Association Between ECG Findings on Presentation and Outcomes in Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Laboratory Parameters

2.3. Echocardiography

2.4. Electrocardiographic Data

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Future Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Templin, C.; Ghadri, J.R.; Diekmann, J.; Napp, L.C.; Bataiosu, D.R.; Jaguszewski, M.; Cammann, V.L.; Sarcon, A.; Geyer, V.; Neumann, C.A.; et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Takotsubo (Stress) Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citro, R.; Lyon, A.R.; Meimoun, P.; Omerovic, E.; Redfors, B.; Buck, T.; Lerakis, S.; Parodi, G.; Silverio, A.; Eitel, I.; et al. Standard and advanced echocardiography in takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy: Clinical and prognostic implications. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina de Chazal, H.; Del Buono, M.G.; Keyser-Marcus, L.; Ma, L.; Moeller, F.G.; Berrocal, D.; Abbate, A. Stress Cardiomyopathy Diagnosis and Treatment: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1955–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.; Lerman, A.; Rihal, C.S. Apical ballooning syndrome (Tako-Tsubo or stress cardiomyopathy): A mimic of acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 2008, 155, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadri, J.-R.; Wittstein, I.S.; Prasad, A.; Sharkey, S.; Dote, K.; Akashi, Y.J.; Cammann, V.L.; Crea, F.; Galiuto, L.; Desmet, W.; et al. International Expert Consensus Document on Takotsubo Syndrome (Part I): Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Criteria, and Pathophysiology. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 2032–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almendro-Delia, M.; López-Flores, L.; Uribarri, A.; Vedia, O.; Blanco-Ponce, E.; López-Flores, M.D.C.; Rivas-García, A.P.; Fernández-Cordón, C.; Sionis, A.; Martín-García, A.C.; et al. Recovery of Left Ventricular Function and Long-Term Outcomes in Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, R.T.; Prasad, A.; Askew, J.W., 3rd; Sengupta, P.P.; Tajik, A.J. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: A unique cardiomyopathy with variable ventricular morphology. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2010, 3, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, C.; Paduraru, L.; Balanescu, S. An Extensive Review on Imaging Diagnosis Methods in Takotsubo Syndrome. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citro, R.; Okura, H.; Ghadri, J.R.; Izumi, C.; Meimoun, P.; Izumo, M.; Dawson, D.; Kaji, S.; Eitel, I.; Kagiyama, N.; et al. Multimodality imaging in takotsubo syndrome: A joint consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) and the Japanese Society of Echocardiography (JSE). J. Echocardiogr. 2020, 18, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alashi, A.; Isaza, N.; Faulx, J.; Popovic, Z.B.; Menon, V.; Ellis, S.G.; Faulx, M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Griffin, B.P.; Desai, M.Y. Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome: Incremental Prognostic Value of Baseline Left Ventricular Systolic Function. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citro, R.; Radano, I.; Parodi, G.; Di Vece, D.; Zito, C.; Novo, G.; Provenza, G.; Bellino, M.; Prota, C.; Silverio, A.; et al. Long-term outcome in patients with Takotsubo syndrome presenting with severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, T.; Khan, H.; Gamble, D.T.; Scally, C.; Newby, D.E.; Dawson, D. Takotsubo Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Emerging Concepts, and Clinical Implications. Circulation 2022, 145, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isogai, T.; Matsui, H.; Tanaka, H.; Makito, K.; Fushimi, K.; Yasunaga, H. Incidence, management, and prognostic impact of arrhythmias in patients with Takotsubo syndrome: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2023, 12, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, S.; Richter, J.; Pappalardo, F.; Bělohlávek, J.; Lorusso, R.; Schmitto, J.D.; Bauersachs, J.; Napp, L.C. Mechanical circulatory support for Takotsubo syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 316, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.A.; Madhavan, M.; Prasad, A. Brain natriuretic peptide in apical ballooning syndrome (Takotsubo/stress cardiomyopathy): Comparison with acute myocardial infarction. Coron. Artery Dis. 2012, 23, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, M.S.; Dhillon, A.S.; Taylor, H.C.; Sun, Z.; Desai, M.Y. Diagnostic utility of cardiac biomarkers in discriminating Takotsubo cardiomyopathy from acute myocardial infarction. J. Card. Fail. 2014, 20, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, M.; Borlaug, B.A.; Lerman, A.; Rihal, C.S.; Prasad, A. Stress hormone and circulating biomarker profile of apical ballooning syndrome (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy): Insights into the clinical significance of B-type natriuretic peptide and troponin levels. Heart 2009, 95, 1436–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, F.; Kaski, J.C.; Crea, F.; Camici, P.G. Pathophysiology of Takotsubo Syndrome. Circulation 2017, 135, 2426–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangieh, A.H.; Obeid, S.; Ghadri, J.; Imori, Y.; D’AScenzo, F.; Kovac, M.; Ruschitzka, F.; Lüscher, T.F.; Duru, F.; Templin, C.; et al. ECG Criteria to Differentiate Between Takotsubo (Stress) Cardiomyopathy and Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, R.; Hiasa, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Fujiwara, K.; Ohara, Y.; Nada, T.; Ogata, T.; Kusunoki, K.; Yuba, K.; et al. Specific findings of the standard 12-lead ECG in patients with ‘Takotsubo’ cardiomyopathy: Comparison with the findings of acute anterior myocardial infarction. Circ. J. 2003, 67, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, L.; Butt, N.; Ahmad, S.A.; Kayani, W.T.; Sangong, A.; Patel, V.; Bharaj, G.; Khalid, N. Electrocardiographic changes in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. J. Electrocardiol. 2021, 65, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namgung, J. Electrocardiographic Findings in Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy: ECG Evolution and Its Difference from the ECG of Acute Coronary Syndrome. Clin. Med. Insights Cardiol. 2014, 8, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moady, G.; Rubinstein, G.; Mobarki, L.; Atar, S. Takotsubo Syndrome in the Emergency Room—Diagnostic Challenges and Suggested Algorithm. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsuma, W.; Kodama, M.; Ito, M.; Tanaka, K.; Yanagawa, T.; Ikarashi, N.; Sugiura, K.; Kimura, S.; Yagihara, N.; Kashimura, T.; et al. Serial electrocardiographic findings in women with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 100, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeijlon, R.; Jha, S.; Le, V.; Chamat, J.; Espinosa, A.S.; Poller, A.; Thorleifsson, S.; Bobbio, E.; Mellberg, T.; Pirazzi, C.; et al. Temporal electrocardiographic changes in anterior ST elevation myocardial infarction versus the Takotsubo syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2023, 45, 101187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, J.L.; Wong, C.W.; Lee, M.; Khan, A.; Webster, M.; Kerr, A.J. Usefulness of ECG to differentiate Takotsubo cardiomyopathy from acute coronary syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 199, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nable, J.V.; Brady, W. The evolution of electrocardiographic changes in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2009, 27, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Buono, M.G.; Damonte, J.I.; Moroni, F.; Ravindra, K.; Westman, P.; Chiabrando, J.G.; Bressi, E.; Li, P.; Kapoor, K.; Mao, Y.; et al. QT Prolongation and In-Hospital Ventricular Arrhythmic Complications in Patients with Apical Ballooning Takotsubo Syndrome. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2022, 8, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, E.R.; Mahida, S. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and the long-QT syndrome: An insult to repolarization reserve. Europace 2009, 11, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, T.F.; Rahman, I.; Dikdan, S.; Shah, R.; Niazi, O.T.; Thirunahari, N.; Alhaj, E.; Klapholz, M.; Gaziano, J.M.; Djousse, L. QT Prolongation and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2016, 39, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadri, J.R.; Cammann, V.L.; Napp, L.C.; Jurisic, S.; Diekmann, J.; Bataiosu, D.R.; Seifert, B.; Jaguszewski, M.; Sarcon, A.; Neumann, C.A.; et al. Differences in the Clinical Profile and Outcomes of Typical and Atypical Takotsubo Syndrome: Data from the International Takotsubo Registry. JAMA Cardiol. 2016, 1, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, F.; Stiermaier, T.; Tarantino, N.; Guastafierro, F.; Graf, T.; Möller, C.; Di Martino, L.F.; Thiele, H.; Di Biase, M.; Eitel, I.; et al. Impact of persistent ST elevation on outcome in patients with Takotsubo syndrome. Results from the GErman Italian STress Cardiomyopathy (GEIST) registry. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 255, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gietzen, T.; El-Battrawy, I.; Lang, S.; Zhou, X.; Ansari, U.; Behnes, M.; Borggrefe, M.; Akin, I. Impact of T-inversion on the outcome of Takotsubo syndrome as compared to acute coronary syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 49, e13078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, S.; Zeijlon, R.; Enabtawi, I.; Espinosa, A.S.; Chamat, J.; Omerovic, E.; Redfors, B. Electrocardiographic predictors of adverse in-hospital outcomes in the Takotsubo syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 299, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xenogiannis, I.; Vemmou, E.; Nikolakopoulos, I.; Nowariak, M.E.; Schmidt, C.W.; Brilakis, E.S.; Sharkey, S.W. The impact of ST-segment elevation on the prognosis of patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. J. Electrocardiol. 2022, 75, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, M.; Kato, K.; Kondo, Y.; Kitahara, H.; Kobayashi, Y. Temporal repolarization abnormality and ventricular arrhythmic risk in takotsubo syndrome. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, ehaf784.2771. [Google Scholar]

- Nef, H.M.; Möllmann, H.; Kostin, S.; Troidl, C.; Voss, S.; Weber, M.; Dill, T.; Rolf, A.; Brandt, R.; Hamm, C.W.; et al. Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy: Intraindividual structural analysis in the acute phase and after functional recovery. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 2456–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadri, J.R.; Cammann, V.L.; Jurisic, S.; Seifert, B.; Napp, L.C.; Diekmann, J.; Bataiosu, D.R.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Ding, K.J.; Sarcon, A.; et al. A novel clinical score (InterTAK Diagnostic Score) to differentiate takotsubo syndrome from acute coronary syndrome: Results from the International Takotsubo Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, Y.-K.; Kubokawa, S.-I.; Imai, R.-I.; Nakaoka, Y.; Nishida, K.; Seki, S.-I.; Kubo, T.; Yamasaki, N.; Kitaoka, H.; Kawai, K.; et al. Takotsubo Syndrome in Octogenarians and Nonagenarians. Circ. Rep. 2021, 3, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Gad, M.M.; Faulx, M.; Alvarez, P.; Xu, B. Age-related variations in hospital events and outcomes in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: A nationwide cohort study. J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 23, e24–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redfors, B.; Jha, S.; Thorleifsson, S.; Jernberg, T.; Angerås, O.; Frobert, O.; Petursson, P.; Tornvall, P.; Sarno, G.; Ekenbäck, C.; et al. Short- and Long-Term Clinical Outcomes for Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome and Patients with Myocardial Infarction: A Report from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e017290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, J.H.; Bang, L.E.; Rørth, R.; Schou, M.; Kristensen, S.L.; Yafasova, A.; Havers-Borgersen, E.; Vinding, N.E.; Jessen, N.; Kragholm, K.; et al. Long-term Risk of Death and Hospitalization in Patients with Heart Failure and Takotsubo Syndrome: Insights from a Nationwide Cohort. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 28, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Battrawy, I.; Santoro, F.; Núñez-Gil, I.J.; Pätz, T.; Arcari, L.; Abumayyaleh, M.; Guerra, F.; Novo, G.; Musumeci, B.; Cacciotti, L.; et al. Age-Related Differences in Takotsubo Syndrome: Results from the Multicenter GEIST Registry. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e030623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | 119 |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 70 ± 12 |

| Female (n, %) | 112 (94) |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 71 (60) |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 37 (31) |

| Hyperlipidemia (n, %) | 61 (51) |

| Tobacco use (n, %) | 21 (18) |

| Chronic kidney disease (n, %) | 40 (34) |

| Ischemic heart disease (n, %) | 22 (18) |

| Neurological disease (n, %) | 10 (8) |

| Psychiatric disease (n, %) | 15 (13) |

| Presenting symptom | |

| Chest pain (n, %) | 76 (64) |

| Dyspnea (n, %) | 30 (25) |

| Other (n, %) | 13 (11) |

| Trigger (n, %) | 88 (74) |

| n | 119 |

|---|---|

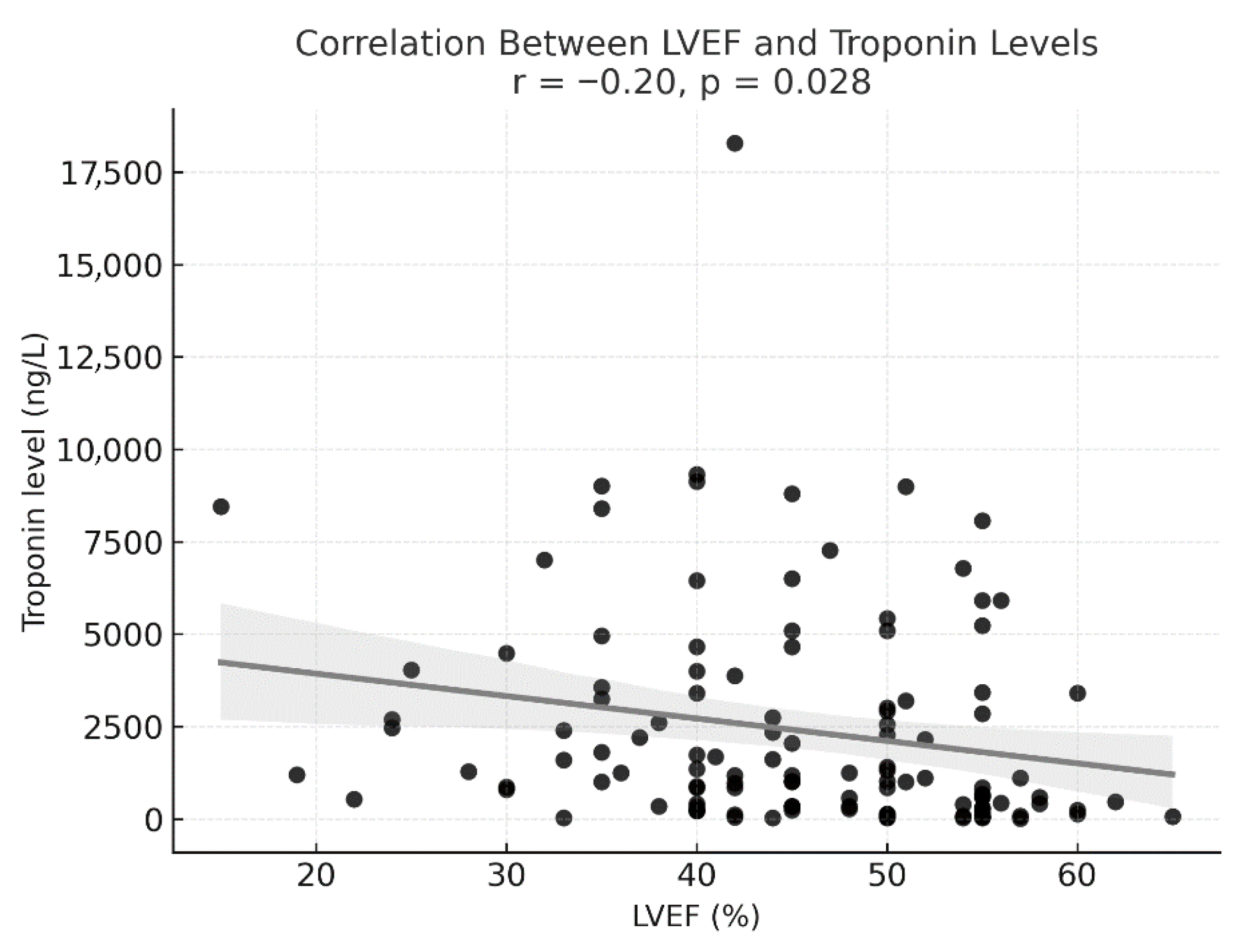

| LVEF % (mean ± SD) | 45 ± 10 |

| ECG changes (n, %) | 59 (50) |

| Time, hours: symptom onset to ECG (median, IQR) | 4.5 (2–5.5) |

| Troponin, ng/L (median, IQR) | 1186 (340–3400) |

| CRP, mg/L (median, IQR) | 15 (5–33) |

| Systolic BP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 123 ± 23 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 73 ± 14 |

| Heart rate, BPM (mean ± SD) | 83 ± 16 |

| WBCs, ×103/μL(mean ± SD) | 10 ± 4 |

| Hemoglobin, gr/dL (mean ± SD) | 12 ± 2 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 0.97 ± 0.4 |

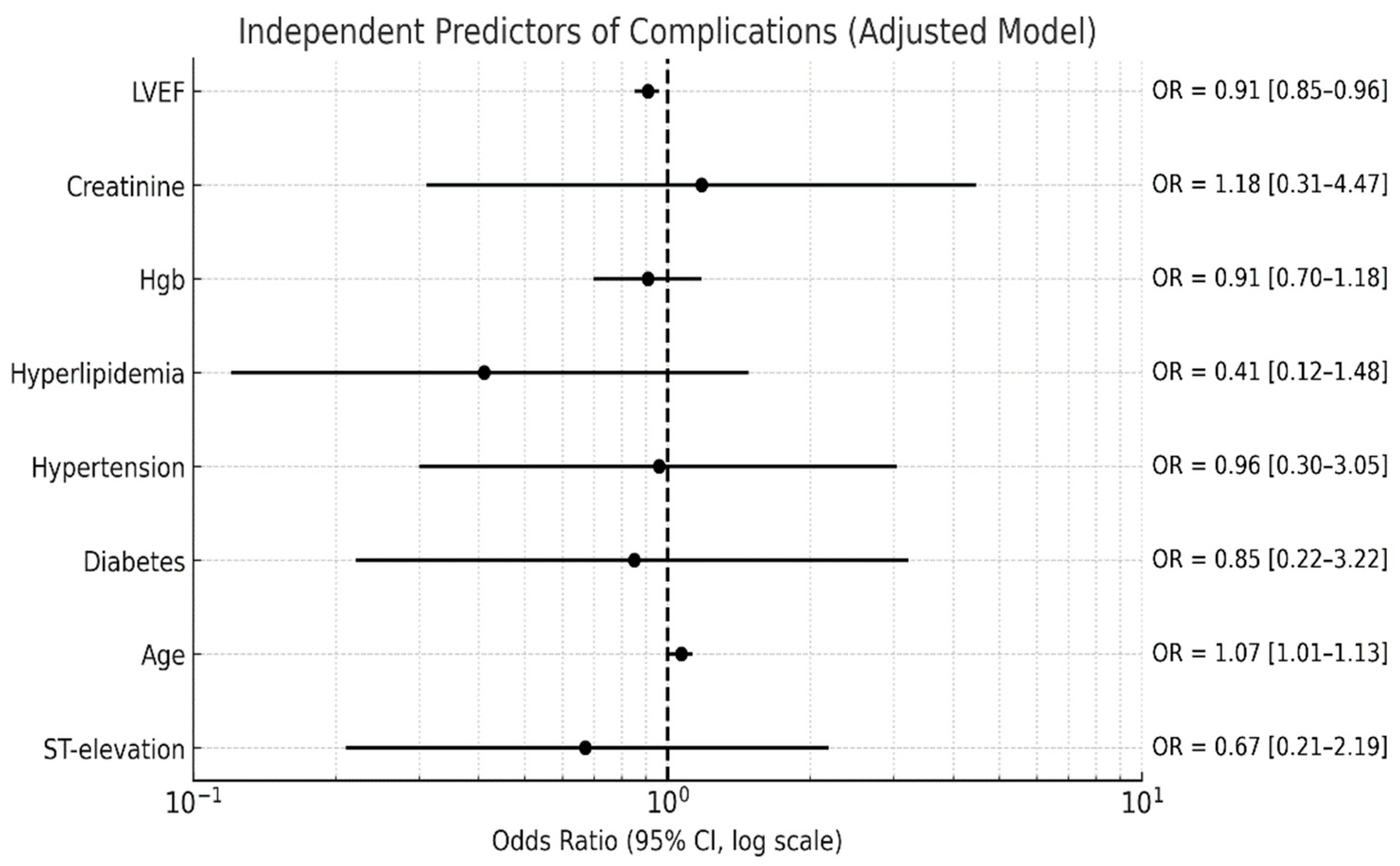

| Complications, HF and arrhythmia (n, %) | 21 (18) |

| Dynamic LVOT obstruction (n, %) | 12 (10) |

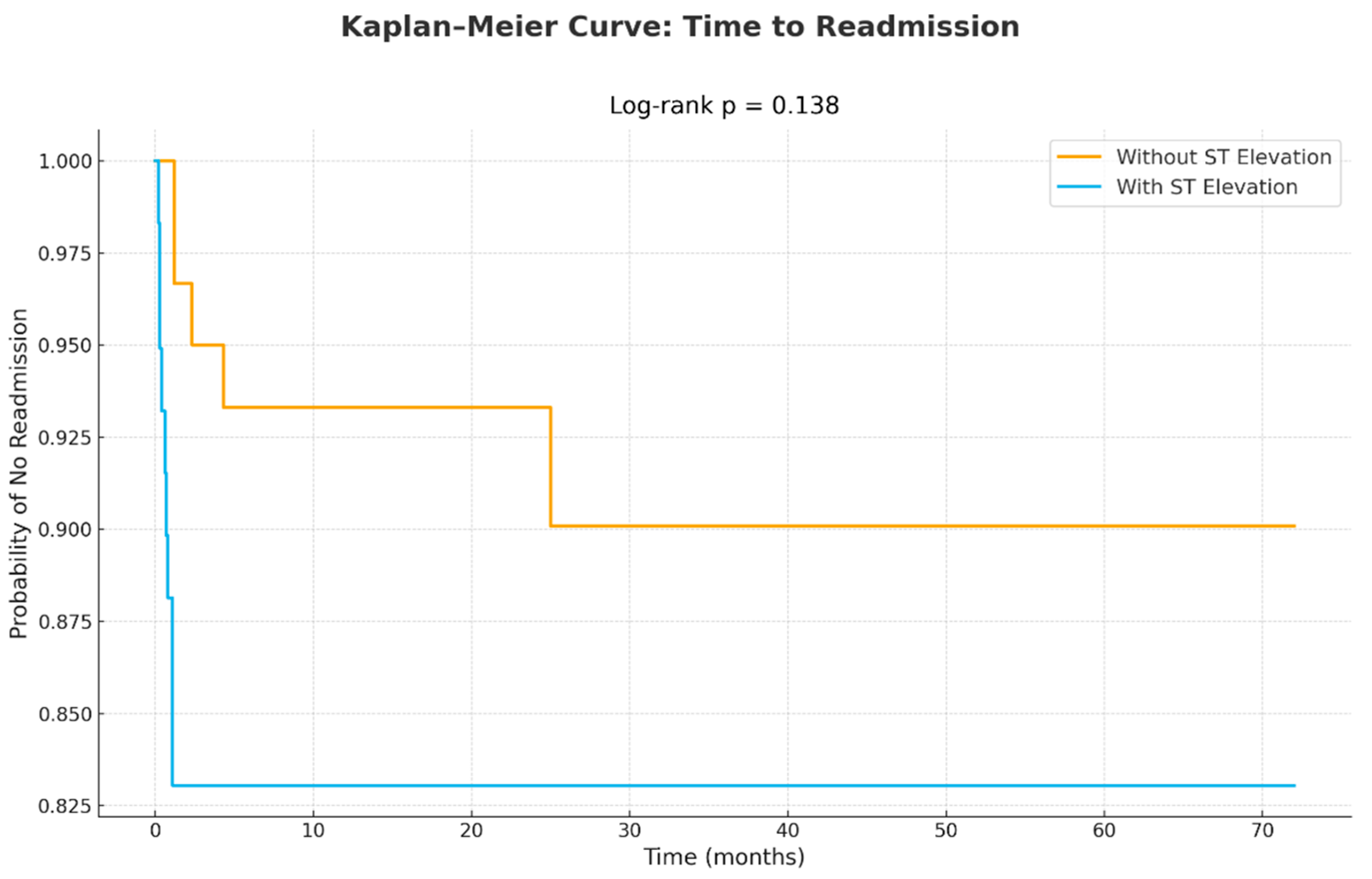

| 1-year total readmissions | 15 (13) |

| Mortality (n, %) | 1 (1) |

| n | With ST Elevation 59 | Without ST Elevation 60 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 71 ± 12 | 69 ± 12 | 0.37 |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 36 (61) | 36 (60) | 1.0 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 20 (34) | 17 (28) | 0.65 |

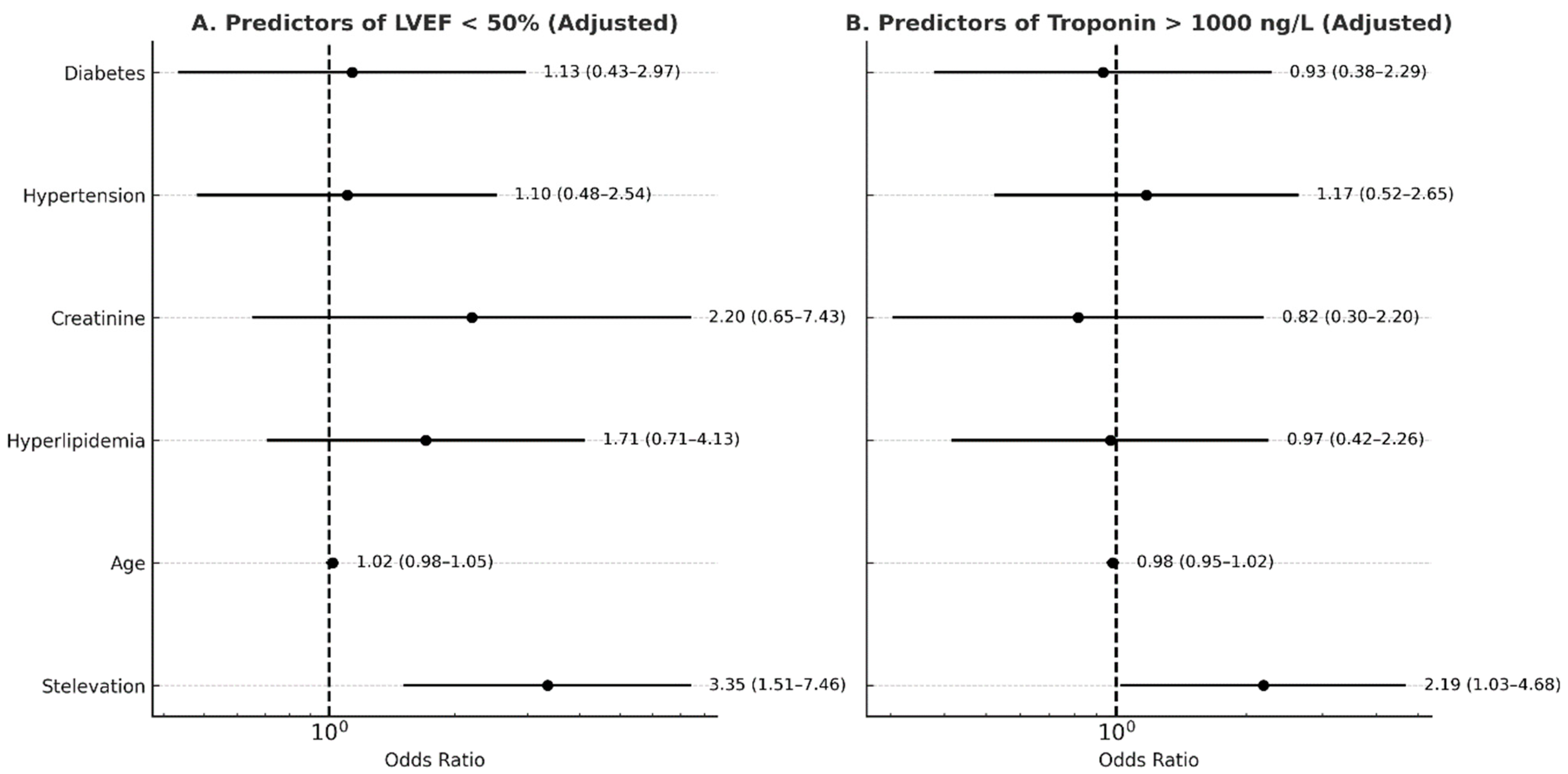

| LVEF % (mean ± SD) | 42 ± 10 | 48 ± 8 | 0.003 * |

| WBCs (×103/μL) | 10.3 ± 4.7 | 10 ± 4.6 | 0.77 |

| Hemoglobin, gr/dL (mean ± SD) | 11.5 ± 2.3 | 11.9 ± 2.2 | 0.34 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 1 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.33 |

| Troponin, ng/L (median, IQR) | 2045 (574–4263) | 911 (226–2403) | 0.014 * |

| CRP, mg/L (mean ± SD) | 14 (5–32) | 15 (7–27) | 0.44 |

| Complications, HF and arrhythmia (n, %) | 16 (27) | 5 (8) | 0.01 * |

| Dynamic LVOT (n, %) | 8 (14) | 4 (7) | 0.21 |

| Total readmissions | 10 (17) | 5 (8) | 0.138 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Levi-Gofman, L.; Atar, S.; Grosbard, D.; Moady, G. Association Between ECG Findings on Presentation and Outcomes in Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010193

Levi-Gofman L, Atar S, Grosbard D, Moady G. Association Between ECG Findings on Presentation and Outcomes in Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010193

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevi-Gofman, Lihi, Shaul Atar, Dana Grosbard, and Gassan Moady. 2026. "Association Between ECG Findings on Presentation and Outcomes in Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010193

APA StyleLevi-Gofman, L., Atar, S., Grosbard, D., & Moady, G. (2026). Association Between ECG Findings on Presentation and Outcomes in Patients with Takotsubo Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010193