Prediction and Risk Evaluation for Surgical Intervention in Small Bowel Obstruction † †

Abstract

1. Introduction

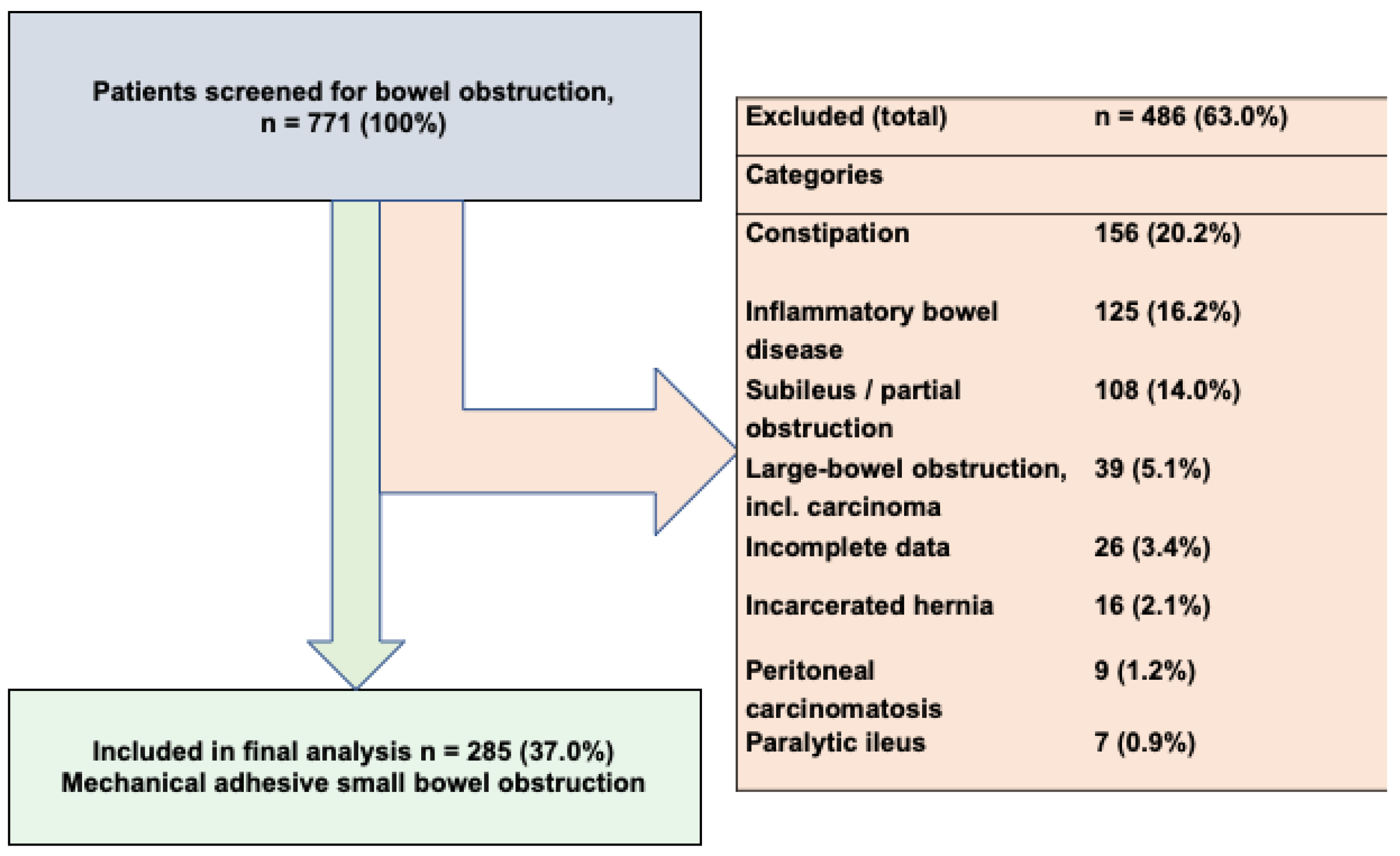

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Algorithm for SBO Management

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

3.2. Surgical Characteristics

3.3. Conservative Treatment Group

3.4. Predictors of Surgical Intervention

3.5. Risk Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SBO | Small Bowel Obstruction |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

References

- Li, R.; Quintana, M.T.; Lee, J.; Sarani, B.; Kartiko, S. Timing to surgery in elderly patients with small bowel obstruction: An insight on frailty. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2024, 97, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami Reddy, S.R.; Cappell, M.S. A Systematic Review of the Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Small Bowel Obstruction. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2017, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.T. (Ed.) Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie Essentials: Intensivkurs zur Weiterbildung [Internet], 8th ed.; Georg Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; p. b-004-132233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.R.; Lalani, N. Adult Small Bowel Obstruction. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2013, 20, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detz, D.J.; Podrat, J.L.; Muniz Castro, J.C.; Lee, Y.K.; Zheng, F.; Purnell, S.; Pei, K.Y. Small bowel obstruction. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2021, 58, 100893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftus, T.; Moore, F.; VanZant, E.; Bala, T.; Brakenridge, S.; Croft, C.; Lottenberg, L.; Richards, W.; Mozingo, D.; Atteberry, L.; et al. A protocol for the management of adhesive small bowel obstruction. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015, 78, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoufalia, Z.; Gefen, R.; Emile, S.H.; Zhou, P.; Silva-Alvarenga, E.; Wexner, S.D. Financial and Inpatient Burden of Adhesion-Related Small Bowel Obstruction: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Broek, R.P.G.; Krielen, P.; Di Saverio, S.; Coccolini, F.; Biffl, W.L.; Ansaloni, L.; Velmahos, G.C.; Sartelli, M.; Fraga, G.P.; Kelly, M.D.; et al. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2017 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world society of emergency surgery ASBO working group. World J. Emerg. Surg. WJES 2018, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maienza, E.; Godiris-Petit, G.; Noullet, S.; Menegaux, F.; Chereau, N. Management of adhesive small bowel obstruction: The results of a large retrospective study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2023, 38, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.G.; Karamanos, E.; Talving, P.; Inaba, K.; Lam, L.; Demetriades, D. Early operation is associated with a survival benefit for patients with adhesive bowel obstruction. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghabisha, S.; Ahmed, F.; Altam, A.; Hassan, F.; Badheeb, M. Small Bowel Obstruction in Virgin Abdomen: Predictors of Surgical Intervention Need in Resource-Limited Setting. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 4003–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarr, M.G.; Bulkley, G.B.; Zuidema, G.D. Preoperative recognition of intestinal strangulation obstruction. Prospective evaluation of diagnostic capability. Am. J. Surg. 1983, 145, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraufnagel, D.; Rajaee, S.; Millham, F.H. How many sunsets? Timing of surgery in adhesive small bowel obstruction: A study of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 74, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fevang, B.T.; Fevang, J.M.; Søreide, O.; Svanes, K.; Viste, A. Delay in Operative Treatment among Patients with Small Bowel Obstruction. Scand. J. Surg. 2003, 92, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delabrousse, E.; Lubrano, J.; Jehl, J.; Morati, P.; Rouget, C.; Mantion, G.A.; Kastler, B.A. Small-bowel obstruction from adhesive bands and matted adhesions: CT differentiation. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2009, 192, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, K.; Szécsi, T.; Jirikowski, B. Intestinal obstruction caused by solitary bands: Aetiology, presentation, diagnosis, management, results. Acta Chir. Hung. 1994, 34, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, S.W.; Choi, Y.S. Laparoscopy for Small Bowel Obstruction Caused by Single Adhesive Band. J. Soc. Laparosc. Robot. Surg. 2016, 20, e2016.00048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, V.N.; Parry, T.; Boone, D.; Mallett, S.; Halligan, S. Prognostic factors to identify resolution of small bowel obstruction without need for operative management: Systematic review. Eur. Radiol. 2024, 34, 3861–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collom, M.L.; Duane, T.M.; Campbell-Furtick, M.; Moore, B.J.; Haddad, N.N.; Zielinski, M.D.; Ray-Zack, M.D.; Yeh, D.D. Deconstructing dogma: Nonoperative management of small bowel obstruction in the virgin abdomen. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018, 85, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A.G.; Hill, G.L. Metabolic response to severe injury. Br. J. Surg. 1998, 85, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.L.; Slutsky, A.S. Sepsis and endothelial permeability. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, A.; Hanna, M.H.; Moghadamyeghaneh, Z.; Stamos, M.J. Implications of preoperative hypoalbuminemia in colorectal surgery. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2016, 8, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naga Rohith, V.; Arya, S.V.; Rani, A.; Chejara, R.K.; Sharma, A.; Arora, J.K.; Kalwaniya, D.S.; Tolat, A.; G, P.; Singh, A. Preoperative Serum Albumin Level as a Predictor of Abdominal Wound-Related Complications After Emergency Exploratory Laparotomy. Cureus 2022, 14, e31980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Liu, H.; Tang, S.; Wu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Liu, W.; Qi, W.; Ye, L.; Cao, Q.; Zhou, W. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications in Crohn’s disease patients with normal BMI: A cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 79, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.-Q.; Zhang, K.-C.; Li, H.; Cui, J.-X.; Xi, H.-Q.; Li, J.-Y.; Cai, A.-Z.; Liu, Y.-H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. Preoperative albumin levels predict prolonged postoperative ileus in gastrointestinal surgery. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besler, E.; Teke, E.; Akkuş, D.; Demir, M.H.; Aksaray, S.; Aydın Aksu, S.; Gürleyik, M.G. A new risk scoring system for early prediction of surgical need in patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction: A single-center retrospective clinical study. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2023, 105, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, G.K.; Gulen, M.; Acehan, S.; Firat, B.T.; Isikber, C.; Kaya, A.; Segmen, M.S.; Simsek, Y.; Sozutek, A.; Satar, S. Do biomarkers have predictive value in the treatment modality of the patients diagnosed with bowel obstruction? Rev. Assoc. Medica. Bras. 2022, 68, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Park, I.S.; Kim, J.; Cho, H.J.; Gwak, G.H.; Yang, K.H.; Bae, B.N.; Kim, K.H. Factors Predicting the Need for Early Surgical Intervention for Small Bowel Obstruction. Ann. Coloproctology 2020, 36, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenter, F.; Poletti, P.A.; Platon, A.; Perneger, T.; Morel, P.; Gervaz, P. Clinicoradiological score for predicting the risk of strangulated small bowel obstruction. Br. J. Surg. 2010, 97, 1119–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, K.; Weber, E.; Andersson, R.; Tingstedt, B. Small bowel obstruction: Early parameters predicting the need for surgical intervention. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 2011, 37, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevikel, M.H.; Ozgün, H.; Boylu, S.; Demirkiran, A.E.; Aydin, N.; Sari, C.; Erkus, M. C-reactive protein may be a marker of bacterial translocation in experimental intestinal obstruction. ANZ J. Surg. 2004, 74, 900–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awady, S.I.; El-Nagar, M.; El-Dakar, M.; Ragab, M.; Elnady, G. Bacterial translocation in an experimental intestinal obstruction model. C-reactive protein reliability? Acta Cir. Bras. 2009, 24, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, M.D.; Eiken, P.W.; Bannon, M.P.; Heller, S.F.; Lohse, C.M.; Huebner, M.; Sarr, M.G. Small bowel obstruction-who needs an operation? A multivariate prediction model. World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavangari, F.R.; Batech, M.; Collins, J.C.; Tejirian, T. Small Bowel Obstructions in a Virgin Abdomen: Is an Operation Mandatory? Am. Surg. 2016, 82, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.Q.; Hsu, V.; Tee, W.W.H.; Tan, J.H.; Wijesuriya, R. Predictors for success of non-operative management of adhesive small bowel obstruction. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 1116–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldemir, M.; Yağnur, Y.; Taçyildir, I. The predictive factors for the necessity of operative treatment in adhesive small bowel obstruction cases. Acta Chir. Belg. 2004, 104, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, E.A.; Desale, S.Y.; Yi, W.S.; Fujita, K.A.; Hynes, C.F.; Chandra, S.K.; Sava, J.A. Letting the sun set on small bowel obstruction: Can a simple risk score tell us when nonoperative care is inappropriate? Am. Surg. 2014, 80, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrima, A.; Lubner, M.G.; King, S.; Pankratz, J.; Kennedy, G.; Pickhardt, P.J. Value of MDCT and Clinical and Laboratory Data for Predicting the Need for Surgical Intervention in Suspected Small-Bowel Obstruction. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 208, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All Patients (n = 285) | Operative Group (n = 234) | Conservative Group (n = 51) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 68 (23) | 67 (25.8) | 70 (17.5) | 0.212 |

| Age (>68 years), n (%) | 141 (49.5) | 110 (47.0) | 31 (60.8) | 0.075 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.362 | |||

| Female | 145 (50.9) | 122 (52.1) | 23 (45.1) | |

| Male | 140 (49.1) | 112 (47.9) | 28 (54.9) | |

| ASA, n (%) | 0.289 | |||

| I | 30 (10.5) | 27 (11.5) | 3 (5.9) | |

| II | 112 (39.3) | 92 (39.3) | 20 (39.2) | |

| III | 135 (47.4) | 107 (45.7) | 28 (54.9) | |

| IV | 8 (2.8) | 8 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ASA I–II vs. III–IV n, (%) | 0.456 | |||

| I/II | 142 (49.8) | 119 (50.9%) | 23 (45.1%) | |

| III/IV | 143 (50.2) | 115 (49.1) | 28 (54.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 25.3 (6.1) | 25.1 (6.5) | 25.3 (5.2) | 0.879 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.703 | |||

| >25 | 144 (50.5) | 117 (50.0) | 27 (52.9) | |

| ≤25 | 141 (49.5) | 117 (50.0) | 24 (47.1) | |

| Hospital stay (days), median (IQR) | 9 (8) | 10 (9) | 4 (3) | <0.001 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 143 (50.2) | 114 (48.7) | 29 (56.9) | 0.292 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 65 (22.8) | 53 (22.6) | 12 (23.5) | 0.892 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 34 (11.9) | 28 (12.0) | 6 (11.8) | 0.968 |

| Crohn’s disease, n (%) | 17 (6.0) | 14 (6.0) | 3 (5.9) | 0.978 |

| Ulcerative colitis, n (%) | 7 (2.5) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (7.8) | 0.006 |

| COPD, n (%) | 25 (8.8) | 20 (8.5) | 5 (9.8) | 0.774 |

| Number of previous surgeries, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 or 1 previous surgery | 135 (47.4) | 123 (52.6) | 12 (23.5) | |

| >1 previuous surgery | 150 (52.6) | 111 (47.4) | 39 (76.5) | |

| Type of previous surgery, n (%) | ||||

| Appendectomy | 115 (40.4) | 81 (34.6) | 34 (66.7) | <0.001 |

| Colon resections | 52 (18.2) | 46 (19.7) | 6 (11.8) | 0.186 |

| Gynecological surgery | 31 (10.9) | 24 (10.3) | 7 (13.7) | 0.461 |

| Ileus operation | 53 (18.6) | 34 (14.5) | 19 (37.3) | <0.001 |

| Urological surgery | 53 (18.6) | 34 (14.5) | 19 (37.3) | <0.001 |

| Blood results | ||||

| Preoperative WBC (109/L), median (IQR) | 10.2 (5.8) | 10.4 (6.1) | 9.0 (4.3) | 0.209 |

| Preoperative albumin ≤ 34 g/L, n (%) | 158 (55.4) | 142 (60.7) | 16 (31.4) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative CRP > 22 mg/L, n (%) | 87 (30.5) | 87 (30.5) | 4 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin (>15.3 g/dL), n (%) | 61 (21.4) | 56 (23.9) | 5 (9.8) | 0.026 |

| Preoperative creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.48) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.949 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Vomiting, n (%) | ||||

| 1× | 65 (22.8) | 49 (20.9) | 16 (31.4) | 0.108 |

| >1× | 161 (56.5) | 138 (59.0) | 23 (45.1) | 0.070 |

| Days of constipation, n (IQR) | 1 (2) | 0.99 (2.0) | 0.84 (1.0) | 0.060 |

| Bloated abdomen, n (%) | 223 (78.2) | 186 (79.5) | 37 (72.5) | 0.277 |

| Muscular defense, n (%) | 54 (18.9) | 52 (22.2) | 2 (3.9) | 0.003 |

| Imaging techniques | ||||

| Suspicious ultrasound, n (%) *,** | 175 (90.7) | 135 (91.8) | 40 (87.0) | 0.321 |

| Free fluid in imaging, n (%) * | 187 (65.6) | 170 (72.6) | 17 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| Air–fluid level X-ray, n (%) * | 178 (76.1) | 148 (79.1) | 30 (63.8) | 0.028 |

| Transition point in CT-scan, n (%) * | 238 (92.6) | 217 (96.0) | 21 (67.7) | <0.001 |

| Operated Patients (n = 234) | 0 or 1 Previous Surgery (n = 123) | >1 Previous Surgery (n = 111) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical approach, n (%) | ||||

| open | 222 (94.9) | 112 (91.1) | 110 (99.1) | 0.005 |

| started laparoscopically | 23 (9.8) | 20 (16.3) | 3 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| conversion to open procedure (n, % of laparoscopic surgery) * | 11 (47.8) | 9 (45.0) | 2 (66.7) | 0.484 |

| Operative time (min), median (IQR) | 110 (80) | 90 (60) | 130 (100) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty of adhesiolysis, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Easy (<60 min) | 53 (22.6) | 41 (33.3) | 12 (10.8) | |

| More difficult (60–120 min) | 90 (38.5) | 49 (39.8) | 41 (36.9) | |

| Most difficult (>120 min) | 80 (34.2) | 23 (18.7) | 57 (51.4) | |

| Cause of ileus, n (%) | ||||

| Single adhesion | 75 (32.1) | 57 (46.3) | 18 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| Multiple adhesions | 141 (60.3) | 50 (40.7) | 91 (82.0) | <0.001 |

| Serosal injury, n (%) | 86 (36.8) | 33 (26.8) | 53 (47.7) | <0.001 |

| Enterotomy, n (%) | 33 (14.1) | 14 (11.4) | 19 (17.1) | 0.208 |

| Small bowel segmental resection, n (%) | 47 (20.1) | 23 (18.7) | 24 (21.6) | 0.577 |

| Anastomosis, n (%) | 47 (20.1) | 23 (18.7) | 24 (21.6) | 0.577 |

| Stoma, n (%) | 14 (6.0) | 7 (5.7) | 7 (6.3) | 0.843 |

| Operative Group vs. Conservative Treatment Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| OR | 95% CI | p | ||

| Age (>68 vs. ≤68 years) | 0.075 | - | - | - |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.362 | - | - | - |

| ASA (I/II vs. III/IV) | 0.456 | - | - | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (>25 vs. ≤25) | 0.703 | - | - | - |

| Arterial hypertension (no vs. yes) | 0.292 | - | - | - |

| Coronary heart disease (no vs. yes) | 0.892 | - | - | - |

| Diabetes (no vs. yes) | 0.966 | - | - | - |

| 0 or 1 previous surgery | <0.001 | 4.7 | 1.4–15.1 | 0.009 |

| Preoperative albumin ≤ 34 g/L | <0.001 | 4.5 | 1.4–14.3 | 0.011 |

| Preoperative CRP > 22 mg/L | <0.001 | 8.2 | 0.9–71.6 | 0.058 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin (>15.3 g/dL) | 0.026 | 5.0 | 0.8–29.0 | 0.071 |

| Muscular defense | 0.003 | 4.6 | 0.4–46.5 | 0.197 |

| Suspicious ultrasound | 0.323 | - | - | - |

| Free fluid in diagnostic imaging | <0.001 | 3.6 | 1.3–10.3 | 0.015 |

| Air–fluid levels in X-ray | 0.028 | 3.5 | 1.2–10.6 | 0.024 |

| Transition point in CT scan | <0.001 | 11.4 | 2.4–54.5 | 0.002 |

| Risk Group | Score Range | Number of Patients, n | Surgery, n | Risk of Surgery, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | 0–2 points | 42 | 9 | 21.4 |

| Intermediate risk | 3–4 points | 132 | 117 | 88.6 |

| High risk | 5–6 points | 111 | 108 | 97.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Buniatov, T.; Maak, M.; Jacobsen, A.; Czubayko, F.; Denz, A.; Krautz, C.; Weber, G.F.; Grützmann, R.; Brunner, M.; Mittelstädt, A. Prediction and Risk Evaluation for Surgical Intervention in Small Bowel Obstruction †. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010297

Buniatov T, Maak M, Jacobsen A, Czubayko F, Denz A, Krautz C, Weber GF, Grützmann R, Brunner M, Mittelstädt A. Prediction and Risk Evaluation for Surgical Intervention in Small Bowel Obstruction †. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010297

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuniatov, Timur, Matthias Maak, Anne Jacobsen, Franziska Czubayko, Axel Denz, Christian Krautz, Georg F. Weber, Robert Grützmann, Maximilian Brunner, and Anke Mittelstädt. 2026. "Prediction and Risk Evaluation for Surgical Intervention in Small Bowel Obstruction †" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010297

APA StyleBuniatov, T., Maak, M., Jacobsen, A., Czubayko, F., Denz, A., Krautz, C., Weber, G. F., Grützmann, R., Brunner, M., & Mittelstädt, A. (2026). Prediction and Risk Evaluation for Surgical Intervention in Small Bowel Obstruction †. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010297