Hyperfibrinolysis During Caesarean Section and Vaginal Delivery: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study in the Delivery Room

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

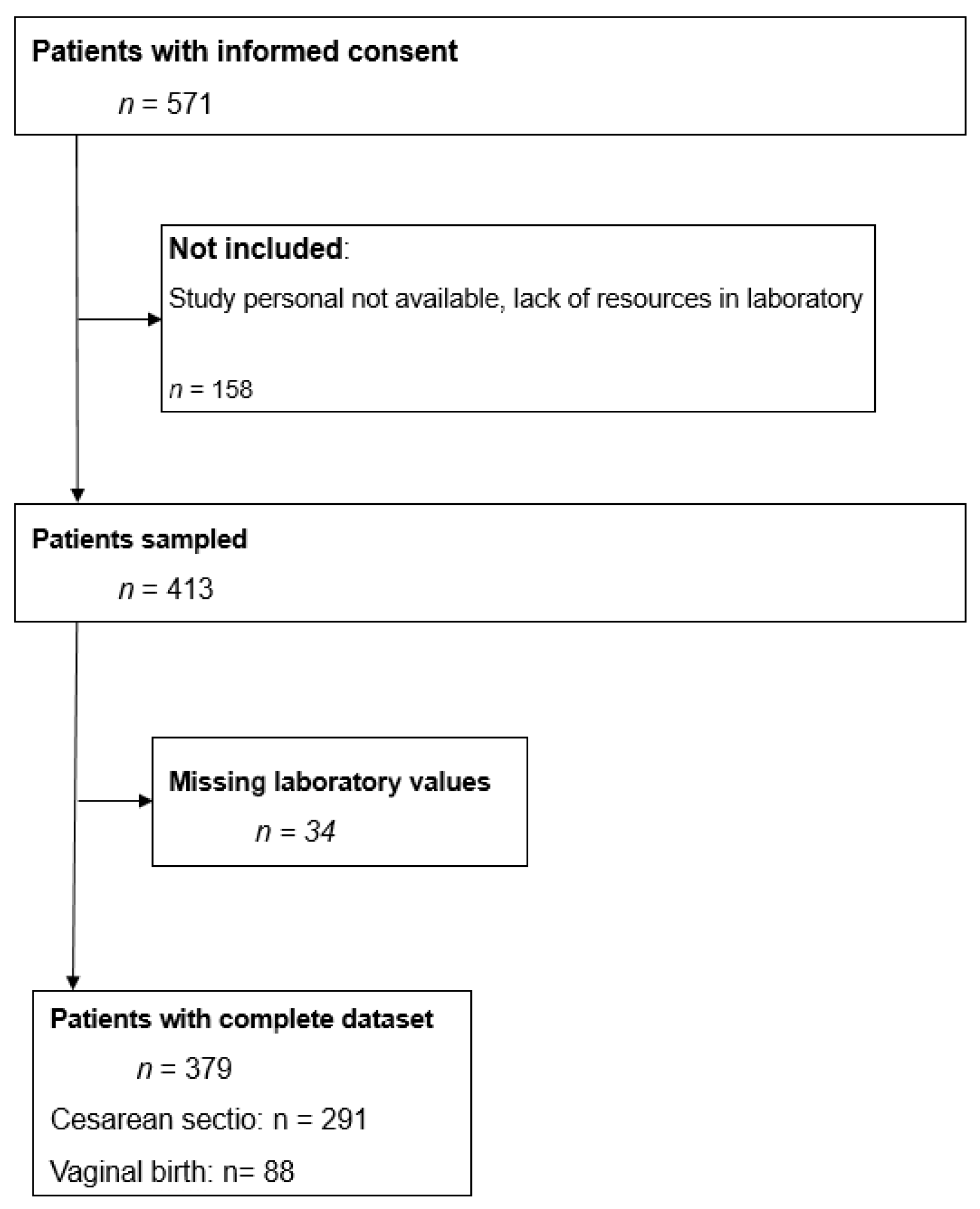

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Objectives

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Subjects

3.2. Primary Outcome: Incidence of Hyperfibrinolysis

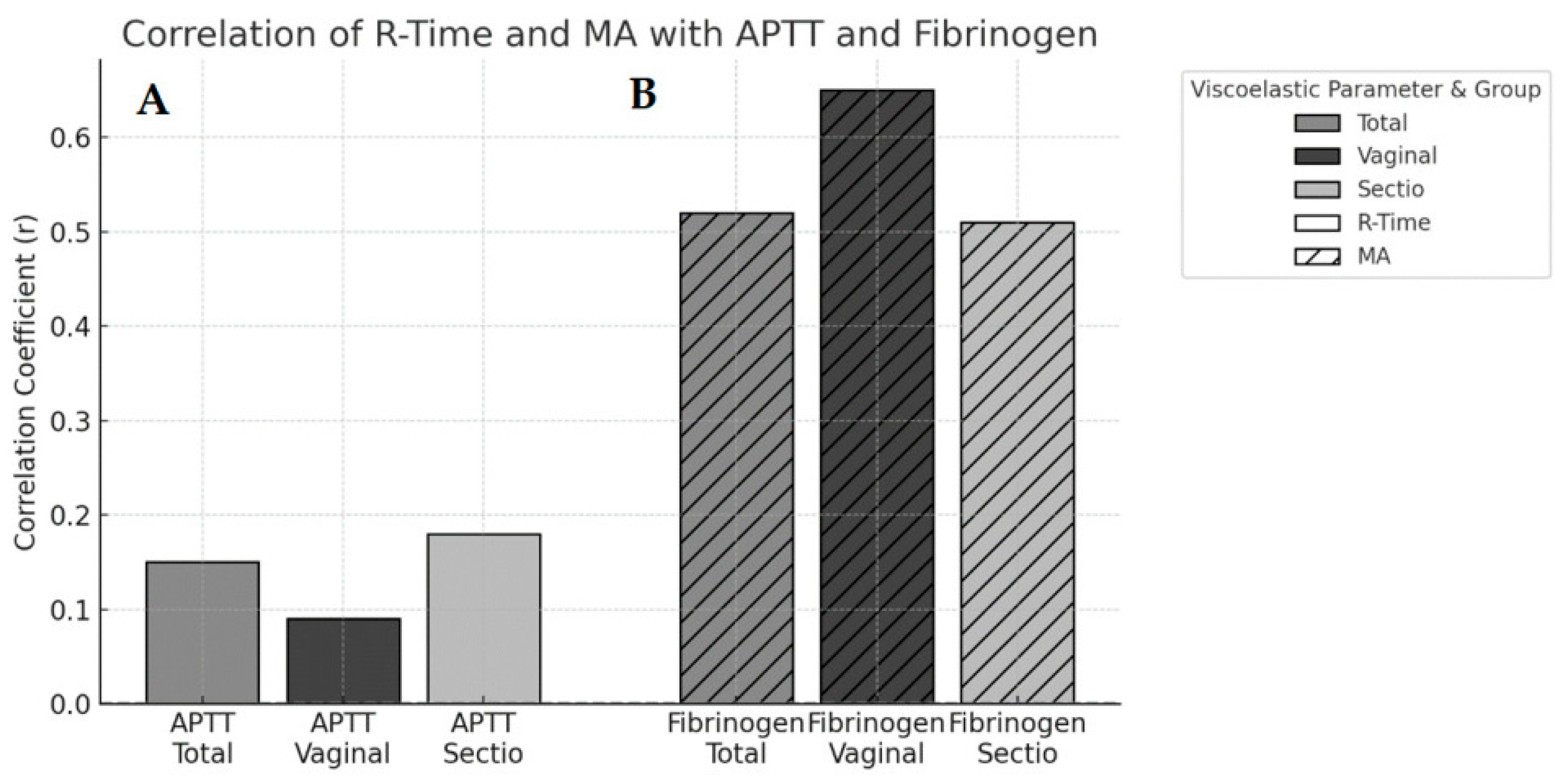

3.3. Secondary Outcomes: Correlation Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gruneberg, D.; Braun, P.; Schöchl, H.; Nachtigall-Schmitt, T.; von der Forst, M.; Tourelle, K.; Dietrich, M.; Wallwiener, M.; Wallwiener, S.; Weigand, M.A.; et al. Fibrinolytic potential as a risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1208103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborators, W.T. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): An international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienstock, J.L.; Eke, A.C.; Hueppchen, N.A. Postpartum Hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1635–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. A Roadmap to Combat Postpartum Haemorrhage Between 2023 and 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, W.; Blum, J.; Vogel, J.; Souza, J.; Gülmezoglu, A.; Winikoff, B. on behalf of the WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health Research Network. Postpartum haemorrhage management, risks, and maternal outcomes: Findings from the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 121, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gao, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, X.; He, J.; Tang, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Postpartum Hemorrhage in China: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 673500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta-Rastelli, C.M.; Friedman, A.M.; Sobhani, N.C.; Arditi, B.; Goffman, D.; Wen, T. Postpartum Hemorrhage Trends and Outcomes in the United States, 2000–2019. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.; Dahhou, M.; Vallerand Dm Liston, R.; Joseph, K.S. Risk Factors for Postpartum Hemorrhage: Can We Explain the Recent Temporal Increase? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2011, 33, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGGG. S2k-Leitlinie Peripartale Blutungen, Diagnostik und Therapie. 2022. Available online: https://register.awmf.org/de/leitlinien/detail/015-063 (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Gallos, I.D.; Papadopoulou, A.; Man, R.; Athanasopoulos, N.; Tobias, A.; Price, M.J.; Williams, M.J.; Diaz, V.; Pasquale, J.; Chamillard, M.; et al. Uterotonic agents for preventing postpartum haemorrhage: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 4, CD011689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, S.D.; Abraham, R. Role of Prophylactic Tranexamic Acid in Reducing Blood Loss during Elective Caesarean Section: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, Qc17–Qc21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentilhes, L.; Winer, N.; Azria, E.; Sénat, M.V.; Le Ray, C.; Vardon, D.; Perrotin, F.; Desbrière, R.; Fuchs, F.; Kayem, G.; et al. Tranexamic Acid for the Prevention of Blood Loss after Vaginal Delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentilhes, L.; Sénat, M.V.; Le Lous, M.; Winer, N.; Rozenberg, P.; Kayem, G.; Verspyck, E.; Fuchs, F.; Azria, E.; Gallot, D.; et al. Tranexamic Acid for the Prevention of Blood Loss after Cesarean Delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herkommer, M.; Geisler, T. Verfahren zur Messung der Thrombozytenfunktion: Pro und kontra. Kardiol. Up2date 2010, 6, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, O.; Jeppsson, A.; Hellgren, M. Major obstetric haemorrhage: Monitoring with thromboelastography, laboratory analyses or both? Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2014, 23, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekelund, K.; Hanke, G.; Stensballe, J.; Wikkelsøe, A.; Albrechtsen, C.K.; Afshari, A. Hemostatic resuscitation in postpartum hemorrhage—A supplement to surgery. Acta Obstet. Et Gynecol. Scand. 2015, 94, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.S.; Devenie, G.; Powell, M. Point-of-Care Testing of Coagulation and Fibrinolytic Status during Postpartum Haemorrhage: Developing a Thrombelastography®-Guided Transfusion Algorithm. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2012, 40, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, D.; DiNardo, J.A. TEG and ROTEM: Technology and clinical applications. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnolds, D.E.; Scavone, B.M. Thromboelastographic Assessment of Fibrinolytic Activity in Postpartum Hemorrhage: A Retrospective Single-Center Observational Study. Anesth. Analg. 2020, 131, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, I.; Shakur, H.; Fawole, B.; Kuti, M.; Olayemi, O.; Bello, A.; Ogunbode, O.; Kotila, T.; Aimakhu, C.O.; Olutogun, T.; et al. Haematological and fibrinolytic status of Nigerian women with post-partum haemorrhage. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, C.R.; Walenga, J.; Mangogna, L.C.; Fareed, J. Neonatal and maternal fibrinolysis: Activation at time of birth. Am. J. Hematol. 1985, 19, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Takeda, J.; Makino, S. Hemostasis for Massive Hemorrhage during Cesarean Section. In Recent Advances in Cesarean Delivery; Schmolzer, G., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bremme, K.A. Haemostatic changes in pregnancy. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2003, 16, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amgalan, A.; Allen, T.; Othman, M.; Ahmadzia, H.K. Systematic review of viscoelastic testing (TEG/ROTEM) in obstetrics and recommendations from the women’s SSC of the ISTH. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1813–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huissoud, C.; Carrabin, N.; Benchaib, M.; Fontaine, O.; Levrat, A.; Massignon, D.; Touzet, S.; Rudigoz, R.C.; Berland, M. Coagulation assessment by rotation thrombelastometry in normal pregnancy. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 101, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLintock, C. Prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: Focus on hematological aspects of management. Hematology 2020, 2020, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 379) | Vaginal Delivery (n = 88) | Caesarean Section (n = 291) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 32.2 (IQR 29.2–35.8) | 31.0 (IQR 26.5–33.7) | 32.6 (IQR 29.7–36.4) | 0.0001 |

| Gestation age (week + day) | 38 + 6 (IQR 37 + 6–39 + 5) | 40 + 1 (IQR 39 + 4–40 + 4) | 38 + 4 (IQR 37 + 4–39 + 0) | <0.0001 |

| BMI before pregnancy | 28.2 (IQR 24.9–32.0) | 27.1 (IQR 24.5–29.8) | 28.7 (IQR 25.0–32.9) | 0.023 |

| Gemini (n=) | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Preterm birth (n=) | 20 | 0 | 20 | |

| Red blood cells | ||||

|

Hb (g/dL) immediately postpartum | 11.3 (IQR 10.6–12.2) | 12.2 (IQR 10.3–12.9) | 11.3 (IQR 10.6–12.0) | |

|

Hb-drop > 2 (n=) at delivery room discharge | 11 | 4 | 7 | |

| TEG | ||||

| R-Time (s) | 230.00 (IQR 200.00–275.00) | 245.00 (IQR 211.25–283.75) | 225.00 (IQR 195.00–270.00) | 0.068 |

| MA (mm) | 72.3 (IQR 70.1–74.2) | 71.8 (IQR 69.95–73.95) | 72.3 (IQR 70.10–74.20) | 0.467 |

| LY30 (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.489 |

| Quantitative coagulation values | ||||

| APTT (s) | 25.9 (IQR 24.1–28.0) | 25.35 (IQR 23.77–27.42) | 26.00 (IQR 24.40–28.10) | 0.029 |

| PT | 107.0 (IQR 99.0–114.0) | 109.0 (IQR 100.0–115.0) | 106.0 (IQR 98.0–112.0) | 0.07 |

| DD | 2.47 (IQR 1.70–3.84) | 2.80 (IQR 1.94–4.44) | 2.36 (IQR 1.58–3.32) | 0.002 |

| Fibrinogen | 458.00 (IQR 402.50–516.00) | 490.50 (IQR 436.75–566.75) | 449.00 (IQR 98.00–112.00) | <0.0001 |

| Viscoelastic Parameter | Coagulation Marker | Cohort | r | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-time | aPTT | Total | 0.15 | 0.04–0.25 | >0.05 |

| R-time | aPTT | Caesarean section | 0.19 | 0.07–0.31 | <0.01 |

| R-time | aPTT | Vaginal delivery | 0.04 | −0.17–0.25 | >0.05 |

| MA | Fibrinogen | Total | 0.52 | 0.45–0.58 | <0.001 |

| MA | Fibrinogen | Caesarean section | 0.51 | 0.49–0.77 | <0.001 |

| MA | Fibrinogen | Vaginal delivery | 0.65 | 0.43–0.58 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zoidl, P.; Honnef, G.; Eichinger, M.; Eichlseder, M.; Heuschneider, L.; Hammer, S.; Schreiber, N.; Prüller, F.; Weiss, E.C.; Amtmann, B.; et al. Hyperfibrinolysis During Caesarean Section and Vaginal Delivery: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study in the Delivery Room. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010027

Zoidl P, Honnef G, Eichinger M, Eichlseder M, Heuschneider L, Hammer S, Schreiber N, Prüller F, Weiss EC, Amtmann B, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis During Caesarean Section and Vaginal Delivery: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study in the Delivery Room. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleZoidl, Philipp, Gabriel Honnef, Michael Eichinger, Michael Eichlseder, Lioba Heuschneider, Sascha Hammer, Nikolaus Schreiber, Florian Prüller, Eva Christine Weiss, Bettina Amtmann, and et al. 2026. "Hyperfibrinolysis During Caesarean Section and Vaginal Delivery: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study in the Delivery Room" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010027

APA StyleZoidl, P., Honnef, G., Eichinger, M., Eichlseder, M., Heuschneider, L., Hammer, S., Schreiber, N., Prüller, F., Weiss, E. C., Amtmann, B., & Bornemann-Cimenti, H. (2026). Hyperfibrinolysis During Caesarean Section and Vaginal Delivery: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study in the Delivery Room. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010027