Phase-Related Resting Energy Expenditure in Critically Ill Adults: Metabolic Phenotypes and Determinants of Weight-Normalized Indices—A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

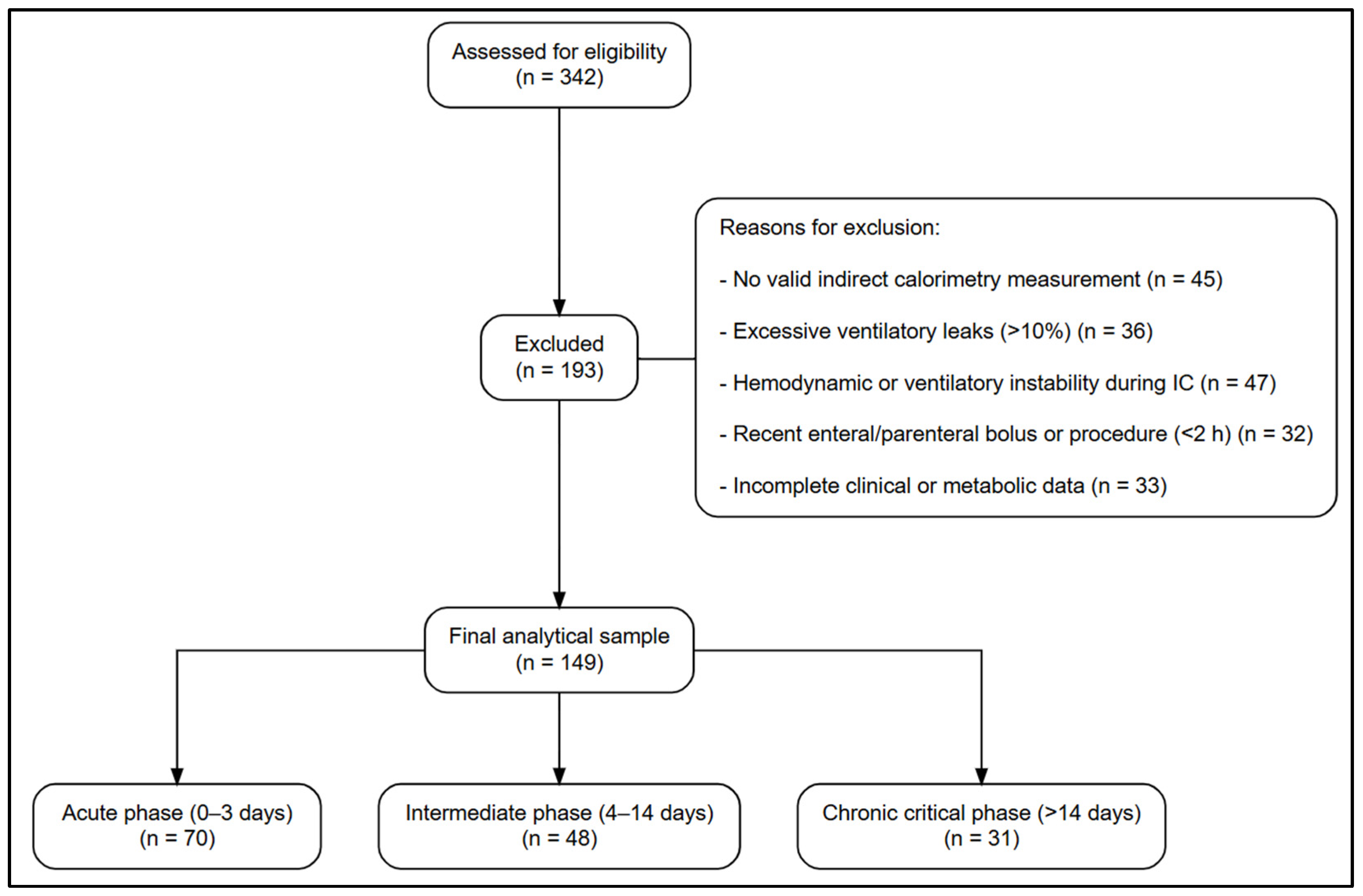

2.2. Population and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Sources and Measurement Procedures

2.4. Variables and Operational Definitions

2.5. Metabolic Categorization

2.6. Data Preparation and Transformation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.7.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.7.2. Comparative Analysis Between Phases

2.7.3. Bivariate Correlation Analysis

2.7.4. Multivariable Modeling

2.7.5. Model Diagnostics and Assumption Testing

2.7.6. Statistical Threshold and Software

2.7.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Phase-Dependent Variation in Metabolic and Bioenergetic Parameters

3.3. Correlation Between REE and Clinical or Metabolic Parameters

3.4. Multivariable Modeling

3.5. Model Performance and Validation

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanistic Insights

4.2. Clinical Implications

- Operationalizing IC. Where a full IC is unavailable, validated surrogates (e.g., ultrasound models) may assist, though accuracy declines in early acute phases or low BMI—hence IC remains preferred [34].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tatucu-Babet, O.A.; Fetterplace, K.; Lambell, K.; Miller, E.; Deane, A.M.; Ridley, E.J. Is Energy Delivery Guided by Indirect Calorimetry Associated with Improved Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatucu-Babet, O.A.; King, S.J.; Zhang, A.Y.; Lambell, K.J.; Tierney, A.C.; Nyulasi, I.B.; McGloughlin, S.; Pilcher, D.; Bailey, M.; Paul, E.; et al. Measured energy expenditure according to the phases of critical illness: A descriptive cohort study. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2025, 49, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reignier, J.; Rice, T.W.; Arabi, Y.M.; Casaer, M. Nutritional Support in the ICU. BMJ 2025, 388, e077979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.; Hiesmayr, M.; Mayer, K.; Montejo-Gonzalez, J.C.; Pichard, C.; Preiser, J.C.; et al. ESPEN practical and partially revised guideline: Clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1671–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonen, H.P.F.X.; Beckers, K.J.H.; van Zanten, A.R.H. Energy expenditure and indirect calorimetry in critical illness and convalescence: Current evidence and practical considerations. J. Intensive Care 2021, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byerly, S.E.; Yeh, D.D. The Role of Indirect Calorimetry in Care of the Surgical Patient. Curr. Surg. Rep. 2022, 10, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sungurtekin, H.; Karakuzu, S.; Serin, S. Energy Expenditure in Mechanically Ventilated Patients: Indirect Calorimetry vs Predictive Equations. Dahili Cerrahi Bilim. Yoğun Bakım Derg. 2019, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, G.; Thomas, S.; Dunlea, T.; Jimenez, A.N.; Eiferman, D.; Nahikian-Nelms, M.; Roberts, K.M. Comparison of predictive equations and indirect calorimetry in critical care: Does the accuracy differ by body mass index classification? Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2023, 38, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraki, J.; Paulsen, G.; Garthe, I.; Slater, G.; Areta, J.L. Reliability of resting metabolic rate between and within day measurements using the Vyntus CPX system and comparison against predictive formulas. Nutr. Health 2023, 29, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.Y.; Zheng, W.H.; Zhou, H.; Xu, Y.; Huang, H.B. Energy delivery guided by indirect calorimetry in critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Izumino, H.; Takatani, Y.; Tsutsumi, R.; Suzuki, T.; Tatsumi, H.; Yamamoto, R.; Sato, T.; Miyagi, T.; Miyajima, I.; et al. Effects of Energy Delivery Guided by Indirect Calorimetry in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasyluk, W.; Fiut, R.; Świetlicka, I.; Szukała, M.; Zwolak, A.; Jonckheer, J.; Dąbrowski, W. Time-course changes in energy expenditure in sepsis: A prospective observational study. Ann. Intensive Care 2025, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Heer, G.; Burdelski, C.; Ammon, C.; Doliwa, A.L.; Hilbert, P.; Kluge, S.; Grensemann, J. Energy Expenditure in Critically Ill Obese Patients—A Prospective Observational Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldsman, L.; Richards, G.A.; Lombard, C.; Blaauw, R. Course of measured energy expenditure over the first 10 days of critical illness: A nested prospective study in an adult surgical ICU. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 65, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonen, H.P.F.X.; Hermans, A.J.H.; Bos, A.E.; Snaterse, I.; Stikkelman, E.; van Zanten, F.J.L.; van Exter, S.H.; van de Poll, M.C.; van Zanten, A.R. Resting energy expenditure measured by indirect calorimetry in mechanically ventilated patients during ICU stay and post-ICU hospitalization: A prospective observational study. J. Crit. Care 2023, 78, 154361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waele, E.; Jonckheer, J.; Wischmeyer, P.E. Indirect calorimetry in critical illness: A new standard of care? Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2021, 27, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koekkoek, W.A.C.; Xiaochen, G.; van Dijk, D.; van Zanten, A.R.H. Resting energy expenditure by indirect calorimetry versus the ventilator-VCO2 derived method in critically ill patients: The DREAM-VCO2 prospective comparative study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 39, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tah, P.C.; Lee, Z.Y.; Poh, B.K.; Abdul Majid, H.; Hakumat-Rai, V.R.; Mat Nor, M.B.; Kee, C.C.; Zaman, M.K.; Hasan, M.S. A Single-Center Prospective Observational Study Comparing Resting Energy Expenditure in Different Phases of Critical Illness: Indirect Calorimetry Versus Predictive Equations. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 48, e380–e390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landes, S.; McClave, S.A.; Frazier, T.H.; Lowen, C.C.; Hurt, R.T. Indirect Calorimetry: Is it Required to Maximize Patient Outcome from Nutrition Therapy? Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, I.; Asada, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Hayase, N.; Hiruma, T.; Doi, K. Changes in carbon dioxide production and oxygen uptake evaluated using indirect calorimetry in mechanically ventilated patients with sepsis. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Granda, A.; Schollenberger, A.; Haap, M.; Riessen, R.; Bischoff, S.C. Optimization of Nutrition Therapy with the Use of Calorimetry to Determine and Control Energy Needs in Mechanically Ventilated Critically Ill Patients: The ONCA Study, a Randomized, Prospective Pilot Study. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2019, 43, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederer, L.E.; Miller, H.; Haines, K.L.; Molinger, J.; Whittle, J.; MacLeod, D.B.; McClave, S.A.; Wischmeyer, P.E. Prolonged progressive hypermetabolism during COVID-19 hospitalization undetected by common predictive energy equations. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 45, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preau, S.; Vodovar, D.; Jung, B.; Lancel, S.; Zafrani, L.; Flatres, A.; Oualha, M.; Voiriot, G.; Jouan, Y.; Joffre, J.; et al. Energetic dysfunction in sepsis: A narrative review. Ann. Intensive Care 2021, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zusman, O.; Theilla, M.; Cohen, J.; Kagan, I.; Bendavid, I.; Singer, P. Resting energy expenditure, calorie and protein consumption in critically ill patients: A retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertzov, B.; Bar-Yoseph, H.; Menndel, Y.; Bendavid, I.; Kagan, I.; Glass, Y.D.; Singer, P. The effect of indirect calorimetry guided isocaloric nutrition on mortality in critically ill patients—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waele, E.; van Zanten, A.R.H. Routine use of indirect calorimetry in critically ill patients: Pros and cons. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, A.; Calicchio, A.; Palmese, S.; Pascarella, S.; Pisapia, B.; Gammaldi, R. Estimating resting energy expenditure in critically ill patients: A retrospective exploratory comparison of predictive equations and Fick-derived Weir estimates in Italy. Acute Crit. Care 2025, 40, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozaki, K.; Yu, P.J.; Zhou, Q.; Cassiere, H.A.; John, S.; Rolston, D.M.; Garg, N.; Li, T.; Johnson, J.; Saeki, K.; et al. Low respiratory quotient correlates with high mortality in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 78, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Martín, J.; Mañas, A.; Alfaro-Acha, A.; García-García, F.J.; Ara, I. Optimization of VO2 and VCO2 outputs for the calculation of resting metabolic rate using a portable indirect calorimeter. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2023, 33, 1648–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, G.; Vicario, F.; Buizza, R. System for continuous metabolic monitoring of mechanically ventilated patients. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1356087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y. Nutritional support in critical care: Estimating resting energy expenditure in the intensive care unit when indirect calorimetry is limited. Acute Crit. Care 2025, 40, 505–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspari, K.; Flechner-Klein, J.; Cohen, T.R.; Wedemire, C. Measured resting energy expenditure and predicted resting energy expenditure based on ASPEN critical care guidelines for nutrition support: An agreement study. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2025, 49, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, C.; Oliveira, A.; Brooks, D.; Newman, A.N.L. The Effects of Inspiratory Muscle Training in Critically ill Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Tan, L.; Zhou, Y.; Peng, W.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, H.; van Zanten, A.R.H.; Zhu, Y. Accuracy of bedside ultrasound for predicting resting energy expenditure in critically ill patients: A feasibility study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | 0–3 Days (N = 70) 1 | 4–14 Days (N = 48) 1 | >14 Days (N = 31) 1 | Overall (N = 149) | p-Value 2 | Effect Size 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 0.711 | — 4 | ||||

| Female | 30 (43%) | 23 (48%) | 12 (39%) | 65 (44%) | ||

| Male | 40 (57%) | 25 (52%) | 19 (61%) | 84 (56%) | ||

| Metabolic state | 0.002 | — | ||||

| Hypometabolic | 45 (64%) | 15 (31%) | 11 (35%) | 71 (48%) | ||

| Normometabolic | 11 (16%) | 12 (25%) | 5 (16%) | 28 (19%) | ||

| Hypermetabolic | 14 (20%) | 21 (44%) | 15 (48%) | 50 (34%) | ||

| Age (years) | 66 (55, 74) | 68 (51, 77) | 66 (56, 73) | 66 (54, 74) | 0.912 | ε2 ≈ 0.000 |

| Weight (kg) | 87 (75, 100) | 81 (70, 93) | 85 (80, 100) | 85 (75, 98) | 0.163 | ε2 = 0.011 |

| Height (m) | 1.65 (1.60, 1.74) | 1.67 (1.60, 1.75) | 1.70 (1.60, 1.77) | 1.67 (1.60, 1.75) | 0.353 | η2 = 0.014 |

| Ideal body weight (kg) | 62.7 (57.2, 67.0) | 61.7 (57.2, 67.9) | 65.4 (58.7, 69.2) | 62.7 (57.2, 67.6) | 0.396 | η2 = 0.013 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32 (28, 35) | 29 (25, 35) | 32 (26, 39) | 31 (26, 36) | 0.238 | ε2 = 0.006 |

| APACHE II | 15 (9, 21) | 16 (11, 21) | 14 (9, 20) | 15 (9, 21) | 0.858 | ε2 ≈ 0.000 |

| SOFA at measurement | 5.0 (1.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 9.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 9.0) | 6.0 (2.0, 8.5) | 0.119 | ε2 = 0.016 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 4.00 (2.00, 6.00) | 2.00 (0.00, 4.00) | 2.00 (1.00, 4.00) | 3.00 (1.00, 5.00) | 0.005 | ε2 = 0.058 |

| REE (kcal/day) | 1664 (1505, 1964) | 1869 (1539, 2239) | 2074 (1603, 2412) | 1781 (1523, 2177) | 0.024 | ε2 = 0.037 |

| REE/kg (kcal·kg−1·day−1) | 19 (17, 23) | 22 (19, 30) | 21 (17, 28) | 21 (17, 26) | 0.006 | ε2 = 0.057 |

| REE/IBW (kcal·kg−1·day−1) | 28 (25, 31) | 31 (26, 36) | 32 (25, 38) | 29 (25, 34) | 0.024 | ε2 = 0.037 |

| RQ (VCO2/VO2) | 0.80 (0.76, 0.91) | 0.96 (0.84, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.08) | 0.89 (0.79, 1.00) | <0.001 | ε2 = 0.240 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 238 (215, 287) | 257 (213, 322) | 276 (222, 330) | 250 (217, 310) | 0.313 | ε2 = 0.002 |

| VCO2 (mL/min) | 204 (175, 243) | 249 (200, 301) | 261 (217, 315) | 218 (188, 282) | <0.001 | ε2 = 0.125 |

| VO2/weight (mL·min−1·kg−1) | 2.79 (2.44, 3.28) | 3.11 (2.59, 4.05) | 2.79 (2.33, 3.78) | 2.85 (2.47, 3.65) | 0.066 | ε2 = 0.024 |

| VO2/IBW (mL·min−1·kg−1) | 3.95 (3.48, 4.63) | 4.29 (3.50, 5.07) | 4.28 (3.46, 5.09) | 4.03 (3.48, 4.90) | 0.357 | ε2 ≈ 0.000 |

| VCO2/weight (mL·min−1·kg−1) | 2.29 (1.87, 2.68) | 3.25 (2.49, 3.89) | 2.72 (2.26, 3.77) | 2.57 (2.08, 3.44) | <0.001 | ε2 = 0.132 |

| VCO2/IBW (mL·min−1·kg−1) | 3.26 (2.85, 3.81) | 4.00 (3.50, 4.86) | 4.42 (3.28, 4.73) | 3.60 (3.01, 4.46) | <0.001 | ε2 = 0.148 |

| Predictor | β | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 54 | −163, 271 | 0.60 |

| Phase of illness | |||

| • Linear component (fase.L) | −107 | −179, −35 | 0.004 |

| • Quadratic component (fase.Q) | 27 | −38, 92 | 0.40 |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | 8.0 | 3.1, 13 | 0.002 |

| SOFA score | −14 | −26, −2.4 | 0.018 |

| APACHE II score | 1.1 | −4.3, 6.5 | 0.70 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | −4.5 | −19, 10 | 0.50 |

| Carbon dioxide production (VCO2, mL/min) | 6.8 | 6.2, 7.4 | <0.001 |

| Predictor | β | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 19 | 15, 24 | <0.001 |

| Phase of illness | |||

| • Linear component (fase.L) | −0.23 | −1.2, 0.72 | 0.60 |

| • Quadratic component (fase.Q) | −0.74 | −1.6, 0.10 | 0.084 |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | 0.24 | 0.17, 0.32 | <0.001 |

| SOFA score | 0.00 | −0.12, 0.13 | >0.90 |

| Respiratory quotient (RQ) | −15 | −18, −11 | <0.001 |

| Carbon dioxide production (VCO2, mL/min) | 0.07 | 0.06, 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Metabolic phenotype | |||

| • Normometabolic (reference) | — | — | — |

| • Hypometabolic | −2.8 | −4.1, −1.5 | <0.001 |

| • Hypermetabolic | 3.2 | 1.7, 4.7 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chapela, S.; Cagua-Ordoñez, J.; Angamarca-Iguago, J.; Tettamanti, D.; Kecskes, C.; Asparch, J.; Gutierrez, F.J.; Llobera, N.; Rella, M.; Montalván, M.; et al. Phase-Related Resting Energy Expenditure in Critically Ill Adults: Metabolic Phenotypes and Determinants of Weight-Normalized Indices—A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010237

Chapela S, Cagua-Ordoñez J, Angamarca-Iguago J, Tettamanti D, Kecskes C, Asparch J, Gutierrez FJ, Llobera N, Rella M, Montalván M, et al. Phase-Related Resting Energy Expenditure in Critically Ill Adults: Metabolic Phenotypes and Determinants of Weight-Normalized Indices—A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010237

Chicago/Turabian StyleChapela, Sebastián, Jaen Cagua-Ordoñez, Jaime Angamarca-Iguago, Daniel Tettamanti, Claudia Kecskes, Jesica Asparch, Facundo Javier Gutierrez, Natalia Llobera, Mariana Rella, Martha Montalván, and et al. 2026. "Phase-Related Resting Energy Expenditure in Critically Ill Adults: Metabolic Phenotypes and Determinants of Weight-Normalized Indices—A Retrospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010237

APA StyleChapela, S., Cagua-Ordoñez, J., Angamarca-Iguago, J., Tettamanti, D., Kecskes, C., Asparch, J., Gutierrez, F. J., Llobera, N., Rella, M., Montalván, M., Reberendo, M. J., Pozo, M. O., Álvarez-Córdova, L., & Simancas-Racines, D. (2026). Phase-Related Resting Energy Expenditure in Critically Ill Adults: Metabolic Phenotypes and Determinants of Weight-Normalized Indices—A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010237