The Prognostic Value of Biomarkers in Patients Diagnosed with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SBP | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis |

| BAR | Blood urea nitrogen/albumin ratio |

| RAR | Red cell distribution width/albumin ratio |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristics |

| RDW | Red blood cell distribution width |

| PMN | Polymorphonuclear |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

References

- Long, B.; Gottlieb, M. Emergency medicine updates: Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 70, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T.; Li, Q.; Jiang, G.; Tan, H.-Y.; Wu, J.-H.; Qin, S.-Y.; Yu, B.; Jiang, H.-X.; Luo, W. Systematically analysis of decompensated cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis to identify diagnostic and prognostic indexes. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, N.; Salah, M.; Elbaz, S.; Elmetwalli, A.; Elhammady, A.; Abdelkader, E.; Abdelsalam, M.; El-Wakeel, N.; Mansour, M.; Hashem, M.; et al. Neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio is a new diagnostic marker for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A prospective multicenter study. Gut Pathog. 2024, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, S.; Waheed, M.; Vuthaluru, K.; Jaffar, T.; Garlapati, S.; Bseiso, O.; Nousherwani, M.; Saleem, F. Efficacy of Intravenous Albumin for Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Infection Among Patients with Cirrhosis: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials. Cureus 2022, 14, e33124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oblokulov, A.R.; Oblokulova, O.A.; Bahronov, O.O. Laboratory characteristics of patients with liver cirrhosis of virus etiology complicated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Eur. J. Med. Genet. Clin. Biol. 2024, 1, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H.; Oza, F.; Ahmed, K.; Kopel, J.; Aloysius, M.M.; Ali, A.; Dahiya, D.S.; Aziz, M.; Perisetti, A.; Goyal, H. The role of red cell distribution width as a prognostic marker in chronic liver disease: A literature review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebied, A.; Rattanasuwan, T.; Chen, Y.; Khoury, A. Albumin utilization in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 35, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, S.; Ahmed, E.; Roshdy, M.; Abdelazim, O.; Hamdy, L.; Hassan, H. Study of the Role of Novel Biomarkers for Early Detection of SBP. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Fan, C.; Dang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Lv, L.; Lou, J.; Li, L.; Ding, H. Clinical Characteristics and Early Diagnosis of Spontaneous Fungal Peritonitis/Fungiascites in Hospitalized Cirrhotic Patients with Ascites: A Case–Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Würstle, S.; Hapfelmeier, A.; Karapetyan, S.; Studen, F.; Isaakidou, A.; Schneider, T.; Schmid, R.M.; von Delius, S.; Gundling, F.; Burgkart, R.; et al. Differentiation of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis from Secondary Peritonitis in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: Retrospective Multicentre Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.H.; Ho, P.T.; Bui, H.H.; Vo, T.D. Non-Invasive Methods for the Prediction of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in Patients with Cirrhosis. Gastroenterol. Insights 2023, 14, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszecka, J.; Filip, R. Epidemiological Study of Pathogens in Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis in 2017–2024—A Preliminary Report of the University Hospital in South-Eastern Poland. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccauro, V.; Airola, C.; Santopaolo, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R.; Pompili, M. Gut Microbiota and Infectious Complications in Advanced Chronic Liver Disease: Focus on Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Life 2023, 13, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wejnaruemarn, S.; Susantitaphong, P.; Komolmit, P.; Treeprasertsuk, S.; Thanapirom, K. Procalcitonin and presepsin for detecting bacterial infection and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 99506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, W.; Wu, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Teng, W.; Hsieh, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, C.; Hsu, C.; et al. A Validated Composite Score Demonstrates Potential Superiority to MELD-Based Systems in Predicting Short-Term Survival in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis and Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis—A Preliminary Study. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Korbitz, P.; Gallagher, J.; Schmidt, C.; Ingviya, T.; Manatsathit, W. Ascitic calprotectin and lactoferrin for detection of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubhi, N.; Mourad, A.; Tausan, M.; Lewis, D.; Smethurst, J.; Wenlock, R.; Gouda, M.; Bremner, S.; Verma, S. Outcomes after Hospitalisation with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis over a 13-Year Period: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 35, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putri, A.; Supriono, S.; Tonowidjojo, V.; Fitriani, J.; Utama, G.N.; Muthmainah, A.A.; Asrinawati, A.N. Evaluation of C-reactive protein, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and absolute neutrophil count as simple diagnostic markers for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. J. Health Nutr. Res. 2025, 4, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efgan, M.; Acar, H.; Kanter, E.; Kırık, S.; Şahan, T. Role of systemic immune inflammation index, systemic immune response index, neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio in predicting peritoneal culture positivity and prognosis in cases of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis admitted to the emergency department. Medicina 2024, 60, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, I.; Vrioni, G.; Hadziyannis, E.; Alexopoulos, T.; Vasilieva, L.; Tsiriga, A.; Tsiamis, C.; Tsakris, A.; Dourakis, S.P.; Alexopoulou, A. Bacterial DNA is a prognostic factor for mortality in patients who recover from spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2021, 34, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliaz, R.; Ozpolat, T.; Baran, B.; Demir, K.; Kaymakoglu, S.; Besisik, F.; Akyuz, F. Predicting mortality in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis using routine inflammatory and biochemical markers. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 30, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.; Ju, S.; Lee, S.; Cho, Y.J.; Lee, J.D.; Kim, H.C. Red cell distribution width/albumin ratio is associated with 60-day mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Infect. Dis. 2020, 52, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pang, S.; Huang, H.; Lu, Y.; Tang, T.; Wu, J.; Chen, M. Association between red cell distribution width-to-albumin ratio and all-cause mortality in critically ill cirrhotic patients with sepsis: A retrospective analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1610726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huo, J.; Chen, G.; Yang, K.; Huang, Z.; Peng, L.; Xu, J.; Jiang, J. Association between red blood cell distribution width to albumin ratio and prognosis of patients with sepsis: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1019502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.; Heo, M.; Lee, S.; Jeong, Y.Y.; Lee, J.D.; Yoo, J.-W. Clinical usefulness of red cell distribution width/albumin ratio to discriminate 28-day mortality in critically ill patients with pneumonia receiving invasive mechanical ventilation compared with lactate/albumin ratio: A retrospective cohort study. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeimi Bafghi, N.; Torabi, M.; Ashkar, F.; Mirzaee, M. Diagnostic accuracy of mean platelet volume in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis presented to the emergency department. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 16, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xia, H.; Lin, J.; Liu, M.; Lai, J.; Yang, Z.; Qiu, L. Association of blood urea nitrogen to albumin ratio with mortality in acute pancreatitis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 97891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulloque-Badaracco, J.; Alarcón-Braga, E.; Hernández-Bustamante, E.; Al-Kassab-Córdova, A.; Mosquera-Rojas, M.D.; Ulloque-Badaracco, R.R.; Huayta-Cortez, M.A.; Maita-Arauco, S.H.; Herrera-Añazco, P.; Benites-Zapata, V.A. Fibrinogen-to-albumin ratio and blood urea nitrogen-to-albumin ratio in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.; Kwon, H.; Jeong, H.; Park, J.; Min, K. Blood urea nitrogen to albumin ratio is associated with cerebral small vessel diseases. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 54919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ye, B.; Shen, J. Prognostic value of albumin-related ratios in HBV-associated decompensated cirrhosis. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, N.N.G.K.; Mariadi, I.K.; Dewi, N.L.P.Y.; Pamungkas, K.M.N.; Dewi, P.I.S.L.; Sindhughosa, D.A. A novel predictor compared to the model for end-stage liver disease and Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores for predicting 30-day mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis. Cureus 2025, 17, e81446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnock, B.; Afarian, H.; Minnigan, H.; Butler, J.; Hendey, G.W. Physician clinical impression does not rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients undergoing emergency department paracentesis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2008, 52, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Age | 63.44 ± 13.16 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 49 (43.8) |

| Male | 63 (56.3) |

| WBC | 15.76 ± 9.19 |

| NEU | 14.29 ± 11.19 |

| LYM | 1.08 ± 0.74 |

| MONO | 0.97 ± 0.68 |

| HGB | 13.25 ± 16.32 |

| HCT | 31.9 ± 5.56 |

| PLT | 262.67 ± 175.95 |

| PCT | 0.28 ± 0.17 |

| RDW | 17.79 ± 3.13 |

| BUN | 43.32 ± 29.29 |

| CRE | 1.65 ± 1.18 |

| AST | 89.15 ± 137.04 |

| ALT | 49.42 ± 109.23 |

| ALB | 24.69 ± 5.77 |

| T. BIL | 3.58 ± 4.76 |

| D. BIL | 2.11 ± 3.46 |

| CRP | 147.24 ± 107.17 |

| Emergency Department Outcome | |

| Ward | 59 (56.7) |

| ICU | 45 (43.3) |

| Discharge | 63 (56.3) |

| Deceased | 49 (43.8) |

| RDW/ALB | 0.76 ± 0.26 |

| BUN/ALB | 1.84 ± 1.32 |

| NLR | 25.36 ± 67.52 |

| Ward | ICU | Test Statistics | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.85 ± 12.77 | 60.62 ± 13.53 | 1.569 | 0.117 † |

| Gender | 0.416 | 0.519 † | ||

| Female | 26 (60.5) | 17 (39.5) | ||

| Male | 33 (54.1) | 28 (45.9) | ||

| WBC | 15.76 ± 9.62 | 16.91 ± 8.96 | 0.932 | 0.352 † |

| NEU | 13.56 ± 9.05 | 16.58 ± 13.78 | 1.322 | 0.186 † |

| LYM | 1.03 ± 0.66 | 1.05 ± 0.68 | 0.059 | 0.953 † |

| MONO | 1 ± 0.72 | 0.99 ± 0.67 | 0.075 | 0.940 † |

| HGB | 10.56 ± 1.77 | 17.4 ± 25.24 | 1.372 | 0.170 † |

| HCT | 31.94 ± 4.98 | 32.06 ± 5.98 | 0.112 | 0.911 † |

| PLT | 297.97 ± 193.6 | 205.71 ± 135.62 | 2.611 | 0.009 † |

| PCT | 0.3 ± 0.18 | 0.23 ± 0.15 | 2.161 | 0.031 † |

| RDW | 17.74 ± 3.28 | 18.08 ± 3.09 | 0.515 | 0.606 † |

| BUN | 37.49 ± 24.91 | 52.96 ± 33.65 | 2.264 | 0.024 † |

| CRE | 1.45 ± 0.8 | 2.01 ± 1.54 | 1.811 | 0.070 † |

| AST | 71.02 ± 93.59 | 122.84 ± 181.29 | 2.145 | 0.032 † |

| ALT | 45.25 ± 83.57 | 60.89 ± 143.21 | 1.139 | 0.255 † |

| ALB | 24.81 ± 5.78 | 24.42 ± 5.53 | 0.687 | 0.492 † |

| T. BIL | 2.28 ± 2.62 | 5.72 ± 6.26 | 3.042 | 0.002 † |

| D. BIL | 1.26 ± 1.79 | 3.47 ± 4.7 | 2.581 | 0.010 † |

| CRP | 129.3 ± 88.79 | 181.23 ± 124.54 | 2.165 | 0.030 † |

| Outcome | 15.092 | 0.001 † | ||

| Discharge | 41 (74.5) | 14 (25.5) | ||

| Deceased | 18 (36.7) | 31 (63.3) | ||

| RDW/ALB | 0.76 ± 0.27 | 0.78 ± 0.26 | 0.246 | 0.806 † |

| BUN/ALB | 1.62 ± 1.35 | 2.24 ± 1.28 | 2.602 | 0.009 † |

| NLR | 16.62 ± 1.77 | 40.06 ± 15.54 | 0.594 | 0.441 |

| Discharge | Deceased | Test Statistics | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 63.41 ± 12.34 | 63.47 ± 14.27 | 0.258 | 0.796 † |

| Gender | 0.028 | 0.867 † | ||

| Female | 28 (57.1) | 21 (42.9) | ||

| Male | 35 (55.6) | 28 (44.4) | ||

| WBC | 14.99 ± 8.9 | 16.75 ± 9.56 | 1.132 | 0.258 † |

| NEU | 12.62 ± 8.48 | 16.44 ± 13.72 | 1.830 | 0.067 † |

| LYM | 1.22 ± 0.81 | 0.9 ± 0.62 | 2.499 | 0.012 † |

| MONO | 0.93 ± 0.55 | 1.03 ± 0.81 | 0.114 | 0.909 † |

| HGB | 11.9 ± 11.02 | 14.99 ± 21.29 | 1.079 | 0.280 † |

| HCT | 31.84 ± 5 | 31.97 ± 6.25 | 0.719 | 0.472 † |

| PLT | 302.51 ± 192.9 | 211.45 ± 136.99 | 2.871 | 0.004 † |

| PCT | 0.31 ± 0.18 | 0.23 ± 0.14 | 2.431 | 0.015 † |

| RDW | 17.08 ± 2.83 | 18.71 ± 3.28 | 2.708 | 0.007 † |

| BUN | 32.02 ± 21.18 | 57.86 ± 31.96 | 4.673 | 0.001 † |

| CRE | 1.35 ± 0.75 | 2.03 ± 1.48 | 2.845 | 0.004 † |

| AST | 58.08 ± 105.08 | 127.84 ± 161.52 | 3.002 | 0.003 † |

| ALT | 40.98 ± 120.57 | 60.27 ± 92.73 | 2.112 | 0.035 † |

| ALB | 25.46 ± 5.91 | 23.68 ± 5.49 | 1.657 | 0.097 † |

| T. BIL | 2.48 ± 3.94 | 5.05 ± 5.38 | 3.156 | 0.002 † |

| D. BIL | 1.37 ± 2.89 | 3.08 ± 3.92 | 2.794 | 0.005 † |

| CRP | 126.38 ± 98.3 | 174.07 ± 113.02 | 2.469 | 0.014 † |

| Emergency Department Outcome | 15.092 | 0.001 † | ||

| Ward | 41 (69.5) | 18 (30.5) | ||

| ICU | 14 (31.1) | 31 (68.9) | ||

| RDW/ALB | 0.71 ± 0.24 | 0.84 ± 0.95 | 2.401 | 0.016 † |

| BUN/ALB | 1.32 ± 0.95 | 2.51 ± 1.44 | 4.550 | 0.001 † |

| NLR | 13.22 ± 9.76 | 40.95 ± 99.89 | 9.650 | 0.030 |

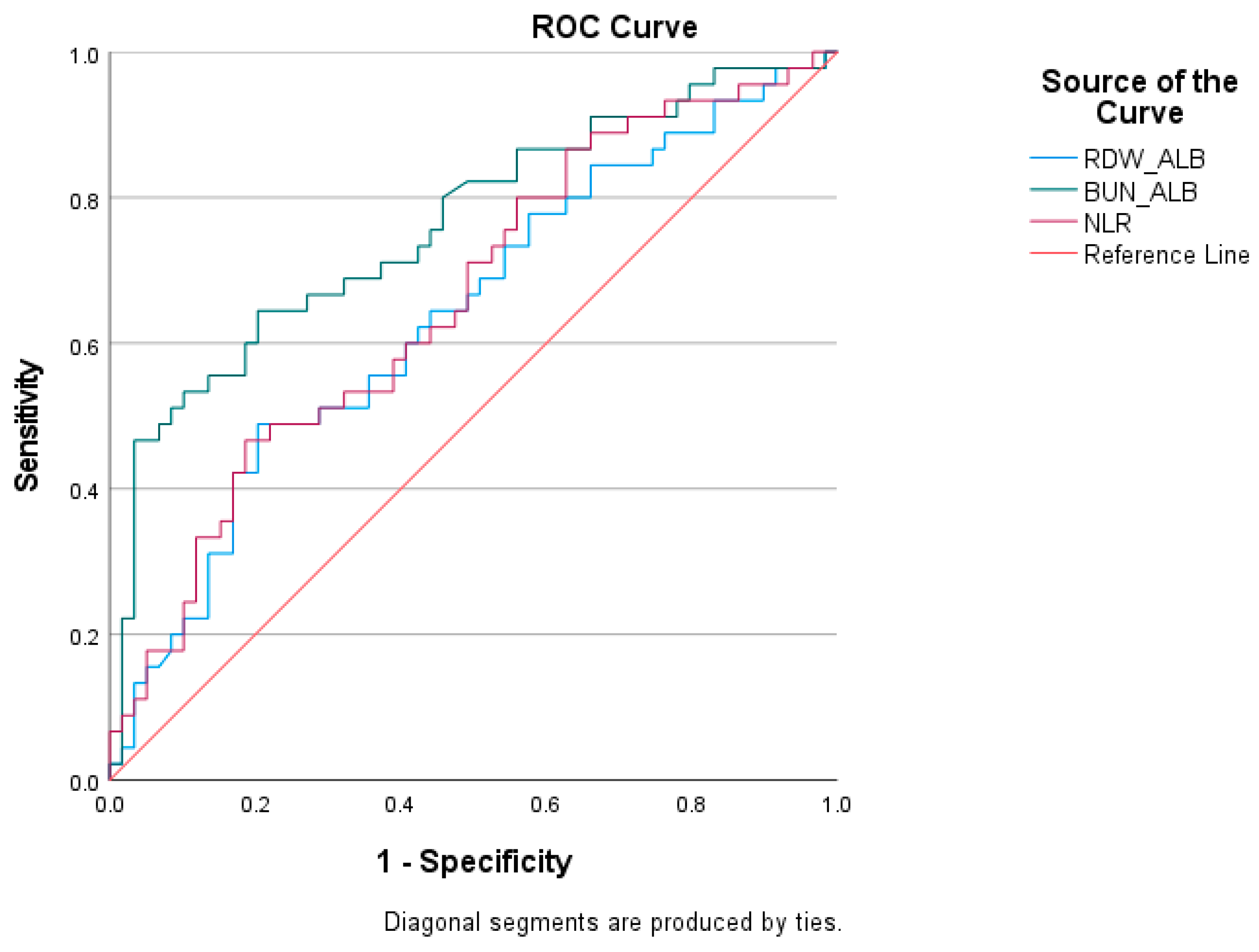

| Test Result Variables | Cutoff | AUC | Std. Error | p | Asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| RDW/ALB | >0.83 | 0.638 | 0.055 | 0.012 | 0.538 | 0.730 | 48.89 | 79.66 |

| BUN/ALB | >1.86 | 0.761 | 0.048 | 0.001 | 0.668 | 0.839 | 64.44 | 79.66 |

| NLR | >13.13 | 0.658 | 0.054 | 0.006 | 0.552 | 0.764 | 62.20 | 51.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kırık, S.; Efgan, M.G.; Bora, E.S.; Kanter, E.; Ermete Güler, E.; Duman Şahan, T. The Prognostic Value of Biomarkers in Patients Diagnosed with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010208

Kırık S, Efgan MG, Bora ES, Kanter E, Ermete Güler E, Duman Şahan T. The Prognostic Value of Biomarkers in Patients Diagnosed with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010208

Chicago/Turabian StyleKırık, Süleyman, Mehmet Göktuğ Efgan, Ejder Saylav Bora, Efe Kanter, Ecem Ermete Güler, and Tutku Duman Şahan. 2026. "The Prognostic Value of Biomarkers in Patients Diagnosed with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010208

APA StyleKırık, S., Efgan, M. G., Bora, E. S., Kanter, E., Ermete Güler, E., & Duman Şahan, T. (2026). The Prognostic Value of Biomarkers in Patients Diagnosed with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010208