Advanced Diagnostic Methods in Necrotizing Sialometaplasia of the Parotid Glands: An Updated Literature Review and a Rare Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

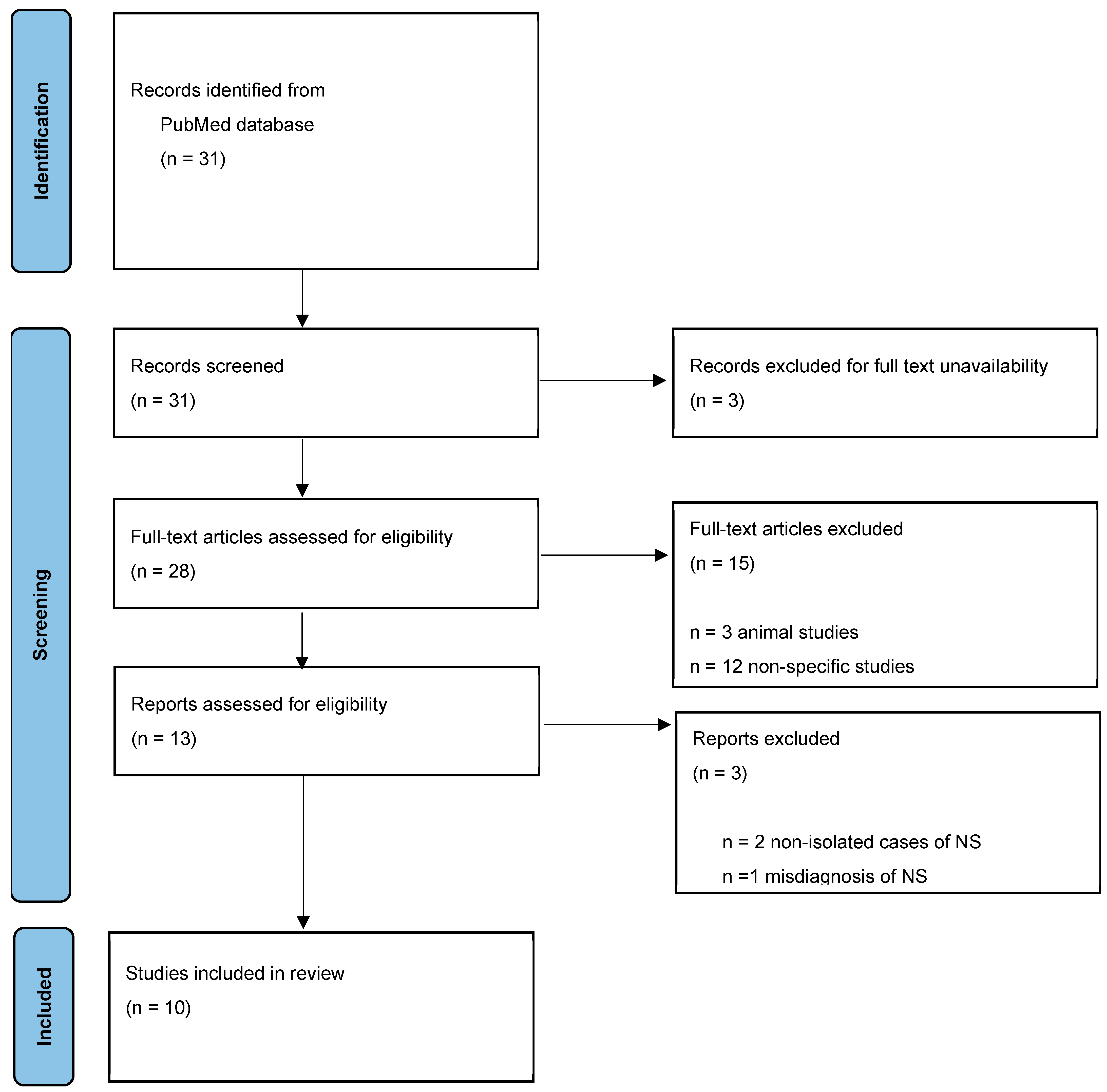

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology

3.2. Etiology

3.3. Clinical Features

3.4. Diagnosis

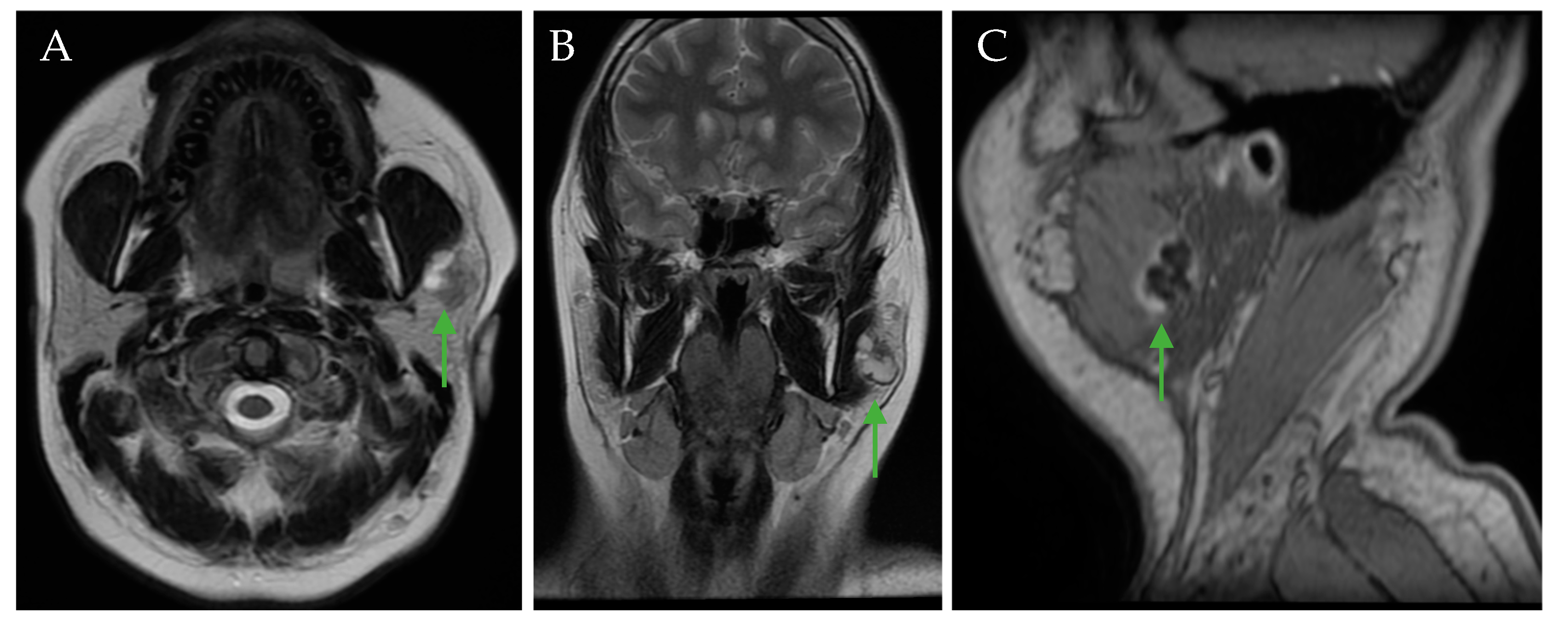

3.5. Radiology Assessment

3.6. Reports of Cases

3.7. Treatment

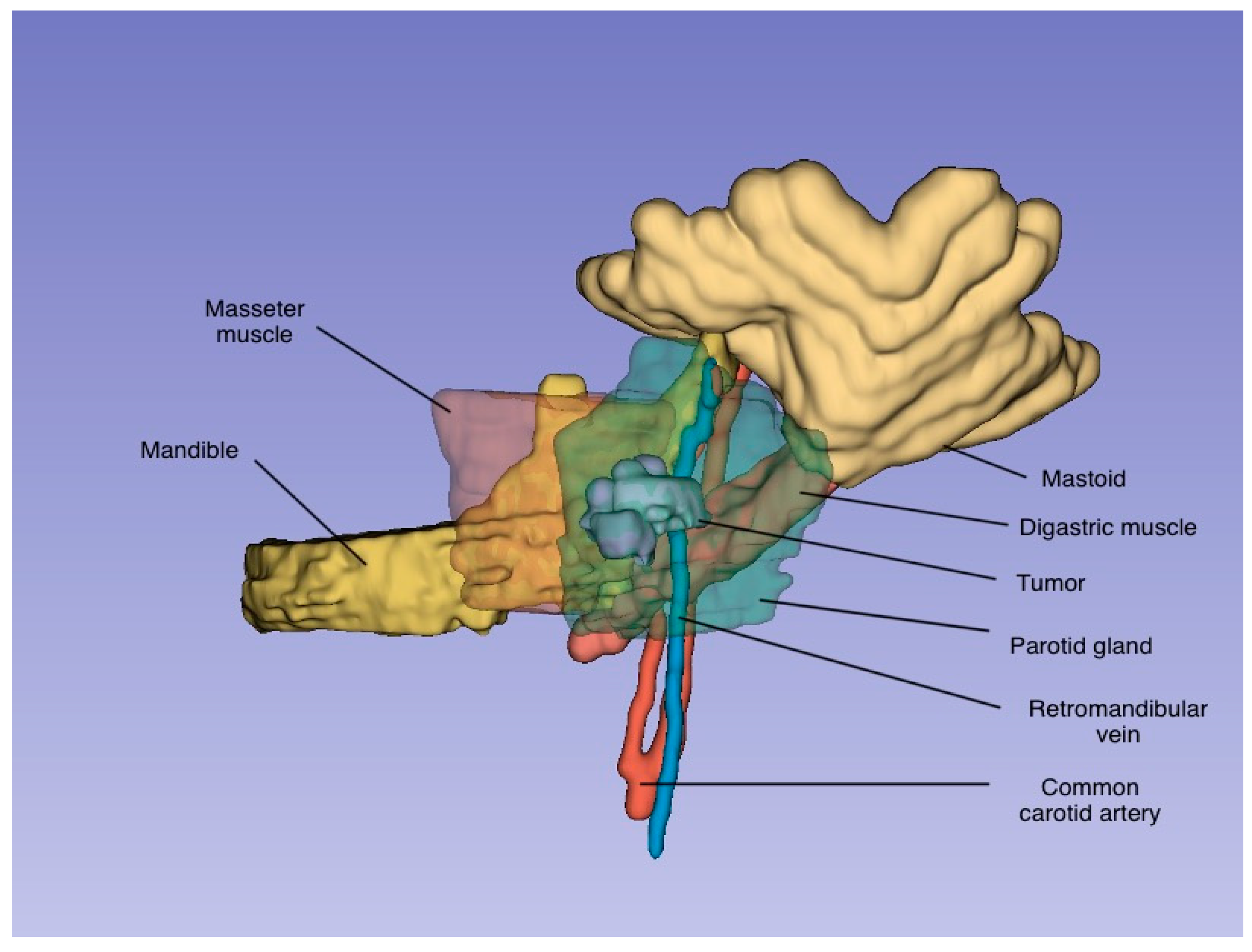

4. Clinical Case

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NS | Necrotizing sialometaplasia |

| F | Female |

| M | Male |

| NM | Not mentioned |

| US | Ultrasonography |

| FNAB | Fine-needle aspiration biopsy |

| GA | Gallium |

| NA | Not any |

| DWI | Diffusion-Weighted Imaging |

| ADC | Apparent Diffusion Coefficient |

References

- Batsakis, J.G.; Manning, J.T. Necrotizing sialometaplasia of major salivary glands. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1987, 101, 962–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, O.; Yilmaz, T.; Özer, F.; Saraç, S.; Sökmensüer, C. Necrotizing sialometaplasia of parotid gland: A possible vasculitic cause. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2002, 64, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, T.; Nishide, Y.; Nakano, H.; Kida, K.; Satoh, K. Imaging findings of necrotizing sialometaplasia of the parotid gland: Case report and literature review. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2014, 43, 20140127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sneige, N.; Batsakis, J.G. Necrotizing sialometaplasia. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1992, 101, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannon, R.B.; Fowler, C.B.; Hartman, K.S. Necrotizing sialometaplasia: A clinicopathologic study of sixty-nine cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1991, 72, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, K. Pathohistology of necrotizing sialometaplasia in parotid glands. Laryngol. Rhinol. Otol. 1979, 58, 70–76. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakaran, V.C.; Flora, R.S.; Kendall, C. Pressure-induced necrotizing sialometaplasia of the parotid gland. Histopathology 2006, 48, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, T.; Harada, M.; Umekita, Y.; Taguchi, S.; Higashi, M.; Nakamura, D.; Suzuki, S.; Tanimoto, A. Necrotizing sialometaplasia of the parotid gland associated with angiocentric T-cell lymphoma: A case report and review of the literature. Pathol. Int. 2010, 60, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Joo, Y.H.; Oh, J.H. A case of necrotizing sialometaplasia involving bilateral parotid glands. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2013, 34, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stodulski, D.; Majewska, H.; Skálová, A.; Mikaszewski, B.; Biernat, W.; Stankiewicz, C. Histological reclassification of parotid gland carcinomas: Importance for clinicians. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 3937–3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haen, P.; Ben Slama, L.; Goudot, P.; Schouman, T. Necrotizing sialometaplasia of the parotid gland associated with facial nerve paralysis. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 118, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhurakivska, K.; Maiorano, E.; Nocini, R.; Mignogna, M.D.; Favia, G.; Troiano, G.; Arena, C.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Muzio, L.L. Necrotizing sialometaplasia can hide the presence of salivary gland tumors: A case series. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 1084–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkholz, H.; Brownd, C.L. Necrotizing sialometaplasia: Report of an ulcerative case. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1981, 103, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standish, S.M.; Shafer, W.G. Serial histologic effects of rat submaxillary and sublingual salivary gland duct and blood vessel ligation. J. Dent. Res. 1957, 36, 866–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioguardi, M.; Santarelli, A.; Compilato, D.; Campisi, G.; Muzio, L.L. Salivary gland tumors in patients with necrotizing sialometaplasia: A case series. Ann. Stomatol. 2013, 4 (Suppl. S2), 16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taxy, J.B. Necrotizing squamous/mucinous metaplasia in oncocytic salivary gland tumors. A potential diagnostic problem. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1992, 97, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anneroth, G.; Hansen, L.S. Necrotizing sialometaplasia: The relationship of its pathogenesis to its clinical characteristics. Int. J. Oral Surg. 1982, 11, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.A.; Raymond, J.M.; Francis, V.H. Necrotizing sialometaplasia: A disease simulating malignancy. Cancer 1973, 32, 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, Y.L.; Johnson, J.T.; Myers, E.N. Squamous cell carcinoma of the parotid gland. Head Neck 2006, 28, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.M.; Roman, S.A.; Sosa, J.A.; Judson, B.L. Prognostic factors for squamous cell cancer of the parotid gland: An analysis of 2104 patients. Head Neck 2015, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoia, S.; Lenghel, M.; Dinu, C.; Tamaș, T.; Bran, S.; Băciuț, M.; Boțan, E.; Leucuța, D.; Armencea, G.; Onișor, F.; et al. The value of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in the preoperative differential diagnosis of parotid gland tumors. Cancers 2023, 15, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karaman, C.Z.; Tanyeri, A.; Ozgur, R.; Ozturk, V.S. Parotid gland tumors: Comparison of conventional and diffusion-weighted MRI findings with histopathological results. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2021, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Merino Domingo, F.; Martín Medina, P.; López Fernández, P.; Zafra Vallejo, V.; Salvador Álvarez, E.; Gutiérrez Díaz, R.; Sánchez Aniceto, G.; Ramos, A. Advanced MRI sequences (diffusion and perfusion): Its value in parotid tumors. Int. Arch. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Soylemez, O.U.; Atalay, B. Differentiation of benign and malignant parotid gland tumors with MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging. Medeni Med. J. 2021, 36, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Faheem, M.H.; Shady, S.; Refaat, M.M. Role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) including diffusion-weighted images (DWIs) in assessment of parotid gland masses with histopathological correlation. Egypt J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2018, 49, 368–373. [Google Scholar]

- Kawagishi, N.; Takahashi, H.; Hashimoto, Y.; Miyamoto, K.; Iizuka, H. A case of Lyme disease with parotitis. Dermatology 1998, 197, 386–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suomalainen, A.; Tornwall, J.; Hagstrom, J. CT findings of necrotizing sialometaplasia. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2012, 41, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aničin, A.; Jerman, A.; Urbančič, J.; Pušnik, L. Sialendoscopy-Based Analysis of Submandibular Duct Papillae with a Proposal for Classification. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.H.; Holsinger, F.C. Squamous cell carcinoma of parotid gland associated with concurrent lymphoepithelial cysts and lymphoepithelial lesion: Case report and proposed histogenesis. Head Neck Pathol. 2015, 9, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Skálová, A.; Hyrcza, M.D.; Leivo, I. Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors: Salivary Glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2022, 16, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.A.; Nakaguro, M.; Weinreb, I.; Palsgrove, D.; Rooper, L.M.; Vandergriff, T.W.; Carlile, B.; Sorelle, J.A.; Gagan, J.; Nagao, T. Comprehensive next-generation sequencing reveals that purported primary squamous cell carcinomas of the parotid gland are genetically heterogeneous. Head Neck Pathol. 2024, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Slater, L.J. Parotid necrotizing sialometaplasia vs infarcted Warthin tumour. Dentomaxillofacial Radiol. 2015, 44, 20140392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.B.; Posantes, G.E.M.; Gonçalves, L.S.S.; da Silva, A.T.F.; Silveira, H.A.; Chahud, F.; León, J.E. Multifocal necrotizing sialometaplasia in the tongue surgical specimen: An immunohistochemical study. Head Neck Pathol. 2025, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giunchi, F.; Bulatao, I.S. Necrotizing sialometaplasia within a benign mixed tumor of the parotid gland. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 20, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnepp, D.R. Warthin tumor exhibiting sebaceous differentiation and necrotizing sialometaplasia. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1981, 391, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case | Year | Author | Age (Years)/Sex | Cause | Size | Left/Right/Bilateral Parotid | Clinical Presentation | Preoperative Examination | Treatment | Primary Histologic Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–6 | 1979 | Donath [6] | Mean age of M: 54.5 Mean age of F: 49 Sex ratio: M:F = 1:2 | Postoperative vascular injuries (11/13) | 0.6–1.0 cm (mean of 6 cases) | NM | Painless ulcer: 70% Nonulcerative mass: 30% Local pain: 26% | NM | Surgical resection | 2× pleomorphic adenoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, myoepitelioma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, lobular sialadenitis |

| 7–13 | 1987 | Batsakis and Manning [1] | ||||||||

| 14–19 | 1991 | Brannon et al. [5] | NM | Postoperative vascular injuries (5/6 cases) | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| 20 | 2002 | Aydin et al. [2] | 17/F | Vascular injury | 2 cm | Right | Pain Swelling of neck | US/CT FNAB | Superficial parotidectomy | NM |

| 21 | 2006 | Prabhakaran [7] | 32/M | Pressure-induced ischaemia | NM | NM | Swelling of neck Pus discharge from parotid duct | Biopsy CT | NM | Parotid abscess |

| 22 | 2010 | Yoshioka [8] | 66/M | Malignant lymphoma | NM | NM | Swelling of neck Swelling of pharynx Vocal cord paralysis Neck lymphadenopathy | FNAB | NM | NM |

| 23 | 2013 | Kim et al. [9] | 69/F | Vascular injury owing to heavy smoking | 3 × 2, 1.5 × 1.5 | Bilateral | Swelling of neck | CT FNAB | Superficial parotidectomy | NM |

| 24 | 2016 | Stodulski et al. [10] | 35/F | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | NM | Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma |

| 25 | 2017 | Haen et al. [11] | 56/M | Spontaneous hematoma due to overdose of anticoagulant treatment and vascular fragility related to Marfan syndrome | 3 × 4 cm | Left | Parotid swelling, inflammation, progressively complete facial nerve paralysis | CT MRI FNAB Open biopsy | NA | Parotiditis Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

| 26–29 | 2019 | Zhurakivska et al. [12] | 45/M | Surgical trauma (FNAB) and/or tumor growth | NM | NM | Parotid gland swelling; slow growth; no facial nerve palsy | US CT FNAB | Total parotidectomy | NM |

| 51/M | NM | NM | Parotid gland swelling; slow growth; no facial nerve palsy | Superficial parotidectomy | NM | |||||

| 63/M | NM | NM | Parotid gland swelling | Superficial parotidectomy | NM | |||||

| 27/M | NM | NM | Parotid gland swelling | Superficial parotidectomy | NM | |||||

| 30 | 2024 | Current report | 23/F | Lyme disease | 2 × 1.5 cm | Left | Swelling of neck Pain | Biopsy US CT IRM | Superficial parotidectomy and selective neck dissection | Inflammatory lymph node/squamous cell carcinoma |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mocan, R.; Dinu, C.; Stoia, S.; Baciut, G.; Bran, S.; Lenghel, M.; Tamas, T.; Armencea, G.; Botan, E.; Onisor, F.; et al. Advanced Diagnostic Methods in Necrotizing Sialometaplasia of the Parotid Glands: An Updated Literature Review and a Rare Case Report. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072290

Mocan R, Dinu C, Stoia S, Baciut G, Bran S, Lenghel M, Tamas T, Armencea G, Botan E, Onisor F, et al. Advanced Diagnostic Methods in Necrotizing Sialometaplasia of the Parotid Glands: An Updated Literature Review and a Rare Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(7):2290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072290

Chicago/Turabian StyleMocan, Rares, Cristian Dinu, Sebastian Stoia, Grigore Baciut, Simion Bran, Manuela Lenghel, Tiberiu Tamas, Gabriel Armencea, Emil Botan, Florin Onisor, and et al. 2025. "Advanced Diagnostic Methods in Necrotizing Sialometaplasia of the Parotid Glands: An Updated Literature Review and a Rare Case Report" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 7: 2290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072290

APA StyleMocan, R., Dinu, C., Stoia, S., Baciut, G., Bran, S., Lenghel, M., Tamas, T., Armencea, G., Botan, E., Onisor, F., & Baciut, M. (2025). Advanced Diagnostic Methods in Necrotizing Sialometaplasia of the Parotid Glands: An Updated Literature Review and a Rare Case Report. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(7), 2290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14072290