Hospitalizations for Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients Aged 75 Years or Older with Chronic Coronary Syndrome for the Whole Life Span

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Data Collection and Event Definition

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Follow-Up

3.3. Predictors of Major Cardiovascular Events. Univariate Analysis

3.4. Predictors of Major Cardiovascular Events. Multivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

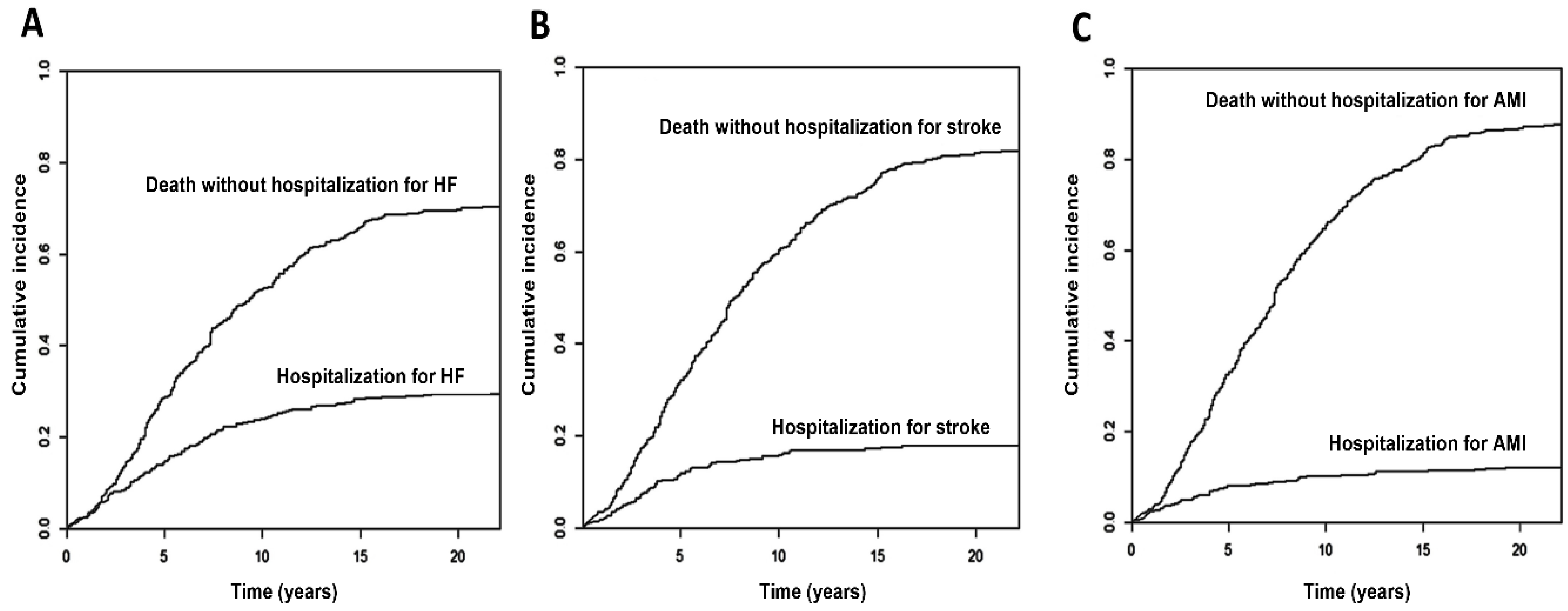

4.1. Lifetime Incidence of Major Cardiovascular Events

4.2. Factors Related to the Incidence of MCE Hospitalization

4.3. Independent Predictors of MCE Hospitalizations

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauters, C.; Deneve, M.; Tricot, O.; Meurice, T.; Lamblin, N.; CORONOR Investigators. Prognosis of patients with stable coronary artery disease (from the CORONOR Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 113, 1142–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W.; D’Agostino, R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Eagle, K.; Pencina, M.J.; Smith, S.C.; Alberts, M.J.; Dallongeville, J.; Goto, S.; Hirsch, A.T.; et al. An international model to predict recurrent cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Med. 2012, 125, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cequier, A.; Bueno, H.; Macaya, C.; Bertomeu, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Íñiguez, A.; Anguita, M.; Cruz, I.; Calvo, D.; Gómez-Doblas, J.J.; et al. Evolución de la asistencia cardiovascular en el Sistema Nacional de Salud de España. Datos del proyecto RECALCAR 2011–2020. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2023, 76, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Ruiz-Ortiz, M.; Ogayar-Luque, C.; Cantón Gálvez, J.M.; Romo Peñas, E.; Mesa Rubio, D.; Delgado Ortega, M.; Castillo Domínguez, J.C.; Anguita Sánchez, M.; López Aguilera, J.; et al. Supervivencia a largo plazo de una población española con cardiopatía isquémica estable: El registro CICCOR. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2019, 72, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Population Projections 2024–2074. Available online: www.ine.es (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Bourgeois, F.; Orenstein, L.; Ballakur, S.; Mandl, K.D.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Exclusion of elderly people from randomized clinical trials of drugs for ischemic heart disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 2354–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, M.; Chyun, D.; Skolnick, A.; Alexander, K.P.; Forman, D.E.; Kitzman, D.W.; Maurer, M.S.; McClurken, J.B.; Resnick, B.M.; Shen, W.K.; et al. Knowledge gaps in cardiovascular care of the older adult population: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Geriatrics Society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 2103–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, M.; Gersh, B.; Alexander, K.; Granger, C.B.; Stone, G.W. Coronary artery disease in patients ≥80 years of age. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2015–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Busby-Whitehead, J.; Forman, D.E.; Alexander, K.P. Stable ischemic heart disease in the older adults. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ortiz, M.; Ogayar, C.; Romo, E.; Mesa, D.; Delgado, M.; Anguita, M.; Castillo, J.C.; Arizón, J.M.; Suárez de Lezo, J. Long-term survival in elderly patients with stable coronary disease. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 43, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ortiz, M.; Romo, E.; Mesa, D.; Delgado, M.; Ogayar, C.; Castillo, J.C.; López Granados, A.; Anguita, M.; Arizón, J.M.; Suárez de Lezo, J. Prognostic value of resting heart rate in a broad population of patients with stable coronary artery disease: Prospective single-center cohort study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2010, 63, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Ortiz, M.; Romo, E.; Mesa, D.; Delgado, M.; Ogayar, C.; Anguita, M.; Castillo, J.C.; Arizón, J.M.; Suárez de Lezo, J. Prognostic impact of baseline low blood pressure in hypertensive patients with stable coronary artery disease of daily clinical practice. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2012, 14, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.; Garcia, M.A.; Ardissino, D.; Buszman, P.; Camici, P.G.; Crea, F.; Daly, C.; De Backer, G.; Hjemdahl, P.; Lopez-Sendon, J.; et al. Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 1341–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.J.; Abrams, J.; Chatterjee, K.; Daley, J.; Deedwania, P.C.; Douglas, J.S.; Ferguson, T.B., Jr.; Fihn, S.D.; Fraker, T.D., Jr.; Gardin, J.M.; et al. American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina. Circulation 2003, 107, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Palomeque, C.; Bardají-Mayor, J.L.; Concha-Ruiz, M.; Cordo Mollar, J.C.; Cosín Aguilar, J.; Magriñá Ballara, J.; Melgares Moreno, R. Guías de práctica clínica de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología en la angina estable. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2000, 53, 967–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassi, A., Jr.; Rassi, A.; Little, W.C.; Xavier, S.S.; Rassi, S.G.; Rassi, A.G.; Rassi, G.G.; Hasslocher-Moreno, A.; Sousa, A.S.; Scanavacca, M.I. Development and validation of a risk score for predicting death in Chagas’ heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbets, E.; Fox, K.M.; Elbez, Y.; Danchin, N.; Dorian, P.; Ferrari, R.; Ford, I.; Greenlaw, N.; Kalra, P.R.; Parma, Z.; et al. CLARIFY investigators Long-term outcomes of chronic coronary syndrome worldwide: Insights from the international CLARIFY registry. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Perez, R.; Otero-Raviña, F.; Franco, M.; Rodríguez Garcia, J.M.; Liñares Stolle, R.; Esteban Alvarez, R.; Iglesias Díaz, C.; Outeiriño López, E.; Vázquez López, M.J.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R. Determinants of cardiovascular mortality in a cohort of primary care patients with chronic ischemic heart disease. BARBANZA Ischemic Heart Disease (BARIHD) study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfisterer, M. Trial of Invasive versus Medical therapy in Elderly patients Investigators. Long-term outcome in elderly patients with chronic angina managed invasively versus by optimized medical therapy. Four-year follow up of the randomized trial of invasive versus medical therapy in elderly patients (TIME). Circulation 2004, 110, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbadi, A.B.; Lemesle, G.; Lamblin, N.; Bauters, C. Very long-term outcomes of older adults with stable coronary artery disease (from the CORONOR study). Coron. Artery Dis. 2022, 33, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Spertus, J.A.; Alexander, K.P.; Newman, J.D.; Dodson, J.A.; Jones, P.G.; Stevens, S.R.; O’Brien, S.M.; Gamma, R.; Perna, G.P. ISCHEMIAResearch Group Health status clinical outcomes in older adults with chronic coronary disease: The ISCHEMIATrial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1697–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parma, Z.; Jasilek, A.; Greenlaw, N.; Ferrari, R.; Ford, I.; Fox, K.; Tardif, J.C.; Tendera, M.; Steg, P.G. Incident heart failure in outpatients with chronic coronary syndrome: Results from the international prospective CLARIFY registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anguita-Sánchez, M.; Bonilla-Palomas, J.L.; García-Márquez, M.; Bernal Sobrino, J.L.; Elola Somoza, F.J.; Marín Ortuño, F. Temporal trends in hospitalization and in-hospital mortality rates due to heart failure by age and sex in Spain (2003–2018). Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; Mosenzon, O.; Kato, E.T.; Cahn, A.; Silverman, M.G.; Zelniker, T.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Bělohlávek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Choi, D.J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Claggett, B.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossello, X.; Mas-Lladó, C.; Pocock, S.; Vicent, L.; van de Werf, F.; Chin, C.T.; Danchin, N.; Lee, S.W.L.; Medina, J.; Huo, Y.; et al. Sex differences in mortality after an acute coronary syndrome increase with lower country wealth and higher income inequality. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2022, 75, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Steg, P.G.; Eagle, K.A.; Goto, S.; Guo, J.; Smith, S.C.; Ohman, E.M.; Scirica, B.M.; REACH Registry Investigators. Angina future cardiovascular events in stable patients with coronary artery disease: Insights from the reduction of atherothrombosis for continued health (REACH) Registry. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, W.E.; O’Rourke, R.A.; Teo, K.K.; Maron, D.J.; Hartigan, P.M.; Sedlis, S.P.; Dada, M.; Labedi, M.; Spertus, J.A.; Kostuk, W.J.; et al. Impact of optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention on long-term cardiovascular end points in patients with stable coronary artery disease (from the COURAGE trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 104, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, E.L.; Samadashvili, Z.; Cozzens, K.; Walford, G.; Jacobs, A.K.; Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Stamato, N.J.; Gold, J.P.; Sharma, S.; Venditti, F.J.; et al. Comparative outcomes for patients who do and do not undergo percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary artery disease in New York. Circulation 2012, 125, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, D.; Hochman, J.; Reynolds, H.; Bangalore, S.; O’Brien, S.M.; Boden, W.E.; Chaitman, B.R.; Senior, R.; López-Sendón, J.; Alexander, K.P.; et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes: Developed by the task force on the management of acute coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826, Erratum in Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibanez, B.; Latini, R.; Rosello, X.; Dominguez-Rodriguez, A.; Fernández-Vazquez, F.; Pelizzoni, V.; Sánchez, P.L.; Anguita, M.; Barrabés, J.A.; Raposeiras-Roubín, S.; et al. Beta-Blockers after Myocardial Infarction without Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 1889–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasan, R.S.; Larson, M.G.; Leip, E.P.; Evans, J.C.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Kannel, W.B.; Levy, D. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camafort, M.; Kasiakogias, A.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Masi, S.; Iliakis, P.; Benetos, A.; Jeong, J.O.; Lee, H.Y.; Muiesan, M.L.; Sudano, I.; et al. Hypertensive heart disease in older patients: Considerations for clinical practice. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 134, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPRINTResearch Group; Wright, J.T., Jr.; Williamson, J.D.; Whelton, P.K.; Snyder, J.K.; Sink, K.M.; Rocco, M.V.; Reboussin, D.M.; Rahman, M.; Oparil, S.; et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2103–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdecchia, P.; Staessen, J.A.; Angeli, F.; de Simone, G.; Achilli, A.; Ganau, A.; Mureddu, G.; Pede, S.; Maggioni, A.P.; Lucci, D.; et al. Usual versus tight control of systolic blood pressure in non-diabetic patients with hypertension (Cardio-Sis): An open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodanno, D.; Petronio, A.S.; Prendergast, B.; Eltchaninoff, H.; Vahanian, A.; Modine, T.; Lancellotti, P.; Sondergaard, L.; Ludman, P.F.; Tamburino, C.; et al. Standardized definitions of structural deterioration and valve failure in assessing long-term durability of transcatheter and surgical aortic bioprosthetic valves: A consensus statement from the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) endorsed by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017, 52, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Figal, D.; Bayés-Genís, A.; Mirabet-Pérez, S.; Cebrián Cuenca, A.M.; de la Hera Galarza, J.; CastroConde, A.; Obaya Rebollar, J.C.; Pallarés-Carratalá, V.; Montanya Mias, E.; Botana López, M.; et al. Documento Clínico de Posicionamiento Para la Detección y la Atención Precoces Del Estrés Cardiaco y la Insuficiencia Cardiaca en Personas Con Diabetes Tipo 2; Sociedad Española de Cardiología: Madrid, Spain, 2024; ISBN 978-84-10072-69-5. Available online: https://secardiologia.es/publicaciones/catalogo/libros/15637-documento-clinico-posicionamiento-deteccion-atencion-precoces-estres-cardiaco-insuficiencia-cardiaca-con-diabetes-tipo-2 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Cerqueiro-González, J.M.; González-Franco, Á.; Carrascosa-García, S.; Soler-Rangel, L.; Ruiz-Laiglesia, F.J.; Epelde-Gonzalo, F.; Dávila-Ramos, M.F.; Casado-Cerrada, J.; Casariego-Vales, E.; Manzano, L. Benefits of a Comprehensive Care Model in Patients with Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction: The UMIPIC Program. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2022, 222, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averbuch, T.; Lee, S.F.; Zagorski, B.; Mebazaa, A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Thabane, L.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Effect of a Transitional Care Model Following Hospitalization for Heart Failure: 3-Year Outcomes of the Patient-Centered Care Transitions in Heart Failure (PACT-HF) Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total N = 414 | Major CV Events N = 198 | No Major CV Events N = 216 | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 79.0 ± 3.7 | 79.0 ± 3.7 | 79.0 ± 3.6 | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.248 |

| Female Sex | 149 (36%) | 82 (41.4%) | 57 (31%) | 1.25 (0.94–1.60) | 0.119 |

| Risk factors | |||||

| Arterial hypertension | 265 (64.3%) | 143 (72.6%) | 122 (56.7%) | 1.62 (1.18–2.22) | 0.003 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 131 (31.8%) | 74 (37.6%) | 57 (26.5%) | 1.46 (1.09–1.95) | 0.011 |

| Dyslipidemia | 268 (72.8%) | 126 (72.8%) | 142 (71.9%) | 0.79 (0.57–1.11) | 0.177 |

| Active smoker | 5 (1.2%) | 2 (1.0%) | 3 (1.4%) | 2.18 (0.30–15.85) | 0.440 |

| Family history | 17 (4.2%) | 10 (5.2%) | 7 (3.3%) | 1.28 (0.68–2.43) | 0.442 |

| Prior disease | |||||

| Previous ACS | 377 (91.3%) | 183 (92.4%) | 194 (90.2%) | 1.37 (0.81–2.33) | 0.237 |

| Angina and ischemia | 22 (5.3%) | 8 (4.0%) | 14 (6.5%) | 0.60 (0.29–1.21) | 0.152 |

| Previous revascularization 1 | 108 (26.2%) | 44 (22.2%) | 64 (29.9%) | 0.78 (0.55–1.08) | 0.139 |

| Percutaneous | 79 (19.1%) | 29 (14.6%) | 50 (23.3%) | 0.66 (0.45–0.98) | 0.040 |

| Surgical | 35 (8.5%) | 17 (8.6%) | 18 (8.3%) | 1.12 (0.68–1.84) | 0.665 |

| Previous stroke | 17 (4.2%) | 9 (4.6%) | 8 (3.8%) | 1.34 (0.68–2.63) | 0.390 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 50 (12.3%) | 30 (15.3%) | 20 (9.5%) | 1.81 (1.23–2.68) | 0.003 |

| Heart failure | 31 (7.5%) | 22 (11.1%) | 9 (4.2%) | 2.86 (1.82–4.50) | <0.0005 |

| Symptoms and physical exam | |||||

| Angor FC ≥ II | 99 (24%) | 49 (24.9%) | 50 (23.1%) | 1.10 (0.79–1.51) | 0.575 |

| Baseline SBP (mmHg) | 130 ± 17 | 131 ± 19 | 130 ± 16 | 1,00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.514 |

| Baseline DBP (mmHg) | 73 ± 10 | 72 ± 10 | 73 ± 9 | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.122 |

| Baseline HR (lpm) | 68 ± 11 | 69 ± 13 | 68 ± 10 | 1,01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.240 |

| Complementary tests | |||||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 117 ± 37 | 120 ± 44 | 114 ± 29 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 1.004 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 193 ± 40 | 194 ± 41 | 192 ± 40 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.447 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 53 ± 14 | 53 ± 15 | 53 ± 13 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.786 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 116 ± 36 | 116 ± 36 | 115 ± 36 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.393 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 126 ± 79 | 127 ± 70 | 124 ± 86 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.480 |

| GFR (mg/min) | 60.2 ± 15.0 | 54.3 ±14.6 | 65.6 ± 13.3 | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | <0.0005 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.4 ± 1.5 | 13.1 ± 1.6 | 13.7 ± 1.3 | 0.82 (0.68–0.99) | 0.039 |

| Leukocytes (103/μL) | 7.7 ± 2.1 | 7.8 ± 2.0 | 7.6 ± 2.1 | 1.12 (0.97–1.29) | 0.124 |

| Platelets (103/μL) | 231.0 ± 76.2 | 236.4 ± 82.3 | 226.2 ± 70.6 | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 0.043 |

| Abnormal ECG | 231 (59.5%) | 121 (64.4%) | 110 (55%) | 1.18 (0.87–1.58) | 0.288 |

| Cardiomegaly | 53 (15.1%) | 32 (19.2%) | 21 (11.5%) | 2.04 (1.38–3.02) | <0.0005 |

| Baseline LVEF (%) | 53.8 ± 14.6 | 54.4 ± 14.6 | 53.3 ± 14.6 | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.960 |

| Baseline treatment | |||||

| Antiplatelet therapy | 353 (85.5%) | 164 (82.8%) | 189 (87.9%) | 0.70 (0.48–1.01) | 0.057 |

| Aspirin | 320 (77.5%) | 151 (76.3%) | 169 (78.6%) | 0.76 (0.54–1.05) | 0.098 |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 46 (11.1%) | 25 (12.6%) | 21 (9.8%) | 1.58 (1.03–2.40) | 0.035 |

| Nitrates | 307 (74.2%) | 153 (77.3%) | 154 (71.3%) | 1.32 (0.94–1.84) | 0.105 |

| ACEI | 207 (50.2%) | 103 (52%) | 104 (48.6%) | 1.08 (0.81–1.42) | 0.609 |

| ARB-II | 50 (12.1%) | 32 (16.2%) | 18 (8.4%) | 1.62 (1.11–2.37) | 0.013 |

| ACEI/ARB-II | 251 (60.9%) | 130 (65.7%) | 121 (56.5%) | 1.33 (0.99–1.79) | 0.056 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 201 (48.6%) | 93 (47%) | 108 (50%) | 0.96 (0.73–1.27) | 0.786 |

| Beta-blockers | 235 (63.2%) | 107 (59.1%) | 128 (67%) | 0.86 (0.64–1.16) | 0.338 |

| Statins | 235 (62.2%) | 105 (58.0%) | 130 (66.0%) | 0.72 (0.54–0.97) | 0.032 |

| Diuretics | 181 (43.8%) | 99 (50.0%) | 82 (38.1%) | 1.77 (1.34–2.35) | <0.0005 |

| Digoxin | 29 (7.0%) | 19 (9.6%) | 10 (4.7%) | 2.20 (1.36–3.56) | 0.001 |

| Variable | Heart Failure Hospitalization N = 122 | No Hospitalization for Heart Failure N = 292 | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial hypertension | 88 (72.7%) | 177 (60.8%) | 1.66 (1.11–2.48) | 0.013 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 49 (40.5%) | 82 (28.2%) | 1.74 (1.21–2.52) | 0.003 |

| Active smoker | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (1.4%) | 4.54 (0.61–33.63) | 0.139 |

| Previous ACS | 115 (94.3%) | 262 (90%) | 1.85 (0.86–3.98) | 0.114 |

| Angina and ischemia | 1 (0.8%) | 21 (7.2%) | 0.11 (0.02–0.80) | 0.029 |

| Previous revascularization 1 | 22 (18%) | 86 (29.7%) | 0.64 (0.40–1.02) | 0.061 |

| Percutaneous | 12 (9.8%) | 67 (23%) | 0.44 (0.24–0.80) | 0.007 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 24 (19.8%) | 26 (9.1%) | 2.62 (1.67–4.11) | <0.0005 |

| Heart failure | 22 (18%) | 9 (3.1%) | 6.42 (3.96–10.40) | <0.0005 |

| Baseline DBP (mmHg) | 70.8 ± 9.8 | 73.6 ± 8.6 | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.002 |

| Baseline HR (lpm) | 69.0 ± 11.8 | 67.8 ± 11.2 | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.102 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 50.0 ± 13.0 | 54.1 ± 14.6 | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.019 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 136.3 ± 79.5 | 121.3 ± 78.0 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.048 |

| GFR (mg/min) | 53.4 ±13.4 | 63.2 ± 14.8 | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) | 0.001 |

| Platelets (103/μL) | 223.1 ± 90.0 | 230.1 ± 70.0 | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.141 |

| Abnormal ECG | 81 (71.7%) | 150 (54.5%) | 1.74 (1.15–2.63) | 0.008 |

| Cardiomegaly | 26 (25.2%) | 27 (10.9%) | 3.27 (2.08–5.16) | <0.0005 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 94 (77.0%) | 259 (89.0%) | 0.47 (0.31–0.72) | <0.0005 |

| Aspirin | 92 (75.4%) | 228 (78.4%) | 0.71 (0.47–1.07) | 0.099 |

| Vitamin K antagonists | 22 (18.0%) | 24 (8.2%) | 2.66 (1.66–4.25) | <0.0005 |

| ACEI | 70 (57.4%) | 137 (47.2%) | 1.42 (0.99–2.04) | 0.056 |

| ARB-II | 24 (19.7%) | 26 (9.0%) | 2.06 (1.32–3.22) | 0.002 |

| ACEI/ARB-II | 92 (75.4%) | 159 (54.8%) | 2.32 (1.53–3.50) | <0.0005 |

| Statins | 57 (51.8%) | 178 (66.4%) | 0.58 (0.40–0.85) | 0.005 |

| Diuretics | 68 (55.7%) | 113 (38.8%) | 2.31 (1.61–3.32) | <0.0005 |

| Digoxin | 17 (14.0%) | 12 (4.1%) | 3.61 (2.15–6.09) | <0.0005 |

| Variable | Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction N = 50 | No Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction N = 364 | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial hypertension | 27 (54%) | 238 (65.7%) | 0.65 (0.37–1.13) | 0.125 |

| Active smoker | 1 (2.0%) | 4 (1.1%) | 5.27 (0.71–39.16) | 0.105 |

| Angor FC ≥ II | 16 (32.0%) | 83 (22.9%) | 1.57 (0.86–2.84) | 0.139 |

| Baseline DBP (mmHg) | 75.3 ± 8.6 | 72.5 ± 9.1 | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 0.094 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 201.4 ± 42.9 | 191.4 ± 39.9 | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.117 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 124.0 ± 36.5 | 114.5 ± 36.1 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.094 |

| ACEI | 20 (40.0%) | 187 (51.7%) | 0.65 (0.37–1.14) | 0.136 |

| ACEI/ARB-II | 23 (46.0%) | 228 (63%) | 0.55 (0.32–0.97) | 0.038 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 31 (62.0%) | 170 (46.7%) | 1.67 (0.94–2.96) | 0.079 |

| Beta-blockers | 25 (52.1%) | 210 (64.8%) | 0.64 (0.37–1.13) | 0.127 |

| Variable | Hospitalization for Stroke N = 74 | No Hospitalization for Stroke N = 340 | Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial hypertension | 58 (78.4%) | 207 (61.2%) | 2.15 (1.24–3.75) | 0.007 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28 (37.8%) | 103 (30.5%) | 1.45 (0.90–2.32) | 0.125 |

| Active smoker | 2 (2.7%) | 3 (0.9%) | 7.00 (1.66–29.47) | 0.008 |

| Previous revascularization 1 | 14 (18.9%) | 94 (27.8%) | 0.65 (0.36–1.16) | 0.141 |

| Previous stroke | 5 (6.8%) | 12 (3.6%) | 2.11 (0.84–5.26) | 0.110 |

| Baseline SBP (mmHg) | 134.7 ± 18.2 | 129.2 ± 16.9 | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.013 |

| GFR (mg/min) | 55.9 ± 13.0 | 61.2 ± 15.3 | 0.97 (0.94–1.01) | 0.096 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barreiro Mesa, L.; Ruiz Ortiz, M.; López Baizán, J.; Mateos de la Haba, L.; Ogayar Luque, C.; Sánchez Fernández, J.J.; Romo Peñas, E.; Delgado Ortega, M.; Rodríguez Almodóvar, A.; Esteban Martínez, F.; et al. Hospitalizations for Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients Aged 75 Years or Older with Chronic Coronary Syndrome for the Whole Life Span. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010207

Barreiro Mesa L, Ruiz Ortiz M, López Baizán J, Mateos de la Haba L, Ogayar Luque C, Sánchez Fernández JJ, Romo Peñas E, Delgado Ortega M, Rodríguez Almodóvar A, Esteban Martínez F, et al. Hospitalizations for Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients Aged 75 Years or Older with Chronic Coronary Syndrome for the Whole Life Span. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):207. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010207

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarreiro Mesa, Lucas, Martín Ruiz Ortiz, Josué López Baizán, Leticia Mateos de la Haba, Cristina Ogayar Luque, José Javier Sánchez Fernández, Elías Romo Peñas, Mónica Delgado Ortega, Ana Rodríguez Almodóvar, Fátima Esteban Martínez, and et al. 2026. "Hospitalizations for Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients Aged 75 Years or Older with Chronic Coronary Syndrome for the Whole Life Span" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010207

APA StyleBarreiro Mesa, L., Ruiz Ortiz, M., López Baizán, J., Mateos de la Haba, L., Ogayar Luque, C., Sánchez Fernández, J. J., Romo Peñas, E., Delgado Ortega, M., Rodríguez Almodóvar, A., Esteban Martínez, F., Anguita Sánchez, M., González Manzanares, R., Castillo Domínguez, J. C., López Aguilera, J., López Granados, A., Pan Álvarez-Ossorio, M., & Mesa Rubio, D. (2026). Hospitalizations for Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients Aged 75 Years or Older with Chronic Coronary Syndrome for the Whole Life Span. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010207