The Psychosocial Burden of Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study of Associations Between Sleep Quality, Anxiety, and Depression in Turkish Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

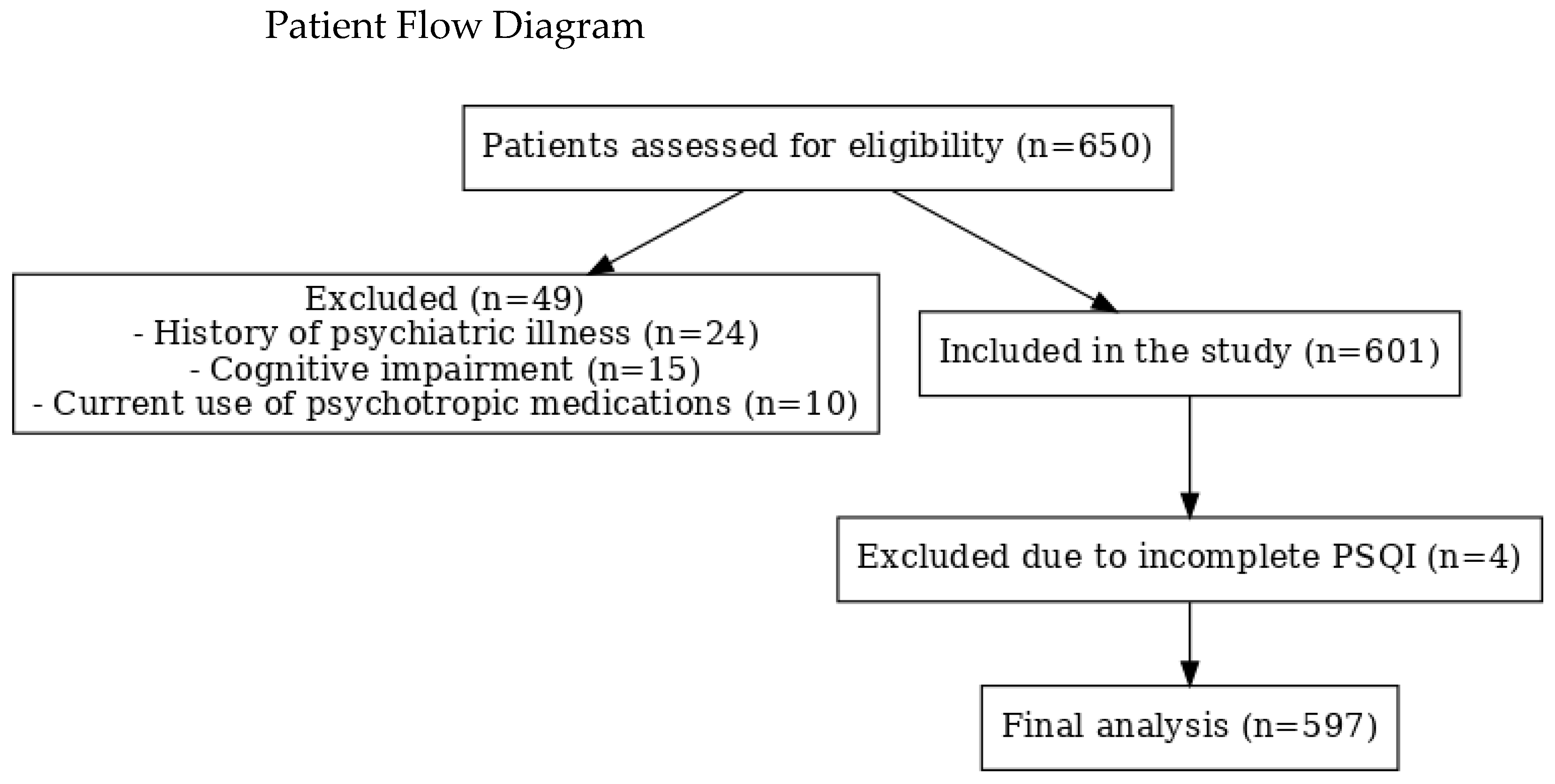

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Sleep Quality

2.3.2. Anxiety and Depression

2.3.3. Ethical Considerations

2.3.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbeck, N.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Cortes, J.; Gnant, M.; Houssami, N.; Poortmans, P.; Ruddy, K.; Tsang, J.; Cardoso, F. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorofi, S.A.; Nozari-Mirarkolaei, F.; Arbon, P.; Bagheri-Nesami, M. Depression and sleep quality among Iranian women with breast cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 3433–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Gao, J.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; Li, W. Anxiety, depression, and sleep quality among breast cancer patients in North China: Mediating roles of hope and medical social support. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Mai, Q.; Mei, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Knobf, M.T.; Ye, Z. The longitudinal association between resilience and sleep quality in breast cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 74, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Maqbali, M.; Al Sinani, M.; Alsayed, A.; Gleason, A.M. Prevalence of Sleep Disturbance in Patients With Cancer: A Sys-tematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2022, 31, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Irwin, M.R.; Olmstead, R.; Carroll, J.E. Sleep disturbance, inflammation, and depression risk in cancer survivors. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 30 (Suppl.), S58–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Kherchi, O.; Aquil, A.; Elkhoudri, N.; Guerroumi, M.; El Azmaoui, N.; Mouallif, M.; Aitbouighoulidine, S.; Chokri, A.; Benider, A.; Elgot, A. Relationship between sleep quality and anxiety-depressive disorders in Moroccan women with breast cancer: A cross-sectional study. Iran. J. Public Health 2023, 52, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; He, Y.; Yang, T.; Wu, C.; Lin, Y.; Yan, J.; Chang, W.; Chang, F.; Wang, Y.; Cao, B. Relationship of sleep-quality and social-anxiety in patients with breast cancer: A network analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buyuksimsek, M.; Gulmez, A.; Pirinci, O.; Tohumcuoglu, M.; Kidi, M.M. Are depression and poor sleep quality a major problem in Turkish women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer? Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2024, 70, e20231377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budhrani, P.H.; Lengacher, C.A.; Kip, K.E.; Tofthagen, C.S.; Jim, H.S. An integrative review of subjective and objective measures of sleep disturbances in breast cancer survivors. Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Ferguson, D.W.; Gill, J.; Paul, J.; Symonds, P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S.C.; DeMichele, A.; Schapira, M.; Glanz, K.; Blauch, A.N.; Pucci, D.A.; Jacobs, L.A. Symptoms, unmet need, and quality of life among recent breast cancer survivors. J. Community Support. Oncol. 2016, 14, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, R.; Cai, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Ji, Y.; Li, M.; Qin, Q.; Yang, Y.; Huang, D.; Pan, A.; et al. The prevalence of psychological disorders among cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Psychooncology 2022, 31, 1972–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, Z.; Ma, Z.; Mao, Y.; Li, X.; Wilson, A.; Qin, H.; Ou, J.; Peng, K.; Zhou, F.; et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhruva, A.; Paul, S.M.; Cooper, B.A.; Lee, K.; West, C.; Aouizerat, B.E.; Dunn, L.B.; Swift, P.S.; Wara, W.; Miaskowski, C. A longitudinal study of measures of objective and subjective sleep disturbance in patients with breast cancer before, during, and after radiation therapy. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2012, 44, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riba, M.B.; Donovan, K.A.; Ahmed, K.; Braun, I.M.; Breitbart, W.S.; Brewer, B.W.; Buchmann, L.O.; Clark, M.M.; Elkin, T.D.; Jacobsen, P.B.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Distress Management, Version 2.2023. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2023, 21, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treeck, O.; Buechler, C.; Ortmann, O. Chemerin and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Zhu, X.; Lin, Z.; Luo, L.; Wen, D. The potential value of serum chemerin in patients with breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | PSQI Sleep Quality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 Good n = 399 (%66.8) | >5 Bad n = 198 (%33.2) | p | ||||||

| Age Median (Min–Max) | 54 (25–83) | 54 (25–83) | 55 (34–82) | 0.464 | ||||

| BMI Median (Min–Max) | 28.9 (16.2–49.5) | 28.7 (16.2–49.5) | 29.6 (18.1–49.5) | 0.308 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p | ||

| Age | <65 | 473 | 79.2 | 320 | 80.2 | 153 | 77.3 | 0.406 |

| ≥65 | 124 | 20.8 | 79 | 19.8 | 45 | 22.7 | ||

| BMI | <25 | 124 | 20.8 | 84 | 21.1 | 40 | 20.2 | 0.809 |

| ≥25 | 473 | 79.2 | 315 | 78.9 | 158 | 79.8 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 527 | 89.3 | 353 | 89.6 | 174 | 88.8 | 0.255 |

| Single | 13 | 2.2 | 6 | 1.5 | 7 | 3.6 | ||

| Widow | 50 | 8.5 | 35 | 8.9 | 15 | 7.7 | ||

| Child status | No | 27 | 4.8 | 19 | 5.1 | 8 | 4.2 | 0.615 |

| Yes | 536 | 95.2 | 352 | 94.9 | 184 | 95.8 | ||

| Job | Housewife | 470 | 80.6 | 310 | 80.3 | 160 | 81.2 | 0.691 |

| Civil Servant | 29 | 5.0 | 21 | 5.4 | 8 | 4.1 | ||

| Worker | 55 | 9.4 | 38 | 9.8 | 17 | 8.6 | ||

| Retired | 29 | 5.0 | 17 | 4.4 | 12 | 6.1 | ||

| Chronic disease | No | 332 | 56.2 | 230 | 58.2 | 102 | 52.0 | 0.154 |

| Yes | 259 | 43.8 | 165 | 41.8 | 94 | 48.0 | ||

| Menopause status | Peri-Menopause | 261 | 43.7 | 171 | 42.9 | 90 | 45.5 | 0.547 |

| Post-Menopause | 336 | 56.3 | 228 | 57.1 | 108 | 54.5 | ||

| Smoking | Never | 447 | 77.3 | 299 | 77.5 | 148 | 77.1 | 0.944 |

| Drinks | 99 | 17.1 | 65 | 16.8 | 34 | 17.7 | ||

| Quit | 32 | 5.5 | 22 | 5.7 | 10 | 5.2 | ||

| Total | PSQI Sleep Quality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 Good n = 399 (%66.8) | >5 Bad n = 198 (%33.2) | p | ||||||

| Clinical stage | Stage 1 | 117 | 19.6 | 72 | 18.0 | 45 | 22.7 | 0.595 |

| Stage 2 | 321 | 53.8 | 219 | 54.9 | 102 | 51.5 | ||

| Stage 3 | 123 | 20.6 | 83 | 20.8 | 40 | 20.2 | ||

| Stage 4 | 36 | 6.0 | 25 | 6.3 | 11 | 5.6 | ||

| Surgery | No | 89 | 14.9 | 59 | 14.8 | 30 | 15.2 | 0.029 |

| BCS | 177 | 29.6 | 105 | 26.3 | 72 | 36.4 | ||

| MRM | 331 | 55.4 | 235 | 58.9 | 96 | 48.5 | ||

| Neoadjuvant therapy | No | 429 | 71.9 | 283 | 70.9 | 146 | 73.7 | 0.472 |

| Yes | 168 | 28.1 | 116 | 29.1 | 52 | 26.3 | ||

| Tumor localization | Right | 296 | 49.6 | 193 | 48.4 | 103 | 52.0 | 0.497 |

| Left | 292 | 48.9 | 201 | 50.4 | 91 | 46.0 | ||

| Bilateral | 9 | 1.5 | 5 | 1.3 | 4 | 2.0 | ||

| Treatment | No treatment | 94 | 15.7 | 72 | 18.0 | 22 | 11.1 | 0.182 |

| Adjuvant | 364 | 61.0 | 236 | 59.1 | 128 | 64.6 | ||

| Neoadjuvant | 59 | 9.9 | 38 | 9.5 | 21 | 10.6 | ||

| Metastatic | 80 | 13.4 | 53 | 13.3 | 27 | 13.6 | ||

| Chemotherapy | No | 57 | 9.5 | 42 | 10.5 | 15 | 7.6 | 0.248 |

| Yes | 540 | 90.5 | 357 | 89.5 | 183 | 92.4 | ||

| Radiotherapy | No | 228 | 38.2 | 157 | 39.3 | 71 | 35.9 | 0.409 |

| Yes | 369 | 61.8 | 242 | 60.7 | 127 | 64.1 | ||

| Total | PSQI Sleep Quality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤5 Good n = 399 (%66.8) | >5 Bad n = 198 (%33.2) | p | ||||||

| PSQI sleep quality Median (Min–Max) | 4 (0–19) | 3 (0–5) | 9 (6–19) | <0.001 | ||||

| Anxiety score Median (Min–Max) | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–19) | 9 (0–21) | <0.001 | ||||

| Depression score Median (Min–Max) | 5 (0–21) | 4 (0–18) | 7 (0–21) | <0.001 | ||||

| n | % | n | % | N | % | p | ||

| Diagnosis time | ≤2 years | 345 | 57.8 | 230 | 57.6 | 115 | 58.1 | 0.919 |

| >2 years | 252 | 42.2 | 169 | 42.4 | 83 | 41.9 | ||

| Habitual sleep efficiency | ≥85% | 496 | 83.1 | 392 | 98.2 | 104 | 52.5 | <0.001 |

| 75% to 84% | 33 | 5.5 | 5 | 1.3 | 28 | 14.1 | ||

| 65% to 74% | 24 | 4.0 | 2 | 0.5 | 22 | 11.1 | ||

| ≤64% | 44 | 7.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 44 | 22.2 | ||

| Sleep duration | >7 h | 432 | 72.4 | 357 | 89.5 | 75 | 37.9 | <0.001 |

| 6.0–6.9 h | 78 | 13.1 | 35 | 8.8 | 43 | 21.7 | ||

| 5.0–5.9 h | 50 | 8.4 | 5 | 1.3 | 45 | 22.7 | ||

| <5 h | 37 | 6.2 | 2 | 0.5 | 35 | 17.7 | ||

| Sleep latency | <15 min | 249 | 41.7 | 216 | 54.1 | 33 | 16.7 | <0.001 |

| 16–30 min | 185 | 31.0 | 135 | 33.8 | 50 | 25.3 | ||

| 31–60 min | 96 | 16.1 | 41 | 10.3 | 55 | 27.8 | ||

| >60 min | 67 | 11.2 | 7 | 1.8 | 60 | 30.3 | ||

| Sleep medication use | 0 | 523 | 87.6 | 382 | 95.7 | 141 | 71.2 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 20 | 3.4 | 9 | 2.3 | 11 | 5.6 | ||

| 2 | 11 | 1.8 | 4 | 1.0 | 7 | 3.5 | ||

| 3 | 43 | 7.2 | 4 | 1.0 | 39 | 19.7 | ||

| Daytime dysfunction | 0 | 491 | 82.2 | 368 | 92.2 | 123 | 62.1 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 54 | 9.0 | 24 | 6.0 | 30 | 15.2 | ||

| 2 | 33 | 5.5 | 6 | 1.5 | 27 | 13.6 | ||

| 3 | 19 | 3.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 18 | 9.1 | ||

| Subjective sleep quality | 0 | 177 | 29.6 | 162 | 40.6 | 15 | 7.6 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 284 | 47.6 | 215 | 53.9 | 69 | 34.8 | ||

| 2 | 103 | 17.3 | 21 | 5.3 | 82 | 41.4 | ||

| 3 | 33 | 5.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 32 | 16.2 | ||

| Sleep disturbance | 0 | 11 | 1.8 | 11 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 249 | 41.7 | 223 | 55.9 | 26 | 13.1 | ||

| 2 | 264 | 44.2 | 158 | 39.6 | 106 | 53.5 | ||

| 3 | 73 | 12.2 | 7 | 1.8 | 66 | 33.3 | ||

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR | 95% C.I | p | OR | 95% C.I | ||

| Age | 0.438 | 1.006 | 0.991–1.021 | 0.214 | 1.020 | 0.988–1.053 | |

| BMI | 0.307 | 1.017 | 0.985–1.050 | 0.609 | 1.011 | 0.970–1.054 | |

| Marital status (Ref: Married) | 0.274 | 0.034 | |||||

| Single | 0.127 | 2.367 | 0.784–7.149 | 0.020 | 13.29 | 1.494–118.26 | |

| Widow | 0.664 | 0.869 | 0.462–1.635 | 0.242 | 0.628 | 0.289–1.368 | |

| Having children (Ref: No) | Yes | 0.616 | 1.241 | 0.533–2.890 | 0.015 | 8.499 | 1.505–47.99 |

| Occupation (Ref: Housewife) | 0.693 | 0.711 | |||||

| Civil servant | 0.477 | 0.738 | 0.320–1.703 | 0.887 | 1.074 | 0.399–2.891 | |

| Worker | 0.642 | 0.867 | 0.474–1.584 | 0.738 | 0.879 | 0.414–1.869 | |

| Retired | 0.421 | 1.368 | 0.638–2.934 | 0.268 | 1.721 | 0.659–4.495 | |

| Chronic disease (Ref: No) | Yes | 0.154 | 1.285 | 0.910–1.813 | 0.539 | 1.153 | 0.732–1.817 |

| Menopausal status (Ref: Peri-) | Post- | 0.547 | 0.900 | 0.639–1.268 | 0.279 | 0.688 | 0.350–1.353 |

| Smoking (Ref: Non-smoker) | 0.944 | 0.585 | |||||

| Smoker | 0.814 | 1.057 | 0.668–1.673 | 0.440 | 0.798 | 0.450–1.415 | |

| Quit | 0.829 | 0.918 | 0.424–1.989 | 0.436 | 0.695 | 0.278–1.735 | |

| Stage at survey (Ref: Stage 1) | 0.596 | 0.984 | |||||

| Stage 2 | 0.191 | 0.745 | 0.480–1.158 | 0.885 | 0.957 | 0.526–1.740 | |

| Stage 3 | 0.337 | 0.771 | 0.454–1.310 | 0.867 | 1.067 | 0.501–2.271 | |

| Stage 4 | 0.390 | 0.704 | 0.316–1.568 | 0.977 | 1.023 | 0.212–4.947 | |

| Surgery (Ref: MRM) | 0.029 | 0.056 | |||||

| None | 0.390 | 1.245 | 0.755–2.051 | 0.526 | 1.661 | 0.347–7.960 | |

| BCS | 0.008 | 1.679 | 1.145–2.461 | 0.022 | 1.887 | 1.098–3.243 | |

| Treatment (Ref: No treatment) | 0.189 | 0.245 | |||||

| Adjuvant | 0.032 | 1.775 | 1.051–2.997 | 0.068 | 1.853 | 0.956–3.592 | |

| Neoadjuvant | 0.105 | 1.809 | 0.884–3.699 | 0.824 | 1.232 | 0.195–7.775 | |

| Metastatic | 0.132 | 1.667 | 0.857–3.243 | 0.881 | 1.083 | 0.382–3.067 | |

| History of chemotherapy (Ref: No) | Yes | 0.250 | 1.435 | 0.775–2.657 | 0.559 | 1.276 | 0.564–2.886 |

| History of radiotherapy (Ref: No) | Yes | 0.409 | 1.160 | 0.815–1.652 | 0.820 | 0.934 | 0.517–1.687 |

| Currently receiving chemotherapy (Ref: No) | Yes | 0.287 | 1.220 | 0.846–1.759 | 0.370 | 1.347 | 0.702–2.583 |

| Anxiety score | <0.001 | 1.235 | 1.177–1.295 | <0.001 | 1.216 | 1.141–1.295 | |

| Depression score | <0.001 | 1.165 | 1.114–1.218 | 0.093 | 1.057 | 0.991–1.127 | |

| Time from diagnosis to survey | 0.182 | 1.035 | 0.984–1.088 | 0.353 | 1.036 | 0.962–1.116 | |

| Anxiety Score | Depression Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Min–Max) | p | Median (Min–Max) | p | ||

| Age | <65 years | 6 (0–21) | 0.182 | 5 (0–21) | 0.715 |

| ≥65 years | 6 (0–18) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| Marital status | Married | 6 (0–21) | 0.049 | 5 (0–21) | 0.144 |

| Single | 9 (4–16) a | 5 (1–14) | |||

| Widow | 6 (0–21) | 6 (0–19) | |||

| Having children | No | 7 (0–17) | 0.094 | 4 (0–16) | 0.929 |

| Yes | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–21) | |||

| Occupation | Housewife | 6 (0–21) | 0.779 | 5 (0–21) | 0.678 |

| Civil servant | 7 (0–15) | 5 (0–13) | |||

| Worker | 6 (0–18) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| Retired | 6 (1–17) | 4 (0–20) | |||

| BMI | <25 | 6 (0–21) | 0.084 | 4 (0–21) | 0.298 |

| ≥25 | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| Chronic disease | No | 6 (0–21) | 0.882 | 5 (0–21) | 0.565 |

| Yes | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| Menopausal status | Pre- | 7 (0–21) | <0.001 | 5 (0–21) | 0.808 |

| Post- | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| Smoking | Non-smoker | 6 (0–21) | 0.086 | 5 (0–20) | 0.895 |

| Smoker | 7 (0–21) | 4 (0–21) | |||

| Quit | 7 (1–18) | 6 (0–16) | |||

| Clinik stage | Stage 1 | 6 (0–19) | 0.636 | 5 (0–20) | 0.231 |

| Stage 2 | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–21) | |||

| Stage 3 | 6 (0–19) | 5 (0–17) | |||

| Stage 4 | 6 (2–18) | 7 (0–20) | |||

| Surgery | None | 6 (0–21) | 0.869 | 6 (0–21) | 0.330 |

| BCS | 6 (0–19) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| MRM | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| Treatment | No treatment | 5 (0–18) | 0.015 | 5 (0–20) | 0.150 |

| Adjuvant | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| Neoadjuvant | 6 (0–21) | 6 (0–1) | |||

| Metastatic | 6 (1–21) b | 6 (0–20) | |||

| History of chemotherapy | No | 6 (1–18) | 0.456 | 4 (0–14) | 0.025 |

| Yes | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–21) | |||

| History of radiotherapy | No | 6 (0–21) | 0.439 | 5 (0–21) | 0.492 |

| Yes | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–20) | |||

| Currently receiving chemotherapy | No | 6 (0–19) | 0.252 | 5 (0–20) | 0.028 |

| Yes | 6 (0–21) | 6 (0–21) | |||

| Diagnosis to survey time | ≤2 years | 6 (0–21) | 0.941 | 5 (0–21) | 0.775 |

| >2 years | 6 (0–21) | 5 (0–20) |

| PSQI Global Score | HADS-Anxiety (HADS-A) | HADS-Depression (HADS-D) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSQI Global Score | r = 0.390, p < 0.001 | r = 0.255, p < 0.001 | |

| HADS-Anxiety (HADS-A) | r = 0.390, p < 0.001 | r = 0.592, p < 0.001 | |

| HADS-Depression (HADS-D) | r = 0.255, p < 0.001 | r = 0.592, p < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acar, Ö.; Goksel, G.; Ozan, E.; Altunbaş, A.A.; Karakaya, M.S.; Ekinci, F.; Erdoğan, A.P. The Psychosocial Burden of Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study of Associations Between Sleep Quality, Anxiety, and Depression in Turkish Women. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6773. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196773

Acar Ö, Goksel G, Ozan E, Altunbaş AA, Karakaya MS, Ekinci F, Erdoğan AP. The Psychosocial Burden of Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study of Associations Between Sleep Quality, Anxiety, and Depression in Turkish Women. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(19):6773. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196773

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcar, Ömer, Gamze Goksel, Erol Ozan, Ahmet Anıl Altunbaş, Mustafa Serkan Karakaya, Ferhat Ekinci, and Atike Pınar Erdoğan. 2025. "The Psychosocial Burden of Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study of Associations Between Sleep Quality, Anxiety, and Depression in Turkish Women" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 19: 6773. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196773

APA StyleAcar, Ö., Goksel, G., Ozan, E., Altunbaş, A. A., Karakaya, M. S., Ekinci, F., & Erdoğan, A. P. (2025). The Psychosocial Burden of Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study of Associations Between Sleep Quality, Anxiety, and Depression in Turkish Women. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(19), 6773. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14196773