Wired for Intensity: The Neuropsychological Dynamics of Borderline Personality Disorders—An Integrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- review studies that explain the neuropsychological processes of BPD, particularly focusing on emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, interpersonal dysfunction and self-harm and

- to determine the existing knowledge gaps and suggest potential future studies that will allow a more complete understanding of the disorder.

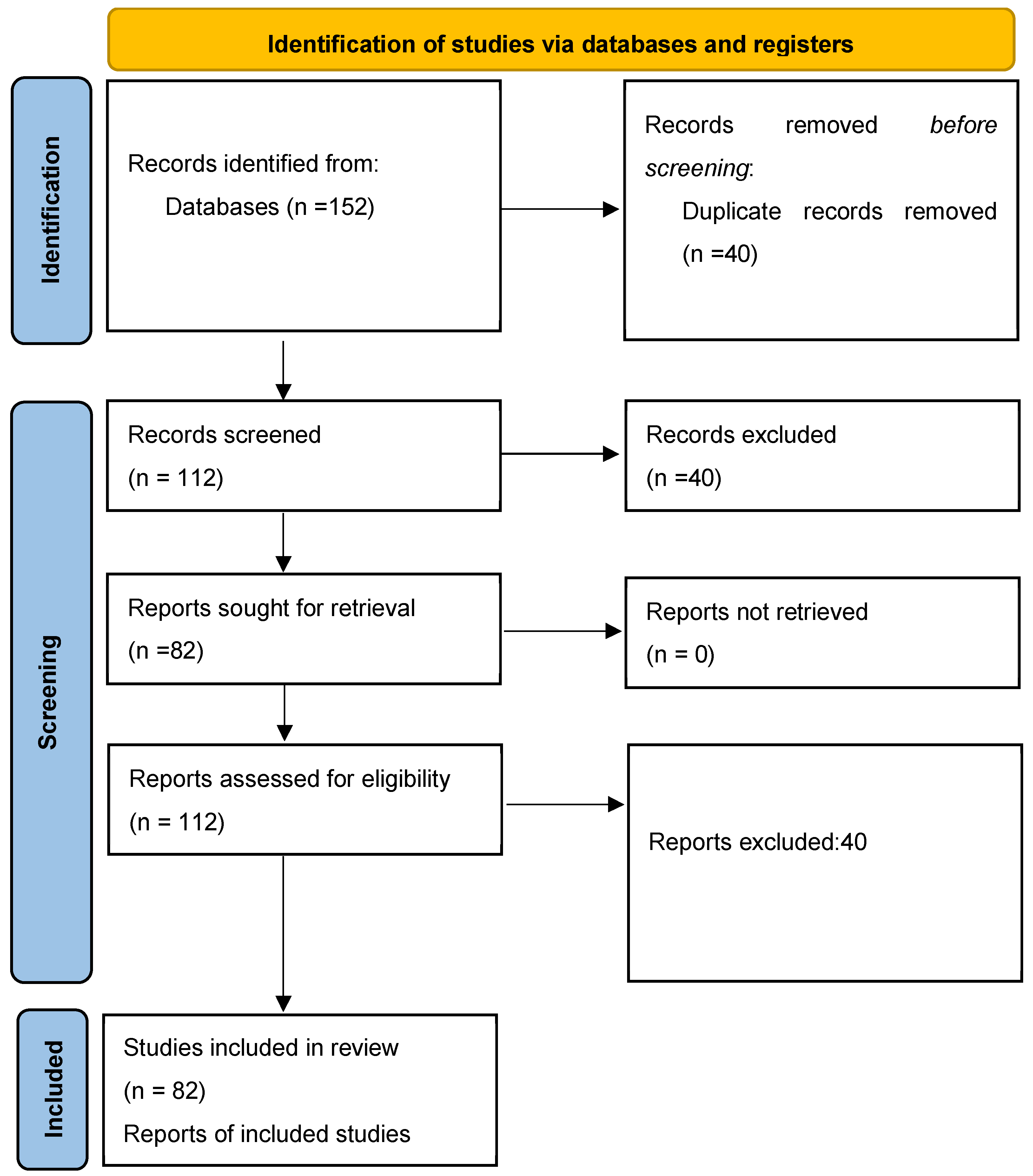

2. Methodology

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

- The study must address neuropsychological, neurobiological, or psychophysiological processes in BPD.

- It must be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

- Studies with adolescent, adult, or mixed samples were eligible.

- Both clinical trials and observational studies were included.

- Exclusion criteria were:

- Studies focusing solely on pharmacological outcomes without reference to underlying neuropsychology.

- Non-English publications.

- Grey literature, dissertations, or conference abstracts were also excluded.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Neuropsychological Symptom Domains of BPD

3.1. Diagnostic Criteria

3.2. Core Symptoms

3.2.1. Emotional Dysregulation

3.2.2. Impulsivity

3.2.3. Interpersonal Dysfunction

3.2.4. Self-Harm

3.3. Comorbidity

3.4. Functional Impairments

4. Neuropsychological Foundations of BPD

4.1. Emotional Dysregulation

4.2. Impulsivity and Behavioral Dyscontrol

4.3. Interpersonal Dysfunction

4.4. Self-Harm

4.5. Pain Modulation and Reward Mechanisms

4.6. Emotional Dysregulation and Neural Dysfunctions

4.7. Trauma, Stress Response, and Neural Plasticity

4.8. Oxytocin and Social Neuropsychology

4.9. Behavioral Reinforcement and Habit Formation

5. Treatment Considerations

5.1. Pharmacotherapy

5.2. Neuromodulation Techniques

5.3. Psychotherapeutic Interventions

6. Advances in Neuroimaging and Psychophysiological Research

7. Neurodevelopmental Perspectives

7.1. Early-Life Adversity and the Brain

7.2. Developmental Trajectories

7.3. Gene–Environment Interactions

7.4. Clinical Implications

8. Implications for Clinical Practice

8.1. Pharmacological Approaches

8.2. Neuromodulation

| Treatment Modality | Primary Symptom Domain | Evidence Strength | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) | Emotional dysregulation, self-harm | Strong | [38,48] |

| 2. Unified Protocol for Adolescents (UP-A) | Emotional dysregulation | Moderate | [7] |

| 3. Mentalization-Based Therapy (MBT) | Mentalization deficits, interpersonal dysfunction | Moderate | [49] |

| 4. Transference-Focused Psychotherapy (TFP) | Attachment-related affect regulation | Emerging | [50] |

| 5. EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) | Trauma-linked emotional dysregulation | Emerging | [51] |

| 6. Pharmacotherapy (SSRIs, mood stabilizers, naltrexone) | Affective instability, impulsivity | Moderate | [36,52] |

| 7. Neuromodulation (TMS, Neurofeedback) | Impaired prefrontal regulation | Emerging | [46,47] |

9. Future Research Directions

9.1. New Technologies in Neuropsychology

9.2. Personalized Treatment Approaches

9.3. Longitudinal Studies

9.4. Increasing Trauma Research

9.5. Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Research

9.6. Innovation in Therapeutic Modalities

9.7. Advocacy and Stigma Reduction

- What are the effects of clinician-focused anti-stigma interventions on diagnostic accuracy and treatment engagement for BPD?

- 2.

- How does public stigma around BPD compare to that of other psychiatric disorders, and what factors mediate these attitudes?

- 3.

- Can digital or narrative-based campaigns (e.g., patient storytelling, VR empathy training) reduce stigma and improve attitudes toward individuals with BPD among the general public and healthcare trainees?

9.8. Integration of Neuroscience and Psychotherapy

9.9. Psychoanalysis and Neuropsychology in BPD

9.9.1. Emotional Dysregulation and Early Object Relations

9.9.2. Impulsivity and the Ego’s Structural Weakness

9.9.3. Interpersonal Dysfunction and Attachment Theory

9.9.4. Self-Injury and Primitive Defense Mechanisms

9.9.5. Trauma, Regression and the HPA Axis

9.9.6. Perspectives Integration

Mentalizing and Prefrontal Cognitive Functions

Trauma and Neural Plasticity

9.9.7. Symbolization and Neural Integration

10. Discussion

10.1. Digital Innovations in DBT and Emotion Regulation

10.2. Current Gaps and Controversies

10.3. Limitations

11. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPD | Borderline Personality Disorder |

| APA | American Psychiatric Association |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

| ICD-11 | International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision |

| CM | Childhood Maltreatment |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| DMN | Default Mode Network |

| NSSI | Non-Suicidal Self-Injury |

| HPA axis | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis |

| UP-A | Unified Protocol for Adolescents |

| MBT-A | Mentalization-Based Therapy for Adolescents |

| DBT | Dialectical Behavior Therapy |

| TFP | Transference-Focused Psychotherapy |

| MBT | Mentalization-Based Therapy |

| EMDR | Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing |

| TF-CBT | Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| SSRIs | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors |

| TMS | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| tDCS | Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| fMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DTI | Diffusion Tensor Imaging |

| HRV | Heart Rate Variability |

| 5-HTTLPR | Serotonin-Transporter-Linked Polymorphic Region |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; (DSM-5); APA: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring, F.; Fonagy, P.; Heim, N.; Kernberg, O.F.; Leweke, F.; Luyten, P.; Salzer, S.; Spitzer, C.; Steinert, C. Borderline personality disorder: A comprehensive review of diagnosis and clinical presentation, etiology, treatment, and current controversies. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grant, B.F.; Chou, S.P.; Goldstein, R.B.; Huang, B.; Stinson, F.S.; Saha, T.D.; Smith, S.M.; Dawson, D.A.; Pulay, A.J.; Pickering, R.P.; et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunderson, J.G.; Stout, R.L.; McGlashan, T.H.; Shea, M.T.; Morey, L.C.; Grilo, C.M.; Zanarini, M.C.; Yen, S.; Markowitz, J.C.; Sanislow, C.; et al. Ten-year course of borderline personality disorder: Psychopathology and function from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clemmensen, L.M.Ø.; Jensen, S.O.W.; Zanarini, M.C.; Skadhede, S.; Munk-Jørgensen, P. Changes in treated incidence of borderline personality disorder in Denmark: 1970–2009. Can. J. Psychiatry 2013, 58, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilé, J.M.; Boissel, L.; Alaux-Cantin, S.; de La Rivière, S.G. Borderline personality disorder in adolescents: Prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment strategies. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2018, 9, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerin, B.; Gallagher, M.W.; Howard, R. Unified Protocol vs Mentalization-Based Therapy for Adolescents With Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2025, 32, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Lin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Xu, L.; Tang, X.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Q.; Wang, J.; et al. Age-related differences in borderline personality disorder traits and childhood maltreatment: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1454328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino-Pettit, A.; Gilbert, K.; Boone, K.; Luking, K.; Geselowitz, B.; Tillman, R.; Whalen, D.; Luby, J.; Barch, D.M.; Vogel, A. Associations of Child Amygdala Development with Borderline Personality Symptoms in Adolescence. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Wang, S.; Qin, K.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lai, H.; Suo, X.; Long, Y.; Gong, Q.; et al. Common and distinct neural patterns of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and borderline personality disorder: A multimodal functional and structural meta-analysis. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2023, 8, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenyer, B.F.S.; Day, N.J.S.; Denmeade, G.; Ciarla, A.; Davy, K.; Reis, S.; Townsend, M. AIR therapy: A pilot study of a clinician-assisted e-therapy for adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Borderline Pers. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2025, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P. A developmental, mentalization-based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 1355–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, B.; Kramer, U.; Doering, S.; di Giacomo, E.; Hutsebaut, J.; Kaera, A.; De Panfilis, C.; Schmahl, C.; Swales, M.; Taubner, S.; et al. The ICD-11 classification of personality disorders: A European perspective on challenges and opportunities. Borderline Pers. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2022, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmahl, C.; Bremner, J.D. Neuroimaging in borderline personality disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2006, 40, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, A.; Jacob, G.; Lieb, K.; Tüscher, O. Impulsivity in borderline personality disorder: A matter of disturbed impulse control or a facet of emotional dysregulation? Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2013, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preißler, S.; Dziobek, I.; Ritter, K.; Heekeren, H.R.; Roepke, S. Social cognition in borderline personality disorder: Evidence for disturbed recognition of the emotions, thoughts, and intentions of others. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B.; Sher, L.; Wilson, S.; Ekman, R.; Huang, Y.-.Y.; Mann, J.J. Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior, endogenous opioids and monoamine neurotransmitters. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 124, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Klonsky, E.D. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanarini, M.C.; Frankenburg, F.R.; Hennen, J.; Reich, D.B.; Silk, K.R. Axis I comorbidity in patients with borderline personality disorder: 6-year follow-up and prediction of time to remission. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 2108–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trull, T.J.; Sher, K.J.; Minks-Brown, C.; Durbin, J.; Burr, R. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000, 20, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, S.; Almari, R.; Khattab, K.; Badr, A.; Balawi, A.R.; Haddad, R.; Almasri, R.; Varrassi, G. Borderline Personality Disorder: A Comprehensive Review of Current Diagnostic Practices, Treatment Modalities, and Key Controversies. Cureus 2024, 16, e75893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbersweig, D.; Clarkin, J.F.; Goldstein, M.; Kernberg, O.F.; Tuescher, O.; Levy, K.N.; Brendel, G.; Pan, H.; Beutel, M.; Pavony, M.T.; et al. Failure of frontolimbic inhibitory function in the context of negative emotion in borderline personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 1832–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Ibrahim, G.M.; Venetucci Gouveia, F. Molecular Pathways, Neural Circuits and Emerging Therapies for Self-Injurious Behaviour. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- New, A.S.; Triebwasser, J.; Charney, D.S. The case for shifting borderline personality disorder to Axis I. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 64, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlin, H.A.; Rolls, E.T.; Iversen, S.D. Borderline personality disorder, impulsivity, and the orbitofrontal cortex. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 2360–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M.; Brunner, R.; Chanen, A. Borderline personality disorder in adolescence. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 782–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parr, A.C.; Calancie, O.G.; Coe, B.C.; Khalid-Khan, S.; Munoz, D.P. Impulsivity and Emotional Dysregulation Predict Choice Behavior During a Mixed-Strategy Game in Adolescents With Borderline Personality Disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 667399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bartz, J.A.; Zaki, J.; Bolger, N.; Ochsner, K.N. Social effects of oxytocin in humans: Context and person matter. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A.Z.; Aljabari, R.; Dalrymple, K.; Zimmerman, M. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury and Suicide: Differences Between Those With and Without Borderline Personality Disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 2020, 34, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, D.; Patrick, C.J.; Kennealy, P.J. Role of serotonin and dopamine system interactions in the neurobiology of impulsive aggression and its comorbidity with other clinical disorders. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2008, 13, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingenfeld, K.; Spitzer, C.; Rullkötter, N.; Löwe, B. Borderline personality disorder: Hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis and findings from neuroimaging studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teicher, M.H.; Dumont, N.L.; Ito, Y.; Vaituzis, C.; Giedd, J.N.; Andersen, S.L. Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 56, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrehumbert, B.; Torrisi, R.; Laufer, D.; Halfon, O.; Ansermet, F.; Popovic, M.B. Oxytocin response to an experimental psychosocial challenge in adults exposed to traumatic experiences during childhood or adolescence. Neuroscience 2010, 166, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriani, A.; Zhou, X.; Del Giovane, C.; E Hetrick, S.; Qin, B.; Whittington, C.; Coghill, D.; Zhang, Y.; Hazell, P.; Leucht, S.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: A network meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschentscher, N.; Tafelmaier, J.C.; Woll, C.F.; Pogarell, O.; Maywald, M.; Vierl, L.; Breitenstein, K.; Karch, S. The clinical impact of real-time fMRI neurofeedback on emotion regulation: A systematic review. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, M.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, D.; Ross, C.A. Application of EMDR Therapy to Self-Harming Behaviors. J. EMDR Pract. Res. 2016, 10, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, L.; Schmahl, C.; Niedtfeld, I. Neural Correlates of Disturbed Emotion Processing in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Multimodal Meta-Analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2016, 79, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozzatello, P.; Rocca, P.; Baldassarri, L.; Bosia, M.; Bellino, S. The Role of Trauma in Early Onset Borderline Personality Disorder: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. Front Psychiatry. 2021, 12, 721361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crone, E.A.; Dahl, R.E. Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distel, M.A.; Trull, T.J.; Derom, C.A.; Thiery, E.W.; Grimmer, M.A.; Martin, N.G.; Willemsen, G.; Boomsma, D.I. Heritability of borderline personality disorder features is similar across three countries. Psychol. Med. 2008, 38, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Postovit, L.; Cattaneo, A.; Binder, E.B.; Aitchison, K.J. Epigenetic Modifications in Stress Response Genes Associated With Childhood Trauma. Front. Psychiatry. 2019, 10, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hankin, B.L.; Nederhof, E.; Oppenheimer, C.W.; Jenness, J.; Young, J.F.; Abela, J.R.; Smolen, A.; Ormel, J.; Oldehinkel, A.J. Differential susceptibility in youth: Evidence that 5-HTTLPR x positive parenting is associated with positive affect ‘for better and worse’. Transl. Psychiatry 2011, 1, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Feffer, K.; Lee, H.H.; Wu, W.; Etkin, A.; Demchenko, I.; Cairo, T.; Mazza, F.; Fettes, P.; Mansouri, F.; Bhui, K.; et al. Dorsomedial prefrontal rTMS for depression in borderline personality disorder: A pilot randomized crossover trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 301, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehler, D.M.; Sokunbi, M.O.; Habes, I.; Barawi, K.; Subramanian, L.; Range, M.; Evans, J.; Hood, K.; Lührs, M.; Keedwell, P.; et al. Targeting the affective brain—a randomized controlled trial of real-time fMRI neurofeedback in patients with depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 2578–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, M.; Carpenter, D.; Tang, C.Y.; Goldstein, K.E.; Avedon, J.; Fernandez, N.; Mascitelli, K.A.; Blair, N.J.; New, A.S.; Triebwasser, J.; et al. Dialectical behavior therapy alters emotion regulation and amygdala activity in patients with borderline personality disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 57, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Bateman, A.W. Mechanisms of change in mentalization-based treatment of BPD. J. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 62, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, F.E. Transference-focused psychotherapy in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr. Ann. 2004, 34, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafkemeijer, L.; de Jongh, A.; Starrenburg, A.; Hoekstra, T.; Slotema, K. EMDR treatment in patients with personality disorders. Should we fear symptom exacerbation? Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2024, 15, 2407222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.C.; Arias, L.; Soler, J. Pharmacological Management of Borderline Personality Disorder and Common Comorbidities. CNS Drugs. 2023, 37, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nenadić, I.; Katzmann, I.; Besteher, B.; Langbein, K.; Güllmar, D. Diffusion tensor imaging in borderline personality disorder showing prefrontal white matter alterations. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 101, 152172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, M.; Yoo, H.J.; Nga, L.; Lee, T.H.; Thayer, J.F.; Mather, M. Heart rate variability is associated with amygdala functional connectivity with MPFC across younger and older adults. Neuroimage 2016, 139, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martín-Blanco, A.; Soler, J.; Villalta, L.; Feliu-Soler, A.; Elices, M.; Pérez, V.; Arranz, M.J.; Ferraz, L.; Alvarez, E.; Pascual, J.C. Exploring the interaction between childhood maltreatment and temperamental traits on the severity of borderline personality disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi-Kain, L.W.; Finch, E.F.; Masland, S.R.; Jenkins, J.A.; Unruh, B.T. What works in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2017, 4, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhakhan, F.; Blake, H.; Hett, D.; Marwaha, S. Efficacy of digital technologies aimed at enhancing emotion regulation skills: Literature review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 809332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviram, R.B.; Brodsky, B.S.; Stanley, B. Borderline personality disorder, stigma and treatment implications. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commons Treloar, A.J.; Lewis, A.J. Professional attitudes towards deliberate self-harm in patients with borderline personality disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2008, 42, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M. Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. J. Psychother. Pract. Res. 1996, 5, 160. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg, O.F. Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism; Jason Aronson: Lanham, MD, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P.; Gergely, G.; Jurist, E.J.; Target, M. Affect Regulation, Mentalization, and the Development of the Self; Other Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, S. The ego and the id. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud; Strachey, J., Ed.; Strachey, J., Translator; Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1961; Volume 19, pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W. The theory of the parent-infant relationship. In The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment; Laia: Barcelona, Spain, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Br. J. Psychiatry 1988, 153, 721. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W. The Family and Individual Development; Routledge: London, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, R.C.; Sambataro, F.; Vasic, N.; Schmid, M.; Thomann, P.A.; Bienentreu, S.D.; Wolf, N.D. Aberrant connectivity of resting-state networks in borderline personality disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2011, 36, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, B.; Siever, L.J. The interpersonal dimension of borderline personality disorder: Toward a neuropeptide model. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. Beyond the pleasure principle. Psychoanal. Hist. 2015, 17, 151–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zutphen, C.P. The Emotional Rollercoaster Called Borderline Personality Disorder: Neural Correlates of Emotion Regulation and Impulsivity. Ph.D. Thesis, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, A. Trauma, Reverie, and The Field. Psychoanal. Q. 2006, 75, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bion, W.; Hinshelwood, R. Learning from Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Teicher, M.H.; Samson, J.A. Annual research review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, A.W. Mentalization-Based Treatment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Utz, A.; Winter, D.; Niedtfeld, I.; Schmahl, C. The latest neuroimaging findings in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Domain | Neural Correlate | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Dysregulation | Amygdala hyperactivity, PFC hypoactivity | Reduced regulation capacity, high reactivity | Silbersweig et al., 2007 [24] |

| Impulsivity | OFC and DLPFC dysfunction | Poor inhibition and decision-making | Sebastian et al., 2014 [17] |

| Interpersonal Dysfunction | DMN alterations, Oxytocin signaling | Rejection sensitivity, unstable attachments | Preißler et al., 2010 [18] |

| Self-Harm | Opioid and dopamine system activation | Pain relief, compulsive repetition | Zhang et al., 2025 [25] |

| Domain | Neural Correlates | Key Studies |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional Dysregulation | Amygdala hyperactivity, Prefrontal cortex hypoactivity | [16,24] |

| 2. Impulsivity | Orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction, Dorsolateral PFC hypoactivity | [17,27] |

| 3. Interpersonal Dysfunction | Default Mode Network (DMN) alterations, Oxytocin dysregulation | [18,30] |

| 4. Self-Harm | HPA axis dysregulation, Endogenous opioid/dopamine system | [20,25] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannoulis, E.; Nousis, C.; Krokou, M.; Zikou, I.; Malogiannis, I. Wired for Intensity: The Neuropsychological Dynamics of Borderline Personality Disorders—An Integrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144973

Giannoulis E, Nousis C, Krokou M, Zikou I, Malogiannis I. Wired for Intensity: The Neuropsychological Dynamics of Borderline Personality Disorders—An Integrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(14):4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144973

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannoulis, Eleni, Christos Nousis, Maria Krokou, Ifigeneia Zikou, and Ioannis Malogiannis. 2025. "Wired for Intensity: The Neuropsychological Dynamics of Borderline Personality Disorders—An Integrative Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 14: 4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144973

APA StyleGiannoulis, E., Nousis, C., Krokou, M., Zikou, I., & Malogiannis, I. (2025). Wired for Intensity: The Neuropsychological Dynamics of Borderline Personality Disorders—An Integrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(14), 4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144973