1. Introduction

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, regardless of gender or ethnicity. In terms of morbidity, lung cancer ranks second in men and in women in the United States [

1]. In the European Union, lung cancer causes approximately 270,000 deaths per year [

2,

3]. Poland is among the countries with the highest morbidity and mortality from lung cancer [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Lung cancer has a very poor prognosis. Primary prevention (i.e., reducing or ceasing smoking and avoiding passive smoking) is thought to be the only effective approach. Lung cancer is often clinically silent when confined to the lung parenchyma, and it causes non-specific symptoms when growing in the bronchi. A reported 30–57% of patients have distant metastases at the time of diagnosis [

2,

8].

Computed tomography (CT) provides sufficient resolution to detect small lung nodules. Low-dose non-contrast CT has gained interest as a screening tool for early lung cancer detection while minimizing radiation exposure. Early diagnosis increases resectability and eligibility for curative surgery, which remains the most effective treatment for non-small cell lung cancer but is limited to early-stage disease. Lung cancer has low resection rates (16–20% in Poland [

9,

10] and ~30% in countries with more advanced health care systems [

7]), largely due to late diagnosis [

11]. It also has one of the lowest 5-year survival rates among malignancies (14–18%) [

4,

8]. Five-year survival reaches approximately 67% in stage I disease but drops to 23% in stage III [

12]. Only 15–25% of cases are diagnosed at a stage suitable for radical surgery [

13], while over 60% are detected at advanced stages [

14,

15]. Early detection can increase 5-year survival to over 50% [

2].

In 2011, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) reported for the first time a significant decrease (20%) in lung cancer mortality among a group of patients undergoing screening by LDCT compared to a group of patients diagnosed using chest X-ray [

16,

17]. Among patients operated on for stage I lung cancer, 93% remained relapse-free for 5 years. In 2016, the NELSON study (Dutch-Belgian Randomized Lung Cancer Screening Trial) conducted in the Netherlands and Belgium showed a significant decrease in lung cancer mortality (26% in men and 39–61% in women) among patients screened by LDCT compared with patients who were not screened [

3,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Although the research data may seem promising in terms of reducing mortality, questions remain regarding the implementation of universal screening for high-risk individuals, primarily regarding cost-effectiveness and overtreatment.

Lung cancer screening programs worldwide vary in their inclusion criteria, including age, tobacco exposure, environmental or occupational exposure, chronic respiratory disease, and family history of lung cancer. Smoking remains the dominant eligibility criterion in most programs [

24], as the most significant risk factor. Data shows that 1 in 10 smokers develops lung cancer an average of 30 to 40 years after they start smoking [

25]. Some authors have stated that screening programs for early lung cancer detection prove to be more effective when combined with a program supporting smoking cessation [

26,

27]. The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends annual screening for adults aged 50 to 80 years with a history of at least 20 pack-years of cigarette smoking. Former smokers must have quit smoking within the past 15 years to be eligible [

28].

A study from Greece suggested that implementing an LDCT screening strategy covering 100% of high-risk adults aged 50–80 years would avoid additional deaths and increase the lung cancer life years (LCLY) over 5 years [

3]. Similar conclusions were drawn in studies in Japan [

8]. The Lithuanian screening program examined individuals aged 50 to 70 years. This program was unique in that it included individuals regardless of smoking status. The results of this study also indicated that diseases would be detected before they become clinically apparent in many individuals through a single, non-invasive, periodic examination. Furthermore, disease detection strongly motivates patients to change harmful habits and take preventive measures [

2]. Another study [

29] involved elderly participants (aged ≥ 70 years), a population that often fails to meet the stringent inclusion criteria of clinical trials. The findings indicated that early detection and timely initiation of appropriate therapy are achievable in this group, with nearly half of the patients undergoing radical surgery at an early stage of the disease.

This study analyzed the surgical aspects of non-small cell lung cancer detected through a low-dose CT–based screening program in Szczecin, the first program of its kind in Poland. The aim was to evaluate the impact of introducing LDCT screening on the surgical management of non-small cell lung cancer and on the functioning of a thoracic surgery department. The analysis included patient and lesion characteristics identified through the program, as well as perioperative care and organizational aspects related to hospitalization.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of the Study Groups in Sex and Age

The patients were divided into three groups: Group 1a included 52 surgically treated lung cancer patients participating in the diagnosis program; Group 1b included 87 patients surgically treated for lung cancer outside the program but during the same period; and Group 2 was the control group of 103 lung cancer patients treated surgically in the period prior to the program’s implementation. The sex and age distributions of the groups are given in

Table 1.

3.2. Comparison of the Study Groups Regarding Smoking

Smoking was considered one of the most important risk factors for lung cancer. All patients in Group 1a were cigarette smokers, as smoking was a factor for inclusion in the screening study. In Group 1b, 74 individuals (85.1%) were smokers, and 91 individuals (88.3%) in Group 2 were smokers. No significant relationship was found among groups.

3.3. Distribution of Cancer Locations in Each Group

The location of primary lung cancer in each group is illustrated in the table below (

Table 2).

3.4. Histopathological Types

Figure 1 illustrates the types of primary lung cancer based on the histological diagnosis. Adenocarcinoma had a significantly higher occurrence rate in Group 1a than in Group 1b (

p = 0.012) and Group 2 (

p = 0.0297). No significant difference in the occurrence rate of adenocarcinoma was found between Groups 1b and 2 (

p = 0.740). Comparing the occurrence rates of squamous cell carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma, and carcinoid, no significant relationship was found between Groups 1a and 1b or between Groups 1a and 2. However, when comparing groups 1b and 2, a statistically significant difference was found in the incidence of large cell carcinoma (

p = 0.01).

3.5. Grading of the Primary Lung Cancer

The distribution of lung cancer grades in each group is shown in

Table 3. A significant difference in the occurrence rates of grades G2 and G3 was found in Group 1a (

p < 0.001), with G2 occurring more frequently. However, the differences in the occurrence rates of G1 and G2 or G1 and G3 were not significant. No significant differences in grades were found in Groups 1b and 2.

Comparing occurrence rates between Groups 1a and 1b, the differences were not significant. We also found no significant differences when comparing Groups 1b and 2. In contrast, we found a significant difference in grade G2 occurrence between Groups 1a and 2, as it occurred significantly more frequently in Group 1a (p = 0.02). However, the difference in the occurrence of G1 and G3 was not significant between these two groups.

3.6. Lung Cancer Staging

The TNM VII classification for each group is given in

Table 4. Comparing Group 1a to Groups 1b and 2, only the T1a feature, carcinoma of the lowest stage, was significantly different (

p = 0.002 and

p = 0.001, respectively). This difference was not found between Groups 1b and 2.

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 present the comparison among groups. Regarding clinical stages (IA-IV based on the TNM VII classification—

Table 8), IA occurred significantly more frequently in Group 1a than in Group 1b (

p = 0.03) and Group 2 (

p = 0.025), whereas IIIA occurred significantly more frequently in Group 1b than in Group 2 (

p = 0.03).

3.7. Other Studied Factors

Tumor volume was measured in cubic centimeters (cm

3) and was significantly smaller in Group 1a than in Group 2 (

p = 0.01) and Group 1b (

p = 0.004), as well as both Groups 1b and 2 combined (

p = 0.003)—

Table 9. No significant difference was found in tumor volume between Groups 1b and 2 (

p = 0.53).

The waiting time for surgery was significantly different between Groups 1a and 2 (p = 0.0134), but not between Groups 1a and 1b (p = 0.39) or Groups 1b and 2 (p = 0.08).

A significant difference in the mean procedure duration was found between Groups 1a and 1b (p = 0.02) and Groups 1a and 2 (p = 0.007). The average procedure duration was longer in Group 1a than in the other groups, but we did not find a significant difference in the average durations of procedures in Groups 1b and 2. The duration of surgery in patients with complications (n = 48 patients) and without complications did not differ significantly (p = 0.79).

Groups 1a and 1b had significantly shorter duration of hospitalization than Group 2, but no significant difference was found between Groups 1a and 1b. Therefore, the duration of hospitalization was significantly shorter during the screening program than in the period before the program was implemented. However, during the period of the early lung cancer detection program, there was no significant difference between patients who did and did not participate in the program.

3.8. Invasive Procedure-Based Diagnosis

The number of patients diagnosed via an invasive procedure is provided in

Table 10.

No significant difference was found among the groups. However, a diagnosis was not made based on invasive procedures approximately 1.6-times more often in Group 1a.

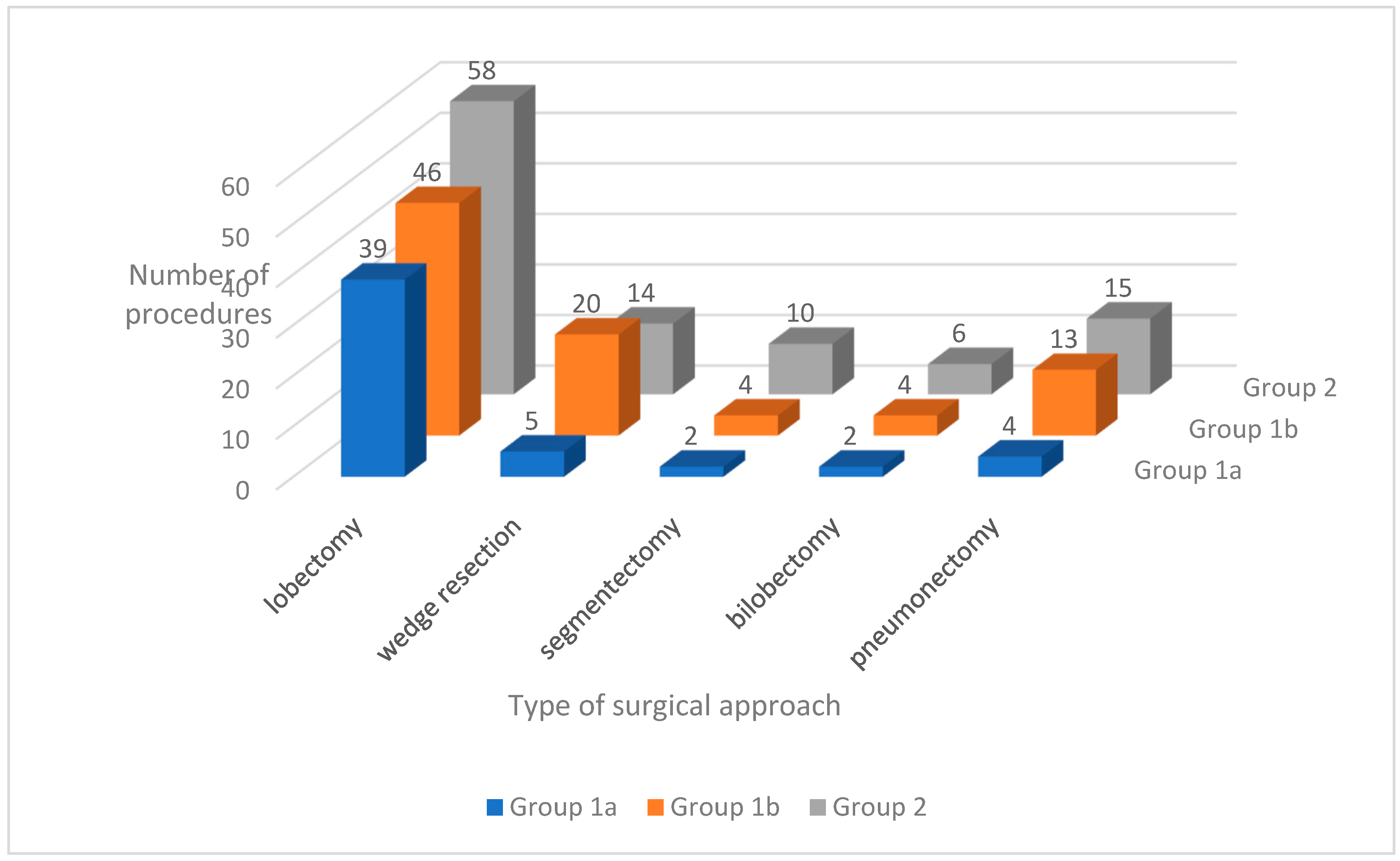

3.9. Types and Numbers of Performed Procedures

The distribution of surgical approaches used in each group is shown in

Figure 2. A comparison of the procedures performed is provided in

Table 11.

Of all the procedures, only lobectomy with mediastinal lymphadenectomy was significantly more frequent in Group 1a than in Groups 1b and 2.

Significantly more surgeries due to primary lung cancer were performed (p < 0.05) during the period of the screening program compared with the period before the program.

3.10. Perioperative and Postoperative Complications

We found no significant difference in the occurrence of such perioperative complications between Groups 1a and 1b (p = 0.25), Groups 1a and 2 (p = 0.12), or Groups 1b and 2 (p = 0.80). We also found no significant differences in the frequency of perioperative deaths between Groups 1a and 2 (p = 0.53), Groups 1a and 1b (p = 0.71), or Groups 1b and 2 (p = 0.85).

In Group 1a, a late postoperative complication occurred in 1 (1.9%) patient in the form of chronic emphysematous space. In Group 1b, no late postoperative complication occurred. In Group 2, a late postoperative complication occurred in 4 (3.9%) patients: wound dehiscence with subcutaneous hematoma that required reoperation, acute respiratory failure and circulatory failure, wound dehiscence and empyema of the right pleural cavity, and empyema requiring the Weder method.

No significant relationships were found among the groups for the frequency and grading (Group 1a, p ≥ 0.32; Group 1b, p ≥ 0.36; Group 2, p ≥ 0.47) and co-morbidities (Group 1a, p = 0.75; Group 1b, p = 0.23; Group 2, p = 0.39). The duration of the procedure in the case of complications and without perioperative complications did not differ statistically significantly (p = 0.79).

However, a significant correlation was found between the need for blood transfusion and the occurrence of perioperative complications (all studied groups, p = 0.0002; Group 1b, p = 0.01; Group 2, p = 0.04). Of those patients who received transfusions, 39.3% experienced perioperative complications. Among those who did not require transfusions, 14.7% experienced perioperative complications. However, for Group 1a, this correlation was not significant (p = 0.6).

4. Discussion

The results of our study are consistent with large, randomized trials; our work provides additional important information. The literature on lung cancer screening seldom discusses the surgical and organizational issues encountered during the treatment of patients diagnosed over the course of these screenings [

4,

9].

Among the patients screened at our clinic, adenocarcinoma occurred significantly more frequently than in the other study groups. A CT of the thorax visualizes peripheral structures of the lungs, where adenocarcinoma is most frequently located, better than the central structures [

30,

31]. In central lung regions near the hilum, tumors may mimic vascular structures or lymphadenopathy. Squamous cell carcinomas typically occur centrally, whereas adenocarcinomas are more often peripheral. Thus, CT imaging is more effective in diagnosing peripheral lung lesions, and screening with LDCT tends to detect predominantly peripheral tumors, as observed in the LUSI trial and the American NLST [

32,

33].

Tumor size/volume is conceptually related to prognosis and is reflected in the T stage of the TNM system. The tumor volume is also an independent and important prognostic factor for 5-year survival. It provides a continuous and more detailed measure than categorical T staging, which may offer additional prognostic value. Patients diagnosed during the screening had significantly smaller neoplasms. For adenocarcinoma of the lung with a diameter of 10 mm measured on CT, the 5-year survival is estimated to be 97.9%, whereas estimates are 68.1% for diameters of 10–20 mm, 53.7% for diameters of 20–30 mm, and only 15.7% for diameters > 30 mm [

34]. Tumor volume measurement in LDCT improves individual clinical decision-making. Automated volumetric nodule classification enhances assessment of growth dynamics (stable vs. growing), reduces radiologists’ workload, and has been shown to decrease false-negative classifications when AI is used as a standalone CT reader [

35].

The significant differences in TNM VII clinical stage classification were similarly reported by other studies [

34,

36,

37]. Invasive procedures (bronchofiberoscopy, Endobronchial Ultrasonography (EBUS), Endoscopic Ultrasonography (EUS), biopsy, and mediastinoscopy) were performed to confirm staging or diagnose indeterminate CT findings [

38,

39]; 42–77% of the NELSON program patients underwent invasive procedures to determine the lung cancer grade [

40]. The current aim is to limit the number of invasive procedures in the patient population undergoing screenings for early lung cancer diagnosis [

41,

42,

43].

The difference in the waiting time for surgery (from admission for surgery to the day of surgery) was significantly shorter in the screened population than in the period before screening, but we did not find a difference between the screened population and the patients who did not undergo screening during the same time period. In two studies that did not screen patients, one determined the waiting time to be 25 days, and the other reported 5 weeks [

44,

45].

We found a significant increase in the frequency of surgeries due to primary lung cancer (for all extents of pulmonary parenchyma resection) during the LDCT-based screening program compared with the period prior to the program’s introduction. The extent of the operation depended mostly on the cancer stage [

46]. During the screening program, it seemed that the information from the LDCT pilot study would help identify a larger group of patients with primary lung cancer treated with traditional open lobectomy with mediastinal lymphadenectomy, which was the commonly used resection method those days. The experience accumulated over the following years enabled not only the implementation of LDCT screening but also the routine adoption of videothoracoscopic techniques, the broad application of anatomical sublobar resections, the use of combined CT and PET-CT imaging, the evaluation of EGFR mutations and PD-L1 expression, and the advancement of liquid biopsy technology. During the program of our study, the number of lobectomies with mediastinal lymphadenectomy was significantly greater in the screened population, whereas the number of pneumonectomies was roughly 50% lower in this group than in the other groups. In the Danish screening study, lobectomy was the most common procedure [

47]. In the treatment of low-stage non-small cell lung cancer, lobectomy with mediastinal lymphadenectomy fulfills the definition of radical oncological resection. Performing resections more limited than lobectomy remains controversial [

48]. A different opinion was presented by Hennon and Yendamuri, who stated that segmentectomy is sufficient for the radical resection of peripheral T1 masses with a diameter < 2 cm [

49].

Surgeries were significantly longer in the screened population than in the other groups. In this group, 75% of the surgeries were lobectomies and, in some cases, an intraoperative examination was performed. Dominioni et al. reported an average operation time of 180 min in lung cancer patients, whereas the Danish screening study stated an average of 135 min (VATS) [

47,

50]. We did not find a correlation between the duration of the operation and the occurrence of perioperative complications, which contradicts the positive correlation reported by Shiono et al. [

51].

Blood transfusions are considered an independent risk factor for perioperative complications and mortality. We confirmed a correlation between the number of transfused units and the occurrence of perioperative complications. Little et al. [

52] reported that 13.7% of patients received blood transfusions and demonstrated a correlation between blood transfusion and an increase in perioperative complications and mortality. Thomas et al. showed that blood transfusion affected the mortality rate among pneumonectomy patients. They determined the factors causing the increased demand for blood transfusions, which affected 16–25% of patients [

53]. Blood transfusions increase the frequency of infectious and respiratory complications due to transfusion-related acute lung injury [

54].

The hospitalization time was significantly shorter during the period of screening than during the time period prior. Gargarine et al. reported an average duration of hospitalization of 7.3 days for patients undergoing lobectomy due to neoplasm and non-neoplasm-related reasons [

55]. Alarcon et al. hospitalized their patients for 3.4 to 9.8 days on average and proposed a “Fast-Track Surgery” protocol to shorten it [

48]. Shiono et al.’s patients were hospitalized for 13 days on average [

51].

The screened population did not have any perioperative deaths, but the perioperative mortality reached 2.3% in the non-screened population operated on during the same time period, and was 2.9% prior to the screening period. The perioperative mortality (within 30 days from operation) rate among Little et al.’s patients was 5.2% after lobectomy, 8.5% after pneumonectomy, and 4.9% after peripheral resection [

52]. Gagarine et al. reported a mortality rate of 2.2% for their lobectomy patients [

55].

The screened population had the fewest number of complications. In addition, we identified a significant relationship between perioperative complications and blood product transfusions in the non-screened population and the time period before screening.

Beyond standard screening outcomes such as early detection, grading, and staging, this study focused on surgical aspects, including length of hospitalization and postoperative complications. Evaluating the screening program from a thoracic surgery perspective allowed assessment of its impact on departmental workflow and resource demands, with implications for clinical and economic planning. Previous studies have largely emphasized screening limitations, including high false-positive rates and indeterminate nodules, leading to additional diagnostic procedures, increased radiation exposure, misdiagnosis, which cause an overtreatment, exposing patients to unnecessary surgical procedures and patient anxiety. It is important to emphasize that, currently, routine preoperative evaluation of lung cancer should include additional computed tomography (CT). The purpose of this examination is to identify small metastases, lymph node involvement, and assess for involvement of other tissues and organs. Additionally, the lungs can be assessed to detect the presence or absence of comorbidities (emphysema, fibrosis, interstitial lung disease) and to examine anatomical variations in the bronchial vascular system [

56]. Increasing screening specificity through automated nodule volume assessment and biomarkers can improve nodule identification [

35]. Recent advances in biomarker research suitable for mass screening include proteins, miRNAs, circulating tumor cells, and tumor DNA [

12]. As LDCT screening enables detection of early-stage disease, improved lung cancer risk models are increasingly valuable for patient selection [

57,

58]. Emerging approaches combined with LDCT aim to detect early malignancy, stratify risk, distinguish benign from malignant nodules, and predict treatment response, using blood-based biomarkers (cfDNA, methylation patterns, CYFRA 21-1, CRP), non-blood biomarkers (exhaled air compounds, sputum cells), and miRNAs to reduce the need for invasive testing [

12,

21,

22,

59].

Intensive work is currently underway on systems that assist in the interpretation of CT scans. Technological advances could take LDCT screening to a new level by automating the identification of nodules and reducing the number of false positives. Specialists are developing technological solutions, such as deep learning-based image reconstruction algorithms and artificial intelligence tools, to improve the quality of radiological images and help physicians cope with the increasing workload resulting from more CT scans by screening programs. Radiomics is based on the extraction of a large number of medical image features that support the identification of cancer-specific features using data characterization algorithms, and the use of numerous computer-aided diagnostic systems has led to the development of methods for faster and more accurate detection of lung nodules [

35]. Improved methods for evaluating CT images have also been developed to minimize the risk of misinterpreting small changes in the lungs. In nodule detection, methods based on convolutional neural networks (CNN) are characterized by higher detection sensitivity and can be continuously improved and optimized based on LDCT scans [

60,

61,

62]. The use of artificial intelligence for lung nodule detection has proven to be an effective and valuable tool in lung cancer screening, greatly supporting the diagnostic process, but current data indicate that a high rate of true negative diagnoses may still be a problem [

63].

A limitation of this study is its pilot character and the restricted study population, as the screening was conducted in 2008 and included only residents of Szczecin. Strict inclusion criteria further limited the scope of analysis and precluded broader conclusions, such as those concerning age at first diagnosis. At the time of the study, limited access to diagnostic tools and procedures influenced both screening and surgical practices. Moreover, the analyzed medical records did not allow assessment of the financial aspects of implementing the screening program. These limitations indicate the need for further development of LDCT-based screening programs, involving larger and more diverse populations, and for analysis of outcomes using current diagnostic and therapeutic standards in lung cancer.