1. Introduction

Heart rhythm disturbances are a common reason for consultation and hospital admission and can be life-threatening. Some people with bradycardia may require temporary pacemaker implantation to ensure a stable rhythm. In temporary pacing, a lead is threaded through a vein to the ventricle to detect the patient’s heart rhythm and, if needed, stimulate myocardial contraction at a determined frequency. This is a common emergency procedure in many critical care units [

1].

The purpose of temporary pacing is to manage symptomatic acute bradycardia, normally caused by degenerative disease of the cardiac conduction system, overdose of negative chronotropic drugs [

2], acute myocardial infarction [

3], conduction abnormalities in people with infective endocarditis [

4], or electrolyte disorders [

5]. Temporary pacing is also commonly used in the perioperative management of people undergoing cardiac surgery, especially valve replacement [

6]. New techniques implemented in the field of interventional cardiology require pre- and post-procedural temporary cardiac pacing. These include transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) and alcohol septal ablation [

7,

8].

Currently, the only certified system for transvenous temporary pacing uses bipolar passive-fixation leads (with no mechanism for active fixation to the myocardium) and a reusable external pulse generator weighing around 800 g. Patients with this type of temporary pacemaker must remain on bed rest with continuous electrocardiographic monitoring. Despite these precautions, complication rates can exceed 35% [

9]. The most common complications are associated with the procedure and include lead displacement resulting in loss of capture and need for repositioning, cardiorespiratory arrest, and heart perforation, sometimes requiring emergency surgery [

10,

11].

Proposed alternatives for reducing the complications and increasing the effectiveness of temporary pacing include the use of bipolar active-fixation leads with a reusable permanent pulse generator [

12]. The latest European Society of Cardiology clinical practice guidelines on cardiac pacing recommend these active-fixation systems for long-term temporary transvenous pacing (class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C) [

13].

This study aimed to evaluate the clinical and economic impact of temporary pacing with active-fixation leads (TPAF) versus temporary pacing with passive-fixation leads (TPPF), to generate evidence on the use of safer and more effective devices for expanding clinical indications.

2. Materials and Methods

Objectives. The main objective of the study was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of off-label active-fixation systems with a reusable permanent pulse generator (TPAF) versus certified conventional transvenous temporary pacemakers with bipolar passive-fixation leads (TPPF). Our secondary objective was to perform an economic analysis of TPAF versus TPPF systems.

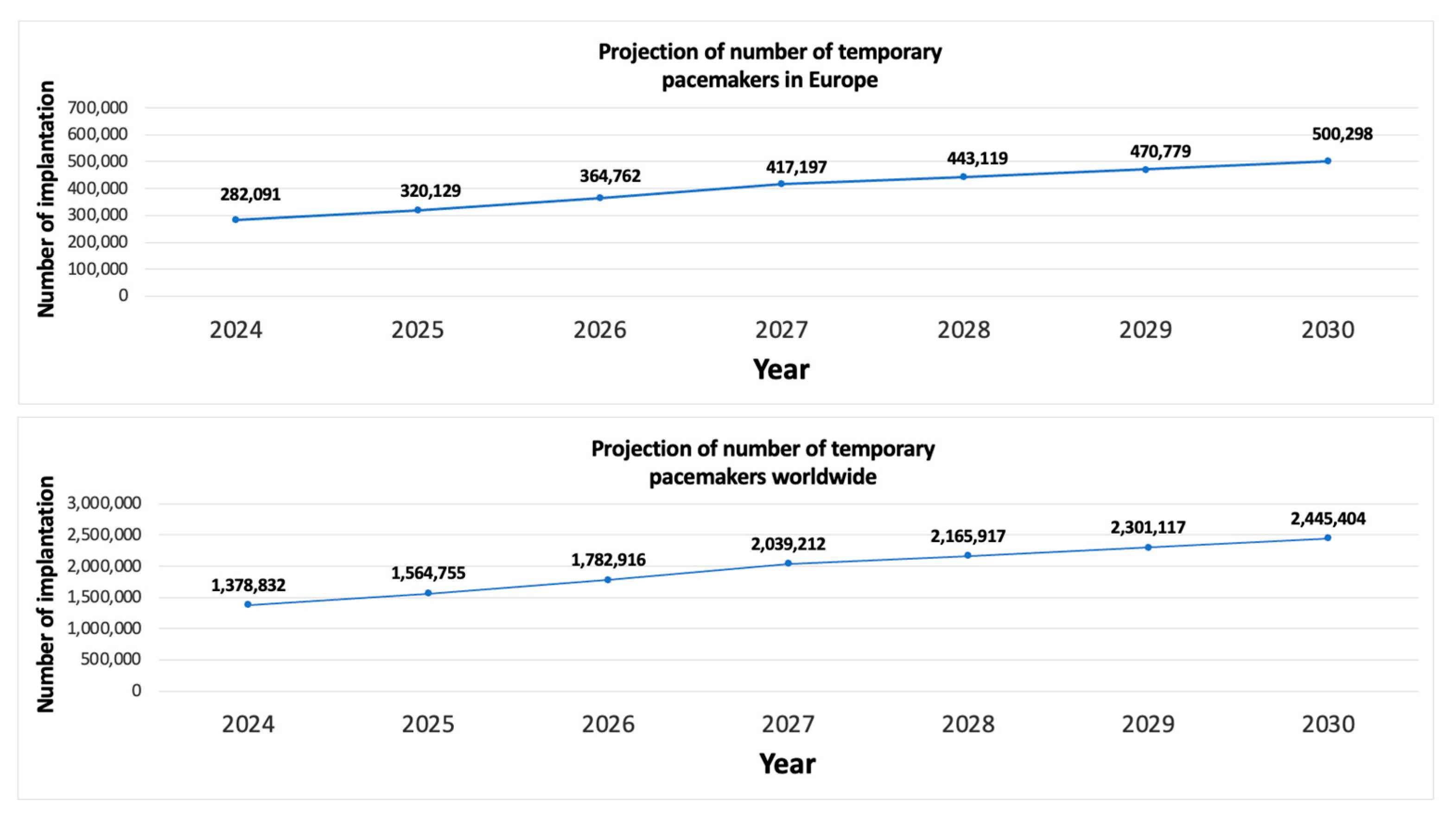

Study design. We designed a descriptive study to evaluate reported complication rates of the two strategies. With the results, we estimated the difference in complications and costs between the two strategies in the Spanish, European, and global context.

To this end, we conducted a bibliographic search in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library for publications related to TPPF and TPAF, using the key words “Temporary Transvenous Cardiac Pacing”, “Cardiac Pacing”, “Temporary Cardiac Stimulation”, “Temporary Pacemaker”, “External Pacemaker”, “Temporary Permanent Pacemaker”, “External Permanent Pacemaker”, “Active-Fixation Temporary Pacemaker”, “Semipermanent Pacemaker”, and “Prolonged Temporary Transvenous Pacemaker”. We reviewed full-text articles published in any language from 1994 (last 30 years) that described complications of TPPF or TPAF in people aged 18 years or older. First, we screened the abstracts and eliminated studies whose objective was unrelated to our primary objective. Next, we reviewed the methods of the remaining studies and discarded studies with a retrospective design. This strict exclusion criteria was necessary because retrospective analyses often rely on clinical records where underreporting of non-major complications (e.g., transient lead displacement or bradycardia) is common. By exclusively focusing on prospective studies designed to record complications, we ensured the complication rates used in our model were based on the most accurate and robust clinical data, despite the resulting low number of included articles (five TPPF and eight TPAF).

For our safety objective, we collected the absolute number and rate of the most frequent temporary pacemaker-related complications: lead displacement, heart perforation/rupture, cardiac tamponade, pericardial effusion, death, bradycardia, ventricular arrhythmias, infection, and non-cardiac hemorrhage. For our effectiveness objective, we collected the number of pacemaker failures. In all cases, we collected the duration of temporary pacing.

For the economic analysis of TPAF versus TPPF, we collected costs associated with the procedures, hospital stays, the medical devices, and treating complications.

We then extrapolated our results to the European Union population and the global population. The global population included the 100 countries with the best healthcare systems according to the Healthcare Access and Quality Index (HAQ Index) [

14], because we only wanted to include countries where temporary pacing is a common procedure. We extracted population data for each country from the public EUROSTAT website [

15].

We analyzed the data using the spreadsheet software Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) then generated tables of the results.

Calculation of economic costs of temporary pacing. Our cost calculation was divided into three general concepts: (1) cost of the temporary pacemaker implantation procedure, including personnel and medical devices; (2) cost of hospital stay; and (3) cost of treating temporary pacemaker-associated complications. We based our estimates on costs published by the Spanish Health System [

16].

Both procedures have similar personnel costs. The cost of medical devices included single-use consumables but not reusable generators, which are used in multiple patients and thus have a negligible per-patient cost. To calculate the cost of hospital stays, we used an average temporary pacing duration of seven days, based on publications about active-fixation systems in the general population [

12,

17]. Studies of TPAF do not limit the duration of therapy due to lack of safety or effectiveness: the device remains in place for the time needed to make decisions. People with TPPF have to stay in the critical care unit throughout therapy, whereas we counted only one day in the critical care unit for people with TPAF, followed by six days in a ward with telemetry.

4. Discussion

Numerous publications have shown that temporary pacing systems with active-fixation leads are sufficiently safe and effective for use outside the critical care unit [

12,

17,

23], and favorable results have even been reported outside the hospital setting [

30]. The average duration of cardiac pacing varies considerably between studies on TPPF (3.7 days) and TPAF (11.8 days), mainly because of differences in the indication for pacing. Studies of TPAF have included people who needed a longer duration of pacing, for reasons such as permanent pacemaker-associated infection. In contrast, because of the high frequency of associated complications [

10,

11], and the need for patients to stay in the critical care unit, clinicians are more likely to remove TPPF systems early, often too early.

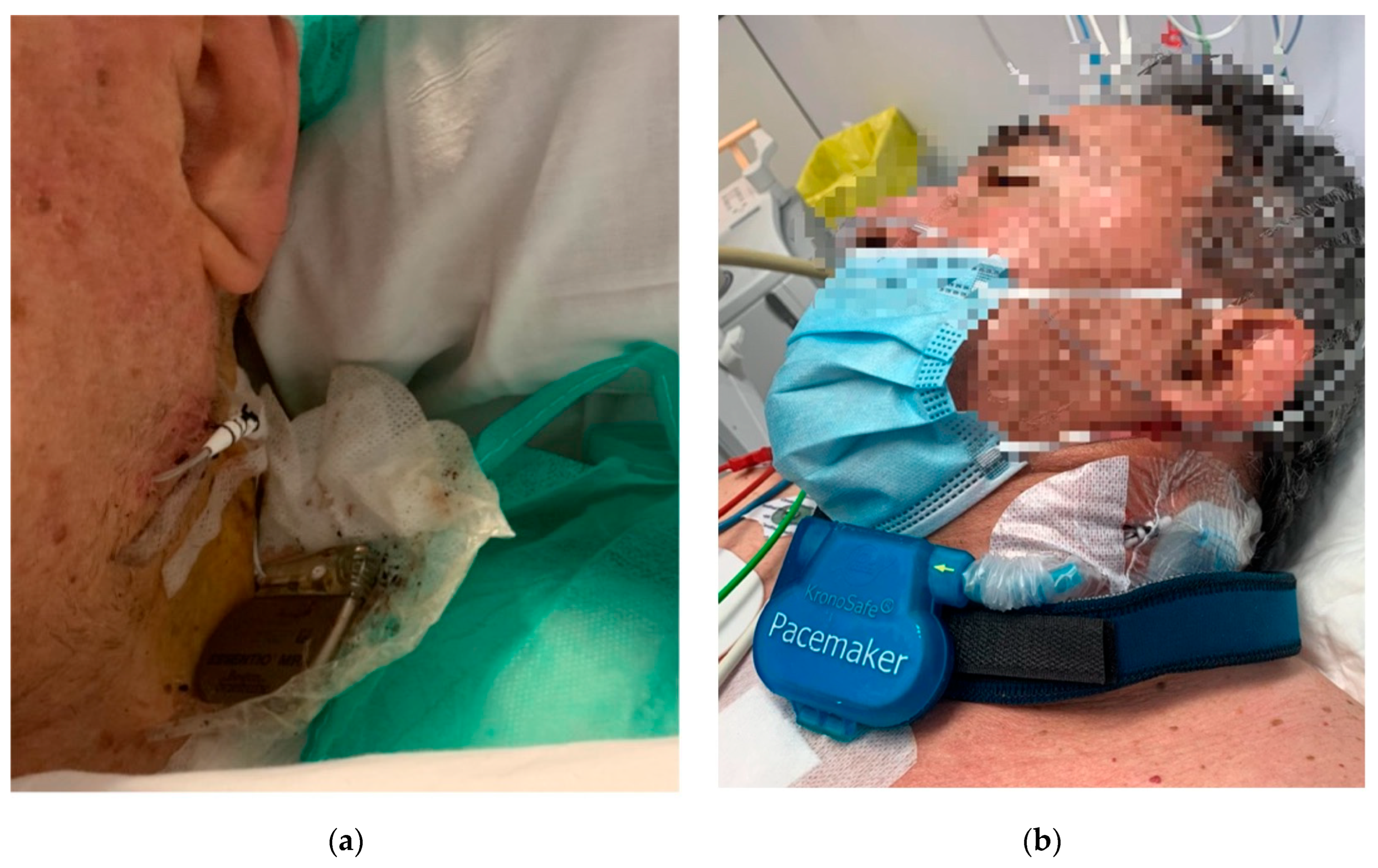

One of the limitations of TPAF is the lack of certified devices specifically designed for this purpose. The off-label use of permanent pacemakers externalized for temporary cardiac pacing has improved clinical results and recently the European Society of Cardiology recommends these systems in their last cardiac stimulation guidelines [

13]. However, there are still risks for the patient, such as intravascular infection or accidental detachment of the generator (

Figure 3a). Solutions such as specialized external fastening systems could address the risk of accidental detachment associated with externalized permanent pacemakers (

Figure 3b) [

12].

Because TPAF systems are safe and effective, the duration of temporary pacing can be extended to better suit the needs of the patient and the healthcare system. Kordoni and colleagues reported optimal functional outcomes in a patient with autonomic dysfunction secondary to Miller-Fisher syndrome who was treated with TPAF for five weeks [

31]. With TPAF systems, clinicians have more time for clinical decision-making and can avoid unnecessary permanent pacemaker implantations. Henry D and colleagues recognize that external pressure on clinicians to reduce the length of hospital stays and mobilize patients early after TAVI may lead to unnecessary indications for permanent pacemaker implantation [

32]. Reported rates of atrioventricular conduction recovery after TAVI are as high as 50%. Including active-fixation systems to assist the TAVI procedure and maintain the temporary pacemaker during the patient’s hospital stay (median of seven days) [

33] could optimize decision-making.

As with any external device, there is a risk of accidental pulling and detachment of the system, which would put the patient’s life at risk in this case. External fastening solutions could help standardize the use of this material, potentially increasing treatment safety [

12].

Regarding the economic impact of TPAF, we estimated considerable savings for healthcare systems owing to the lower cost of hospital stays in the cardiology ward versus the critical care unit (

Table 6). In addition, providing temporary pacing in a ward reduces the caseload of high-complexity units. Lastly, because patients on TPAF systems can receive temporary pacing for longer, clinicians can optimize indications for permanent pacemaker implantation, possibly reducing the number of unnecessary procedures. The cost of the implantation, follow-up, and management of complications over the first year can be up to EUR 7000, then EUR 500 per year for the remainder of treatment [

16,

34].

The costs associated with temporary pacing vary across countries and healthcare systems. Nonetheless, we estimated that the use of active-fixation systems could reduce the overall cost of temporary pacing by 55%, mainly owing to the reduced cost of hospital stays and treatment of complications.

The excellent clinical results published to date with active fixation leads and their expected associated economic benefits were not reflected in real practice with The Tempo Lead (Merit Medical Systems Inc., 1600 Wert Merit Parkway, South Jordan 84095, UT, USA) [

35]. The lack of clinician adoption led to the discontinuation of the distally stabilized lead. Not only all of these aspects represent a comparative benefit of TPAF but also, the possibility of performing temporary cardiac stimulation at home when used with a secure external fixation system. Out-of-hospital temporary cardiac stimulation would allow for an increased duration of patient’s heart rhythm evaluation and to more accurately determine the need for a permanent pacemaker.

Our study has some limitations, such as its descriptive design, the substantial variability between the reported clinical results of TPPF (possibly depending on each center’s experience with this treatment), the scarcity of prospective studies comparing the two systems (TPPF vs. TPAF), the age of the studies (most from the 2000s), and possible nonpublication of studies with unfavorable results (publication bias). A significant limitation of our economic analysis is the extrapolation of costs. The cost figures for personnel, hospital stays, and complication treatments were sourced exclusively from the Spanish Health System. While this allowed for a direct comparative assessment, we acknowledge that healthcare costs and resource allocation vary considerably across European and global populations. Therefore, the financial savings estimated in

Table 5 and

Table 6 should be interpreted as theoretical projections and indicators of magnitude, rather than precise costs applicable to all healthcare environments globally.

The duration of temporary cardiac pacing between the TPPF and TPAF groups also differed significantly. This may be primarily due to the difference in the indication for pacing and the need to make hasty decisions in the TPPF group due to its lack of safety. We do not consider that this difference does not allow us to compare both procedures, and furthermore, despite the longer times in the TPAF group, the safety and effectiveness results are better.