Locoregional Breast Cancer Recurrences After Ablatio Mammae and Primary Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Cohort

2.2. Patient Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Mastectomy without primary reconstruction

- Mastectomy with primary autologous reconstruction

- Mastectomy with primary allogeneic reconstruction

- Mastectomy with combined primary autologous and allogeneic reconstruction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Characteristics

3.2. Patient and Tumor Characteristics

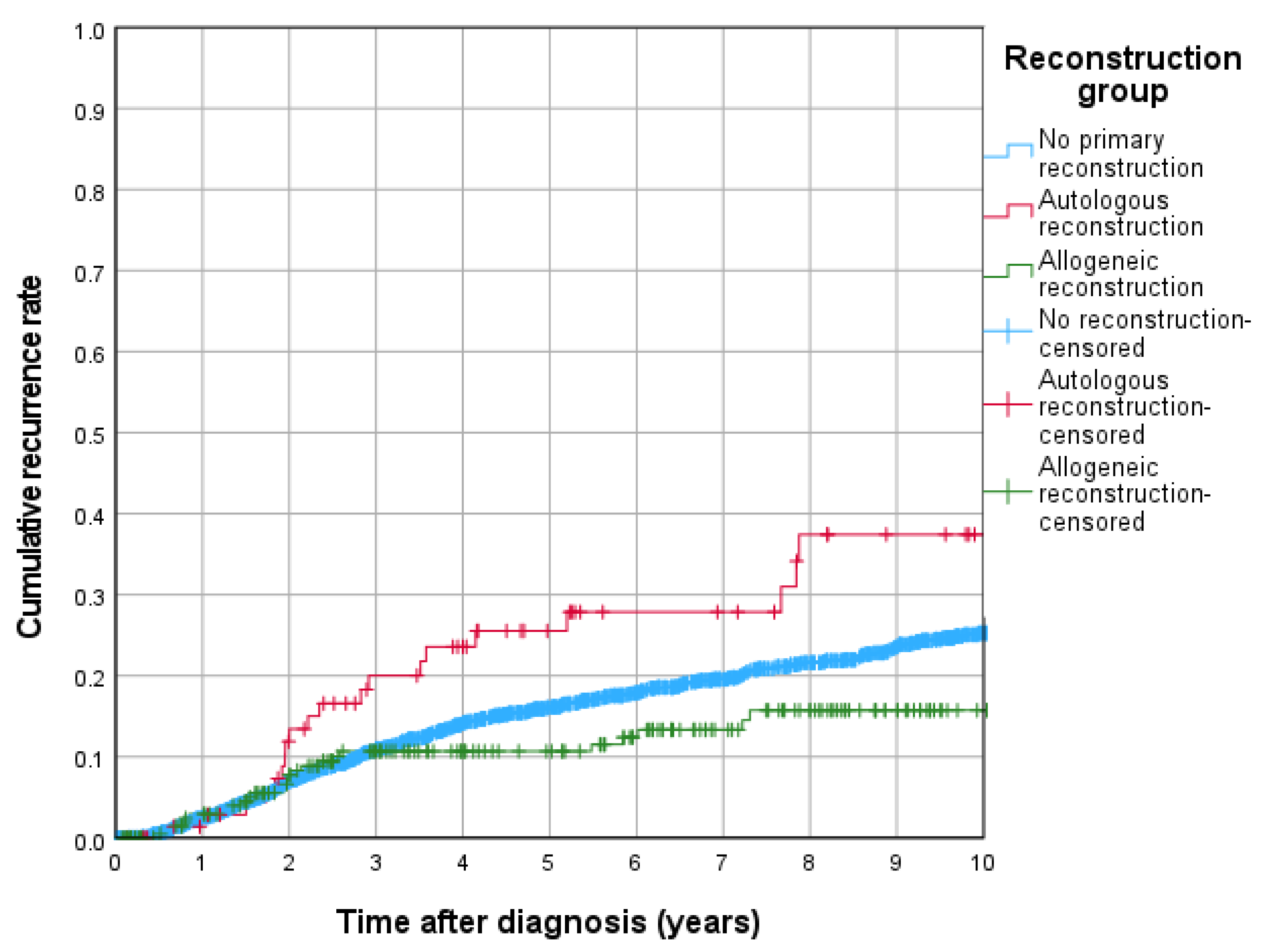

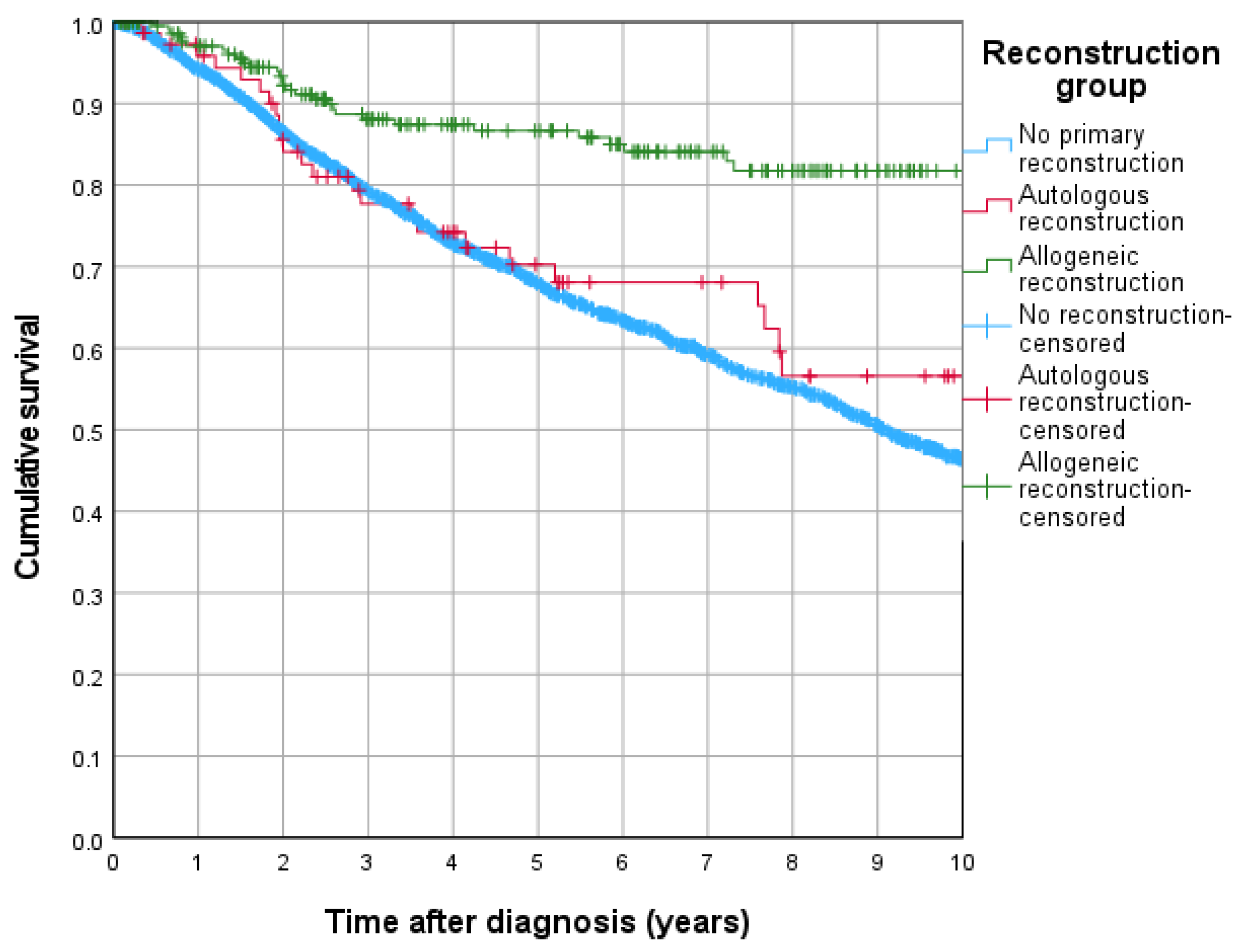

3.3. Cumulative Recurrence, 5-Year Overall Survival and Recurrence-Free Survival

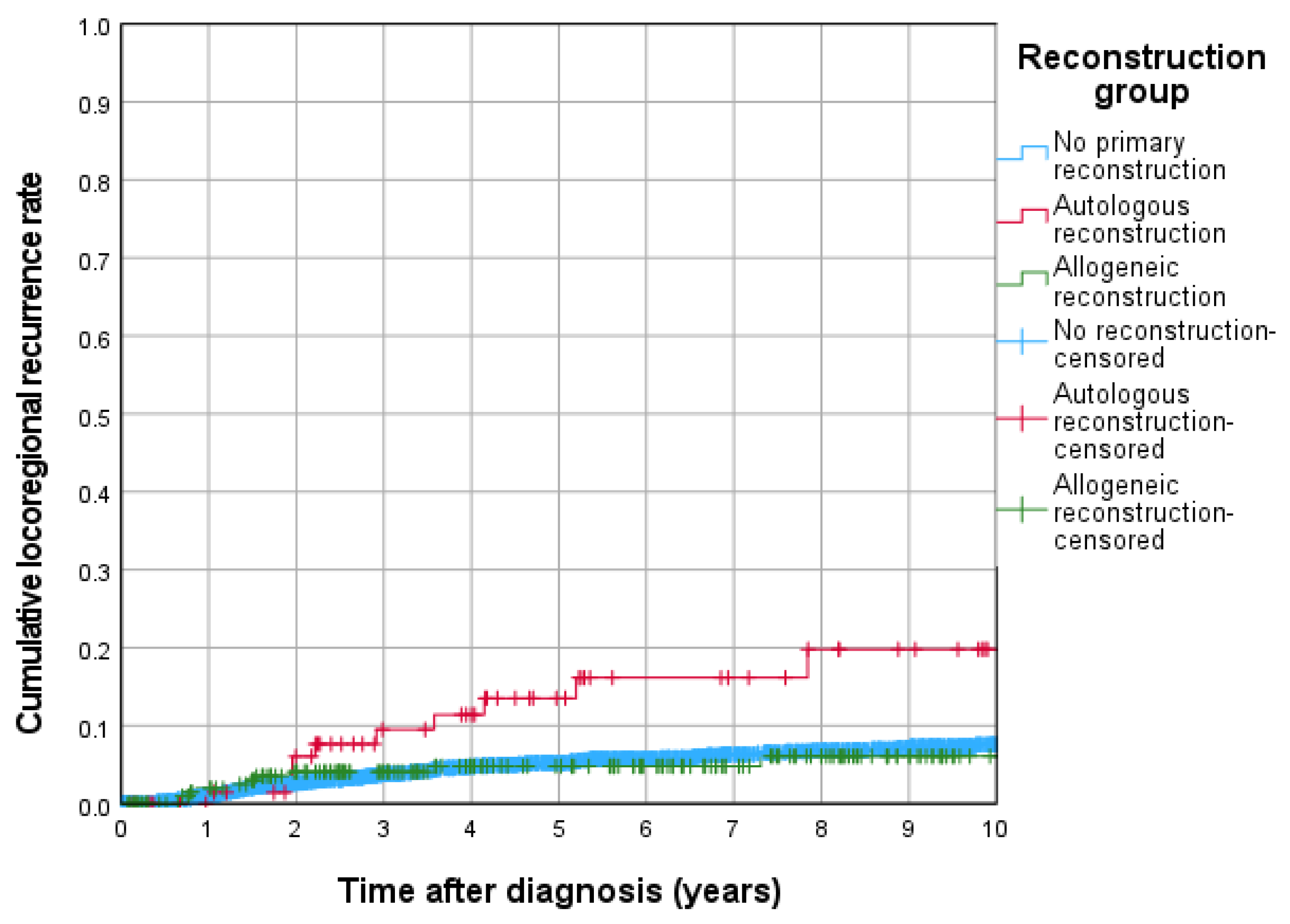

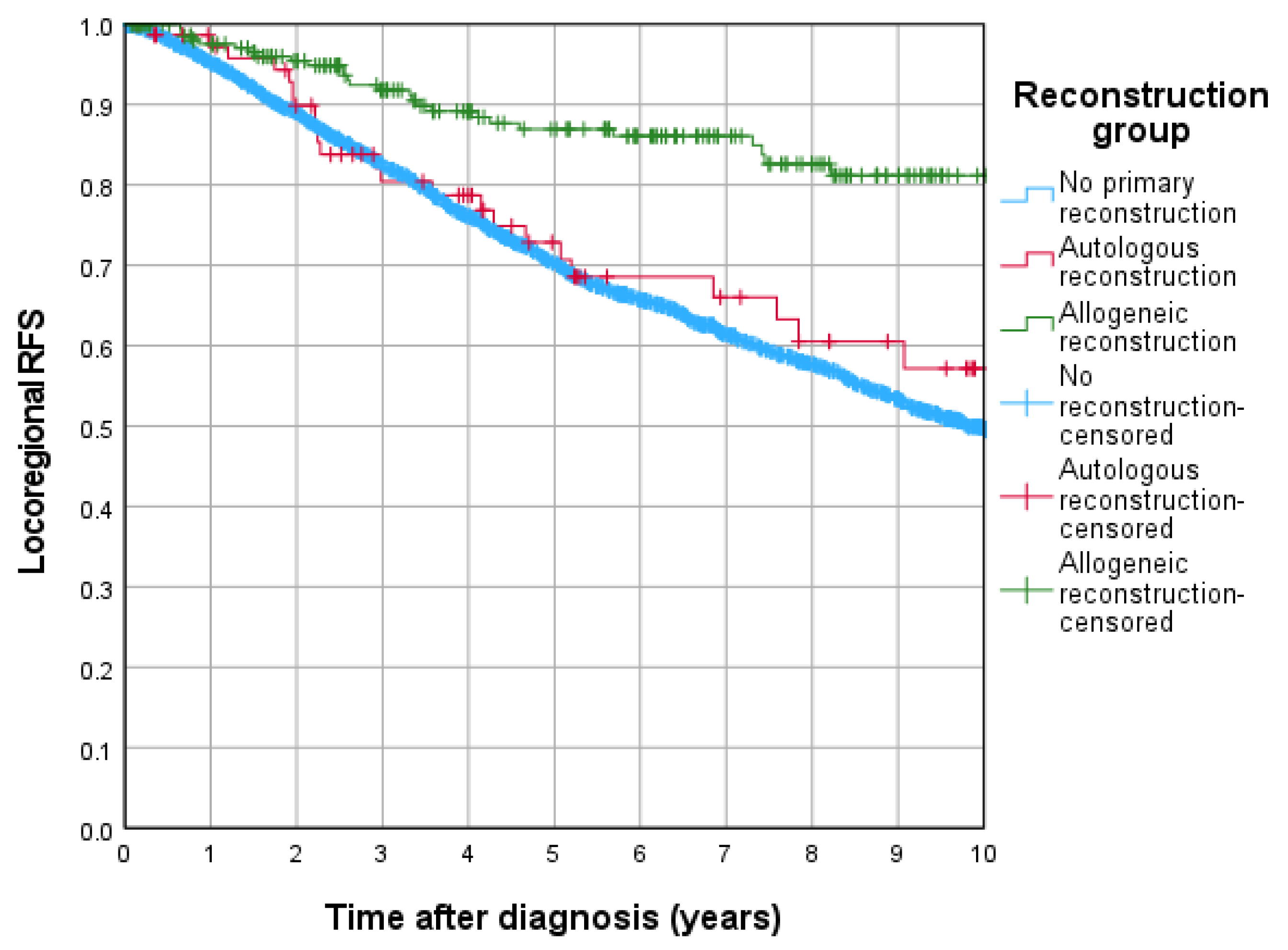

3.4. Cumulative Locoregional Recurrence and Locoregional Recurrence Free Survival

3.5. Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCT | Breast conserving therapy |

| DIEP | Deep inferior epigastric perforator |

| LRR | Locoregional recurrence rate |

| OS | Overall survival |

| RFS | Recurrence-free survival |

| CRR | Cumulative recurrence rate |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| EC | Endothelial cell |

| BIA-ALCL | Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/DE/Content/Publikationen/Krebs_in_Deutschland/kid_2023/kid_2023_c50_brust.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Ignatiadis, M.; Sotiriou, C. Luminal breast cancer: From biology to treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; He, J.-J.; Tang, X.-J. Associations between clinical-pathological parameters and biomarkers, HER-2, TYMS, RRMI, and 21-gene recurrence score in breast cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.; Strom, E.A.; Buchholz, T.A.; Theriault, R.; Singletary, S.E.; McNeese, M.D. The influence of pathologic tumor characteristics on locoregional recurrence rates following mastectomy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2001, 50, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, P.T.; Jones, S.O.; Kader, H.A.; Wai, E.S.; Speers, C.H.; Alexander, A.S.; Olivotto, I.A. Patients with t1 to t2 breast cancer with one to three positive nodes have higher local and regional recurrence risks compared with node-negative patients after breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009, 73, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.F.; Gray, R.; Dressler, L.G.; Cobau, C.D.; Falkson, C.I.; Gilchrist, K.W.; Pandya, K.J.; Page, D.L.; Robert, N.J. Prognostic value of histologic grade and proliferative activity in axillary node-positive breast cancer: Results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Companion Study, EST 4189. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 2059–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehinger, A.; Malmström, P.; Bendahl, P.-O.; Elston, C.W.; Falck, A.-K.; Forsare, C.; Grabau, D.; Rydén, L.; Stål, O.; Fernö, M.; et al. Histological grade provides significant prognostic information in addition to breast cancer subtypes defined according to St Gallen 2013. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilchrist, K.W.; Gray, R.; Fowble, B.; Tormey, D.C.; Taylor, S.G. Tumor necrosis is a prognostic predictor for early recurrence and death in lymph node-positive breast cancer: A 10-year follow-up study of 728 Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 1993, 11, 1929–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, R.A.; He, Y.; Winer, E.P.; Keating, N.L. Trends in racial and age disparities in definitive local therapy of early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, T.S.; Bosco, J.L.F.; Prout, M.N.; Gold, H.T.; Cutrona, S.; Pawloski, P.A.; Ulcickas Yood, M.; Quinn, V.P.; Thwin, S.S.; Silliman, R.A. Age, comorbidity, and breast cancer severity: Impact on receipt of definitive local therapy and rate of recurrence among older women with early-stage breast cancer. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011, 213, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wöckel, A.; Festl, J.; Stüber, T.; Brust, K.; Stangl, S.; Heuschmann, P.U.; Albert, U.-S.; Budach, W.; Follmann, M.; Janni, W.; et al. Interdisciplinary Screening, Diagnosis, Therapy and Follow-up of Breast Cancer. Guideline of the DGGG and the DKG (S3-Level, AWMF Registry Number 032/045OL, December 2017)—Part 1 with Recommendations for the Screening, Diagnosis and Therapy of Breast Cancer. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2018, 78, 927–948. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, C.S. Increasing Role of Oncoplastic Surgery for Breast Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.A. Radical mastectomy with en bloc in continuity resection of the internal mammary lymph-node chain. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 1958, 8, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunnick, G.H.; Mokbel, K. Skin-sparing mastectomy. Am. J. Surg. 2004, 188, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ghazal, S.K.; Sully, L.; Fallowfield, L.; Blamey, R.W. The psychological impact of immediate rather than delayed breast reconstruction. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2000, 26, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, C.; Allen, R.J. The evolution of perforator flap breast reconstruction: Twenty years after the first DIEP flap. J. Reconstr. Microsurg. 2014, 30, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steiner, D.; Horch, R.E.; Ludolph, I.; Schmitz, M.; Beier, J.P.; Arkudas, A. Interdisciplinary Treatment of Breast Cancer After Mastectomy with Autologous Breast Reconstruction Using Abdominal Free Flaps in a University Teaching Hospital-A Standardized and Safe Procedure. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahabedian, M.Y.; Tsangaris, T.; Momen, B. Breast reconstruction with the DIEP flap or the muscle-sparing (MS-2) free TRAM flap: Is there a difference? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 115, 436–444; discussion 445–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitgasser, L.; Schwaiger, K.; Medved, F.; Hamler, F.; Wechselberger, G.; Schoeller, T. Bilateral Simultaneous Breast Reconstruction with DIEP- and TMG Flaps: Head to Head Comparison, Risk and Complication Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, A.M.; Prantl, L.; Strauss, C.; Brébant, V.; Baringer, M.; Ruewe, M.; Vykoukal, J.; Klein, S.M. Clinical Impact of DIEP Flap Perforator Characteristics—A Prospective Indocyanine Green Fluorescence Imaging Study. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2020, 73, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, M.; Sowa, Y.; Tsuge, I.; Kodama, T.; Inafuku, N.; Morimoto, N. Long-Term Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life Following Breast Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q: A Prospective Cohort Study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 815498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakha, E.A.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; Baehner, F.; Dabbs, D.J.; Decker, T.; Eusebi, V.; Fox, S.B.; Ichihara, S.; Jacquemier, J.; Lakhani, S.R.; et al. Breast cancer prognostic classification in the molecular era: The role of histological grade. Breast Cancer Res. 2010, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotiriou, C.; Wirapati, P.; Loi, S.; Harris, A.; Fox, S.; Smeds, J.; Nordgren, H.; Farmer, P.; Praz, V.; Haibe-Kains, B.; et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: Understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voduc, K.D.; Cheang, M.C.U.; Tyldesley, S.; Gelmon, K.; Nielsen, T.O.; Kennecke, H. Breast cancer subtypes and the risk of local and regional relapse. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallgren, A.; Bonetti, M.; Gelber, R.D.; Goldhirsch, A.; Castiglione-Gertsch, M.; Holmberg, S.B.; Lindtner, J.; Thürlimann, B.; Fey, M.; Werner, I.D.; et al. Risk factors for locoregional recurrence among breast cancer patients: Results from International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I through VII. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagsi, R.; Raad, R.A.; Goldberg, S.; Sullivan, T.; Michaelson, J.; Powell, S.N.; Taghian, A.G. Locoregional recurrence rates and prognostic factors for failure in node-negative patients treated with mastectomy: Implications for postmastectomy radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2005, 62, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rack, B.; Janni, W.; Gerber, B.; Strobl, B.; Schindlbeck, C.; Klanner, E.; Rammel, G.; Sommer, H.; Dimpfl, T.; Friese, K. Patients with recurrent breast cancer: Does the primary axillary lymph node status predict more aggressive tumor progression? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2003, 82, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanter, J.; Zimmerman, B.; Tharakan, S.; Ru, M.; Cascetta, K.; Tiersten, A. BRCA Mutation Association with Recurrence Score and Discordance in a Large Oncotype Database. Oncology 2020, 98, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, H.A.; Michiels, S.; Bedard, P.L.; Singhal, S.K.; Criscitiello, C.; Ignatiadis, M.; Haibe-Kains, B.; Piccart, M.J.; Sotiriou, C.; Loi, S. Elucidating prognosis and biology of breast cancer arising in young women using gene expression profiling. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loibl, S.; Jackisch, C.; Lederer, B.; Untch, M.; Paepke, S.; Kümmel, S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Huober, J.; Hilfrich, J.; Hanusch, C.; et al. Outcome after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in young breast cancer patients: A pooled analysis of individual patient data from eight prospectively randomized controlled trials. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 152, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwald, E.C.; Klinkhammer-Schalke, M.; Hofstädter, F.; Zeman, F.; Koller, M.; Gerstenhauer, M.; Ortmann, O. Ki-67 is a prognostic parameter in breast cancer patients: Results of a large population-based cohort of a cancer registry. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 139, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group; Nielsen, H.M.; Overgaard, M.; Grau, C.; Jensen, A.R.; Overgaard, J. Study of failure pattern among high-risk breast cancer patients with or without postmastectomy radiotherapy in addition to adjuvant systemic therapy: Long-term results from the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group DBCG 82 b and c randomized studies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 2268–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Morley, T.S.; Kim, M.; Clegg, D.J.; Scherer, P.E. Obesity and cancer--mechanisms underlying tumour progression and recurrence. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demicheli, R.; Retsky, M.W.; Hrushesky, W.J.M.; Baum, M.; Gukas, I.D. The effects of surgery on tumor growth: A century of investigations. Ann. Oncol. 2008, 19, 1821–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demicheli, R.; Dillekås, H.; Straume, O.; Biganzoli, E. Distant metastasis dynamics following subsequent surgeries after primary breast cancer removal. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreklau, A.; Nel, I.; Kasimir-Bauer, S.; Kimmig, R.; Frackenpohl, A.C.; Aktas, B. An Observational Study on Breast Cancer Survival and Lifestyle Related Risk Factors. In Vivo 2021, 35, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.A.; Goyal, A.; Terry, M.B. Alcohol Intake and Breast Cancer Risk: Weighing the Overall Evidence. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2013, 5, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, N.; Sekino, Y.; Kanda, Y. Nicotine increases cancer stem cell population in MCF-7 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 403, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Hirata, N.; Sekino, Y.; Kanda, Y. Role of α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in normal and cancer stem cells. Curr. Drug Targets 2012, 13, 656–665. [Google Scholar]

- Jordahl, K.M.; Malone, K.E.; Baglia, M.L.; Flanagan, M.R.; Tang, M.-T.C.; Porter, P.L.; Li, C.I. Alcohol consumption, smoking, and invasive breast cancer risk after ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 193, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starek-Świechowicz, B.; Budziszewska, B.; Starek, A. Alcohol and breast cancer. Pharmacol. Rep. 2023, 75, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshirian, A.; Heydari, K.; Shams, Z.; Aref, A.R.; Shamshirian, D.; Tamtaji, O.R.; Asemi, Z.; Shojaie, L.; Mirzaei, H.; Mohammadi, N.; et al. Breast cancer risk factors in Iran: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2020, 41, 20200021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picon-Ruiz, M.; Morata-Tarifa, C.; Valle-Goffin, J.J.; Friedman, E.R.; Slingerland, J.M. Obesity and adverse breast cancer risk and outcome: Mechanistic insights and strategies for intervention. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 378–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, P.; Winn, M.; Pauleck, S.; Bulsiewicz-Jacobsen, A.; Peterson, L.; Coletta, A.; Doherty, J.; Ulrich, C.M.; Summers, S.A.; Gunter, M.; et al. Metabolic dysfunction and obesity-related cancer: Beyond obesity and metabolic syndrome. Obesity 2022, 30, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoramdad, M.; Solaymani-Dodaran, M.; Kabir, A.; Ghahremanzadeh, N.; Hashemi, E.-O.-S.; Fahimfar, N.; Omidi, Z.; Mansournia, M.A.; Olfatbakh, A.; Salehiniya, H.; et al. Breast cancer risk factors in Iranian women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of matched case-control studies. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2022, 27, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta-Guirado, B.I.; González-Rocha, A.; Mérida-Ortega, Á.; López-Carrillo, L.; Denova-Gutiérrez, E. Lifestyle Quality Indices and Female Breast Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 685–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettini, F.; Pascual, T.; Conte, B.; Chic, N.; Brasó-Maristany, F.; Galván, P.; Martínez, O.; Adamo, B.; Vidal, M.; Muñoz, M.; et al. HER2-enriched subtype and pathological complete response in HER2-positive breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 84, 101965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ades, F.; Zardavas, D.; Bozovic-Spasojevic, I.; Pugliano, L.; Fumagalli, D.; de Azambuja, E.; Viale, G.; Sotiriou, C.; Piccart, M. Luminal B Breast Cancer: Molecular Characterization, Clinical Management, and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2794–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, M.; Demicheli, R.; Hrushesky, W.; Retsky, M. Does surgery unfavourably perturb the “natural history” of early breast cancer by accelerating the appearance of distant metastases? Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krastev, T.K.; Schop, S.J.; Hommes, J.; Piatkowski, A.A.; Heuts, E.M.; van der Hulst, R.R.W.J. Meta-analysis of the oncological safety of autologous fat transfer after breast cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 1082–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongu, T.; Pein, M.; Insua-Rodríguez, J.; Gutjahr, E.; Mattavelli, G.; Meier, J.; Decker, K.; Descot, A.; Bozza, M.; Harbottle, R.; et al. Perivascular tenascin C triggers sequential activation of macrophages and endothelial cells to generate a pro-metastatic vascular niche in the lungs. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demicheli, R.; Bonadonna, G.; Hrushesky, W.J.; Retsky, M.W.; Valagussa, P. Menopausal status dependence of the timing of breast cancer recurrence after surgical removal of the primary tumour. Breast Cancer Res. 2004, 6, R689–R696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deva, A.K.; Turner, S.D.; Kadin, M.E.; Magnusson, M.R.; Prince, H.M.; Miranda, R.N.; Inghirami, G.G.; Adams, W.P. Etiology of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL): Current Directions in Research. Cancers 2020, 12, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mempin, M.; Hu, H.; Vickery, K.; Kadin, M.E.; Prince, H.M.; Kouttab, N.; Morgan, J.W.; Adams, W.P.; Deva, A.K. Gram-Negative Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide Promotes Tumor Cell Proliferation in Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large-Cell Lymphoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liewald, F.; Wirsching, R.P.; Zülke, C.; Demmel, N.; Mempel, W. Influence of blood transfusions on tumor recurrence and survival rate in colorectal carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 1990, 26, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reconstruction Group | Total n | n of Events |

|---|---|---|

| No reconstruction | 2156 | 373 |

| Autologous reconstruction | 76 | 20 |

| Allogeneic reconstruction | 222 | 26 |

| Overall | 2475 | 421 |

| Univariable Cox-Regression | Multivariable Cox-Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | HR | Lower Bound 95%-CI | Upper Bound 95%-CI | p | HR | Lower Bound 95%-CI | Upper Bound 95%-CI | |

| Overall survival | ||||||||

| No primary reconstruction | <0.001 | Ref. | 0.050 | Ref. | ||||

| Autologous reconstruction | 0.078 | 0.664 | 0.421 | 1.046 | 0.133 | 1.437 | 0.895 | 2.306 |

| Allogeneic reconstruction | <0.001 | 0.258 | 0.168 | 0.398 | 0.015 | 0.570 | 0.363 | 0.896 |

| Recurrence free survival | ||||||||

| No primary reconstruction | <0.001 | Ref. | 0.010 | Ref. | ||||

| Autologous reconstruction | 0.482 | 0.870 | 0.589 | 1.284 | 0.012 | 1.690 | 1.124 | 2.541 |

| Allogeneic reconstruction | <0.001 | 0.335 | 0.233 | 0.482 | 0.039 | 0.669 | 0.457 | 0.980 |

| Cumulative recurrence rate (total) | ||||||||

| No primary reconstruction | 0.061 | Ref. | 0.016 | Ref. | ||||

| Autologous reconstruction | 0.032 | 1.637 | 1.044 | 2.568 | 0.002 | 2.156 | 1.333 | 3.486 |

| Allogeneic reconstruction | 0.099 | 0.716 | 0.481 | 1.065 | 0.583 | 0.889 | 0.585 | 1.353 |

| Cumulative locoregional recurrence rate | ||||||||

| No primary reconstruction | 0.054 | Ref. | 0.035 | Ref. | ||||

| Autologous reconstruction | 0.003 | 2.633 | 1.379 | 5.028 | 0.003 | 3.016 | 1.472 | 6.178 |

| Allogeneic reconstruction | 0.992 | 0.997 | 0.537 | 1.851 | 0.701 | 1.143 | 0.577 | 2.265 |

| Cumulative metastatic recurrence rate | ||||||||

| No primary reconstruction | 0.224 | Ref. | 0.101 | Ref. | ||||

| Autologous reconstruction | 0.076 | 1.602 | 0.952 | 2.693 | 0.010 | 2.070 | 1.187 | 3.610 |

| Allogeneic reconstruction | 0.196 | 0.741 | 0.471 | 1.167 | 0.663 | 0.900 | 0.559 | 1.449 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Valette, C.; Anker, A.; Gerken, M.; Seitz, S.; Klinkhammer-Schalke, M.; Eisenmann, S.; Ruewe, M.; Unbehaun, P.; Prantl, L.; Brébant, V. Locoregional Breast Cancer Recurrences After Ablatio Mammae and Primary Reconstruction. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010326

Valette C, Anker A, Gerken M, Seitz S, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, Eisenmann S, Ruewe M, Unbehaun P, Prantl L, Brébant V. Locoregional Breast Cancer Recurrences After Ablatio Mammae and Primary Reconstruction. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010326

Chicago/Turabian StyleValette, Constance, Alexandra Anker, Michael Gerken, Stephan Seitz, Monika Klinkhammer-Schalke, Silvan Eisenmann, Marc Ruewe, Philipp Unbehaun, Lukas Prantl, and Vanessa Brébant. 2026. "Locoregional Breast Cancer Recurrences After Ablatio Mammae and Primary Reconstruction" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010326

APA StyleValette, C., Anker, A., Gerken, M., Seitz, S., Klinkhammer-Schalke, M., Eisenmann, S., Ruewe, M., Unbehaun, P., Prantl, L., & Brébant, V. (2026). Locoregional Breast Cancer Recurrences After Ablatio Mammae and Primary Reconstruction. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010326