1. Introduction

The world’s cheese production has grown steadily in the last five years to reach 21 mln t in 2019 [

1]. Relevant activities do not only stimulate milk-focused agriculture and create new job opportunities, but also facilitate a joint growth of eco- and rural tourism [

2,

3]. Cheese production thus contributes significantly to re-vitalizing rural communities, and it is consequently beneficial for local agricultural development and rural life. Although a recognizable environmental impact of cheese production (waste, CO

2 emission, over-grazing, etc.) has been established recently [

4,

5,

6], the currently rising demand for tourism activities may well help to counteract these negative consequences by stimulating the implementation of a more responsible and ecologically sustainable practice of cheese production. All these considerations underline the importance of research into the strategic management of cheese production.

Russia is one of the most important world producers and consumers of cheese; the annual production and consumption rates in 2019 were 0.97 and 1.22 mln t, respectively [

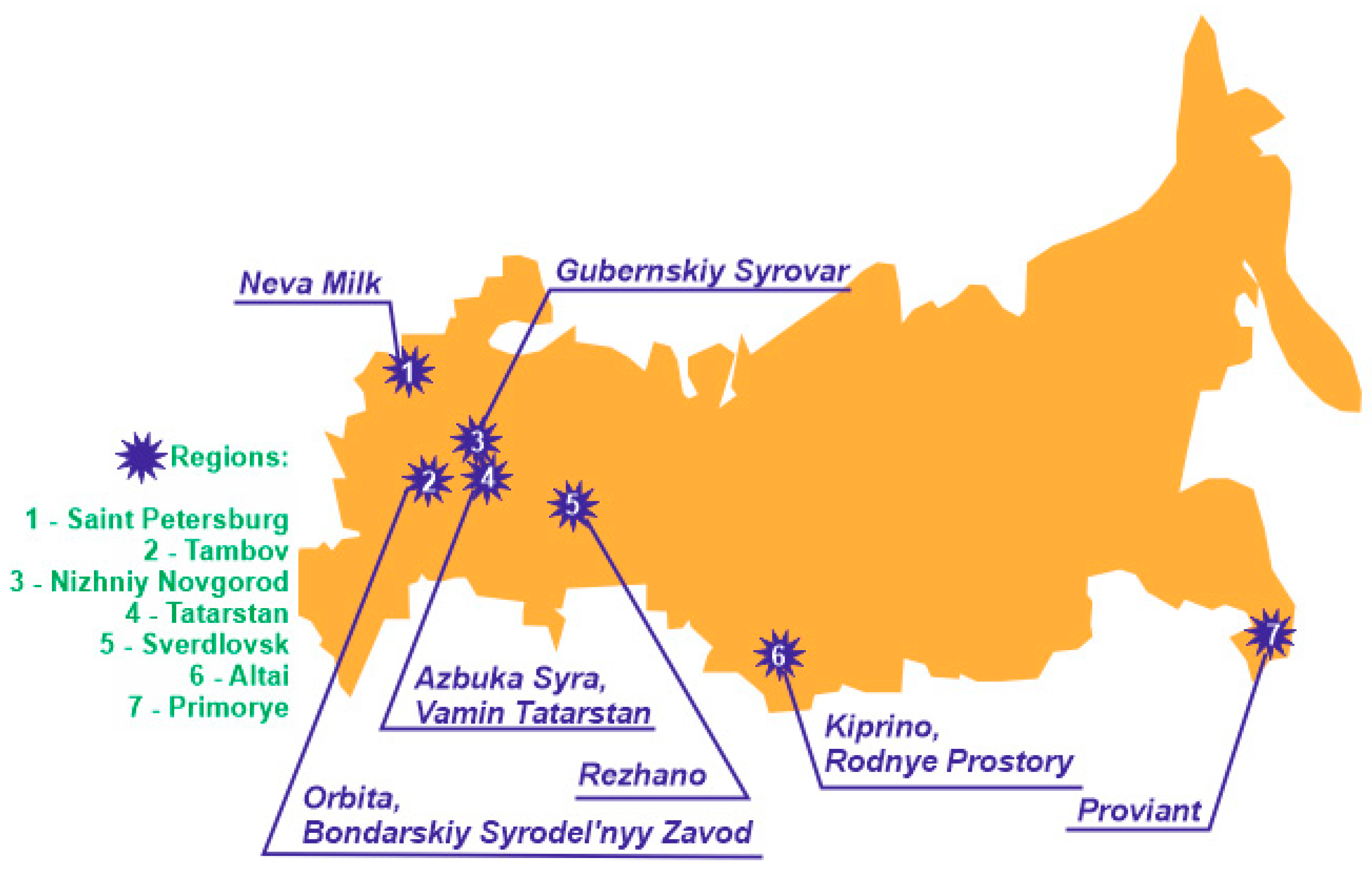

1]. The main areas of cheese production are located in the centre and the south of the European part of the country, as well as in southern Siberia; these are important centres of milk agriculture, and cheese tourism has already started to grow and to change rural life there [

7]. The National Dairy Producers Union (’Soyuzmoloko’) makes significant efforts to co-ordinate the attempts of the Russian business community of milk and cheese producers to further improve the performance of this industry. The union is particularly deeply involved in the organization of exhibitions and in the discussion of various initiatives, as well as in project support and promotion; it is also efficient in providing analytical material. Moreover, the union might contribute to teaching the principles of strategic management to Russian cheese producers and to the exchange of relevant experience/knowledge.

Various economical, medical, and technological aspects of the Russian cheese-production industry are discussed in the studies by Ermolaev et al. [

7], Martinchik et al. [

8], and Yormirzoev et al. [

9]. However, strategic management in the organizations of this industry still lacks investigation by scholars, however urgent this may be. This is unfortunate because well-developed and well-balanced strategic management is required if Russian cheese producers are to perform better on a national scale in a context of strengthened competition, extending export opportunities, effective communication with agricultural enterprises and retail companies, evolving relations with local communities, and demand for environmental responsibility. Consequently, cheese producers need good strategic decisions to perform better in a community where organizational [

10,

11,

12,

13], socio-economical [

14,

15], and environmental sustainability [

16,

17,

18] jointly play an increasingly important role. Particularly, they need to secure steady business growth, create jobs, and sustain environmental health through minimizing any negative impacts of their enterprises, but also by attracting ecotourists.

The present contribution aims at filling the gap. Its main objective is to provide a first analysis of the missions stated by the Russian cheese-producing enterprises. The outcomes of this study should help in clarifying the relevance of the organizations’ intentions to the interests of the rural communities.

2. Materials and Methods

Mission statements are an important tool for strategic management since they provide a brief explanation of general goals, intentions, and priorities of a given enterprise to be shared and followed by managerial and other staff [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. They are consequently also important for customers, partners and competitors, i.e., they serve as instruments positioning an enterprise or organization in the market. When mission statements by several organizations from the same industry are analyzed and mutually compared, this allows for judgment of the industry’s strategic priorities, as well as the homo- or heterogeneity within the industry. Such an analysis and comparison can be performed since mission statements are often provided on-line, i.e., on official web-pages of organizations. About three decades ago, Pearce and David [

24] demonstrated the efficiency of such an analysis of mission statements, and a series of studies based on these principles now constitute the basis for a new direction of strategic management research [

19].

For the purpose of the present study, provisional lists of the Russian cheese producers were compiled on the basis of information that can be found scattered on the Russian Internet. The authors’ own knowledge and experience with the common cheese-related brands and trademarks formed an additional source of information. Although these methods of information searching cannot be considered as optimum, they appeared to be the only possibility in this case, where the relevant knowledge is unavailable in a systematic form. The name of each Russian cheese-producing company found was searched on the Internet for information on their official web-pages regarding mission statements. A total of 10 such statements were found, and these were used all for further analysis (

Table 1). Although this number of mission statements is relatively small, it seems sufficient for the present pioneering, tentative analysis, as they include some important producers that represent different, commonly agriculture-focused, regions of Russia (

Figure 1).

All organizations dealt with in our further analysis are industrial producers, which is not surprising as industrial cheese production dominates in Russia. However, these producers still have a close affinity to rural areas, and their official web-pages often address rural resources and a rural lifestyle. Moreover, some organizations are located in truly agricultural areas. To avoid reputation-related issues, the various mission statements are treated anonymously in the present study so that they cannot be associated with a specific organization; the order of the organizations in

Table 1 does consequently not correspond to the order of the mission statements analyzed below.

The mission statements on the organizations’ official web-pages are given in Russian, and the first step in their analysis was therefore their careful translation into English. Subsequently, the content of each statement was analyzed following the principles of Pearce and David [

24]. These experts explained that the content of the majority of mission statements include similar blocks of information that can be classified into several principal components (see below). A strong mission statement includes at least some of these components, and the most informative statements include all components. Recognition of these components in the available mission statements is possible by qualitative content analysis, i.e., finding words and expressions relevant to these components. This approach is used widely in modern strategic management research, irrespective of industry and business size [

19,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. The ’standard’ principal components, proposed initially by Pearce and David [

24], were soon updated by David [

30]. These are as follows: customers (CUS), markets (MAR), image (IMA), products and/or services (PRO), technology (TEC), survival, growth, and profitability (SGP), philosophy (PHI), self-understanding (SUN), and employees (EMP). The content of all mission statements of the Russian cheese producers has been analyzed qualitatively for identification of these components. The subsequent summary of these findings allowed further interpretation of the strategic priorities.

Two aspects regarding the above need further comment. First, the SGP component is present directly and indirectly in (almost) all mission statements, irrespective of the company’s size and performance [

24]. To avoid unduly speculative judgments in the present study, this component is recognized in only those cases where the relevant ideas are stated explicitly and precisely. Second, the PHI component deals with very general issues, including social responsibility and environmental concerns. Consequently, the precise content of this component may differ substantially between the various statements.

3. Results

Mission No. 1: We create brands, which each Russian family trusts and loves. In this statement, brands and trust refer to image. The market is defined as the complete community of Russian consumers. The appeal to families and love-triggered production are relevant to philosophy.

Mission No. 2: The cheese-making enterprise is a team of professionals making a natural, useful, nutritious, delicious, living product with love, for family joy, health, and wellbeing. Consideration of the enterprise is a kind of self-understanding. The product, i.e., cheese, is indicated directly. The team of professionals refers to employees. Production with love and the appealing characteristics of the product constitute philosophy. Finally, the list of distinctive characteristics of the product indicates how this product should look in the eyes of the customers, i.e., this is the IMA component.

Mission No. 3: To care about each customer, offering a natural and delicious product. The focus in this statement places emphasis on the customers and the product. Such emphasis on the natural essentials of the product refers to a kind of environmental philosophy.

Mission No. 4: Leadership in the market of cream cheese producers. This statement differs somewhat from the other ones, as it focuses on business ambitions. Leadership refers to firm performance, i.e., the SGP component. The product is indicated directly. Finally, the market is defined not geographically, but as a segment of the industry.

Mission No. 5: To form a culture of cheese consumption in Russia showing, through our own performance, a level of production quality that is not below the European standards. To introduce quality and useful products to the meal of a Russian customer, which provide a diversity of flavours and healthy nutrition for the entire family. This statement is lengthy and very comprehensive. As many as six components are identified in it. Customers and the Russian market are indicated. Image is linked to the desired perception of high, European-level quality. The product (cheese) is mentioned by name. Philosophy is determined as the intention to offer something unique and very important to Russians. Mentioning ’own performance’ is a reference to self-understanding.

Mission No. 6: We have started production with modern equipment and preserve all the natural best! The organization highlights self-understanding by explaining its purpose. Modern equipment is equated with sophisticated technology, and preservation of the natural best is a kind of environmental philosophy.

Mission No. 7: To produce dairy products which are the best with regards to quality and safety, and which match the customers’ demands and national laws, as well as the company’s quality standards. The statement refers to the customers, although it does not explicitly name them (this is the same as in numerous other statements). Attention to quality and safety as perceived by the customers implies focus on image. The product is named, although generally (dairy products). The functioning of the organization through meeting the customer’s demand and following own standards reflects the SGP component. The same consideration of own standards can be interpreted as a sign of self-understanding. Of special interest is the remark concerning national laws. It is difficult to relate this to any ’standard’ component, and we tentatively attribute this part of the statement to image: most probably, the organization wishes to impress the customers by the suggestion of the protection of both employees and customers by following the law.

Mission No. 8: Do good. Eat well. This slogan-sounding statement consists of one single component: philosophy. The appeal is brief and general, and refers to some basic societal values. Although ’doing good’ can also be linked to the organization’s image, such an attribution seems to be too vague.

Mission No. 9: To produce quality food at an appropriate price for all workers. To not use chemicals. To allow minimal damage to the environment using recycled material. The statement is socially and environmentally oriented, which stresses the dominance of the PHI component. Avoiding chemicals and recycling material are peculiarities of the production process, which makes the TEC component well-visible. Apparently, the reference to quality is not given in this case in the context of desired image; quality is treated as a basic characteristic of the product for the nutrition that people deserve. The expression ’each worker’ means ’all the customers’, although it is defined broadly.

Mission No. 10: To provide delicious and quality dairy products to everybody. The general nomination of the product is mentioned. Its characteristics (especially ’delicious’) can be linked to image. ’Everybody’ can be understood as ‘customers’. Finally, accessibility of the product for everybody can be interpreted as a socially higher task, i.e., this is the PHI component.

4. Discussion

The content of the analyzed mission statements from the Russian cheese-making industry is summarized in

Table 2. This information leads to the following considerations. First, the statements show significant differences, which indicates the heterogeneity of the strategic priorities of the organizations involved. Second, the average number of principal components in statements is 3.7, which means a moderate diversity in content, i.e., all organizations (with one exception) include several priorities, though not all. Third, the most attention is paid to philosophy (80% of the cases) and product (70%), and the least important seems to be employees (just one case). Surprisingly, technology, a peculiarity which is essential for cheese production, and business performance (SGP), which needs attention in the rapidly evolving market, seems also to be of only minor importance to the majority of the organizations. These findings imply that Russian cheese producers have an adequate strategic understanding. Moreover, a certain heterogeneity in the cheese-making industry appears to be present, i.e., the industry as a whole does not develop coherent priorities. However, the strategic statements can be considered as advanced because they allow easy recognition of all components that are characteristic of an international-level business, although the various organizations are small to intermediate, operating nationally or regionally. This indicates the strength of the modern Russian food industry and the related agriculture.

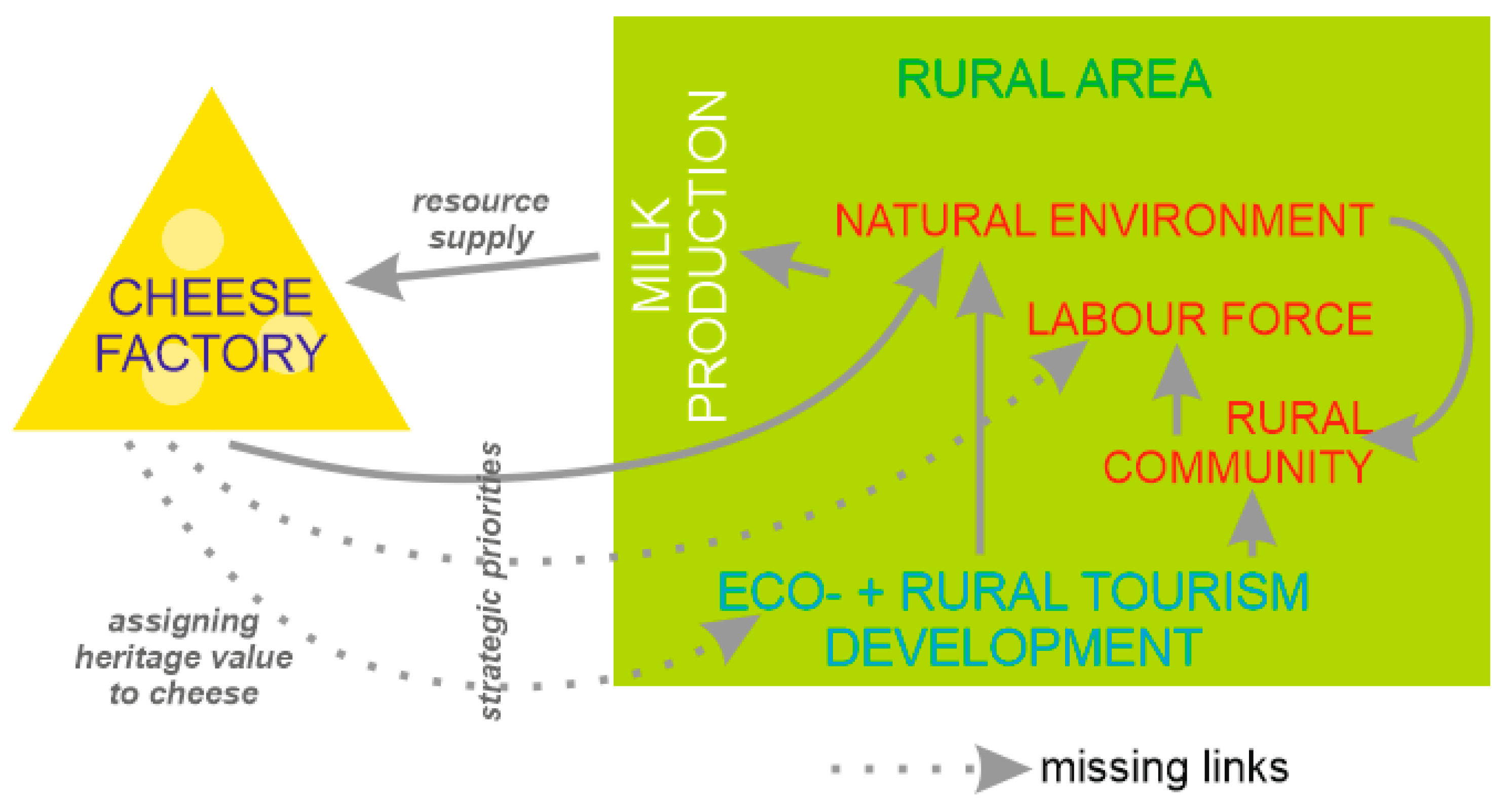

Some of the cheese-producing organizations are situated in large cities. However, the enterprises themselves are often located in rural areas of the same regions or, at least, depend on milk supply from these areas. This means that the strategic priorities of these organizations should be relevant in some way to the needs of the rural communities. Aleksandrov and Fedorova [

31], Bozhkov and Trotsuk [

32], Polushkina et al. [

33], Shirokalova and Deriabina [

34], and Wengle [

35] have shown that the Russian agriculture and rural population faces challenges and transformations, and that they need support. The three most important issues are new jobs, new professional skill development, and ’greening’. Although cheese-producing enterprises are small or intermediate in size, each of them can employ up to 20–30 people with competitive salaries, which is really important for Russian rural communities, where jobs may be scarce and where average salaries are lower than in cities. As cheese production in Russia is a rising industry with active implementation of innovations, while it depends, at the same time, on rural resources, one would expect that some strategic priorities of the analyzed organizations would address the rural communities. This is true, however, only in part (

Figure 2). On the one hand, some mission statements include some environmental philosophy (see above). The intent to apply ’green’ technologies (Mission No. 9) and the common designation of cheese as a natural product implies a reference to ecology-friendly, responsible exploitation of rural resources. This matches the current agenda of Russia regarding its agricultural and rural area development, where eco-innovations, energy-saving initiatives, decrease in the use of hazardous chemicals, etc. are implemented [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. On the other hand, employees are addressed in only one case (Mission No. 2) and not in relation to the rural community or job opportunities. Most mission statements include a PHI component (

Table 2), and the organizations tend to support social responsibility. This last issue is aimed at potential customers and Russian society in general. Nothing is mentioned regarding rural life. On the basis of this evidence, it is inferred that the strategic priorities of Russian cheese producers are biased in their relevance for rural communities (

Figure 2). A study by Weinfurtner and Seidl [

42] emphasized the idea of space in management. As far as the mission statements of the Russian cheese producers are concerned, it is evident that some of them tend to deal with country-level distances (Missions No. 1 and 5) but lack a local focus. In other words, these statements are aimed at the entire Russian space.

As mentioned above, cheese production seems to be a factor enabling the coupling of eco- and rural tourism development in some areas of the world [

2,

3], and Russia has significant resources for this kind of tourism [

7]. Although these resources are still in the initial stage of exploitation, examples of successful tourism activities in various regions are already available, including cheese-tasting events and excursions to cheese-producing factories. Indeed, cheese tourism can contribute to the growth and diversification of domestic tourism in Russia. Such activities can bring certain advantages to rural communities in the form of jobs, environment, infrastructure, and cultural exchange. Some of the cheese producers dealt with in the present study already offer various types of tourism activities (

Table 3). However, the potential of cheese tourism should (and can) be exploited in Russia much more intensively [

7].

Obviously, expecting attention to tourism opportunities in the mission statements would not be justified. However, in order to start tourism activities, the heritage value of cheese itself and traditions related to its production needs more support, particularly when these aspects are already used for the purposes of tourism. This is the case in many countries, including Italy [

43], France [

44], Portugal [

45], and China [

46]. Careful analysis of the available mission statements reveals that none of them treats cheese as a heritage. Nonetheless, some strategic statements designate cheese as a very special product, and one statement (Mission No. 1) emphasizes cheese brands. These are appropriate premises for further appreciation of the heritage value of Russian cheese. Another important aspect of the problem is linked to cooperation. The development of cheese tourism requires cheese producers to be ready for cooperation with the various stakeholders and for involvement in complex projects with significant social and environmental responsibility. The analyzed mission statements do not reflect these relevant issues. However, the frequent presence of the PHI component in the mission statements (

Table 2) means that Russian cheese producers are able to face higher tasks, which indicates the willingness of the management to look beyond the present frontiers of mere production.

A main point of interest is the position of mission statements in the on-line communication of company-related information. Examination of the official web-pages of the analyzed cheese producers indicates that these statements are commonly placed on a special (second-order) page where the business profile of the organization is detailed (

Table 4). However, some cheese producers place their mission statements on one of their main pages. This is evidence that the organizations recognize the importance of missions when communicating company-related information on-line. This is done, however, by only less than half of the organizations; the positive aspect of this is that at least these organizations recognize that mission statements are tools that may have a strong impact on both customers and the business community.

Undoubtedly, the present analysis faces some limitations. The first is the limited number of organizations that show their strategic ideas on-line. Cheese production is usually restricted to small and medium enterprises, although they are assumed to be numerous when taking into account the volume of cheese produced annually in Russia [

1]. It is therefore advisable that further research should consider strategic declarations from more organizations, but these documents cannot be found on-line and thus may only be obtained from the organizations themselves upon request. The second limitation is that mission statements cannot reflect the full spectrum of business development. The official web-pages of most organizations inform about other strategic elements, such as vision and company values, technical equipment and qualifications of the employees, and preferred worker characteristics. It therefore seems important to extend future research to a full-scale content analysis of the on-line business profiles of Russian cheese producers. Visions, company values, and some other strategic statements should all be analyzed. Additionally, the strategic attitudes of managers might be examined through interviews and questionnaires. Such research may shed more light on the question of which tourism-related opportunities are considered by these producers and to what extent the responsible managers are ready to interact with rural communities. A clear distinction should be made, however, between strategic statements and on-line company promotion. Missions are stated by managers, whereas strategy-related information available on web-pages may be informal and written by web-page developers. Consequently, such texts have little or nothing to do with the real company strategy.

5. Conclusions

The above analysis leads to the conclusion that Russian cheese producers have different priorities for their organizations, often focusing not only on their products but also on higher objectives (philosophy). Their strategic statements are relevant to rural communities because they pay attention to environmental issues, but in general the focus is not on the rural community. Russian cheese producers demonstrate a significant strategic potential, and further refining of their missions may bring this potential to an even higher level, as well as their business performance.

The outcomes of the preset study have three practical implications. First, the mission statements should include a larger number of the ’standard’ components. This means that the owners/top managers of the cheese-producing organizations should learn and follow the principles of modern strategic management in order to guide their business to a higher level. Second, they need to pay more attention to the rural community. Although the analyzed mission statements are, in many respects, rather broad, they are unduly focused on the industry itself, even though the companies strongly depend on rural resources. Third, the missions should contribute to the recognition of the heritage value of cheese produced in Russia. The experience of foreign cheese producers can be taken as an example. As far as the involvement of some Russian cheese producers in tourism activities is concerned, the recognition of the value of such a heritage seems easy to implement, and Russian society will certainly be convinced of the value considering the large cheese consumption in the country. A successful implementation of the proposed steps can be co-ordinated by the National Dairy Producers Union (’Soyuzmoloko’), which has the potential to organize nation-wide projects that may help to promote dairy products.

Despite its tentative character and certain limitations, the present analysis allows some important (though preliminary) conclusions regarding further research into the strategic management of the cheese-producing industry. The present study shows that the Russian cheese production industry has already some interesting ideas about strategic management regarding the joint interests of both the food industry and rural life. It also shows that strategic management in the Russian food industry and agriculture is significantly more diverse than is commonly presumed [

47,

48,

49]. Moreover, the mission statements of the cheese-producing organizations provide important information about the peculiarities of doing business in Russia (see also the general notes in [

50,

51]) and about the current advance in the Russian economy and its specific branches. Two important opportunities for further research (in addition to extended mission research—see above) are the realization of a better correspondence between the strategic statements and real performance of the organizations, and the analysis of the perception of these statements by business partners, competitors, customers, and rural communities.