Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid Profile and Lipid-Related Diseases: A Large Community-Based Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

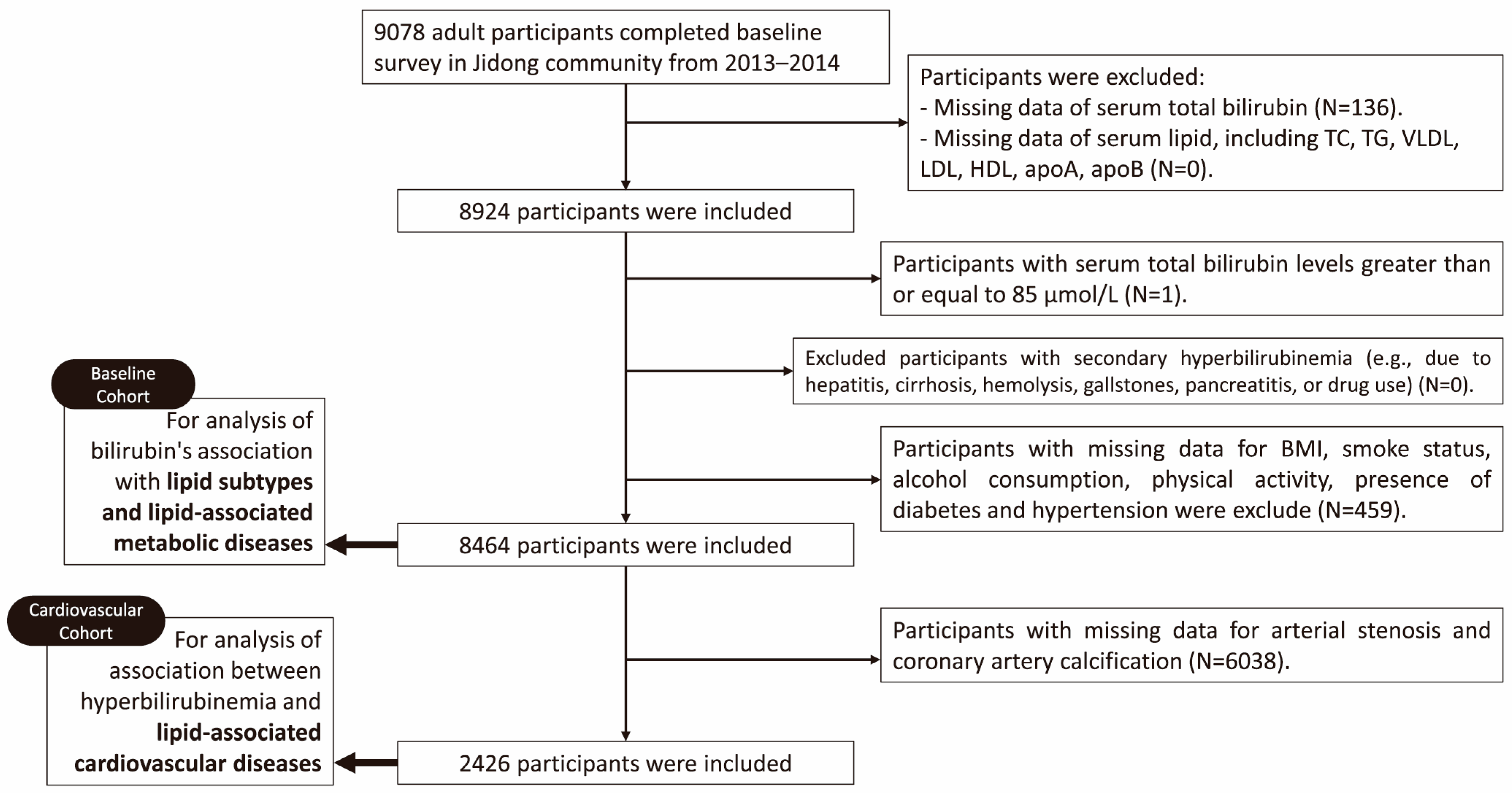

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Definition of Hyperbilirubinemia and Hyperlipidemia

2.3. Covariates and Data Collection

2.4. Definition of Lipid-Related Diseases

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid Subclasses

3.1.1. Baseline Characteristics of Our Baseline Cohort

3.1.2. Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Hyperlipidemia

3.1.3. Logistic Regression Analysis of Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid Subclasses

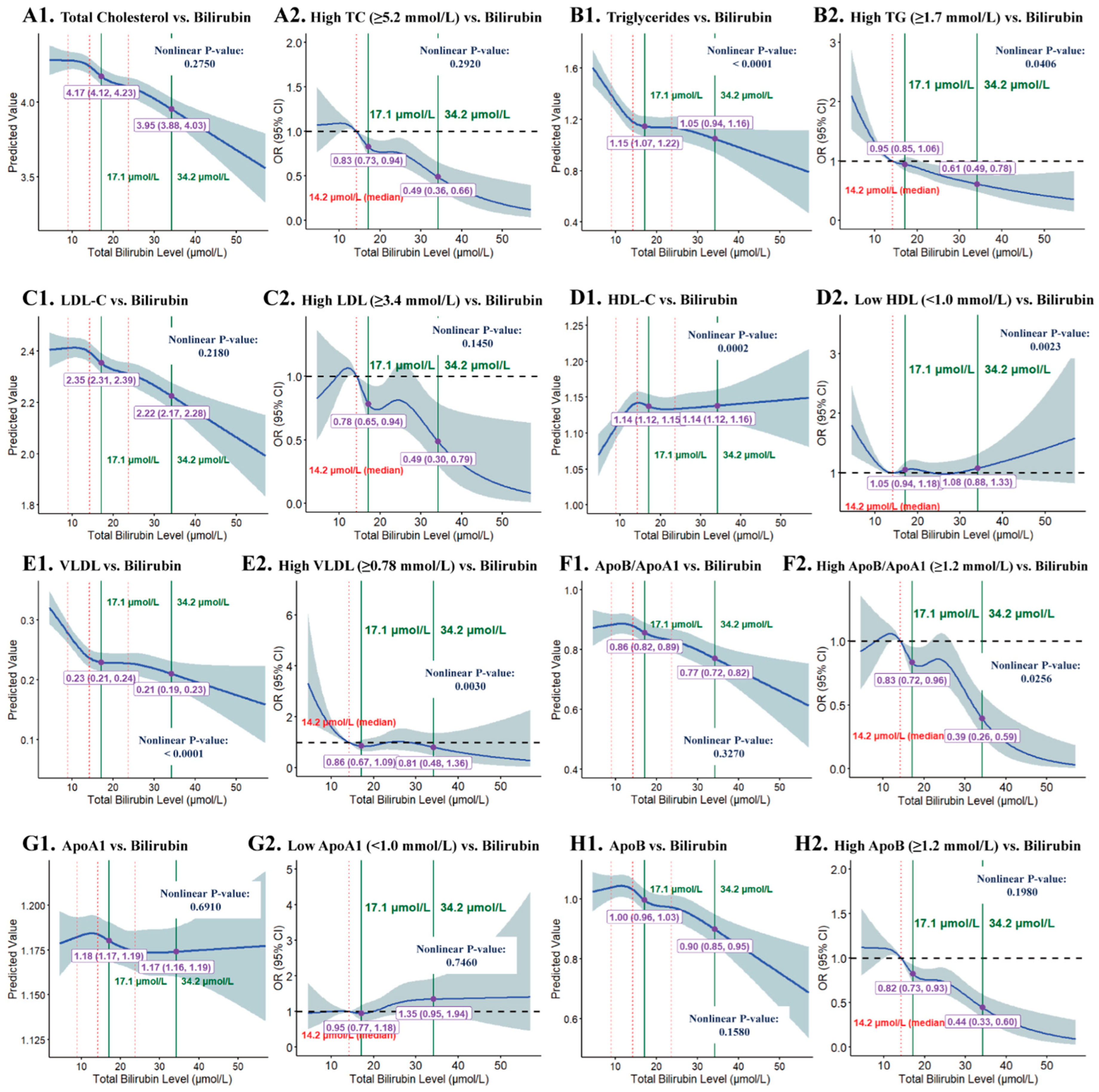

3.1.4. RCS Analysis of STB Levels and Lipid Subclasses

3.2. Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid-Related Diseases

3.2.1. Baseline Characteristics of Our Cardiovascular Cohort

3.2.2. Logistic Regression Analysis of Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid-Related Diseases

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.2. Observations and Possible Interpretations

4.3. Potential Mechanisms

4.4. Implications and Future Directions

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STB | Serum total bilirubin |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| VLDL | Very low-density lipoprotein |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CAC | Coronary artery calcification |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

References

- Stocker, R.; Yamamoto, Y.; McDonagh, A.F.; Glazer, A.N.; Ames, B.N. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science 1987, 235, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Qi, X.; Vitek, L.; Arrese, M. Evaluating an outpatient with an elevated bilirubin. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol.|ACG 2019, 114, 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítek, L. Bilirubin as a signaling molecule. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 1335–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Kim, D.H.; Hwang, J.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, J.H.; Lim, C.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, J.P. Elevated bilirubin levels are associated with a better renal prognosis and ameliorate kidney fibrosis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, H.J.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, T.W.; Na, K.Y.; Oh, K.H.; Joo, K.W.; Yoon, H.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Ahn, C.; Han, J.S.; et al. The mildly elevated serum bilirubin level is negatively associated with the incidence of end stage renal disease in patients with IgA nephropathy. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2009, 24, S22–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Liu, C.; Lai, F.; Dong, S.; Chen, H.; Chen, L.; Shi, L.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, C.; Lv, X.; et al. Associations between serum total bilirubin, obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Jiang, X.; Kou, L.; Samuriwo, A.T.; Xu, H.L.; Zhao, Y.Z. Pharmacological actions and therapeutic potentials of bilirubin in islet transplantation for the treatment of diabetes. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 145, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.F.; Bordoni, B. Hyperlipidemia; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Libby, P.; Buring, J.E.; Badimon, L.; Hansson, G.K.; Deanfield, J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Lewis, E.F. Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, G.K.; Miller, J.P.; Heagerty, A.M. Hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, and coronary heart disease. Lancet 1995, 345, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, R.; Ninomiya, D.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kasai, Y.; Kusunoki, T.; Ohtsuka, N.; Kumagi, T.; Abe, M. Mildly elevated serum bilirubin levels are negatively associated with carotid atherosclerosis among elderly persons. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítek, L. Bilirubin and atherosclerotic diseases. Physiol. Res. 2017, 66, S11–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed Khoei, N.; Wagner, K.H.; Sedlmeier, A.M.; Gunter, M.J.; Murphy, N.; Freisling, H. Bilirubin as an indicator of cardiometabolic health: A cross-sectional analysis in the UK Biobank. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.; Cho, Y.R.; Park, M.K.; Kim, D.K.; Cho, N.H.; Lee, M.K. Relationship between serum bilirubin levels and cardiovascular disease. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, R.; Ninomiya, D.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kasai, Y.; Kusunoki, T.; Ohtsuka, N.; Kumagi, T.; Abe, M. Mildly elevated serum total bilirubin levels are negatively associated with carotid atherosclerosis among elderly persons with type 2 diabetes. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2016, 38, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, E. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between serum bilirubin and dyslipidemia in a health screening population. Atherosclerosis 2015, 239, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Meng, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, M.; Ren, X.; Zhu, M.; He, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Song, K.; Jia, Q.; et al. The association between total bilirubin and serum triglyceride in both sexes in Chinese. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, B.A.; Durstine, J.L.; Roberts, C.K.; Barnard, R.J. Impact of diet and exercise on lipid management in the modern era. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 28, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momayyezi, M.; Jambarsang, S.; Fallahzadeh, H.; Sefidkar, R. Association between lipid profiles and cigarette smoke among adults in the Persian cohort (Shahedieh) study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Imaoka, W.; Kuroshima, T.; Toragai, R.; Ito, Y.; Kanda, E.; Schaefer, J.S.; Ai, M. Relationships between Smoking Status, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and Lipoproteins in a Large Japanese Population. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2021, 28, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, S.P.; Liu, X.H.; Du, X.; Kang, J.P.; Lü, Q.; Dong, J.Z.; Gu, C.X.; Huang, F.J.; Zhou, Y.J.; Li, Z.Z.; et al. Profile of risk factors modification after coronary revascularization in patients with coronary artery disease. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2006, 86, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Žiberna, L.; Jenko-Pražnikar, Z.; Petelin, A. Serum Bilirubin Levels in Overweight and Obese Individuals: The Importance of Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Responses. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenko-Pražnikar, Z.; Petelin, A.; Jurdana, M.; Žiberna, L. Serum bilirubin levels are lower in overweight asymptomatic middle-aged adults: An early indicator of metabolic syndrome? Metabolism 2013, 62, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, C.; Weeke, P.; Fosbøl, E.L.; Brendorp, B.; Køber, L.; Coutinho, W.; Sharma, A.M.; Van Gaal, L.; Finer, N.; James, W.P.; et al. Acute effect of weight loss on levels of total bilirubin in obese, cardiovascular high-risk patients: An analysis from the lead-in period of the Sibutramine Cardiovascular Outcome trial. Metabolism 2009, 58, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Bautista, L.E. Serum bilirubin and the risk of hypertension. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortada, I. Hyperbilirubinemia, Hypertension, and CKD: The Links. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2017, 19, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, B.; Lin, Y.; Lin, S.; Chen, T.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, L.; et al. The association between bilirubin and hypertension among a Chinese ageing cohort: A prospective follow-up study. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Tumanov, S.; Stanley, C.P.; Kong, S.M.Y.; Nadel, J.; Vigder, N.; Newington, D.L.; Wang, X.S.; Dunn, L.L.; Stocker, R. Destabilization of Atherosclerotic Plaque by Bilirubin Deficiency. Circ. Res. 2023, 132, 812–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Fukui, M.; Tomiyasu, K.; Akabame, S.; Nakano, K.; Hasegawa, G.; Oda, Y.; Nakamura, N. Low serum bilirubin concentration is associated with coronary artery calcification (CAC). Atherosclerosis 2009, 206, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.J.; Kim, D.; Park, H.E.; Chung, G.E.; Choi, S.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, W.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, S.H. Elevated serum bilirubin levels are inversely associated with coronary artery atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2013, 230, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.J.; Kim, S.H. Inverse relationship between fasting direct bilirubin and metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Clin. Chim. Acta 2010, 411, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Yun, K.E.; Choi, H.J. Relationships between serum total bilirubin levels and metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Ni, C.; Chang, B.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Li, B. Association between serum total bilirubin levels and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 152, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, M.S.; Kim, D.; Chung, G.E.; Kang, S.J.; Park, M.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, H.S. Serum bilirubin levels are inversely associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2012, 18, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellarosa, C.; Bedogni, G.; Bianco, A.; Cicolini, S.; Caroli, D.; Tiribelli, C.; Sartorio, A. Association of Serum Bilirubin Level with Metabolic Syndrome and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study of 1672 Obese Children. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhong, R.; Liu, C.; Tang, Y.; Gong, J.; Chang, J.; Lou, J.; Ke, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Association between bilirubin and risk of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease based on a prospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Frysz, M.; Verweij, N.; Kieneker, L.M.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Dullaart, R.P.F. Circulating total bilirubin and risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the PREVEND study: Observational findings and a Mendelian randomization study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; An, P.; Jia, X.; Yue, X.; Zheng, S.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; An, W.; Winkler, C.A.; Duan, Z. Genetically Regulated Bilirubin and Risk of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, Y. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: New nomenclature and approach with hot debate. World J. Hepatol. 2023, 15, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, Y.; Kang, M.W.; Kim, K.; Kim, Y.C.; Han, S.S.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.P.; et al. Serum bilirubin and kidney function: A Mendelian randomization study. Clin. Kidney J. 2022, 15, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.T.; Tarng, D.C. Beyond a Measure of Liver Function-Bilirubin Acts as a Potential Cardiovascular Protector in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 20, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.Q.; Santos, C.D.; Rubin, D.I.; Siegel, J.L.; Freeman, W.D. Guillain-Barré Syndrome After Acute Hepatitis E Infection: A Case Report and Literature Review. Crit. Care Nurse 2021, 41, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, N.; Kaur, P.; Garg, P.; Ranjan, V.; Ralmilay, S.; Rathi, S.; De, A.; Premkumar, M.; Taneja, S.; Roy, A.; et al. Clinical and pathophysiological characteristics of non-acute decompensation of cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plagiannakos, C.G.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Lytvyak, E.; Roberts, S.B.; Ismail, M.; Gulamhusein, A.F.; Selzner, N.; Qumosani, K.M.; Worobetz, L.; Hercun, J.; et al. Treatment response and clinical event-free survival in autoimmune hepatitis: A Canadian multicentre cohort study. J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brain, M.C.; Bull, B.S.; Dacie, J.V.; Regoeczi, E.; Rubenberg, M.L. Microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia. Lancet 1968, 291, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.J.; Gao, C.F.; Wei, D.; Wang, C.; Ding, S.Q. Acute pancreatitis: Etiology and common pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, J.I.; Rockey, D.C. Diagnosis and evaluation of hyperbilirubinemia. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 33, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Hawken, S.; Ounpuu, S.; Dans, T.; Avezum, A.; Lanas, F.; McQueen, M.; Budaj, A.; Pais, P.; Varigos, J.; et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004, 364, 937–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Xu, X.; You, H.; Ge, J.; Wu, Q. Healthcare costs attributable to abnormal weight in China: Evidence based on a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, E.K.; Strouse, R.; Hall, J.; Kovac, M.; Schroeder, S.A. National survey of U.S. health professionals’ smoking prevalence, cessation practices, and beliefs. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010, 12, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Fukui, S.; Shinozaki, T.; Asano, T.; Yoshida, T.; Aoki, J.; Mizuno, A. Lipid Profiles After Changes in Alcohol Consumption Among Adults Undergoing Annual Checkups. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e250583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. In WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018, 71, e13–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, S15–S33. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, H.J.; Taylor, D.W.; Eliasziw, M.; Fox, A.J.; Ferguson, G.G.; Haynes, R.B.; Rankin, R.N.; Clagett, G.P.; Hachinski, V.C.; Sackett, D.L.; et al. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1415–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, I.S.; Termeie, O.G.; Kristo, S.; Schroeder, L.P.; Lakshmanan, S.; Shafter, A.M.; Hussein, L.; Verghese, D.; Aldana-Bitar, J.; Manubolu, V.S.; et al. Major Global Coronary Artery Calcium Guidelines. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazhar, S.M.; Shiehmorteza, M.; Sirlin, C.B. Noninvasive assessment of hepatic steatosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Xu, S.; Jia, A.; Cai, J.; Zhao, M.; Guo, J.; Ji, Q.; Ming, J. Recommendations for revision of Chinese diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome: A nationwide study. J. Diabetes 2018, 10, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, V.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Iseki, K.; Li, Z.; Naicker, S.; Plattner, B.; Saran, R.; Wang, A.Y.; Yang, C.W. Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013, 382, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inker, L.A.; Eneanya, N.D.; Coresh, J.; Tighiouart, H.; Wang, D.; Sang, Y.; Crews, D.C.; Doria, A.; Estrella, M.M.; Froissart, M.; et al. New Creatinine- and Cystatin C-Based Equations to Estimate GFR without Race. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Li, H.; Si, S.; Yu, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Yan, R.; Yu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, F.; et al. Exploring the causal pathway from bilirubin to CVD and diabetes in the UK biobank cohort study: Observational findings and Mendelian randomization studies. Atherosclerosis 2021, 320, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, G. Serum Bilirubin Level Is Increased in Metabolically Healthy Obesity. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 792795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Qiao, J.; Zhang, H. Mildly elevated serum bilirubin and its correlations with lipid levels among male patients undergoing health checkups. Lipids Health Dis. 2023, 22, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed Khoei, N.; Grindel, A.; Wallner, M.; Mölzer, C.; Doberer, D.; Marculescu, R.; Bulmer, A.; Wagner, K.H. Mild hyperbilirubinaemia as an endogenous mitigator of overweight and obesity: Implications for improved metabolic health. Atherosclerosis 2018, 269, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, D.; Wang, X.L. Smoking, oxidative stress and cardiovascular diseases--do anti-oxidative therapies fail? Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado, A.; Domingo, E.; Piqueras, L.; Sanz, M.-J. Primary hypercholesterolemia and development of cardiovascular disorders: Cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in low-grade systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 139, 106066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundur, A.R.; Singh, I.; Bulmer, A.C. Bilirubin, platelet activation and heart disease: A missing link to cardiovascular protection in Gilbert′s syndrome? Atherosclerosis 2015, 239, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gul, M.; Kalkan, A.K.; Uyarel, H. Serum bilirubin: A friendly or an enemy against cardiovascular diseases? J. Crit. Care 2014, 29, 305–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, R. Antioxidant activities of bile pigments. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2004, 6, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minetti, M.; Mallozzi, C.; Di Stasi, A.M.; Pietraforte, D. Bilirubin is an effective antioxidant of peroxynitrite-mediated protein oxidation in human blood plasma. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 352, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranano, D.E.; Rao, M.; Ferris, C.D.; Snyder, S.H. Biliverdin reductase: A major physiologic cytoprotectant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 16093–16098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlak, T.W.; Saleh, M.; Higginson, D.S.; Paul, B.D.; Juluri, K.R.; Snyder, S.H. Bilirubin and glutathione have complementary antioxidant and cytoprotective roles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5171–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-W.; Fung, K.-P.; Yang, C.-C. Unconjugated bilirubin inhibits the oxidation of human low density lipoprotein better than Trolox. Life Sci. 1994, 54, PL477–PL481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.T.; DelCimmuto, N.R.; Flack, K.D.; Stec, D.E.; Hinds, T.D., Jr. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Antioxidants as Immunomodulators in Exercise: Implications for Heme Oxygenase and Bilirubin. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersten, S.; Stienstra, R. The role and regulation of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha in human liver. Biochimie 2017, 136, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, D.M.; Blomquist, T.M.; Miruzzi, S.A.; McCullumsmith, R.; Stec, D.E.; Hinds, T.D. RNA sequencing in human HepG2 hepatocytes reveals PPAR-α mediates transcriptome responsiveness of bilirubin. Physiol. Genom. 2019, 51, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Total | Nonhyperbilirubinemia | Hyperbilirubinemia | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 8464 | n = 5792 | n = 2672 | |||

| Age (years, median [Q1, Q3]) | 41 [31, 52] | 41 [31, 52] | 41 [31, 53] | 0.6800 | |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Male | 4382 (51.77) | 2534 (43.75) | 1848 (69.16) | ||

| Female | 4082 (48.23) | 3258 (56.25) | 824 (30.84) | ||

| Physical Activity, n (%) | 0.0826 | ||||

| Inactive | 2704 (31.95) | 1893 (32.68) | 811 (30.35) | ||

| Occasional | 1158 (13.68) | 793 (13.69) | 365 (13.66) | ||

| Frequently | 4602 (54.37) | 3106 (53.63) | 1496 (55.99) | ||

| Alcohol Consumption, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Never | 5658 (66.85) | 4120 (71.13) | 1538 (57.56) | ||

| <1 standard drink | 1255 (14.83) | 740 (12.78) | 515 (19.27) | ||

| ≥1 standard drink | 1551 (18.32) | 923 (16.09) | 619 (23.17) | ||

| Smoke Status, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| Never | 5983 (70.69) | 4247 (73.33) | 1736 (64.97) | ||

| Current | 2159 (25.51) | 1370 (23.65) | 789 (29.53) | ||

| Former | 322 (3.80) | 175 (3.02) | 147 (5.50) | ||

| Presence of Hypertension, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||||

| No | 5768 (68.15) | 4045 (69.84) | 1723 (64.48) | ||

| Yes | 2696 (31.85) | 1747 (30.16) | 949 (35.52) | ||

| Presence of Diabetes, n (%) | 0.1587 | ||||

| No | 7885 (93.16) | 5411 (93.42) | 2474 (92.59) | ||

| Yes | 579 (6.84) | 381 (6.58) | 198 (7.41) | ||

| Presence of Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 0.8637 | ||||

| No | 4081 (48.22) | 2789 (48.15) | 1292 (48.35) | ||

| Yes | 4383 (51.78) | 3003 (51.85) | 1380 (51.65) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2, median [Q1, Q3]) | 24 [22, 27] | 24 [22, 27] | 24 [22, 27] | 0.3155 | |

| BMI, n (%) | 0.1457 | ||||

| Normal | 3941 (46.56) | 2728 (47.10) | 1213 (45.40) | ||

| Overweight | 3152 (36.92) | 2098 (36.22) | 1027 (38.44) | ||

| Obese | 1398 (16.52) | 966 (16.68) | 432 (16.17) | ||

| Laboratory Features (median [Q1, Q3]) | |||||

| Lipid Subclasses | |||||

| VLDL (mmol/L) | 0.25 [0.17, 0.38] | 0.25 [0.17, 0.38] | 0.24 [0.17, 0.37] | 0.0804 | |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.44 [2.05, 2.87] | 2.46 [2.06, 2.89] | 2.39 [2.02, 2.82] | <0.0001 | |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.16 [1.00, 1.35] | 1.17 [1.01, 1.36] | 1.13 [0.98, 1.33] | <0.0001 | |

| ApoA1 (g/L) | 1.22 [1.12, 1.33] | 1.23 [1.13, 1.34] | 1.21 [1.11, 1.32] | <0.0001 | |

| ApoB (g/L) | 0.96 [0.82, 1.13] | 0.97 [0.82, 1.15] | 0.95 [0.81 1.09] | <0.0001 | |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.38 [3.83, 5.00] | 4.43 [3.87, 5.05] | 4.28 [3.74, 4.90] | <0.0001 | |

| TGs (mmol/L) | 1.24 [0.85, 1.88] | 1.24 [0.85, 1.90] | 1.22 [0.85, 1.84] | 0.0798 | |

| Other Parameters | |||||

| ALT (U/L) | 18.6 [13.1, 28.5] | 18.1 [12.8, 27.2] | 20.1 [14.1, 30.7] | <0.0001 | |

| AST (U/L) * | 21.0 [18.0, 26.0] | 21.0 [18.0, 25.0] | 22.0 [18.0, 27.0] | <0.0001 | |

| GGT (U/L) | 19.6 [13.3, 32.0] | 18.6 [13.0, 30.0] | 22.0 [14.7, 35.8] | <0.0001 | |

| ALP (U/L) | 65.0 [54.0, 79.0] | 65.0 [54.0, 79.0] | 66.0 [55.0, 78.0] | 0.2877 | |

| sCr (µmol/L) | 76.1 [66.8, 85.9] | 73.8 [65.6, 84.2] | 80.6 [70.6, 88.6] | <0.0001 | |

| UA (µmol/L) | 289 [231, 354] | 280 [226, 345] | 307 [247, 372] | <0.0001 | |

| eGFR (mL/(min·1.73 m2)) | 97.5 [86.4, 108.4] | 97.5 [86.0, 108.4] | 97.3 [87.2, 108.3] | 0.5228 | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.0 [4.7, 5.4] | 5.0 [4.7, 5.4] | 5.0 [4.7, 5.4] | 0.9566 | |

| Drug Use | |||||

| Statins or Fibrate Use, n (%) | 0.6625 | ||||

| No | 8356 (98.72) | 5716 (98.96) | 2640 (98.80) | ||

| Yes | 108 (1.28) | 76 (1.31) | 32 (1.20) | ||

| Subgroup | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI), p | OR (95% CI), p | OR (95% CI), p | ||

| Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Total participants | 0.992 (0.905, 1.087), 0.8636 | 0.710 (0.641, 0.785), <0.0001 | 0.764 (0.686, 0.851), <0.0001 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <65 | 1.008 (0.917, 1.107), 0.8702 | 0.704 (0.634, 0.781), <0.0001 | 0.762 (0.682, 0.851), <0.0001 | |

| ≥65 | 0.729 (0.474, 1.120), 0.1489 | 0.718 (0.463, 1.115), 0.1401 | 0.755 (0.475, 1.198), 0.2326 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.752 (0.663, 0.852), <0.0001 | 0.749 (0.661, 0.849), <0.0001 | 0.823 (0.720, 0.942), 0.0046 | |

| Female | 0.674 (0.572, 0.794), <0.0001 | 0.644 (0.541, 0.767), <0.0001 | 0.665 (0.554, 0.799), <0.0001 | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 0.985 (0.856, 1.072), 0.4530 | 0.697 (0.615, 0.791), <0.0001 | 0.708 (0.618, 0.811), <0.0001 | |

| Current | 0.798 (0.661, 0.964), 0.0191 | 0.784 (0.649, 0.948), 0.0122 | 0.831 (0.672, 1.027), 0.0866 | |

| Former | 0.776 (0.483, 1.246), 0.2936 | 0.769 (0.478, 1.237), 0.2789 | 0.685 (0.397, 1.183), 0.1750 | |

| Subclass | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI), p | OR (95% CI), p | OR (95% CI), p | |

| Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Sterol Lipid | |||

| TC ≥ 5.2 | 0.786 (0.697, 0.887), <0.0001 | 0.741 (0.653, 0.842), <0.0001 | 0.730 (0.640, 0.833), <0.0001 |

| Neutral Lipid | |||

| TG ≥ 1.7 | 0.920 (0.833, 1.018), 0.1056 | 0.697 (0.627, 0.776), <0.0001 | 0.715 (0.634, 0.806), <0.0001 |

| Lipoproteins | |||

| LDL-C ≥ 3.4 | 0.786 (0.655, 0.944), 0.0099 | 0.752 (0.622, 0.909), 0.0032 | 0.763 (0.628, 0.925), 0.0061 |

| HDL-C < 1.0 | 1.208 (1.088, 1.342), 0.0004 | 0.875 (0.783, 0.978), 0.0184 | 0.955 (0.851, 1.072), 0.4349 |

| VLDL-C ≥ 0.78 | 0.902 (0.720, 1.130), 0.3687 | 0.680 (0.540, 0.857), 0.0011 | 0.696 (0.542, 0.893), 0.0043 |

| Apolipoproteins | |||

| ApoA1 < 1.0 | 1.386 (1.134, 1.694), 0.0015 | 1.048 (0.852, 1.288), 0.6581 | 1.134 (0.918, 1.401), 0.2437 |

| ApoB ≥ 1.2 | 0.808 (0.721, 0.905), 0.0002 | 0.684 (0.606, 0.773), <0.0001 | 0.698 (0.615, 0.792), <0.0001 |

| ApoB/ApoA1 ratio ≥ 1.2 | 0.883 (0.773, 1.007), 0.0641 | 0.729 (0.634, 0.837), <0.0001 | 0.765 (0.662, 0.883), 0.0003 |

| Characteristic | Total | Nonhyperbilirubinemia | Hyperbilirubinemia | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 2426 | n = 1656 | n = 770 | ||

| Age (years, median [Q1, Q3]) | 57 [49, 61] | 57 [49, 61] | 57 [49, 61] | 0.7032 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 1200 (49.46) | 672 (40.58) | 528 (68.57) | <0.0001 |

| Presence of Hypertension, n (%) | 1196 (49.30) | 792 (47.83) | 404 (52.47) | 0.0333 |

| Presence of Diabetes, n (%) | 323 (13.31) | 211 (12.74) | 112 (14.55) | 0.2235 |

| Presence of Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 1494 (61.58) | 1039 (62.74) | 455 (59.09) | 0.0853 |

| Presence of Arterial Stenosis, n (%) | 636 (26.22) | 432 (26.09) | 204 (26.49) | 0.8322 |

| Presence of CAC, n (%) | 178 (7.34) | 114 (6.88) | 64 (8.31) | 0.2094 |

| BMI (kg/m2, median [Q1, Q3]) | 25 [23, 27] | 25 [23, 27] | 25 [23, 27] | 0.0937 |

| Presence of Obesity, n (%) | 433 (17.85) | 300 (18.12) | 133 (17.27) | 0.6137 |

| Presence of Metabolic Syndrome, n (%) | 1067 (43.98) | 743 (44.87) | 324 (42.08) | 0.1976 |

| Presence of NAFLD *, n (%) | 1381 (56.92) | 915 (55.25) | 466 (60.52) | 0.0167 |

| Presence of CKD, n (%) | 61 (2.51) | 46 (2.78) | 15 (1.95) | 0.2244 |

| Disease | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI), p | OR (95% CI), p | OR (95% CI), p | |

| Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Cardiovascular Diseases 1 | |||

| Arterial stenosis | 1.021 (0.841, 1.240), 0.8319 | 0.825 (0.673, 1.011), 0.0642 | 0.806 (0.653, 0.996), 0.0462 |

| CAC | 1.226 (0.891, 1.687), 0.2100 | 1.033 (0.734, 1.453), 0.8527 | 1.084 (0.763, 1.539), 0.6526 |

| Metabolic Diseases | |||

| Obesity | 0.964 (0.851, 1.091), 0.5584 | 0.788 (0.693, 0.896), 0.0003 | 0.747 (0.649, 0.860), <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1.275 (1.157, 1.405), <0.0001 | 1.025 (0.918, 1.143), 0.6614 | 1.111 (0.986, 1.252), 0.0847 |

| Diabetes | 1.137 (0.951, 1.358), 0.1589 | 0.993 (0.820, 1.203), 0.9463 | 1.012 (0.830, 1.234), 0.9060 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 0.898 (0.812, 0.993), 0.0356 | 0.764 (0.685, 0.852), <0.0001 | 0.784 (0.680, 0.904), 0.0008 |

| Other Diseases | |||

| NAFLD * | 1.147 (1.046, 1.257), 0.0034 | 0.829 (0.749, 0.917), 0.0003 | 0.940 (0.829, 1.064), 0.3265 |

| CKD | 0.795 (0.502, 1.260), 0.3293 | 0.851 (0.526, 1.376), 0.5096 | 0.837 (0.508, 1.381), 0.4864 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, B.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Han, D.; Chen, Y. Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid Profile and Lipid-Related Diseases: A Large Community-Based Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020455

Yu B, Liu Y, Wu W, Zhou Y, Han D, Chen Y. Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid Profile and Lipid-Related Diseases: A Large Community-Based Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020455

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Borong, Yuhe Liu, Wenqian Wu, Yong Zhou, Dan Han, and Yuanwen Chen. 2026. "Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid Profile and Lipid-Related Diseases: A Large Community-Based Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020455

APA StyleYu, B., Liu, Y., Wu, W., Zhou, Y., Han, D., & Chen, Y. (2026). Association of Hyperbilirubinemia with Lipid Profile and Lipid-Related Diseases: A Large Community-Based Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020455