Temporal Evolution of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter/Eyeball Ratio on CT and MRI for Neurological Prognostication After Cardiac Arrest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

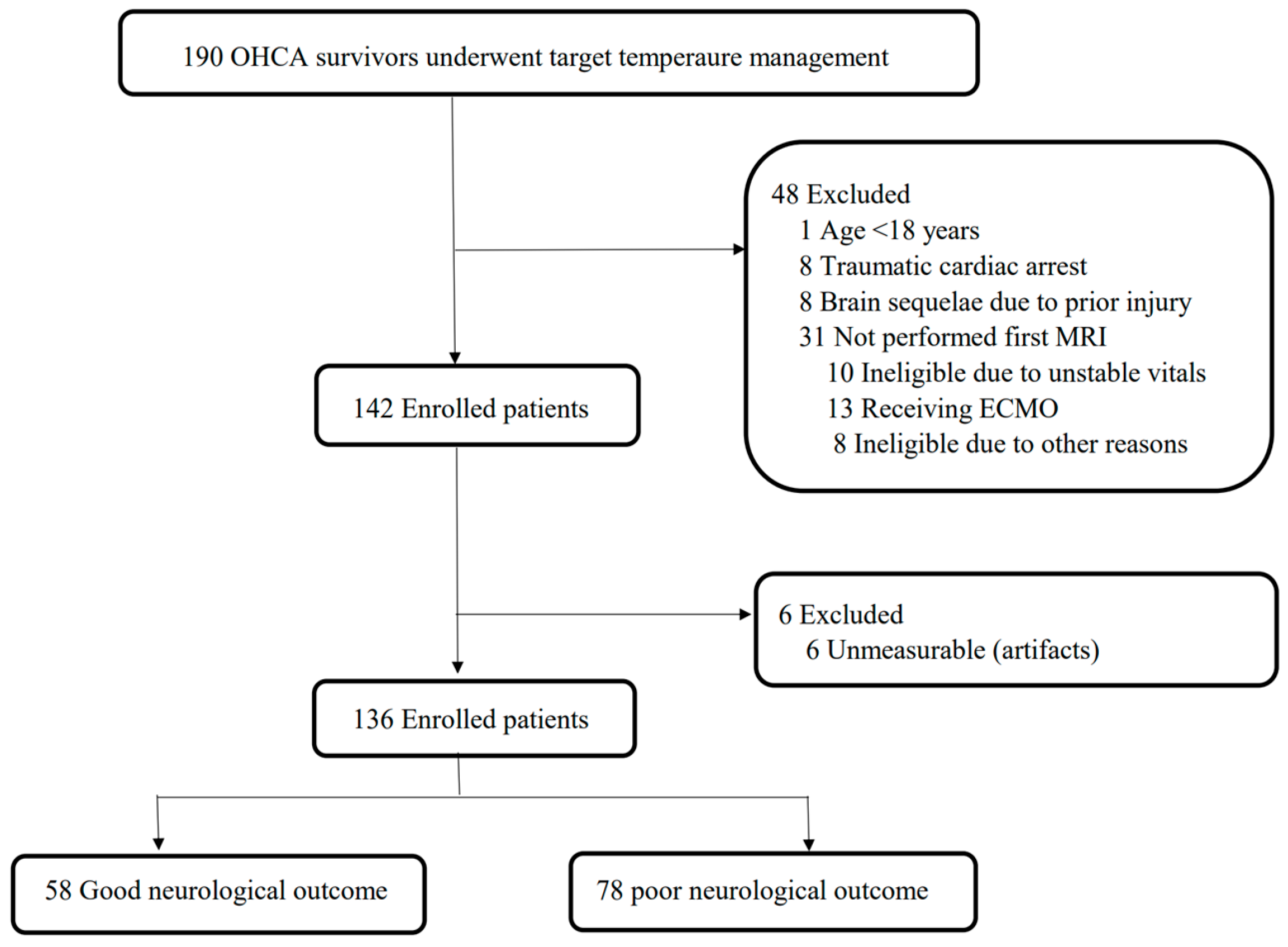

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. TTM Protocol

2.3. Data Collection

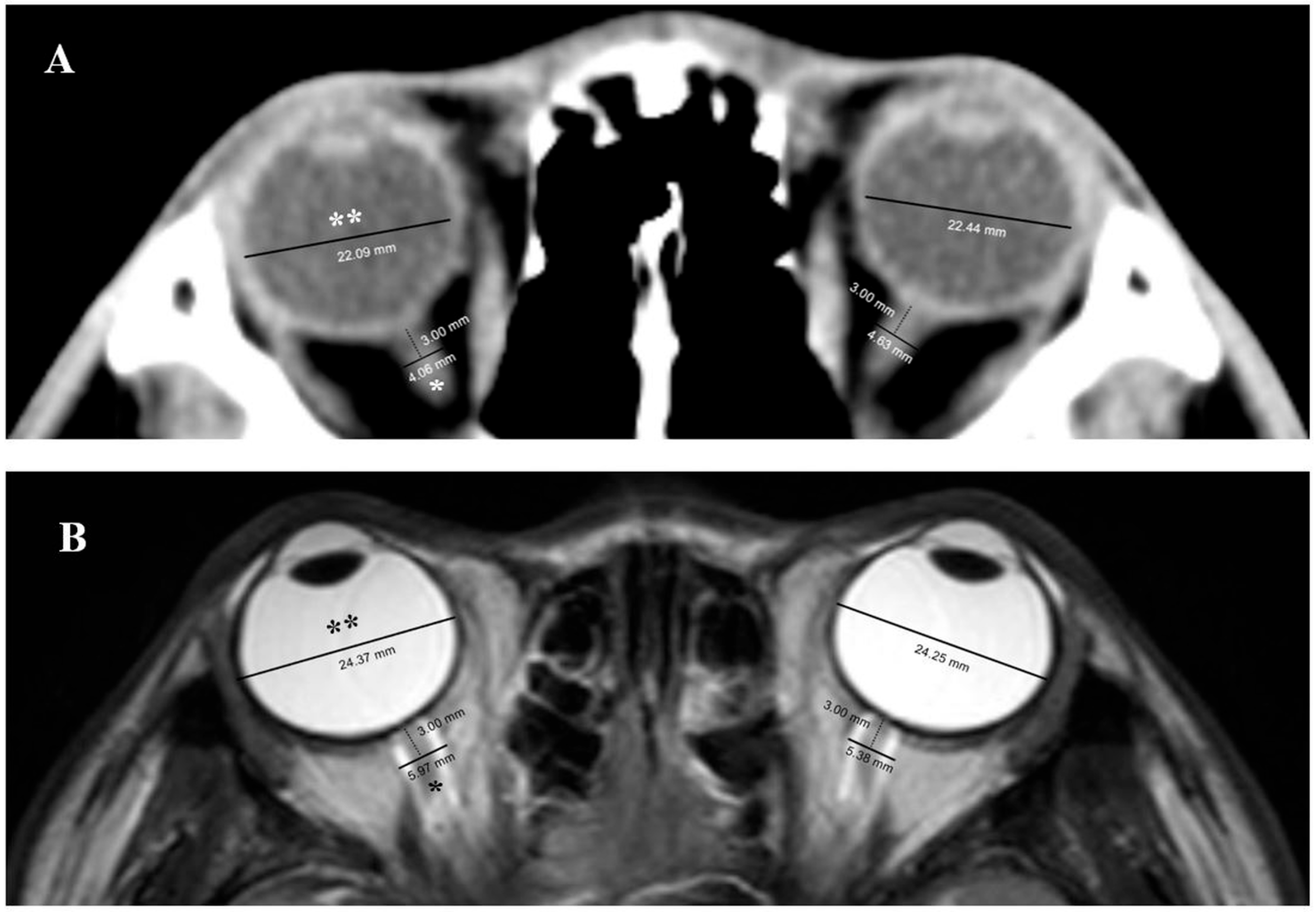

2.4. Measurement of ONSD and ETD in Brain CT and MRI

2.5. NSE Measurement

2.6. Outcomes

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Measurement of ONSD and ETD in Brain CT and MRI

3.3. ONSD and ONSD/ETD Ratios and Neurological Outcomes

3.4. Prognostic Performance of ONSD and ONSD/ETD Ratio on First and Second CT and MRI

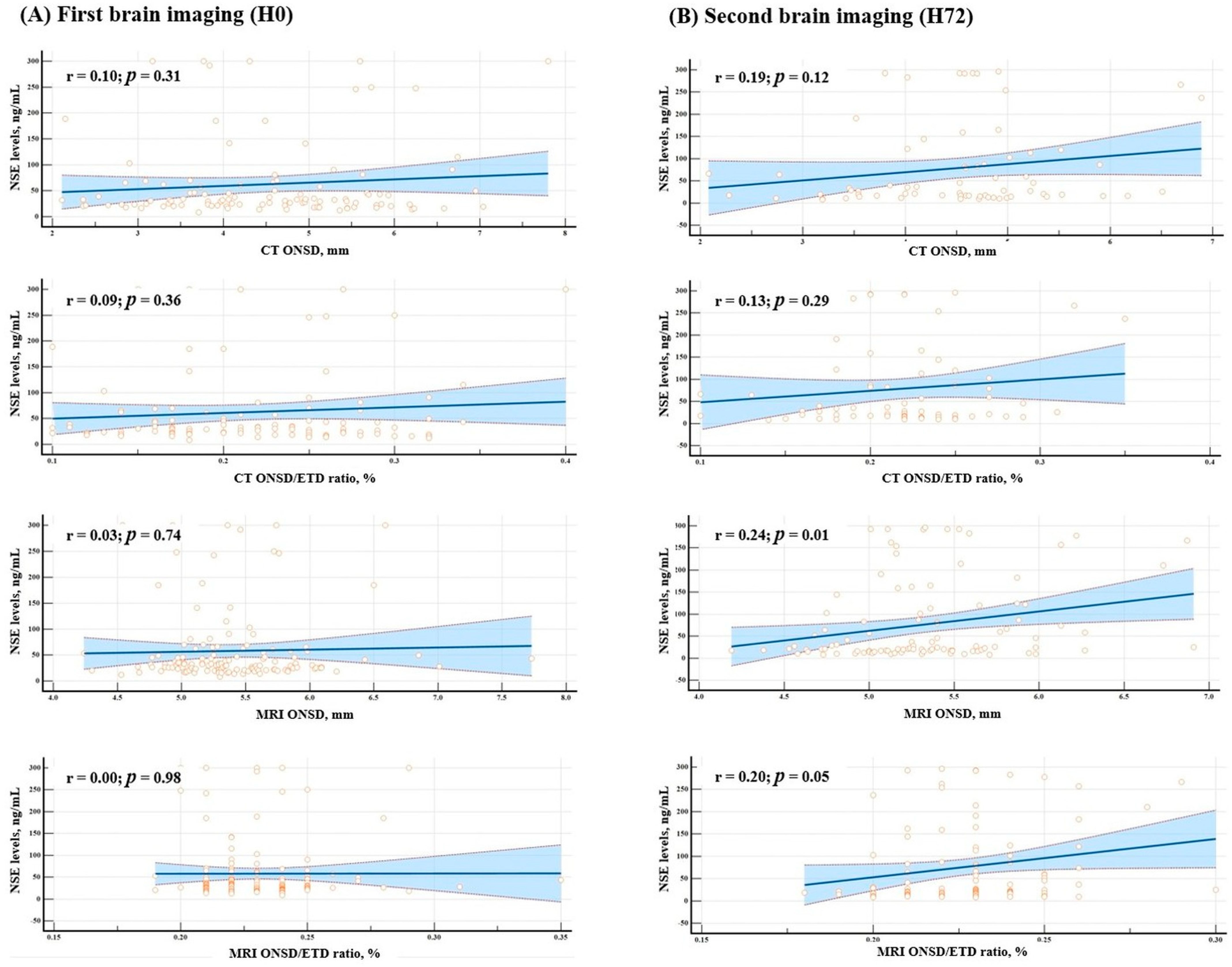

3.5. Correlation Between NSE and ONSD and ONSD/ETD Ratios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Apparent diffusion coefficient |

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CNUH | Chungnam National University Hospital |

| CPC | Cerebral performance category |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| DWI | Diffusion-weighted imaging |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| ETD | Eyeball transverse diameter |

| GWR | Gray-to-white matter ratio |

| H0 | Immediately after return of spontaneous circulation |

| H72 | 72 h after return of spontaneous circulation |

| HIBI | Hypoxic–ischemic brain injury |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficients |

| ICP | Intracranial pressure |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NPV | Negative predictive value |

| NSE | Neuron-specific enolase |

| ONSD | Optic nerve sheath diameter |

| OHCA | Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest |

| PPV | Positive predictive value |

| rCAST | Revised Cardiac Arrest Syndrome for Therapeutic hypothermia |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| ROSC | Return of spontaneous circulation |

| TTM | Targeted temperature management |

| WLST | Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy |

References

- Park, J.S.; Lee, B.K.; Ko, S.K.; Ro, Y.S. Recent status of sudden cardiac arrests in emergency medical facilities: A report from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) of Korea, 2018–2022. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2023, 10 (Suppl.), S36–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Heart Association. 2023–24 Annual Report; American Heart Association: Dallas, TX, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/about-us/2023-2024-annual-report (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Tabi, M.; Perel, N.; Taha, L.; Amsalem, I.; Hitter, R.; Maller, T.; Manassra, M.; Karmi, M.; Zacks, N.; Levy, N.; et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest—New insights and a call for a worldwide registry and guidelines. BMC Emerg. Med. 2024, 24, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, J.P.; Sandroni, C.; Böttiger, B.W.; Cariou, A.; Cronberg, T.; Friberg, H.; Genbrugge, C.; Haywood, K.; Lilja, G.; Moulaert, V.R.M.; et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines 2021: Post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 369–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buick, J.E.; Drennan, I.R.; Scales, D.C.; Brooks, S.C.; Byers, A.; Cheskes, S.; Dainty, K.N.; Feldman, M.; Verbeek, P.R.; Zhan, C.; et al. Improving temporal trends in survival and neurological outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2018, 11, e003561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Hong, W.P.; Kim, Y.S.; Park, J.; Lim, H.J. Dual-dispatch protocols and return of spontaneous circulation in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A nationwide observational study. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2024, 11, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolovski, S.S.; Lazic, A.D.; Fiser, Z.Z.; Obradovic, I.A.; Tijanic, J.Z.; Raffay, V. Recovery and survival of patients after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A literature review showcasing the big picture of intensive care unit-related factors. Cureus 2024, 16, e54827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czosnyka, M.; Pickard, J.D. Monitoring and interpretation of intracranial pressure. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2004, 75, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhon, M.S.; Griesdale, D.E.; Ainslie, P.N.; Gooderham, P.; Foster, D.; Czosnyka, M.; Robba, C.; Cardim, D. Intracranial pressure and compliance in hypoxic ischemic brain injury patients after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2019, 141, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Park, J.; Min, J.; Yoo, I.; Jeong, W.; Cho, Y.; Ryu, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Cho, S.; et al. Relationship between time-related serum albumin concentration, optic nerve sheath diameter, cerebrospinal fluid pressure, and neurological prognosis in cardiac arrest survivors. Resuscitation 2018, 131, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.S.; Cho, Y.; You, Y.; Min, J.H.; Jeong, W.; Ahn, H.J.; Kang, C.; Yoo, I.; Ryu, S.; Lee, J.; et al. Optimal timing to measure optic nerve sheath diameter as a prognostic predictor in post-cardiac arrest patients treated with targeted temperature management. Resuscitation 2019, 143, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Min, J.H.; Park, J.S.; You, Y.; Yoo, I.; Cho, Y.C.; Jeong, W.; Ahn, H.J.; Ryu, S.; Lee, J.; et al. Relationship between optic nerve sheath diameter measured by magnetic resonance imaging, intracranial pressure, and neurological outcome in cardiac arrest survivors who underwent targeted temperature management. Resuscitation 2019, 145, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Kang, C.; Park, J.; You, Y.; In, Y.; Min, J.; Jeong, W.; Cho, Y.; Ahn, H.; Kim, D. Intracranial pressure patterns and neurological outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors after targeted temperature management: A retrospective observational study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, C.; Doulis, A.E.; Gietzen, C.H.; Adler, C.; Wienemann, H.; von Stein, P.; Hoerster, R.; Koch, K.R.; Michels, G. Optic nerve sheath diameter for assessing prognosis after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. J. Crit. Care 2024, 79, 154464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, C.K.; Cho, K.W.; Yeo, J.H.; Kang, M.J.; Kim, W.Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, J.J.; Hwang, S.Y. Feasibility of optic nerve sheath diameter measured on initial brain computed tomography as an early neurologic outcome predictor after cardiac arrest. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2014, 21, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Yun, S.J. Diagnostic performance of optic nerve sheath diameter for predicting neurologic outcome in post-cardiac arrest patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2019, 138, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.; Min, J.H.; Park, J.S.; You, Y.; Jeong, W.; Ahn, H.J.; In, Y.N.; Lee, I.H.; Jeong, H.S.; Lee, B.K.; et al. Association of ultra-early diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging with neurological outcomes after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, R.J., Jr.; Schock, R.B.; Peacock, W.F. Therapeutic hypothermia is not dead, but hibernating! Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2024, 11, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, H.J.; Youn, C.S.; Sandroni, C.; Park, K.N.; Lee, B.K.; Oh, S.H.; Cho, I.S.; Choi, S.P.; Korean Hypothermia Network Investigators. Good outcome prediction after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A prospective multicenter observational study in Korea (the KORHN-PRO registry). Resuscitation 2024, 199, 110207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.K.; Min, J.H.; Park, J.S.; Kang, C.; Lee, B.K. Early identified risk factors and their predictive performance of brain death in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 56, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Lee, S.H.; Oh, J.H.; Cho, I.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Han, C.; Choi, W.J.; Sohn, Y.D.; KORHN investigators. Optic nerve sheath diameter measured using early unenhanced brain computed tomography shows no correlation with neurological outcomes in patients undergoing targeted temperature management after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2018, 128, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, B.; Wormsbecker, A.; Berger, L.; Wiskar, K.; Sekhon, M.S.; Griesdale, D.E. Optic nerve sheath diameter on computed tomography not predictive of neurological status post-cardiac arrest. CJEM 2017, 19, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.I.; Lee, H.; Shin, H.; Kim, C.; Choi, H.J.; Kang, B.S. The prognostic value of optic nerve sheath diameter/eyeball transverse diameter ratio in the neurological outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients. Medicina 2022, 58, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppler, P.J.; Gagnon, D.J.; Flickinger, K.L.; Elmer, J.; Callaway, C.W.; Guyette, F.X.; Doshi, A.; Steinberg, A.; Dezfulian, C.; Moskowitz, A.L.; et al. A multicenter, randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial of amantadine to stimulate awakening in comatose patients resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2024, 11, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaug, G.; Siewert, B.; Benfield, A.; Edelman, R.R.; Warach, S. Time course of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) abnormality in human stroke. Neurology 1997, 49, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Ford, A.L.; Vo, K.; Powers, W.J.; Lee, J.M.; Lin, W. Signal evolution and infarction risk for apparent diffusion coefficient lesions in acute ischemic stroke are both time- and perfusion-dependent. Stroke 2011, 42, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeraerts, T.; Newcombe, V.F.; Coles, J.P.; Abate, M.G.; Perkes, I.E.; Hutchinson, P.J.A.; Outtrim, J.G.; Chatfield, D.A.; Menon, D.K. Use of T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the optic nerve sheath to detect raised intracranial pressure. Crit. Care 2008, 12, R114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäuerle, J.; Schuchardt, F.; Schroeder, L.; Egger, K.; Weigel, M.; Harloff, A. Reproducibility and accuracy of optic nerve sheath diameter assessment using ultrasound compared to magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Neurol. 2013, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, J.; Held, P.; Strotzer, M.; Müller, M.; Völk, M.; Lenhart, M.; Djavidani, B.; Feuerbach, S. Magnetic resonance imaging in patients diagnosed with papilledema: A comparison of 6 different high-resolution T1- and T2(*)-weighted 3-dimensional and 2-dimensional sequences. J. Neuroimaging 2002, 12, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, A.; Jeanjean, P.; Delanghe, F.; Peltier, J.; Lecat, B.; Dupont, H. Estimation of optic nerve sheath diameter on an initial brain computed tomography scan can contribute prognostic information in traumatic brain injury patients. Crit. Care 2013, 17, R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Overall Cohort (n = 136) | Good Neurological Outcome (n = 58) | Poor Neurological Outcome (n = 78) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 59.5 (45.0–70.0) | 60.5 (44.5–68.3) | 58.5 (46.5–70.5) | 0.61 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 37 (27.2) | 10 (27.0) | 27 (73.0) | 0.02 |

| CCI | 2.5 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.25) | 3.0 (1.0–4.0) | 0.73 |

| Cardiac arrest characteristics | ||||

| Witnessed | 80 (61.1) | 48 (86.0) | 32 (41.9) | <0.001 |

| Bystander CPR | 99 (70.2) | 51 (82.5) | 48 (60.8) | <0.001 |

| Shockable rhythm | 47 (34.6) | 36 (62.1) | 11 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac etiology | 53 (39.0) | 36 (62.1) | 17 (21.8) | <0.001 |

| No flow time, median (IQR), min | 2.0 (0.0–14.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 11.0 (1.0–23.0) | <0.001 |

| Low flow time, median (IQR), min | 20.0 (10.0–30.0) | 11.0 (8.0–18.0) | 28.0 (19.8–38.3) | <0.001 |

| rCAST score | 10.5 (7.5–15.0) | 6.8 (3.4–10.0) | 13.8 (10.0–16.1) | <0.001 |

| Time to examinations, median (IQR), h | ||||

| ROSC to first CT, h | 1.3 (0.9–2.4) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) | 0.03 |

| ROSC to second CT, h | 76.1 (72.3–77.9) | 75.8 (74.4–77.6) | 76.4 (74.0–78.0) | 0.65 |

| ROSC to first MRI, h | 3.1 (2.1–4.1) | 2.7 (1.9–3.9) | 3.2 (2.1–4.2) | 0.18 |

| ROSC to second MRI, h | 77.9 (76.3–79.7) | 77.9 (75.7–79.7) | 78.0 (76.5–79.7) | 0.90 |

| Neuro-prognostication | ||||

| GWR value | 1.24 (1.19–1.30) | 1.28 (1.22–1.31) | 1.21 (1.16–1.27) | <0.001 |

| NSE levels (H0), ng/mL | 30.5 (22.3–53.5) | 24.4 (19.8–30.5) | 43.2 (28.7–83.5) | <0.001 |

| NSE levels (H72), ng/mL | 26.8 (16.8–120.0) | 17.3 (12.6–24.1) | 106.0 (32.6–262.6) | <0.001 |

| Modalities | Times | Measurement | Direction | Coefficient (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | First | Optic nerve sheath diameter | Lt | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) |

| Rt | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) | |||

| Eyeball transverse diameter | Lt | 0.75 (0.66–0.81) | ||

| Rt | 0.76 (0.68–0.82) | |||

| Second | Optic nerve sheath diameter | Lt | 0.79 (0.69–0.87) | |

| Rt | 0.86 (0.78–0.91) | |||

| Eyeball transverse diameter | Lt | 0.82 (0.74–0.88) | ||

| Rt | 0.87 (0.81–0.92) | |||

| MRI | First | Optic nerve sheath diameter | Lt | 0.80 (0.73–0.86) |

| Rt | 0.78 (0.71–0.84) | |||

| Eyeball transverse diameter | Lt | 0.77 (0.70–0.83) | ||

| Rt | 0.73 (0.64–0.80) | |||

| Second | Optic nerve sheath diameter | Lt | 0.73 (0.63–0.81) | |

| Rt | 0.74 (0.63–0.81) | |||

| Eyeball transverse diameter | Lt | 0.77 (0.69–0.84) | ||

| Rt | 0.76 (0.66–0.83) |

| Good Neurological Outcome (n = 58) | Poor Neurological Outcome (n = 78) | p-Value a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First CT, 136 b | |||

| ONSD, median (IQR, mm) | 4.44 (3.70–5.43) | 4.51 (3.53–5.47) | 0.75 |

| ONSD/ETD, median (IQR) | 0.22 (0.17–0.26) | 0.21 (0.17–0.26) | 0.83 |

| Second CT, 71 b | |||

| ONSD, median (IQR, mm) | 4.62 (3.98–5.01), 33 b | 4.57 (3.54–4.96), 38 b | 0.45 |

| ONSD/ETD, median (IQR) | 0.22 (0.20–0.25), 33 b | 0.21 (0.18–0.24), 38 b | 0.21 |

| First MRI, 136 b | |||

| ONSD, median (IQR, mm) | 5.31 (4.97–5.64) | 5.30 (5.08–5.71) | 0.68 |

| ONSD/ETD, median (IQR) | 0.23 (0.21–0.24) | 0.23 (0.22–0.24) | 0.53 |

| Second MRI, 104 b | |||

| ONSD, median (IQR, mm) | 5.12 (4.81–5.49), 52 b | 5.37 (5.17–5.74), 52 b | 0.003 |

| ONSD/ETD, median (IQR) | 0.22 (0.21–0.23), 52 b | 0.23 (0.22–0.24), 52 b | 0.01 |

| Measurement | Neurological Outcome | First CT (n = 136) | Second CT (n = 71) | p-Value a |

| ONSD, median (IQR, mm) | Good outcome | 4.44 (3.70–5.43), 58 b | 4.62 (3.98–5.01), 33 b | 0.58 |

| Poor outcome | 4.51 (3.53–5.47), 78 b | 4.57 (3.54–4.96), 38 b | 0.28 | |

| ONSD/ETD ratio, median (IQR) | Good outcome | 0.22 (0.17–0.26), 58 b | 0.22 (0.20–0.25), 33 b | 0.95 |

| Poor outcome | 0.21 (0.17–0.26), 78 b | 0.21 (0.18–0.24), 38 b | 0.52 | |

| First MRI (n = 136) | Second MRI (n = 104) | p-Value a | ||

| ONSD, median (IQR, mm) | Good outcome | 5.31 (4.97–5.64), 32 b | 5.12 (4.81–5.49), 52 b | <0.001 |

| Poor outcome | 5.30 (5.08–5.71), 44 b | 5.37 (5.17–5.74), 28 b | 0.17 | |

| ONSD/ETD ratio, median (IQR) | Good outcome | 0.23 (0.21–0.24), 58 b | 0.22 (0.21–0.23), 52 b | 0.005 |

| Poor outcome | 0.23 (0.22–0.24), 78 b | 0.23 (0.22–0.24), 52 b | 0.22 |

| Predictor | Cut-Off | AUC (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | |||||||

| First ONSD | ≤6.74 | 0.52 (0.41–0.63) | 98.5 (91.8–100) | 4.8 (0.6–16.2) | 61.9 (60.1–63.6) | 66.7 (15.8–95.5) | 0.74 |

| First ONSD/ETD | ≤0.4 | 0.51 (0.40–0.62) | 100.0 (94.6–100) | 0.0 (0.0–8.4) | 61.1 (61.1–61.1) | No data | 0.86 |

| Second ONSD | ≤4.7 | 0.55 (0.42–0.69) | 65.8 (48.6–80.4) | 48.5 (30.8–66.5) | 59.5 (49.6–68.7) | 55.2 (41.2–68.4) | 0.44 |

| Second ONSD/ETD | ≤0.21 | 0.59 (0.45–0.72) | 55.3 (38.3–71.4) | 66.7 (48.2–82.0) | 65.6 (52.1–77.0) | 56.4 (45.8–66.5) | 0.21 |

| MRI | |||||||

| First ONSD | >4.97 | 0.52 (0.42–0.62) | 88.5 (79.2–94.6) | 25.9 (15.3–39.0) | 61.6 (57.5–65.6) | 62.5 (44.0–78.0) | 0.70 |

| First ONSD/ETD | >0.19 | 0.52 (0.42–0.62) | 98.7 (93.1–100) | 1.7 (0.0–9.2) | 57.5 (56.4–58.5) | 50.0 (6.0–94.0) | 0.69 |

| Second ONSD | >5.15 | 0.67 (0.56–0.78) | 82.7 (69.7–91.8) | 53.9 (39.5–67.8) | 64.2 (56.6–71.1) | 75.7 (62.0–85.6) | 0.002 |

| Second ONSD/ETD | >0.21 | 0.65 (0.55–0.75) | 86.5 (74.2–94.4) | 42.3 (28.7–56.8) | 60.0 (53.7–66.0) | 75.9 (59.5–87.0) | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, J.; Jeon, S.-Y.; Park, J.S.; Lim, J.A.; Lee, B.K. Temporal Evolution of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter/Eyeball Ratio on CT and MRI for Neurological Prognostication After Cardiac Arrest. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6891. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196891

Choi J, Jeon S-Y, Park JS, Lim JA, Lee BK. Temporal Evolution of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter/Eyeball Ratio on CT and MRI for Neurological Prognostication After Cardiac Arrest. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6891. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196891

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Jiyoung, So-Young Jeon, Jung Soo Park, Jin A Lim, and Byung Kook Lee. 2025. "Temporal Evolution of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter/Eyeball Ratio on CT and MRI for Neurological Prognostication After Cardiac Arrest" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6891. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196891

APA StyleChoi, J., Jeon, S.-Y., Park, J. S., Lim, J. A., & Lee, B. K. (2025). Temporal Evolution of Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter/Eyeball Ratio on CT and MRI for Neurological Prognostication After Cardiac Arrest. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6891. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196891