Abstract

Background: Evidence on how everyday walking and sleep relate to mood in health profession students from Central–Eastern Europe remains limited. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study among 277 Romanian medical students. Data were collected using validated instruments for physical activity (IPAQ-SF), sleep quality (PSQI), and depressive/anxiety symptoms (HADS). Associations were examined using bivariate and multivariable regression models, including sex-stratified analyses. Results: In bivariate analysis, total physical activity was inversely correlated with depressive symptoms (ρ = −0.19, p < 0.001). However, in the multivariable model, this effect was not statistically significant after controlling for other factors. Poor sleep quality emerged as the dominant independent predictor of both depression (β = 0.37, p < 0.001) and anxiety (β = 0.40, p < 0.001). Walking time and frequency were specifically protective against depressive symptoms. Sex-stratified analyses revealed distinct patterns: female students benefited more from walking, whereas male students showed stronger associations between overall physical activity and lower depressive symptoms. Conclusions: Within the constraints of a cross-sectional design, this study provides novel evidence from Eastern Europe that sleep quality and physical activity are central to student mental health. Psychological benefits of walking appear sex-specific, and the null mediation finding suggests benefits operate via direct or unmodelled pathways. Sleep is a critical independent target for tailored, lifestyle-based strategies.

1. Introduction

Medical training is widely recognized as a demanding period associated with heightened psychological distress. Across diverse settings, medical students report substantial burdens of depressive symptoms, exceeding those observed in age-matched peers [1,2,3,4,5]. Multiple behavioral and psychosocial determinants have been implicated—including physical activity, sleep quality, and technology use—yet their relative contributions and interconnections remain incompletely understood, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe [1,2,6,7,8]. Clarifying which modifiable behaviors matter most, and for whom, is essential to inform targeted prevention within medical programs.

Physical activity (PA) is among the most consistent behavioral correlates of mental health. Observational syntheses and intervention trials indicate that higher habitual activity is associated with fewer depressive symptoms, and that structured exercise exerts small-to-moderate antidepressant effects [9,10,11]. The literature typically operationalizes PA at an aggregate level (e.g., total metabolic equivalent of task (MET)-min/week), which may obscure the contribution of light-intensity behaviors such as walking—an accessible, low-cost option that can be integrated into academic routines. Recent syntheses suggest that walking and higher daily step counts are associated with reduced depressive and anxiety symptoms [12,13], yet dedicated analyses in medical students remain scarce.

In parallel, sleep disturbance is highly prevalent among medical students and demonstrates robust associations with depression [14,15,16]. Conceptually, sleep may function as a mechanistic bridge linking activity patterns to mental health: regular activity improves sleep continuity and quality, whereas inadequate sleep impairs mood regulation and heightens negative affect [17,18,19]. A second candidate pathway frequently discussed in student populations is screen time/social media use, which may relate to sedentary behavior, circadian disruption, and internalizing symptoms; however, its explanatory value is modest and heterogeneous across studies [20,21].

A further determinant frequently examined is body mass index (BMI). While some population-based analyses describe a non-linear (U-shaped) association with depressive symptoms, the magnitude and consistency of BMI–mental health links in student cohorts are uncertain and may shrink once behavioral and psychosocial correlates are modeled [22,23]. Because medical students typically cluster within a narrow BMI range, studies may be underpowered to detect curvilinear effects; separating BMI from lifestyle covariates (sleep, activity) is therefore important. Additionally, potential sex differences warrant attention: women and men often engage in different activity profiles (e.g., walking vs. vigorous exercise) and may exhibit distinct psychological responses, implying value in sex-tailored recommendations [24,25].

Against this backdrop, there is a notable evidence gap in Romanian/Eastern European medical students integrating: (i) total physical activity and walking-specific metrics, (ii) sleep quality and screen time as candidate mediators, (iii) formal sex-stratified analyses, and (iv) explicit tests for BMI non-linearity alongside covariate adjustment. Addressing these gaps is timely for curriculum-level prevention strategies that are realistic to implement acknowledging the inherent limitation of causal inference within this cross-sectional framework.

To our knowledge, this is among the first studies from Central–Eastern Europe to jointly examine everyday walking, sleep quality, gaming time, and mood symptoms in health-professions students. By focusing on simple, scalable exposures (walking minutes; PSQI sleep quality), our findings offer context-specific evidence for a region that remains underrepresented in the literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study in Romanian medical students. All enrolled students who consented completed a standardized online survey that included anthropometrics, lifestyle, and validated psychometric instruments. Data collection for this study took place at the start of the fall semester of the 2024–2025 academic year. An online survey was administered to students using the PsyToolkit platform [26,27]. An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 [28,29] to determine the required sample size to detect a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) for our primary multivariable regression models, with a power of 0.80 and an alpha of 0.05. Given that our models included 9 predictors, this analysis indicated that a minimum sample size of 114 participants would be needed. The analytic sample comprised N = 277 students with complete outcome and exposure data for the primary analyses, which exceeded the a priori target and provided sufficient power to detect a small-to-medium effect.

The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and national regulations. Ethical approval was obtained from Galaţi College of Physicians (No. 1165/29.11.2024) and electronic informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Measures

- Anthropometrics

Participants self-reported weight (kg) and height (cm); BMI was computed as kg/m2. Values ≤ 12 kg/m2 were considered implausible and set to missing a priori. BMI was modeled continuously (kg/m2) and with a quadratic term (BMI2) to test non-linearity. For descriptive context, World Health Organization (WHO) categories were reported (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese).

- Physical activity (PA)

PA was assessed with the International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Short Form (IPAQ-SF) [30]. Following the standard scoring protocol, we calculated Total MET-minutes/week using 8.0 METs for vigorous, 4.0 METs for moderate, and 3.3 METs for walking, and derived IPAQ categories (Low/Moderate/High) using established thresholds. Because light-intensity activity was of specific interest, we also analyzed daily walking time (minutes/day) derived from the walking items of IPAQ.

- Mental-health outcomes

Symptoms of depression and anxiety were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); subscales for depression and anxiety (HADS-D and HADS-A) range 0–21 (higher = worse) [31]. Outcomes were analyzed continuously.

- Sleep

Sleep quality was measured with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); the global score (0–21; higher = worse) was used in analyses, with PSQI > 5 indicating poor sleep for descriptive reporting [32].

- Psycho-social covariates and screen time

Self-esteem was assessed with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [33] (higher = better). Daily social-media time and daily gaming time were self-reported (hours/day). Age (years) and sex (female vs. male) were included as demographic covariates.

2.3. Data Preparation

Analyses followed a prespecified plan prior to modeling. Data were inspected for range and logic inconsistencies. Pairwise deletion was used for bivariate statistics and listwise deletion for multivariable models and mediation. Primary models used raw BMI; for descriptive purposes we flagged implausible BMI values (≤12 or >40 kg/m2) and excluded them only from Table 1 (BMI n = 274). Primary multivariable models retained n = 277; in sensitivity analyses excluding BMI < 16 or >40 kg/m2, conclusions were unchanged.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the analytic sample (n = 277).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All tests were two-sided with α = 0.05. Analyses were conducted in Python 3.11. Normality was examined by Shapiro–Wilk (primary) and D’Agostino’s K2 (n ≥ 20). No raw continuous variable met normality at α = 0.05; hence, bivariate analyses used non-parametric tests (Spearman’s ρ; Mann–Whitney U/Kruskal–Wallis with Dunn–Holm), and multivariable inference relied on OLS residual diagnostics with conventional standard errors; conclusions were unchanged in sensitivity analyses using HC3 robust standard errors.

Descriptive statistics: Means, standard deviations, and distributional summaries were computed for continuous variables; counts and percentages for categorical variables.

Bivariate associations. We estimated Spearman correlations (ρ) between BMI, Total MET-minutes/week, daily walking time, and HADS-D/HADS-A. For IPAQ categories (Low/Moderate/High), we compared HADS scores using Kruskal–Wallis tests.

Multivariable models: We fit ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions for HADS-D and HADS-A, including BMI, BMI2, Total MET-minutes/week, sex, age, PSQI, social-media time, gaming time, and RSES as covariates. We report unstandardized coefficients, standard errors, p-values, 95% CIs, and model fit (R2). For visualization (forest plots), predictors were standardized (z-scores) and standardized betas were displayed with 95% CIs.

Walking-specific analyses: We examined walking indicators (e.g., minutes/day, walking METs, total walking minutes) against HADS-D/HADS-A via Spearman ρ and summarized results in a dedicated table.

Sex-stratified analyses: To explore potential effect heterogeneity, we computed sex-stratified correlations (female vs. male) for BMI, Total MET-minutes/week, and daily walking time with HADS-D/HADS-A and presented them as a table and forest-style figure.

Mediation analysis: We tested a parallel mediation model with walking time as predictor (X), PSQI global score and social-media time as mediators (M1, M2), and HADS-D or HADS-A as outcomes (Y), adjusting for age, sex, and BMI. All variables (except sex) were standardized prior to modeling. The a-paths (X→M1/M2) and b/c′ paths (M1/M2 and X→Y) were estimated via OLS. Indirect effects (X→M1→Y; X→M2→Y) and total indirect were quantified using non-parametric bootstrap (≥1200 resamples) with percentile 95% CIs. An indirect effect was considered significant when the 95% CI excluded 0. We summarize a, b, c, c′ coefficients and indirect effects in the mediation table and depict the model schematically.

Multiple comparisons and robustness: We emphasize effect sizes and compatibility intervals rather than multiplicity-adjusted p-values, consistent with our a priori focus on a limited set of theoretically motivated relationships (PA/Walking ↔ HADS; mediation via PSQI vs. social media). Robustness was examined via sensitivity exclusions for BMI extremes and by comparing crude vs. adjusted estimates.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

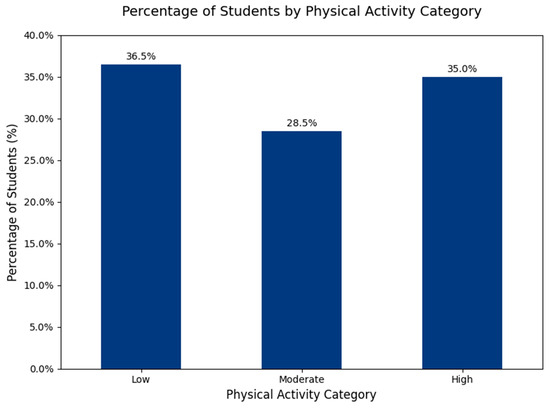

A total of 277 medical students were analysed. The mean age was 23.61 years (standard deviation (SD) = 8.23). Regarding ponderal status, 11.19% were underweight, 66.79% normal weight, 17.33% overweight, and 4.69% obese. According to the IPAQ classification, 36.50% of participants were categorized as having low physical activity, 28.50% moderate, and 35.00% high (Figure 1). Two-thirds of the sample reported poor sleep quality (PSQI > 5, 67.15%). Descriptive statistics for the main continuous variables are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Students Distribution by IPAQ Categories.

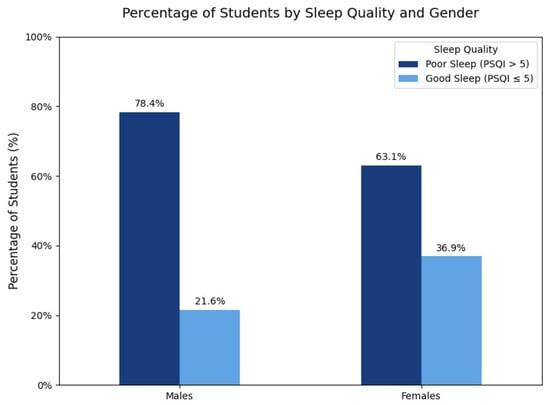

3.2. Sleep and Physical Activity Descriptives

Mean PSQI was 7.20 ± 3.43 (median 7 [5–9]); 67.15% (186/277) met the threshold for poor sleep (PSQI > 5). By sex, poor sleep prevalence was 78.38% in males vs. 63.05% in females (Figure 2) (χ2 p = 0.0239), whereas mean PSQI did not differ statistically (7.57 ± 2.83 vs. 7.06 ± 3.62, p = 0.114).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Poor Sleep Quality Among Students by Sex.

Total physical activity (IPAQ-SF) showed marked skew: median 2079 MET-min/week; interquartile range (IQR) 132–4551 mean 3309 ± 4260. Overall, 68.6% (190/277) met WHO’s minimum (≥600 MET-min/week), with no sex difference on prevalence (60.80% males vs. 71.43% females; p = 0.124). Daily walking time averaged 80.2 ± 68.3 min/day (median 80 [0–135]), with no statistically significant difference between females (83.7 ± 65.9) and males (70.4 ± 74.1; p = 0.1151). IPAQ categories were Low 36.5% (n = 101), Moderate 28.5% (n = 79), and High 35.0% (n = 97).

Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 summarize PSQI and IPAQ distributions overall and by sex (with Mann–Whitney U/χ2 tests), and the prevalence meeting WHO’s minimum (≥600 MET-min/week).

Table 2.

Sleep and Physical Activity Descriptives (Overall).

Table 3.

IPAQ category distribution (Overall).

Table 4.

Sleep and physical activity by sex with between-sex p-values.

3.3. Bivariate Associations

Spearman correlations were conducted to examine associations between BMI, physical activity, and depressive/anxiety symptoms (Table 5).

Table 5.

Spearman correlations between BMI, physical activity, and mental health outcomes.

- Physical activity and depression: Total MET-min/week correlated negatively and significantly with HADS-D (ρ = −0.19, p = 0.0015), indicating that more active students reported fewer depressive symptoms.

- Physical activity and anxiety: The association with HADS-A was non-significant (ρ = 0.00, p = 0.9835).

- BMI and symptoms: BMI showed no significant correlation with HADS-D (ρ = 0.09, p = 0.1486) or HADS-A (ρ = −0.07, p = 0.2560).

3.4. Group Comparisons by IPAQ Categories

We compared mean symptom scores across IPAQ levels (Low, Moderate, High) using Kruskal–Wallis tests (Table 6).

Table 6.

Mean HADS scores by IPAQ category (Low, Moderate, High).

- HADS-D: significant differences were found (p = 0.024). Students with low physical activity reported higher depressive symptoms compared to those with moderate or high activity.

- HADS-A: no significant group differences were observed (p = 0.92).

3.5. Multivariable Regression Models

We estimated OLS regression models for HADS-D and HADS-A including BMI, BMI2, Total MET, sex, age, PSQI TOTAL, time spent on social media, time gaming, and RSES (Table 7 and Table 8).

Table 7.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for depressive symptoms (HADS-D).

Table 8.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression for anxiety symptoms (HADS-A).

- Depressive Symptoms (HADS-D): The full model explained 23.61% of the variance in HADS-D scores (R2 = 0.236, F(9, 267) = 9.168, p < 0.001). Significant predictors included poor sleep quality (PSQI_TOTAL; β = 0.368, p < 0.001) and being female (β = −1.621, p = 0.001), which had a negative effect on depressive symptoms. Time spent on social media was also a significant negative predictor (β = −0.377, p = 0.014). Physical activity (Total MET) retained a borderline inverse effect (β = −0.0001, p = 0.072). Neither BMI nor BMI2 showed a significant effect.

- Anxiety Symptoms (HADS-A): The full model explained 21.2% of the variance in HADS-A scores (R2 = 0.212, F(9, 267) = 7.979, p < 0.001). Significant predictors were poor sleep quality (PSQI_TOTAL; β = 0.397, p < 0.001), which was positively associated with anxiety, and self-esteem (RSES; β = −0.126, p = 0.001), which was inversely associated. Neither total physical activity nor BMI showed a significant independent effect.

3.6. Walking Time Analyses

To further disentangle the role of light physical activity, we examined specific IPAQ walking-related variables in relation to depressive and anxiety symptoms (Table 9).

Table 9.

Spearman correlations between walking indicators and HADS outcomes.

- Associations with Depressive Symptoms (HADS-D): All three walking variables showed a significant negative correlation with depressive symptoms. The strongest association was with the number of days walked per week (ρ = −0.19, p = 0.002), indicating that a higher frequency of walking was related to fewer depressive symptoms. Similarly, daily walking time (ρ = −0.15, p = 0.012) and total walking METs (ρ = −0.15, p = 0.010) were also negatively correlated with HADS-D scores.

- Associations with Anxiety Symptoms (HADS-A): In contrast, walking variables showed no statistically significant association with anxiety symptoms. The correlations were weak for days walked per week (ρ = −0.11, p = 0.067), daily walking time (ρ = −0.03, p = 0.634), and total walking METs (ρ = −0.04, p = 0.526).

The findings suggest that walking, in terms of its frequency, duration, and energy expenditure, serves as a protective factor against depressive symptoms in this sample, but does not have a similar protective effect against anxiety.

3.7. Gender-Stratified Analyses

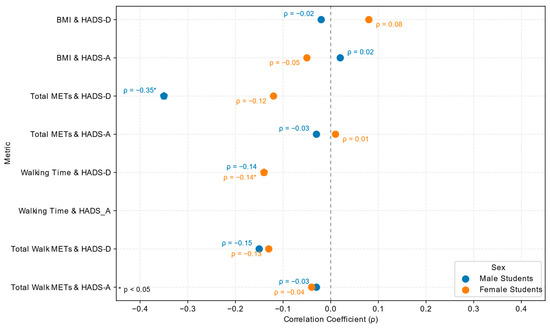

To explore potential sex differences, correlations between BMI, total physical activity, and walking time with depressive and anxiety symptoms were analyzed separately for males and females (Table 10, Figure 3).

Table 10.

Correlations Between Physical Activity, BMI, and Symptoms by Sex.

Figure 3.

Sex-stratified Spearman correlations (ρ) between physical activity, BMI, and mental-health outcomes (HADS-D and HADS-A). Blue = male students; orange = female students. Star-shaped symbols (★) denote statistically significant correlations (p < 0.05). Negative ρ values indicate inverse relationships (higher activity or walking time associated with lower depressive symptom scores).

The correlations between physical activity, BMI, and mental health symptoms show sex-specific patterns.

- Female Students: Among female students, walking time showed a significant negative correlation with depressive symptoms (ρ = −0.14, p = 0.0443), but no significant association with anxiety symptoms (ρ = −0.02, p = 0.7294). In contrast, total METs were not significantly associated with depression (ρ = −0.12, p = 0.0759) or anxiety (ρ = 0.01, p = 0.8675).

- Male Students: Among male students, the strongest association was observed for total METs and depressive symptoms, with a significant negative correlation (ρ = −0.35, p = 0.0021). Walking time did not significantly correlate with either depression (ρ = −0.14, p = 0.2239) or anxiety (ρ = −0.05, p = 0.6796).

These findings suggest a sex-specific pattern: female students appear to benefit more psychologically from light-intensity activity such as walking, while male students may derive greater psychological benefit from vigorous or overall higher-intensity physical activity.

3.8. Mediation Analyses

We estimated OLS regression models for HADS-D and HADS-A to explore parallel mediation pathways through sleep quality and social media time, adjusted for age, sex, and BMI.

For depressive symptoms, there was no significant total effect of walking time on HADS-D (β = −0.0052, p = 0.1082). Consistent with this, neither the direct path (β = −0.0029, p = 0.3405) nor the indirect paths via sleep quality (95% CI [−0.0037, 0.0015]) or social media use (95% CI [−0.0028, 0.0000]) were found to be significant. The results did not provide evidence for mediation as the effect of walking on depressive symptoms was non-significant throughout the model.

Similarly, for anxiety symptoms, there was no significant total effect of walking time on HADS-A (β = −0.0005, p = 0.9046). Both the direct path and the indirect paths through sleep quality and social media time were also non-significant.

3.9. Concise Summary of Results

Among 277 medical students, poor sleep was common (67.1%). In bivariate analyses, higher total physical activity related to fewer depressive symptoms (ρ = −0.19, p = 0.0015), whereas walking indicators were inversely associated with depression but not anxiety; BMI showed no associations. In multivariable models (R2 = 0.236 for HADS-D; R2 = 0.212 for HADS-A), sleep quality was the strongest independent correlate of both depression (β = 0.37, p < 0.001) and anxiety (β = 0.40, p < 0.001); total physical activity showed only a borderline inverse association with depression and was null for anxiety; BMI had no independent effect. Sex-stratified correlations suggested that females benefit more from walking, whereas in males higher total activity relates to fewer depressive symptoms. Parallel-mediation analyses via sleep and social-media time were null.

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

This cross-sectional study investigated the relationship between physical activity, BMI, and depressive and anxiety symptoms in Romanian medical students. This research also examined the potential roles of sleep quality and screen time as contributing factors. The study aimed to clarify which modifiable behaviors are most influential for this specific population to inform targeted prevention strategies.

The finding of a negative correlation between overall physical activity and depressive symptoms among students is strongly supported by current evidence. Multiple large-scale studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that higher levels of physical activity are associated with lower depressive symptom scores in university and high school populations, with the relationship being dose-dependent—students with low physical activity consistently report higher depressive symptoms compared to those with moderate or high activity levels [9,35,36,37,38,39,40]. While our bivariate findings align with literature suggesting PA is a protective factor, this effect was not supported in our more comprehensive multivariable model. This suggests that the relationship between total PA volume and depression may be mediated or confounded by other variables, such as sleep quality, in this specific cohort. The literature also indicates that physical activity exerts its protective effect on depression through mediating factors such as self-esteem, positive psychological capital, and social support, which further reduce depressive symptoms [35,37]. Specific depressive symptoms most affected by physical activity include anhedonia and fatigue, with a monotonic dose–response relationship observed for these domains [41].

Regarding anxiety symptoms, the evidence is less consistent. While some studies report that physically inactive students have higher anxiety scores, the association between physical activity and anxiety is generally weaker and often not statistically significant after adjustment for confounders [38,42].

There is robust evidence that walking, even at light intensity and modest frequency, is associated with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms. Large-scale meta-analyses and cohort studies consistently demonstrate an inverse, curvilinear dose–response relationship: the greatest mental health benefits are observed when individuals move from no activity to some activity, with diminishing returns at higher levels of physical activity [9,12,43]. For example, accumulating a volume of physical activity equivalent to 2.5 h of brisk walking per week is associated with a 25% lower risk of depression, and even half that dose confers an 18% lower risk compared to inactivity [9].

Daily step count data further support these findings: adults who achieve 5000 or more steps per day report fewer depressive symptoms, and those exceeding 7500 steps per day have a 42% lower prevalence of depression compared to those with fewer than 5000 steps [12]. Importantly, these protective effects are evident with walking and do not require vigorous exercise, making walking a highly accessible and low-cost intervention.

Among college students, higher frequency and duration of walking are specifically correlated with lower depressive symptom scores and engaging in physical activity more than three times per week for 30–59 min is associated with a significantly lower detection rate of cognitive symptoms and suicidal ideation [36,39,44]. The relationship is partially mediated by improvements in sleep quality and behavioral activation, but the direct effect of physical activity remains substantial [36,44].

In summary, even light-intensity physical activity such as walking is a protective factor against depression, and increasing walking days per week and minutes per day can be recommended as a practical, evidence-based strategy for reducing depressive symptoms in students and adults.

Current evidence supports sex-specific recommendations for physical activity to support mental health in students. Multiple large-scale studies demonstrate that for female students, walking time and lower-intensity activities are more consistently associated with fewer depressive symptoms, while for male students, higher-intensity physical activity (such as moderate-to-vigorous exercise or activities with higher total metabolic equivalents) shows a stronger inverse relationship with depressive symptoms [45,46,47,48,49,50].

For females, walking more than once per week is associated with lower depression levels, and reallocating sedentary time to walking or moderate-intensity activity is beneficial [45,46]. In contrast, for males, engaging in strength or vigorous exercise more than once per week, or increasing overall moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, is linked to reduced depressive symptoms [45,46,48,49]. These patterns are consistent across diverse populations and are robust to adjustment for confounders.

The literature also highlights that the context and type of physical activity matter: leisure-time physical activity is more protective for mood than occupational or household activity, and the benefits of physical activity for mental health are greater when tailored to sex-specific preferences and physiological responses [50].

In summary, recommendations for physical activity to support mental health should be tailored by sex: emphasizing walking and moderate activity for females, and higher-intensity or strength-based activity for males, to optimize reductions in depressive symptoms among student populations.

Poor sleep quality is a strong, independent predictor of both depressive and anxiety symptoms among medical students, as consistently demonstrated in recent cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Multiple analyses using validated instruments (e.g., Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7)) show that poor sleep quality is directly associated with increased risk and severity of depression and anxiety, even after controlling for confounders such as sex, academic year, and psychosocial stressors [51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61].

Longitudinal data further support a bidirectional relationship: poor sleep quality predicts future onset and worsening of depressive and anxiety symptoms, and conversely, baseline depression and anxiety can worsen sleep quality over time [54,62]. Mediation analyses indicate that sleep quality often serves as a key mechanism linking stress, negative life events, and psychological distress to mental health outcomes in this population [52,53,57,59,60,61].

The clinical implication is that interventions targeting sleep quality—such as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, sleep hygiene education, and resilience-building—may be effective strategies to mitigate depressive and anxiety symptoms in medical students. These findings reinforce the robust connection between sleep and mental health, underscoring the importance of routine screening and integrated management of sleep disturbances in this high-risk group.

Current evidence indicates that the association between body mass index (BMI) and depressive or anxiety symptoms is complex and context-dependent. Large population-based studies consistently report a U-shaped relationship, with both underweight and obesity associated with increased risk of depression, while normal BMI is associated with lower risk [63,64,65,66]. However, when confounding factors such as lifestyle, academic stress, and internet use are accounted for—particularly in narrow cohorts like medical students—the direct association between BMI and depressive or anxiety symptoms may attenuate or become non-significant [22,67]. It is important to acknowledge that the narrow distribution of BMI in our specific student population (median 22.41 kg/m2) may have reduced the power to detect subtle or curvilinear associations, which is a common limitation in similar homogenous samples.

In medical students, academic burnout and internet addiction have been shown to mediate the relationship between overweight/obesity and mental health symptoms, suggesting that lifestyle and psychosocial factors may be more influential than BMI alone in this population [22]. This finding challenges the generalizability of population-based associations to specific subgroups, where unique stressors and coping mechanisms may play a larger role.

Regarding screen time, while it is a significant predictor of depressive symptoms in some studies, its explanatory value is modest and inconsistent across different populations and study designs [65]. Screen time may interact with other factors such as social comparison, body image concerns, and academic stress, but it does not fully account for the variance in depressive symptoms.

In summary, the link between BMI and mental health is less clear in narrowly defined cohorts like medical students when lifestyle factors are considered, and screen time, although relevant, is a modest and inconsistent predictor of depressive symptoms.

While physical activity, including walking, is robustly associated with reduced depressive symptoms, mediation analyses have shown mixed results regarding the roles of sleep and social media use.

For sleep, some studies have found partial mediation, indicating that improvements in sleep quality can explain part of the mental health benefits of physical activity, but not all. For example, Kaseva et al. found that sleep problems mediated approximately 30–36% of the association between physical activity and depressive symptoms, but this effect was attenuated after adjusting for baseline depression, suggesting that other pathways are also important [68]. Similarly, Barham et al. reported that sleep health mediated only 19% of the association between physical activity and depression symptoms, indicating that the majority of the effect is direct or mediated by other factors [69].

Regarding social media use, Wang et al. demonstrated that physical activity is associated with lower depression and anxiety, and that high social media use is associated with worse mental health outcomes but did not establish social media use as a mediator between physical activity and mental health [70]. Systematic reviews further support that while social media use and sleep quality are independently associated with mental health, their roles as mediators in the physical activity–mental health relationship are limited or inconsistent [71,72].

Therefore, the finding that the beneficial effect of walking on mental health is not accounted for by improvements in sleep or alterations in social media use is supported by current evidence, which suggests that walking likely exerts its mental health benefits through direct physiological and psychological mechanisms, rather than primarily through changes in sleep or social media behaviors.

4.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The association between physical activity and mental health is indeed not a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. Recent evidence demonstrates that both the type and intensity of physical activity, as well as sex, can moderate mental health benefits. For example, large-scale cross-sectional and meta-analytic studies show that leisure-time physical activity—especially activities such as walking, running, cycling, and team sports—are more strongly associated with reduced odds of depression and improved mental health than aggregate measures like total metabolic equivalents (METs) alone [73,74,75].

Importantly, sex-specific differences have been identified: vigorous-intensity activity is more strongly associated with reduced depression and anxiety in men, while walking and moderate-intensity activity confer greater emotional well-being benefits in women [76]. These findings challenge the traditional approach of using aggregate weekly METs as the sole metric and support the use of activity-specific and domain-specific measures in both research and clinical recommendations [74,76].

Furthermore, the dose–response relationship is curvilinear, with the greatest mental health benefits observed when moving from inactivity to low or moderate levels of activity, and diminishing returns at higher doses [9,77]. The qualitative aspects of activity—such as social interaction, outdoor environment, and personal preference—also mediate these effects [73,74,78].

In summary, future research and clinical practice should prioritize nuanced, activity-specific, and sex-sensitive physical activity metrics rather than relying solely on aggregate METs, to optimize mental health outcomes.

The lack of a significant association between body mass index (BMI) and depressive or anxiety symptoms in medical student cohorts is consistent with emerging evidence that the well-established U-shaped relationship between BMI and mental health in the general population may not generalize to more homogenous, young adult populations such as medical students. Large population-based studies consistently demonstrate a U-shaped or dose-dependent association between BMI and depression, with both underweight and obesity conferring increased risk for depressive symptoms, and sometimes anxiety, across diverse adult and adolescent samples [63,64,65,66,79,80,81]. However, these associations are often attenuated or absent in younger, healthier, and more socioeconomically homogenous cohorts.

Recent studies specifically in medical students suggest that while overweight and obesity may be associated with increased depressive and anxiety symptoms, these relationships are frequently mediated by behavioral and psychosocial factors such as academic burnout and internet addiction, rather than BMI alone [22]. In young adult twin cohorts, elevated BMI is associated with poorer physical well-being and, to a lesser extent, depressive symptoms, but not with anxiety or social well-being, further supporting the notion that BMI-mental health associations are context-dependent and may be less pronounced in healthy, educated young adult [67,82].

These findings support the importance of prioritizing behavioral and psychosocial risk factors—such as academic stress, burnout, and maladaptive coping behaviors—over BMI alone when assessing mental health risk in medical students and similar cohorts. This approach aligns with the evolving understanding that mental health in young adults is multifactorial and less directly tied to BMI than in the general population.

The medical literature consistently demonstrates a strong and independent association between poor sleep quality and increased depressive and anxiety symptoms, particularly in high-stress populations such as those exposed to chronic stressors or pandemic conditions [54,62,83,84,85,86]. Sleep quality is repeatedly shown to be a central determinant of mental health, with bidirectional relationships observed: poor sleep predicts future depression and anxiety, and these symptoms also worsen sleep quality over time [54,62].

Importantly, several studies indicate that sleep quality functions as a distinct and independent pathway to mental health, rather than merely mediating the effects of physical activity on depression and anxiety. For example, while physical activity is associated with improved sleep and reduced depressive symptoms, mediation analyses reveal that sleep only partially mediates this relationship, and in some cases, the mediation effect disappears after adjusting for baseline depressive symptoms [68,69]. Other studies show that the negative impact of poor sleep quality on depressive symptoms is amplified in physically inactive individuals, but sleep and physical activity exert independent effects [6]. Furthermore, emotion regulation and adaptive coping strategies are independently associated with mental health outcomes, and their benefits are contingent on sleep quality, further supporting the notion that sleep is a unique pathway [84,87].

In summary, sleep quality is a central and independent determinant of mental well-being in high-stress populations, and its effects on depression and anxiety are not fully explained by its relationship with physical activity. This underscores the importance of directly targeting sleep quality in interventions aimed at improving mental health.

The most significant practical implication of our findings is the need for sex-specific recommendations for physical activity in mental health interventions for medical students. The study showed that for female students, walking time was a significant protective factor against depressive symptoms, while for male students, higher overall physical activity (Total METs) was more strongly associated with fewer depressive symptoms. This suggests that “one-size-fits-all” advice on physical activity may be less effective. By tailoring interventions, such as promoting accessible, light-intensity activities like walking for female students and encouraging vigorous exercise for male students, medical programs could achieve higher engagement and better mental health outcomes. This approach moves beyond generic guidance and offers a more personalized, evidence-based strategy to address the unique needs of different student groups.

A significant practical implication of this study is the clear roadmap it provides for universities and medical schools to develop evidence-based interventions that focus on modifiable lifestyle factors. Our findings, which found no significant association between BMI and depressive or anxiety symptoms, align with current evidence that suggests poor sleep quality and insufficient physical activity are highly prevalent and strongly associated with adverse health outcomes in university students, independent of BMI alone [88,89,90,91]. Therefore, prevention programs should prioritize improving sleep quality and increasing physical activity levels, as these are actionable and have demonstrated benefits for both physical and mental health in university settings. This approach is consistent with recommendations from leading professional societies, such as the American Heart Association, which highlights the effectiveness of behavioral interventions focused on physical activity and sleep health for promoting well-being and risk reduction [92]. Interventions targeting sleep hygiene and regular physical activity are recommended as first-line strategies, as students with better sleep quality and higher levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) show improved physical fitness and lower stress perception, regardless of BMI status.

Another important practical implication is that walking can be promoted as a simple, low-cost intervention. The finding that walking is a protective factor against depressive symptoms is consistent with a recent meta-analysis showing that even modest increases in daily step counts are associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms [12]. This reinforces the idea that “something is better than nothing”. Medical schools can leverage this by encouraging students to integrate short walks into their routines, perhaps through “walk-and-talk” study groups or by promoting the use of stairs over elevators. These interventions are supported by evidence that structured walking programs can reduce depression and improve well-being in student populations [93,94]. This makes beneficial behavior accessible to all students, regardless of their fitness level or access to exercise facilities and aligns with World Health Organization recommendations for regular activity to improve health and reduce the risk of depression [95].

Romanian medical education involves dense curricula and frequent high-stakes assessments, which may heighten psychological distress and shape coping behaviours. In this setting, a visible gym-oriented trend among some male students (bodybuilding/strength training) is time-intensive and may be difficult to reconcile with academic demands, whereas female students more often adopt lower-barrier activities such as walking. Campus features, a dispersed, multi-site teaching layout with constrained parking capacity—encourage active commuting between buildings, consistent with the comparatively high baseline walking observed. These contextual features help interpret the sex-specific patterns in our data while avoiding overgeneralization.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

This investigation possesses several significant methodological and conceptual strengths. A key strength is its contribution to the underrepresented body of literature on the mental health of Romanian medical students, offering a unique regional perspective that expands upon findings from Western cohorts. The use of validated and widely accepted psychometric instruments, such as the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), ensures the reliability and comparability of our measurements across studies. Furthermore, our comprehensive modeling strategy, which integrated a broad spectrum of demographic, behavioral, and psychological variables, allowed for a more detailed understanding of their complex interrelationships. The formal sex-stratified analysis is a particularly robust feature of our design, as it uncovered distinct sex-specific associations between physical activity types and mental health outcomes, thereby challenging the utility of a uniform, aggregate approach to physical activity promotion.

Despite these strengths, the study is subject to several important limitations. The cross-sectional design fundamentally precludes any causal inferences; while we observed significant associations, the directionality of these relationships—for example, whether a lack of physical activity contributes to depression or vice versa—cannot be determined. The data, being self-reported, introduces the potential for recall and social desirability biases, which could compromise the accuracy of measurements for physical activity, sleep quality, and screen time. Additionally, our analytic sample size, while adequate for primary analyses, may have been underpowered to detect subtle or curvilinear effects, such as the BMI-mental health relationship, particularly within a population that exhibits a narrow BMI range. Finally, the study’s focus on a specific regional cohort limits the generalizability of our findings to medical students in other cultural or academic contexts, highlighting the need for replication in diverse populations.

5. Conclusions

This cross-sectional study of Romanian medical students underscores the significant impact of specific lifestyle behaviors on mental health, with distinct patterns emerging for depressive and anxiety symptoms. Our findings confirm that physical activity, particularly walking, is a protective factor against depressive symptoms. This relationship is not uniform, as the psychological benefits appear to be sex-specific: female students showed a significant link between walking and reduced depressive symptoms, while male students benefited more from overall higher-intensity physical activity.

The study also reinforces the critical importance of sleep quality, which emerged as a strong and independent predictor for both depressive and anxiety symptoms. In contrast, we found no significant association between body mass index (BMI) and mental health outcomes when controlling other factors, suggesting that focusing on modifiable behaviors like sleep and physical activity may be more relevant for this specific population. The lack of a significant mediating effect through sleep or social media use indicates that these factors are not the primary mechanisms linking walking to mental health in this cohort. The protective effects of physical activity are thus likely direct or mediated by other unmodelled physiological or psychosocial factors, such as self-efficacy or neurotrophic processes.

In summary, these findings provide a clear, evidence-based roadmap for developing targeted, sex-specific interventions within medical education. By promoting both improved sleep hygiene and tailored physical activity—emphasizing walking for female students and higher-intensity activities for male students—universities can implement effective and accessible strategies to mitigate the high burden of depressive and anxiety symptoms in their medical student population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.-C. and A.P.-C.; methodology, C.P.-C.; software, C.P.-C. and S.I.N.; validation, C.P.-C., A.P.-C. and L.-A.M.; formal analysis, V.-I.S.; investigation, L.B.; resources, S.I.N.; data curation, C.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.-C.; writing—review and editing, A.P.-C., and V.-I.S.; visualization, L.-A.M.; supervision, C.P.-C., and L.B.; project administration, C.P.-C., and L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Galaţi College of Physicians, no. 1165/29 November 2024, approval date 29 November 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated during the current study is available in the Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17073937 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT, version 4.0 (OpenAI) for assistance with English translation, grammatical corrections, and to improve the fluency of expression. After using the AI tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content and took full responsibility for the final version of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | body mass index |

| CI | confidence interval |

| GAD-7 | Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HADS-A | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Anxiety subscale |

| HADS-D | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Depression subscale |

| HC3 | Heteroscedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator 3 |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| IPAQ-SF | International Physical Activity Questionnaire—Short Form |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| MET | metabolic equivalent of task |

| MVPA | moderate-to-vigorous physical activity |

| OLS | ordinary least squares |

| PA | physical activity |

| PHQ | Patient Health Questionnaire |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| RSES | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Bert, F.; Lo Moro, G.; Corradi, A.; Acampora, A.; Agodi, A.; Brunelli, L.; Chironna, M.; Cocchio, S.; Cofini, V.; D’Errico, M.M.; et al. Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms among Italian Medical Students: The Multicentre Cross-Sectional “PRIMES” Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahrami, H.; AlKaabi, J.; Trabelsi, K.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Saif, Z.; Seeman, M.V.; Vitiello, M.V. The Worldwide Prevalence of Self-Reported Psychological and Behavioral Symptoms in Medical Students: An Umbrella Review and Meta-Analysis of Meta-Analyses. J. Psychosom. Res. 2023, 173, 111479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; et al. The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Mental Problems in Medical Students during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 321, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duica, C.L.; Negoita, S.I.; Pleșea-Condratovici, A.; Moroianu, L.-A.; Ignat, M.D.; Nicolcescu, P.; Ciubara, A.; Robles-Rivera, K.; Mititelu-Tartau, L.; Pleșea-Condratovici, C. Depression in Romanian Medical Students—A Study, Systematic Review, and Meta-Analysis. JCM 2025, 14, 5853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaseri, K.; Atsariyasing, W.; Pornnoppadol, C.; Sanguanpanich, N.; Srifuengfung, M. Mental Problems and Risk Factors for Depression among Medical Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicine 2022, 101, e30629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, K.M.; Ahmadi, H.; Uban, K.A.; Riis, J.L. Behavioral and Psychosocial Factors Related to Mental Distress among Medical Students. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1225254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidović, S.; Rakić, N.; Kraštek, S.; Pešikan, A.; Degmečić, D.; Zibar, L.; Labak, I.; Heffer, M.; Pogorelić, Z. Sleep Quality and Mental Health Among Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.; Garcia, L.; Abbas, A.; Strain, T.; Schuch, F.B.; Golubic, R.; Kelly, P.; Khan, S.; Utukuri, M.; Laird, Y.; et al. Association Between Physical Activity and Risk of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions for Improving Depression, Anxiety and Distress: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noetel, M.; Sanders, T.; Gallardo-Gómez, D.; Taylor, P.; del Pozo Cruz, B.; van den Hoek, D.; Smith, J.J.; Mahoney, J.; Spathis, J.; Moresi, M.; et al. Effect of Exercise for Depression: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2024, 384, e075847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzozero-Peroni, B.; Díaz-Goñi, V.; Jiménez-López, E.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, E.; Sequí-Domínguez, I.; Núñez De Arenas-Arroyo, S.; López-Gil, J.F.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Mesas, A.E. Daily Step Count and Depression in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2451208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Ding, H.; Zhang, D.; Cheung, P.M.-H.; Yang, Z.; Tam, K.W.; Zhou, W.; Chan, D.C.-C.; Wang, W.; et al. The Effect of Walking on Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e48355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, C.E.; Hillman, C.H.; Bloodgood Sheppard, B.; Tennant, B.; Conroy, D.E.; Macko, R.F.; Marquez, D.X.; Petruzzello, S.J.; Powell, K.E.; Erickson, K.I. Physical Activity and Sleep: An Updated Umbrella Review of the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 58, 101489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredlow, M.A.; Capozzoli, M.C.; Hearon, B.A.; Calkins, A.W.; Otto, M.W. The Effects of Physical Activity on Sleep: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binjabr, M.A.; Alalawi, I.S.; Alzahrani, R.A.; Albalawi, O.S.; Hamzah, R.H.; Ibrahim, Y.S.; Buali, F.; Husni, M.; BaHammam, A.S.; Vitiello, M.V.; et al. The Worldwide Prevalence of Sleep Problems Among Medical Students by Problem, Country, and COVID-19 Status: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression of 109 Studies Involving 59427 Participants. Curr. Sleep Med. Rep. 2023, 9, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlKhenaizi, A.K.; Shakeeb, F.N.; Fredericks, S.; Gaynor, D. Physical Activity Levels, Recreational Screen Time, Sleep Quality and Mood among Young Adult Healthcare Students at an International University in Bahrain: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e093655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, B.; Daines, B.; Allen, M.; Pulsipher, K.; Zapata, I.; Wilde, B. Mental Health and Sleep Habits during Preclinical Years of Medical School. Sleep Med. 2022, 100, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabane, S.; Chaabna, K.; Khawaja, S.; Aboughanem, J.; Mittal, D.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. Sleep Disorders and Associated Factors among Medical Students in the Middle East and North Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, K.; Zheng, J.; Kong, L.; Gu, J.; Huang, T. Association of Screen Time with Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in College Students During COVID-19 Outbreak in Shanghai: Mediation Role of Sleep Quality. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2023, 26, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, L.; Bergmann, A.; Voigt, K.; Balogh, E.; Birkas, B.; Faubl, N.; Kraft, T.; Schöniger, K.; Riemenschneider, H. Screen Time and Sleep among Medical Students in Germany. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Zhao, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, C.; Zhai, J.; Wang, B. Depression, Anxiety, Stress Symptoms among Overweight and Obesity in Medical Students, with Mediating Effects of Academic Burnout and Internet Addiction. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoseini, M.; Bardoon, S.; Bakhtiari, A.; Adib-Rad, H.; Omidvar, S. Structural Model of the Relationship between Physical Activity and Students’ Quality of Life: Mediating Role of Body Mass Index and Moderating Role of Gender. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, X.; Zou, L.; Hu, J.; Wang, Y.; Hao, M. The Effects of Body Dissatisfaction, Sleep Duration, and Exercise Habits on the Mental Health of University Students in Southern China during COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, S.; Zhang, X.; Taleb, Z.B.; Gu, X. The Associations of Physical Activity and Health-Risk Behaviors toward Depressive Symptoms among College Students: Gender and Obesity Disparities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoet, G. PsyToolkit: A Novel Web-Based Method for Running Online Questionnaires and Reaction-Time Experiments. Teach. Psychol. 2017, 44, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G. PsyToolkit: A Software Package for Programming Psychological Experiments Using Linux. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.; Marshall, A.; Sjostrom, M.; Bauman, A.; Lee, P.; Macfarlane, D.; Lam, T.; Stewart, S. International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form. J. Am. Coll. Health 2017, 65, 492–501. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A New Instrument for Psychiatric Practice and Research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Meas. Package 1965, 61, 18. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-001512-8. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/336656 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Wei, X.; Lai, Z.; Tan, Z.; Ou, Z.; Feng, X.; Xu, G.; Ai, D. The Effect of Physical Activity on Depression in University Students: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Positive Psychological Capital. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1485641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Qiu, S.; Xin, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, X. Correlation of Exercise Participation, Behavioral Inhibition and Activation Systems, and Depressive Symptoms in College Students. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hao, F. The Influence of Physical Activity on the Mental Health of High School Students: The Chain Mediating Effects of Social Support and Self-Esteem. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, E.E.S.D.; Neves, L.M.; Souza, K.C.D.; Mendes, T.B.; Rossi, F.E.; Silva, A.A.D.; Oliveira, R.D.; Perilhão, M.S.; Roschel, H.; Gil, S. Physically Inactive Undergraduate Students Exhibit More Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Poor Quality of Life than Physically Active Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, X. Latent Profile Analysis of Depressive Symptoms in College Students and Its Relationship with Physical Activity. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 351, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Skoog, J.; Wichstrøm, L. Symptoms of Depression, Physical Activity, and Sedentary Time: Within-Person Relations from Age 6 to 18 in a Birth Cohort. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2025, 64. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, E.; Rosenström, T.; Määttänen, I.; Jokela, M. Physical Activity and Specific Symptoms of Depression: A Pooled Analysis of Six Cohort Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 348, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Yu, F.; Guo, Z.; Jia, S.; Wang, X. Canonical Correlation Analysis of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms among College Students and Their Relationship with Physical Activity. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.P.; Dishman, R.K.; Hallgren, M.; MacDonncha, C.; Herring, M.P. Associations of Physical Activity and Depression: Results from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 112, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Xin, X.; Wang, G.; Chen, J.; Karina, S.; Tian, Y. Correlation between Physical Exercise Levels, Depressive Symptoms, and Sleep Quality in College Students: Evidence from Electroencephalography. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 369, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, M.C.; Romano, I.; Butler, A.; Laxer, R.E.; Patte, K.A.; Leatherdale, S.T. Bi-Directional Relationships between Physical Activity and Mental Health among a Large Sample of Canadian Youth: A Sex-Stratified Analysis of Students in the COMPASS Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 2021, 18, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jeong, W.; Kwon, J.; Kim, Y.; Jang, S.-I.; Park, E.-C. Sex Differences in Type of Exercise Associated with Depression in South Korean Adults. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, F.; Li, X.; Jia, L.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, D.; Wan, Y. Substitutions of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior with Negative Emotions and Sex Difference among College Students. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2024, 72, 102605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahuas, A.; He, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, W. Relationship of Physical Activity and Sleep with Depression in College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavin, E.E.; Matthew, J.; Spaeth, A.M. Gender Differences in the Relationship Between Exercise, Sleep, and Mood in Young Adults. Health Educ. Behav. 2022, 49, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurvydas, A.; Istomina, N.; Dadeliene, R.; Majauskiene, D.; Strazdaite, E.; Lisinskiene, A.; Valanciene, D.; Uspuriene, A.B.; Sarkauskiene, A. Mood Profile in Men and Women of All Ages Is Improved by Leisure-Time Physical Activity Rather than Work-Related Physical Activity. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, G.; Rajapakshe, D.P.R.W.; Wijayaratna, D.R.; Jayakody, J.A.I.P.; Gunaratne, K.A.M.C.; Alagiyawanna, A.M.A.D.K. Psychological Distress and Sleep Quality among Sri Lankan Medical Students during an Economic Crisis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tuersun, Y.; Yang, J.; Xiong, M.; Wang, Y.; Rao, X.; Jiang, S. Association of Depression Symptoms and Sleep Quality with State-Trait Anxiety in Medical University Students in Anhui Province, China: A Mediation Analysis. BMC Med. Educ 2022, 22, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, M.; Vestri, A. The Mediating Role of Sleep Quality in the Relationship between Negative Emotional States and Health-Related Quality of Life among Italian Medical Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, K.; Hou, G.; Yang, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, H.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, G.; et al. Poorer Sleep Quality Correlated with Mental Health Problems in College Students: A Longitudinal Observational Study among 686 Males. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 136, 110177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares-Garrido, M.J.; Morocho-Alburqueque, N.; Zila-Velasque, J.P.; Solis, L.A.Z.; Saldaña-Cumpa, H.M.; Rueda, D.A.; Chiguala, C.I.P.; Jiménez-Mozo, F.; Valdiviezo-Morales, C.G.; Alburqueque, E.S.B.; et al. Sleep Quality and Associated Factors in Latin American Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional and Multicenter Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yin, J.; Cai, X.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Y. Association between Sleep Duration and Quality and Depressive Symptoms among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wen, X.; Li, Y.; Luo, C. Association of Perceived Stress and Sleep Quality among Medical Students: The Mediating Role of Anxiety and Depression Symptoms during COVID-19. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1272486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudo, K.; Ehring, E.; Fuchs, S.; Herget, S.; Watzke, S.; Unverzagt, S.; Frese, T. The Association of Sleep Patterns and Depressive Symptoms in Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Res. Notes 2022, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Shi, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, M.; Hua, L.; Jin, Y.; Chang, W. Associations between Chinese College Students’ Anxiety and Depression: A Chain Mediation Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, Z.; Meng, Q. Negative Life Events, Sleep Quality and Depression in University Students. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Guo, J.; Zhou, J.; Lai, Y. Psychological Resilience Mediates the Association between Sleep Quality and Anxiety Symptoms: A Repeated Measures Study in College Students. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.V.; Zainal, N.H.; Newman, M.G. Why Sleep Is Key: Poor Sleep Quality Is a Mechanism for the Bidirectional Relationship between Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder Across 18 Years. J. Anxiety Disord. 2022, 90, 102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Pang, T.; Huang, H. The Relationship between Depressive Symptoms and BMI: 2005–2018 NHANES Data. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 313, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, C.; Ye, J.; Zhao, W. The Relationship between BMI and Depression: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1410782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, M.; Machado, D.B.; Jin, H.; Scherer, N.; Sun, W.; Sha, F.; Smythe, T.; Ford, T.J.; et al. Dose-Dependent Association Between Body Mass Index and Mental Health and Changes Over Time. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffroy, M.-C.; Li, L.; Power, C. Depressive Symptoms and Body Mass Index: Co-Morbidity and Direction of Association in a British Birth Cohort Followed over 50 Years. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 2641–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahle, B.W.; Breslin, M.; Sanderson, K.; Patton, G.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A.; Gall, S. Association between Depression, Anxiety and Weight Change in Young Adults. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaseva, K.; Dobewall, H.; Yang, X.; Pulkki-Råback, L.; Lipsanen, J.; Hintsa, T.; Hintsanen, M.; Puttonen, S.; Hirvensalo, M.; Elovainio, M.; et al. Physical Activity, Sleep, and Symptoms of Depression in Adults—Testing for Mediation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barham, W.T.; Buysse, D.J.; Kline, C.E.; Kubala, A.G.; Brindle, R.C. Sleep Health Mediates the Relationship between Physical Activity and Depression Symptoms. Sleep Breath 2022, 26, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, M. Association between Social Media Use, Physical Activity Level, and Depression and Anxiety among College Students: A Cross-Cultural Comparative Study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, R.; Hussain, J.; Stranges, S.; Anderson, K.K. Interplay between Social Media Use, Sleep Quality, and Mental Health in Youth: A Systematic Review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 56, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, O.; Walsh, E.I.; Dawel, A.; Alateeq, K.; Espinoza Oyarce, D.A.; Cherbuin, N. Social Media Use, Mental Health and Sleep: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analyses. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 367, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, T.S.; Lopes, M.V.V.; Da Costa, B.G.G.; Silva, K.S.; Schuch, F.B. Relationship between Types of Physical Activity and Depression among 88,522 Adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teychenne, M.; Sousa, G.M.; Baker, T.; Liddelow, C.; Babic, M.; Chauntry, A.J.; France-Ratcliffe, M.; Guagliano, J.; Christie, H.E.; Tremaine, E.M.; et al. Domain-Specific Physical Activity and Mental Health: An Updated Systematic Review and Multilevel Meta-Analysis in a Combined Sample of 3.3 Million People. Br. J. Sports Med. 2025, bjsports-2025-109806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Huang, Y.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ren, Z.; Ye, R.; Yao, Z.; Chen, J.; Lin, Z.; Gao, Y.; et al. Relationship between Physical Activity and Mental Health in a National Representative Cross-Section Study: Its Variations According to Obesity and Comorbidity. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 308, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asztalos, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Cardon, G. The Relationship between Physical Activity and Mental Health Varies across Activity Intensity Levels and Dimensions of Mental Health among Women and Men. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, P.; Doré, I.; Romain, A.-J.; Hains-Monfette, G.; Kingsbury, C.; Sabiston, C. Dose Response Association of Objective Physical Activity with Mental Health in a Representative National Sample of Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Vella, S.; Biddle, S.; Sutcliffe, J.; Guagliano, J.M.; Uddin, R.; Burgin, A.; Apostolopoulos, M.; Nguyen, T.; Young, C.; et al. Physical Activity and Mental Health: A Systematic Review and Best-Evidence Synthesis of Mediation and Moderation Studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act 2024, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herhaus, B.; Kersting, A.; Brähler, E.; Petrowski, K. Depression, Anxiety and Health Status across Different BMI Classes: A Representative Study in Germany. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wit, L.; Have, M.T.; Cuijpers, P.; De Graaf, R. Body Mass Index and Risk for Onset of Mood and Anxiety Disorders in the General Population: Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2 (NEMESIS-2). BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, L.M.; Van Straten, A.; Van Herten, M.; Penninx, B.W.; Cuijpers, P. Depression and Body Mass Index, a u-Shaped Association. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupila, S.K.E.; Berntzen, B.J.; Muniandy, M.; Ahola, A.J.; Kaprio, J.; Rissanen, A.; Pietiläinen, K.H. Mental, Physical, and Social Well-Being and Quality of Life in Healthy Young Adult Twin Pairs Discordant and Concordant for Body Mass Index. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, L.S.E.; Tan, X.W.; Chong, S.A.; Vaingankar, J.A.; Abdin, E.; Shafie, S.; Chua, B.Y.; Heng, D.; Subramaniam, M. Independent and Combined Associations of Sleep Duration and Sleep Quality with Common Physical and Mental Disorders: Results from a Multi-Ethnic Population-Based Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.C.; James, E.; Henderson, L.-M.; McCall, C.; Cairney, S.A. The Influence of Emotion Regulation Strategies and Sleep Quality on Depression and Anxiety. Cortex 2023, 166, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.J.; Kwon, K.A.; Shin, J.; Park, S.; Jang, S.-I. Association between Sleep Quality and Depressive Symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 310, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheval, B.; Maltagliati, S.; Sieber, S.; Cullati, S.; Sander, D.; Boisgontier, M.P. Physical Inactivity Amplifies the Negative Association between Sleep Quality and Depressive Symptoms. Prev. Med. 2022, 164, 107233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K.; Bylsma, L.M.; Rottenberg, J. Why Might Poor Sleep Quality Lead to Depression? A Role for Emotion Regulation. Cogn. Emot. 2017, 31, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telleria-Aramburu, N.; Arroyo-Izaga, M. Risk Factors of Overweight/Obesity-Related Lifestyles in University Students: Results from the EHU12/24 Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 914–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicekli, I.; Gokce Eskin, S. High Prevalence and Co-Occurrence of Modifiable Risk Factors for Non-Communicable Diseases among University Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2025, 12, 1484164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celie, B.; Laubscher, R.; Bac, M.; Schwellnus, M.; Nolte, K.; Wood, P.; Camacho, T.; Basu, D.; Borresen, J. Poor Health Behaviour in Medical Students at a South African University: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, Z.; Zou, M.; Feng, X.; Liu, Y. Association between Daily Movement Behaviors and Optimal Physical Fitness of University Students: A Compositional Data Analysis. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, R.G.; Kandula, N.R.; Angell, S.Y.; Brewer, L.C.; Grandner, M.; Hayman, L.L.; Ing, C.; Joseph, J.J.; Moise, N.; Nelson, S.E.; et al. Implementation of Evidence-Based Behavioral Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Community Settings: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 152, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, S.; Jones, A. Is There Evidence That Walking Groups Have Health Benefits? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, K.-S.; Lee, I.; Kim, S.; Lim, C.S.; Joh, H.-K.; Park, B.-J.; Song, M.K. The Effects of a Campus Forest-Walking Program on Undergraduate and Graduate Students’ Physical and Psychological Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.J.; Yu, A.P.; Leung, C.K.; Chin, E.C.; Fong, D.Y.; Cheng, C.P.; Yau, S.Y.; Siu, P.M. Comparison of Moderate and Vigorous Walking Exercise on Reducing Depression in Middle-aged and Older Adults: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).