Abstract

Background/Objectives: Endometriosis affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age and about 47% of adolescents with pelvic pain. Symptoms include dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain (CPP). Adolescents often present atypical symptoms that can make endometriosis more difficult to diagnose. This study aimed to compare characteristics of pain, atypical symptoms, and the effects of hormonal treatments between adolescents and adults with endometriosis. Methods: A total of 238 women with endometriosis were included: 92 aged 12–18 (group A) and 146 over 18 (group B). Data on menarches, cycle length, comorbidities, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, CPP, analgesic use, pain characteristics, atypical symptoms, and endometrioma size were recorded. The efficacy, compliance, and side effects of hormonal treatments were also assessed. Quality of life (QoL) was measured using the SF-12 questionnaire at baseline and after six months of therapy. Results: Adolescents had earlier menarche (p < 0.001), longer menstrual periods (p < 0.001), and higher analgesic use (p = 0.001) compared to adults. Dysmenorrhea was more frequent (p = 0.01), lasted longer (p < 0.001), and was associated with higher pain scores (p < 0.001) in adolescents. CPP was more common in adolescents (p < 0.001), often described as “confined” (p = 0.04) and “oppressive” (p = 0.038), while adults reported it as “widespread” (p = 0.007). Headaches (p < 0.001) and nausea (p = 0.001) were also more frequent in adolescents. Both groups showed significant improvement in QoL with hormonal treatment (p < 0.001) and reported minimal side effects. Conclusions: Adolescents with endometriosis often present with earlier menarche, longer menstrual periods, more severe dysmenorrhea, and atypical symptoms. Hormonal contraceptives and dienogest are effective and safe treatments that improve pain and QoL.

1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen-dependent, inflammatory disease characterized by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity. It affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age [1], and it is mainly associated with symptoms such as dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain (CPP) [2,3]. Infertility occurs in 30–50% of cases [4]. In adolescents with pelvic pain, the prevalence of histologically confirmed endometriosis is about 47% [5]. However, the prevalence is likely higher, with estimates reaching up to 75% in adolescents who experience pain unresponsive to analgesics or hormonal treatments [6,7]. Risk factors for early-onset endometriosis include early menarche, low body mass index (BMI), family history, genetic and environmental factors, neonatal uterine bleeding, and Müllerian anomalies [8,9,10]. Inflammation also plays a key role in the pathogenesis of the disease [11,12]. Vitamin D deficiency seems to be associated with pain symptoms, and vitamin D supplementation may be effective for managing both primary and secondary dysmenorrhea in teenagers [13,14,15,16]. Adolescents with endometriosis often report more intense dysmenorrhea compared to adults [17], which is typically described as suprapubic pain radiating to the legs and lower back [18]. This is frequently accompanied by heavy menstrual bleeding in up to 44% of cases or irregular and abnormal uterine bleeding in 60% of cases [9], potentially due to the presence of adenomyosis [19,20]. In young patients, endometriosis may also debut with atypical symptoms [21] such as genitourinary symptoms, nausea, dyschezia, painful bowel movements, constipation or diarrhea, pain during exercise, depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances during menses, migraines, or severe headache [6,17,22,23]. These symptoms manifest earlier in life among adolescents with endometriosis and can debilitate, leading to school absenteeism, negatively affecting social relationships and significantly impairing their quality of life (QoL) [19,21,24,25,26].

The primary objective of this prospective cohort study was to analyze the symptoms and pain characteristics in adolescents aged 12 to 18 years with endometriosis, compared to adult women diagnosed with endometriosis over the age of 18. The secondary objectives were to improve diagnostic accuracy by identifying specific symptoms, thereby facilitating personalized treatments that may delay the need for surgery, optimize pain management, and enhance QoL. Additionally, the study assessed the efficacy, adherence, and side effects of hormonal treatments in adolescents.

2. Materials and Methods

Patients with endometriosis referred to the Endometriosis Outpatient Service of Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, between 1 January 2021 and 31 March 2024 were enrolled in this prospective cohort study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (approval number 0794/2020, approved on 28 October 2020). Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their parents if the patients were underage. Patients diagnosed with endometriosis between 12 and 18 years were included in group A, while those diagnosed over 18 years old were included in group B. Inclusion criteria were age between 12 and 45 years and a first clinical–instrumental (transvaginal/transrectal ultrasound and/or magnetic resonance imaging, where appropriate) diagnosis of endometriosis received within 6 months of recruitment. Exclusion criteria were as follows: pre-menarche or menopause status, prior adnexectomy (unilateral or bilateral) or surgical treatment for endometriosis, active cancer, pelvic inflammatory disease or any other gynecological infections, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and previous or current medical treatment with hormonal contraceptives or progestogens. Each patient’s medical history was carefully evaluated by the same gynecologist at baseline and after 6 months. The following factors were recorded: age at menarche, length of periods, BMI, comorbidities, presence of adenomyosis or deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE), and size of ovarian endometriomas. The presence, intensity (measured using a 10-point visual numerical scale (VNS)), duration of dysmenorrhea, premenstrual or intermenstrual pain, CPP and dyspareunia, and the use of non-steroidal analgesics (NSAIDs) were recorded. Particular attention was given to the presence of symptoms, such as spotting, heavy menstrual bleeding, mastodynia, gastrointestinal symptoms, bloating, urinary symptoms, headache, low back pain, and nausea. All patients underwent a gynecological examination or, when possible, a transvaginal ultrasound. Alternatively, a transabdominal or transrectal pelvic ultrasound was performed. In selected cases, patients also underwent pelvic MRI. Hormonal treatment with dienogest (2 mg/die) or combined estrogen–progestin therapy (levonorgestrel 0.1 mg/ethinyl estradiol 0.02 mg) administered in a continuous regimen (COC) was proposed. The choice of therapy was based on the patient’s preferences and need for contraception. Data regarding the type of therapy, route of administration, effectiveness, and potential side effects were evaluated both at the time of recruitment and after 6 months. All patients filled in the SF-12 validated questionnaire at the recruitment and after 6 months of treatment to assess the health-related QoL. The scoring system, calibrated to the American population, considers an average score of 50 as indicative of “good health” [27].

Data Analysis

The sample size was calculated on the basis of an expected prevalence of endometriosis among adolescents with pelvic pain of 25–38%, with a statistical power of 90% and a significance level of 5%. All the data were collected in an Excel worksheet. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 25 for iMac; IBM, SPSS Statistics, Bologna, Italy). A preliminary descriptive analysis was performed to obtain average values and standard deviations (SD) regarding patients’ general characteristics (continuous variables) and average size of ovarian endometriomas. Quantitative variables were evaluated using the Chi-square test. Normally distributed continuous variables were evaluated using the Student t-test, while the non-normally distributed ones were evaluated using the U-test of Mann–Whitney. Statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

Two hundred and thirty-eight patients were enrolled in this prospective cohort study. Of these, 92 were assigned to Group A (mean age 15.8 ± 1.7 years, range 12–18 years old) and 146 to Group B (mean age 33.9 ± 4.5 years, range 19–45 years old). The general characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics.

All patients presented with ovarian endometriomas, with an average size of 36.31 ± 22.5 mm in Group A and 29.21 ± 20.3 mm in Group B (p > 0.05). Adenomyosis was identified in 4.3% (n = 4) of patients in Group A and 14.3% (n = 21) of patients in Group B (p = 0.04). DIE was present in 9.7% (n = 9) of patients in Group A and 17.8% (n = 26) in Group B (p = 0.04).

No statistically significant differences were observed in biometric characteristics, urinary and bowel diseases, or medical history, except for a higher prevalence of autoimmune thyroiditis in Group B (9.58%, p = 0.035). The main results of the study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence and intensity of symptoms.

Intermenstrual pain was complained of by 39.1% (n = 36) of the patients in Group A and 26% (n = 38) in Group B (p > 0.05). Among these, 94.4% (n = 34) of patients in Group A and 84.2% (n = 32) in Group B described the pain as located mainly in the lateral areas of the lower quadrants of the abdomen (p = 0.037). Only 11 patients (11.9%) of group A had sexual intercourse and 3 (27.2%) reported deep dyspareunia with an average VNS score of 7.85 ± 2. In group B, 58 patients (39.7%) had deep dyspareunia with an average VNS score of 5.79 ± 2.

Eighty-four patients of group A (91.3%) and one hundred and twenty-one patients of group B (82.8%) received oral hormonal treatment with monophasic, low-dose, continuous COC or dienogest. After six months, only five patients of group A (5.9%) and eight patients of group B (6.6%) had discontinued the treatment due to side effects including vaginal bleeding, headache, and mood changes (more frequently observed among patients taking dienogest) (p > 0.05).

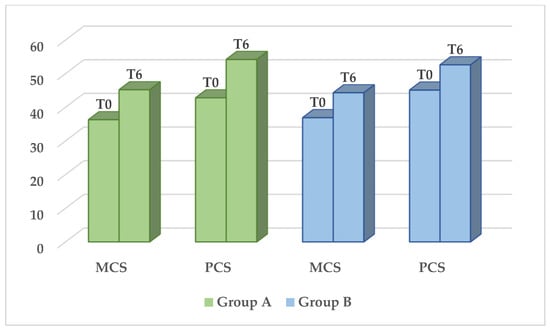

The SF-12 questionnaire showed a significant improvement in the QoL in both groups, regardless of the type of treatment. The average mental component score increased from 36.3 ± 11.4 to 45.2 ± 9.9 in group A (p < 0.001) and from 36.9 ± 10.1 to 44.3 ± 11.1 in group B (p < 0.001). The average physical component score increased from 42.8 ± 10.4 to 54.2 ± 7.9 in group A (p < 0.001) and from 45.1 ± 9.7 to 52.6 ± 7.4 in group B (p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

QoL through the means of the SF-12 questionnaire. Significant difference in MCS e PCS (p < 0.001) before (T0) and six months after treatment (T6). No statistically significant difference between the two groups. (MCS = mental component score, PCS = physical component score).

4. Discussion

Endometriosis is a chronic condition that affects women of reproductive age, often beginning during puberty or in early adolescence. In adolescents, the diagnosis is frequently delayed by up to 11 years, hindering timely identification and treatment and significantly impacting their QoL [20,28]. This delay is largely due to the differences in symptom presentation compared to adults [29]. Dysmenorrhea and pelvic pain can significantly impair school performance, daily activities, relationships, and social engagement [21,24,25,26]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recognizes endometriosis as the leading cause of secondary dysmenorrhea that does not respond to treatment with NSAIDs or hormonal suppression in adolescents. They recommend a whole abdominal and pelvic examination (via gynecological visit and transvaginal ultrasound) to rule out other potential conditions, such as obstructive anomalies of the genitourinary tract or bowel diseases [30,31]. However, gynecological examinations or transvaginal pelvic ultrasounds cannot be performed on adolescents who have never had sexual intercourse, and transrectal ultrasound is often unaccepted. MRI may be needed in selected cases to confirm the suspicion of endometriosis [32,33]. Therefore, it is essential to maintain a high index of suspicion and look for signs and symptoms that could facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment, potentially improving pain management and slowing disease progression [9,29]. In this regard, we observed a significant association between confined and oppressive CPP, nausea, and headache in young patients with endometriosis. On the other hand, adults were significantly more often affected by autoimmune thyroiditis, which aligns with the expected increase in autoimmune diseases in older women [34]. Despite evidence suggesting an inverse relationship between endometriosis and BMI [35], we did not find any statistically significant difference between adolescents and adults, possibly due to the small sample size. Similarly, no differences were observed in the size of ovarian endometriomas, in contrast to the findings of Brosens et al., who reported larger ovarian endometriomas in a significant proportion of adolescents with early-onset endometriosis [36]. However, our results align with those of Smorgick et al., who found that most adolescents present with early-stage disease. In addition, we found a low rate of DIE in adolescents according to the literature [36,37]. Nevertheless, our data may underestimate the actual presence of DIE, as several young patients were unable to undergo transvaginal ultrasound, refused transrectal ultrasound, and only a small proportion of them underwent MRI.

A meta-analysis published in 2012 reported that early menarche is associated with a slightly increased risk of endometriosis [8,23]. Consistent with this finding, we observed that adolescents with endometriosis tend to have earlier menarche compared to those diagnosed in adulthood and experience both typical and atypical pelvic pain from their first menstrual period. Additionally, a long menstrual cycle length is a well-established risk factor for endometriosis [38], as it leads to prolonged exposure to menstrual bleeding, increased retrograde flow through the fallopian tubes, and persistence of a pro-inflammatory state within the pelvis [39].

Secondary dysmenorrhea due to endometriosis is often associated with worsening pain, CPP, mid-cycle or acyclic pain, and irregular or heavy menstrual bleeding [4]. This non-cyclical, moderate to severe pain may present as premenstrual and intermenstrual pain, significantly disrupting social activities and daily life. Consistently, we observed a significantly higher prevalence of intermenstrual pelvic pain among adolescents, often accompanied by atypical symptoms. Premenstrual discomfort also presented as headache and nausea in most cases.

Sieberg et al. found that a substantial proportion of young women (one-third) and adult women (64–82%) with CPP had endometriosis, suggesting a link with neuropathic sensitization and neuro-angiogenesis throughout the pelvis [40]. Conversely, Tsonis et al. reported that CPP was more common among younger patients, with an increased risk for disease progression [31]. In our study, both groups experienced CPP, but the intensity was greater in adolescents. Moreover, the characteristics of CPP differed between the groups; young patients commonly reported “localized” and/or “oppressive” pelvic pain, often accompanied by nausea and headaches, whereas adults more frequently described their pain as “widespread.” Similarly, Miller et al. found a higher prevalence of migraine in adolescents with symptomatic endometriosis, particularly those with early menarche. This association appears to be driven by estrogen exposure but, more importantly, by an increased risk of central sensitization [41]. These findings align with previous observations by Di Vasta et al. and Shim et al., who noted that both nausea and headaches were more prevalent among adolescents, significantly impacting their daily lives and social functioning [6,23].

We found no significant difference in the prevalence of dyspareunia between the two groups, although the average VNS score was higher among adolescents. These findings should be interpreted cautiously, as dyspareunia could not be assessed in sexually inactive younger patients.

The observed reduced responsiveness to NSAIDs among adolescents may be attributed to altered leukotriene receptor inhibition, changes in platelet-activating factors, or underlying neuropathic pain mechanisms [42]. Alternatively, it could be due to the use of suboptimal doses of analgesics or to patients’ reluctance to take them before the onset of pain, as recommended by clinical guidelines [30].

Furthermore, Sahin et al. reported a higher prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in young women with dysmenorrhea, which may impact pain perception [40,43]. In our study, we did not find any significant difference in mood disorders between adolescents and adults. An impaired QoL was detected by means of the SF-12 questionnaire, but physical and mental component scores improved following medical treatment in both groups.

The hormonal medical treatment with dienogest or COC was discussed with patients from both groups, considering their symptoms, need for contraception, individual preferences, and preferred route of administration. Six months after initiating therapy, patients in both groups reported an improvement in pain, lesion extent, and QoL. Consistent with the existing literature, no significant long-term side effects were observed in young patients using COC or dienogest, further supporting the conclusion that hormonal contraceptives or low-dose progestogens may be a suitable, acceptable, and safe treatment option for symptomatic endometriosis in young patients [29,44,45]. Furthermore, the number of patients who discontinued treatment was very low and not statistically significant. The main side effects reported by these patients were vaginal bleeding, headaches, and mood changes, most observed during the first three months of therapy, especially in patients taking dienogest.

5. Conclusions

The results of our study highlight the pain characteristics in adolescents with ovarian endometriosis. A key strength of the study is the observation of “pure symptoms,” unaffected by prior hormonal treatments, pregnancies, or surgeries. However, the small sample size limits the study, making these findings preliminary and requiring validation in a larger cohort.

Adolescents with endometriosis exhibit earlier menarche, longer menstrual periods, more severe dysmenorrhea, and atypical symptoms compared to women diagnosed in adulthood. Their pain is also less responsive to NSAID treatment. They more frequently experience headaches and nausea. CPP in adolescents is often described as “confined” and “oppressive,” with higher VNS scores than those reported by adults. Hormonal contraceptives and dienogest seem to be suitable, safe, and well-accepted treatments for young patients with symptomatic endometriosis, significantly improving both pain and QoL.

The findings of our study provide a basis for further research aimed at the early detection of endometriosis-related symptoms, even in young women. This approach could facilitate earlier diagnosis and tailored treatments, leading to improved clinical outcomes and QoL.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora), M.F.V. and L.M. (Ludovico Muzii); methodology, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora) and M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Piccioni).; software, M.F.V.; validation, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora), L.M. (Ludovico Muzii) and L.M. (Lucia Manganaro); formal analysis, M.F.V.; investigation, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora), M.F.V. and I.P.; resources, A.M. and L.C.; data curation, M.F.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora), M.F.V. and I.P.; writing—review and editing, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora), M.F.V. and A.M.; visualization, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora); supervision, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora) and L.M. (Ludovico Muzii); project administration, M.G.P. (Maria Grazia Porpora). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of General Hospital “Policlinico Umberto I”, University of Rome “Sapienza” (Ref. 0794/2020), date of approval 28 October 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all included patients or by a parent in the case of underage patients.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPP | chronic pelvic pain |

| BMI | body mass index |

| QoL | quality of life |

| VNS | visual numerical scale |

| NSAIDs | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| COC | combined oral contraceptives |

| ACOG | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| TVUS | transvaginal ultrasound |

References

- Giudice, L.C.; Kao, L.C. Endometriosis. Lancet 2004, 364, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masciullo, L.; Viscardi, M.F.; Piacenti, I.; Scaramuzzino, S.; Cavalli, A.; Piccioni, M.G.; Porpora, M.G. A deep insight into pelvic pain and endometriosis: A review of the literature from pathophysiology to clinical expressions. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 73, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezhat, C.; Vang, N.; Tanaka, P.P.; Nezhat, C. Optimal Management of Endometriosis and Pain. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachedina, A.; Todd, N. Dysmenorrhea, Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain in Adolescents. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2020, 12 (Suppl. 1), 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, E.C.; Kho, K.A.; Morozov, V.V.; Kearney, S.; Zurawin, J.L.; Nezhat, C.H. Endometriosis in adolescents. JSLS 2015, 19, e2015.00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y.; Laufer, M.R. Adolescent Endometriosis: An Update. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2020, 33, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E.B.; Rijkers, A.C.; Hoppenbrouwers, K.; Meuleman, C.; D’Hooghe, T.M. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Webster, P.; Kumbang, J.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T. Is early age at menarche a risk factor for endometriosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 98, 702–712.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benagiano, G.; Guo, S.W.; Puttemans, P.; Gordts, S.; Brosens, I. Progress in the diagnosis and management of adolescent endometriosis: An opinion. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2018, 36, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felip, E.; Abballe, A.; Albano, F.L.; Battista, T.; Carraro, V.; Conversano, M.; Franchini, S.; Giambanco, L.; Iacovella, N.; Ingelido, A.M.; et al. Current exposure of Italian women of reproductive age to PFOS and PFOA: A human biomonitoring study. Chemosphere 2015, 137, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galandrini, R.; Porpora, M.G.; Stoppacciaro, A.; Micucci, F.; Capuano, C.; Tassi, I.; Di Felice, A.; Benedetti-Panici, P.; Santoni, A. Increased frequency of human leukocyte antigen-E inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A-expressing peritoneal natural killer cells in patients with endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 89 (Suppl. 5), 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Liang, Y.; Lin, H.; Dai, Y.; Yao, S. Autonomic nervous system and inflammation interaction in endometriosis-associated pain. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasi, E.; Fuggetta, E.; De Vito, C.; Migliara, G.; Viggiani, V.; Manganaro, L.; Granato, T.; Panici, P.B.; Angeloni, A.; Porpora, M.G. Low levels of 25-OH vitamin D in women with endometriosis and associated pelvic pain. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2017, 55, e282–e284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nodler, J.L.; DiVasta, A.D.; Vitonis, A.F.; Karevicius, S.; Malsch, M.; Sarda, V.; Fadayomi, A.; Harris, H.R.; Missmer, S.A. Supplementation with vitamin D or ω-3 fatty acids in adolescent girls and young women with endometriosis (SAGE): A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzopoulos, D.R.; Samartzis, N.; Daniilidis, A.; Leeners, B.; Makieva, S.; Nirgianakis, K.; Dedes, I.; Metzler, J.M.; Imesch, P.; Lempesis, I.G. Effects of vitamin D supplementation in endometriosis: A systematic review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2022, 20, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradwan, S.; Gari, A.; Sabban, H.; Alshahrani, M.S.; Khadawardi, K.; Bukhari, I.A.; Alyousef, A.; Abu-Zaid, A. The effect of antioxidant supplementation on dysmenorrhea and endometriosis-associated painful symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2024, 67, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıdoğan, E. Adolescent endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 209, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, L.; Bope, E.T. Management of pelvic pain from dysmenorrhea or endometriosis. J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 2004, 17, S43–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeri, L.; Andersson, K.L.; Angioni, S.; Arena, A.; Arena, S.; Bartiromo, L.; Berlanda, N.; Bonin, C.; Candiani, M.; Centini, G.; et al. How to manage endometriosis in adolescence: The Endometriosis Treatment Italian Club approach. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rund, N.M.A.; El Shenoufy, H.; Islam, B.A.; El Husseiny, T.; Nassar, S.A.; Mohsen, R.A.; Alaa, D.; Allah, S.H.G.; Bakry, A.; Refaat, R.; et al. Ultrasound findings of adenomyosis in adolescents: Type and grade of the disease. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2022, 29, 291–299.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.; Shams, M.; Badawy, A.; Alsammani, M.A. Prevalence of endometriosis among adolescent school girls with severe dysmenorrhea: A cross-sectional prospective study. Int. J. Health Sci. 2015, 9, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, P.; Gupta, S.; Gieg, S. Endometriosis in adolescents: A systematic review. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2017, 9, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiVasta, A.D.; Vitonis, A.F.; Laufer, M.R.; Missmer, S.A. Spectrum of symptoms in women diagnosed with endometriosis during adolescence vs adulthood. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 324.e1–324.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, J.S.; DiVasta, A.D.; Vitonis, A.F.; Sarda, V.; Laufer, M.R.; Missmer, S.A. The impact of endometriosis on quality of life in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Echevarría, A.M.; Rosario, E.; Acevedo, S.; Flores, I. Impact of coping strategies on quality of life of adolescents and young women with endometriosis. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 40, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannoni, L.; Giorgi, M.; Spagnolo, E.; Montanari, G.; Villa, G.; Seracchioli, R. Dysmenorrhea, absenteeism from school, and symptoms suspicious for endometriosis in adolescents. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2014, 27, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandek, B.; Ware, J.E.; Aaronson, N.K.; Apolone, G.; Bjorner, J.B.; Brazier, J.E.; Bullinger, M.; Kaasa, S.; Leplege, A.; Prieto, L.; et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, I.; Belloni, G.M.; Barbera, V.; Solima, E.; Radice, D.; Angioni, S.; Bergamini, V.; Candiani, M.; Maiorana, A.; Mattei, A.; et al. “Better late than never but never late is better”, especially in young women: A multicenter Italian study on diagnostic delay for symptomatic endometriosis. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2023, 28, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.Y.; Laufer, M.R.; King, C.R.; Lee TT, M.; Einarsson, J.I.; Tyson, N. Evaluation and management of endometriosis in the adolescent. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 143, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 760: Dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in the adolescent. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, e249–e258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsonis, O.; Barmpalia, Z.; Gkrozou, F.; Chandraharan, E.; Pandey, S.; Siafaka, V.; Paschopoulos, M. Endometriosis in adolescence: Early manifestation of the traditional disease or a unique variant? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 247, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manganaro, L.; Vittori, G.; Vinci, V.; Fierro, F.; Tomei, A.; Lodise, P.; Sollazzo, P.; Sergi, M.E.; Bernardo, S.; Ballesio, L.; et al. Beyond laparoscopy: 3-T magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of posterior cul-de-sac obliteration. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 30, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celli, V.; Ciulla, S.; Dolciami, M.; Satta, S.; Ercolani, G.; Porpora, M.G.; Catalano, C.; Manganaro, L. Magnetic resonance imaging in endometriosis-associated pain. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 73, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porpora, M.G.; Scaramuzzino, S.; Sangiuliano, C.; Piacenti, I.; Bonanni, V.; Piccioni, M.G.; Ostuni, R.; Masciullo, L.; Panici, P.L.B. High prevalence of autoimmune diseases in women with endometriosis: A case-control study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2020, 36, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; Correia, K.F.; Vitonis, A.F.; Missmer, S.A. Body size and endometriosis: Results from 20 years of follow-up within the Nurses’ Health Study II prospective cohort. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 1783–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosens, I.; Gargett, C.E.; Guo, S.W.; Puttemans, P.; Gordts, S.; Brosens, J.J.; Benagiano, G. Origins and progression of adolescent endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2016, 23, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smorgick, N.; As-Sanie, S.; Marsh, C.A.; Smith, Y.R.; Quint, E.H. Advanced stage endometriosis in adolescents and young women. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2014, 27, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaskoff, M.; Bijon, A.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Mesrine, S.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C. Childhood and adolescent exposures and the risk of endometriosis. Epidemiology 2013, 24, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.M.; Mechsner, S. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: The origin of pain and subfertility. Cells 2021, 10, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieberg, C.B.; Lunde, C.E.; Borsook, D. Endometriosis and pain in the adolescent: Striking early to limit suffering: A narrative review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 108, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.A.; Missmer, S.A.; Vitonis, A.F.; Sarda, V.; Laufer, M.R.; DiVasta, A.D. Prevalence of migraines in adolescents with endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladosu, F.A.; Tu, F.F.; Hellman, K.M. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug resistance in dysmenorrhea: Epidemiology, causes, and treatment. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, N.; Kasap, B.; Kirli, U.; Yeniceri, N.; Topal, Y. Assessment of anxiety-depression levels and perceptions of quality of life in adolescents with dysmenorrhea. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piacenti, I.; Viscardi, M.F.; Masciullo, L.; Sangiuliano, C.; Scaramuzzino, S.; Piccioni, M.G.; Ludovico, M.; Porpora, M.G. Dienogest versus continuous oral levonorgestrel/EE in patients with endometriosis: What’s the best choice? Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayade, S.; Rai, S.; Pai, H.; Patel, M.; Makhija, N. Efficacy of dienogest in adolescent endometriosis: A narrative review. Cureus 2023, 15, e36729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).