Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel in Older Patients with NSTE-ACS Using Oral Anticoagulation: A Sub-Analysis of the POPular Age Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Study Endpoints

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patti, G.; Lucerna, M.; Pecen, L.; Siller-Matula, J.M.; Cavallari, I.; Kirchhof, P.; De Caterina, R. Thromboembolic Risk, Bleeding Outcomes and Effect of Different Antithrombotic Strategies in Very Elderly Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Sub-Analysis From the PREFER in AF ( PRE vention o F Thromboembolic Events—E uropean R egistry in A trial F ibrillation). J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.A.; Skjøth, F.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Larsen, T.B.; Kotecha, D. Temporal Trends in Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality of Atrial Fibrillation in Primary Care. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heeringa, J.; Van Der Kuip, D.A.; Hofman, A.; Kors, J.A.; Van Herpen, G.; Stricker, B.H.; Stijnen, T.; Lip, G.Y.; Witteman, J.C. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: The Rotterdam study. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valgimigli, M.; Bueno, H.; Byrne, R.A.; Collet, J.-P.; Costa, F.; Jeppsson, A.; Jüni, P.; Kastrati, A.; Kolh, P.; Mauri, L.; et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 39, 213–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaderdan, K.; Ishak, M.; Heestermans, A.A.; De Vrey, E.; Jukema, J.W.; Voskuil, M.; De Boer, M.-J.; Hof, A.W.V.T.; Groenemeijer, B.E.; Vos, G.-J.A.; et al. Ticagrelor or prasugrel versus clopidogrel in elderly patients with an acute coronary syndrome: Optimization of antiplatelet treatment in patients 70 years and older—Rationale and design of the POPular AGE study. Am. Heart J. 2015, 170, 981–985.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimbel, M.; Qaderdan, K.; Willemsen, L.; Hermanides, R.; Bergmeijer, T.; De Vrey, E.; Heestermans, T.; Tjon, M.; Gin, J.; Waalewijn, R.; et al. Clopidogrel versus ticagrelor or prasugrel in patients aged 70 years or older with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome (POPular AGE): The randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Bhatt, D.L.; Oldgren, J.; Lip, G.Y.; Ellis, S.G.; Kimura, T.; Maeng, M.; Merkely, B.; Zeymer, U.; Gropper, S.; et al. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran after PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.D.; Heizer, G.; Aronson, R.; Vora, A.N.; Massaro, T.; Mehran, R.; Goodman, S.G.; Windecker, S.; Darius, H.; Li, J.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndrome or PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1509–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallentin, L.; Becker, R.C.; Budaj, A.; Cannon, C.P.; Emanuelsson, H.; Held, C.; Horrow, J.; Husted, S.; James, S.; Katus, H.; et al. Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szummer, K.; Montez-Rath, M.E.; Alfredsson, J.; Erlinge, D.; Lindahl, B.; Hofmann, R.; Ravn-Fischer, A.; Svensson, P.; Jernberg, T. Comparison Between Ticagrelor and Clopidogrel in Elderly Patients with an Acute Coronary Syndrome: Insights from the SWEDEHEART Registry. Circulation 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewilde, W.J.; Oirbans, T.; Verheugt, F.W.; Kelder, J.C.; De Smet, B.J.; Herrman, J.-P.; Adriaenssens, T.; Vrolix, M.; Heestermans, A.A.; Vis, M.M.; et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: An open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.M.; Mehran, R.; Bode, C.; Halperin, J.; Verheugt, F.W.; Wildgoose, P.; Birmingham, M.; Ianus, J.; Burton, P.; van Eickels, M.; et al. Prevention of Bleeding in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2423–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vranckx, P.; Valgimigli, M.; Eckardt, L.; Tijssen, J.; Lewalter, T.; Gargiulo, G.; Batushkin, V.; Campo, G.; Lysak, Z.; Vakaliuk, I.; et al. Edoxaban-based versus vitamin K antagonist-based antithrombotic regimen after successful coronary stenting in patients with atrial fibrillation (ENTRUST-AF PCI): A randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, S.J.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Yusuf, S.; Eikelboom, J.; Oldgren, J.; Parekh, A.; Pogue, J.; Reilly, P.A.; Themeles, E.; Varrone, J.; et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granger, C.B.; Alexander, J.H.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lopes, R.D.; Hylek, E.M.; Hanna, M.; Al-Khalidi, H.R.; Ansell, J.; Atar, D.; Avezum, A.; et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.R.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Garg, J.; Pan, G.; Singer, D.E.; Hacke, W.; Breithardt, G.; Halperin, J.L.; Hankey, G.J.; Piccini, J.P.; et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giugliano, R.P.; Ruff, C.T.; Braunwald, E.; Murphy, S.A.; Wiviott, S.D.; Halperin, J.L.; Waldo, A.L.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Weitz, J.I.; Špinar, J.; et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2093–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeira, D.; Nunes-Ferreira, A.; Rodrigues, R.; Vicente, E.; Pinto, F.J.; Ferreira, J.J. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation: A systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2019, 81, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| OAC + Clopidogrel N = 83 | OAC + Ticagrelor N = 101 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR) | 78 (75–83) | 77 (73–81) | 0.136 |

| Male | 58 (69.9) | 70 (69.3) | 0.933 |

| Body weight < 60 kg | 6 (7.2) | 7 (7.0) | 0.952 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 (24.1) | 42 (41.6) | 0.036 |

| Hypertension | 65 (79.3) | 76 (75.3) | 0.534 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 60 (72.3) | 65 (63.3) | 0.220 |

| Current smoker | 7 (8.8) | 11 (11.1) | 0.443 |

| Family history of CAD | 23 (31.1) | 23 (25.0) | 0.384 |

| Previous medical history | |||

| Peripheral artery disease | 9 (10.8) | 11 (11.0) | 0.973 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 29 (34.9) | 26 (25.7) | 0.175 |

| Prior PCI | 21 (25.3) | 22 (21.8) | 0.575 |

| Prior CABG | 19 (22.9) | 16 (15.8) | 0.225 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 7 (8.4) | 11 (10.9) | 0.577 |

| Ischemic stroke | 5 (6.0) | 9 (8.9) | 0.462 |

| Peptic ulcer | 5 (6.0) | 4 (4.0) | 0.518 |

| COPD | 15 (18.1) | 9 (8.9) | 0.066 |

| At admission | |||

| Renal function (median, IQR) | 63.7 (48.1–77.4) | 62.7 (46.9–79.2) | 0.815 |

| eGFR < 60 | 37 (44.6) | 47 (46.5) | 0.791 |

| Haemoglobin (median, IQR) | 8.7 (8.0–9.3) | 8.5 (7.9–9.2) | 0.111 |

| Killip class I at admission | 74 (90.2) | 77 (79.4) | 0.050 |

| During hospital stay | |||

| Coronary angiography | 72 (86.7) | 86 (85.1) | 0.757 |

| Radial access site | 49 (70.0) | 56 (69.1) | 0.908 |

| Significant coronary lesion | 63 (87.5) | 78 (90.7) | 0.518 |

| multivessel disease | 46 (63.9) | 57 (66.3) | 0.906 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 33 (39.8) | 36 (35.6) | 0.566 |

| CABG | 16 (19.3) | 28 (27.7) | 0.181 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| NSTEMI | 65 (81.3) | 87 (87.0) | 0.298 |

| UA | 9 (11.3) | 5 (5.0) | |

| Type II ACS | 6 (7.5) | 8 (8.0) |

| OAC + Clopidogrel N = 83 | OAC + Ticagrelor N = 101 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 23 (27.7) | 34 (33.7) | 0.385 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | |||

| Clopidogrel | 69 (83.1) | 21 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| Ticagrelor | 0 | 57 (56.4) | |

| Prasugrel | 0 | 1 (1.0) | |

| no P2Y12 inhibitor | 14 (16.9) | 22 (21.8) | |

| Type of OAC | |||

| VKA | 62 (74.7) | 65 (64.3) | 0.113 |

| NOAC | 21 (25.2) | 36 (35.7) | |

| Triple therapy | 19 (22.9) | 21 (20.8) | 0.731 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 73 (88.0) | 94 (93.1) | 0.233 |

| OAC + Clopidogrel N = 83 | OAC + Ticagrelor N = 101 | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

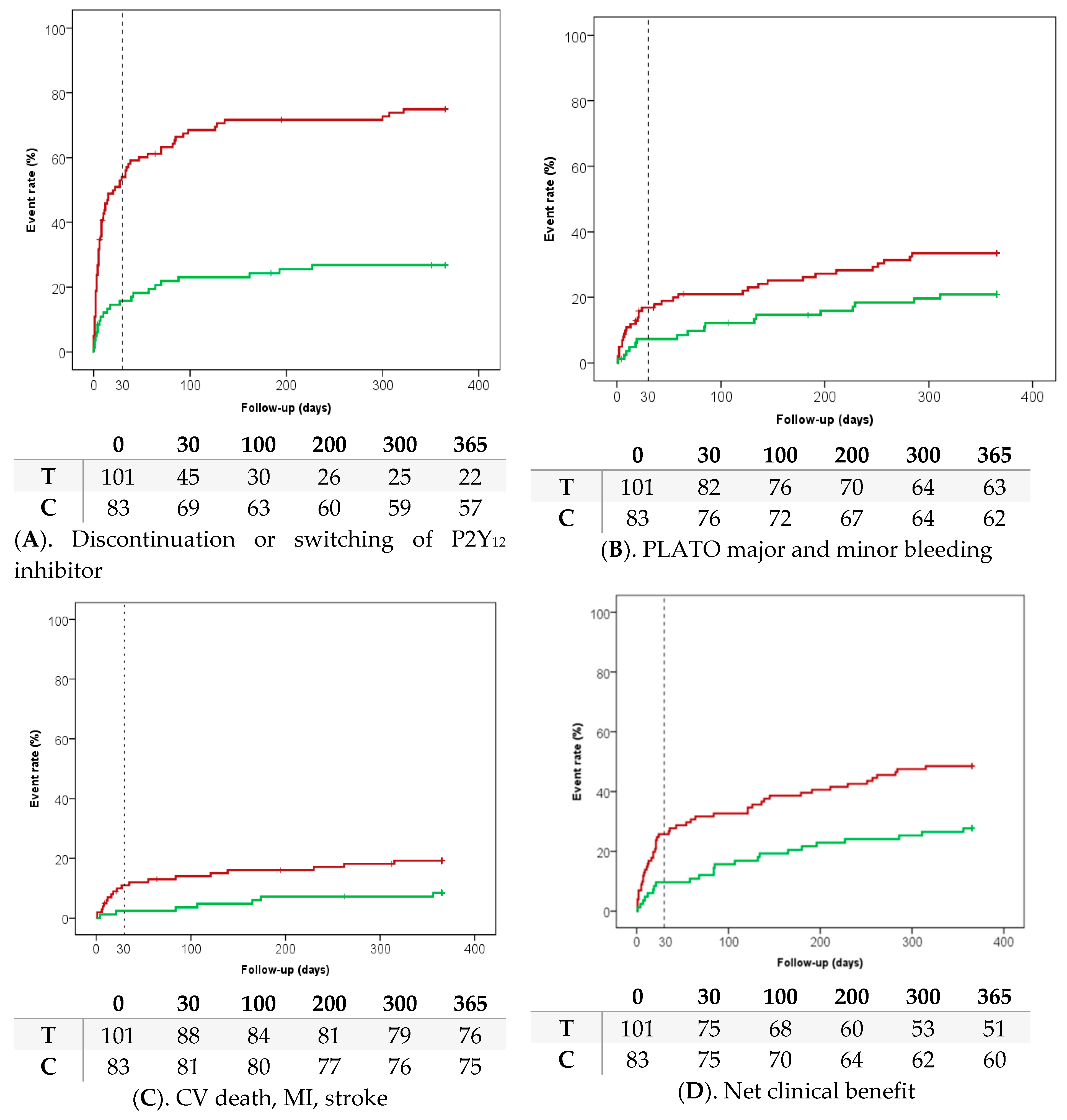

| PLATO major and minor bleeding | 17 (20.9) | 33 (33.5) | 0.55 (0.30–1.00) | 0.051 |

| PLATO minor bleeding | 10 (12.4) | 14 (14.5) | 0.80 (0.35–1.84) | 0.614 |

| PLATO other major bleeding | 6 (7.4) | 7 (7.2) | 0.91 (0.30–2.79) | 0.971 |

| PLATO major life threatening bleeding | 3 (3.7) | 12 (12.4) | 0.31 (0.09–1.12) | 0.038 |

| PLATO major bleeding | 8 (9.8) | 19 (19.6) | 0.47 (0.20–1.09) | 0.071 |

| PLATO non-CABG related major bleeding | 6 (7.4) | 14 (14.5) | 0.52 (0.20–1.38) | 0.138 |

| ICH | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.2) | 0.75 (0.07–8.30) | 0.645 |

| Fatal bleeding | 0 | 2 (2.1) | - | 0.191 |

| OAC + Clopidogrel N = 83 | OAC + Ticagrelor N = 101 | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net clinical benefit outcome | ||||

| All-cause death, myocardial infarction, stroke, PLATO major and minor bleeding | 23 (27.7) | 49 (48.5) | 0.48 (0.29–0.79) | 0.003 |

| Second net clinical benefit outcome | ||||

| CV death, myocardial infarction, stroke, PLATO major bleeding | 15 (18.1) | 35 (35.1) | 0.48 (0.26–0.88) | 0.008 |

| Thrombotic outcomes | ||||

| CV death, myocardial infarction, stroke | 7 (8.4) | 19 (19.2) | 0.48 (0.20–1.14) | 0.035 |

| All-cause death | 4 (4.8) | 12 (11.9) | 0.42 (0.13–1.32) | 0.090 |

| CV death | 2 (2.4) | 6 (6.0) | 0.45 (0.09–2.27) | 0.237 |

| Myocardial infarction | 5 (6.2) | 11 (11.5) | 0.60 (0.21–1.74) | 0.202 |

| Unstable angina | 0 | 1 (1.1) | - | 0.346 |

| Ischemic stroke | 1 (1.2) | 4 (4.1) | 0.30 (0.03–2.77) | 0.236 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 1 (1.2) | 0 | - | 0.287 |

| Stent thrombosis | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Urgent revascularisation | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.1) | 0.74 (0.07–8.18) | 0.641 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gimbel, M.E.; Tavenier, A.H.; Bor, W.; Hermanides, R.S.; de Vrey, E.; Heestermans, T.; Gin, M.T.J.; Waalewijn, R.; Hofma, S.; den Hartog, F.; et al. Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel in Older Patients with NSTE-ACS Using Oral Anticoagulation: A Sub-Analysis of the POPular Age Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103249

Gimbel ME, Tavenier AH, Bor W, Hermanides RS, de Vrey E, Heestermans T, Gin MTJ, Waalewijn R, Hofma S, den Hartog F, et al. Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel in Older Patients with NSTE-ACS Using Oral Anticoagulation: A Sub-Analysis of the POPular Age Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(10):3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103249

Chicago/Turabian StyleGimbel, Marieke E., Anne H. Tavenier, Wilbert Bor, Renicus S. Hermanides, Evelyn de Vrey, Ton Heestermans, Melvyn Tjon Joe Gin, Reinier Waalewijn, Sjoerd Hofma, Frank den Hartog, and et al. 2020. "Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel in Older Patients with NSTE-ACS Using Oral Anticoagulation: A Sub-Analysis of the POPular Age Trial" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 10: 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103249

APA StyleGimbel, M. E., Tavenier, A. H., Bor, W., Hermanides, R. S., de Vrey, E., Heestermans, T., Gin, M. T. J., Waalewijn, R., Hofma, S., den Hartog, F., Jukema, W., von Birgelen, C., Voskuil, M., Kelder, J., Deneer, V., & ten Berg, J. M. (2020). Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel in Older Patients with NSTE-ACS Using Oral Anticoagulation: A Sub-Analysis of the POPular Age Trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(10), 3249. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103249