Serum Outperforms Plasma for Glypican-3 Quantification in Hepatocellular Carcinoma—A Prospective Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Participants

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. Measurement of GPC3

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

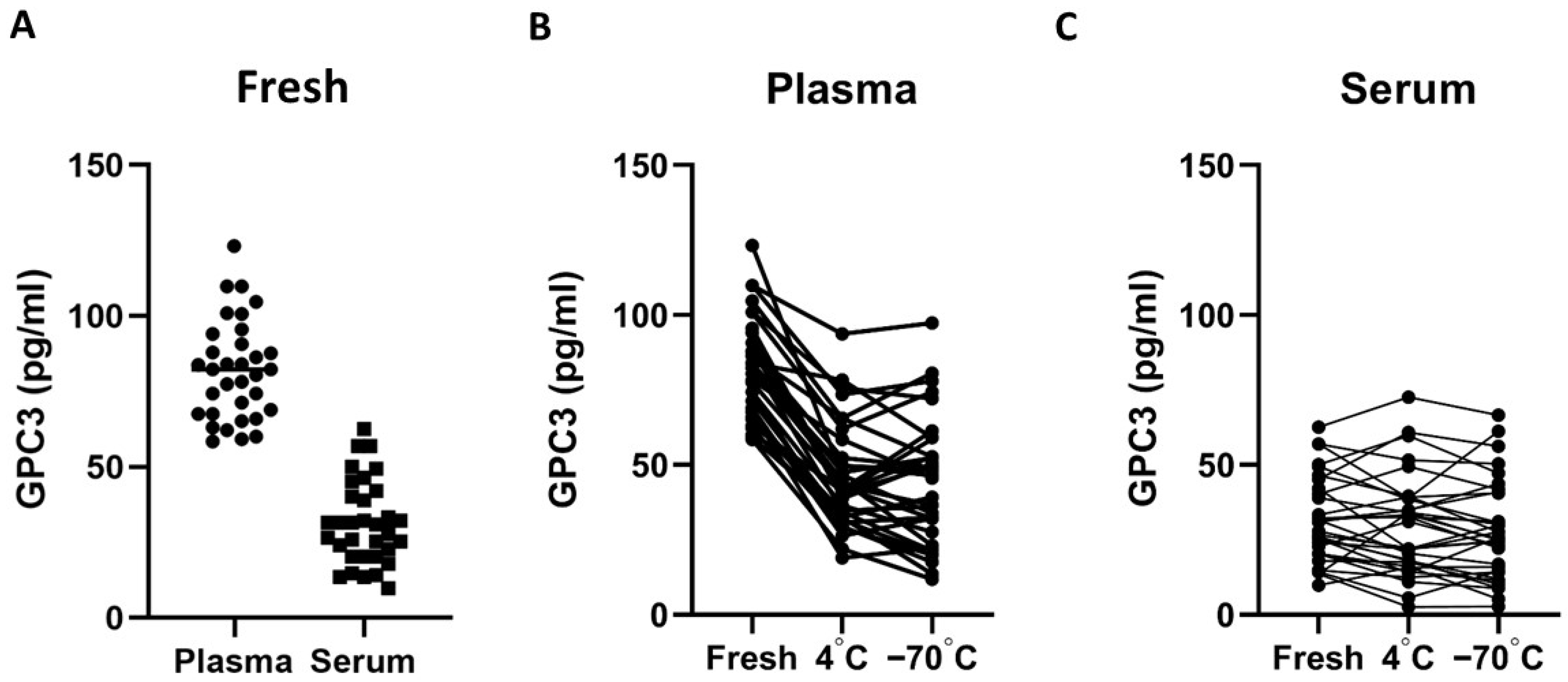

3.2. Serum vs. Plasma Stability

3.3. Correlation Analysis Between Plasma and Serum

3.4. Comparison Amongst Clinical Groups

3.5. Diagnostic Performance Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Villanueva, A.; Lachenmayer, A.; Finn, R.S. Advances in targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma in the genomic era. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Kelley, R.K.; Villanueva, A.; Singal, A.G.; Pikarsky, E.; Roayaie, S.; Lencioni, R.; Koike, K.; Zucman-Rossi, J.; Finn, R.S. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Wang, H. Precision diagnosis and treatment of liver cancer in China. Cancer Lett. 2018, 412, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.Y.; Toan, B.N.; Tan, C.-K.; Hasan, I.; Setiawan, L.; Yu, M.-L.; Izumi, N.; Huyen, N.N.; Chow, P.K.-H.; Mohamed, R.; et al. Utility of combining PIVKA-II and AFP in the surveillance and monitoring of hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia-Pacific region. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Shang, W.; Yu, X.; Tian, J. Glypican-3: A promising biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and treatment. Med. Res. Rev. 2018, 38, 741–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devan, A.R.; Nair, B.; Pradeep, G.K.; Alexander, R.; Vinod, B.S.; Nath, L.R.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J. The role of glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Insights into diagnosis and therapeutic potential. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumhoer, D.; Tornillo, L.; Stadlmann, S.; Roncalli, M.; Diamantis, E.K.; Terracciano, L.M. Glypican 3 expression in human nonneoplastic, preneoplastic, and neoplastic tissues: A tissue microarray analysis of 4,387 tissue samples. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2008, 129, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Urban, D.J.; Nani, R.R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Fu, H.; Shah, H.; Gorka, A.P.; Guha, R.; Chen, L.; et al. Glypican-3-Specific Antibody Drug Conjugates Targeting Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2019, 70, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jin, R.; Zhang, X.; Lv, F.; Liu, L.; Liu, D.; Liu, K.; Li, N.; Chen, D. Oncogenic activation of glypican-3 by c-Myc in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2012, 56, 1380–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, M.; Ugo, P.; Walton, Z.; Ali, S.; Rastellini, C.; Cicalese, L. Glypican-3 (GPC-3) Structural Analysis and Cargo in Serum Small Extracellular Vesicles of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Su, C.; Sun, L.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y. Performance of Serum Glypican 3 in Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Ann. Hepatol. 2019, 18, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, A.; Gaia, S.; Risso, A.; Rosso, C.; Rolle, E.; Abate, M.L.; Olivero, A.; Armandi, A.; Ribaldone, D.G.; Carucci, P.; et al. Serum glypican-3 for the prediction of survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Minerva Gastroenterol. 2022, 68, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehrani, H.A.; Zangi, M.; Fathi, M.; Vakili, K.; Hassan, M.; Rismani, E.; Hossein-Khannazer, N.; Vosough, M. GPC-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma; A novel biomarker and molecular target. Exp. Cell Res. 2025, 444, 114391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y. Glypican-3: A New Target for Diagnosis and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 2008–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffin, D.; Ghatwai, N.; Montalbano, A.; Rathi, P.; Courtney, A.N.; Arnett, A.B.; Fleurence, J.; Sweidan, R.; Wang, T.; Zhang, H.; et al. Interleukin-15-armoured GPC3 CAR T cells for patients with solid cancers. Nature 2025, 637, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.E.; Kim, S.Y.; Shin, S.Y. Effect of Repeated Freezing and Thawing on Biomarker Stability in Plasma and Serum Samples. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2015, 6, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J.L.; Vaquerano, J.T.; Taylor, E.B. Isolated Effects of Plasma Freezing versus Thawing on Metabolite Stability. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuhadar, S.; Koseoglu, M.; Atay, A.; Dirican, A. The effect of storage time and freeze-thaw cycles on the stability of serum samples. Biochem. Med. 2013, 23, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, J.; Xiao, Z.; Cui, Z. Diagnostic and prognostic performance of serum GPC3 and PIVKA-II in AFP-negative hepatocellular carcinoma and establishment of nomogram prediction models. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, T.; Kataoka, H. Glypican 3-Targeted Therapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2019, 11, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M.; Fujinami, N.; Shimizu, Y.; Mizuno, S.; Saito, K.; Suzuki, T.; Konishi, M.; Takahashi, S.; Gotohda, N.; Suto, K.; et al. Usefulness of plasma full-length glypican-3 as a predictive marker of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after radial surgery. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 19, 2657–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Mizuno, S.; Fujinami, N.; Suzuki, T.; Saito, K.; Konishi, M.; Takahashi, S.; Gotohda, N.; Tada, T.; Toyoda, H.; et al. Plasma and tumoralglypican-3 levels are correlated in patients with hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Du, Z. Diagnosis accuracy of serum glypican-3 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Arch. Med. Res. 2014, 45, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Saadny, S.; El-Demerdash, T.; Helmy, A.; Mayah, W.W.; Hussein, B.E.-S.; Hassanien, M.; Elmashad, N.; Fouad, M.A.; Basha, E.A. Diagnostic Value of Glypican-3 for Hepatocellular Carcinomas. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 19, 811–817. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-S.; Lee, T.-Y.; Chou, R.-H.; Yen, C.-J.; Huang, W.-C.; Wu, C.-Y.; Yu, Y.-L. Development of a highly sensitive glycan microarray for quantifying AFP-L3 for early prediction of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batbaatar, B.; Gurbadam, U.; Tuvshinsaikhan, O.; Narmandakh, N.-E.; Khatanbaatar, G.; Radnaabazar, M.; Erdene-Ochir, D.; Boldbaatar, M.; Byambaragchaa, M.; Amankyeldi, Y.; et al. Evaluation of glypican-3 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valo, E.; Colombo, M.; Sandholm, N.; McGurnaghan, S.J.; Blackbourn, L.A.K.; Dunger, D.B.; McKeigue, P.M.; Forsblom, C.; Groop, P.-H.; Colhoun, H.M.; et al. Effect of serum sample storage temperature on metabolomic and proteomic biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Lazcano, D.G.; Simón-Lara, I.; Morales-Romero, J.; Vásquez-Garzón, V.R.; Arroyo-Helguera, O.E.; López-Vazquez, J.; Campos-Parra, A.D.; Hernández-Nopaltecatl, B.; Rivera-Hernández, X.A.; Quintana, S.; et al. Alpha-fetoprotein, glypican-3, and kininogen-1 as biomarkers for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2024, 17, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Lu, W.; Zeng, Y. Prognostic significance of glypican-3 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e9702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.K.; Qi, C.Y.; Chen, D.; Li, S.Q.; Fu, S.J.; Peng, B.G.; Liang, L.J. Prognostic significance of glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, R.; Xiang, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; He, H.; Huang, L.; Zuo, D.; Li, W.; et al. Combination Therapy of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by GPC3-Targeted Bispecific Antibody and Irinotecan is Potent in Suppressing Tumor Growth in Mice. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S.; Lee, T.Y.; Chao, H.W. Targeting glypican-3 as a new frontier in liver cancer therapy. World J. Hepatol. 2025, 17, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-W.; Huang, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.-C.; Tsai, H.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Chang, C.-H.; Lee, T.-Y.; Peng, Y.-C. CRAFITY and AFP/PIVKA-II Kinetics Predict Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma on Immunotherapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Health Control (n = 33) | CLD (n = 29) | HCC (n = 38) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.0 (50.0, 73.0) | 55.0 (50.5, 64.5) | 65.5 (58.8, 73.5) | <0.01 |

| Male gender (n) | 21 | 18 | 29 | <0.01 |

| Height (cm) | 163.4 (156.7, 167.8) | 165.0 (156.0, 170.5) | 164.1 (158.6, 171.3) | 0.53 |

| Body weight (kg) | 58.3 (49.5, 64.8) | 70.8 (65.7, 78.1) | 60.9 (53.8, 73.5) | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.9 (19.7, 24.5) | 26.9 (23.4, 28.6) | 23.1 (20.8, 25.4) | <0.01 |

| Smoking (n) | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0.18 |

| Alcohol drinking (n) | 0 | 10 | 15 | <0.01 |

| HBV infection (n) | 0 | 10 | 18 | <0.01 |

| HCV infection (n) | 0 | 2 | 5 | <0.01 |

| AST (U/L) | 20.0 (17.5, 27.5) | 44.0 (32.5, 66.0) | 64.5 (35.5, 105.0) | 0.15 |

| ALT (U/L) | 15.0 (11.0, 20.0) | 44.0 (33.0, 87.0) | 29.0 (17.0, 60.0) | <0.01 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.3) | 0.7 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.89 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.3 (4.1, 4.4) | 4.6 (4.3, 4.8) | 3.9 (3.3, 4.3) | 0.11 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) | 0.05 |

| White blood cell (mm3) | 5470 (4765, 6428) | 6180 (4760, 6815) | 6515 (4918, 8608) | 0.01 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.4 (12.6, 14.8) | 14.1 (12.9, 15.7) | 13.2 (10.4, 14.6) | <0.01 |

| Platelet (mm3) | 233.0 (181.0, 292.5) | 234.0 (186.8, 267.8) | 172.0 (116.3, 234.8) | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, M.-T.; Wang, J.-M.; Wu, C.-S.; Lee, S.-W.; Tsai, H.-J.; Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Liu, H.-F.; Lee, T.-Y. Serum Outperforms Plasma for Glypican-3 Quantification in Hepatocellular Carcinoma—A Prospective Comparative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020448

Yang M-T, Wang J-M, Wu C-S, Lee S-W, Tsai H-J, Chen C-C, Lin Y-C, Liu H-F, Lee T-Y. Serum Outperforms Plasma for Glypican-3 Quantification in Hepatocellular Carcinoma—A Prospective Comparative Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020448

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ming-Tze, Jiunn-Min Wang, Chen-Shiou Wu, Shou-Wu Lee, Hsin-Ju Tsai, Chia-Chang Chen, Ying-Cheng Lin, Hui-Fen Liu, and Teng-Yu Lee. 2026. "Serum Outperforms Plasma for Glypican-3 Quantification in Hepatocellular Carcinoma—A Prospective Comparative Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020448

APA StyleYang, M.-T., Wang, J.-M., Wu, C.-S., Lee, S.-W., Tsai, H.-J., Chen, C.-C., Lin, Y.-C., Liu, H.-F., & Lee, T.-Y. (2026). Serum Outperforms Plasma for Glypican-3 Quantification in Hepatocellular Carcinoma—A Prospective Comparative Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020448