Suicide in Italy: Epidemiological Trends, Contributing Factors, and the Forensic Pathologist’s Role in Prevention and Investigation

Abstract

1. Understanding the Suicide: Analysis of Risk Factors

2. The Suicidal Process: From Ideation to Action

3. Material and Methods

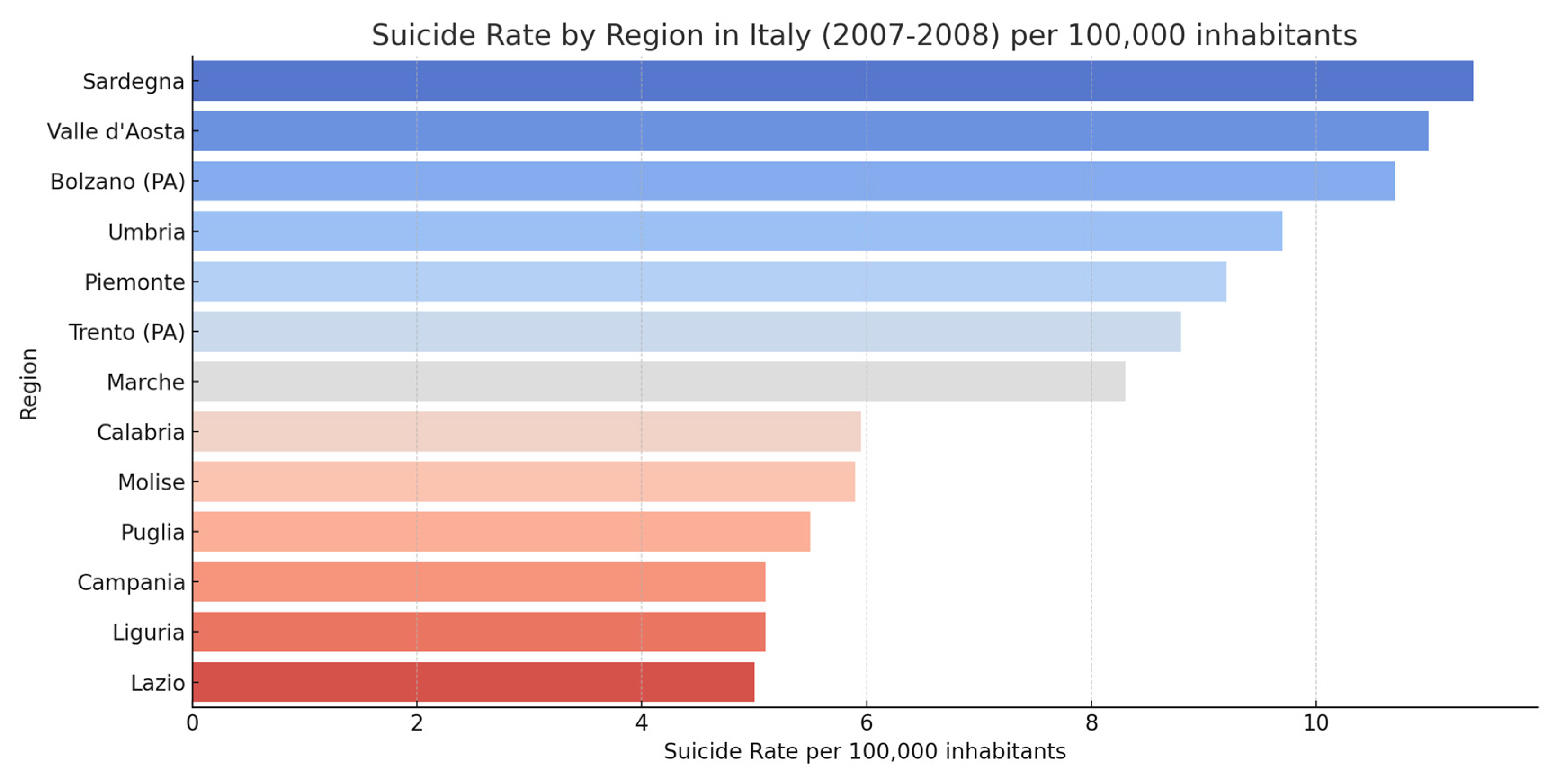

4. Epidemiology of Suicide: A Global and Local Perspective in Italy

5. The Role of Forensic Medicine: A Multidimensional Perspective and Italian Data

5.1. The Importance of Forensic Medicine in Suicide Analysis

5.2. Evaluation of Suicide Statistics in Italy

5.3. The Role of Linguistics

6. The Synergy Between Forensic Medicine and Psychiatry

7. The Suicide Among Cisgender, Transgender, and Intersex People

8. Psychological Autopsy: A Tool for Understanding Suicide

Suicide Notes: Understanding the Final Messages

9. Conclusions: Forensic Medicine’s Contribution to Suicide Understanding and Prevention

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sher, L.; Oquendo, M.A. Suicide: An Overview for Clinicians. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 107, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, J. Suicidality in Borderline Personality Disorder. Medicine 2019, 55, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruggieri, V. Autism, depresión y riesgo de suicida [Autism, depression and risk of suicide]. Medicine 2020, 80 (Suppl. S2), 12–16. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rihmer, Z.; Rihmer, A. Depression and suicide—The role of underlying bipolarity. Psychiatr. Hung. 2019, 34, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ehlers, C.L.; Yehuda, R.; Gilder, D.A.; Bernert, R.; Karriker-Jaffe, K.J. Trauma, historical trauma, PTSD and suicide in an American Indian community sample. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 156, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- D’Anci, K.E.; Uhl, S.; Giradi, G.; Martin, C. Treatments for the Prevention and Management of Suicide: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.J.; Apter, A.; Bertolote, J.; Beautrais, A.; Currier, D.; Haas, A.; Hegerl, U.; Lonnqvist, J.; Malone, K.; Marusic, A.; et al. Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review. JAMA 2005, 294, 2064–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmani, A.; Rahimianbougar, M.; Mohammadi, Y.; Faramarzi, H.; Khodarahimi, S.; Nahaboo, S. Psychological, Structural, Social and Economic Determinants of Suicide Attempt: Risk Assessment and Decision Making Strategies. Omega 2023, 86, 1144–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, K.L.; Jacobson, S.V.; Ton, A.T.; Law, K.C. Association between race and socioeconomic factors and suicide-related 911 call rate. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 306, 115106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girardi, P.; Boldrini, T.; Braggion, M.; Schievano, E.; Amaddeo, F.; Fedeli, U. Suicide mortality among psychiatric patients in Northeast Italy: A 10-year cohort study. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schneider, B. Substance use disorders and risk for completed suicide. Arch. Suicide Res. 2009, 13, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, L.F.; Glass, T.; Brissette, I.; Seeman, T.E. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M. The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A New Theory of Suicide Rooted in the “Ideation-to-Action” Framework. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2015, 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, T.E. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E., Jr. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Kirtley, O.J. The Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicidal Behaviour. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, J.D.; Franklin, J.C.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors as Risk Factors for Future Suicide Ideation, Attempts, and Death: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M.K.; Borges, G.; Bromet, E.J.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; Beautrais, A.; Bruffaerts, R.; Chiu, W.T.; De Girolamo, G.; Gluzman, S.; et al. Cross-National Prevalence and Risk Factors for Suicidal Ideation, Plans and Attempts. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 192, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.M.; Klonsky, E.D. What Distinguishes Suicide Attempters from Suicide Ideators? A Meta-Analysis of Potential Factors. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2016, 23, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, J.C.; Ribeiro, J.D.; Fox, K.R.; Bentley, K.H.; Kleiman, E.M.; Huang, X.; Musacchio, K.M.; Jaroszewski, A.C.; Chang, B.P.; Nock, M.K. Risk Factors for Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 187–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Rudd, M.D. Advances in the Assessment of Suicide Risk. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Buchman-Schmitt, J.M.; Stanley, I.H.; Hom, M.A.; Tucker, R.P.; Hagan, C.R.; Rogers, M.L.; Podlogar, M.C.; Chiurliza, B.; Ringer, F.B.; et al. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of a Decade of Cross-National Research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 1313–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenn, C.R.; Nock, M.K. Improving the Short-Term Prediction of Suicidal Behavior. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 47, S176–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Borges, G.; Nock, M.; Wang, P.S. Trends in Suicide Ideation, Plans, Gestures, and Attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA 2005, 293, 2487–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posner, K.; Brown, G.K.; Stanley, B.; Brent, D.A.; Yershova, K.V.; Oquendo, M.A.; Currier, G.W.; Melvin, G.A.; Greenhill, L.; Shen, S.; et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings from Three Multisite Studies with Adolescents and Adults. Am. J. Psychiatry 2011, 168, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; van Heeringen, K. Suicide. Lancet 2009, 373, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schienle, A.; Schwab, D.; Höfler, C.; Freudenthaler, H.H. Self-Disgust and Its Relationship with Lifetime Suicidal Ideation and Behavior. Crisis 2020, 41, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarti, S.; Vitalini, A. The health of Italians before and after the economic crisis of 2008. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, E.; Grippo, F.; Crialesi, R.; Marchetti, S.; Frova, L. Suicide mortality in Italy during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (ISTAT). Suicidi e Tentativi di Suicidio in Italia; ISTAT: Rome, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/226455 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- De Vogli, R.; Marmot, M.; Stuckler, D. Excess Suicides and Attempted Suicides in Italy Attributable to the Great Recession. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 378–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.K.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, S.Y.; Moon, J.; Jeon, D.W.; Shim, S.H.; Cho, S.J.; Kim, S.G.; Lee, J.; Paik, J.W.; et al. Suicide risk factors across suicidal ideators, single suicide attempters, and multiple suicide attempters. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 131, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Hou, J.; Li, Q.; Yu, N.X. Suicide before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Osservatorio Medicina di Genere. Il Suicidio in Italia. Epidemiologia, Fattori di Rischio e Strategie di Prevenzione con un Approccio Sex and Gender Based. Available online: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/6744472/IL+SUICIDIO+IN+ITALIA.+Epidemiologia,+fattori+di+rischio+e+strategie+di+prevenzione+con+un+approccio+sex+and+gender+based.pdf/bf8157e0-5605-7584-9ca2-d95d4e54f591?t=1666776546607 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Merzagora, I.; Travaini, G.; Barbieri, C.; Caruso, P.; Ciappi, S. The psychological autopsy: Contradictio in adiecto? Rass. Ital. Di Criminol. 2017, 11, 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bonicatto, B.; Perez, T.G.; Lòpez, R.R. L’autopsia Psicologica L’indagine nei casi di Morte Violenta o Dubbia; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, T.P.; Yip, P.S.; Chiu, C.W.; Halliday, P. Suicide notes: What do they tell us? Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1998, 98, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Räder, K.K.; Adler, L.; Freisleder, F.J. Zur Differenzierung von Suizid und Parasuizid. Eine Untersuchung an Abschiedsbriefen suicidal Patienten [Differentiation of suicide and parasuicide. A study of the last letters of suicidal patients]. Schweiz Arch Neurol Psychiatr (1985) 1991, 142, 439–450. (In German) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaur, S.; Satapathy, S.; Kaushik, R.; Sikary, A.K.; Behera, C. A multifaceted expression study of audio-visual suicide notes. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2020, 54, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejías-Martín, Y.; Martí-García, C.; Rodríguez-Mejías, Y.; Esteban-Burgos, A.A.; Cruz-García, V.; García-Caro, M.P. Understanding for Prevention: Qualitative and Quantitative Analyzes of Suicide Notes and Forensic Reports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Freuchen, A.; Grøholt, B. Characteristics of suicide notes of children and young adolescents: An examination of the notes from suicide victims 15 years and younger. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eynan, R.; Shah, R.; Heisel, M.J.; Eden, D.; Jhirad, R.; Links, P.S. Last Words: Are There Differences in Psychosocial and Clinical Antecedents Among Suicide Decedants Who Leave E-Notes, Paper Notes, or No Notes? Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 1379–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Khan, M.M.; Menon, V.; Ali, S.A.; Rezaeian, M.; Shoib, S. Psychological autopsy study and risk factors for suicide in Muslim countries. Health Sci. Rep. 2021, 4, e414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Menon, V.; Varadharajan, N.; Kar, S.K. Psychological Autopsy Studies of Suicide in South East Asia. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2022, 44, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plöderl, M.; Tremblay, P. Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2015, 27, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toomey, R.B.; Syvertsen, A.K.; Shramko, M. Transgender Adolescent Suicide Behavior. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20174218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salway, T.; Ross, L.E.; Fehr, C.P.; Burley, J.; Asadi, S.; Hawkins, B.; Tarasoff, L.A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Disparities in the Prevalence of Suicide Ideation and Attempt Among Bisexual Populations. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshal, M.P.; Dietz, L.J.; Friedman, M.S.; Stall, R.; Smith, H.A.; McGinley, J.; Thoma, B.C.; Murray, P.J.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Brent, D.A. Suicidality and Depression Disparities Between Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonicatto, B.; Garcia Pèrez, T.; Rojas Lòpez, R. L’autopsia Psicologica; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, D.; Yadav, J.; Rozatkar, A.R.; Moirangthem, S.; Arora, A. The psychological autopsy: An overview of its utility and methodology. J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2023, 14, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A.P.; Eliason, M.; Mays, V.M.; Mathy, R.M.; Cochran, S.D.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Silverman, M.M.; Fisher, P.W.; Hughes, T.; Rosario, M.; et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. J. Homosex. 2011, 58, 10–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Acocella, I.; Cellini, E. Il Suicidio di Émile Durkheim: Un esempio di analisi multivariata. Quad. Di Sociol. 2011, 55, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Total Suicides (2020–2021) | 7422 recorded suicides |

| Gender Distribution (2020–2021) | 76.8% male, 23.2% female |

| Most Common Methods (Male) | Hanging (52.2%), Falling (15.8%), Firearms (13.7%) |

| Most Common Methods (Female) | Hanging (34.8%), Falling (31.9%), Drowning (8.0%) |

| Regions with Highest Rates | Northern Italy (particularly North-East regions) |

| Age Group with Highest Rates (Male) | ≥70 years old |

| Age Group with Highest Rates (Female) | ≥70 years old |

| Impact of COVID-19 | Overall reduction in suicides (−2.8% males, −7.7% females); slight increase in elderly males and females ≥ 85 years |

| Key Associated Comorbidities | Depression, anxiety, physical illnesses (e.g., chronic conditions) |

| Percentage of Cases with Suicide Notes | 25–30% of cases include notes (varies by demographic) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gualtieri, S.; Lombardo, S.; Sacco, M.A.; Verrina, M.C.; Tarallo, A.P.; Carbone, A.; Costa, A.; Aquila, I. Suicide in Italy: Epidemiological Trends, Contributing Factors, and the Forensic Pathologist’s Role in Prevention and Investigation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041186

Gualtieri S, Lombardo S, Sacco MA, Verrina MC, Tarallo AP, Carbone A, Costa A, Aquila I. Suicide in Italy: Epidemiological Trends, Contributing Factors, and the Forensic Pathologist’s Role in Prevention and Investigation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(4):1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041186

Chicago/Turabian StyleGualtieri, Saverio, Stefano Lombardo, Matteo Antonio Sacco, Maria Cristina Verrina, Alessandro Pasquale Tarallo, Angela Carbone, Andrea Costa, and Isabella Aquila. 2025. "Suicide in Italy: Epidemiological Trends, Contributing Factors, and the Forensic Pathologist’s Role in Prevention and Investigation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 4: 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041186

APA StyleGualtieri, S., Lombardo, S., Sacco, M. A., Verrina, M. C., Tarallo, A. P., Carbone, A., Costa, A., & Aquila, I. (2025). Suicide in Italy: Epidemiological Trends, Contributing Factors, and the Forensic Pathologist’s Role in Prevention and Investigation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(4), 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041186