Modified 3D-Controlled Inside-Out Compression Screw Fixation Technique in Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Narrative Review and Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

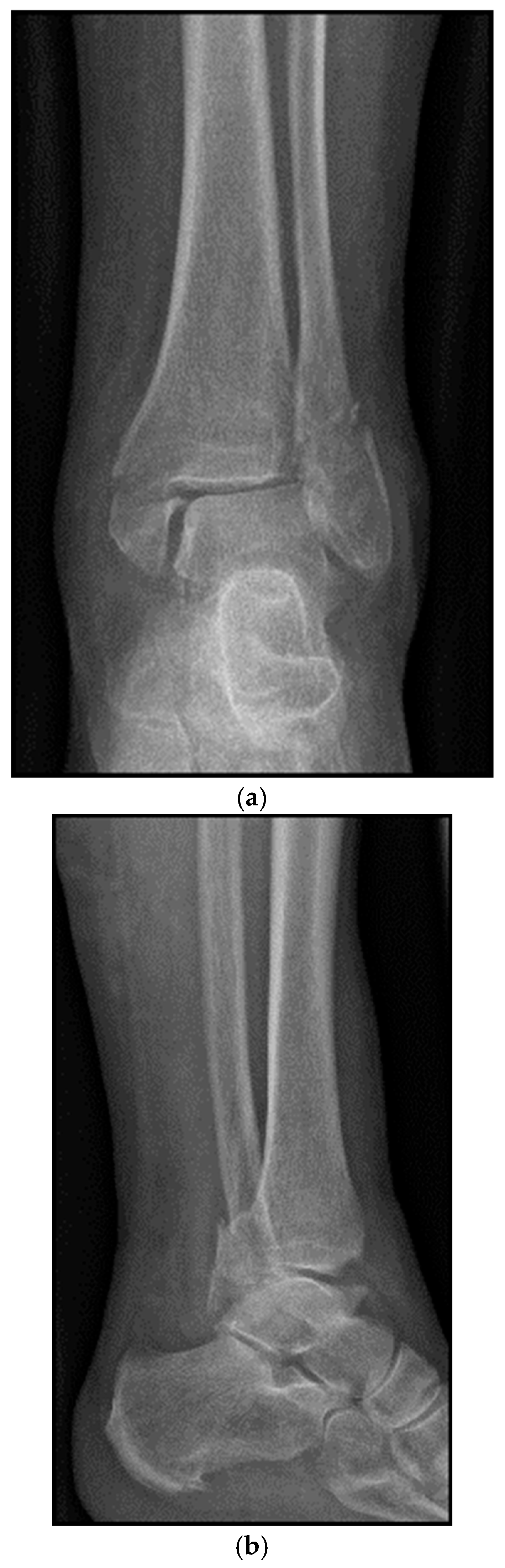

2. Preoperative Diagnostics

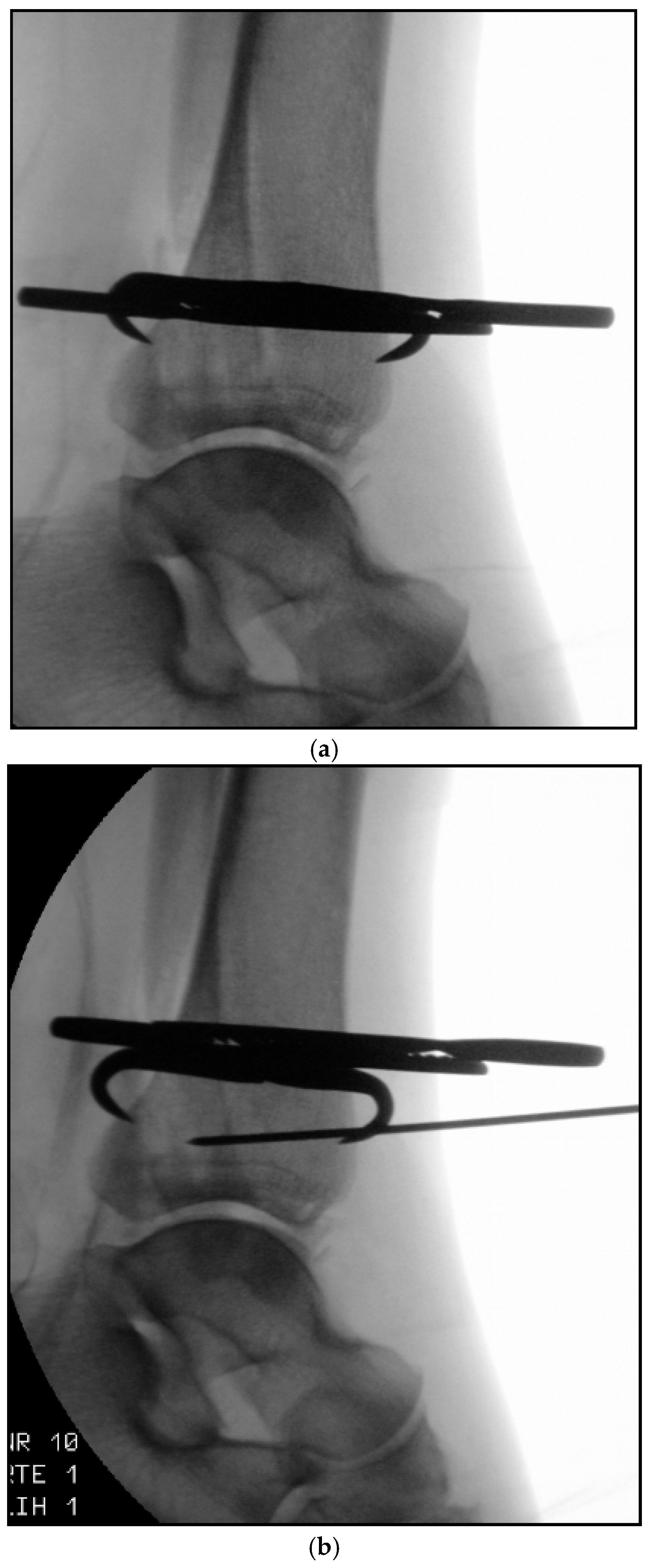

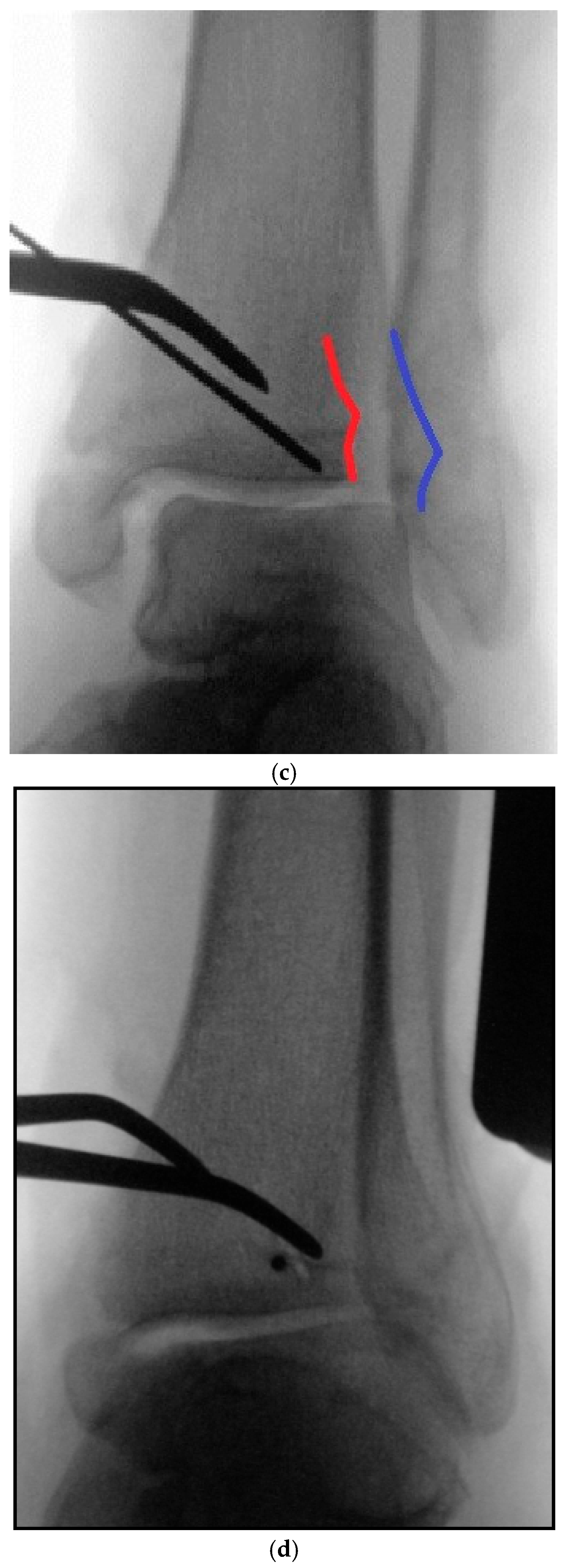

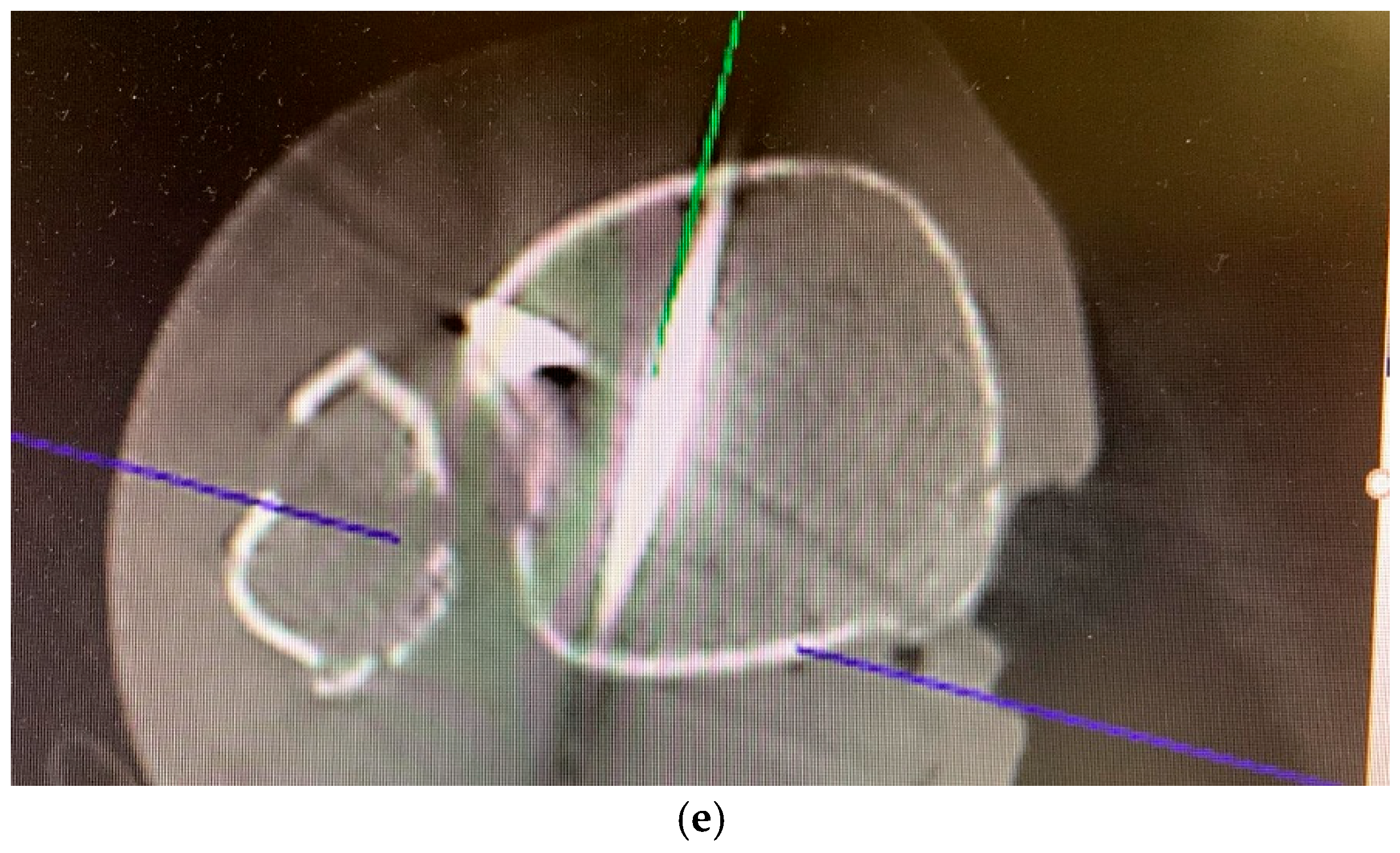

3. Intraoperative 3D Fluoroscopic Control

4. Classification

5. Case Description

5.1. Surgical Considerations

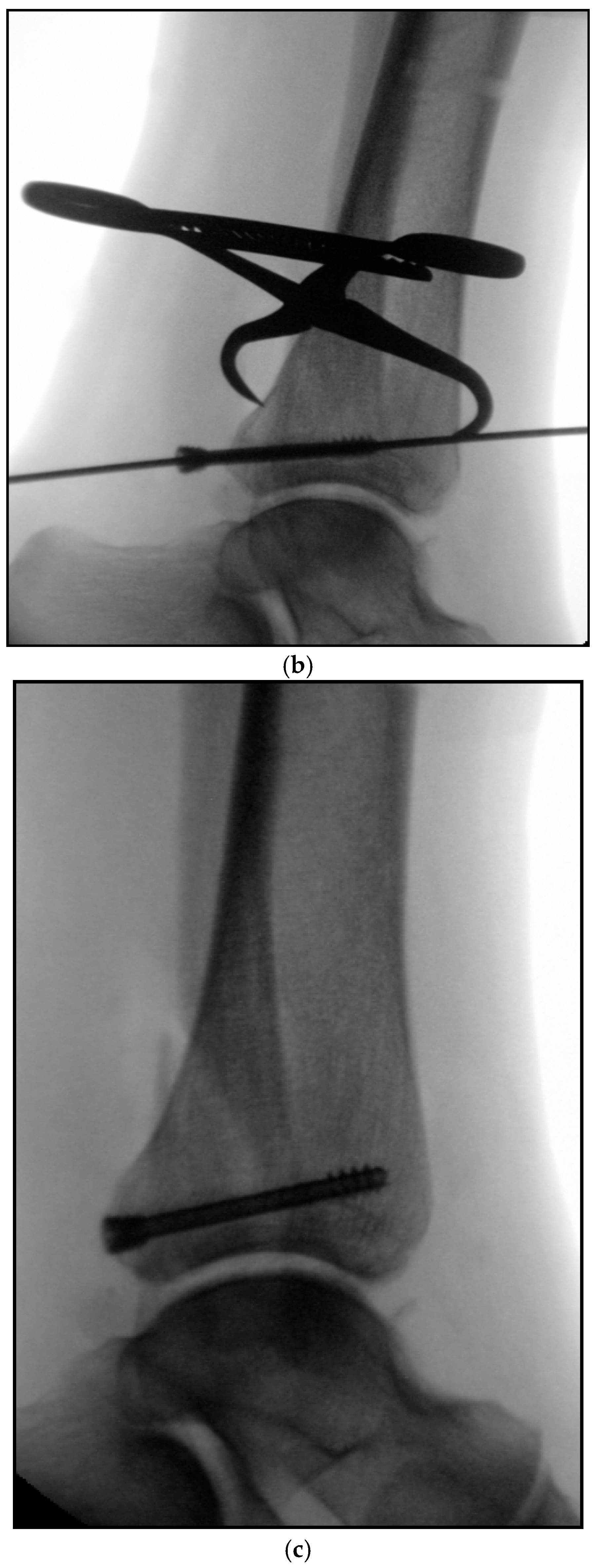

5.2. Inside-Out Fixation of the Posterior Malleolus Using a Headless Double-Threaded Compression Screw

5.3. Specific Considerations on Double-Threaded Screws in the Management of Complex Ankle Fractures

5.4. Medial Malleolar Cancellous Screw Fixation Using the Modified Posteromedial Approach

5.5. Reamed Intramedullary Locking Nail Fixation of the Distal Fibular Fracture

6. Advantages of the Inside-Out Technique

7. Potential Risks and Complications

8. Postoperative Management

9. Follow-Up

10. Ongoing and Future Research

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mittlmeier, T.; Saß, M.; Randow, M.; Wichelhaus, A. Fracture of the Posterior Malleolus: A Paradigm Shift. Unfallchirurg 2021, 124, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammelt, S.; Manke, E. Syndesmosis Injuries at the Ankle. Unfallchirurg 2018, 121, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, M.J.; Brodsky, A.; Briggs, S.M.; Nielson, J.H.; Lorich, D.G. Fixation of Posterior Malleolar Fractures Provides Greater Syndesmotic Stability. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2006, 447, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumbach, S.F.; Böcker, W.; Polzer, H. Arthroscopically Assisted Fracture Treatment and Open Reduction of the Posterior Malleolus: New Strategies for Management of Complex Ankle Fractures. Unfallchirurg 2020, 123, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumbach, S.F.; Böcker, W.; Polzer, H. Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of Posterior Malleolus Fractures. Oper. Orthop. Traumatol. 2021, 33, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Rüden, C.; Hackl, S.; Woltmann, A.; Friederichs, J.; Bühren, V.; Hierholzer, C. The Postero-Lateral Approach—An Alternative to Closed Anterior–Posterior Screw Fixation of a Dislocated Postero-Lateral Fragment of the Distal Tibia in Complex Ankle Fractures. Z. Orthop. Unfall. 2015, 153, 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Tonetti, J.; Boudissa, M.; Kerschbaumer, G.; Seurat, O. Role of 3D intraoperative imaging in orthopedic and trauma surgery. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2020, 106, S19–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miksch, R.C.; Herterich, V.; Barg, A.; Böcker, W.; Polzer, H.; Baumbach, S.F. Open Reduction and Internal Fixation of the Posterior Malleolus Fragment in Ankle Fractures Improves the Patient-Rated Outcome: A Systematic Review. Foot Ankle Int. 2023, 44, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoníček, J.; Rammelt, S.; Kostlivý, K.; Vaněček, V.; Klika, D.; Trešl, I. Anatomy and Classification of the Posterior Tibial Fragment in Ankle Fractures. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2015, 135, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoníček, J.; Rammelt, S.; Tuček, M. Posterior Malleolar Fractures: Changing Concepts and Recent Developments. Foot Ankle Clin. 2017, 22, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammelt, S.; Bartoníček, J. Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Rev. 2020, 8, e19.00207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massri-Pugin, J.; Morales, S.; Serrano, J.; Mery, P.; Filippi, J.; Villa, A. Percutaneous Fixation of Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Contemporary Review. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2024, 9, 24730114241256371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keil, H.; Beisemann, N.; Swartman, B.; Schnetzke, M.; Vetter, S.Y.; Grützner, P.A.; Franke, J. Intraoperative Revision Rates Due to Three-Dimensional Imaging in Orthopedic Trauma Surgery: Results of a Case Series of 4721 Patients. Eur. J Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2023, 49, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammelt, S.; Boszczyk, A. Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Ankle Fractures: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS Rev. 2018, 6, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennings, R.; Souleiman, F.; Heilemann, M.; Hennings, M.; Klengel, A.; Osterhoff, G.; Hepp, P.; Ahrberg, A.B. Suture Button versus Syndesmotic Screw in Ankle Fractures—Evaluation with 3D Imaging-Based Measurements. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halm, J.A.; Beerekamp, M.S.H.; de Muinck-Keijzer, R.J.; Beenen, L.F.M.; Maas, M.; Goslings, J.C.; Schepers, T. Intraoperative Effect of 2D vs. 3D Fluoroscopy on Quality of Reduction and Patient-Related Outcome in Calcaneal Fracture Surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2020, 41, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stengel, D.; Wich, M.; Ekkernkamp, A.; Spranger, N. Intraoperative 3D Imaging: Diagnostic Accuracy and Therapeutic Benefits. Unfallchirurg 2016, 119, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duschek, S.; Leucht, A.K.; Aregger, F.; Meier, C. Intraoperative 3D-Fluoroscopy Increases Accuracy of Syndesmotic Reduction in Ankle Fractures with Syndesmotic Instability. Br. J. Surg. 2023, 110, znad178.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, F.T.; Gaube, F.P.; Böcker, W.; Polzer, H.; Baumbach, S.F. Value of Intraoperative 3D Imaging on the Quality of Reduction of the Distal Tibiofibular Joint When Using a Suture-Button System. Foot Ankle Int. 2023, 44, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Brunk, M.; Wichelhaus, A.; Mittlmeier, T.; Rotter, R. Intraoperative Three-Dimensional Imaging in Ankle Syndesmotic Reduction. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carelsen, B.; Haverlag, R.; Ubbink, D.T.; Luitse, J.S.; Goslings, J.C. Does Intraoperative Fluoroscopic 3D Imaging Provide Extra Information for Fracture Surgery? Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2008, 128, 1419–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhont, T.; Huyghe, M.; Peiffer, M.; Hagemeijer, N.; Karaismailoglu, B.; Krahenbuhl, N.; Audenaert, E.; Burssens, A. Ins and Outs of the Ankle Syndesmosis from a 2D to 3D CT Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortekangas, T.; Pakarinen, H.; Flinkkilä, T.; Lepojärvi, S.; Ohtonen, P.; Niinimäki, J. The Use of Intraoperative Comparative Fluoroscopy Allows for Assessing Sagittal Reduction and Predicting Syndesmosis Reduction in Ankle Fractures. Injury 2021, 52, 3095–3103. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, E.; Terstegen, J.; Kleinertz, H.; Weel, H.; Frosch, K.-H.; Barg, A.; Schlickewei, C. Established Classification Systems of Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Systematic Literature Review. Unfallchirurgie 2023, 126, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamin, K.; Kleber, C.; Marx, C.; Schaser, K.D.; Rammelt, S. Minimally Invasive Fixation of Distal Fibular Fractures with Intramedullary Nailing. Oper. Orthop. Traumatol. 2021, 33, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenhorst, D.; Terblanche, I.; Ferreria, N.; Burger, M.C. Intramedullary Fixation versus Anatomically Contoured Plating of Unstable Ankle Fractures: A Randomized Control Trial. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauge-Hansen, N. Fractures of the Ankle II: Combined Experimental/Surgical and Experimental Roentgenologic Investigation. Arch. Surg. 1950, 60, 957–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.; Garlick, N.; McCarthy, I.; Grechenig, S.; Grechenig, W.; Smitham, P. Screw Fixation of Medial Malleolar Fractures: A Cadaveric Biomechanical Study Challenging the Current AO Philosophy. Bone Jt. J. 2013, 95, 1662–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, M.; Messerly, C.; Boffeli, T.; Sorensen, T. Medial Malleolar Screw Length to Achieve Thread Purchase in the Dense Bone of the Tibial Epiphyseal Scar Location Based on CT Model. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2022, 61, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çabuk, H.; İmren, Y.; Dedeoğlu, S.S.; Kır, M.Ç.; Gürbüz, S.; Gürbüz, H. The Epiphyseal Scar Joint Line Distance and Age Are Important Factors in Determining the Optimal Screw Length for Medial Malleoli Fractures. Injury 2019, 50, 1000–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, A.Ç.; Çabuk, H.; Dedeoğlu, S.S.; Saygılı, M.S.; Adaş, M.; Büyükkurt, C.D.; Gürbüz, H.; Çakar, M.; Tekin, Z.N. Anterograde Headless Cannulated Screw Fixation in the Treatment of Medial Malleolar Fractures: Evaluation of a New Technique and Its Outcomes. Med. Princ. Pract. 2016, 25, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Lin, C.C.; Hou, C.H.; Chang, C.H.; Cheng, C.L. A Biomechanical Comparison of Posterior Malleolar Fracture Fixation Constructs. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandala, M.; Shaunak, S.; Kreitmair, P.; Phadnis, J.; Guryel, E. Biomechanical Comparison of Headless Compression Screws versus Independent Locking Screw for Intra-Articular Fractures. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2024, 34, 1319–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aamir, J.; Jamal, F.; Ali, M.H. A Retrospective Case Series of Single-Screw vs. Dual-Screw Fixation for Ankle Fractures: Radiographic and Short-Term Clinical Outcomes. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2024, 9, 24730114241291064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, N.; Mishra, S.S.; Mohanty, A.; Sahoo, D. Functional and Radiological Outcomes of Medial Malleolus Fracture Fixation Using Headless Compression Screws. Cureus 2025, 17, e83869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, B.E.; Karnyski, S.; DiStefano, D.A.; Soin, S.P.; Flemister, A.S.; Ketz, J.P. Reduction of Posterior Malleolus Fractures with Open Fixation Compared to Percutaneous Treatment. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2023, 8, 24730114231200485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.U.; Müller, J.; Marx, S.; Matthes, M.; Nowak, S.; Schroeder, H.W.S.; Pillich, D.T. Biomechanical Comparison of Three Different Compression Screws for Treatment of Odontoid Fractures: Evaluation of a New Screw Design. Clin. Biomech. 2020, 77, 105049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, B.; Patel, N.H.; Nayar, S.K. Plate versus Intramedullary Nail Fixation for Distal Fibula Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Cureus 2025, 17, e90130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, T.B.; Box, M.W.; Marchese, C.R.; Lam, A.; Stegelmann, S.; Riehl, J.T. Comparison of Fibula Plating versus Fibula Nailing: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of All Current Comparative Literature. J. Orthop. Surg. 2025, 33, 10225536251345196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; McKissack, H.; Yu, J.; He, J.K.; Montgomery, T.; Moraes, L.; Alexander, B.; Shah, A. Anatomic Structures at Risk in Anteroposterior Screw Fixation of Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Cadaver Study. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021, 27, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Charles, L.; Ritchie, J. A Complication of Posterior Malleolar Fracture Fixation. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2016, 55, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenge, K.B.; Idusuyi, O.B. Technique Tip: Percutaneous Screw Fixation of Posterior Malleolar Fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2006, 27, 650–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, T.; Whitworth, N.; Platt, S. Defining a Safe Zone for Percutaneous Screw Fixation of Posterior Malleolar Fractures. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2021, 60, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerwonka, N.; Momenzadeh, K.; Stenquist, D.S.; O’Donnell, S.; Kwon, J.Y.; Nazarian, A.; Miller, C.P. Anatomic Structures at Risk during Posterior to Anterior Percutaneous Screw Fixation of Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Cadaveric Study. Foot Ankle Spec. 2022, 15, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkinson, R.; Sanders, D.; Macleod, M.; Domonkos, A.; Lydestadt, J. Intraoperative Diagnosis of Syndesmosis Injuries in External Rotation Ankle Fractures. J. Orthop. Trauma 2005, 19, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfarth, H. Principles of the neutral-zero-passage method. Beitr. Orthop. Traumatol. 1974, 21, 276–285. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J.S.; Kazam, J.J.; Fufa, D.; Bartolotta, R.J. Radiologic evaluation of fracture healing. Skeletal Radiol. 2019, 48, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wunder, J.; Gaul, L.; Gabel, J.; Mestan, A.; von Rüden, C. Modified 3D-Controlled Inside-Out Compression Screw Fixation Technique in Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Narrative Review and Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2026, 15, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010154

Wunder J, Gaul L, Gabel J, Mestan A, von Rüden C. Modified 3D-Controlled Inside-Out Compression Screw Fixation Technique in Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Narrative Review and Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2026; 15(1):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010154

Chicago/Turabian StyleWunder, Johannes, Leander Gaul, Johannes Gabel, Ahmet Mestan, and Christian von Rüden. 2026. "Modified 3D-Controlled Inside-Out Compression Screw Fixation Technique in Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Narrative Review and Case Report" Journal of Clinical Medicine 15, no. 1: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010154

APA StyleWunder, J., Gaul, L., Gabel, J., Mestan, A., & von Rüden, C. (2026). Modified 3D-Controlled Inside-Out Compression Screw Fixation Technique in Posterior Malleolar Fractures: A Narrative Review and Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 15(1), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm15010154