Feasibility and Early and Midterm Outcomes of Midaortic Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

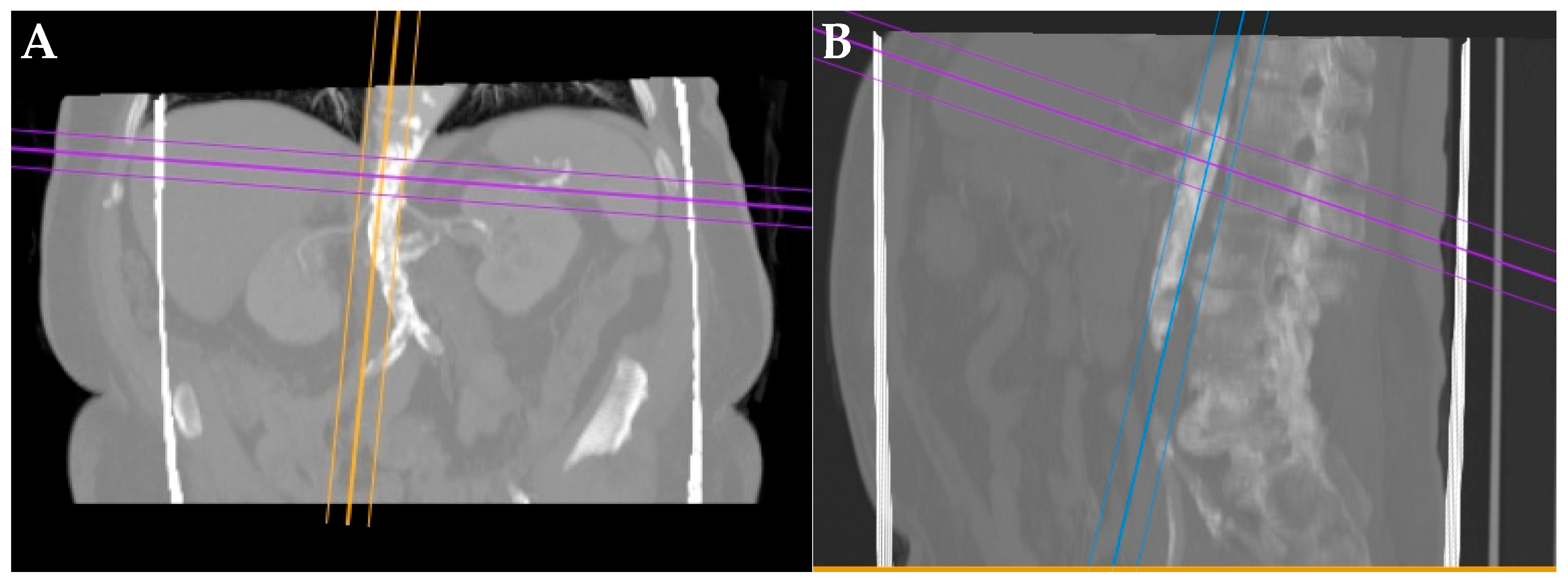

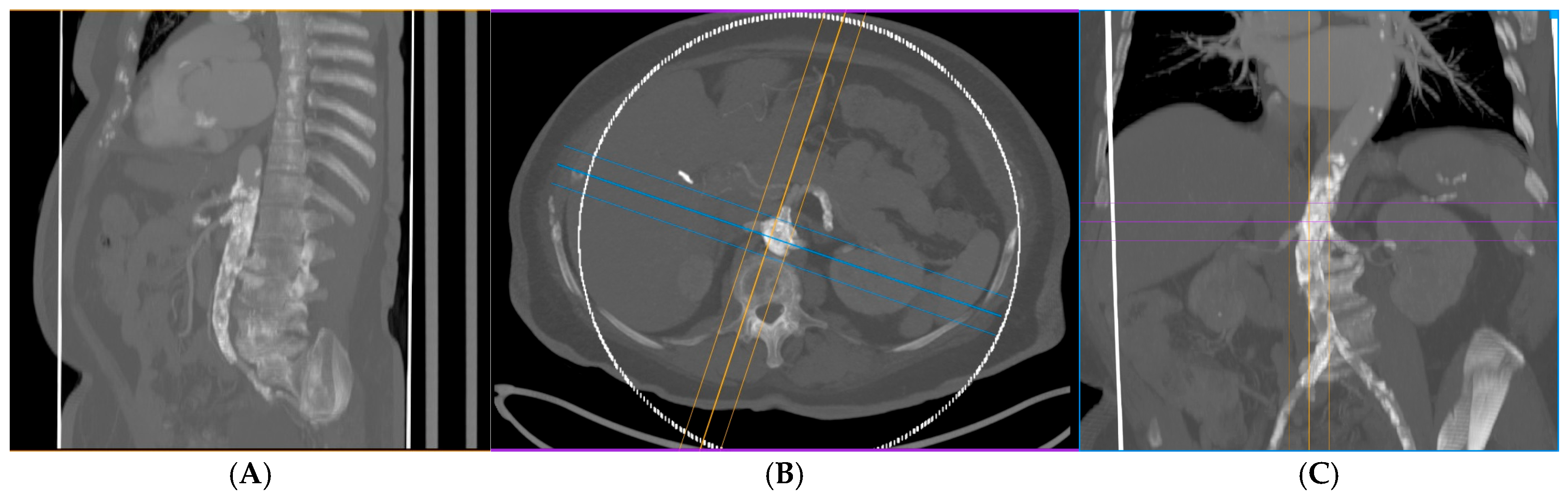

2.2. Preoperative Evaluation

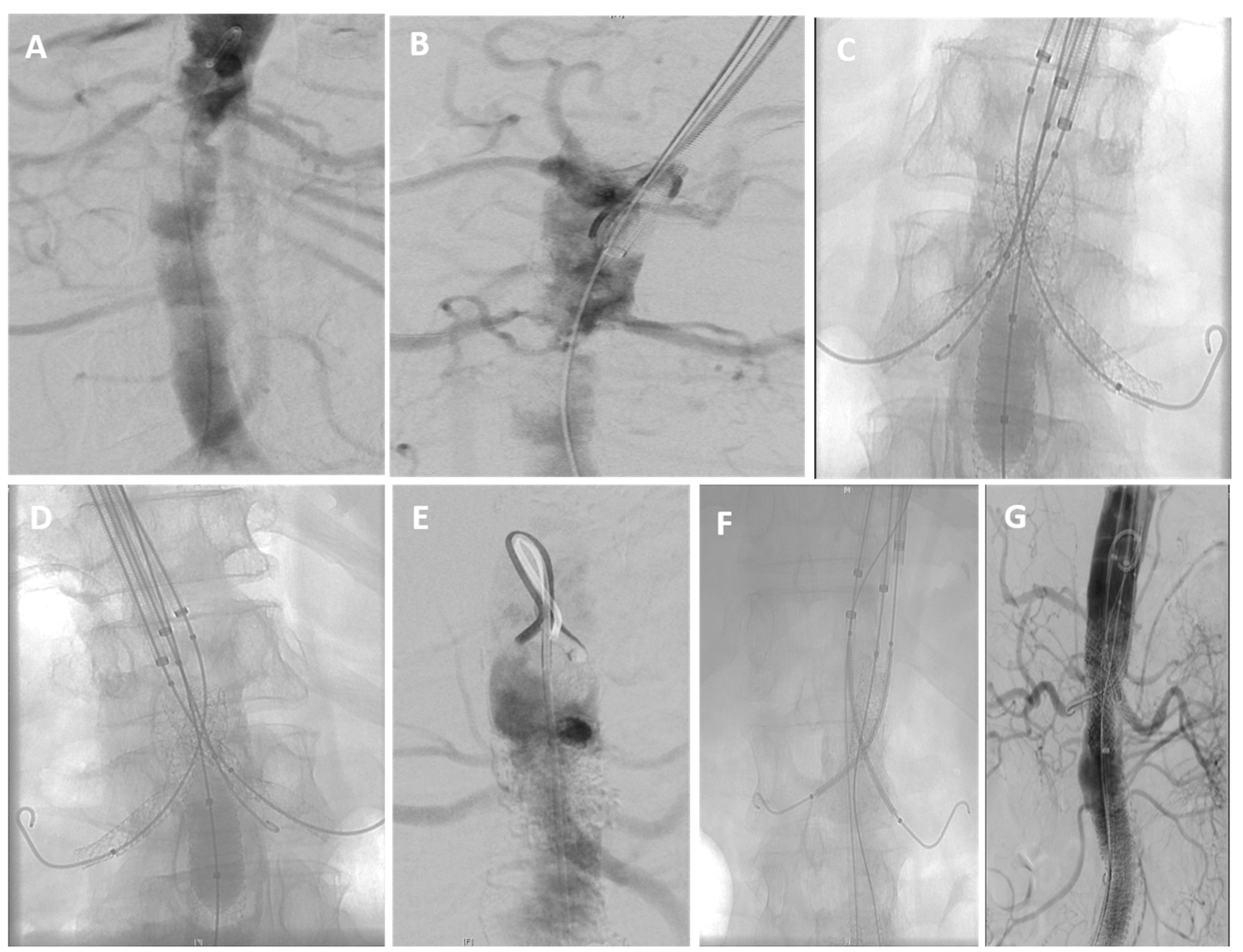

2.3. Endovascular Procedure

2.4. Postoperative Management and Follow-Up

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Patient Characteristics

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MAS | Midaortic Syndrome |

| TEA | Thoracoabdominal endarterectomy |

| CTA | Computed tomography angiography |

| SMA | Superior mesenteric artery |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TEVAR | Thoracic endovascular aortic repair |

| FEVAR | Fenestrated endovascular repair |

| ChEVAR | Chimney endovascular repair |

| AAA | Abdominal aortic aneurysms |

References

- Sen, P.K.; Kinare, S.G.; Engineer, S.D.; Parulkar, G.B. The middle aortic syndrome. Br. Heart J. 1963, 25, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.E.; Wilson, S.E.; Lawrence, P.L.; Fujitani, R.M. Middle aortic syndrome: Distal thoracic and abdominal coarctation, a disorder with multiple etiologies. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2002, 194, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delis, K.T.; Gloviczki, P. Middle aortic syndrome: From presentation to contemporary open surgical and endovascular treatment. Perspect. Vasc. Surg. Endovasc. Ther. 2005, 17, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porras, D.; Stein, D.R.; Ferguson, M.A.; Chaudry, G.; Alomari, A.; Vakili, K.; Fishman, S.J.; Lock, J.E.; Kim, H.B. Midaortic syndrome: 30 years of experience with medical, endovascular and surgical management. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2013, 28, 2023–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumman, R.K.; Nickel, C.; Matsuda-Abedini, M.; Lorenzo, A.J.; Langlois, V.; Radhakrishnan, S.; Amaral, J.; Mertens, L.; Parekh, R.S. Disease beyond the arch: A systematic review of middle aortic syndrome in childhood. Am. J. Hypertens. 2015, 28, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coselli, J.S.; LeMaire, S.A.; Preventza, O.; de la Cruz, K.I.; Cooley, D.A.; Price, M.D.; Stolz, A.P.; Green, S.Y.; Arredondo, C.N.; Rosengart, T.K. Outcomes of 3309 thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repairs. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 151, 1323–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.; LeMaire, S.A.; Weldon, S.A.; Coselli, J.S. Thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Open technique. Oper. Tech. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 15, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansagra, K.; Kang, J.; Taon, M.C.; Ganguli, S.; Gandhi, R.; Vatakencherry, G.; Lam, C. Advanced endografting techniques: Snorkels, chimneys, periscopes, fenestrations, and branched endografts. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2018, 8, S175–S183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, M.A.; Hamady, M. Various endoluminal approaches available for treating pathologies of the aortic arch. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2020, 43, 1756–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitoulias, G.A.; Fazzini, S.; Donas, K.P.; Scali, S.T.; D’Oria, M.; Torsello, G.; Veith, F.J.; Puchner, S.B. Multicenter mid-term outcomes of the chimney technique in the elective treatment of degenerative pararenal aortic aneurysms. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2022, 29, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glotzer, O.S.; Bowser, K.; Harad, F.T.; Weiss, S. Endovascular management of middle aortic syndrome presenting with uncontrolled hypertension. Case Rep. Vasc. Med. 2018, 2018, 9586025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlato, P.; Foresti, L.; Bloemert-Tuin, T.; Trimarchi, S.; Hazenberg, C.E.V.B.; van Herwaarden, J.A. Long-term outcomes of chimney endovascular aneurysm repair procedure for complex abdominal aortic pathologies. J. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 80, 612–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oderich, G.S.; Macedo, R.; Stone, D.H.; Woo, E.Y.; Panneton, J.M.; Resch, T.; Dias, N.V.; Sonesson, B.; Schermerhorn, M.L.; Lee, J.T.; et al. Multicenter study of retrograde open mesenteric artery stenting through laparotomy for treatment of acute and chronic mesenteric ischemia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 68, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, E.; Mascia, D.; Campesi, C.; Pizzutilli, A.C.; Melissano, G. Endovascular repair for acute aortic syndrome involving the descending aorta. Vessel Plus 2024, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donas, K.P.; Lee, J.T.; Lachat, M.; Torsello, G.; Veith, F.J.; PERICLES Investigators. Collected world experience about the performance of the snorkel/chimney endovascular technique in the treatment of complex aortic pathologies: The PERICLES registry. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Jabr, A.; Sonesson, B.; Lindblad, B.; Dias, N.; Resch, T.; Malina, M. Chimney grafts preserve visceral flow and allow safe stenting of juxtarenal aortic occlusion. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 57, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogendoorn, W.; Schlösser, F.J.V.; Moll, F.L.; Sumpio, B.E.; Muhs, B.E. Thoracic endovascular aortic repair with the chimney graft technique. J. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 58, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, F.; Veith, F.J.; Puippe, G.; Amman-Vesti, B.; Bettex, D.; Rancic, Z.; Pfammatter, T.; Lachat, M. Mid- and longer-term follow-up of chimney and/or periscope grafts and risk factors for failure. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2016, 51, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneva, G.T.; Lee, J.T.; Tran, K.; Dalman, R.; Torsello, G.; Fazzini, S.; Veith, F.J.; Donas, K.P. Long-term chimney/snorkel endovascular aortic aneurysm repair experience for complex abdominal aortic pathologies within the PERICLES registry. J. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.S.; Nguyen, S.; Lee, M.T.; Price, M.D.; Krause, H.; Truong, V.T.T.; Sandhu, H.K.; Charlton-Ouw, K.M.; LeMaire, S.A.; Coselli, J.S.; et al. Clinical characteristics and long-term outcomes of midaortic syndrome. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 66, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Pan, T.; Chen, B.; Jiang, J.; Fu, W.; Dong, Z. Long-term outcomes of surgical or endovascular treatment of adults with midaortic syndrome: A single-center retrospective study over a 14-year period. JTCVS Open 2024, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musajee, M.; Gasparini, M.; Stewart, D.J.; Karunanithy, N.; Sinha, M.D.; Sallam, M. Middle aortic syndrome in children and adolescents. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2022, 2022, e202220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xue, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, T.; Fang, K.; Luo, M.; Li, X.; He, H.; et al. Outcomes of thoracic endovascular aortic repair with chimney technique for aortic arch diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 868457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhang, X.; Fang, K.; Guo, Y.Y.; Chen, D.; Lee, J.T.; Shu, C. Endovascular aortic arch repair with chimney technique for pseudoaneurysm. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriani, S.; Erriyanti, S.; Dewangga, R.; Adiarto, S.; Siddiq, T.; Dakota, I. Late presentation of middle aortic syndrome complicated with severe aortic regurgitation: The role of endovascular intervention as a bridging for Bentall surgery. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2021, 8, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igari, K.; Kudo, T.; Toyofuku, T.; Inoue, Y. Outcomes of endovascular aneurysm repair with the chimney technique for juxtarenal aortic aneurysms. Ann. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2016, 22, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatanovic, P.; Jovanovic, A.; Tripodi, P.; Davidovic, L. Chimney vs. fenestrated endovascular vs. open repair for juxta/pararenal abdominal aortic aneurysms: Systematic review and network meta-analysis of medium-term results. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulakakis, K.G.; Mylonas, S.N.; Avgerinos, E.; Papapetrou, A.; Kakisis, J.D.; Brountzos, E.N.; Liapis, C.D. The chimney graft technique for preserving visceral vessels during endovascular treatment of aortic pathologies. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 55, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H. Endovascular chimney technique for aortic arch pathologies treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 47, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, R.; Stachowski, L.; Puippe, G.; Zimmermann, A.; Menges, A.-L. Long-Term Outcomes of Endovascular Aortic Repair with Parallel Chimney or Periscope Stent Grafts for Ruptured Complex Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapassaro, T.; Teraa, M.; Chinsakchai, K.; Hazenberg, C.E.V.B.; Hunnangkul, S.; Moll, F.L.; van Herwaarden, J.A. Mid-Term Outcomes of Chimney Endovascular Aortic Aneurysm Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 79, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Morikage, N.; Sakamoto, R.; Otsuka, R.; Ike, S.; Mizoguchi, T.; Samura, M.; Harada, T.; Kurazumi, H.; Suzuki, R.; et al. Early and Midterm Outcomes of Chimney Endovascular Aortic Repair for Ruptured Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, W.; Mylonas, S.; Majd, P.; Brunkwall, J.S. A current systematic evaluation and meta-analysis of chimney graft technology in aortic arch diseases. J. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 66, 1602–1610.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (A) | |

| Variable | Values |

| Sex (M/F) | 3/6 |

| Mean age (years) | 77.2 (range 68–89) |

| History of the ICA stent | 3/9 (33.3%) |

| ASA class | III in all patients |

| Smoking history | 5/9 (55.5%) |

| Comorbidities | CAD: 9/9 (100%); COPD: 1(11.11); Chronic renal failure: 7/9 (77.7%); HTN: 9/9 (100%); PAD: 9/9 (100%); CHF: 7/9 (77.7%); Diabetes mellitus: 4/9 (44.4%) |

| (B) | |

| Variable | Values |

| Chimney procedure performed | 9 (100%) |

| With Femoral endarterectomy | 3/9 (33.3%) |

| Preoperative Angiography | 6/9 (66.6%) |

| Mean operative time | 73.4 min (range 55–92) |

| Mean radiation time | 19.8 min (range 12–30) |

| Access route: | |

| 1-Percutan (Femoral and Transaxillary) | 5/9 (55.5%); |

| 2-Percutan (only Femoral) | 3/9 (33.3%); |

| 3-Open Surgical (Femoral and Transaxillary) | 5/9 (55.5%) |

| Wound infection | 0/9 (0%) |

| Length of hospital stay | Median 6 days (range 4–34) |

| Renal function improvement (> 30% GFR) | 4/9 (44.4%) |

| Complications | Pulmonary: 1; Cardiac: 0; Bleeding: 1; Gastrointestinal: 0 |

| Post-op medication | Dual antiplatelets: 9/9 (100%); Antihyperlipidemics: 9/9 (100%) |

| Ischemic complications | Spinal cord ischemia: 0; Bowel ischemia: 0 |

| Follow-up | Median 3 years (range 1 month–6 years) |

| Outcome | Result |

|---|---|

| Median follow-up (Years) | 3 years (range 1 month–6 years) |

| Target vessel patency | 100% |

| Renal impairment | None |

| Blood pressure control | Improved in all patients |

| Survival at follow-up | 100% |

| 30-day reintervention | 0/9 (0%) |

| 30-day mortality | 0/9 (0%) |

| (A) | |||

| Study/Year | Patient Cohort | Technique | Target-Vessel/Branch Patency/Freedom from Loss of Patency/Reintervention-Free Survival |

| Present study (n = 9) | n = 9; MAS with renal/visceral involvement | Chimney | 100% Target-Vessel Patency |

| Musajee et al. (2022) [22] | NA, Pediatric MAS | Open, endovascular (balloon/stent) | freedom from reintervention ~ 72% at 10 years |

| Patel et al. (2020) [20] | n = 13; Adult MAS | Open and endovascular | emphasizes multiple interventions and heterogeneity |

| Liu et al. (2024) [21] | n = 41; Adult MAS | Open and endovascular | Reintervention-free survival: open 87.7% at 5 yr, 71.7% at 10 yr; endovascular 92.3% at 5 yr, 79.1% at 10 yr |

| (B) | |||

| Study/Year | Patient Cohort | Technique | Target-Vessel/Branch Patency/Freedom from Loss of Patency/Reintervention-Free Survival |

| Bin Jabr et al. (2013) [16] | n =10; juxtarenal aortic stenosis/occlusion | Chimney | 100% Target-Vessel Patency up to 6 years in survivors. |

| Hogendoorn et al. (2013) [17] | n = 94; complex aortic disease, | TEVAR with chimney grafts | 100% Vessel Patency at median follow-up (11 months). |

| Donas et al. (2015) [15] | n = 517; complex aortic pathologies | Snorkel/chimney (ch-EVAR) | Primary patency 94% at 17.1 months (secondary patency 95.3%). |

| Taneva et al. (2021) [19] | n = 517; branches; complex AAA | chEVAR | 92% chimney branch patency |

| Li et al. (2022) [23] | n = 345; arch pathologies | Chimney-TEVAR | Primary and assisted chimney patency ~97% |

| Luo et al. (2023) [24] | n = 32; aortic arch repair | Chimney | 100% branch patency at mid-term |

| Verlato et al. (2024) [12] | n = 51; complex AAA (juxta/pararenal) | chEVAR (parallel grafts) | Freedom from type Ia endoleak 91.8% at 7 years |

| Indriani (2021) [25] | One Patient | Endovascular covered stent or hybrid | Successful short-term improvement in BP and symptoms after stenting; adds to the evidence base for endovascular options in select adults. |

| Igari et al. (2016) [26] | n = 12 | Ch-EVAR | Technical success 91.6%; the target vessel patency rate was 93.3% |

| Zlatanovic et al. (2022) [27] | Several studies pooled | chEVAR vs FEVAR vs open | Medium-term outcomes for chEVAR are comparable when FEVAR is unavailable; endoleak and reintervention rates are higher in some analyses. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Algedaiby, H.; Fattoum, M.; Keese, M. Feasibility and Early and Midterm Outcomes of Midaortic Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010036

Algedaiby H, Fattoum M, Keese M. Feasibility and Early and Midterm Outcomes of Midaortic Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010036

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlgedaiby, Hamad, Maher Fattoum, and Michael Keese. 2026. "Feasibility and Early and Midterm Outcomes of Midaortic Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010036

APA StyleAlgedaiby, H., Fattoum, M., & Keese, M. (2026). Feasibility and Early and Midterm Outcomes of Midaortic Syndrome: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010036