Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 and Myasthenic-like Symptom Complications in Two Relatives: A Coincidence or Spike Toxicity with Thymic Response in Predisposed Individuals? Two Clinical Cases with a Comprehensive Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

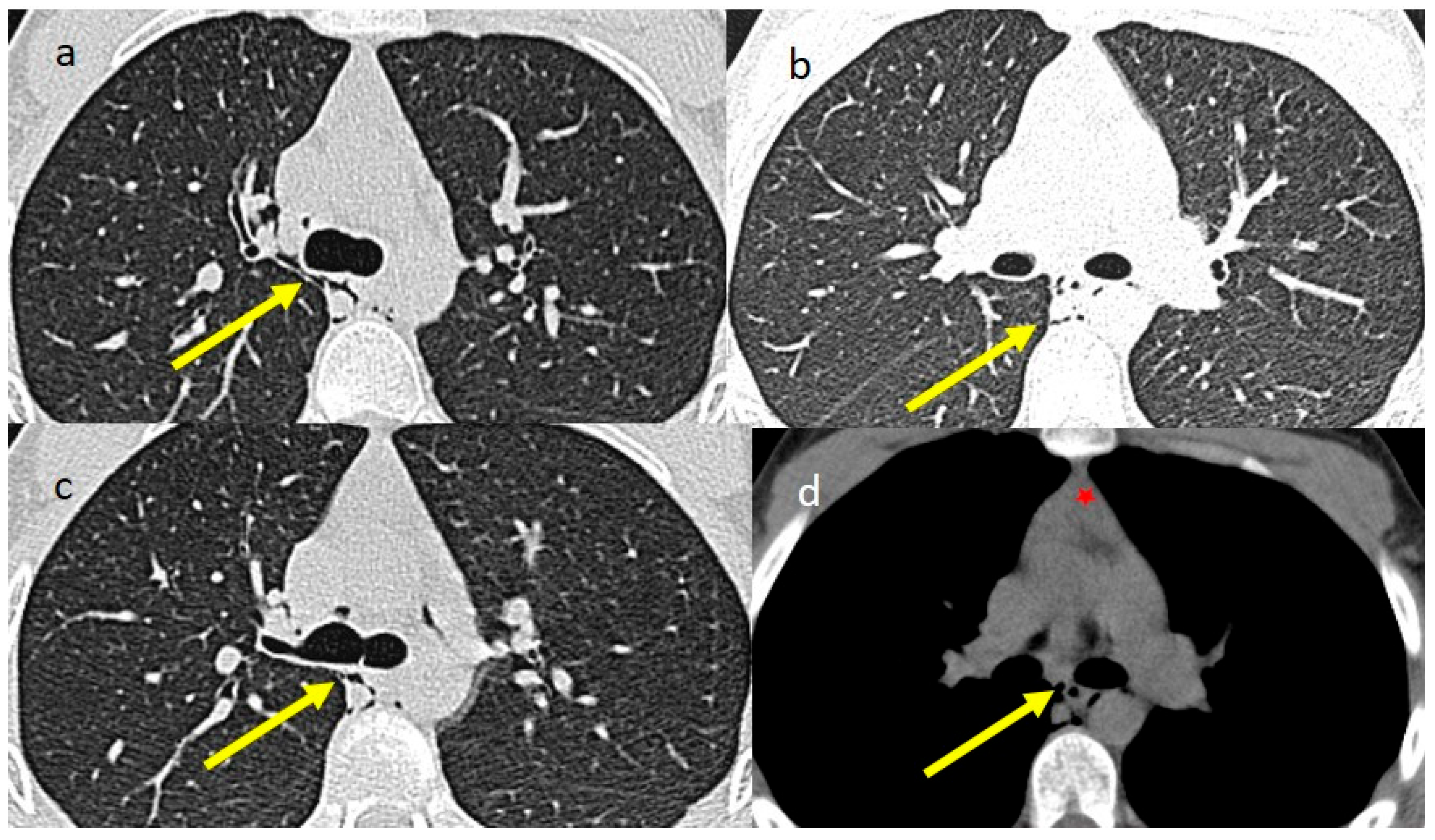

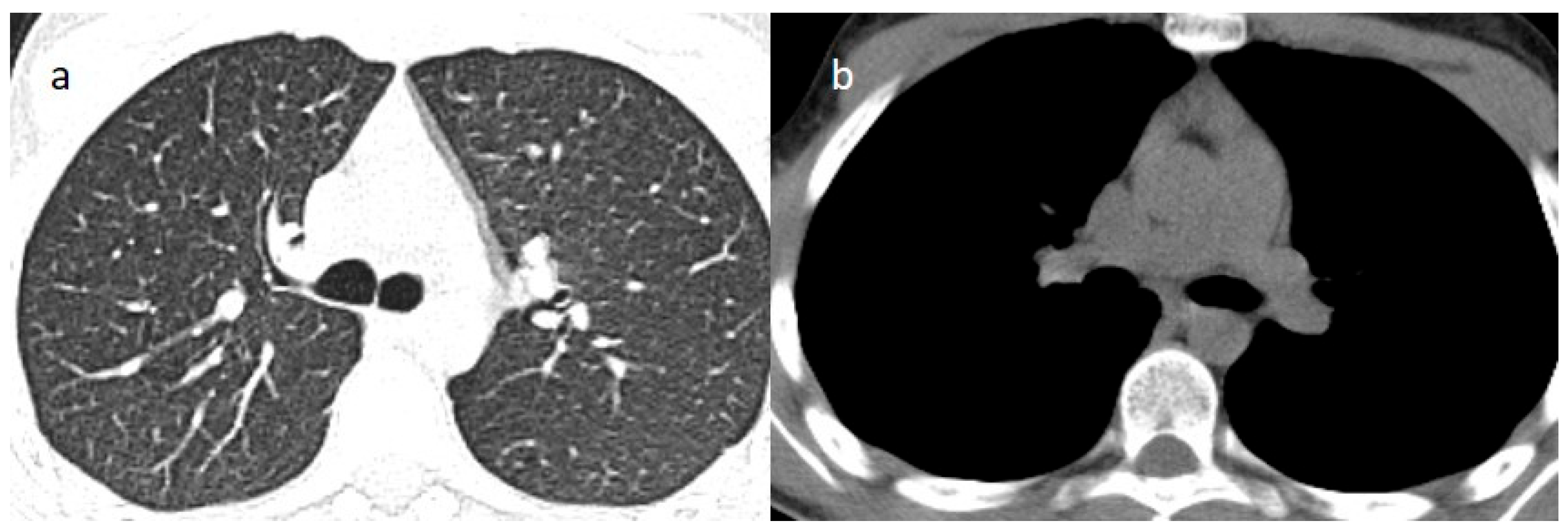

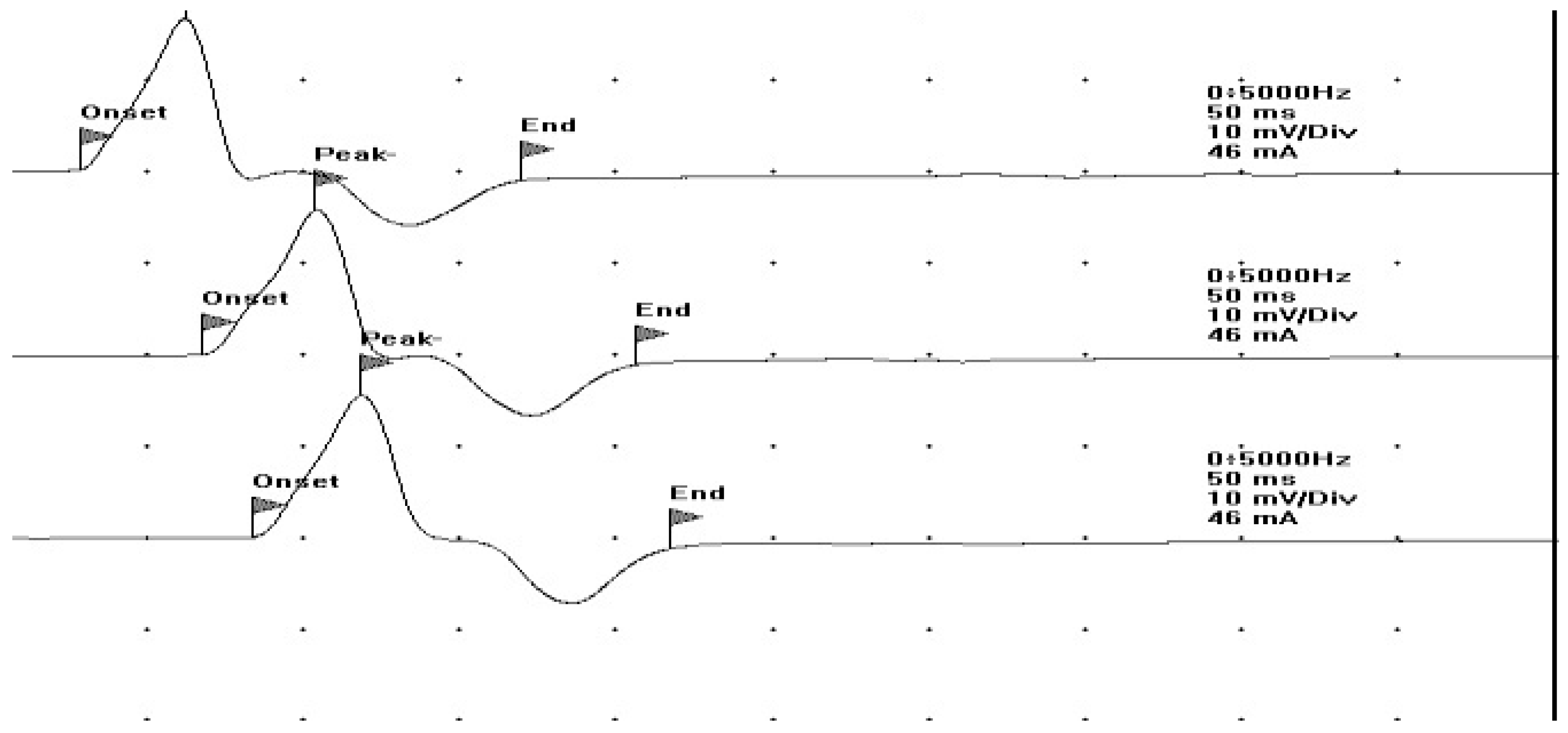

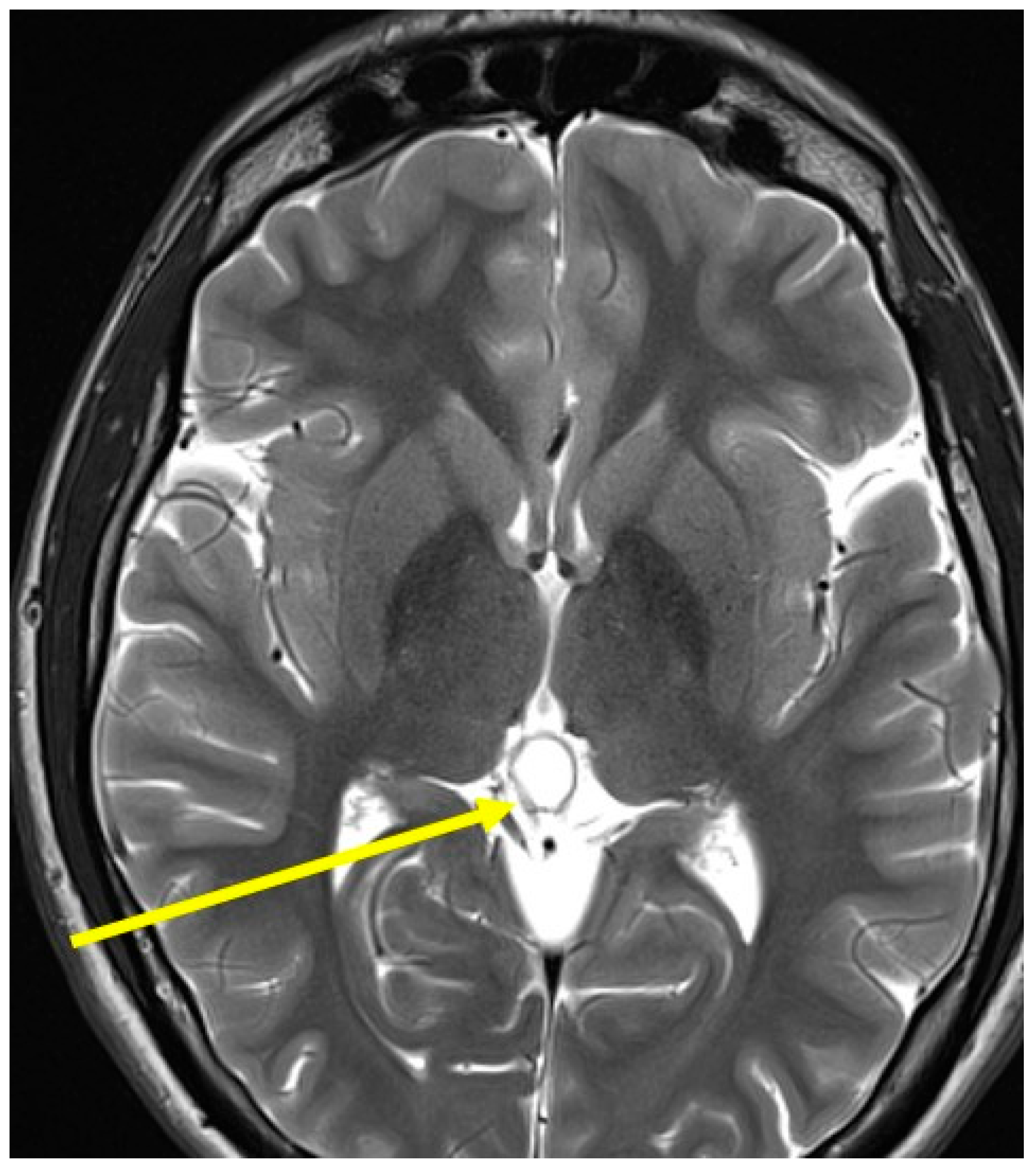

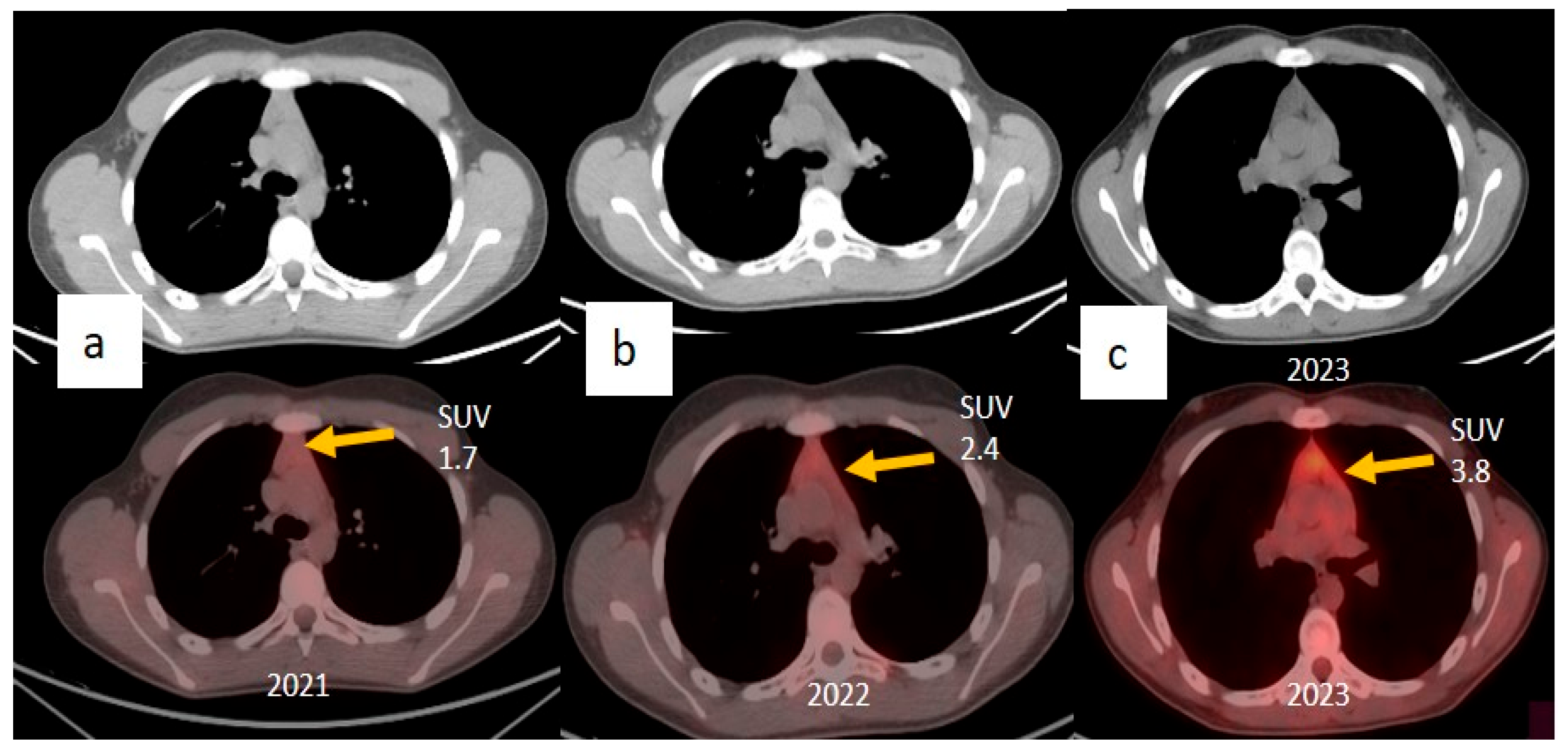

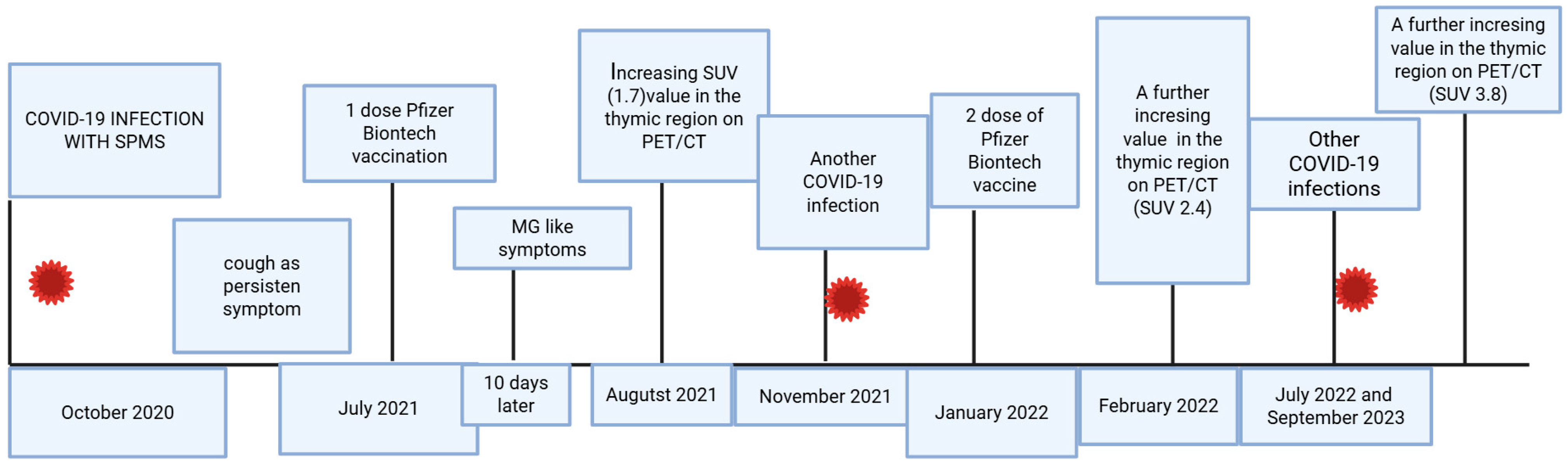

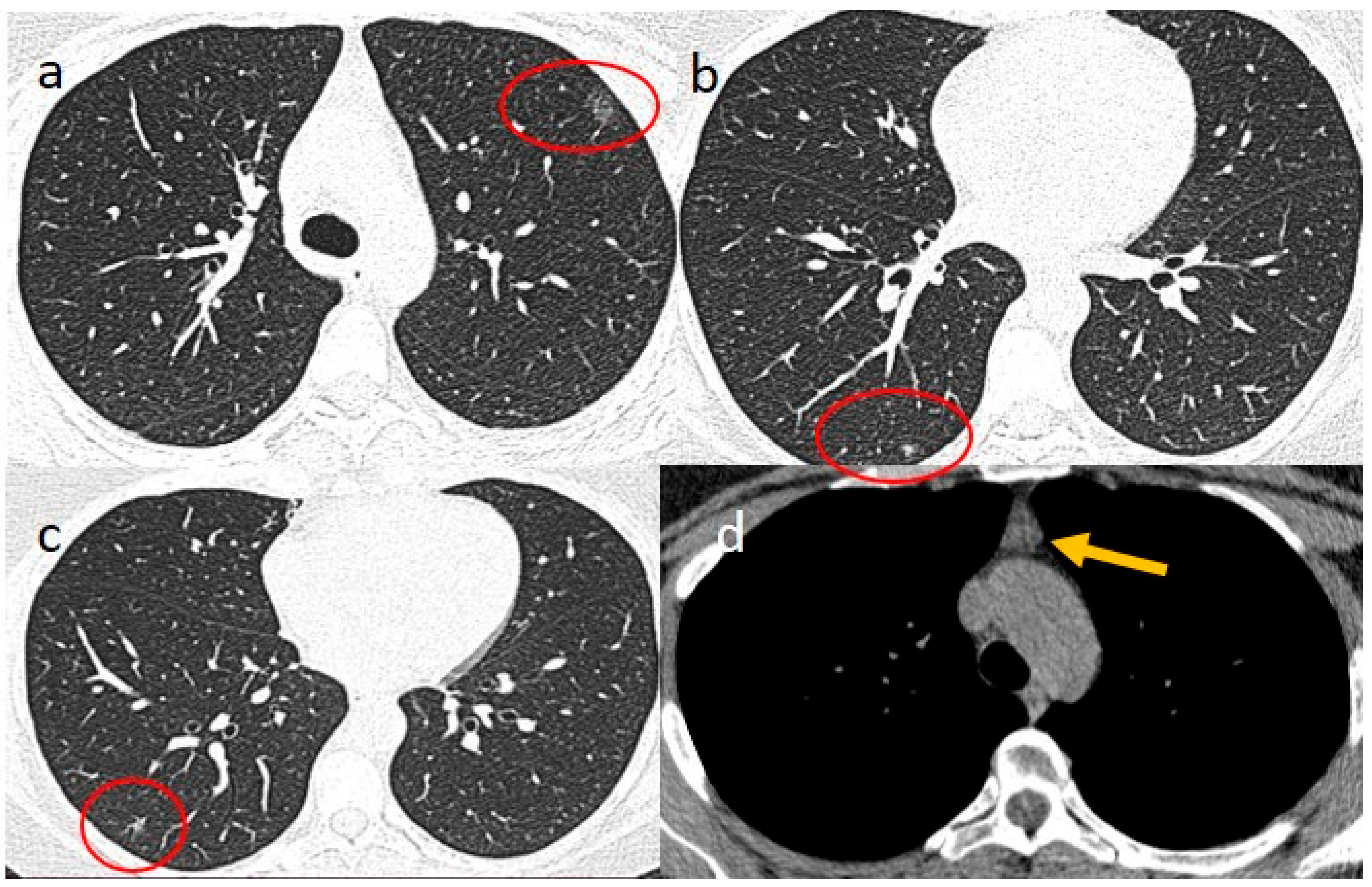

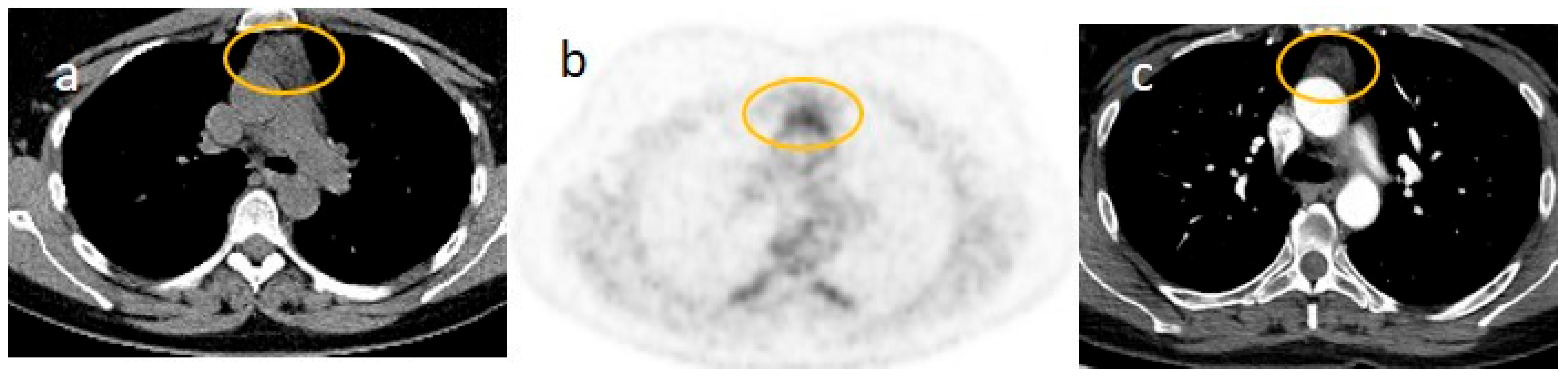

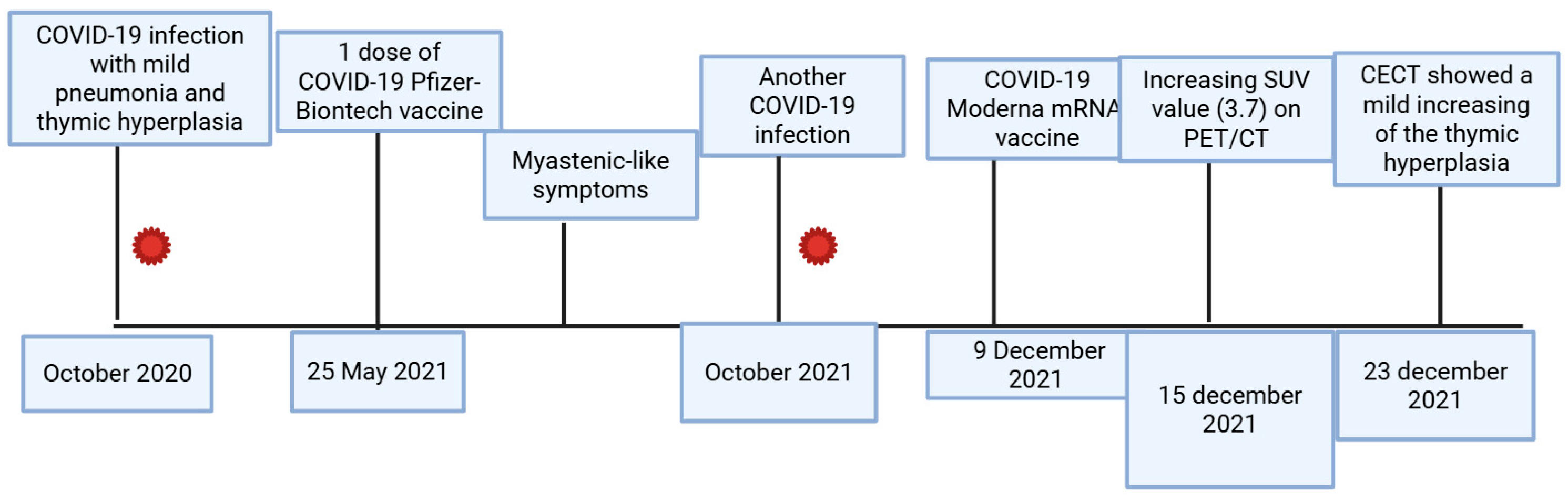

2. Case Presentations

3. Discussion

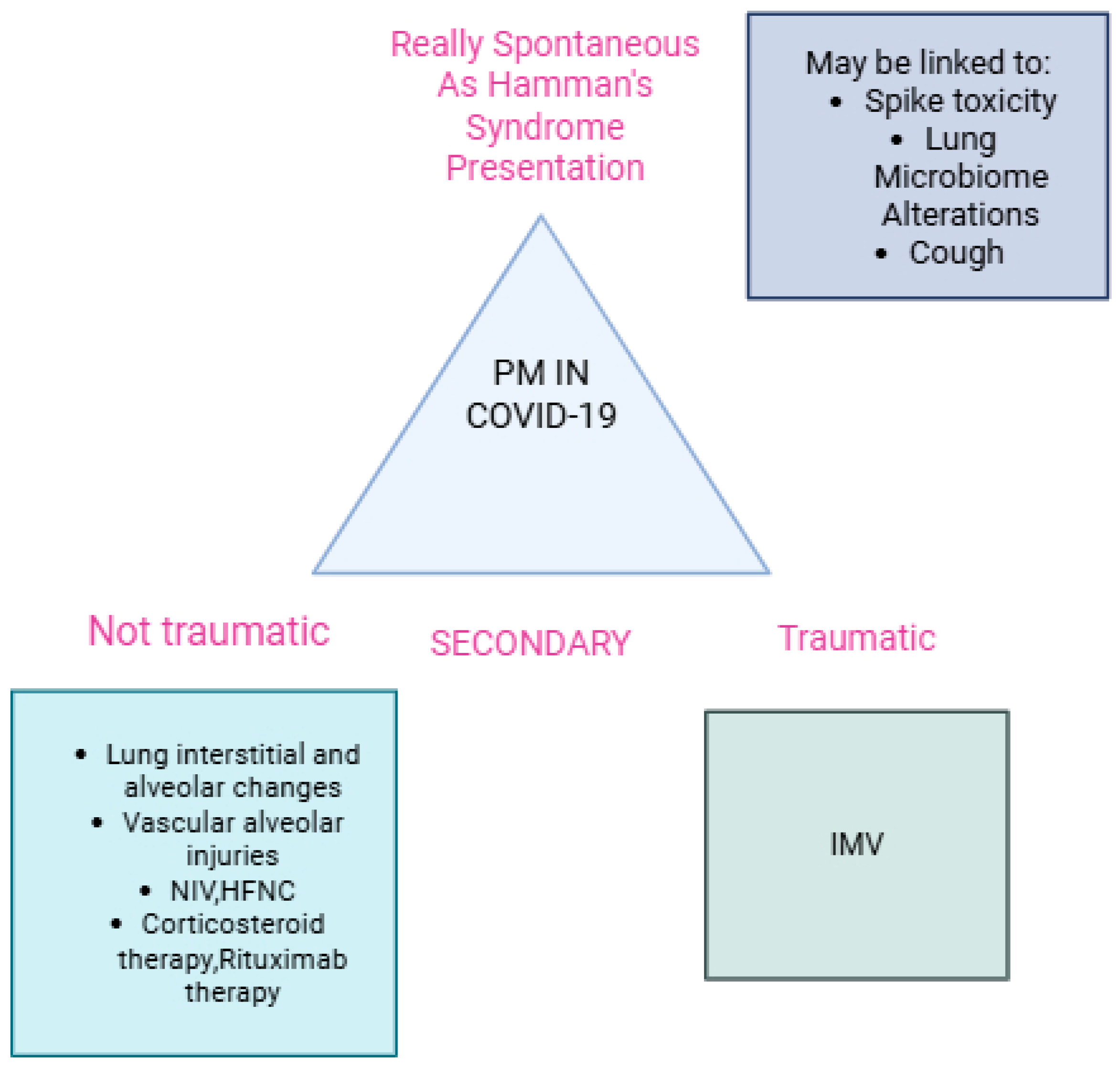

3.1. Secondary Non-Traumatic Pneumomediastinum Across Different COVID-19 and Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum as a Presentation of Hamman’s Syndrome

3.2. Thymic Hyperplasia in COVID-19 Infection and Vaccination and the Role of Multimodality Imaging

3.3. Myasthenic Syndrome After SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Vaccination

3.4. Long COVID (PASC) and Long Post-Acute COVID-19 Vaccine Syndrome (LPACVS)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moldovan, F.; Gligor, A.; Moldovan, L.; Bataga, T. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the orthopedic residents: A pan-Romanian survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Boon, S.S.; Wang, M.H.; Chan, R.W.; Chan, P.K. Genomic and evolutionary comparison between SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. J. Virol. Methods 2021, 289, 114032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado, L.L.; Bertelli, A.M.; Kamenetzky, L. Molecular features similarities between SARS-CoV-2, SARS, MERS and key human genes could favour the viral infections and trigger collateral effects. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldaria, A.; Conforti, C.; Di Meo, N.; Dianzani, C.; Jafferany, M.; Lotti, T.; Zalaudek, I.; Giuffrida, R. COVID-19 and SARS: Differences and similarities. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshta, A.S.; Mallah, S.I.; Al Zubaidi, K.; Ghorab, O.K.; Keshta, M.S.; Alarabi, D.; Abousaleh, M.A.; Salman, M.T.; Taha, O.E.; Zeidan, A.A.; et al. COVID-19 versus SARS: A comparative review. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Leung, Y.; Hui, J.; Hung, I.; Chan, V.; Leung, W.; Law, K.; Chan, C.; Chan, K.; Yuen, K. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Eur. Respir. J. 2004, 23, 802–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, U.; Medeiros, C.; Nanduri, A.; Kanoff, J.; Zarbiv, S.; Bonk, M.; Green, A. Understanding pneumomediastinum as a complication in patients with COVID-19: A case series. J. Investig. Med. High Impact Case Rep. 2022, 10, 23247096221127117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekkoth, S.M.; Naga, S.R.; Valsala, N.; Kumar, P.; Raja, R.S. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in H1N1 infection: Uncommon complication of a common infection. J. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb. 2019, 49, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganessane, E.; Devendiran, A.; Ramesh, S.; Uthayakumar, A.; Chandrasekar, V.; Ayyan, M. Pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 disease: Clinical review with emphasis on emergency management. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2023, 4, e12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, H.; Inokuma, S.; Nakayama, H.; Suzuki, M. Pneumomediastinum in dermatomyositis: Association with cutaneous vasculopathy. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2000, 59, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmers, D.H.; Hilal, M.A.; Bnà, C.; Prezioso, C.; Cavallo, E.; Nencini, N.; Natalini, G. Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in COVID-19: Barotrauma or lung frailty? ERJ Open Res. 2020, 6, 00385-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belletti, A.; Palumbo, D.; Zangrillo, A.; Fominskiy, E.V.; Franchini, S.; Dell’Acqua, A.; Marinosci, A.; Monti, G.; Vitali, G.; Colombo, S.; et al. Predictors of pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. J. Cardiothor. Vasc. Anesth. 2021, 35, 3642–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggialetti, N.; Piemonte, S.; Sperti, E.; Inchingolo, F.; Greco, S.; Lucarelli, N.M.; De Chirico, P.; Lofino, S.; Coppola, F.; Catacchio, C.; et al. Iatrogenic Barotrauma in COVID-19-Positive Patients: Is It Related to the Pneumonia Severity? Prevalence and Trends of This Complication Over Time. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberger, S.; Finkelstein, M.; Pagano, A.; Manna, S.; Toussie, D.; Chung, M.; Bernheim, A.; Concepcion, J.; Gupta, S.; Eber, C.; et al. Barotrauma in COVID 19: Incidence, pathophysiology, and effect on prognosis. Clin. Imaging 2022, 90, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetaj, N.; Garotto, G.; Albarello, F.; Mastrobattista, A.; Maritti, M.; Stazi, G.V.; Marini, M.C.; Caravella, I.; Macchione, M.; De Angelis, G.; et al. Incidence of pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum in 497 COVID-19 patients with moderate–severe ards over a year of the pandemic: An observational study in an Italian third level COVID-19 hospital. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaire, N.; Deshmukh, S.; Agarwal, E.; Mahale, N.; Khaladkar, S.; Desai, S.; Kulkarni, A. Pneumomediastinum: A marker of severity in COVID-19 disease. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, N.; Renzulli, M. The role of imaging in detecting and monitoring COVID-19 complications in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) setting. Anesthesiol. Periop. Sci. 2024, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, A.; Devarajan, A.; Sakata, K.K.; Qamar, S.; Sharma, M.; Morales, D.J.V.; Malinchoc, M.; Talaei, F.; Welle, S.; Taji, J.; et al. Pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax in coronavirus disease-2019: Description of a case series and a matched cohort study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marza, A.M.; Cindrea, A.C.; Petrica, A.; Stanciugelu, A.V.; Barsac, C.; Mocanu, A.; Critu, R.; Botea, M.O.; Trebuian, C.I.; Lungeanu, D. Non-Ventilated Patients with Spontaneous Pneumothorax or Pneumomediastinum Associated with COVID-19: Three-Year Debriefing across Five Pandemic Waves. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, D.; Zangrillo, A.; Belletti, A.; Guazzarotti, G.; Calvi, M.R.; Guzzo, F.; Pennella, R.; Monti, G.; Gritti, C.; Marmiere, M.; et al. A radiological predictor for pneumomediastinum/pneumothorax in COVID-19 ARDS patients. J. Crit. Care 2021, 66, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, F.; Rogliani, P.; Leonardis, F.; Sarmati, L.; Fabbi, E.; De Carolis, G.; La Rocca, E.; Vanni, G.; Ambrogi, V. Incidence of pneumomediastinum in COVID-19: A single-center comparison between 1st and 2nd wave. Respir. Investig. 2021, 59, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staiano, P.P.; Patel, S.; Green, K.R.; Louis, M.; Hatoum, H. A case series of secondary spontaneous pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax in severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Cureus 2022, 14, e22247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberal, M.A.; Akar, E.; Dikis, O.S.; Ay, M.O.; Demirci, H. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum incidence and clinical features in non-intubated patients with COVID-19. Clinics 2021, 76, e2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elabbadi, A.; Urbina, T.; Berti, E.; Contou, D.; Plantefève, G.; Soulier, Q.; Milon, A.; Carteaux, G.; Voiriot, G.; Fartoukh, M.; et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: A surrogate of P-SILI in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo, D.; Campochiaro, C.; Belletti, A.; Marinosci, A.; Dagna, L.; Zangrillo, A.; De Cobelli, F. Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum in non-intubated COVID-19 patients: Differences between first and second Italian pandemic wave. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 88, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfo, C.; Bonfiglio, M.; Spinetto, G.; Ferraioli, G.; Barlascini, C.; Nicolini, A.; Solidoro, P. Pneumomediastinum associated with severe pneumonia related to COVID-19: Diagnosis and management. Minerva Med. 2021, 112, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogna, B.; Bignardi, E.; Salvatore, P.; Alberigo, M.; Brogna, C.; Megliola, A.; Musto, L. Unusual presentations of COVID-19 pneumonia on CT scans with spontaneous pneumomediastinum and loculated pneumothorax: A report of two cases and a review of the literature. Heart Lung 2020, 49, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susai, C.J.; Banks, K.C.; Alcasid, N.J.; Velotta, J.B. A clinical review of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Mediastinum 2023, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macia, I.; Moya, J.; Ramos, R.; Morera, R.; Escobar, I.; Saumench, J.; Valerio PRivas, F. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2007, 31, 1110–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Silva, S.; Campbell-Quintero, S.; Díaz-Rodríguez, D.C.; Campbell-Quintero, S.; Castro-González, I.; Campbell-Quintero Sr, S.C.; Díaz-Rodríguez, D. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: A narrative review offering a new perspective on its definition and classification. Cureus 2025, 17, e81822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.H.; Kanne, J.P.; Ashizawa, K.; Biederer, J.; Castañer, E.; Fan, L.; Frauenfelder, T.; Ghaye, B.; Henry, T.S.; Huang, Y.-S.; et al. Best Practice: International Multisociety Consensus Statement for Post–COVID-19 Residual Abnormalities on Chest CT Scans. Radiology 2025, 316, e243374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keskin, Z.; Yeşildağ, M.; Özberk, Ö.; Ödev, K.; Ateş, F.; Bakdık, B.Ö.; Kardaş, Ş.Ç. Long-Term Effects of COVID-19: Analysis of Imaging Findings in Patients Evaluated by Computed Tomography from 2020 to 2024. Tomography 2025, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, M.; Barbu, E.C.; Chitu, C.E.; Buzoianu, M.; Petre, A.C.; Tiliscan, C.; Arama, S.S.; Arama, V.; Ion, D.A.; Olariu, M.C. Surviving COVID-19 and Battling Fibrosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study Across Three Pandemic Waves. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poerio, A.; Carlicchi, E.; Lotrecchiano, L.; Praticò, C.; Mistè, G.; Scavello, S.; Morsiani, M.; Zompatori, M.; Ferrari, R. Evolution of COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis–like residual changes over time—Longitudinal chest CT up to 9 months after disease onset: A single-center case series. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2022, 4, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajhi, N.N. Post-COVID-19 pulmonary fibrosis: An ongoing concern. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2023, 18, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesgards, J.F.; Cerdan, D.; Perronne, C. Do Long COVID and COVID Vaccine Side Effects Share Pathophysiological Picture and Biochemical Pathways? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.T.; Wu, K.; Cheng, Z.; He, M.; Hu, R.; Fan, N.; Tong, Y. Long COVID: The latest manifestations, mechanisms, and potential therapeutic interventions. MedComm 2020, 3, e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Zhang, P.; Ricciardi, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, C.; Qian, K.; Zhang, Y. Incidental mediastinal masses detected on chest computed tomography scans during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2025, 67, ezaf140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonaiuto, R.; Peddio, A.; Caltavituro, A.; Morra, R.; De Placido, P.; Tortora, M.; Pietroluongo, E.; Ottaviano, M.; De Placido, S.; Palmieri, G.; et al. AB010. Incidental discovery of thymic masses during syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. Mediastinum 2021, 5, AB010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellina, M.; Cè, M.; Cozzi, A.; Schiaffino, S.; Fazzini, D.; Grossi, E.; Oliva, G.; Papa, S.; Alì, M. Thymic Hyperplasia and COVID-19 Pulmonary Sequelae: A Bicentric CT-Based Follow-Up Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicioglu, B.; Bayav, M. Study of thymus volume and density in COVID-19 patients: Is there a correlation in terms of pulmonary CT severity score? Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2022, 53, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthria, G.; Baratto, L.; Adams, L.; Morakote, W.; Daldrup-Link, H.E. Increased Metabolic Activity of the Thymus and Lymph Nodes in Pediatric Oncology Patients After Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramdas, S.; Hum, R.M.; Price, A.; Paul, A.; Bland, J.; Burke, G.; Farrugia, M.; Palace, J.; Storrie, A.; Ho, P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and new-onset myasthenia gravis: A report of 7 cases and review of the literature. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2022, 32, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restivo, D.A.; Centonze, D.; Alesina, A.; Marchese-Ragona, R. Myasthenia gravis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 1027–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Tresckow, J.; von Tresckow, B.; Reinhardt, H.C.; Herrmann, K.; Berliner, C. Thymic hyperplasia after mRNA based COVID-19 vaccination. Radiol. Case Rep. 2021, 16, 3744–3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, T.; Nakazawa, S.; Ibe, T.; Shirabe, K. Vanishing mediastinal mass associated with mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A rare case report. AME Med. J. 2022, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Que, X.; Jiang, A.; Shi, D.; Lu, T.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Liu, C.; et al. The characteristics of new-onset myasthenia gravis after COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Virol. J. 2025, 22, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tereshko, Y.; Gigli, G.L.; Pez, S.; De Pellegrin, A.; Valente, M. New-onset myasthenia gravis after SARS-CoV-2 infection: Case report and literature review. J. Neurol. 2023, 270, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, C.G.; Cuciureanu, D.I.; Hodorog, D.N.; Grosu, C.; Cianga, P. Autoimmune myasthenia gravis and COVID-19. A case report-based review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 03000605231191025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Silva, B.; Saianda Duarte, M.; Rodrigues Alves, N.; Vicente, P.; Araújo, J. Seronegative Myasthenia Gravis: A Rare Disease Triggered by SARS-CoV-2 or a Coincidence? Cureus 2024, 16, e67511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Su, S.; Zhang, S.; Wen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Han, J.; Xie, N.; Liu, H.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination and Infection on the Exacerbation of Myasthenia Gravis. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgilio, E.; Tondo, G.; Montabone, C.; Comi, C. COVID-19 vaccination and late-onset myasthenia gravis: A new case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, A.H.; Samimisedeh, P.; Afshar, E.J.; Ayati, A.; Ghalehnovi, E.; Foroutani, L.; Khoshsirat, N.A.; Rastad, H. Clinical features and outcomes of Myasthenia Gravis associated with COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review and pooled analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e34890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbel, A.; Bishara, H.; Barnett-Griness, O.; Cohen, S.; Najjar-Debbiny, R.; Gronich, N.; Auriel, E.; Saliba, W. Association between COVID-19 vaccination and myasthenia gravis: A population-based, nested case–control study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 3868–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özenç, B.; Odabaşı, Z. New-onset myasthenia gravis following COVID-19 vaccination. Ann. Indian. Acad. Neurol. 2022, 25, 1224–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abna, Z.; Khanmoradi, Z.; Abna, Z. A new case of myasthenia gravis following COVID-19 Vaccination. Neuroimmunol. Rep. 2022, 2, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhus, N.E.; Tzartos, S.; Evoli, A.; Palace, J.; Burns, T.M.; Verschuuren, J.J.G.M. Myasthenia gravis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks, S.N.M.; Morse, I.M.; Ashraghi, M.; Vincent, A.; Waters, P.; Leite, M.I. Myasthenia gravis in 2025: Five new things and four hopes for the future. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannemaat, M.R.; Huijbers, M.G.; Verschuuren, J.J. Myasthenia gravis—Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2024, 200, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.R.D.V.P.; Kay, C.S.K.; Ducci, R.D.-P.; Utiumi, M.A.T.; Fustes, O.J.H.; Werneck, L.C.; Lorenzoni, P.J.; Scola, R.H. Triple-seronegative myasthenia gravis: Clinical and epidemiological characteristics. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2024, 82, 001–007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, P.M.; Kaminski, H.J.; Kusner, L.L. Thymic hyperplasia in myasthenia gravis: A narrative review. Mediastinum 2025, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semmler, A.; Mundorf, A.K.; Kuechler, A.S.; Schulze-Bosse, K.; Heidecke, H.; Schulze-Forster, K.; Schott, M.; Uhrberg, M.; Weinhold, S.; Lackner, K.J.; et al. Chronic fatigue and dysautonomia following COVID-19 vaccination is distinguished from normal vaccination response by altered blood markers. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholkmann, F.; May, C.A. COVID-19, post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS, “long COVID”) and post-COVID-19 vaccination syndrome (PCVS, “post-COVIDvac-syndrome”): Similarities and differences. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 246, 154497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.F.; Dallagnol, C.A.; Moulepes, T.H.; Hirota, C.Y.; Kutsmi, P.; dos Santos, L.V.; Pirich, C.L.; Picheth, G.F. Oxygen therapy alternatives in COVID-19: From classical to nanomedicine. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C.; Abdul, K.A.; Bodo, B.; Abdalla, A.; Zamora, A.C.; Abraham, J.; Ganti, S.S. A Case Series of Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum With/Without Pneumothorax in COVID-19. J. Investig. Med. High. Impact Case Rep. 2023, 11, 23247096231176216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, X. Lung microbiome: New insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannaki, M.; Antoniadis, A. Potential mechanisms of mediastinum involvement in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pneumon 2020, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Y.J.; Nikolaienko, S.I.; Dibrova, V.A.; Dibrova, Y.V.; Vasylyk, V.M.; Novikov, M.Y.; Gychka, S.G. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-mediated cell signaling in lung vascular cells. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2021, 137, 106823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.Y.; Chang, L.; Lin, S.M. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum after BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination in adolescents. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2023, 64, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holländer, G.A. Introduction: Thymus development and function in health and disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 2021, 43, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, F.; Vecchio, E.; Renna, M.; Iaccino, E.; Mimmi, S.; Caiazza, C.; Fiume, G. Insights into thymus development and viral thymic infections. Viruses 2019, 11, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, D.; Matsusako, M.; Kurihara, Y. Review of clinical and diagnostic imaging of the thymus: From age-related changes to thymic tumors and everything in between. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klug, M.; Strange, C.D.; Truong, M.T.; Kirshenboim, Z.; Ofek, E.; Konen, E.; Marom, E.M. Thymic imaging pitfalls and strategies for optimized diagnosis. RadioGraphics 2024, 44, e230091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, A.J.; Oliva, I.; Honarpisheh, H.; Rubinowitz, A. A tour of the thymus: A review of thymic lesion. Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2015, 66, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, T.; Sholl, L.M.; Gerbaudo, V.H.; Hatabu, H.; Nishino, M. Imaging characteristics of pathologically proven thymic hyperplasia: Identifying features that can differentiate true from lymphoid hyperplasia. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2014, 202, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Singhal, A.; Kumar, A.; Bal, C.; Malhotra, A.; Kumar, R. Evaluation of thymic tumors with 18F-FDG PET-CT: A pictorial review. Acta Radiol. 2013, 54, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackman, J.B.; Wu, C.C. MRI of the thymus. AJR AM J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, W15–W20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenish, D.; Evans, C.J.; Khine, C.K.; Rodrigues, J.C.L. The thymus: What’s normal and what’s not? Problem-solving with MRI. Clin. Radiol. 2023, 78, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; I, H.; Kim, S.-J.; Pak, K.; Cho, J.S.; Jeong, Y.J.; Lee, C.H.; Chang, S. Initial experience of 18F-FDG PET/MRI in thymic epithelial tumors: Morphologic, functional, and metabolic biomarkers. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2016, 41, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Thomas, R.; Oh, J.; Su, D.M. Thymic aging may be associated with COVID-19 pathophysiology in the elderly. Cells 2021, 10, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvelier, P.; Roux, H.; Couëdel-Courteille, A.; Dutrieux, J.; Naudin, C.; de Muylder, B.C.; Cheynier, R.; Squara, P.; Marullo, S. Protective reactive thymus hyperplasia in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care 2021, 25, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Melo, B.P.; da Silva, J.A.M.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Palmeira, J.D.F.; Saldanha-Araujo, F.; Argañaraz, G.A.; Argañaraz, E.R. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Long COVID—Part 1: Impact of Spike Protein in Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Long COVID Syndrome. Viruses 2025, 17, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, G.; Alagna, L.; Alteri, C.; Palomba, E.; Tonizzo, A.; Pastena, A.; Muscatello, A.; Gori, A.; Bandera, A. Gut and airway microbiota dysbiosis and their role in COVID-19 and long-COVID. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1080043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gang, J.; Wang, H.; Xue, X.; Zhang, S. Microbiota and COVID-19: Long-term and complex influencing factors. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 963488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliman-Sturdza, O.A.; Hamamah, S.; Iatcu, O.C.; Lobiuc, A.; Bosancu, A.; Covasa, M. Microbiome and Long COVID-19: Current Evidence and Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Agrawal, D.K. Role of Gut Microbiota in Long COVID: Impact on Immune Function and Organ System Health. Arch. Microbiol. Immunol. 2025, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halma, M.; Varon, J. Breaking the silence: Recognizing post-vaccination syndrome. Heliyon 2025, 11, e43478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, P.I.; Lefringhausen, A.; Turni, C.; Neil, C.J.; Cosford, R.; Hudson, N.J.; Gillespie, J. ‘Spikeopathy’: COVID-19 spike protein is pathogenic, from both virus and vaccine mRNA. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Swank, Z.; Bartsch, Y.C.; Burns, M.D.; Kane, A.; Boribong, B.P.; Davis, J.P.; Loiselle, M.; Novak, T.; Senussi, Y.; et al. Circulating spike protein detected in post–COVID-19 mRNA vaccine myocarditis. Circulation 2023, 147, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, B.K.; Yogendra, R.; Francisco, E.B.; Guevara-Coto, J.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; Osgood, E.; Bream, J.; Kreimer, M.; Jeffers, D.; et al. Detection of S1 spike protein in CD16+ monocytes up to 245 days in SARS-CoV-2-negative post-COVID-19 vaccine syndrome (PCVS) individuals. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2025, 21, 2494934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, M.; Bellavite, P.; Fazio, S.; Di Fede, G.; Tomasi, M.; Belli, D.; Zanolin, E. Autoantibodies targeting G-Protein-Coupled receptors and RAS-related molecules in post-acute COVID vaccination syndrome: A retrospective case series study. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgatle, M.M.; Lawal, I.O.; Mashabela, G.; Boshomane, T.M.G.; Koatale, P.C.; Mahasha, P.W.; Ndlovu, H.; Vorster, M.; Rodrigues, H.G.; Zeevaart, J.R.; et al. COVID-19 is a multi-organ aggressor: Epigenetic and clinical marks. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 752380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Laboratory Parameters | Value (Units) | Reference Value |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 15.00 | 13.5–17.5 |

| Neutrophils | 2700/mcL | 2000–7000 |

| Lymphocytes | 1800/mcL | 1000–4000 |

| C-reactive protein | 1 mg/L | <5 |

| D-Dimer | 0.5 mg/L | <0.5 |

| Laboratory Parameters | Value (Units) | Reference Value |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 13.3 | 13.5–17.5 |

| Neutrophils | 4000/mcL | 2000–7000 |

| Lymphocytes | 4000/mcL | 1000–4000 |

| C-reactive protein | 0.05 mg/L | <5 |

| D-Dimer | 1 mg/L | <0.5 |

| PMS in Non-MV COVID-19 Patient Case-Studies: First Author and Reference | COVID-19 Wave Period of the Time | N of Patients Evaluated | Causes of Non-MV-PM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gulati et al. [7] | January 2020 to April 2021 | 37 | 23 HFNC and NIV; 11 without NIV 4 without NIV/HFNC |

| Tetaj et al. [15] | April 2020 to April 2021 | 2480 | 221 NIV 4 patients without NIV |

| Khaire et al. [16] | May 2020 to May 2021 | 2600 during the 1st wave and 3089 during the 2nd wave | SPM 26 during the 1st wave; 40 during the 2nd wave; 30 NIV 13 HFNC 13 O2 |

| Tekin et al. [18] | April 2020 to January 2022 | 6637 | 34 NIV 39 HFNC 33 no high-pressure respiratory support |

| Marza et al. [19] | March 2020 to October 2022 | 190 | SP-SPM: 15 in wave 1; 32 in wave 2; 46 in wave 3; 29 in wave 4; 68 in the wave 5. |

| Palumbo et al. [20] | February 2020 to December 2021 | 221 | 20 SPM |

| Tacconi et al. [21] | 1st and 2nd epidemic waves | 687 | 7 NIV 2 unassisted breathing |

| Staiano et al. [22] | January 2020 to November 2020 | 500 | 5 HFNC |

| Haberal et al. [23] | April 2020 to October 2020 | 38,492 | 7 SPM O2 |

| Elabaddi et al. [24] | August 2020 to April 2021 | 549 | 21 NIV |

| Palumbo et al. [25] | March 2020 to June January 2021 | 1151 in the 1st pandemic wave; 1484 in the 2nd pandemic wave | 1 SPM in the 1st wave and 13 in the 2nd wave; 8 CPAP in the 2nd wave 6 O2 All patients had corticosteroid therapy |

| Gandolfo et al. [26] | October 2021 to January 2021 | 111 | 11 NIV 6 HFNC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brogna, B.; Nunziata, M.; Urciuoli, L.; Romano, A.; Laporta, A.; Brogna, C. Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 and Myasthenic-like Symptom Complications in Two Relatives: A Coincidence or Spike Toxicity with Thymic Response in Predisposed Individuals? Two Clinical Cases with a Comprehensive Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010159

Brogna B, Nunziata M, Urciuoli L, Romano A, Laporta A, Brogna C. Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 and Myasthenic-like Symptom Complications in Two Relatives: A Coincidence or Spike Toxicity with Thymic Response in Predisposed Individuals? Two Clinical Cases with a Comprehensive Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010159

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrogna, Barbara, Mariagrazia Nunziata, Luigi Urciuoli, Annamaria Romano, Antonietta Laporta, and Claudia Brogna. 2026. "Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 and Myasthenic-like Symptom Complications in Two Relatives: A Coincidence or Spike Toxicity with Thymic Response in Predisposed Individuals? Two Clinical Cases with a Comprehensive Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010159

APA StyleBrogna, B., Nunziata, M., Urciuoli, L., Romano, A., Laporta, A., & Brogna, C. (2026). Spontaneous Pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 and Myasthenic-like Symptom Complications in Two Relatives: A Coincidence or Spike Toxicity with Thymic Response in Predisposed Individuals? Two Clinical Cases with a Comprehensive Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010159