The Role of Quantitative Indocyanine Green Angiography with Relative Perfusion Ratio in the Assessment of Gastric Conduit Perfusion in Oesophagectomy: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Surgical Techniques

2.2.1. Ivor Lewis Oesophagectomy

2.2.2. McKeown Oesophagectomy

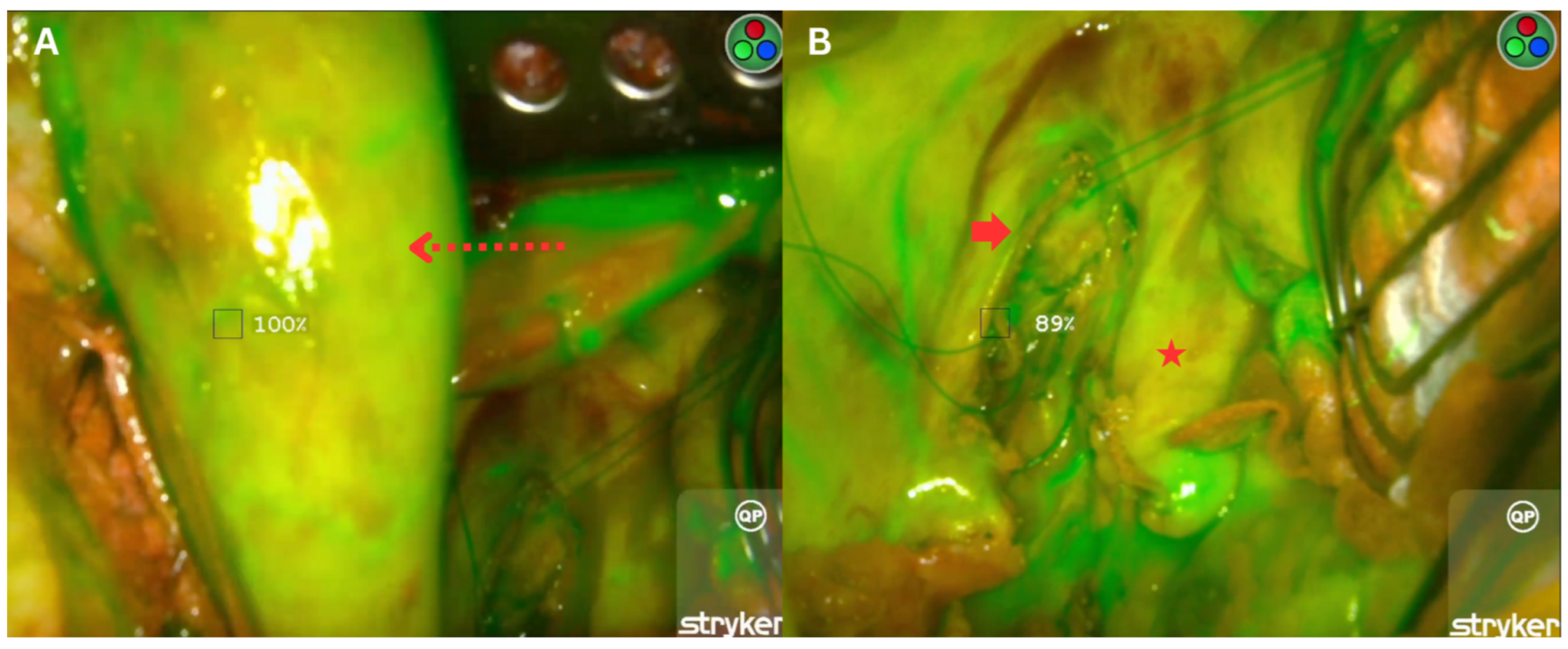

2.3. Fluorescence Imaging with Indocyanine Green

2.4. Postoperative Follow-Up

2.5. Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AL | Anastomotic leak |

| ICG | Indocyanine green |

| RPR | Relative perfusion ratio |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| POR | Point of reference |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| FDA | Food and drug administration |

| CROSS | Chemotherapy for Oesophageal Cancer followed by Surgery Study |

| FLOT | Fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel |

References

- Xiang, Z.-F.; Xiong, H.-C.; Hu, D.-F.; Li, M.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Mao, Z.-C.; Shen, E.-D. Age-Related Sex Disparities in Esophageal Cancer Survival: A Population-Based Study in the United States. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 836914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, D.E.; Kuppusamy, M.K.; Alderson, D.; Cecconello, I.; Chang, A.C.; Darling, G.; Davies, A.; D’journo, X.B.; Gisbertz, S.S.; Griffin, S.M.; et al. Benchmarking Complications Associated with Esophagectomy. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramesh, M.; Shirkhoda, M.; Hadji, M.; Seifi, P.; Omranipour, R.; Mohagheghi, M.A.; Aghili, M.; Jalaeefar, A.; Yousefi, N.K.; Zendedel, K. Esophagectomy complications and mortality in esophageal cancer patients, a comparison between trans-thoracic and trans-hiatal methods. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2018, 16, em127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, G.G.; Mathew, G.; Ludemann, R.; Wayman, J.; Myers, J.C.; Devitt, P.G. Postoperative mortality following oesophagectomy and problems in reporting its rate. Br. J. Surg. 2004, 91, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, N.; Smith, R.C.; Currow, D.C. Survival, mortality and morbidity outcomes after oesophagogastric cancer surgery in New South Wales, 2001–2008. Med. J. Aust. 2014, 201, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiolfi, A.; Sozzi, A.; Bonitta, G.; Lombardo, F.; Cavalli, M.; Cirri, S.; Campanelli, G.; Danelli, P.; Bona, D. Linear- versus circular-stapled esophagogastric anastomosis during esophagectomy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2022, 407, 3297–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goense, L.; Meziani, J.; Ruurda, J.P.; van Hillegersberg, R. Impact of postoperative complications on outcomes after oesophagectomy for cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2019, 106, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markar, S.; Gronnier, C.; Duhamel, A.; Mabrut, J.-Y.; Bail, J.-P.; Carrere, N.; Lefevre, J.H.; Brigand, C.; Vaillant, J.-C.; Adham, M.; et al. The Impact of Severe Anastomotic Leak on Long-term Survival and Cancer Recurrence After Surgical Resection for Esophageal Malignancy. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiolfi, A.; Griffiths, E.A.; Sozzi, A.; Manara, M.; Bonitta, G.; Bonavina, L.; Bona, D. Effect of Anastomotic Leak on Long-Term Survival After Esophagectomy: Multivariate Meta-analysis and Restricted Mean Survival Times Examination. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 5564–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Niimi, M.; Kan, S.; Shatari, T.; Takami, H.; Kodaira, S. Clinical significance of tissue blood flow during esophagectomy by laser Doppler flowmetry. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2001, 122, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.H.; Perry, K.A.; Enestvedt, C.K.; Gareau, D.; Dolan, J.P.; Sheppard, B.C.; Jacques, S.L.; Hunter, J.G. Decreased Conduit Perfusion Measured by Spectroscopy Is Associated With Anastomotic Complications. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011, 91, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pather, K.; Deladisma, A.M.; Guerrier, C.; Kriley, I.R.; Awad, Z.T. Indocyanine green perfusion assessment of the gastric conduit in minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampinis, I.; Ronellenfitsch, U.; Mertens, C.; Gerken, A.; Hetjens, S.; Post, S.; Kienle, P.; Nowak, K. Indocyanine green tissue angiography affects anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy. A retrospective, case-control study. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 48, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.H.; Worrell, S.G. Indocyanine Green Use During Esophagectomy. Surg. Oncol. Clin. 2022, 31, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawa, D.; Hünerbein, M.; Spychała, A.; Nowaczyk, P.; Połom, K.; Murawa, P. Indocyanine green angiography for evaluation of gastric conduit perfusion during esophagectomy-first experience. Acta Chir. Belg. 2012, 112, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, K.C.; Barnes, K.E.; Wile, R.K.; Hung, Y.-Y.; Santos, J.; Hsu, D.S.; Choe, G.; Elmadhun, N.Y.; Ashiku, S.K.; Patel, A.R.; et al. Outcomes of Anastomotic Evaluation Using Indocyanine Green Fluorescence during Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy. Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 5124–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennig, S.; Jansen-Winkeln, B.; Köhler, H.; Knospe, L.; Chalopin, C.; Maktabi, M.; Pfahl, A.; Hoffmann, J.; Kwast, S.; Gockel, I.; et al. Novel Intraoperative Imaging of Gastric Tube Perfusion during Oncologic Esophagectomy-A Pilot Study Comparing Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) and Fluorescence Imaging (FI) with Indocyanine Green (ICG). Cancers 2021, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, G.; Takahashi, C.; Huston, J.; Shridhar, R.; Meredith, K. The use of indocyanine green (ICYG) angiography intraoperatively to evaluate gastric conduit perfusion during esophagectomy: Does it impact surgical decision-making? Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 8720–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozzi, A.; Bona, D.; Yeow, M.; Habeeb, T.A.A.M.; Bonitta, G.; Manara, M.; Sangiorgio, G.; Biondi, A.; Bonavina, L.; Aiolfi, A. Does Indocyanine Green Utilization during Esophagectomy Prevent Anastomotic Leaks? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, M.A.; Angeramo, C.A.; Bras Harriott, C.; Dreifuss, N.H.; Schlottmann, F. Indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging for prevention of anastomotic leak in totally minimally invasive Ivor Lewis esophagectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis. Esophagus 2022, 35, doab056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehetner, J.; DeMeester, S.R.; Alicuben, E.T.; Oh, D.S.; Lipham, J.C.; Hagen, J.A.; DeMeester, T.R. Intraoperative Assessment of Perfusion of the Gastric Graft and Correlation With Anastomotic Leaks After Esophagectomy. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lütken, C.D.; Achiam, M.P.; Osterkamp, J.; Svendsen, M.B.; Nerup, N. Quantification of fluorescence angiography: Toward a reliable intraoperative assessment of tissue perfusion—A narrative review. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, E.; Bredgaard, R.; Bonde, C.; Jensen, L.T.; Damsgaard, T.E. An observational study comparing the SPY-Elite® vs. the SPY-PHI QP system in breast reconstructive surgery. Ann. Breast Surg. 2022, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, I. The surgical treatment of carcinoma of the oesophagus; with special reference to a new operation for growths of the middle third. Br. J. Surg. 1946, 34, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, K.C. Total three-stage oesophagectomy for cancer of the oesophagus. Br. J. Surg. 1976, 63, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.-A. Classification of Surgical Complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcu, E.P.; Salis, A.; Gavini, E.; Rassu, G.; Maestri, M.; Giunchedi, P. Indocyanine green delivery systems for tumour detection and treatments. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 768–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mytych, W.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Aebisher, D. The Medical Basis for the Photoluminescence of Indocyanine Green. Molecules 2025, 30, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.Y.; Mohan, S.; Balasubramaniam, S.; Ahmed, S.; Siew, C.C.H.; Shelat, V.G. Indocyanine green dye and its application in gastrointestinal surgery: The future is bright green. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 1841–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanavičius, L.; Pattyn, P.; Van de Putte, D.; Venskutonis, D. How to assess intestinal viability during surgery: A review of techniques. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2011, 3, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Reames, M.K.; Robinson, M.; Symanowski, J.; Salo, J.C. Conduit Vascular Evaluation is Associated with Reduction in Anastomotic Leak After Esophagectomy. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2015, 19, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransvea, P.; Chiarello, M.M.; Fico, V.; Cariati, M.; Brisinda, G. Indocyanine green: The guide to safer and more effective surgery. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2024, 16, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; Sato, K.; Ozaki, A.; Tomohiro, A.; Sato, T.; Hirano, Y.; Fujiwara, H.; Yoda, Y.; Kojima, T.; Yano, T.; et al. A novel imaging technology to assess oxygen saturation of the gastric conduit in thoracic esophagectomy. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 7597–7606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kroge, P.; Russ, D.; Wagner, J.; Grotelüschen, R.; Reeh, M.; Izbicki, J.R.; Mann, O.; Wipper, S.H.; Duprée, A. Quantification of gastric tube perfusion following esophagectomy using fluorescence imaging with indocyanine green. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2022, 407, 2693–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, N.P.; Joosten, J.J.; Dalli, J.; Hompes, R.; Cahill, R.A.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.I. Evaluation of inter-user variability in indocyanine green fluorescence angiography to assess gastric conduit perfusion in esophageal cancer surgery. Dis. Esophagus 2022, 35, doac016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Hoven, P.; Osterkamp, J.; Nerup, N.; Svendsen, M.B.S.; Vahrmeijer, A.; Van Der Vorst, J.R.; Achiam, M.P. Quantitative perfusion assessment using indocyanine green during surgery—Current applications and recommendations for future use. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalli, J.; Hardy, N.; Mac Aonghusa, P.G.; Epperlein, J.P.; Cantillon Murphy, P.; Cahill, R.A. Challenges in the interpretation of colorectal indocyanine green fluorescence angiography—A video vignette. Color. Dis. 2021, 23, 1289–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishige, F.; Nabeya, Y.; Hoshino, I.; Takayama, W.; Chiba, S.; Arimitsu, H.; Iwatate, Y.; Yanagibashi, H. Quantitative Assessment of the Blood Perfusion of the Gastric Conduit by Indocyanine Green Imaging. J. Surg. Res. 2019, 234, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slooter, M.D.; de Bruin, D.M.; Eshuis, W.J.; Veelo, D.P.; van Dieren, S.; Gisbertz, S.S.; Henegouwen, M.I.v.B. Quantitative fluorescence-guided perfusion assessment of the gastric conduit to predict anastomotic complications after esophagectomy. Dis. Esophagus 2021, 34, doaa100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SPY-PHI SPY Portable Handheld Imaging System. 2021. Available online: https://www.stryker.com/us/en/endoscopy/products/spy-phi.html (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Galli, A.; Salerno, E.; Bramati, C.; Battista, R.A.; Melegatti, M.N.; Dolfato, E.; Fusca, G.; Pettirossi, C.; Gioffré, V.; Familiari, M.; et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence video-angiography for flap perfusion assessment in head and neck reconstruction: A prospective study. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 2025, 282, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiyama, D.; Kubo, Y.; Shigeno, T.; Sato, K.; Fujiwara, N.; Daiko, H.; Fujita, T. New quantitative blood flow assessment of gastric conduit with indocyanine green fluorescence in oesophagectomy: Prospective cohort study. BJS Open 2025, 9, zraf135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case | Age | Gender | Siewart Classification | Histology | Smoker | Type 2 Diabetes | Other Comorbidities | Staging | Neoadjuvant Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70 | M | I | SCC | No | No | HTN | ycT3N0 | CROSS |

| 2 | 68 | M | II | Adeno | Yes | Yes | Hyperlipidaemia | ycT2N0 | CROSS |

| 3 | 73 | F | I | SCC | No | No | HTN, AVR | ycT2N0 | CROSS |

| 4 | 62 | M | II | SCC | No | No | HTN | ycT3N2 | CROSS |

| 5 | 61 | F | II | Adeno | No | No | Depression | ycT3N1 | FLOT |

| 6 | 79 | F | II | Adeno | No | No | GORD, OSA, pulmonary hypertension, obesity | ycT3N0 | CROSS (Capecitabine only) |

| Case | Surgery | Approach | Native Perfusion Ratio | Relative Perfusion Ratio | Anastomotic Leak | Complications | 90-Day Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiological | Clinical | |||||||

| 1 | Tri-incisional Oesophagectomy (McKeown) | Open | 85–90% | 80–85% | No | No | Grade IV: pneumonia requiring prolonged intubation and tracheostomy | No |

| 2 | Ivor Lewis Oesophagectomy | Hybrid | 85–91% | 85–90% | No | No | Nil | No |

| 3 | Ivor Lewis oesophagectomy | Hybrid | 85–88% | 95–100% | No | No | Grade IV: pneumonia/mucous plugging requiring reintubation | No |

| 4 | Ivor Lewis Oesophagectomy | Hybrid | 85–90% | 95–100% | No | No | Grade II: pneumonia with antibiotic treatment | No |

| 5 | Ivor Lewis Oesophagectomy | Hybrid | 87–90% | 85–90% | No | No | Grade II: pneumonia with antibiotic treatment | No |

| 6 | Ivor Lewis Oesophagectomy | Open | 84–88% | 84–87% | No | No | Grade II: pneumonia with antibiotic treatment | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kyang, L.S.; Vivekanandamoorthy, N.; Li, S.; Goltsman, D.; Lorenzo, A.; Merrett, N. The Role of Quantitative Indocyanine Green Angiography with Relative Perfusion Ratio in the Assessment of Gastric Conduit Perfusion in Oesophagectomy: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010184

Kyang LS, Vivekanandamoorthy N, Li S, Goltsman D, Lorenzo A, Merrett N. The Role of Quantitative Indocyanine Green Angiography with Relative Perfusion Ratio in the Assessment of Gastric Conduit Perfusion in Oesophagectomy: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010184

Chicago/Turabian StyleKyang, Lee Shyang, Nurojan Vivekanandamoorthy, Simeng Li, David Goltsman, Aldenb Lorenzo, and Neil Merrett. 2026. "The Role of Quantitative Indocyanine Green Angiography with Relative Perfusion Ratio in the Assessment of Gastric Conduit Perfusion in Oesophagectomy: A Retrospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010184

APA StyleKyang, L. S., Vivekanandamoorthy, N., Li, S., Goltsman, D., Lorenzo, A., & Merrett, N. (2026). The Role of Quantitative Indocyanine Green Angiography with Relative Perfusion Ratio in the Assessment of Gastric Conduit Perfusion in Oesophagectomy: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010184