Clinical Practice Preferences for Glaucoma Surgery in Japan in 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Surgical Choices for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma

3.1.1. Mild to Moderate Cases (MD > −12 dB)

3.1.2. Advanced Cases (MD ≤ −12 dB)

3.2. Surgical Choices for Normal Tension Glaucoma

3.2.1. Mild to Moderate Cases (MD > −12 dB)

3.2.2. Advanced Cases (MD ≤ −12 dB)

3.3. Surgical Choices for Uveitic Glaucoma

3.4. Surgical Choices for Neovascular Glaucoma

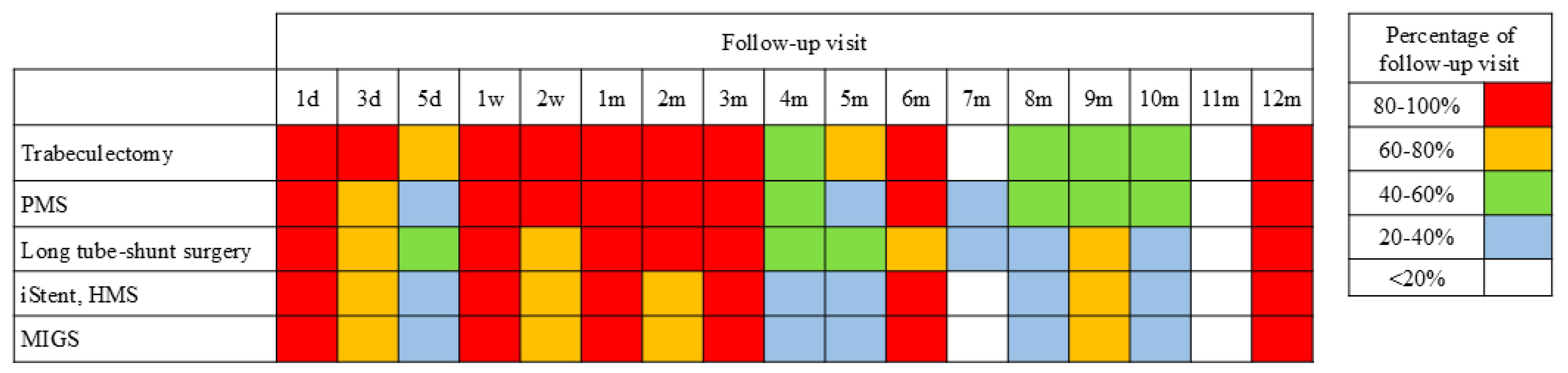

3.5. Postoperative Management

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costa, V.P.; Smith, M.; Spaeth, G.L.; Gandham, S.; Markovitz, B. Loss of visual acuity after trabeculectomy. Ophthalmology 1993, 100, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, M.V.; Corcoran, K.J.; Lee, A.Y. Changes in performance of glaucoma surgeries 1994 through 2017 based on claims and payment data for United States Medicare beneficiaries. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2021, 4, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luebke, J.; Boehringer, D.; Anton, A.; Daniel, M.; Reinhard, T.; Lang, S. Trends in surgical glaucoma treatment in Germany between 2006 and 2018. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 13, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, K.; Arimura, S.; Takamura, Y.; Inatani, M. Clinical practice preferences for glaucoma surgery in Japan: A survey of Japan Glaucoma Society specialists. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 64, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, S.; Andrews, C.A.; Greenfield, D.S.; Stein, J.D. Trends in Glaucoma Surgeries Performed by Glaucoma Subspecialists versus Nonsubspecialists on Medicare Beneficiaries from 2008 through 2016. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.A.; Mitchell, W.; Hall, N.; Elze, T.; Lorch, A.C.; Miller, J.W.; Zebardast, N.; IRIS® Registry Data Analytics Consortium. Trends and usage patterns of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery in the United States: IRIS® registry analysis 2013–2018. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2021, 4, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yook, E.; Vinod, K.; Panarelli, J.F. Complications of micro-invasive glaucoma surgery. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 29, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosdahl, J.A.; Gupta, D. Prospective studies of minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries: Systematic review and quality assessment. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 14, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, J.F.; Fantes, F.; Riss, I.; Pinchuk, L.; Alburquerque, R.; Kato, Y.P.; Arrieta, E.; Peralta, A.C.; Palmberg, P.; Parrish, R.K., 2nd; et al. Three-year follow-up of a novel aqueous humor MicroShunt. J. Glaucoma 2016, 25, e58–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.S.; Robin, A.L.; Corcoran, K.J.; Corcoran, S.L.; Ramulu, P.Y. Use of various glaucoma surgeries and procedures in Medicare beneficiaries from 1994 to 2012. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1615–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.A.; Gedde, S.J.; Feuer, W.J.; Shi, W.; Chen, P.P.; Parrish, R.K., 2nd. Practice preferences for glaucoma surgery: A survey of the American Glaucoma Society in 2008. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging 2011, 42, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinod, K.; Gedde, S.J.; Feuer, W.J.; Panarelli, J.F.; Chang, T.C.; Chen, P.P.; Parrish, R.K., 2nd. Practice preferences for glaucoma surgery: A survey of the American Glaucoma Society. J. Glaucoma 2017, 26, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Una, I.; Azuara-Blanco, A.; King, A.J. Survey of glaucoma surgical preferences and post-operative care in the United Kingdom. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2017, 45, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, A.; Hashimoto, Y.; Matsui, H.; Yasunaga, H.; Aihara, M. Recent trends in glaucoma surgery: A nationwide database study in Japan, 2011–2019. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 66, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanito, M. Nationwide analysis of glaucoma surgeries in fiscal years of 2014 and 2020 in Japan. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, Y.; Kasahara, M.; Hirasawa, K.; Tsujisawa, T.; Kanayama, S.; Matsumura, K.; Morita, T.; Shoji, N. Long-term clinical results of trabectome surgery in patients with open-angle glaucoma. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 258, 2467–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, G.M.; Takusagawa, H.L.; Sit, A.J.; Rosdahl, J.A.; Chopra, V.; Ou, Y.; Kim, S.J.; WuDunn, D. Trabecular Procedures Combined with Cataract Surgery for Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanito, M.; Sugihara, K.; Tsutsui, A.; Hara, K.; Manabe, K.; Matsuoka, Y. Midterm Results of Microhook ab Interno trabeculotomy in Initial 560 Eyes with Glaucoma. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, K.; Arimura, S.; Takihara, Y.; Takamura, Y.; Inatani, M. Prospective cohort study of corneal endothelial cell loss after Baerveldt glaucoma implantation. PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, e0201342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarz-Barberá, M.; Morales-Fernández, L.; Corroto-Cuadrado, A.; Martinez-Galdón, F.; Tañá-Rivero, P.; Gómez de Liaño, R.; Teus, M.A. Corneal Endothelial Cell Loss After PRESERFLO™ MicroShunt Implantation in the Anterior Chamber: Anterior Segment OCT Tube Location as a Risk Factor. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2022, 11, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panarelli, J.F.; Moster, M.R.; Garcia-Feijoo, J.; Flowers, B.E.; Baker, N.D.; Barnebey, H.S.; Grover, D.S.; Khatana, A.K.; Lee, B.; Nguyen, T.; et al. Ab-Externo MicroShunt versus trabeculectomy in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Two-year Results from a Randomized, Multicenter Study. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwase, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Araie, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Abe, H.; Shirato, S.; Kuwayama, Y.; Mishima, H.K.; Shimizu, H.; Tomita, G.; et al. The prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma in Japanese: The Tajimi Study. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oie, S.; Ishida, K.; Yamamoto, T. Impact of intraocular pressure reduction on visual field progression in normal-tension glaucoma followed up over 15 years. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 61, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, K.; Sakata, R.; Ueda, K.; Fujita, A.; Fujishiro, T.; Honjo, M.; Shirato, S.; Aihara, M. Central visual field change after fornix-based trabeculectomy in Japanese normal-tension glaucoma patients managed under 15 mmHg. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 259, 2309–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, P.G.; Zhang, D.; Budenz, D.L.; Barton, K.; Tsai, J.C.; Ahmed, I.I.K.; ABC-AVB Study Groups. Five-year pooled data analysis of the Ahmed Baerveldt comparison study and the Ahmed versus Baerveldt study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 176, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, K.; Kojima, S.; Wajima, R.; Matsuda, A.; Yoshida, K.; Tsutsui, A.; Kono, M.; Nozaki, M.; Namiguchi, K.; Nitta, K.; et al. Surgical Outcomes of Baerveldt Glaucoma Implant Versus Ahmed Glaucoma Valve in Neovascular Glaucoma: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Adv. Ther. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, D.; Lieb, W.E.; Grehn, F. Intensified postoperative care versus conventional follow-up: A retrospective long-term analysis of 177 trabeculectomies. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2004, 242, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panarelli, J.F.; Nayak, N.V.; Sidoti, P.A. Postoperative management of trabeculectomy and glaucoma drainage implant surgery. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 27, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.C.; Vanner, E.A.; Parrish, R.K., 2nd. Glaucoma surgery preferences when the surgeon adopts the role of the patient. Eye 2019, 33, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, D.C.; Louzada, R.N.; Moreira, P.H.S.; de Oliveira, L.N.; Yuati, T.T.; Guedes, J.; Alves, M.R.; Mora-Paez, D.J.; Monteiro, M.L.R. Combined endoscopic cyclophotocoagulation and phacoemulsification versus phacoemulsification alone in the glaucoma treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e55853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Crom, R.M.P.C.; Kujovic-Aleksov, S.; Webers, C.A.B.; Berendschot, T.T.J.M.; Beckers, H.J.M. Long-term treatment outcomes of micropulse transscleral cyclophotocoagulation in primary and secondary glaucoma: A 5-year analysis. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2025, 14, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Glaucoma Surgery | Unoperated Eyes with Cataract | Unoperated Eyes Without Cataract | Pseudophakic Eyes with a Corneal Incision Phaco | Pseudophakic Eyes with a Previous Failed Trabeculectomy | Pseudophakic Eyes with Two Failed Trabeculectomies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild to Moderate (%) | Advanced (%) | Mild to Moderate (%) | Advanced (%) | Mild to Moderate (%) | Advanced (%) | Advanced (%) | Advanced (%) | |

| Microhook+Phaco | 51.8 | 24.8 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Microhook | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.8 | 5.9 | 48.4 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| iStent inject W+Phaco | 18.1 | 3.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| iStent inject W | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| KDB+Phaco | 7.1 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| KDB | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.5 | 0.0 | 7.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Suture trabeculotomy+Phaco | 6.7 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Suture trabeculotomy | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 | 1.6 | 7.9 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| HMS+Phaco | 6.1 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other MIGS+Phaco | 4.8 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other MIGS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| PMS+Phaco | 4.8 | 28.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| PMS | 0.0 | 1.6 | 17.5 | 32.9 | 23.4 | 40.1 | 18.2 | 7.1 |

| Trabeculectomy+Phaco | 0.0 | 20.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Trabeculectomy | 0.6 | 9.7 | 5.1 | 52.0 | 7.5 | 49.6 | 57.2 | 15.7 |

| ExPRESS+Phaco | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| ExPRESS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| AGV | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.7 | 49.0 |

| BGI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 20.4 |

| Bleb revision or needling | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.1 | 1.6 |

| MP-TSCPC | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.8 |

| Type of Glaucoma Surgery | Unoperated Eyes with Cataract | Unoperated Eyes Without Cataract | Pseudophakic Eyes with a Corneal Incision Phaco | Pseudophakic Eyes with a Previous Failed Trabeculectomy | Pseudophakic Eyes with Two Failed Trabeculectomies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild to Moderate (%) | Advanced (%) | Advanced (%) | Advanced (%) | Advanced (%) | Advanced (%) | |

| Microhook+Phaco | 37.5 | 21.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Microhook | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| iStent inject W+Phaco | 14.5 | 4.1 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| iStent inject W | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| KDB+Phaco | 4.8 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Suture trabeculotomy+Phaco | 2.0 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Suture trabeculotomy | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| HMS+Phaco | 6.1 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other MIGS+Phaco | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Phaco only | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| PMS+Phaco | 20.2 | 17.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| PMS | 2.4 | 0.8 | 19.1 | 25.8 | 11.1 | 9.9 |

| Trabeculectomy+Phaco | 7.1 | 36.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Trabeculectomy | 0.6 | 12.1 | 72.4 | 69.4 | 75.0 | 18.7 |

| ExPRESS+Phaco | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| ExPRESS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| AGV | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 34.1 |

| BGI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 20.6 |

| Bleb revision or needling | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.1 | 9.5 |

| MP-TSCPC | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 |

| Type of Glaucoma Surgery | Unoperated Eyes with Cataract | Unoperated Eyes Without Cataract | Pseudophakic Eyes | Pseudophakic Eyes with a Previous Failed Trabeculectomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microhook+Phaco | 20.2 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Microhook | 2.4 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 3.2 |

| iStent inject W | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| KDB+Phaco | 4.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| KDB | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| Suture trabeculotomy+Phaco | 5.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Suture trabeculotomy | 0.0 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 0.6 |

| HMS+Phaco | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other MIGS+Phaco | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other MIGS | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| PMS+Phaco | 7.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| PMS | 2.4 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 13.1 |

| Trabeculectomy+Phaco | 32.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Trabeculectomy | 20.2 | 62.7 | 57.2 | 53.7 |

| AGV+Phaco | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| AGV | 0.0 | 0.8 | 7.5 | 20.8 |

| BGI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.8 |

| Bleb revision or needling | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| Type of Glaucoma Surgery | Pseudophakic Eyes with Prior Vitrectomy and Panretinal Photocoagulation | Pseudophakic Eyes with Prior Vitrectomy, Panretinal Photocoagulation, and a Previous Failed Trabeculectomy |

|---|---|---|

| PMS | 8.4 | 4.8 |

| Trabeculectomy | 47.2 | 19.8 |

| ExPRESS | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| AGV | 34.1 | 62.7 |

| BGI | 9.1 | 10.3 |

| Bleb revision or needling | 0.0 | 2.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iwasaki, K.; Arimura, S.; Takamura, Y.; Inatani, M. Clinical Practice Preferences for Glaucoma Surgery in Japan in 2024. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062039

Iwasaki K, Arimura S, Takamura Y, Inatani M. Clinical Practice Preferences for Glaucoma Surgery in Japan in 2024. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(6):2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062039

Chicago/Turabian StyleIwasaki, Kentaro, Shogo Arimura, Yoshihiro Takamura, and Masaru Inatani. 2025. "Clinical Practice Preferences for Glaucoma Surgery in Japan in 2024" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 6: 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062039

APA StyleIwasaki, K., Arimura, S., Takamura, Y., & Inatani, M. (2025). Clinical Practice Preferences for Glaucoma Surgery in Japan in 2024. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(6), 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14062039