Coronary Sinus Reduction for Refractory Angina Caused by Microvascular Dysfunction—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Background

2. Current Clinical Solutions for Patients with CMD

3. Coronary Sinus Occlusion—Physiological Perspective

4. Coronary Sinus Occlusion—Molecular Perspective

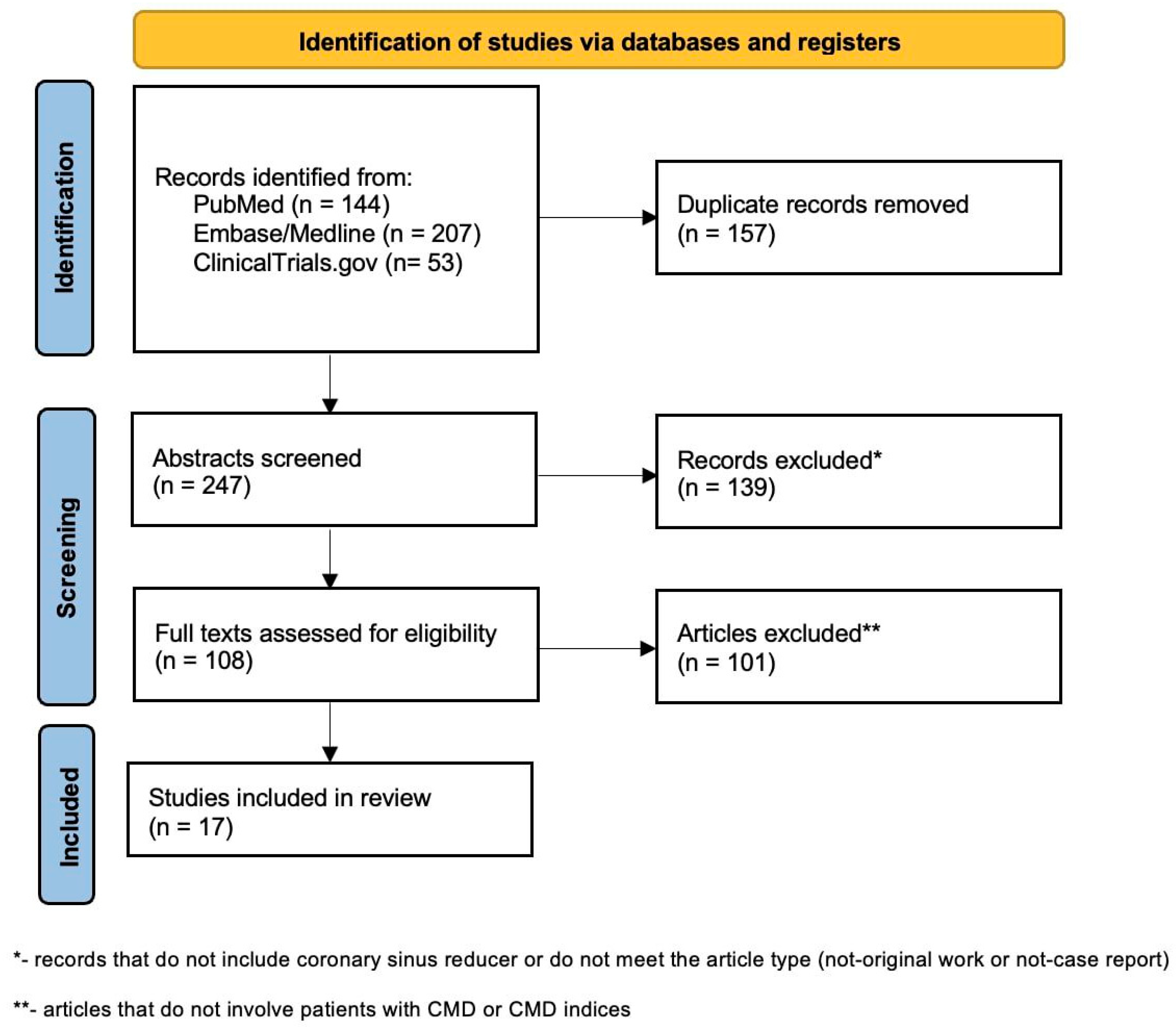

5. Current Evidence and Ongoing Trials in CMD Population—Systematic Review

CMD—Coronary Microvascular Disease

6. Limitations and Challenges

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kunadian, V.; Chieffo, A.; Camici, P.G.; Berry, C.; Escaned, J.; Maas, A.; Prescott, E.; Karam, N.; Appelman, Y.; Fraccaro, C.; et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology & Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 3504–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerhout, C.K.M.; de Waard, G.A.; Lee, J.M.; Mejia-Renteria, H.; Lee, S.H.; Jung, J.H.; Hoshino, M.; Echavarria-Pinto, M.; Meuwissen, M.; Matsuo, H.; et al. Prognostic value of structural and functional coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients with non-obstructive coronary artery disease; from the multicentre international ILIAS registry. EuroIntervention 2022, 18, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camici, P.G.; Crea, F. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Buono, M.G.; Montone, R.A.; Camilli, M.; Carbone, S.; Narula, J.; Lavie, C.J.; Niccoli, G.; Crea, F. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Across the Spectrum of Cardiovascular Diseases: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1352–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M.J.; Rajkumar, C.A.; Ahmed-Jushuf, F.; Simader, F.A.; Chotai, S.; Pathimagaraj, R.H.; Mohsin, M.; Salih, A.; Wang, D.; Dixit, P.; et al. Coronary sinus reducer for the treatment of refractory angina (ORBITA-COSMIC): A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2024, 403, 1543–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheye, S.; Jolicoeur, E.M.; Behan, M.W.; Pettersson, T.; Sainsbury, P.; Hill, J.; Vrolix, M.; Agostoni, P.; Engstrom, T.; Labinaz, M.; et al. Efficacy of a device to narrow the coronary sinus in refractory angina. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, N.D.; Michelsen, M.M.; Pena, A.; Frestad, D.; Dose, N.; Aziz, A.; Faber, R.; Host, N.; Gustafsson, I.; Hansen, P.R.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Function and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Women with Angina Pectoris and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: The iPOWER Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepine, C.J.; Anderson, R.D.; Sharaf, B.L.; Reis, S.E.; Smith, K.M.; Handberg, E.M.; Johnson, B.D.; Sopko, G.; Bairey Merz, C.N. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 2825–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, W.B.; Barrett, E.J. Microvascular Dysfunction in Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiometabolic Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, U.; Schram, M.T.; Houben, A.J.; Muris, D.M.; Stehouwer, C.D. Microvascular dysfunction as a link between obesity, insulin resistance and hypertension. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 103, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, A.J.; Ford, T.J.; Mangion, K.; Kotecha, T.; Rakhit, R.; Galasko, G.; Hoole, S.; Davenport, A.; Kharbanda, R.; Ferreira, V.M.; et al. Rationale and design of the Medical Research Council’s Precision Medicine with Zibotentan in Microvascular Angina (PRIZE) trial. Am. Heart J. 2020, 229, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wlodarczak, S.; Rola, P.; Jastrzebski, A.; Turkiewicz, K.; Korda, A.; Wlodarczak, P.; Barycki, M.; Kulczycki, J.J.; Furtan, L.; Wlodarczak, A.; et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Coronary Sinus Reducer in the Therapy of Refractory Angina Pectoris-Mid-Term Results of the Real-Life Cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Leor, O.; Jimenez Valero, S.; Gomez-Lara, J.; Escaned, J.; Avanzas, P.; Fernandez, S.; en Representacion de los Investigadores del Registro Re2-Cor. Initial experience with the coronary sinus reducer for the treatment of refractory angina in Spain. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 76, 381–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, G.; Giannini, F.; Massussi, M.; Tebaldi, M.; Cafaro, A.; Ielasi, A.; Sgura, F.; De Marco, F.; Stefanini, G.G.; Ciardetti, M.; et al. Usefulness of Coronary Sinus Reducer Implantation for the Treatment of Chronic Refractory Angina Pectoris. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 139, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wusten, B.; Buss, D.D.; Deist, H.; Schaper, W. Dilatory capacity of the coronary circulation and its correlation to the arterial vasculature in the canine left ventricle. Basic Res. Cardiol. 1977, 72, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yada, T.; Hiramatsu, O.; Kimura, A.; Goto, M.; Ogasawara, Y.; Tsujioka, K.; Yamamori, S.; Ohno, K.; Hosaka, H.; Kajiya, F. In vivo observation of subendocardial microvessels of the beating porcine heart using a needle-probe videomicroscope with a CCD camera. Circ. Res. 1993, 72, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilian, W.M.; Marcus, M.L. Phasic coronary blood flow velocity in intramural and epicardial coronary arteries. Circ. Res. 1982, 50, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiya, F.; Tomonaga, G.; Tsujioka, K.; Ogasawara, Y.; Nishihara, H. Evaluation of local blood flow velocity in proximal and distal coronary arteries by laser Doppler method. J. Biomech. Eng. 1985, 107, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Saito, T.; Mitsugi, M.; Saitoh, S.; Niitsuma, T.; Maehara, K.; Maruyama, Y. Effects of cardiac contraction and coronary sinus pressure elevation on collateral circulation. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 271, H1433–H1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, F.A.; Capone, R.J.; Most, A.S.; Gewirtz, H. Effect of pressure-controlled intermittent coronary sinus occlusion on pacing-induced myocardial ischemia in domestic swine. Circulation 1988, 77, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toggart, E.J.; Nellis, S.H.; Liedtke, A.J. The efficacy of intermittent coronary sinus occlusion in the absence of coronary artery collaterals. Circulation 1987, 76, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassab, G.S.; Navia, J.A.; March, K.; Choy, J.S. Coronary venous retroperfusion: An old concept, a new approach. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 104, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izrailtyan, I.; Frasch, H.F.; Kresh, J.Y. Effects of venous pressure on coronary circulation and intramyocardial fluid mechanics. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267, H1002–H1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ido, A.; Hasebe, N.; Matsuhashi, H.; Kikuchi, K. Coronary sinus occlusion enhances coronary collateral flow and reduces subendocardial ischemia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2001, 280, H1361–H1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, G.L.; Alkhalil, M.; Borlotti, A.; Wolfrum, M.; Gaughran, L.; Dall’Armellina, E.; Langrish, J.P.; Lucking, A.J.; Choudhury, R.P.; Kharbanda, R.K.; et al. Index of microcirculatory resistance-guided therapy with pressure-controlled intermittent coronary sinus occlusion improves coronary microvascular function and reduces infarct size in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: The Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction—Pressure-controlled Intermittent Coronary Sinus Occlusion study (OxAMI-PICSO study). EuroIntervention 2018, 14, e352–e359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarsini, R.; Terentes-Printzios, D.; Shanmuganathan, M.; Kotronias, R.A.; Borlotti, A.; Marin, F.; Langrish, J.; Lucking, A.; Ribichini, F.; Oxford Acute Myocardial Infarction, S.; et al. Pressure-controlled intermittent coronary sinus occlusion improves the vasodilatory microvascular capacity and reduces myocardial injury in patients with STEMI. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 99, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, H.; Olschewski, M.; Munzel, T.; Gori, T. Randomized, crossover, controlled trial on the modulation of cardiac coronary sinus hemodynamics to develop a new treatment for microvascular disease: Protocol of the MACCUS trial. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1133014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, H.; Hammer, P.; Olschewski, M.; Munzel, T.; Escaned, J.; Gori, T. Coronary Venous Pressure and Microvascular Hemodynamics in Patients with Microvascular Angina: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, F.; Palmisano, A.; Baldetti, L.; Benedetti, G.; Ponticelli, F.; Rancoita, P.M.V.; Ruparelia, N.; Gallone, G.; Ancona, M.; Mangieri, A.; et al. Patterns of Regional Myocardial Perfusion Following Coronary Sinus Reducer Implantation: Insights by Stress Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, e009148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmisano, A.; Giannini, F.; Rancoita, P.; Gallone, G.; Benedetti, G.; Baldetti, L.; Tzanis, G.; Vignale, D.; Monti, C.; Ponticelli, F.; et al. Feature tracking and mapping analysis of myocardial response to improved perfusion reserve in patients with refractory angina treated by coronary sinus Reducer implantation: A CMR study. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 37, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrak, M.; Pavšič, N.; Ponticelli, F.; Beneduce, A.; Palmisano, A.; Guarracini, S.; Esposito, A.; Banai, S.; Žižek, D.; Giannini, F.; et al. Efficacy of coronary sinus reducer implantation in patients with chronic total occlusion of the right coronary artery. Kardiol. Pol. 2022, 80, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.; Tan, S.T.; De Silva, R.; Keramida, G. Insights from positron emission tomography into the mechanism of the coronary sinus reducer. Heart 2023, 109, A47–A49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Tan, S.T.; Wechalekar, K.; Keramida, G.; de Silva, R. Redistribution of myocardial perfusion after coronary sinus reducer implantation demonstrated by rubidium-82 positron emission tomography. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2024, 33, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, G.; Polat, V.; Bozcali, E.; Opan, S.; Cetin, N.; Ural, D. Evaluation of serum sST2 and sCD40L values in patients with microvascular angina. Microvasc. Res. 2019, 122, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, J.; Kearney, P.; Clarke, G.; Moloney, G.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. A prospective study of C-reactive protein as a state marker in Cardiac Syndrome X. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 43, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhrs, H.E.; Schroder, J.; Bove, K.B.; Mygind, N.D.; Frestad, D.; Michelsen, M.M.; Lange, T.; Gustafsson, I.; Kastrup, J.; Prescott, E. Inflammation, non-endothelial dependent coronary microvascular function and diastolic function-Are they linked? PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohl, W.; Gangl, C.; Jusic, A.; Aschacher, T.; De Jonge, M.; Rattay, F. PICSO: From myocardial salvage to tissue regeneration. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2015, 16, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.S.; Kim, M. Revascularization of the heart; histologic changes after arterialization of the coronary sinus. Circulation 1952, 5, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apte, R.S.; Chen, D.S.; Ferrara, N. VEGF in Signaling and Disease: Beyond Discovery and Development. Cell 2019, 176, 1248–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbein, L.E.; Foresti, R.; Motterlini, R. Heme Oxygenase-1 and Carbon Monoxide in the Heart: The Balancing Act Between Danger Signaling and Pro-Survival. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1940–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohl, W.; Mina, S.; Milasinovic, D.; Kasahara, H.; Wei, S.; Maurer, G. Is activation of coronary venous cells the key to cardiac regeneration? Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2008, 5, 528–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohl, W.; Spitzer, E.; Mader, R.M.; Wagh, V.; Nguemo, F.; Milasinovic, D.; Jusic, A.; Khazen, C.; Szodorai, E.; Birkenberg, B.; et al. Acute molecular effects of pressure-controlled intermittent coronary sinus occlusion in patients with advanced heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannini, F.; Cuenin, L.; Adjedj, J. Impact of the coronary sinus reducer on the coronary artery circulation cases report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2022, 6, ytac159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebaldi, M.; Campo, G.; Ugo, F.; Guarracini, S.; Marrone, A.; Clò, S.; Abdirashid, M.; Di Mauro, M.; Rametta, F.; Di Marco, M.; et al. Coronary Sinus Narrowing Improves Coronary Microcirculation Function in Patients with Refractory Angina: A Multicenter Prospective INROAD Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, e013481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servoz, C.; Verheye, S.; Giannini, F.; Banai, S.; Fradi, M.; Cuenin, L.; Bellemain-Appaix, A.; Gilard, M.; Benamer, H.; Adjedj, J. Impact of coronary sinus reducer on absolute coronary blood flow and microvascular resistance. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 104, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, F.; Baldetti, L.; Ielasi, A.; Ruparelia, N.; Ponticelli, F.; Latib, A.; Mitomo, S.; Esposito, A.; Palmisano, A.; Chieffo, A.; et al. First Experience with the Coronary Sinus Reducer System for the Management of Refractory Angina in Patients Without Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, 1901–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnan, E.; Cioffi, G.M.; Bossard, M.; Madanchi, M.; Majcen, I.; Zhi, Y.; Gjergjizi, V.; Seiler, T.; Cuculi, F.; Attinger-Toller, A. Treatment of microvascular angina with the coronary sinus reducer: A first experience. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, ehad655.1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konigstein, M.; Banai, S. TCT-673 Coronary Sinus Reducer for the Treatment of Angina with Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (ANOCA). JACC 2024, 84, B258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, J.M.; Brugaletta, S.; Baz Alonso, J.A.; Fam, N.; Abdul-Jawad Altisent, O.; Pasos, J.F.; Portillo, J.D.; Gallo, F.; Rodes-Cabau, J.; Puri, R.; et al. TCT-102 First-in-Man Experience with the Self-Expandable A-Flux Coronary Sinus Reducer for Treating Symptomatic Ischemic Heart Disease. JACC 2024, 84, B265–B266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryon, D.; Corban, M.T.; Alkhouli, M.; Prasad, A.; Raphael, C.E.; Rihal, C.S.; Reeder, G.S.; Lewis, B.; Albers, D.; Gulati, R.; et al. Coronary Sinus Reducer Improves Angina, Quality of Life, and Coronary Flow Reserve in Microvascular Dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoole, S.P.; Tweed, K.; Williams, L.; Weir-McCall, J. Coronary Sinus Reducer Improves Myocardial Perfusion in a Patient with Angina, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, and Coronary Microvascular Disease. CJC Open 2024, 6, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Włodarczak, S.; Rola, P.; Jastrzębski, A.; Barycki, M.; Kędzierska, M.; Korda, A.; Włodarczak, A.; Lesiak, M. Implantation of a coronary sinus reducer for refractory angina due to coronary microvascular dysfunction. Kardiol. Pol. 2024, 82, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.; Keramida, G.; Baksi, A.J.; de Silva, R. Implantation of the coronary sinus reducer for refractory angina due to coronary microvascular dysfunction in the context of apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy—A case report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2022, 6, ytac440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grebmer, C.; Bossard, M.; Attinger-Toller, A.; Kobza, R.; Hilfiker, G.; Berte, B.; Cuculi, F. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with a coronary sinus reducer: A case series. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2023, 7, ytad455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronary Sinus Reducer Implantation in Patients with Ischaemia and Non-Obstructed Coronary Arteries and Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. (REMEDY-PILOT). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05492110?term=remedy-pilot&rank=2 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- A Multicentric Randomized Open Label Controlled Superiority Trial to Evaluate the Effectiveness of a Therapy with a Coronary Sinus Reducer as Compared to Guideline-directed Medical Therapy in Patients with Refractory Microvascular Angina. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04606459?cond=cosima%20&rank=1 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Efficacy of the Coronary Sinus Reducer in Patients with Refractory Angina II. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05102019.

- Myocardial Ischemia by 15O-H2O PET/CT in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease and Refractory Angina—Evaluation of the Coronary Sinus Reduction Stent Method. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06033495 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Impact of Coronary Sinus Flow Reducer on Coronary Microcirculation and Myocardial Ischemia in Patients with Refractory Angina Pectoris. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06266065?term=Impact%20of%20Coronary%20Sinus%20Flow%20Reducer%20on%20Coronary%20Microcirculation%20and%20Myocardial%20Ischemia&rank=1 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Baldetti, L.; Colombo, A.; Banai, S.; Latib, A.; Esposito, A.; Palmisano, A.; Giannini, F. Coronary sinus Reducer non-responders: Insights and perspectives. EuroIntervention 2018, 13, 1667–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DOI/NCT Identificator | First Author or PI | Study Type | Population | Design | Country | Device | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.06.062 | F. Giannini | Observational | 8 patients with

| Observation from baseline to follow-up | Italy | Neovasc |

|

| NCT04606459 | T. Gori | RCT | 144 patients with

| CSR implantation or optimal medical therapy—assessment at 6 months, 1 year and 5 years | Germany | Neovasc |

|

| NCT05102019 | T. D. Henry; G. W. Stone | CMD only in registry arm | 380 patients in total three arms (RCT + registry). In registry arms patients including:

| Registry arm with CSR implantation—maximum follow-up at 5 years | United States and Canada | Neovasc | Primary endpoints:

|

| NCT05492110 | R. E. Silva | RCT—sham-controlled, double-blinded | 54 patients with INOCA:

| CSR implantation or sham-controlled—outcomes at 6 months | England | Neovasc | Primary endpoints:

|

| 10.1093/ehjcr/ytac440 | K. Cheng | Case Report | 38-year-old women with chest pain despite multi anti-anginal drugs, and ischemia probably due to the CMD in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | - | England | - | At 6 months follow-up CCS1 and change in SAQ (+14 points), as well as the reduction of ischemic burden from 16% to <5% |

| 10.1093/ehjcr/ytac159 | F. Giannini | Case Report | Two patients: 58-year-old male after CABG and numerous PCI and 78-year-old man with CTO. Both patients were not suitable for revascularization and on optimal therapy | - | Italy | Neovasc | Increase in CBF—from 100 to 148 mL/min for the first patient and from 107 to 133 mL/min for the second patient and decrease of microvascular resistance from 516 to 362 woods units for the first patient and from 543 to 478 woods units for the second patient. |

| NCT06033495 | Ø. Lie | Observational | 15 patients with:

| CSR implantation and 15O-H2O PET/CT assessment at six months | Norway | Primary outcome:

| |

| 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad655.1296 | E. Gnan | Observational | 8 patients with:

| CSR implantation and observation for a median time of 647.5 (132–732) days | Switzerland | Improvement of CCS (2.9 ± 0.6 to 1.5 ± 0.8) and number of antianginal drugs (2.6 ± 1.6 to 1.9 ± 1.1) | |

| 10.1093/ehjcr/ytad455 | C. Grebmer | Case report | Patient with microvessel disease with therapy refractory angina and non-relevant stenosis of RCA | - | Switzerland | Feasibility of cardiac resynchronization therapy after CSR implantation | |

| NCT06266065 | J. Bulum | Observational | 25 patients with:

| CSR implantation and observation for 2.5 years | Croatia | Primary endpoint:

| |

| 10.1016/j.cjco.2024.07.011 | S. P. Hoole | Case report | 69-year-old woman with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy diagnosed with NSTEMI without obstruction of coronary artery | - | England | Shockwave | Improvement of CCS—3 to 2, global sMBF (1.14 mL/min/g to 1.5 mL/min/g) and MPR (1.9 to 2.0) |

| 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.09.798 | M. Konigstein | Observational | 23 patients with:

| CSR implantation and observation for 4 months | Israel | Neovasc | Improvement in CCS class (from 3 to 2), CFR (1.7 ± 0.5 to 2.9 ± 1, p < 0.001), IMR (31 ± 10 to 22 ± 16, p = 0.02), 6MWT (303 to 345, p = 0.04) and all SAQ domains (p < 0.01) |

| 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.09.816 | J. M. Paradis | Observational | 11 patients including:

| CSR implantation and observation for 6 months | A-Flux | Improvement in CCS class and all SAQ domains at 30 days, 3 months and 6 months (p < 0.01) | |

| 10.33963/v.kp.98104 | P. Rola | Case report | 65-year-old male patient with CCS3 despite 6 months of optimal anti-anginal therapy with CMD | - | Poland | Improvement in CFR (2.2 to 4.1), IMR (46 to 11), CCS class (3 to 1), 6MWT (90 to 300 m), SAQ, EQ-5D, SF-36 | |

| 10.1002/ccd.31070 | C. Servoz | Observational | 10 patients with:

| CSR implantation and direct measurements after | France | Shockwave | Improvement in maximal absolute coronary flow (106 ± 41 to 139 ± 46, p = 0.039), minimal microvascular resistance (796 ± 508 to 644 ± 326, p = 0.027) and CCS class (3.4 ± 0.5 to 1.7 ± 1.0, p = 0.004—after one month) |

| 10.1161/circinterventions.123.013481 | M. Tebaldi | Observational | 24 patients with:

| CSR implantation and observation for 12 months | Italy | Neovasc | Improvement in primary endpoint—IMR (33.35 ± 19.88 to 15.42 ± 11.36, p < 0.001), CFR (2.46 ± 1.52 to 4.20 ± 2.52, p = 0.007), RRR (2.81 ± 2.31 to 4.75 ± 2.88, p = 0.004), CCS class, and SAQ angina frequence, angina stability, QoL and summary score |

| 10.1016/j.jcin.2024.09.018 | D. Tyron | Observational | 30 patients with:

| CSR implantation and observation for 120 days | United States | Neovasc | Improvement in CFR in response to adenosine [2.1 (1.95–2.30) to 2.7 (2.45–2.95), p = 0.0019], percent change in coronary artery blood flow in response to acetylcholine [11.0 (20.15 to 5.85) to 11.5 (4.82 to 39.29), p = 0.0420], hyperemic microvascular resistance [1.45 (1.05–1.98) to 1.86 (1.44–2.35), p = 0.0420], CCS class [4.0 (3.25–4.0) to 2.0 (2.0–3.0), p < 0.001] and SAQ results (all p < 0.01) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tomaniak, M.; Bednarek, A.; Włodarczak, A. Coronary Sinus Reduction for Refractory Angina Caused by Microvascular Dysfunction—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010291

Tomaniak M, Bednarek A, Włodarczak A. Coronary Sinus Reduction for Refractory Angina Caused by Microvascular Dysfunction—A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):291. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010291

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomaniak, Mariusz, Adrian Bednarek, and Adrian Włodarczak. 2026. "Coronary Sinus Reduction for Refractory Angina Caused by Microvascular Dysfunction—A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010291

APA StyleTomaniak, M., Bednarek, A., & Włodarczak, A. (2026). Coronary Sinus Reduction for Refractory Angina Caused by Microvascular Dysfunction—A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010291