Clinical Ascites and Emergency Procedure as Determinants of Surgical Risk in Patients with Advanced Chronic Liver Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Variables and Definitions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients

3.2. Hospital Stay and Liver-Related Events After Surgery

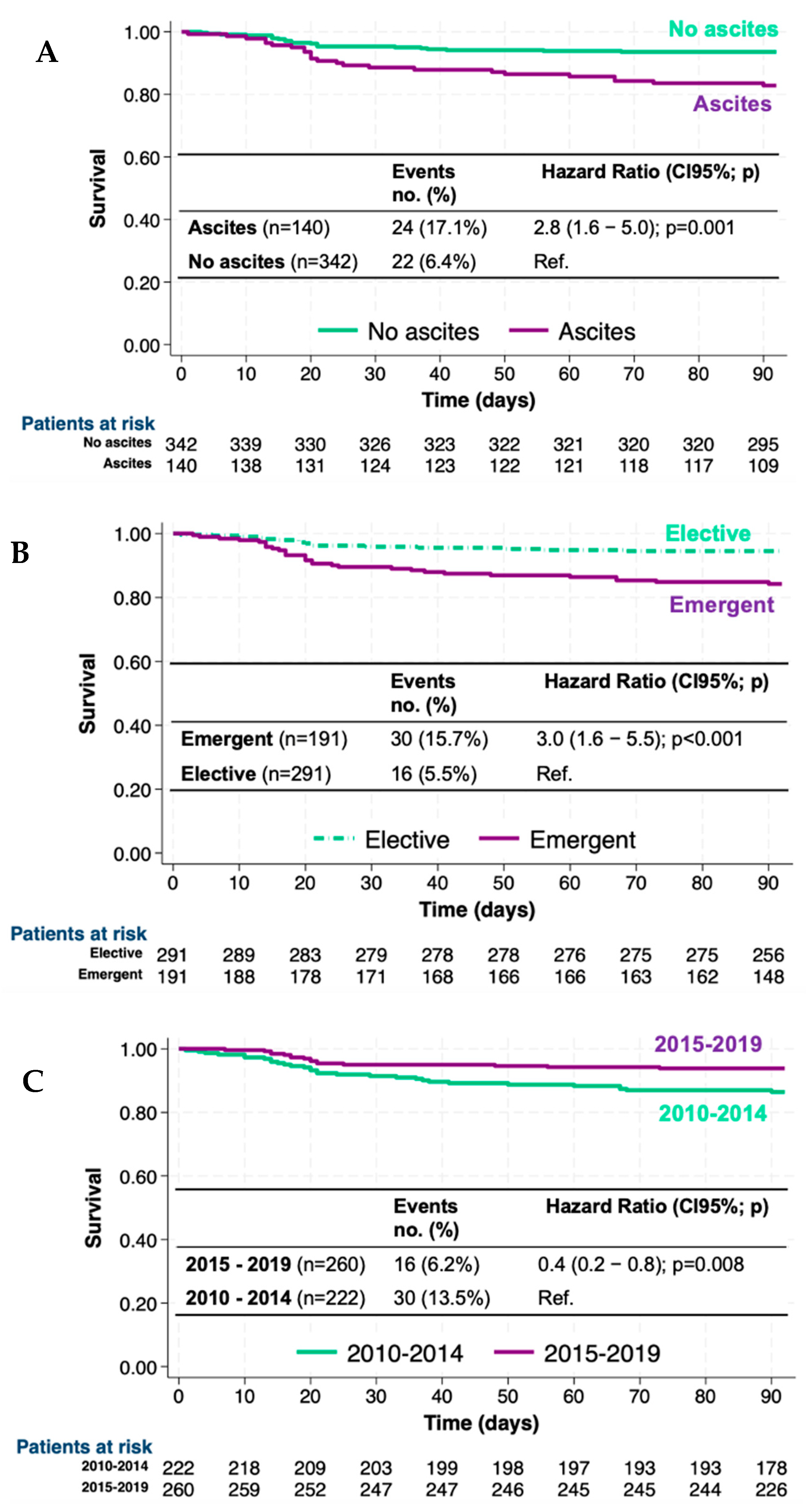

3.3. Mortality Risk and Survival

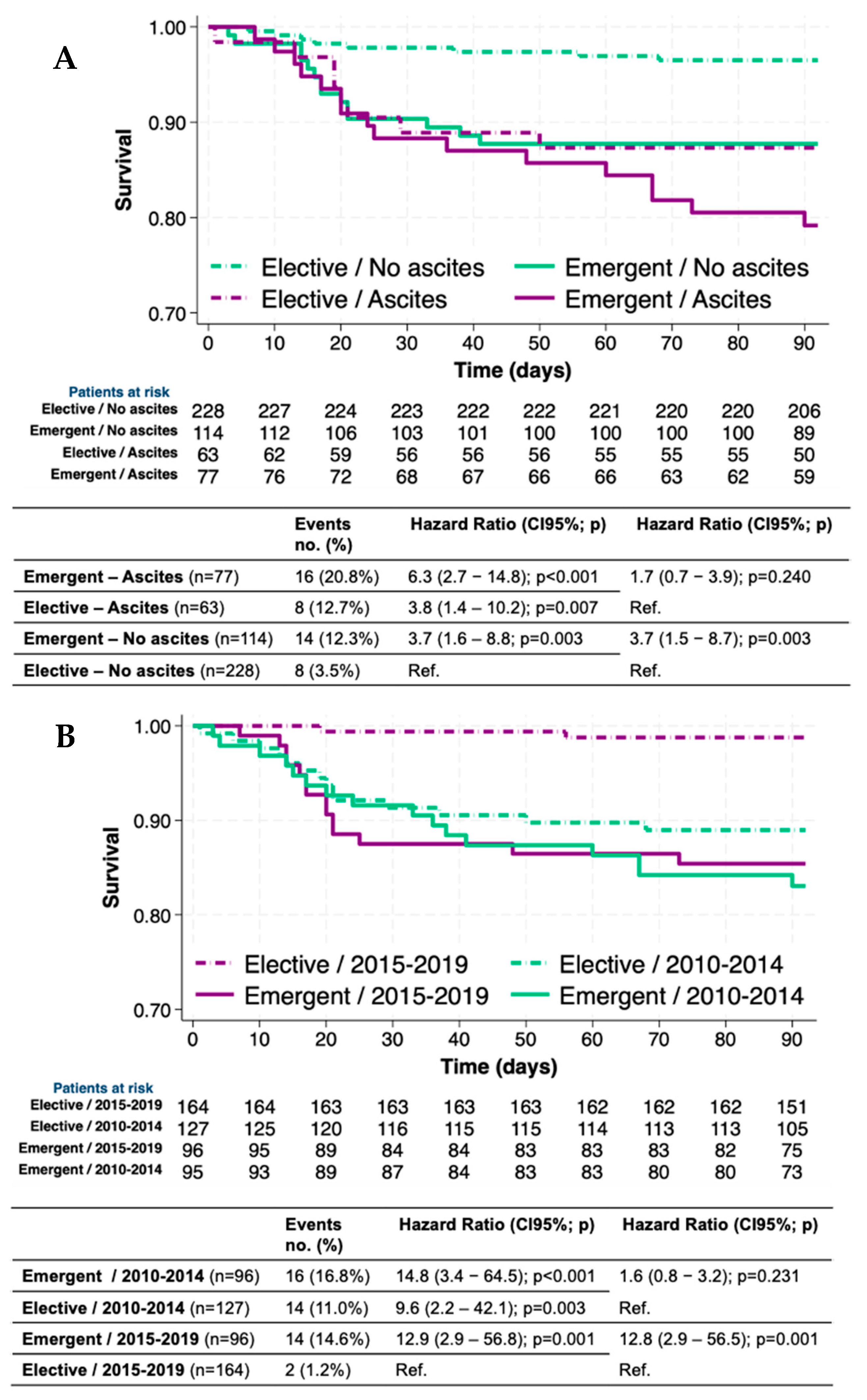

3.4. Survival and Mortality Risk in Different Groups of Patients, Surgeries, and Periods

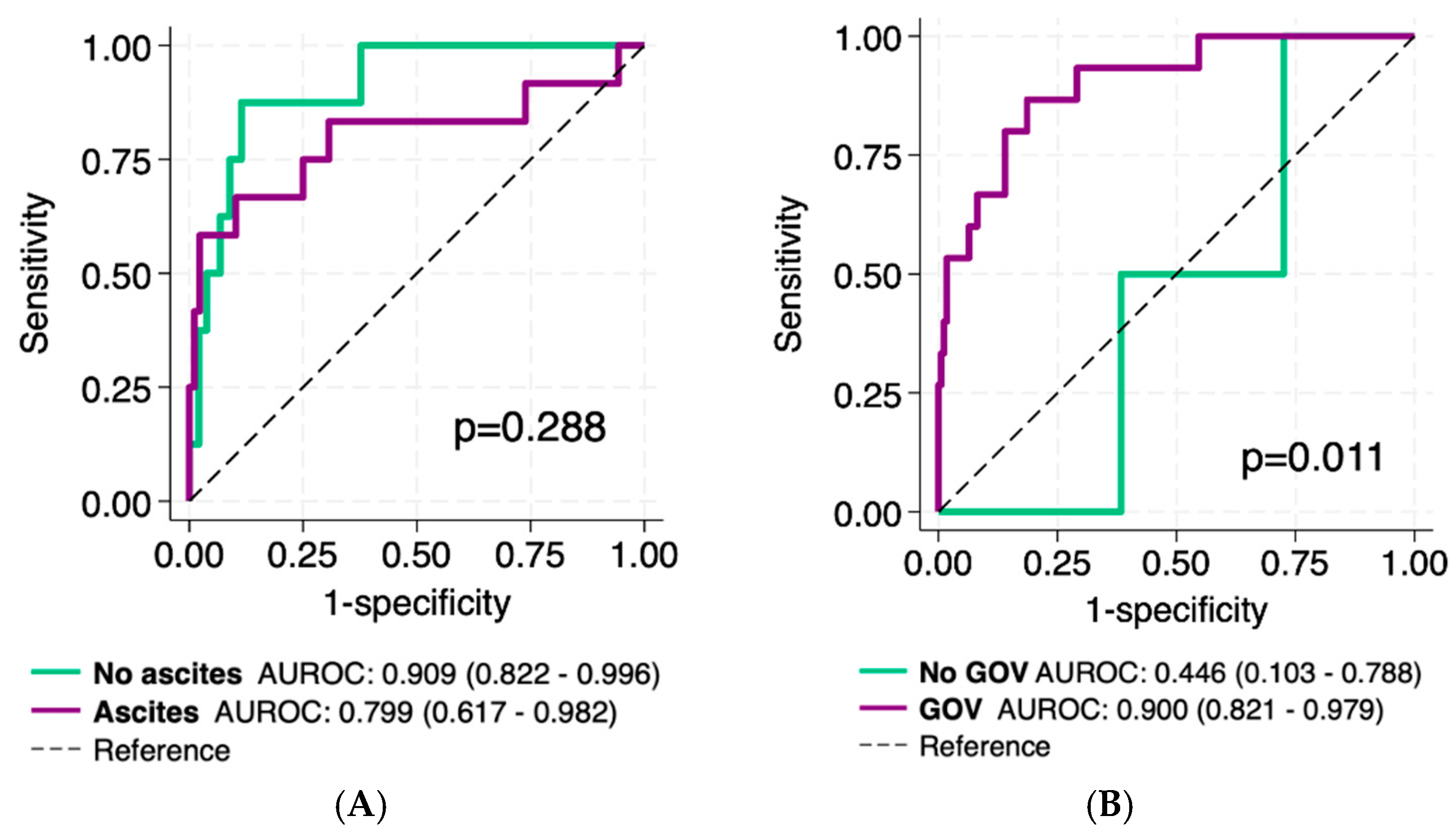

3.5. VOCAL-Penn Diagnostic Accuracy in Patients with Portal Hypertension

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D’Amico, G.; Morabito, A.; D’Amico, M.; Pasta, L.; Malizia, G.; Rebora, P.; Valsecchi, M.G. Clinical states of cirrhosis and competing risks. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, K.L.; Johnson, K.M.; Cornia, P.B.; Wu, P.; Itani, K.; Ioannou, G.N. Perioperative Evaluation and Management of Patients With Cirrhosis: Risk Assessment, Surgical Outcomes, and Future Directions. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2398–2414 e2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, N.; Fricker, Z.; Lewis, J.D.; Taddei, T.H.; Goldberg, D.S.; Kaplan, D.E. Risk Prediction Models for Postoperative Decompensation and Infection in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Veterans Affairs Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, e1121–e1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canillas, L.; Pelegrina, A.; Colominas-Gonzalez, E.; Salis, A.; Enriquez-Rodriguez, C.J.; Duran, X.; Caro, A.; Alvarez, J.; Carrion, J.A. Comparison of Surgical Risk Scores in a European Cohort of Patients with Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reverter, E.; Cirera, I.; Albillos, A.; Debernardi-Venon, W.; Abraldes, J.G.; Llop, E.; Flores, A.; Martinez-Palli, G.; Blasi, A.; Martinez, J.; et al. The prognostic role of hepatic venous pressure gradient in cirrhotic patients undergoing elective extrahepatic surgery. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Olmo, J.A.; Flor-Lorente, B.; Flor-Civera, B.; Rodriguez, F.; Serra, M.A.; Escudero, A.; Lledo, S.; Rodrigo, J.M. Risk factors for nonhepatic surgery in patients with cirrhosis. World J. Surg. 2003, 27, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telem, D.A.; Schiano, T.; Goldstone, R.; Han, D.K.; Buch, K.E.; Chin, E.H.; Nguyen, S.Q.; Divino, C.M. Factors that predict the outcome of abdominal operations in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 8, 451–457, quiz e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, K.A.; Hjortnaes, J.; Kranenburg, G.; de Heer, F.; Kluin, J. Mortality after cardiac surgery in patients with liver cirrhosis classified by the Child-Pugh score. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 20, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northup, P.G.; Wanamaker, R.C.; Lee, V.D.; Adams, R.B.; Berg, C.L. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) predicts nontransplant surgical mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Ann. Surg. 2005, 242, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, S.H.; Nagorney, D.M.; Stevens, S.R.; Offord, K.P.; Therneau, T.M.; Plevak, D.J.; Talwalkar, J.A.; Kim, W.R.; Kamath, P.S. Risk factors for mortality after surgery in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N.; Fallowfield, J.; Patch, D.; Stanley, A.J.; Mookerjee, R.; Tsochatzis, E.; Leithead, J.A.; Hayes, P.; Chauhan, A.; Sharma, V.; et al. Guidance document: Risk assessment of patients with cirrhosis prior to elective non-hepatic surgery. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, N.; Fricker, Z.; Serper, M.; Kaplan, D.E.; Rothstein, K.D.; Goldberg, D.S. In-Hospital mortality varies by procedure type among cirrhosis surgery admissions. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 1394–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridola, L.; Del Cioppo, S. Advancing hepatic recompensation: Baveno VII criteria and therapeutic innovations in liver cirrhosis management. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 2954–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, C.; Albillos, A.; Genesca, J.; Garcia-Pagan, J.C.; Calleja, J.L.; Aracil, C.; Banares, R.; Morillas, R.M.; Poca, M.; Penas, B.; et al. beta blockers to prevent decompensation of cirrhosis in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension (PREDESCI): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1597–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, C.; Torres, F.; Sarin, S.K.; Shah, H.A.; Tripathi, D.; Brujats, A.; Rodrigues, S.G.; Bhardwaj, A.; Azam, Z.; Hayes, P.C.; et al. Carvedilol reduces the risk of decompensation and mortality in patients with compensated cirrhosis in a competing-risk meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, N.; Fricker, Z.; Hubbard, R.A.; Ioannou, G.N.; Lewis, J.D.; Taddei, T.H.; Rothstein, K.D.; Serper, M.; Goldberg, D.S.; Kaplan, D.E. Risk Prediction Models for Post-Operative Mortality in Patients With Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2021, 73, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilimoria, K.Y.; Liu, Y.; Paruch, J.L.; Zhou, L.; Kmiecik, T.E.; Ko, C.Y.; Cohen, M.E. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: A decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013, 217, 833–842 e831-833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrion, J.A.; Puigvehi, M.; Coll, S.; Garcia-Retortillo, M.; Canete, N.; Fernandez, R.; Marquez, C.; Gimenez, M.D.; Garcia, M.; Bory, F.; et al. Applicability and accuracy improvement of transient elastography using the M and XL probes by experienced operators. J. Viral Hepat. 2015, 22, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gines, P.; Krag, A.; Abraldes, J.G.; Sola, E.; Fabrellas, N.; Kamath, P.S. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2021, 398, 1359–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surlin, V. Emergency and Trauma Surgery. Chirurgia 2021, 116, 643–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, P.; Gines, P.; Wong, F.; Bernardi, M.; Boyer, T.D.; Gerbes, A.; Moreau, R.; Jalan, R.; Sarin, S.K.; Piano, S.; et al. Diagnosis and management of acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: Revised consensus recommendations of the International Club of Ascites. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canillas, L.; Pelegrina, A.; Alvarez, J.; Colominas-Gonzalez, E.; Salar, A.; Aguilera, L.; Burdio, F.; Montes, A.; Grau, S.; Grande, L.; et al. Clinical Guideline on Perioperative Management of Patients with Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. Life 2023, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronswijk, M.; Jaekers, J.; Vanella, G.; Struyve, M.; Miserez, M.; van der Merwe, S. Umbilical hernia repair in patients with cirrhosis: Who, when and how to treat. Hernia 2022, 26, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, H.H.; van Ramshorst, G.H.; de Goede, B.; Tilanus, H.W.; Metselaar, H.J.; de Man, R.A.; Lange, J.F.; Kazemier, G. A prospective study on elective umbilical hernia repair in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites. Surgery 2011, 150, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Goede, B.; van Rooijen, M.M.J.; van Kempen, B.J.H.; Polak, W.G.; de Man, R.A.; Taimr, P.; Lange, J.F.; Metselaar, H.J.; Kazemier, G. Conservative treatment versus elective repair of umbilical hernia in patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites: Results of a randomized controlled trial (CRUCIAL trial). Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northup, P.G.; Friedman, L.S.; Kamath, P.S. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Surgical Risk Assessment and Perioperative Management in Cirrhosis: Expert Review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canillas, L.; Pelegrina, A.; Alvarez, J.; Carrion, J.A. Portal hypertension or histologic characteristics of the liver? J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 29, 101881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All patients (n = 482) | No ascites (n = 342) | Ascites (n = 140) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 66 (57–75) | 66 (56–76) | 66 (58–75) | 0.744 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 318 (66.0) | 224 (65.5) | 94 (67.1) | 0.846 |

| ASA, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| II | 61 (12.7) | 61 (17.8) | 0 (0) | |

| III | 348 (72.2) | 248 (72.5) | 100 (71.4) | |

| IV | 73 (15.2) | 33 (9.7) | 40 (28.6) | |

| Etiology of liver disease, n (%) | ||||

| Viral | 159 (33.0) | 124 (36.3) | 35 (25.0) | 0.011 |

| Alcohol | 244 (50.6) | 158 (46.2) | 86 (61.4) | 0.003 |

| MASLD | 54 (11.2) | 41 (12.0) | 13 (9.3) | 0.393 |

| Other | 25 (5.2) | 19 (5.6) | 6 (4.3) | 0.749 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) (n = 481) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.432 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) (n = 436) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.7 (0.5–1.2) | 1.1 (0.8–2.1) | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) (n = 429) | 4.0 (3.2–4.3) | 4.2 (3.6–4.4) | 3.3 (2.7–3.9) | <0.001 |

| INR (n = 481) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count (× 103/uL) | 129 (92–187) | 137 (99–192) | 110 (80–170) | <0.001 |

| MELD-Na (n = 436) | 12 (8–16) | 11 (8–14) | 14 (10–20) | <0.001 |

| CTP class, n (%) (n = 420) | ||||

| A | 285 (70.2) | 245 (88.8) | 40 (30.8) | <0.001 |

| B | 96 (23.7) | 30 (10.9) | 66 (50.8) | |

| C | 25 (6.2) | 1 (0.4) | 24 (18.5) | |

| LSM (kPa) (n = 197) | 15.7 (11.2–23.6) | 15.7 (11.2–23.6) | − | − |

| Splenomegaly + thrombocytopenia (n = 475) | 190 (40.0) | 115 (34.0) | 75 (54.7) | <0.001 |

| GOV, n (%) (n = 403) | 245 (60.8) | 145 (52.7) | 100 (78.1) | <0.001 |

| Surgery information | ||||

| Type of surgery, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| Abdominal | 197 (40.9) | 155 (45.3) | 42 (30.0) | |

| Non-abdominal | 285 (59.1) | 187 (54.7) | 98 (70.0) | |

| Emergent surgery, n (%) | 191 (39.6) | 114 (33.3) | 77 (55.0) | <0.001 |

| Oncologic surgery, n (%) | 62 (12.9) | 52 (15.2) | 10 (7.1) | 0.016 |

| Period of surgery, n (%) | 0.189 | |||

| 2010–2014 | 232 (47.0) | 151 (44.2) | 71 (50.7) | |

| 2015–2019 | 262 (53.0) | 191 (55.9) | 69 (49.3) | |

| VOCAL-Penn’s 30-day predicted mortality (%) | 1.2 (0.3–4.3) | 0.6 (0.2–2.5) | 4.5 (1.4–10.1) | <0.001 |

| Events and mortality at 90 days | ||||

| AKI, n (%) (n = 446) | 148 (33.2) | 84 (27.0) | 64 (47.4) | <0.001 |

| AKI-1A | 37 (8.3) | 23 (7.4) | 14 (10.4) | <0.001 |

| AKI-1B | 42 (9.4) | 28 (9.0) | 14 (10.4) | |

| AKI-2 | 35 (7.8) | 16 (5.1) | 19 (14.1) | |

| AKI-3 | 34 (6.3) | 17 (5.5) | 17 (12.6) | |

| Ascites, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Worsening | 23 (4.8) | - | 23 (16.4) | - |

| New-onset ascites | 65 (14.5) | 65 (19.0) | - | - |

| Improvement | 27 (5.6) | - | 27 (19.3) | - |

| Other first hepatic decompensation, n (%) | 15 (3.1) | 6 (1.8) | 9 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Bacterial peritonitis, n (%) | 53 (11.0) | 21 (6.1) | 32 (22.9) | <0.001 |

| Any LREs, n (%) | 160 (33.2) | 71 (20.8) | 89 (63.6) | <0.001 |

| Death, n (%) | 46 (9.5) | 22 (6.4) | 24 (17.1) | <0.001 |

| Elective (n = 291) | Emergent (n = 191) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 67 (57–74) | 65 (55–78) | 0.896 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 190 (65.3) | 128 (67.2) | 0.696 |

| ASA, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| II | 39 (13.4) | 22 (11.5) | |

| III | 224 (77.0) | 124 (64.9) | |

| IV | 28 (9.6) | 45 (23.6) | |

| Etiology of liver disease, n (%) | |||

| Viral | 98 (33.7) | 61 (31.9) | 0.474 |

| Alcohol | 137 (47.1) | 107 (56.0) | 0.035 |

| MASLD | 37 (12.7) | 17 (8.9) | 0.194 |

| Other | 18 (6.5) | 6 (3.1) | 0.174 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) (n = 481) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.460 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) (n = 436) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) (n = 429) | 4.1 (3.5–4.5) | 3.5 (2.9–4.1) | <0.001 |

| INR (n = 481) | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count (×103/uL) | 134 (100–189) | 114 (84–183) | 0.010 |

| MELD-Na (n = 436) | 10 (8–14) | 14 (11–19) | <0.001 |

| CTP, n (%) (n = 406) | |||

| A | 202 (80.5) | 83 (53.6) | <0.001 |

| B | 42 (16.7) | 54 (34.8) | |

| C | 7 (2.8) | 18 (11.6) | |

| Ascites 30 days before surgery, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Grade 2 | 41 (14.1) | 27 (14.1) | |

| Grade 3 | 22 (7.6) | 50 (26.2) | |

| LSM (kPa) (n = 197) | 15.5 (11.2–23.4) | 15.9 (11.5–25.5) | 0.984 |

| Splenomegaly + thrombocytopenia (n = 475) | 113 (39.7) | 77 (40.5) | 0.848 |

| GOV, n (%) (n = 403) | 143 (58.4) | 102 (64.6) | 0.214 |

| Surgery information | |||

| Type of surgery, n (%) | 0.091 | ||

| Abdominal | 110 (37.8) | 104 (54.5) | |

| Non-abdominal | 181 (62.2) | 87 (45.5) | |

| Oncologic surgery, n (%) | 56 (19.2) | 6 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Period of surgery, n (%) | 0.189 | ||

| 2010–2014 | 127 (43.6) | 95 (49.7) | |

| 2015–2019 | 164 (56.4) | 96 (50.3) | |

| VOCAL-Penn’s 30-day predicted mortality (%) | 0.5 (0.2–2.0) | 3.6 (1.4–11.0) | <0.001 |

| Events and death at 90 days | |||

| AKI, n (%) (N = 446) | 63 (24.2) | 85 (45.7) | <0.001 |

| AKI-1A | 15 (5.8) | 22 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| AKI-1B | 19 (7.3) | 23 (12.4) | |

| AKI-2 | 18 (6.9) | 17 (9.1) | |

| AKI-3 | 11 (4.2) | 23 (12.4) | |

| Ascites, n (%) | |||

| Worsening | 9 (3.1) | 14 (7.3) | 0.033 |

| New-onset ascites | 25 (8.6) | 40 (20.9) | <0.001 |

| Improvement | 18 (6.2) | 9 (4.7) | 0.491 |

| Other first hepatic decompensation, n (%) | 2 (0.7) | 13 (6.8) | <0.001 |

| Bacterial peritonitis, n (%) | 19 (6.5) | 34 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Any LREs, n (%) | 53 (18.2) | 107 (56.0) | <0.001 |

| Death, n (%) | 16 (5.5) | 30 (15.7) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Canillas, L.; Pelegrina, A.; León, F.W.; Salis, A.; Colominas-González, E.; Caro, A.; Sánchez, J.; Álvarez, J.; Burdio, F.; Carrión, J.A. Clinical Ascites and Emergency Procedure as Determinants of Surgical Risk in Patients with Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041077

Canillas L, Pelegrina A, León FW, Salis A, Colominas-González E, Caro A, Sánchez J, Álvarez J, Burdio F, Carrión JA. Clinical Ascites and Emergency Procedure as Determinants of Surgical Risk in Patients with Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(4):1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041077

Chicago/Turabian StyleCanillas, Lidia, Amalia Pelegrina, Fawaz Wasef León, Aina Salis, Elena Colominas-González, Antonia Caro, Juan Sánchez, Juan Álvarez, Fernando Burdio, and Jose A. Carrión. 2025. "Clinical Ascites and Emergency Procedure as Determinants of Surgical Risk in Patients with Advanced Chronic Liver Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 4: 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041077

APA StyleCanillas, L., Pelegrina, A., León, F. W., Salis, A., Colominas-González, E., Caro, A., Sánchez, J., Álvarez, J., Burdio, F., & Carrión, J. A. (2025). Clinical Ascites and Emergency Procedure as Determinants of Surgical Risk in Patients with Advanced Chronic Liver Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(4), 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14041077