half of the selected households were food secure in both waves, but not so in the case of DDS | General Household Survey (GHS) | Mean per capita food expenditure (MPCE) and DDS | MHs, 41.3%; FHs, 84.6% (wave 2); MHs, 38.3%; FHs, 61.7% (wave 3) | 902 households |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Otekunrin, O.A.; Mukaila, R.; Otekunrin, O.A. Investigating and Quantifying Food Insecurity in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13101873

Otekunrin OA, Mukaila R, Otekunrin OA. Investigating and Quantifying Food Insecurity in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. Agriculture. 2023; 13(10):1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13101873

Chicago/Turabian StyleOtekunrin, Olutosin Ademola, Ridwan Mukaila, and Oluwaseun Aramide Otekunrin. 2023. "Investigating and Quantifying Food Insecurity in Nigeria: A Systematic Review" Agriculture 13, no. 10: 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13101873

APA StyleOtekunrin, O. A., Mukaila, R., & Otekunrin, O. A. (2023). Investigating and Quantifying Food Insecurity in Nigeria: A Systematic Review. Agriculture, 13(10), 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13101873