Idiopathic True Aneurysms of the Brachial Artery: A Short Case Series and Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

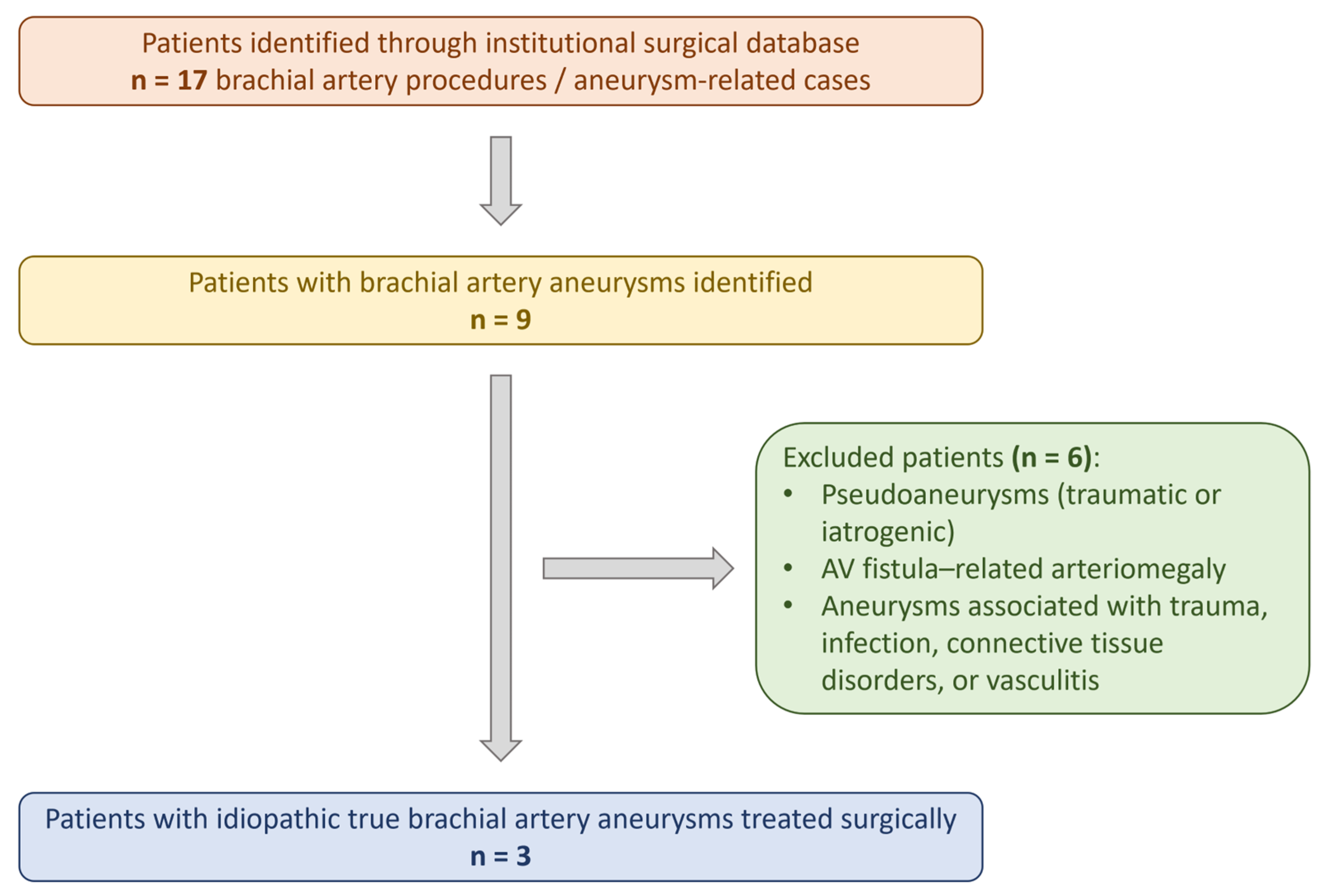

2.1. Study Design

- a retrospective single-center case series of patients treated for idiopathic true brachial artery aneurysms, and

- a scoping review of the literature, conducted in accordance with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines.

2.2. Institutional Case Series

2.3. Literature Search Strategy

- “brachial artery aneurysm”;

- “true brachial artery aneurysm”;

- “idiopathic brachial artery aneurysm”;

- “upper extremity aneurysm”;

- “peripheral arterial aneurysm”.

2.4. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

- Reported true aneurysms of the brachial artery;

- Were classified as idiopathic, with no identifiable secondary cause;

- Provided clinical, imaging, and/or operative data.

- Pseudoaneurysms;

- Aneurysms related to trauma, infection, connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, congenital syndromes, or arteriovenous fistulas;

- Non-brachial upper extremity aneurysms;

- Non-English publications or studies without accessible full text.

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Case Series

3.1. Case 1

3.2. Case 2

3.3. Case 3

4. Discussion and Literature Review

5. Results

5.1. Incidence

5.2. Pathophysiology

5.3. Clinical Symptoms

5.4. Diagnosis

5.5. Treatment

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, A.A.; Hussein, A.M.; Abdi, H.K.; Siyad, A.A.A.; Keilie, A.M.W.; Ahmed, F.M. Spontaneous true brachial artery aneurysm: A case report from Somalia. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2025, 127, 110866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shaban, Y.; Elkbuli, A.; Geraghty, F.; Boneva, D.; McKenney, M.; De La Portilla, J. True brachial artery aneurysm: A case report and review of literature. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 56, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Igari, K.; Kudo, T.; Toyofuku, T.; Jibiki, M.; Inoue, Y. Surgical treatment of aneurysms in the upper limbs. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 2013, 6, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, A.; Sen, I.; De Martino, R.; Erben, Y.; Davila, V.; Ciresi, D.; Beckermann, J.; Carmody, T.; Tallarita, T. Presentation, treatment, and outcomes of brachial artery aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 81, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X. True Brachial Artery Aneurysm in an Adolescent. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2025, 69, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guntani, A.; Takeshita, M.; Yasunaga, C.; Nakayama, K.; Mii, S.; Komori, K. Inflammatory brachial artery aneurysm with amyloidosis due to nontuberculous mycobacterial infection: A case report. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2025, 11, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ouhmich, M.; Banana, Y.; Anane, O.; Rezziki, A.; Benzirar, A.; El Mahi, O. Brachial Artery Aneurysm After Fistula Ligation in a Hemodialysis Patient: A Case Report. Cureus 2025, 17, e88852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Murugesan, P.; Yesuvadiyan, J.P.; Selvaraj, K.; Pattabi, S. A Time Bomb in the Arm: Rare Delayed Presentation of a Post-traumatic True Brachial Artery Aneurysm. Cureus 2025, 17, e86102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hammad Alam, S.M.; Moin, S.; Gilani, R.; Jawad, N.; Abbas, K.; Ellahi, A. True brachial artery aneurysm: A systematic review. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2024, 74, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagaratnam, S.; Choong, A.; Lau, T.; Munro, M.; Loh, A. Swelling in the upper arm: The presentation and management of an isolated brachial artery aneurysm. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2011, 93, e37–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taghi, H.; Zahdi, O.; Hormat-Allah, M.; Bakkali, T.; El Bhali, H.; Sefiani, Y.; El Mesnaoui, A.; Lekehal, B. Idiopathic true isolated aneurysm of the brachial artery. J. Med. Vasc. 2020, 45, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudorović, N.; Lovričević, I.; Franjić, D.B.; Brkić, P.; Tomas, D. True aneurysm of brachial artery. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr 2010, 122, 588–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, P.; Mahapatra, S.; Rajesh, R. True Aneurysm of the Proximal Brachial Artery. Aorta 2013, 1, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bahcivan, M.; Yuksel, A. Idiopathic true brachial artery aneurysm in a nine-month infant. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 8, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaikaus, J.; Moseley, M.D.; Dwivedi, A.J.; Sigdel, A. A Large True Brachial Artery Aneurysm in an Infant. Am. Surg. 2022, 88, 1938–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirji, S.A.; Knell, J.K.; Kim, H.B.; Fishman, S.J.; Taghinia, A. Spontaneous isolated true aneurysms of the brachial artery in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2017, 18, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senarslan, D.A.; Yildirim, F.; Tetik, O. Three Cases of Large-Diameter True Brachial and Axillary Artery Aneurysm and a Review of the Literature. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 57, 273.e11–273.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, E.T.; Mass, D.P.; Bassiouny, H.S.; Zarins, C.K.; Gewertz, B.L. True aneurysmal disease in the hand and upper extremity. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1991, 5, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanhainen, A.; Van Herzeele, I.; Bastos Goncalves, F.; Bellmunt Montoya, S.; Berard, X.; Boyle, J.R.; D’Oria, M.; Prendes, C.F.; Karkos, C.D.; Kazimierczak, A.; et al. Editor’s Choice—European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2024 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-Iliac Artery Aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2024, 67, 192–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhanu, D.L.; Mendere, D.B.; Chala, Z.G.; Bekele, F.A. True brachial artery aneurysm in a 3-year-old: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2025, 132, 111456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sowdagar, S.; Jha, A.; Vasanth, P.; Mathew, J. A Clinical Case Report of Deficiency of Adenosine Deaminase 2 Syndrome (DADA 2) Presenting as a Brachial Artery Aneurysm. Mediterr. J. Rheumatol. 2025, 36, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Treatment of idiopathic true giant brachial aneurysm using artificial vascular graft: A case report. Asian J. Surg. 2024, 47, 3907–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chimada, B.Y.; Hachiro, K.; Takashima, N.; Suzuki, T. Successful revascularization using a saphenous vein for a ruptured brachial artery aneurysm in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2023, 10, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nurmeev, I.; Osipov, D.; Okoye, B. Aneurysm of Upper Limb Arteries in Children: Report of Five Cases. Case Rep. Med. 2020, 2020, 9198723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sarkar, R.; Coran, A.G.; Cilley, R.E.; Lindenauer, S.M.; Stanley, J.C. Arterial aneurysms in children: Clinicopathologic classification. J. Vasc. Surg. 1991, 13, 47–56; discussion 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.M.; Eliason, J.L.; Ganesh, S.K.; Blatt, N.B.; Stanley, J.C.; Coleman, D.M. Pediatric nonaortic arterial aneurysms. J. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 63, 466–476.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.; Han, I.Y.; Cho, K.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Park, K.T.; Kang, M.S. Recurrent true brachial artery aneurysm. Korean J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 44, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Godwin, S.C.; Shawker, T.; Chang, B.; Kaler, S.G. Brachial artery aneurysms in Menkes disease. J. Pediatr. 2006, 149, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangopadhyay, N.; Chong, T.; Chhabra, A.; Sammer, D.M. Brachial Artery Aneurysm in a 7-Month-Old Infant: Case Report and Literature Review. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2016, 4, e625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dayanır, O.B.; Silistreli, E.E. [MEP-02] A Buerger’s Patient with Brachial Artery Aneurysm. Turk. Gogus. Kalp. Damar. Cerrahisi. Derg. 2024, 32, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tadayon, N.; Zarrintan, S.; Kalantar-Motamedi, S.M.R. Acute right upper extremity ischemia resulting from true aneurysm of right brachial artery: A case report. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 2020, 12, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pradhananga, A.; Chao, X. True Brachial Artery Aneurysm Presenting as a Non-Pulsatile Mass. JNMA J. Nepal. Med. Assoc. 2017, 56, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhree, M.B.A.; Azhough, R.; Hafez Quran, F. A case of true brachial artery aneurysm in an elderly male. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 2012, 4, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jardine-Brown, C.P. Right brachial artery arteriosclerotic aneurysm with distal thromboembolic phenomena. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1972, 65, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heydari, F.; Taheri, M.; Esmailian, M. Brachial Artery Aneurysm as a Limb Threatening Condition: A Case Report. Emergency 2015, 3, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fann, J.I.; Wyatt, J.; Frazier, R.L.; Cahill, J.L. Symptomatic brachial artery aneurysm in a child. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1994, 29, 1521–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasavada, A.; Agrawal, N.; Parekh, P.; Vinchurkar, M. Incidentally detected large idiopathic brachial artery aneurysm: A potentially life-threatening discovery. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, bcr2014204745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gonzalez-Urquijo, M.; Marine, L.; Vargas, J.F.; Valdes, F.; Mertens, R.; Bergoeing, M.; Torrealba, J. True Idiopathic Brachial Artery Aneurysm Treated with a Saphenous Vein Graft. Vasc. Endovascular. Surg. 2022, 56, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Mrad, M.; Neifer, C.; Ghedira, F.; Ghorbel, N.; Denguir, R.; Khayati, A. A True Distal Brachial Artery Aneurysm Treated with a Bifurcated Saphenous Vein Graft. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 31, 207.e9–207.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, R.J.; Stone, W.M.; Fowl, R.J.; Cherry, K.J.; Bower, T.C. Management of true aneurysms distal to the axillary artery. J. Vasc. Surg. 1998, 28, 606–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edavalapati, S.; Hamilton, C.; Curtiss, S. Idiopathic brachial true aneurysm in 28-year-old female. Ann. Vasc. Surg.—Brief Rep. Innov. 2025, 5, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovic, L.B.; Kostic, D.M.; Jakovljevic, N.S.; Kuzmanovic, I.L.; Simic, T.M. Vascular thoracic outlet syndrome. World J. Surg. 2003, 27, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konishi, T.; Ohki, S.; Saito, T.; Misawa, Y. Crutch-induced bilateral brachial artery aneurysms. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 9, 1038–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemla, E.; Nortley, M.; Morsy, M. Brachial artery aneurysms associated with arteriovenous access for hemodialysis. Semin. Dial. 2010, 23, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fendri, J.; Palcau, L.; Cameliere, L.; Coffin, O.; Felisaz, A.; Gouicem, D.; Dufranc, J.; Laneelle, D.; Berger, L. True Brachial Artery Aneurysm after Arteriovenous Fistula for Hemodialysis: Five Cases and Literature Review. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 39, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghazanfar, A.; Asghar, A.; Khan, N.U.; Abdullah, S. True brachial artery aneurysm in a child aged 2 years. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2016216429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yuan, Y.; Lu, H.J. True Brachial Artery Aneurysm. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2016, 52, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.Y.V.; Natalwala, I.; Tahir, N.; Bains, R.D. A Rare Case of Brachial Artery Aneurysm in a 9-Month-Old Infant. Vasc. Endovascular. Surg. 2024, 58, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetik, O.; Ozcem, B.; Calli, A.O.; Gurbuz, A. True brachial artery aneurysm. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2010, 37, 618–619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bautista-Sánchez, J.; Cuipal-Alcalde, J.D.; Bellido-Yarlequé, D.; Rosadio-Portilla, L.; Gil-Cusirramos, M. True Brachial Aneurysm in an Older Female Patient. A Case Report and Review of Literature. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2022, 78, 378.e1–378.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, N.; Kisku, N.; Gupta, L.; Geelani, M.A. True Idiopathic Brachial Artery Aneurysm: A Rare Case of Surgical Emergency. Indian J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017, 4, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, M.A.; Khan, A.M.; Akram, Y. Brachial Artery Aneurysm. Japan Med. Assoc. J. 2006, 49, 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Parvin, S.D.; Bailey, I.S. Brachial artery aneurysm in a five-year-old girl. Eur. J. Vasc. Surg 1987, 1, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.I.; Salamone, L.; Chang, J.; Harris, E.J. Idiopathic true brachial artery aneurysm in an 18-month-old girl. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 56, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, F.; Asciutto, G.; Usai, M.V. Axillary artery aneurysms in pediatric patients: A narrative review. Vascular 2024, 32, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taketani, S.; Imagawa, H.; Kadoba, K.; Sawa, Y.; Sirakura, R.; Matsuda, H. Idiopathic iliac arterial aneurysms in a child. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1997, 32, 1519–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagès, O.N.; Alicchio, F.; Keren, B.; Diallo, S.; Lefebvre, F.; Valla, J.S.; Poli-Merol, M.L. Management of brachial artery aneurysms in infants. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2008, 24, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowafy, K.A.; Soliman, M.A. A Large Isolated True Brachial Artery Aneurysm in 6 months boy: Managed Surgically with Perfect Outcome. A Case Report. Int. J. Angiol. Vasc. Surg. 2020, 3, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.R.; Frusha, J.D.; Stromeyer, F.W. Brachial artery aneurysm in an infant: Case report and review of the literature. J. Vasc. Surg. 1988, 7, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, J.; Fitridge, R. Update on aneurysm disease: Current insights and controversies: Peripheral aneurysms: When to intervene—Is rupture really a danger? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 56, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schunn, C.D.; Sullivan, T.M. Brachial arteriomegaly and true aneurysmal degeneration: Case report and literature review. Vasc. Med. 2002, 7, 25–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Wu, X.; Cao, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, K.; Liu, B. Endovascular management of spontaneous axillary artery aneurysm: A case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2013, 28, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Criado, E.; Marston, W.A.; Ligush, J.; Mauro, M.A.; Keagy, B.A. Endovascular repair of peripheral aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms, and arteriovenous fistulas. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 1997, 11, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadoulas, S.; Stathopoulou, M.; Tsimpoukis, A.; Papageorgopoulou, C.; Nikolakopoulos, K.; Krinos, N.; Skandali, A.; Zampakis, P.; Mustaqe, P.; Dogjani, A.; et al. Simultaneous Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair and Open Repair of Common Femoral Artery Aneurysm: Short Case Series and Current Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetik, O.; Yilik, L.; Besir, Y.; Can, A.; Ozbek, C.; Akcay, A.; Gurbuz, A. Surgical treatment of axillary artery aneurysm. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2005, 32, 186–188; discussion 185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maskanakis, A.; Patelis, N.; Moris, D.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Schizas, D.; Diakomi, M.; Bakoyiannis, C.; Georgopoulos, S.; Klonaris, C.; Liakakos, T. Stenting of Subclavian Artery True and False Aneurysms: A Systematic Review. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 47, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaluk, B.T.; Deutsch, E.; Moufid, R.; Panetta, T.F. Endovascular repair of an axillary artery pseudoaneurysm attributed to hyperextension injury. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 23, 412.e5–412.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, F.; Güvendi Şengör, B.; İzci, S. Successful management of a brachial artery aneurysm with percutaneous intervention and one-month rivaroxaban therapy. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2021, 25, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, G.; Ozen, S.; Ozen, A.; İşcan, H.Z. Isolated brachial artery aneurysm successfully treated with a covered stent in a patient with Behcet’s disease. Turk. Gogus. Kalp. Damar. Cerrahisi. Derg. 2019, 27, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beregi, J.P.; Prat, A.; Willoteaux, S.; Vasseur, M.A.; Boularand, V.; Desmoucelle, F. Covered stents in the treatment of peripheral arterial aneurysms: Procedural results and midterm follow-up. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 1999, 22, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, H.F.; Bledsoe, J.H.; Char, F.; Williams, G.D. Abdominal aortic aneurysmectomy in a 17-year-old patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: Case report and review of the literature. Surgery 1973, 74, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Patient ID/Year | Age/Sex | Symptoms/ Signs | Side/ Location | Size (cm) | Repair | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/ 2001 | 28/M | No/ Palpable mass | R/Distal third of BA, extending to ulnar artery | 3.5 | Aneurysm excision & reversed BV interposition between BA & RA, UA ligation | NA |

| 2/ 2007 | 46/M | No/ Palpable mass | L/ Distal half of BA | 4 | Aneurysm excision & reversed BV interposition | NA |

| 3/ 2015 | 65/M | No/ Palpable mass | L/ Two proximal thirds of BA | 4 | Aneurysm excision & reversed BV interposition | NA |

| ID | Author/Ref | Journal/ Year | Age/ Sex | Symptoms/Side | Signs/ Size (cm) | Time | DI | Treatment/ Fu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Berhanu DL et al. [20] | Int J Surg Case Rep/2025 | 3 y/ F | No/ L | Painless swelling/1.7 × 1.6 | 2 w | CDU, CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 2 | Ali AA et al. [1] | Int J Surg Case Rep/2025 | 28 y/ F | Yes/ L | Painful swelling/NR | 2 y | CDU | AE & Interposition grafting with PTFE graft 8 mm/ 6 m |

| 3 | Zhang L et al. [5] | Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg/ 2025 | 14 y/ M | No/ L | Pulsatile mass/ 3 × 3 | NR | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with BV graft/ 6 y |

| 4 | Liao Z et al. [22] | Asian J Surg/ 2024 | 78 y/ F | No/ L | Pulsating mass/ 3.4 × 2.2 × 3.5 | 2 y | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with PTFE graft/ 5 y |

| 5 | Lee CYV et al. [48] | Vasc Endovasc Surg/ 2024 | 9 m/ NR | No/ L | Swelling/ 2 × 2 | 2 m | CDU, MRA | AE & Interposition grafting with CV vein graft/ NR |

| 6 | Gonzalez-Urquijo M et al. [38] | Vasc Endovascular Surg/2022 | 65 y/ F | Yes/ L | Pain, pulsatile mass/ 2 × 6 | NR | CDU, MRA | Bypass with GSV graft & sac embolization with Gelita-spon/ NR |

| 7 | Bautista-Sánchez J et al. [50] | Ann Vasc Surg/ 2022 | 67 y/ F | No/ L | pulsatile mass/ NR | NR | NR | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 8 | Tadayon N et al. [31] | J Cardio-vasc Thorac Res/2020 | 66 y/ F | Yes/ R | Aneurysm thrombosis & distal embolism, AI/ 2 × 2.5 × 3 | 12 h | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft, ligation of RA/ 6 m |

| 9 | Shaban Y et al. [2] | Ann Med Surg (Lond)/2020 | 83 y/ M | Yes/ R | Pain, swelling, pulsatile mass, AI/ 0.9 | 1 w | CDU, CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV (2 grafts)/ 6 m |

| 10 | Nurmeev I et al. [24] | Case Rep Med/ 2020 | NR | NR | NR | NR | CDU | AE & Interposition grafting/ 1–3 y |

| 11 | Taghi H et al. [11] | J Med Vasc/ 2020 | 70 y/ F | Yes/ R | Paresthesia, swelling, nerve compression/ 2.6 × 3.5 | 3 y | CDU, CTA | AE & End-to-end anastomosis/ NR |

| 12 | Senarslan DA et al. [17] | Ann Vasc Surg/ 2019 | 27 y/ M | Yes/ L | Pain, numbness, embolism, AI/ 3 aneurysms: 3 × 2.8, 4.7 × 4.4, 2.4 × 2.1 | NR | CTA | Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 13 | 81 y/ F | Yes/ L | Digital gangrene/ 5 × 10 | NR | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft (proximal anastomosis end-to-side due to increased axillary diameter)/ 12 m | ||

| 14 | 78 y/ M | Yes/ L | Pain, cyanosis, numbness/ 3 × 10 | NR | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with biological graft Omniflow/ 6 m | ||

| 15 | Pradhananga A et al. [32] | J Nepal Med Assoc/2017 | 59 y/ M | Yes/ L | Pain, AI/ NR | 8 h | CDU | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 16 | Ghazanfar A et al. [46] | BMJ Case Rep/ 2016 | 2 y/ M | No/ R | Swelling/ 4 × 3 | NR | CDU, CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 17 | Yuan Y et al. [47] | Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg/ 2016 | 38 y/ M | Yes/ R | Painful pulsatile mass/ 3.5 × 4 | NR | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 18 | Ben Mrad M et al. [39] | Ann Vasc Surg/ 2016 | 40 y/ M | Yes/ L | Painfull pulsatile mass/3.7 × 4.2 × 6 cm | NR | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV bifurcated graft/ 1 y |

| 19 | Greenberg JI et al. [54] | J Vasc Surg/ 2012 | 18 m/F | Yes/ L | Arm swelling/ 1.2 | NR | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 20 | A Fakhree MB et al. [33] | J Cardiovasc Thorac Res/2012 | 67 y/ M | Yes/ R | Aneurysm thrombosis, AI/ 2 | 1 w | CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ 1 m |

| 21 | Alagaratnam S et al. [10] | Ann R Coll Surg Engl/2011 | 64 y/ F | Yes/ L | Swelling, paresthesia nerve compression/ 3 × 5 cm | 2 m | CDU, CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 22 | Tetik O et al. [49] | Tex Heart Inst J/ 2010 | 50 y/ F | Yes/ R | Swollen pulsatile mass/ 4 × 2.5 | NR | DSA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 23 | Hudorović N et al. [12] | Wien Klin Wochenschr/ 2010 | 77 y/ F | No/ L | Swelling/ 5 × 4 | 2 y | CDU, CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 24 | Bahcivan M et al. [14] | Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg/ 2009 | 9 m/ M | No/ L | Pulsatile mass/ 3.5 × 3.2 | 1 m | CDU, MRA | AE & End to end anastomosis/ NR |

| 25 | Pagès ON et al. [57] | Pediatr Surg Int/2008 | 3 m/ M | NR | NR/ 0.6 | NR | CDU/MRA | AE & End to end anastomosis/ NR |

| 26 | 1 y/M | NR | NR /3 | NR | CDU/MRA | AE & Interposition grafting with BV graft/ NR | ||

| 27 | 13 m/M | NR | NR | NR | CDU/MRA | AE & Interposition grafting with BV graft/ NR | ||

| 28 | Gray RJ et al. [40] | J Vasc Surg/ 1998 | NR | NR | Aneurysm thrombosis/ 5.3 | NR | NR | AE & revascularization with GSV graft/ NR |

| 29 | NR | NR | Symptomatic mass/ 3.8 | 10 y | NR | AE & revascularization with internal iliac artery graft/ NR | ||

| 30 | Gangopadhyay N et al. [29] | Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open/2016 | 7 m/ M | Yes/ L | Impaired MN function/ 2 × 2.4 | 10 d | CDU, MRA | NR/ 1 m |

| 31 | Jones TR et al. [59] | J Vasc Surg/ 1988 | 9 m/ M | No/ L | Pulsatile mass/ 0.6 × 1 | NR | CDU | AE & End-to-end anastomosis/ NR |

| 32 | Jardine-Brown CP et al. [34] | Proc R Soc Med/ 1972 | 78 y/ M | Yes/ R | AI, pain, cyanosis/ 7 × 5 | 10 d | NR | AL & GSV bypass & homolateral cervical sympathectomy/ NR |

| 33 | Fann JI et al. [36] | J Pediatr Surg/ 1994 | 3 y/ M | Yes/L No/R | L: AI/ 1.8 × 3.5 R: Pulsatile mass/ 1.1 × 2.6 | NR | CDU | L&R: AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR |

| 34 | Hirji SA et al. [16] | Journal of Pediatr Surg Case Rep/ 2017 | 9 m/ F | No/ L | Pulsatile mass/ 1.7 × 1 | 2 w | CDU | AE & Interposition grafting with BV graft/ NR |

| 35 | 3 y/ F | No/ R | Pulsatile mass/ 3 × 0.9 | Few w | CDU, MRA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft/ NR | ||

| 36 | Mowafy KA et al. [58] | Int J Angiol Vasc Surg/2020 | 6 m/ M | Yes/ R | Tender swelling, impaired, painful mobility/ 5.5 × 1.8 | 1 m | CDU | AE & Interposition grafting with BV graft/ NR |

| 37 | Vasavada A et al. [37] | BMJ Case Rep/ 2015 | 58 y/ M | No/ R | Incidental finding during CA/ NR | NR | CA | Conservative management/ 3 m |

| 38 | Heydari F et al. [35] | Emerg (Tehran)/2015 | 52 y/ M | Yes/ R | AI/2.5 × 2.2 | NR | CDU, CTA | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft, embolectomy |

| 39 | Raja N et al. [51] | Indian J of Vasc and Endo-vasc Surg/ 2017 | 53 y/ M | Yes/ R | Pulsatile mass/ 4 | NR | CDU | AE & Interposition grafting with GSV graft, embolectomy/ NR |

| 40 | Edavalapati S et al. [41] | Am Surg/2022 | 28 y/ F | No/ L | Pulsatile mass/ 2 | NR | CDU, MRI | AE & End-to-end anastomosis/6 m |

| 41 | Kaikaus J et al. [15] | Annals of Vasc Surg—Brief Rep and Innov/ 2025 | 6 m/ M | No/ L | Pulsatile mass/ 2 | NR | CTA | AE & Lateral aneurysmorraphy/ NR |

| 42 | Ghazi MA et al. [52] | Japan Med Assoc J/ 2006 | 27 y/ F | No/ R | Painless swelling/ 3.2 ×2 | 6 y | CDU | AE & End-to-end anastomosis/ 2 m |

| 43 | Parvin SD et al. [53] | Eur J Vasc Surg/ 1987 | 5 y/ F | Yes/ R | Pulsatile swelling/3 × 2 | 8 w | NR | AL/ 6 m |

| Domain | Key Observations from the Literature |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Predominantly adults; both sexes affected; idiopathic etiology without trauma, infection, or connective tissue disease |

| Clinical presentation | Most commonly a palpable upper-arm mass; may be associated with pain, tenderness, or local compression symptoms; ischemic manifestations reported less frequently; some cases detected incidentally |

| Aneurysm morphology and location | Typically, fusiform true aneurysms; most often involving the mid-to-distal brachial artery, occasionally extending to the bifurcation |

| Diagnostic modalities | Duplex ultrasonography as first-line imaging; computed tomography angiography frequently used for anatomical delineation and operative planning |

| Treatment strategy | Predominantly open surgical repair; conservative management reported rarely and mainly in asymptomatic or high-risk patients |

| Surgical techniques | Aneurysm excision with arterial reconstruction most commonly performed; end-to-end anastomosis feasible in selected cases |

| Conduit choice | Not reported for idiopathic true brachial artery aneurysms; endovascular approaches described mainly for non-idiopathic aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms |

| Reported outcomes | Early postoperative outcomes generally favorable; mid- and long-term outcomes derived from literature reports rather than institutional follow-up |

| Follow-up considerations | Long-term surveillance recommended due to potential development of aneurysms at other arterial sites |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leonida, M.; Papadoulas, S.; Stathopoulou, M.S.; Tsimpoukis, A.; Papageorgopoulou, C.; Nikolakopoulos, K.; Krinos, N.; Skandali, A.; Theofanis, G.; Antzoulas, A.; et al. Idiopathic True Aneurysms of the Brachial Artery: A Short Case Series and Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010295

Leonida M, Papadoulas S, Stathopoulou MS, Tsimpoukis A, Papageorgopoulou C, Nikolakopoulos K, Krinos N, Skandali A, Theofanis G, Antzoulas A, et al. Idiopathic True Aneurysms of the Brachial Artery: A Short Case Series and Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010295

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonida, Maria, Spyros Papadoulas, Melina S. Stathopoulou, Andreas Tsimpoukis, Chrysanthi Papageorgopoulou, Konstantinos Nikolakopoulos, Nikolaos Krinos, Aliki Skandali, George Theofanis, Andreas Antzoulas, and et al. 2026. "Idiopathic True Aneurysms of the Brachial Artery: A Short Case Series and Scoping Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010295

APA StyleLeonida, M., Papadoulas, S., Stathopoulou, M. S., Tsimpoukis, A., Papageorgopoulou, C., Nikolakopoulos, K., Krinos, N., Skandali, A., Theofanis, G., Antzoulas, A., Litsas, D., Papadopoulos, P. D., Zampakis, P., Maroulis, I., Leivaditis, V., & Mulita, F. (2026). Idiopathic True Aneurysms of the Brachial Artery: A Short Case Series and Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 295. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010295