A 10-Year Study on Percutaneous Cholecystostomy for Acute Cholecystitis at a Tertiary Referral Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. PC Technique

2.3. Data Collection and Definitions

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Percutaneous Cholecystostomy: Procedure Characteristics and Short-Term Outcomes

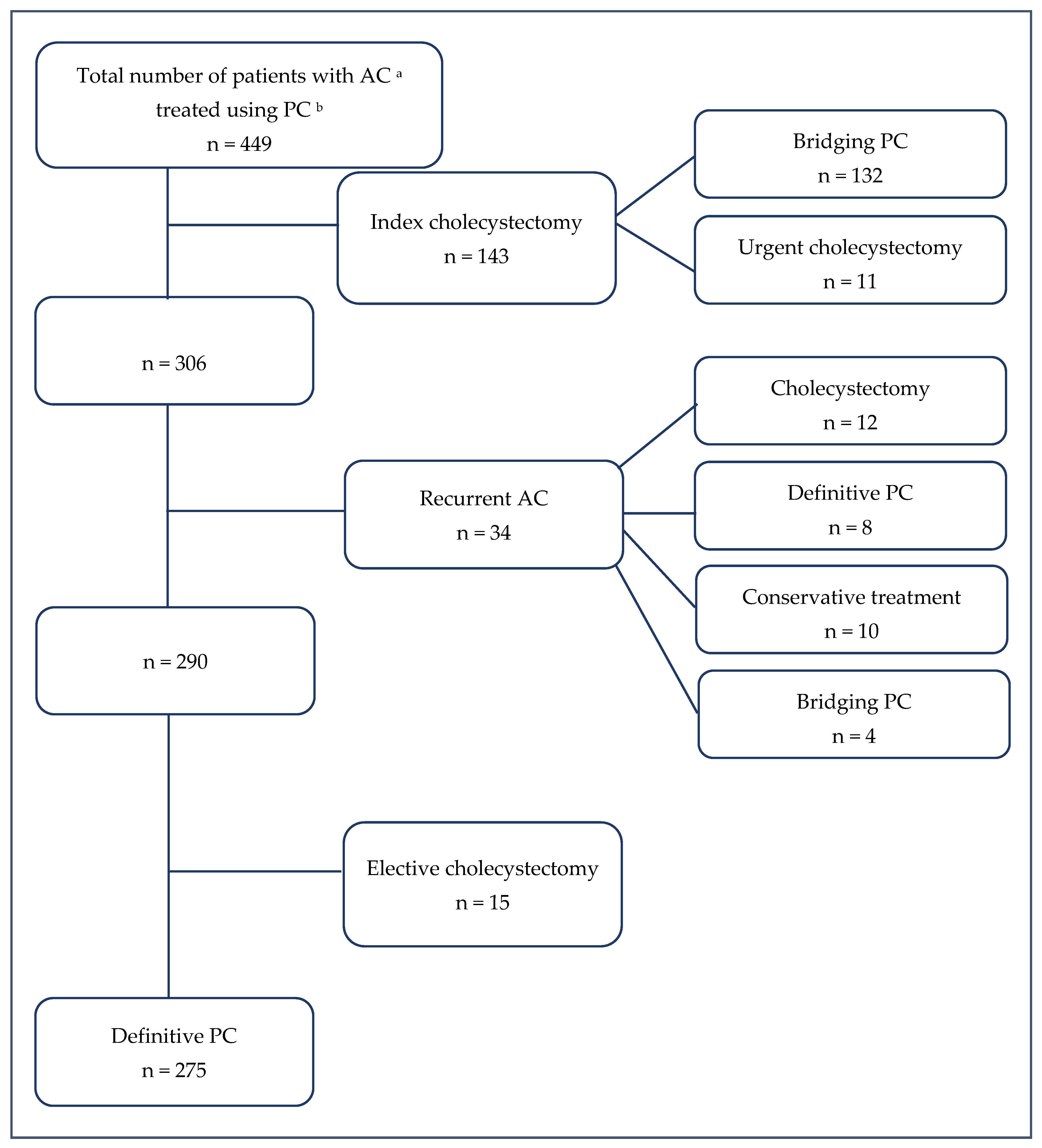

3.3. Surgical Treatment Following PC

3.4. Follow-Up: Long-Term Outcomes and Risk Factors for In-Hospital Mortality

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mencarini, L.; Vestito, A.; Zagari, R.M.; Montagnani, M. The diagnosis and treatment of acute cholecystitis: A comprehensive narrative review for a practical approach. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Guan, L.J.; Ouyang, R.; Chen, Z.X.; Ouyang, G.Q.; Jiang, H.X. Global, regional, and national burden of gallbladder and biliary diseases from 1990 to 2019. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 2564–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Suzuki, K.; Takada, T.; Strasberg, S.M.; Asbun, H.J.; Endo, I.; Iwashita, Y.; Hibi, T.; Pitt, H.A.; Umezawa, A.; et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2018, 25, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Cai, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Dai, Y. Global burden of gallbladder and biliary diseases (1990-2021) with healthcare workforce analysis and projections to 2035. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannam, R.; Sankara Narayanan, R.; Bansal, A.; Yanamaladoddi, V.R.; Sarvepalli, S.S.; Vemula, S.L.; Aramadaka, S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus open cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis: A literature review. Cureus 2023, 15, e45704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.M.; Eslick, G.D.; Cox, M.R. Early Cholecystectomy Is Superior to Delayed Cholecystectomy for Acute Cholecystitis: A Meta-analysis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2015, 19, 848–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, T.; Christensen, S.D.; Kirkegård, J.; Larsen, L.P.; Knudsen, A.R.; Mortensen, F.V. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an effective treatment option for acute calculous cholecystitis: A 10-year experience. HPB 2015, 17, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Miedema, B.W.; James, M.A.; Marshall, J.B. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an effective treatment for high-risk patients with acute cholecystitis. Am. Surg. 2000, 66, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkegård, J.; Horn, T.; Christensen, S.D.; Larsen, L.P.; Knudsen, A.R.; Mortensen, F.V. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an effective definitive treatment option for acute acalculous cholecystitis. Scand. J. Surg. 2015, 104, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarour, S.; Imam, A.; Kouniavsky, G.; Lin, G.; Zbar, A.; Mavor, E. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in the management of high-risk patients presenting with acute cholecystitis: Timing and outcome at a single institution. Am. J. Surg. 2017, 214, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramia, J.M.; Serradilla-Martín, M.; Villodre, C.; Rubio, J.J.; Rotellar, F.; Siriwardena, A.K.; Wakabayashi, G.; Catena, F. International Delphi consensus on the management of percutaneous choleystostomy in acute cholecystitis (E-AHPBA, ANS, WSES societies). World J. Emerg. Surg. 2024, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirocchi, R.; Amato, L.; Ungania, S.; Buononato, M.; Tebala, G.D.; Cirillo, B.; Avenia, S.; Cozza, V.; Costa, G.; Davies, R.J.; et al. Management of acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: Percutaneous gallbladder drainage as a definitive treatment vs. emergency cholecystectomy-systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoe, M.; Hata, J.; Takada, T.; Strasberg, S.M.; Asbun, H.J.; Wakabayashi, G.; Kozaka, K.; Endo, I.; Deziel, D.J.; Miura, F.; et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholecystitis (with videos). J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2018, 25, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisano, M.; Allievi, N.; Gurusamy, K.; Borzellino, G.; Cimbanassi, S.; Boerna, D.; Coccolini, F.; Tufo, A.; Di Martino, M.; Leung, J.; et al. 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute calculus cholecystitis. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2020, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escartín, A.; González, M.; Cuello, E.; Pinillos, A.; Muriel, P.; Merichal, M.; Palacios, V.; Escoll, J.; Gas, C.; Olsina, J.-J. Acute cholecystitis in very elderly patients: Disease management, outcomes, and risk factors for complications. Surg. Res. Pract. 2019, 2019, 9709242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winbladh, A.; Gullstrand, P.; Svanvik, J.; Sandström, P. Systematic review of cholecystostomy as a treatment option in acute cholecystitis. HPB 2009, 11, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, C.A.; Ismail, M.; Kavanagh, R.G.; Heneghan, H.M.; Prichard, R.S.; Geoghegan, J.; Brophy, D.P.; McDermott, E.W. Clinical and survival outcomes using percutaneous cholecystostomy tube alone or subsequent interval cholecystectomy to treat acute cholecystitis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 24, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, M.A.; Manzoor, S.V.; Reshi, F.A.; Zargar, W.A.; Jeelani, S.; Ahmad, F.F.; Ko, A.Z.; Singh, B. Percutaneous Cholecystostomy in high risk patients with acute cholecystitis. Surg. Sci. 2017, 8, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.Y.; Gwon, D.I.; Ko Gy Yoon, H.K.; Sung, K.B. Role of percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis: Clinical outcomes of 271 patients. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 24, 1449–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.C.; Chen, C.K.; Su, C.W.; Chan, C.-C.; Huo, T.-I.; Liu, C.-J.; Fang, W.-L.; Lee, K.-C.; Lin, H.-C. Outcome after percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis: A single-center experience. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2012, 16, 1860–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, P.; Mittapalli, D.; Marioud, A.; White, R.D.; Ram, R.; Alijani, A. Clinical outcomes of a percutaneous cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis: A multicentre analysis. HPB 2013, 15, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Rodrigues, S.; Fonseca, T.; Costa, R.M.; Teixeira, J.A. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in the management of calculous acute cholecystitis. Port. J. Surg. 2020, 47, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinillos, A.; Gómez, F.D.; Muriel, P.; Escartín, A.; Jara, J.; González, M.; Salvador, H.; Fulthon, F.; Olsina, J. Bile duct injuries during urgent cholecystectomy: Analysis of 1320 acute cholecystitis cohort. HPB 2021, 23, S781–S782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, C.; Frozanpor, F.; Linder, S. Bile duct injuries at laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A single-institution prospective study. acute cholecystitis indicates an increased risk. World J. Surg. 2005, 29, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, J.F.; Trenk, A.; Kuchta, K.; Lapin, B.; Denham, W.; Linn, J.G.; Haggerty, S.; Joehl, R.; Ujiki, M.B. Characterization of common bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a high-volume hospital system. Surg. Endosc. 2018, 32, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loozen, C.S.; van Ramshorst, B.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Boerma, D. Early cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in the elderly population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig. Surg. 2017, 34, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.H.; Wu, C.Y.; Yang, J.C.; Lien, W.C.; Wang, H.P.; Liu, K.L.; Wu, Y.-M.; Chen, S.-C. Long-term outcomes of patients with acute cholecystitis after successful percutaneous cholecystostomy treatment and the risk factors for recurrence: A decade experience at a single center. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, M.N.; Ghio, M.; Sadri, L.; Sarkar, S.; Kasotakis, G.; Narsule, C.; Sarkar, B. Percutaneous cholecystostomy in acute cholecystitis-predictors of recurrence and interval cholecystectomy. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 232, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, C.S.; Tay, V.W.; Low, J.K.; Woon, W.W.; Punamiya, S.J.; Shelat, V.G. Outcomes of percutaneous cholecystostomy and predictors of eventual cholecystectomy. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2016, 23, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | All Patients, n = 449 |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 80 (73.0–85.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 194 (43.2) |

| Female | 255 (56.8) |

| ASA classification a, n (%) | |

| ASA I | 3 (0.7) |

| ASA II | 44 (9.8) |

| ASA III | 207 (46.1) |

| ASA IV | 195 (43.4) |

| Sepsis, n (%) | |

| Presence of sepsis | 104 (23.2) |

| TG18 severity of AC b, n (%) | |

| Grade I | 68 (15.1) |

| Grade II | 280 (62.4) |

| Grade III | 101 (22.5) |

| Type of cholecystitis, n (%) | |

| Calculous | 424 (94.4) |

| Acalculous | 25 (5.6) |

| Laboratory data on admission | |

| WBC c (×109/L) | 13.6 (10.5–18.0) |

| CRP d (mg/L) | 161.6 (60.2–269.65) |

| Time to PC e insertion (median, IQR) | 1 (1–2) |

| Admission day | 59 (13.1) |

| Day 1 | 172 (38.3) |

| Day 2 | 77 (17.1) |

| Day 3 | 33 (7.3) |

| Others | 108 (24.1) |

| Procedure complication, n (%) | |

| Dislocation | 8 (1.8) |

| Occlusion | 2 (0.4) |

| Bile leak | 13 (2.9) |

| Bleeding | 2 (0.4) |

| Other | 12 (2.7) |

| Duration of PC treatment, days, median (IQR) | 9 (6–14) |

| Clinical outcomes | |

| ICU f admission, n (%) | 79 (17.6) |

| Hospital stay, days, median (IQR) | 12 (9–15) |

| Readmission cause, n (%) | 66 (14.7) |

| Pain | 6 (1.3) |

| Recurrent AC | 34 (7.6) |

| Acute pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis | 19 (4.2) |

| Abscess (biloma) | 3 (0.7) |

| Catheter disfunction | 1 (0.2) |

| Others | 3 (0.7) |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 24 (5.3) |

| Variable | All Patients, n = 174 |

|---|---|

| Duration from drainage to index cholecystectomy, days, median (IQR) | 7 (4–12) |

| Cholecystectomy approach, n (%) | |

| LC a | 81 (46.6) |

| OC b | 84 (48.3) |

| Conversion surgery | 9 (5.2) |

| Complications after cholecystectomy, n (%) | 6 (3.5) |

| BDI c | 3 (1.7) |

| Blood vessel injury | 1 (0.6) |

| Bile leak | 1 (0.6) |

| Wound eventration | 1 (0.6) |

| Variable | Definitive PC n = 275 | Bridging PC n = 174 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 81 (76–87) | 75 (68–81) | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.182 | ||

| Male | 112 (40.7) | 82 (47.1) | |

| Female | 163 (59.3) | 92 (52.9) | |

| ASA a classification, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| ASA I | 0 | 3 (1.7) | |

| ASA II | 16 (5.8) | 28 (16.1) | |

| ASA III | 108 (39.3) | 99 (56.9) | |

| ASA IV | 151 (54.9) | 44 (25.3) | |

| Sepsis, n (%) | |||

| Presence of sepsis | 64 (23.3) | 40 (23.0) | 0.945 |

| TG18 severity of AC b, n (%) | 0.454 | ||

| Grade I | 37 (13.5) | 31 (17.8) | |

| Grade II | 175 (63.6) | 105 (60.3) | |

| Grade III | 63 (22.9) | 38 (21.8) | |

| Laboratory data on admission | |||

| WBC c (×109/L) | 13.9 (10.5–17.6) | 13.0 (10.0–18.4) | 0.278 |

| CRP d (mg/L) | 174.1 (82.4–278.0) | 125.0 (47.0–243.0) | 0.003 |

| Duration of PC treatment, days, median (IQR) | 12 (7–14) | 7 (5–11) | <0.001 |

| ICU e admission, n (%) | 45 (16.4) | 34 (19.5) | 0.389 |

| Hospital stay, days, median (IQR) | 11 (8–14) | 13 (10–19) | <0.001 |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 23 (8.4) | 1 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Recurrent AC | 18 (6.5) | 16 (9.2) | 0.301 |

| Characteristics | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | reference | |||

| Female | 0.64 (0.29–1.44) | 0.282 | ||

| ASA a classification | ||||

| ASA I | reference | |||

| ASA II | 1.0 (0.0–5.37) | >0.99 | ||

| ASA III | 442.26 (0.0–3.15) | 0.952 | ||

| ASA IV | 3286.33 (0.0–2.33) | 0.936 | ||

| Sepsis | ||||

| Presence of sepsis | 8.06 (3.34–19.43) | <0.001 | 9.64 (1.31–70.77) | 0.026 |

| TG18 severity | ||||

| Grade I | reference | reference | ||

| Grade II | 1.7 (0.21–13.82) | 0.620 | 1.96 (0.23–16.8) | 0.539 |

| Grade III | 10.77 (1.43–81.23) | 0.021 | 1.49 (0.14–16.48) | 0.745 |

| Treatment strategy | ||||

| PC b alone | reference | reference | ||

| PC with cholecystectomy | 0.07 (0.01–0.51) | 0.009 | 0.07 (0.01–0.51) | 0.009 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ptasnuka, M.; Lazdane, I.; Fokins, V.; Kolesova, O.; Plaudis, H. A 10-Year Study on Percutaneous Cholecystostomy for Acute Cholecystitis at a Tertiary Referral Hospital. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020413

Ptasnuka M, Lazdane I, Fokins V, Kolesova O, Plaudis H. A 10-Year Study on Percutaneous Cholecystostomy for Acute Cholecystitis at a Tertiary Referral Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(2):413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020413

Chicago/Turabian StylePtasnuka, Margarita, Ita Lazdane, Vladimirs Fokins, Oksana Kolesova, and Haralds Plaudis. 2026. "A 10-Year Study on Percutaneous Cholecystostomy for Acute Cholecystitis at a Tertiary Referral Hospital" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 2: 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020413

APA StylePtasnuka, M., Lazdane, I., Fokins, V., Kolesova, O., & Plaudis, H. (2026). A 10-Year Study on Percutaneous Cholecystostomy for Acute Cholecystitis at a Tertiary Referral Hospital. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(2), 413. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15020413