The Role of Prophylactic Gastrectomy in Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

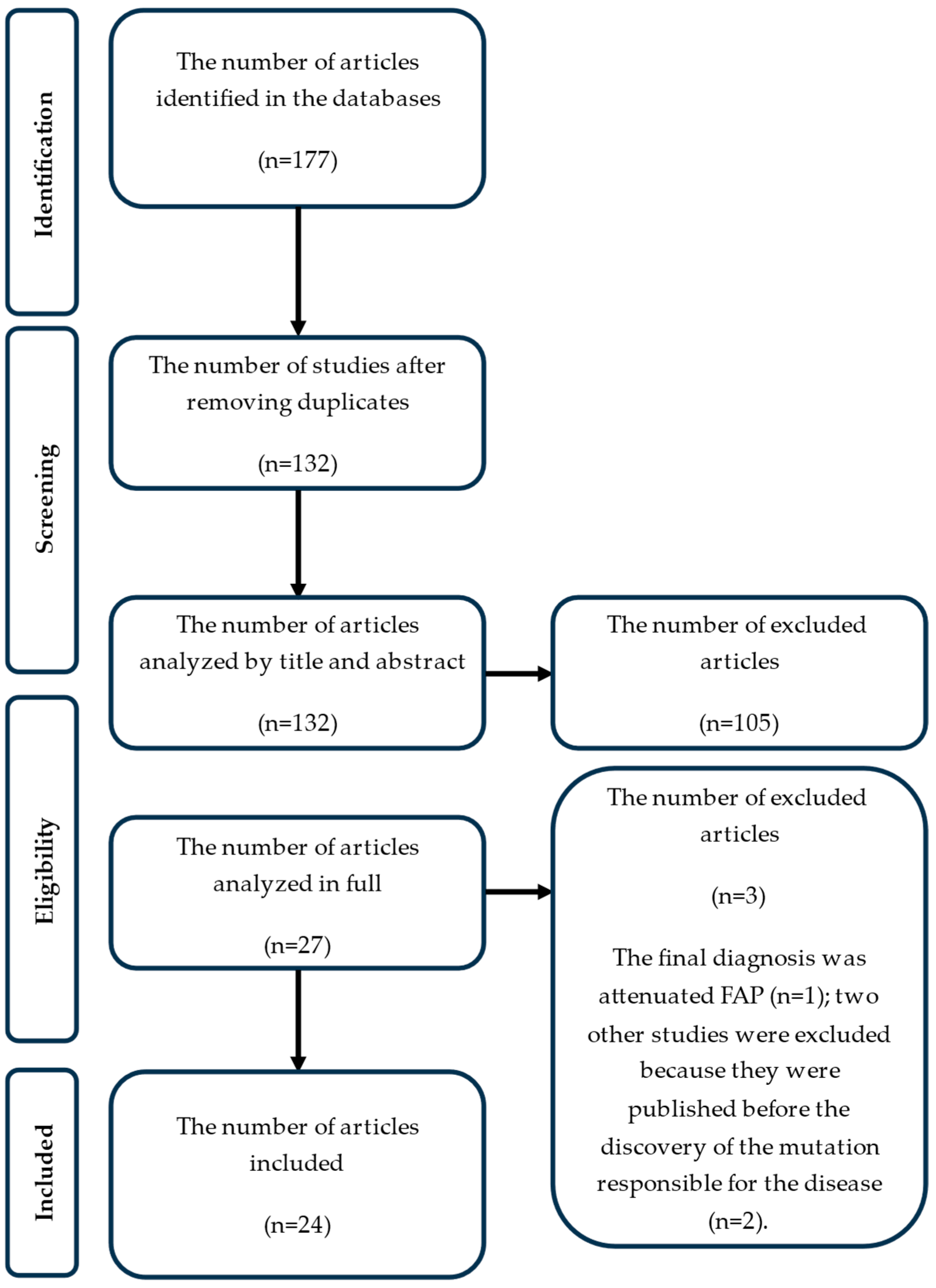

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Search Strategies

2.3. Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion

- Studies that included patients diagnosed with GAPPS who benefited from prophylactic gastrectomy and patients who did not benefit from this intervention. From the second category, we have patients with endoscopic follow-up, therapeutic gastrectomy, or patients with advanced gastric cancer and GAPPS who benefited only from chemotherapy regardless of their age;

- Original research articles and reviews, case reports, conference abstracts, and images;

- The language of the study’s publication, which was not to be a reason for exclusion.

- Studies in which the diagnosis of GAPPS is not specified;

- Studies that included patients who underwent prophylactic gastrectomy due to the increased risk of HDGC or FIGC;

- Studies that included patients with prophylactic gastrectomy performed due to the increased risk of gastric cancer within other familial cancer syndromes, such as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC)-Lynch syndrome; Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS); FAP; and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

2.4. Data Extraction, Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

- One study because the final diagnosis was attenuated FAP (n = 1);

- Two other studies because they were published before the discovery of the mutation responsible for the disease (n = 2),

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies and Demographic Data of the Enrolled Patients

3.2. Clinical-Diagnostic Aspects of the Enrolled Patients

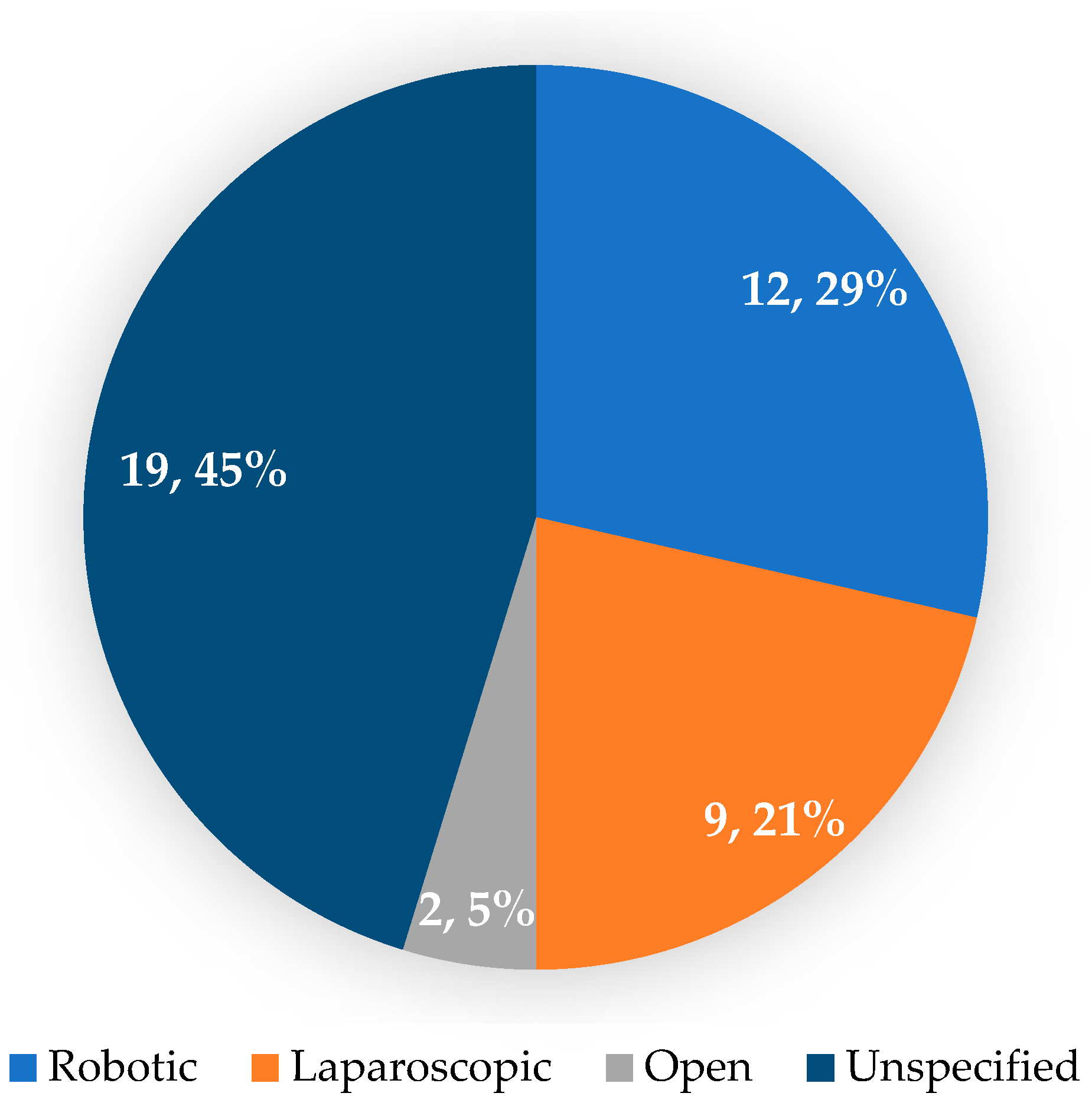

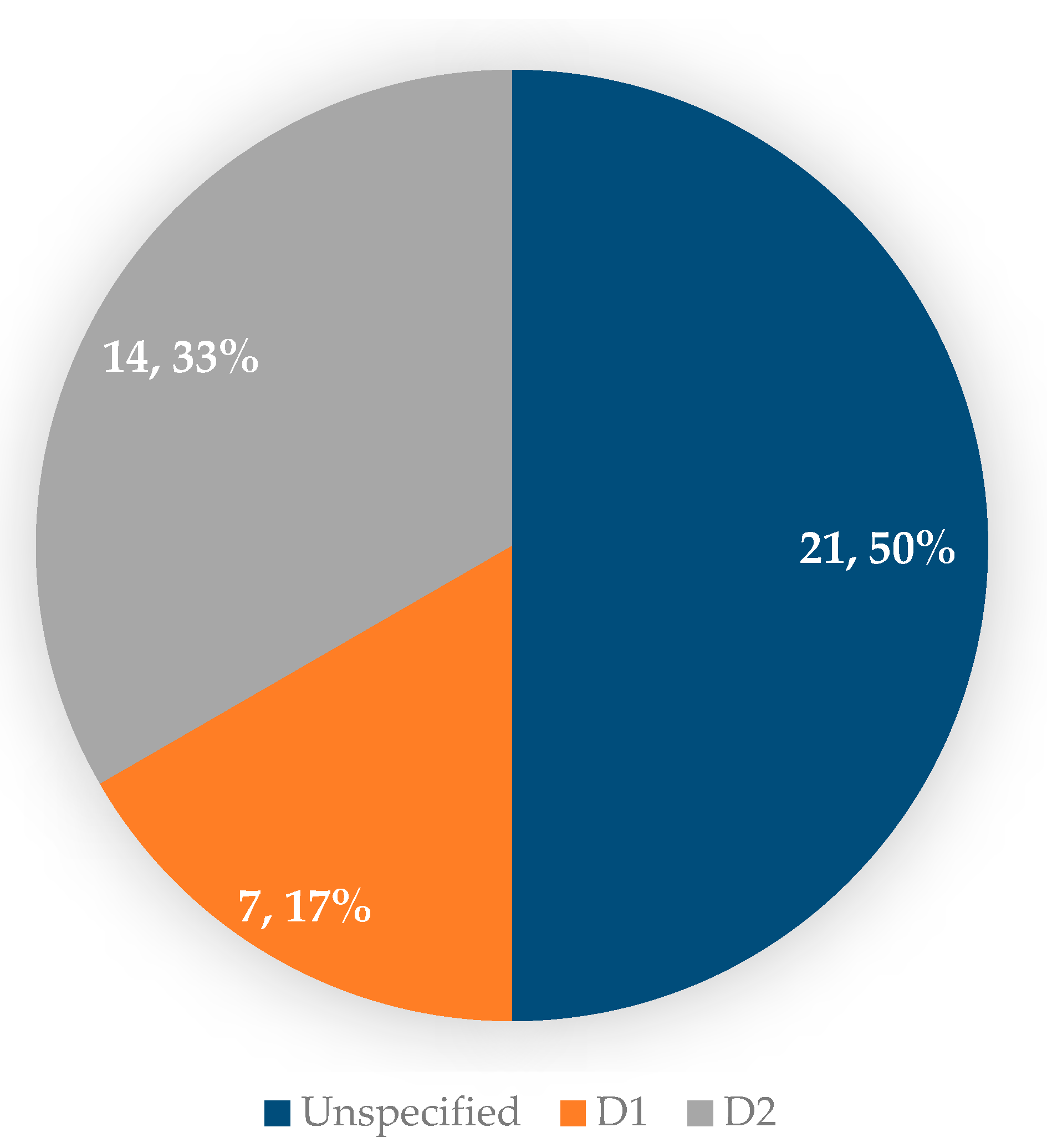

3.3. Operative and Postoperative Aspects of Patients with GAPPS Who Underwent Prophylactic Gastrectomy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karimi, P.; Islami, F.; Anandasabapathy, S.; Freedman, N.D.; Kamangar, F. Gastric Cancer: Descriptive Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Screening, and Prevention. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 700–713. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, V.R.; McLeod, M.; Carneiro, F.; Coit, D.G.; D’Addario, J.L.; Van Dieren, J.M.; Harris, K.L.; Hoogerbrugge, N.; Oliveira, C.; Van Der Post, R.S.; et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: Updated clinical practice guidelines. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e386–e397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, F. Familial and hereditary gastric cancer, an overview. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2022, 58–59, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarvand, P.; Davaro, E.P.; Doan, J.V.; Ising, M.E.; Evans, N.R.; Phillips, N.J.; Lai, J.; Guzman, M.A. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Syndrome: An Update and Review of Extraintestinal Manifestations. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2019, 143, 1382–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Worthley, D.L.; Phillips, K.D.; Wayte, N.; Schrader, K.A.; Healey, S.; Kaurah, P.; Shulkes, A.; Grimpen, F.; Clouston, A.; Moore, D.; et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS): A new autosomal dominant syndrome. Gut 2012, 61, 774–779, Erratum in Gut 2012, 61, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacheci, I.; Repak, R.; Podhola, M.; Benesova, L.; Cyrany, J.; Bures, J.; Kohoutova, D. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS)—A Helicobacter-opposite point. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 50, 101728. [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsuki, M.; Matsumoto, C.; Mimori, K.; Baba, H. The comprehensive review of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS) from diagnosis and treatment. Ann. Gastroenterol. Surg. 2023, 7, 725–732. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Woods, S.L.; Healey, S.; Beesley, J.; Chen, X.; Lee, J.S.; Sivakumaran, H.; Wayte, N.; Nones, K.; Waterfall, J.J.; et al. Point Mutations in Exon 1B of APC Reveal Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach as a Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Variant. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 830–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.G.; Bujarska, M.; Bauer, M.; Brathwaite, C.; Pelaez, L.; Reeves-Garcia, J. Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach in a Hispanic Pediatric Patient with APC Gene Variant c.-191T>G. JPGN Rep. 2021, 2, e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, A.; Inokuchi, Y.; Hirata, M.; Narimatsu, H.; Yoshioka, E.; Washimi, K.; Machida, N.; Maeda, S. A case of an unreported point mutation in promoter 1B of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene, which is responsible for gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 17, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salami, A.C.; Stone, J.M.; Greenberg, R.H.; Leighton, J.C.; Miick, R.; Zavala, S.R.; Zeitzer, K.L.; Bakhos, C.T. Early Prophylactic Gastrectomy for the Management of Gastric Adenomatous Proximal Polyposis Syndrome (GAPPS). ACS Case Rev. Surg. 2022, 3, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Repak, R.; Kohoutova, D.; Podhola, M.; Rejchrt, S.; Minarik, M.; Benesova, L.; Lesko, M.; Bures, J. The first European family with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach: Case report and review of the literature. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 84, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, A.; Streubel, B.; Asari, R.; Dejaco, C.; Oberhuber, G. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS)—A rare recently described gastric polyposis syndrome—Report of a case. Z. Für Gastroenterol. 2017, 55, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, M.; Otsuka, K.; Aoki, H.; Teramae, S.; Omoya, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakamato, J.; Shibata, H.; Yagi, T.; Kudo, E. A case of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach. J. Jpn. Soc. Gastroenterol. Endosc. 2018, 60, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui, Y.; Yokoyama, R.; Fujimoto, S.; Kagemoto, K.; Kitamura, S.; Okamoto, K.; Muguruma, N.; Bando, Y.; Eguchi, H.; Okazaki, Y.; et al. First report of an Asian family with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS) revealed with the germline mutation of the APC exon 1B promoter region. Gastric Cancer 2018, 21, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretova, L.; Navratilova, M.; Svoboda, M.; Grell, P.; Nemec, L.; Sirotek, L.; Obermannova, R.; Novotny, I.; Sachlova, M.; Fabian, P.; et al. GAPPS—Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach Syndrome in 8 Families Tested at Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute—Prevention and Prophylactic Gastrectomies. Klin. Onkol. 2019, 32 (Suppl. S2), 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovsky, L.; Kala, Z.; Potrusil, M.; Novotny, I.; Kubes, V.; Prochazka, V. A Central European family with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2019, 90, 523–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; Swanson, L.; Plummer, R.; Abraham, J. Identifying the GAPPS in Hereditary Gastric Polyposis Syndromes: 2707. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, S1510–S1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mala, T.; Førland, D.T.; Vetti, H.H.; Skagemo, C.U.; Johannessen, H.O.; Johnson, E. Gastrisk adenokarsinom og proksimal ventrikkelpolypose—En sjelden form for arvelig magesekkreft [Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach—A rare form of hereditary gastric cancer]. Tidsskr. Den Nor. Legeforening 2020, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanemitsu, K.; Iwatsuki, M.; Yamashita, K.; Komohara, Y.; Morinaga, T.; Iwagami, S.; Eto, K.; Nagai, Y.; Kurashige, J.; Baba, Y.; et al. Two Asian families with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach successfully treated via laparoscopic total gastrectomy. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 14, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ako, S.; Kawano, S.; Okada, H. Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach Occurring with Ball Valve Syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 20, e12–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, C.; Iwatsuki, M.; Iwagami, S.; Morinaga, T.; Yamashita, K.; Nakamura, K.; Eto, K.; Kurashige, J.; Baba, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; et al. Prophylactic laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS): The first report in Asia. Gastric Cancer 2021, 25, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, A.; Colavito, J.; Levine, J.; Thomas, K.M.; Greifer, M. Filling in the “GAPPS”: An unusual presentation of a child with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach. Gastric Cancer 2021, 25, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Powers, J.; Sande, C.M.; Fortuna, D.; Katona, B.W. Multifocal Intramucosal Gastric Adenocarcinoma Arising in Fundic Gland Polyposis Due to Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 116, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Iwakawa, Y.; Yoshikawa, K.; Okamoto, K.; Takayama, T.; Tokunaga, T.; Nakao, T.; Nishi, M.; Takasu, C.; Kashihara, H.; Wada, Y.; et al. Four cases of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach treated by robotic total gastrectomy. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mala, T.; Førland, D.; Skagemo, C.; Glomsaker, T.; Johannessen, H.O.; Johnson, E. Early experience with total robotic D2 gastrectomy in a low incidence region: Surgical perspectives. BMC Surg. 2022, 22, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, T.; Sera, T.; Aoyama, R.; Sawada, A.; Kasashima, H.; Ogisawa, K.; Bamba, H.; Yashiro, M. Two families with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS): Case reports and literature review. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2023, 14, 2650–2657. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Y.; Kusuhara, M.; Ohno, A.; Miyamoto, N.; Hada, Y.; Shibahara, J.; Hisamatsu, T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for adenoma in gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach. Endoscopy 2023, 55 (Suppl. S1), E928–E929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamuro, M.; Kawano, S.; Otsuka, M. An Unusual Case of Gastric Polyposis. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 1110–1113. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kagemoto, K.; Kida, Y.; Mitsui, Y.; Nakamura, F.; Yoshikawa, K.; Sogabe, M.; Sato, Y.; Shunto, J.; et al. Gastric fundic gland polyposis and cancer development after eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patient with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS). Gastric Cancer 2024, 27, 635–640. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, R.; Kawano, S.; Iwamuro, M.; Tanaka, T.; Otsuka, M. Familial Case of Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach: A Long-Term Endoscopic Observation. Ann. Intern. Med. Clin. Cases 2024, 3, e231431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, S.J.; Gearty, S.V.; Catchings, A.; Ranganathan, M.; Roehrl, M.H.; Vardhana, S.A.; Tang, L.; Stadler, Z.K.; Strong, V.E. Consideration of a Novel Surgical Approach in the Management of Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis Syndrome. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, e2400175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witt, L.; Pillay, Y.; Sabaratnam, R.M.; Bigsby, R.J. De novo adolescent gastric carcinoma: A first case report in Saskatchewan, Canada. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 2020, rjaa249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessler, R.A.; Dellinger, M.; Richards, M.K.; Goldin, A.B.; Beierle, E.A.; Doski, J.J.; Goldfarb, M.; Langer, M.; Nuchtern, J.G.; Raval, M.V.; et al. Pediatric gastric adenocarcinoma: A National Cancer Data Base review. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel-Nunes, P.; Libânio, D.; Marcos-Pinto, R.; Areia, M.; Leja, M.; Esposito, G.; Garrido, M.; Kikuste, I.; Megraud, F.; Matysiak-Budnik, T.; et al. Management of epithelial precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS II): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group (EHMSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED) guideline update 2019. Endoscopy 2019, 51, 365–388. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, B.; Borogovac, A.; Churrango, G.; Zivny, J. A Carpet of Polyps: Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach (GAPPS): 2538. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, S1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, B.F.; Hernandez, J.M.; Quezado, M.; Heller, T.; Koh, C.; Davis, J.L. 94—Systematic Screening Protocol for the Stomach (SSP) is Superior to Standard Endoscopy for the Detection of Early Malignancy in Hereditary Gastric Cancer Syndrome Patients. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, S-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K. The endoscopic diagnosis of early gastric cancer. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2013, 26, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Klang, E.; Soroush, A.; Nadkarni, G.; Sharif, K.; Lahat, A. Deep Learning and Gastric Cancer: Systematic Review of AI-Assisted Endoscopy. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Overview on Techniques, Taxonomy, Applications and Research Directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.d.M.; Poly, T.N.; Walther, B.A.; Lin, M.-C.; Li, Y.-C. Artificial Intelligence in Gastric Cancer: Identifying Gastric Cancer Using Endoscopic Images with Convolutional Neural Network. Cancers 2021, 13, 5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conte, L.; Rizzo, E.; Grassi, T.; Bagordo, F.; De Matteis, E.; De Nunzio, G. Artificial Intelligence Techniques and Pedigree Charts in Oncogenetics: Towards an Experimental Multioutput Software System for Digitization and Risk Prediction. Computation 2024, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, N.; Lawton, J.; Badger, S.; Richardson, S.; Hardwick, R.H.; Caldas, C.; Fitzgerald, R.C. The Psychosocial Impact of Undergoing Prophylactic Total Gastrectomy (PTG) to Manage the Risk of Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer (HDGC). J. Genet. Couns. 2016, 26, 752–762. [Google Scholar]

- Stillman, M.D.; Kusche, N.; Toledano, S.; Hilfrank, K.J.; Yoon, C.; Gabre, J.T.; Rustgi, S.D.; Hur, C.; Kastrinos, F.; Ryeom, S.W.; et al. Short and long-term outcomes of prophylactic total gastrectomy in 54 consecutive individuals with germline pathogenic mutations in the CDH1 gene. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 126, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Kaaij, R.T.; Van Kessel, J.P.; Van Dieren, J.M.; Snaebjornsson, P.; Balagué, O.; Van Coevorden, F.; Van Der Kolk, L.E.; Sikorska, K.; Cats, A.; Van Sandick, J.W. Outcomes after prophylactic gastrectomy for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, e176–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaffaroni, G.; Mannucci, A.; Koskenvuo, L.; De Lacy, B.; Maffioli, A.; Bisseling, T.; Half, E.; Cavestro, G.M.; Valle, L.; Ryan, N.; et al. Updated European guidelines for clinical management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP), gastric adenocarcinoma, proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS) and other rare adenomatous polyposis syndromes: A joint EHTG-ESCP revision. Br. J. Surg. 2024, 111, znae070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Skat-Rørdam, P.A.; Kaya, Y.; Qvist, N.; Hansen, T.; Jensen, T.D.; Karstensen, J.G.; Jelsig, A.M. Gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS): A systematic review with analysis of individual patient data. Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract. 2024, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Chen, L.; Liao, M.; Chen, B.; Long, J.; Wu, W.; Deng, G. Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 978–989. [Google Scholar]

- Mala, T.; Johannessen, H.-O.; Førland, D.; Jacobsen, T.H.; Johnson, E. Laparoskopisk reseksjon av ventrikkelcancer ved Oslo universitetssykehus, Ullevål 2015–2018 [Laparascopic resection for gastric cancer at Oslo University Hospital, Ullevål 2015–2018]. Tidsskr. Den Nor. Legeforen. 2018, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-B.; Wang, W.-J.; Li, H.-T.; Han, X.-P.; Su, L.; Wei, D.-W.; Cao, T.-B.; Yu, J.-P.; Jiao, Z.-Y. Robotic versus conventional laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 55, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hikage, M.; Fujiya, K.; Kamiya, S.; Tanizawa, Y.; Bando, E.; Terashima, M. Comparisons of surgical outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic total gastrectomy in patients with clinical stage I/IIA gastric cancer. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 5257–5266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaurah, P.; Fitzgerald, R.; Dwerryhouse, S.; Huntsman, D.G. Pregnancy after prophylactic total gastrectomy. Fam. Cancer 2010, 9, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ueda, H.; Mitsui, Y.; Takishita, M.; Yano, M.; Takehara, M.; Fukuya, A.; Kawaguchi, T.; Noda, K.; Kitamura, S.; Okamoto, K.; et al. Tu1221 Clinicopathological Analysis of Six Families with Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach (GAPPS). Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 447–459. [Google Scholar]

- Malfertheiner, P.; Kandulski, A.; Venerito, M. Proton-pump inhibitors: Understanding the complications and risks. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossmark, R.; Jianu, C.S.; Martinsen, T.C.; Qvigstad, G.; Syversen, U.; Waldum, H.L. Serum gastrin and chromogranin A levels in patients with fundic gland polyps caused by long-term proton-pump inhibition. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 43, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, N.; Seno, H.; Nakajima, T.; Yazumi, S.; Miyamoto, S.; Matsumoto, S.; Itoh, T.; Kawanami, C.; Okazaki, K.; Chiba, T. Regression of fundic gland polyps following acquisition of Helicobacter pylori. Gut 2002, 51, 742–745. [Google Scholar]

- Okano, A.; Takakuwa, H.; Matsubayashi, Y. DEVELOPMENT OF SPORADIC GASTRIC FUNDIC GLAND POLYP AFTER ERADICATION OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI. Dig. Endosc. 2007, 20, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rudloff, U. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach: Diagnosis and clinical perspectives. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 447–459. [Google Scholar]

- McDuffie, L.A.; Sabesan, A.; Allgäeuer, M.; Xin, L.; Koh, C.; Heller, T.; Davis, J.L.; Raffeld, M.; Miettienen, M.; Quezado, M.; et al. β-Catenin activation in fundic gland polyps, gastric cancer and colonic polyps in families afflicted by ‘gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach’ (GAPPS). J. Clin. Pathol. 2016, 69, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, W.B.; Ee, H.; Kumarasinghe, M.P. Neoplastic lesions of gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis syndrome (GAPPS) are gastric phenotype. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Endoscopic identification of numerous polyps located in the gastric fundus and body, excluding the presence of duodenal and colorectal polyps [5] | Patient with gastric polyps with long-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors—it is recommended to repeat the endoscopy after discontinuing the treatment [5] |

| Very large number of polyps, over 100, or over 30 polyps in the case of a close relative of another case [5] | Patient with other criteria that allow the diagnosis of hereditary gastric polyposis within other diseases [5] |

| Polypi located at the level of the gastric fundus presenting dysplasia [5] | |

| A family member diagnosed with gastric fundic polyposis or gastric adenocarcinoma [5] | |

| Demonstration of autosomal dominant genetic transmission [5] |

| First Author Name and References (REF) | Study Design | Year of Publication of the Study | The Place Where the Study Was Conducted | The Number of Patients Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repak, R. et al. [12] | case report and review | 2016 | Europe—Czech Republic | 4 |

| Beer, A. et al. [13] | case report | 2017 | Europe—Austria | 1 |

| Yano, M. et al. [14] | case report | 2018 | Asia—Japan | 1 |

| Mitsui, Y.et al. [15] | case report | 2018 | Asia—Japan | 3 |

| Foretova, L. et al. [16] | original article | 2019 | Europe—Czech Republic | 24 |

| Kunovsky, L. et al. [17] | case report | 2019 | Europe—Czech Republic | 2 |

| Anderson, A. et al. [18] | case report | 2019 | USA—Minnesota | 1 |

| Mala, T. et al. [19] | case report and review | 2020 | Europe—Norway | 5 |

| Kanemitsu, K. et al. [20] | case report | 2020 | Asia—Japan | 4 |

| Ako, S. et al. [21] | image | 2020 | Asia—Japan | 3 |

| Matsumoto, C. et al. [22] | case report | 2021 | Asia—Japan | 3 |

| Roberts, A.G. et al. [9] | case report | 2021 | USA—Florida | 1 |

| Grossman, A. et al. [23] | case report | 2021 | USA—NY | 1 |

| Powers, J. et al. [24] | image | 2021 | USA—Pennsylvania | 1 |

| Salami, A.C. et al. [11] | case series and review | 2022 | USA—Philadelphia | 2 |

| Iwakawa, Y. et al. [25] | case report | 2022 | Asia—Japan | 4 |

| Mala, T. et al. [26] | research article | 2022 | Europe—Norway | 8 |

| Sakuma, T. et al. [27] | case report and review | 2023 | Asia—Japan | 6 |

| Saito, Y. et al. [28] | e-videos | 2023 | Asia—Japan | 1 |

| Iwamuro, M.et al. [29] | case report | 2023 | Asia—Japan | 3 |

| Okamoto, K. et al. [30] | case report | 2024 | Asia—Japan | 2 |

| Hirai, R. et al. [31] | case report | 2024 | Asia—Japan | 1 (3 cases presented, also appear in Ako, S.) |

| Ishida, A. et al. [10] | case report | 2024 | Asia—Japan | 1 |

| Judge, S.J. et al. [32] | case report | 2024 | USA—California | 1 |

| Patients with Prophylactic Gastrectomy | Patients Without Prophylactic Gastrectomy | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with Therapeutic Gastrectomy | Patients with Endoscopic Follow-Up | Patients with Gastric Cancer Receiving Only Oncological Treatment | |||

| Patients diagnosed with GAPPS | 42 (50.60%) | 8 (9.63%) | 24 (28.91%) | 9 (10.84%) | 83 (100%) |

| Patients average age (years) | 42 years (8–71 years) | 43.1 years (24–69 years) | 45.3 years (22–92 years) | 45.5 years (26–64 years) | 43 years |

| Gender | |||||

| F | 17 (40.47%) | 7 (87.50%) | 18 (75%) | 7 (77.77%) | 49 (59.03%) |

| M | 12 (28.57%) | 1 (12.50%) | 6 (25%) | 2 (22.27%) | 21 (25.30%) |

| Unspecified | 13 (30.95%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (15.66%) |

| EGD | |||||

| YES polyps | 34 (80.95%) | 8 (100%) | 19 (79.16%) | 9 (100%) | 70 (84.33%) |

| Normal | 0(0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (12.50%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3.61%) |

| NOT performed | 0(0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.16%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.20%) |

| Unspecified | 8 (19.04%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.16%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (10.84%) |

| Colonoscopy | |||||

| Normal appearance | 9 (21.42%) | 6 (75%) | 1 (4.16%) | 1 (11.11%) | 17 (20.48%) |

| Presence of polyps | 8 (19.04%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (22.22%) | 11 (13.25%) |

| Unspecified | 24 (57.14%) | 1 (12.5%) | 23 (95.83%) | 5 (55.55%) | 53 (63.85%) |

| NOT performed | 0(0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11.11%) | 1 (1.20%) |

| Other pathologies | 1 (2.38%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.20%) |

| PPI treatment | |||||

| YES | 7 (16.66%) | 2 (25%) | 2 (8.33%) | 2 (22.22%) | 13 (15.66%) |

| NO | 8 (19.04%) | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (12.50%) | 7 (77.77%) | 23 (27.71%) |

| Unspecified | 27 (64.28%) | 1 (12.5%) | 19 (79.16%) | 0 (0%) | 47 (56.62%) |

| HP infection | |||||

| YES | 0 (0%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (4.16%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3.61%) |

| NO | 7 (16.66%) | 6 (75%) | 5 (20.83%) | 2 (22.22%) | 20 (24.09%) |

| Unspecified | 35 (83.33%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (75%) | 7 (77.77%) | 60 (72.28%) |

| Genetic mutation | |||||

| c. 191 T > C | 14 (33.33%) | 6 (75%) | 16 (66.66%) | 7 (77.77%) | 43 (51.80%) |

| c. 191 T > G | 1 (2.38%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.40%) |

| c. 195 A > C | 1 (2.38%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.20%) |

| c. 195 A > G | 3 (7.14%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (12.5%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (7.22%) |

| c. −30,217 T > C | 1 (2.38%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.20%) |

| non-specific | 22 (52.38%) | 1 (12.5%) | 5 (20.83%) | 2 (22.22%) | 30 (36.14%) |

| Imagistics CT | |||||

| Normal | 6 (14.28%) | 8 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (16.86%) |

| Pathologic | 1 (2.38%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (33.33%) | 4 (4.81%) |

| Unspecified | 35 (83.33%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (100%) | 6 (66.66%) | 65 (78.31%) |

| Esophagogastroduodenoscopy | Prophylactic Gastrectomy | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

| Disadvantages |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fugărețu, C.; Șurlin, V.M.; Misarca, C.; Marinescu, D.; Patrascu, S.; Ramboiu, S.; Petre, R.; Strâmbu, V.D.E.; Schenker, M. The Role of Prophylactic Gastrectomy in Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072522

Fugărețu C, Șurlin VM, Misarca C, Marinescu D, Patrascu S, Ramboiu S, Petre R, Strâmbu VDE, Schenker M. The Role of Prophylactic Gastrectomy in Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(7):2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072522

Chicago/Turabian StyleFugărețu, Cosmina, Valeriu Marin Șurlin, Catalin Misarca, Daniela Marinescu, Stefan Patrascu, Sandu Ramboiu, Radu Petre, Victor Dan Eugen Strâmbu, and Michael Schenker. 2025. "The Role of Prophylactic Gastrectomy in Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 7: 2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072522

APA StyleFugărețu, C., Șurlin, V. M., Misarca, C., Marinescu, D., Patrascu, S., Ramboiu, S., Petre, R., Strâmbu, V. D. E., & Schenker, M. (2025). The Role of Prophylactic Gastrectomy in Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Proximal Polyposis of the Stomach: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(7), 2522. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072522