Mesenteric Cysts as Rare Causes of Acute Abdominal Masses: Diagnostic Challenges and Surgical Insights from a Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General Classification: Benign vs. Malignant

1.2. Diagnostic Challenges in Emergency Settings

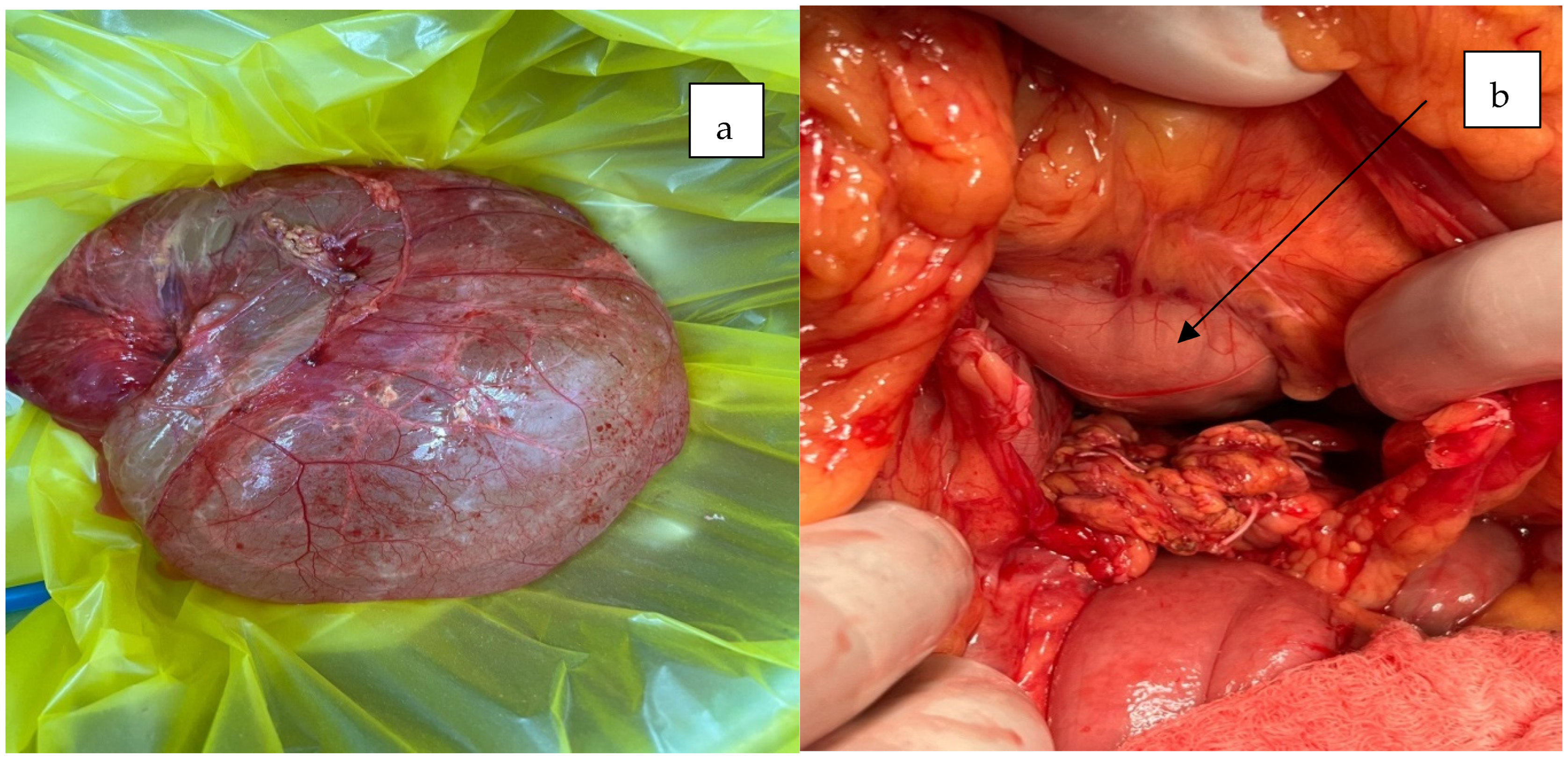

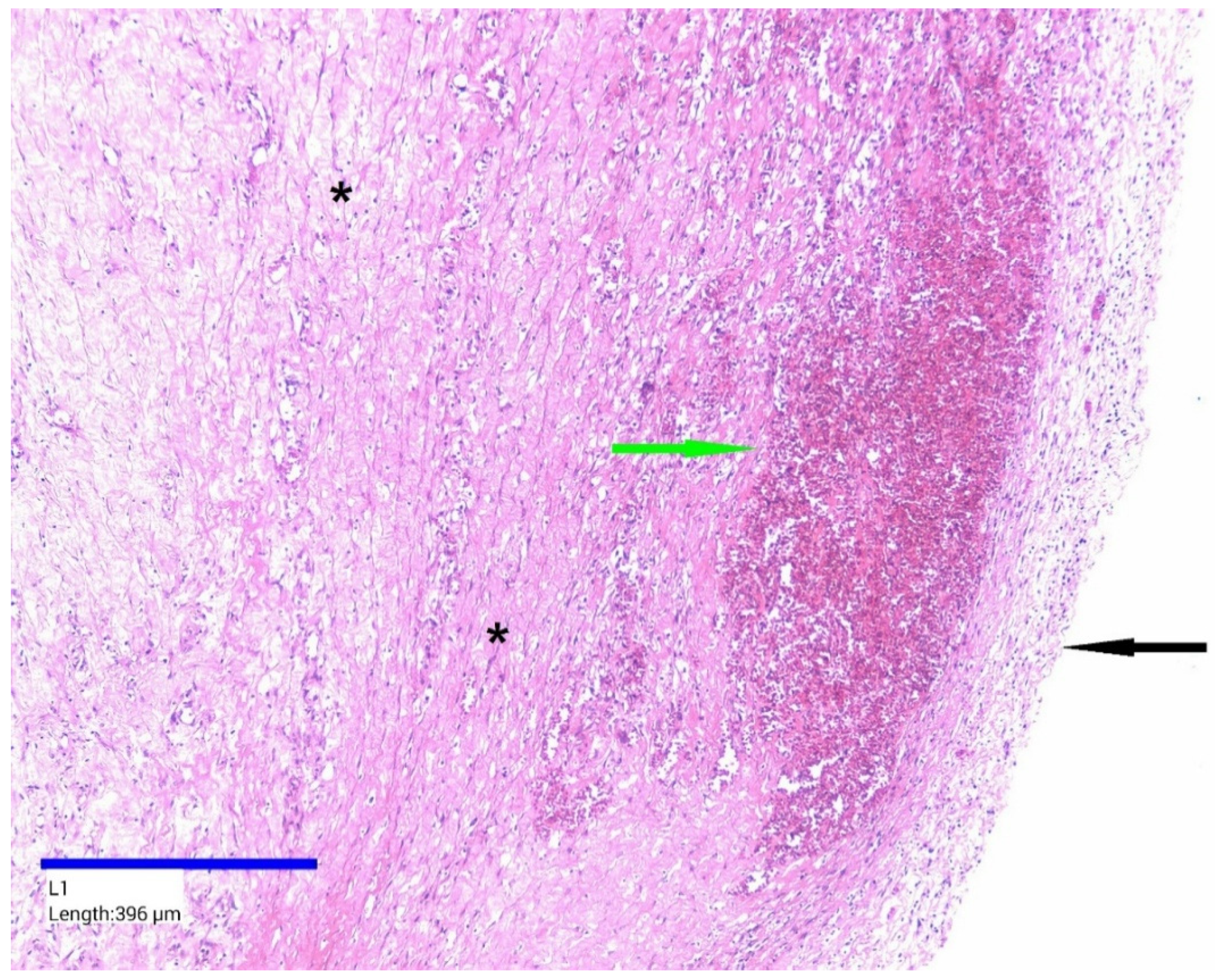

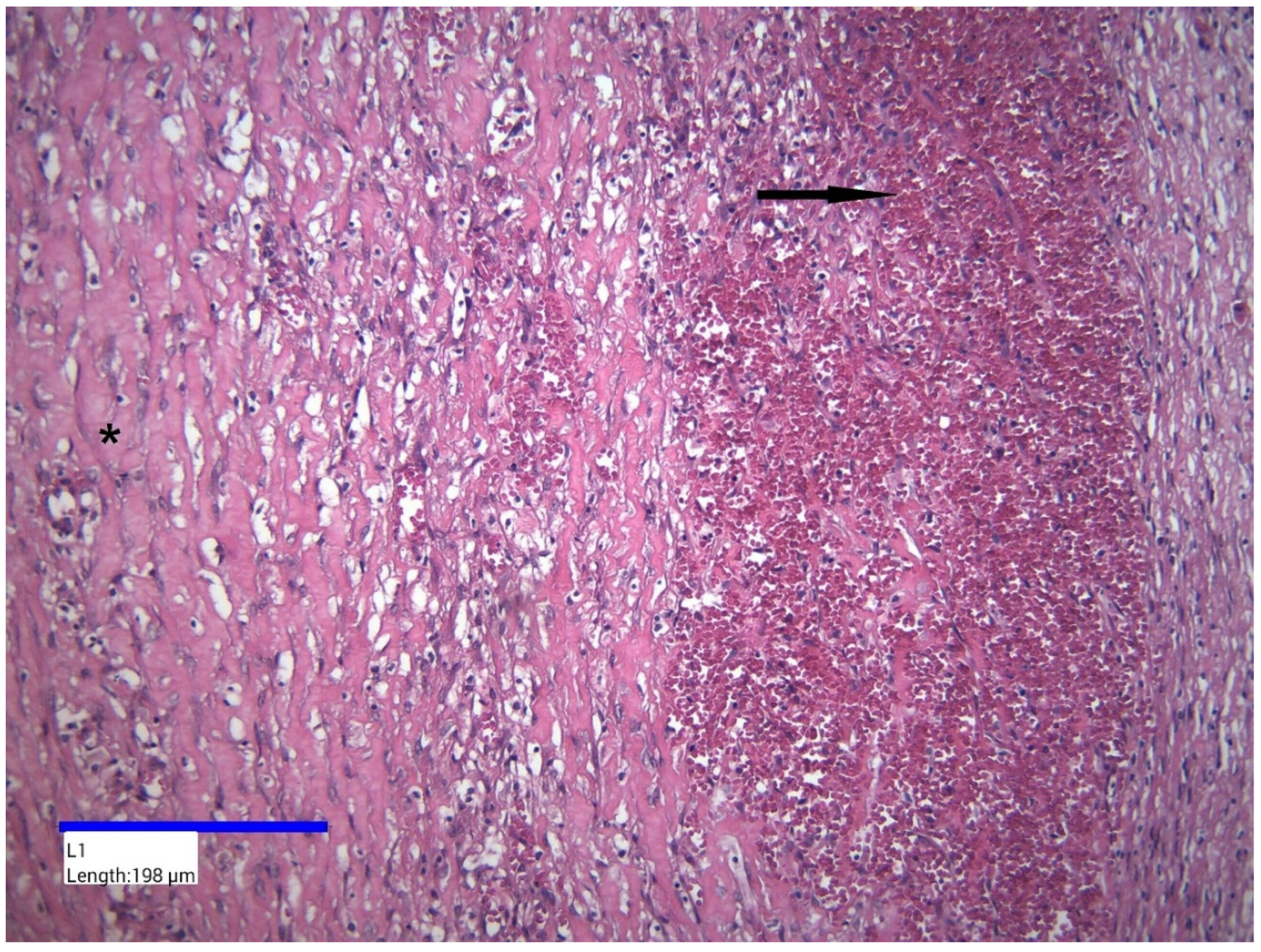

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

| Author (Ref) | Age at Diagnosis | Sex | Gastrointestinal Symptoms | Cystic Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolivar-Rodriguez [30] | 49 years | Male | Abdominal pain and abdominal distension | 13 × 10 cm |

| Ghritlaharey [31] | 8 years | Male | Pain, vomiting, abdominal distension | 10 × 8 cm |

| Park [32] | 72 years | Male | No symptoms | 13.5 × 9 cm |

| Pozzi [33] | 29 years | Male | Episodes of colicky abdominal pain and subjective discomfort | 8.5 × 7 cm |

| Mickovic [9] | 55 years | Male | Mild abdominal pain | 15 × 12 cm |

| Al Booq [34] | 42 years | Male | Abdominal pain | 14 × 10 cm |

| Pithawa [1] | 7 years | Male | Abdominal pain | 11 × 7 cm |

| Dioscoridi [35] | 61 years | Female | Asymptomatic | 10 cm |

| Li [36] | 25 years | Male | Abdominal pain and weight loss | 15 × 4 cm |

| Yoldemir [37] | 48 years | Female | Abdominal discomfort and nausea | 22 × 10 cm |

| Lee [38] | 34 years | Female | Abdominal discomfort and distension | 10 × 10 cm |

| Blanco [39] | 25 years | Male | Abdominal pain | 10 × 15 cm |

| Reddy [40] | 22 years | Female | Abdominal pain | 10 × 10 cm |

| Yagmur [41] | 20 years | Female | Distended abdomen | 33 × 14 cm |

| Karhan [42] | 5 years | Male | Abdominal distension | 25 × 20 cm |

| Rosado [43] | 55 years | Male | No symptoms | 15 × 10 cm |

3.1. Diagnostic Challenges

3.2. Intraoperative Challenges

3.3. Clinical and Surgical Lessons

- Differential Diagnosis and Use of Advanced Imaging

- 2.

- Assessment of Size and Impact on Adjacent Organs

- 3.

- Surgical Management

- 4.

- Postoperative Monitoring and Management of Complications

- 5.

- Importance of Early Diagnosis

Practical Recommendations for Future Similar Emergency Cases—Giant Mesenteric Cyst

- Maintain a High Index of Clinical Suspicion

- 2.

- Prompt and Comprehensive Imaging

- 3.

- Early Surgical Consultation

- 4.

- Careful Surgical Planning

- 5.

- Multidisciplinary Approach

- 6.

- Close Postoperative Monitoring and Follow-up

- 7.

- Case Documentation and Reporting

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pithawa, A.K.; Bansal, A.S.; Kochar, S.P. Mesenteric cyst: A rare intra-abdominal tumour. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2014, 70, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliaras, S.; Trygonis, S.; Papandoniou, A.; Kalamaras, S.; Trygonis, C.; Kiskinis, D. Mesenteric cyst of the descending colon: Report of a case. Acta Chir. Belg. 2006, 106, 714–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suldrup, F.; Uad, P.; Vaccaro, A.; Mazza, M.; Santino, J.; Mazza, O. Mesenteric root pseudocyst: Finding in an asymptomatic patient-a case report. Surg. Case Rep. 2024, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Bal, R.K.; Maudar, K.K. Mesenteric cyst—An unusual presentation. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1998, 33, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, S.C.; Glenn, D.C.; Storey, D.W. Mesenteric cyst. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1994, 64, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chaudhari, S.; Khattak, T.; Tiesenga, F. A Rare Case of Abdominal Tumor: Mesenteric Cyst. Cureus 2022, 14, e29949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, R.J.; Heimann, T.M.; Holt, J.; Beck, A.R. Mesenteric and retroperitoneal cysts. Ann. Surg. 1986, 203, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, K.; Pratap, A.; Naik, B.; Datta Sai Subramanyam, A.; Ansari, M.A. Intact Excision of a Mesenteric Pseudocyst. Cureus. 2023, 15, e40615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micković, S.; Bezmarević, M.; Nikolić-Micković, I.; Mitrović, M.; Tufegdzić, I.; Mirković, D.; Sekulović, L.; Trifunović, B. Traumatic mesenteric pseudocyst. Vojn. Pregl. 2014, 71, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milijkovic, D.; Gmijovic, D.; Radojkovic, M.; Gligorijevic, J.; Radovanovic, Z. Mesenteric cyst. Arch. Oncol. 2007, 15, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupati, R.K.; Krishnamurthy, P.; Rajamani, J.; Babuji, N.; Diriviraj, R.; Mohan, N.V.; Swamy, R.N.; Gurunathan, S.; Natarajan, M. Intraabdominal cystic swelling in children e laparoscopic approach, our experience. J. Indian. Paediatr. Surg. 2003, 8, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Agrawal, A.; Gupta, R.K.; Sanghvi, B.; Parelkar, S. Early management of mesenteric cyst prevents catastrophes: A single centre analysis of 17 cases. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2010, 7, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saviano, M.S.; Fundarò, S.; Gelmini, R.; Begossi, G.; Perrone, S.; Farinetti, A.; Criscuolo, M. Mesenteric cystic neoformations: Report of two cases. Surg. Today 1999, 29, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Agwany, A.M.S. Huge mesenteric cyst: Pelvic cysts differential diagnosis dilemma. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2016, 47, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crinò, S.F.; Bernardoni, L.; Manfrin, E.; Parisi, A.; Gabbrielli, A. Endoscopic ultrasound features of pancreatic schwannoma. Endosc. Ultrasound. 2016, 5, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, R.E. The Surgery of Infancy and Childhood: Its Principles and Techniques; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J.E.; Soper, N.J.; Brunt, L.M. Laparoscopic excision of mesenteric cysts: A report of two cases. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan Tech. 2001, 11, 382–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeda, V.B.; Booij, K.A.; Aronson, D.C. Mesenteric cystic lymphangioma: A congenital and an acquired anomaly? Two cases and a review of the literature. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2008, 43, 1206–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guraya, S.Y.; Salman, S.; Almaramhy, H.H. Giant mesenteric cyst. Clin. Pract. 2011, 1, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beahrs, O.H.; Judd, E.S., Jr.; Dockerty, M.B. Chylous cysts of the abdomen. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 1950, 30, 1081–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennemeyer, R.; Smith, M. Multicystic, peritoneal mesothelioma: A report with electron microscopy of a case mimicking intra-abdominal cystic hygroma (lymphangioma). Cancer 1979, 44, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, P.R.; Olmsted, W.W.; Moser, R.P., Jr.; Dachman, A.H.; Hjermstad, B.H.; Sobin, L.H. Mesenteric and omental cysts: Histologic classification with imaging correlation. Radiology 1987, 164, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falidas, E.; Mathioulakis, S.; Vlachos, K.; Pavlakis, E.; Anyfantakis, G.; Villias, C. Traumatic mesenteric cyst after blunt abdominal trauma. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2011, 2, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamiyeh, A.; Rieger, R.; Schrenk, P.; Wayand, W. Role of laparoscopic surgery in treatment of mesenteric cysts. Surg. Endosc. 1999, 13, 937–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzee, S.A.S.; Ali, M.M.M.; Mutisya, C.; Shaibu, Z.; Mutai, A.K.; Al-Busaidy, S.S.S.; Danbala, I.A. Mesenteric cyst manifested as partial intestinal obstruction. Clin. Med. Rev. Case Rep. 2024, 11, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, B.; Bagherian Lemraski, S.; Kouchak Hosseini, S.P.; Khoshnoudi, H.; Aghaei, M.; Haghbin Toutounchi, A. Small bowel volvulus and mesenteric ischemia induced by mesenteric cystic lymphangioma in an adult and literature review: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 105, 108083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbu, L.A.; Mărgăritescu, N.D.; Cercelaru, L.; Caragea, D.C.; Vîlcea, I.D.; Șurlin, V.; Mogoantă, S.Ș.; Mogoș, G.F.R.; Vasile, L.; Țenea Cojan, T.Ș. Can Thrombosed Abdominal Aortic Dissecting Aneurysm Cause Mesenteric Artery Thrombosis and Ischemic Colitis?-A Case Report and a Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.; Lasota, J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2006, 23, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, L.A.; Mărgăritescu, N.D.; Ghiluşi, M.C.; Belivacă, D.; Georgescu, E.F.; Ghelase, Ş.M.; Marinescu, D. Severe upper gastrointestinal bleeding from gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2016, 57, 1397–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar-Rodríguez, M.A.; Cazarez-Aguilar, M.A.; Luna-Madrid, E.E.; Morgan-Ortiz, F. Infected jejunal mesenteric pseudocyst: A case report. Cirugía Y Cirujanos 2015, 83, 334–338. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghritlaharey, R.K.; More, S. Chylolymphatic Cyst of Mesentery of Terminal Ileum: A Case Report in 8 Year-old Boy. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, ND05–ND07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.E.; Jeon, T.J.; Park, J.Y. Mesenteric pseudocyst of the transverse colon: Unusual presentation of more common pathology. BMJ Case Rep. 2014, bcr2013202682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, G.; Ferrarese, A.; Borello, A.; Catalano, S.; Surace, A.; Marola, S.; Gentile, V.; Martino, V.; Solej, M.; Nano, M. Percutaneous drainage and sclerosis of mesenteric cysts: Literature overview and report of an innovative approach. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12 (Suppl. S2), S90–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Booq, Y.; Hussain, S.S.; Elmy, M. Giant chylolymphatic mesenteric cyst and its successful enucleation: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014, 5, 469–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dioscoridi, L.; Perri, G.; Freschi, G. Chylous mesenteric cysts: A rare surgical challenge. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2014, 2014, rju012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Li, B.L.; Huang, X.; Zheng, C.J.; Zhou, J.L.; Zhao, Y.P. Ileal duplication mimicking intestinal intussusception: A congenital condition rarely reported in adult. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 6500–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoldemir, T.; Erenus, M. Fatty necrosis of a mesenteric cyst in a woman initially diagnosed with a large ovarian cystic mass. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 2013, 33, 534–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.L.; Madhuvrata, P.; Reed, M.W.; Balasubramanian, S.P. Chylous mesenteric cyst: A diagnostic dilemma. Asian J. Surg. 2016, 39, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, A.; Sonntag, C.; Giese, A. Right lower quadrant abdominal pain—The usual suspects? Diagnosis and therapy of a symptomatic mesenteric cyst. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2013, 138, 995–998. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, G.R.; Gunadal, S.; Banda, V.R.; Banda, N.R. Infected mesenteric cyst. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2012008195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagmur, Y.; Akbulut, S.; Gumus, S.; Babur, M.; Can, M.A. Case Report of Four Different Primary Mesenteric Neoplasms and Review of Literature. Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2016, 18, e28920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karhan, A.N.; Soyer, T.; Gunes, A.; Talim, B.; Karnak, I.; Oguz, B.; Saltik Temizel, I.N. Giant Omental Cyst (Lymphangioma) Mimicking Ascites and Tuberculosis. Iran. J. Radiol. 2016, 13, e31943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosado, C.R.B.; Machado, D.S.; de Magalhães Esteves, J.; Moreira, R.F.D.S.; de Castro Neves, C.M. A Case of Mesenteric Pseudocyst Causing Massive Abdominal Swelling. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2016, 3, 000364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbu, L.A.; Vasile, L.; Țenea-Cojan, T.Ș.; Mogoș, G.F.R.; Șurlin, V.; Vîlcea, I.D.; Cercelaru, L.; Mogoantă, S.Ș.; Mărgăritescu, N.D. Endometrioid adenofibroma of ovary—A literature review. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2025, 66, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samà, L.; Tzanis, D.; Bouhadiba, T.; Bonvalot, S. Emergency Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Surgery for Preoperative Rupture and Hemoperitoneum: A Case Report. Cureus 2021, 13, e13936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Perrot, M.; Bründler, M.A.; Tötsch, M.; Mentha, G.; Morel, P. Mesenteric cysts: Toward less confusion? A review. Surgery 2000, 127, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losanoff, J.E.; Kjossev, K.T.; El-Sherif, A.; Richman, B.W.; Weaver, D.W. Mesenteric cysts. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2003, 196, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Laboratory Results |

|---|---|

| White blood cell | 11 × 103 cells/µL |

| Hemoglobin | 13.2 g/dL |

| Platelet count | 200 × 103 cells/µL |

| Carbohydrate antigen 19.9 | 60.9 U/L |

| Carcioembryonic antigen | 1.39 ng/mL |

| Carbohydrate antigen 125 | 23.6 U/mL |

| ROMA score | 4.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbu, L.A.; Mărgăritescu, N.-D.; Cercelaru, L.; Vîlcea, I.-D.; Șurlin, V.; Mogoantă, S.-S.; Mogoș, G.F.R.; Țenea Cojan, T.S.; Vasile, L. Mesenteric Cysts as Rare Causes of Acute Abdominal Masses: Diagnostic Challenges and Surgical Insights from a Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144888

Barbu LA, Mărgăritescu N-D, Cercelaru L, Vîlcea I-D, Șurlin V, Mogoantă S-S, Mogoș GFR, Țenea Cojan TS, Vasile L. Mesenteric Cysts as Rare Causes of Acute Abdominal Masses: Diagnostic Challenges and Surgical Insights from a Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(14):4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144888

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbu, Laurențiu Augustus, Nicolae-Dragoș Mărgăritescu, Liliana Cercelaru, Ionică-Daniel Vîlcea, Valeriu Șurlin, Stelian-Stefaniță Mogoantă, Gabriel Florin Răzvan Mogoș, Tiberiu Stefăniță Țenea Cojan, and Liviu Vasile. 2025. "Mesenteric Cysts as Rare Causes of Acute Abdominal Masses: Diagnostic Challenges and Surgical Insights from a Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 14: 4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144888

APA StyleBarbu, L. A., Mărgăritescu, N.-D., Cercelaru, L., Vîlcea, I.-D., Șurlin, V., Mogoantă, S.-S., Mogoș, G. F. R., Țenea Cojan, T. S., & Vasile, L. (2025). Mesenteric Cysts as Rare Causes of Acute Abdominal Masses: Diagnostic Challenges and Surgical Insights from a Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(14), 4888. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14144888