Long-Term Results of Kidney Transplantation in Patients Aged 60 Years and Older

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To assess the survival of the recipients and transplanted kidneys, the function of the transplanted kidneys, and the frequency of complications;

- To analyze the factors influencing the survival of the recipients and transplanted kidneys in recipients aged 60 years and older compared to those recipients aged less than 60 years who received a kidney from the same deceased donor during long-term follow-up after transplantation.

2. Materials and Methods

- Survival of recipients and transplanted kidneys, including death-censored graft survival;

- The function of transplanted kidneys based on estimated glomerular filtration rate value (eGFR) calculated according to the MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) short formula;

- Occurrence of complications that may influence long-term results:

- (a)

- acute rejection episodes (AR), cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, post-transplant DM, and cancer;

- (b)

- CVDs and their complications, or the need for interventional management related to CAD: myocardial infarction (MI), percutaneous coronary angioplasty (PTCA), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), stroke, and transient ischemic attack (TIA).

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Central Statistical Office. Demographic Situation of Poland Until 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/population/population/demographic-situation-in-poland-up-to-2021-,13,2.html (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Central Statistical Office. Population Projection 2014–2050. Warszawa: Zakład Wydawnictw Statystycznych; 2014. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/population/population-projection/population-projection-2014-2050,2,5.html (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Central Statistical Office. Life Duration in 2021. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5470/2/16/1/trwanie_zycia_w_2021_roku.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Dębska-Ślizień, A.; Rutkowski, B.; Jagodziński, P.; Rutkowski, P.; Przygoda, J.; Lewandowska, D.; Czerwinski, J.; Kaminski, A.; Gellert, R. Current State of Renal Replacement Therapy in Poland in 2020. Available online: https://nefroldialpol.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/3.-NDP-1-2021-raport.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- ERA Registry Annual Report 2020. Available online: https://www.era-online.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/ERA-Registry-Annual-Report2020.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Awan, A.A.; Niu, J.; Pan, J.S.; Erickson, K.F.; Mandayam, S.; Winkelmayer, W.C.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Ramanathan, V. Trends in the Causes of Death among Kidney Transplant Recipients in the United States (1996–2014). Am. J. Nephrol. 2018, 48, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, M.; Auinger, M.; Anderwald, C.; Kästenbauer, T.; Kramar, R.; Feinböck, C.; Irsigler, K.; Kronenberg, F.; Prager, R. Long-term mortality and incidence of renal dialysis and transplantation in type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 3814–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Matheus, A.S.; Tannus, L.R.; Cobas, R.A.; Palma, C.C.; Negrato, C.A.; Gomes, M.B. Impact of diabetes on cardiovascular disease: An update. Int. J. Hypertens. 2013, 2013, 653789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerner, B.P.; Shivaswamy, V.; Desouza, C.V.; Larsen, J.L. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease following kidney transplantation. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2011, 7, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błędowski, P.; Grodzicki, T.; Mossakowska, M.; Zdrojewski, T. PROJEKT POLSENIOR 2—Study of individual areas of health status of the elderly, including health-related quality of life. Gdańsk 2021. Available online: https://polsenior2.gumed.edu.pl/attachment/attachment/82370/Polsenior_2.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Nikodimopoulou, M.; Karakasi, K.; Daoudaki, M.; Fouza, A.; Vagiotas, L.; Myserlis, G.; Antoniadis, N.; Salveridis, N.; Fouzas, I. Kidney Transplantation in Old Recipients From Old Donors: A Single-Center Experience. Transplant. Proc. 2019, 51, 405–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, M.; Bzoma, B.; Małyszko, J.; Małyszko, J.; Słupski, M.; Kobus, G.; Włodarczyk, Z.; Rutkowski, B.; Dębska-Ślizień, A. Early outcomes and long-term survival after kidney transplantation in elderly versus younger recipients from the same donor in a matched-pairs analysis. Medicine 2021, 23, 100, e28159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization and Coordination Center for Transplantation “POLTRANSPLANT”: Rules for Organ Distribution and Allocation. Available online: https://www.poltransplant.org.pl/alokacja2.html#nerki2016 (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Scherbov, S.; Sanderson, W. New Measures of Population Ageing. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/unpd_egm_201902_s1_sergeischerbov.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Older Persons. The UN Refugee Handbook. Available online: https://emergency.unhcr.org/protection/persons-risk/older-persons (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Neri, F.; Furian, L.; Cavallin, F.; Ravaioli, M.; Silvestre, C.; Donato, P.; La Manna, G.; Pinna, A.D.; Rigotti, P. How does age affect the outcome of kidney transplantation in elderly recipients? Clin. Transplant. 2017, 31, e13036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.J.; Yang, J.; Ahn, C.; Kim, M.S.; Han, D.J.; Kim, S.J.; Yang, C.W.; Chung, B.H.; Korean Organ Transplantation Registry Study Group. Clinical outcomes of kidney transplantation in older end-stage renal disease patients: A nationwide cohort study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Chen, G.; Qiu, J.; Wang, C.; Chen, L. Recipient-related risk factors for graft failure and death in elderly kidney transplant recipients. PLoS ONE 2014, 12, e112938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Raviña, F.; Rodríguez-Martínez, M.; Gude, F.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Valdés, F.; Sánchez-Guisande, D. Renal transplantation in the elderly: Does patient age determine the results? Age Ageing 2005, 34, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowska, D.; Czerwiński, J.; Hermanowicz, M.; Przygoda, J.; Podobińska, I.; Danielewicz, R. Organ Donation From Elderly Deceased Donors and Transplantation to Elderly Recipients in Poland: Numbers and Outcomes. Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 1390–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldal, K.; Leivestad, T.; Hartmann, A.; Svendsen, M.V.; Lien, B.H.; Midtvedt, K. Kidney transplantation in the elderly-the Norwegian experience. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adani, G.L.; Baccarani, U.; Crestale, S.; Pravisani, R.; Isola, M.; Tulissi, P.; Vallone, C.; Nappi, R.; Risaliti, A. Kidney Transplantation in Elderly Recipients: A Single-Center Experience. Transplant. Proc. 2019, 51, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, R.F.; Kennealey, P.T.; Elias, N.; Kawai, T.; Hertl, M.; Farrell, M.; Goes, N.; Hartono, C.; Tolkoff-Rubin, N.; Cosimi, A.B.; et al. Deceased donor kidney transplantation in elderly patients: Is there a difference in outcomes? Transplant. Proc. 2008, 40, 3413–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, H.M.; Dos Reis, M.A.; de Castro de Cintra Sesso, R.; Câmara, N.O.; Pacheco-Silva, A. Renal transplantation outcomes: A comparative analysis between elderly and younger recipients. Clin. Transplant. 2007, 21, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemini, R.; Rahamimov, R.; Ghinea, R.; Mor, E. Long-Term Results of Kidney Transplantation in the Elderly: Comparison between Different Donor Settings. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Avila, Y.; Patiño-Jaramillo, N.; Garcia Lopez, A.; Giron-Luque, F. Patient and Graft Survival in the Elderly Kidney Transplant Recipients. Rev. Colomb. Nefrol. 2021, 8, e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.; Farrugia, D.; Cheshire, J.; Mahboob, S.; Begaj, I.; Ray, D.; Sharif, A. Recipient age and risk for mortality after kidney transplantation in England. Transplantation 2014, 97, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.; Oz, N.; Fishman, G.; Shohat, T.; Rahamimov, R.; Mor, E.; Green, H.; Grossman, A. New onset diabetes after kidney transplantation is associated with increased mortality—A retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2017, 33, e2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullius, S.G.; Milford, E. Kidney allocation and the aging immune response. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1369–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandaswamy, R.; Humar, A.; Casingal, V.; Gillingham, K.J.; Ibrahim, H.; Matas, A.J. Stable kidney function in the second decade after kidney transplantation while on cyclosporine-based immunosuppression. Transplantation 2007, 83, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellemans, R.; Kramer, A.; De Meester, J.; Collart, F.; Kuypers, D.; Jadoul, M.; Van Laecke, S.; Le Moine, A.; Krzesinski, J.M.; Wissing, K.M.; et al. Does kidney transplantation with a standard or expanded criteria donor improve patient survival? Results from a Belgian cohort. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2021, 36, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schold, J.D.; Meier-Kriesche, H.U. Which renal transplant candidates should accept marginal kidneys in exchange for a shorter waiting time on dialysis? Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 1, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondos, A.; Döhler, B.; Brenner, H.; Opelz, G. Kidney graft survival in Europe and the United States: Strikingly different long-term outcomes. Transplantation 2013, 95, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kidney donor | n = 213 |

|---|---|

| Age [years] | 48.5 ± 11.1 |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 24.8 (23.1; 26.4) |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 [n (%)] | 16 (7.6) |

| Gender (female) [n (%)] | 80 (37.6) |

| Cardiovascular disease as a reason of death [n (%)] | 95 (44.6) |

| Arterial hypertension [n (%)] | 43 (20.2) |

| Serum creatinine [µmol/L] | 97.0 (73.0; 132.0) |

| eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [n (%)] | 43 (20.5) |

| Multiorgan donor [n (%)] | 44 (20.7) |

| Extended criteria donors [n (%)] | 138 (64.8) |

| Kidney Recipient | ≥60 Group | <60 Group | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recipients’ Clinical Parameters | |||

| Age [years] | 62.2 ± 3.5 | 44.2 ± 11.0 | – |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 25.8 ± 3.7 | 24.6 ± 3.6 | <0.01 |

| Gender (female) [n (%)] | 81 (38.03) | 85 (39.91) | 0.69 |

| Dialysis duration [months] | 35.0 (22.0; 51.0) | 30.5 (18.0; 53.0) | 0.26 |

| Patients with PRA > 25% [n (%)] | 27 (12.7) | 29 (13.6) | 0.77 |

| Re-transplantation [n (%)] | 14 (6.6) | 43 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| Pre-transplant DM [n (%)] | 44 (20.7) | 23 (10.8) | <0.01 |

| Arterial hypertension before KTx [n (%)] | 162 (76.1) | 162 (76.1) | 1.00 |

| CVD before KTx [n (%)] | 65 (30.5%) | 22 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| Transplantation procedure factors | |||

| Cold ischemia time [h] | 17.9 ± 7.0 | 18.8 ± 6.6 | 0.18 |

| HLA type I mismatch [points] | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 0.50 |

| HLA type II mismatch [points] | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.12 |

| Induction therapy [n (%)] | 104 (48.8) | 91 (42.7) | 0.21 |

| Induction therapy with Simulect [n (%)] | 57 (26.8) | 36 (16.9) | <0.05 |

| Induction therapy with ATG [n (%)] | 40 (18.8) | 51 (23.9) | |

| No induction therapy [n (%)] | 116 (54.4) | 126 (59.2) | |

| Cyclosporine A [n (%)] | 44 (20.7) | 48 (22.5) | 0.60 |

| Tacrolimus [n (%)] | 169 (79.3) | 163 (76.5) | |

| Lack of mentioned above [n (%)] | 0 | 2 (0.9) | – |

| Mofetetil or sodium mycofenolate [n (%)] | 199 (93.4) | 197 (92.5) | 0.92 |

| Azatiopryne [n (%)] | 11 (5.2) | 13 (6.1) | |

| mTOR inhibitor [n (%)] | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | |

| Double-J catheter implantation [n (%)] | 34 (16.0) | 27 (12.7) | 0.34 |

| Surgical complication * [n (%)] | 33 (15.49) | 31 (14.55) | 0.79 |

| Duration of hospitalization [days] | 19.1 ± 9.8 | 18.8 ± 10.4 | 0.43 |

| Recipients | ≥60 Group n = 213 | <60 Group n = 213 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

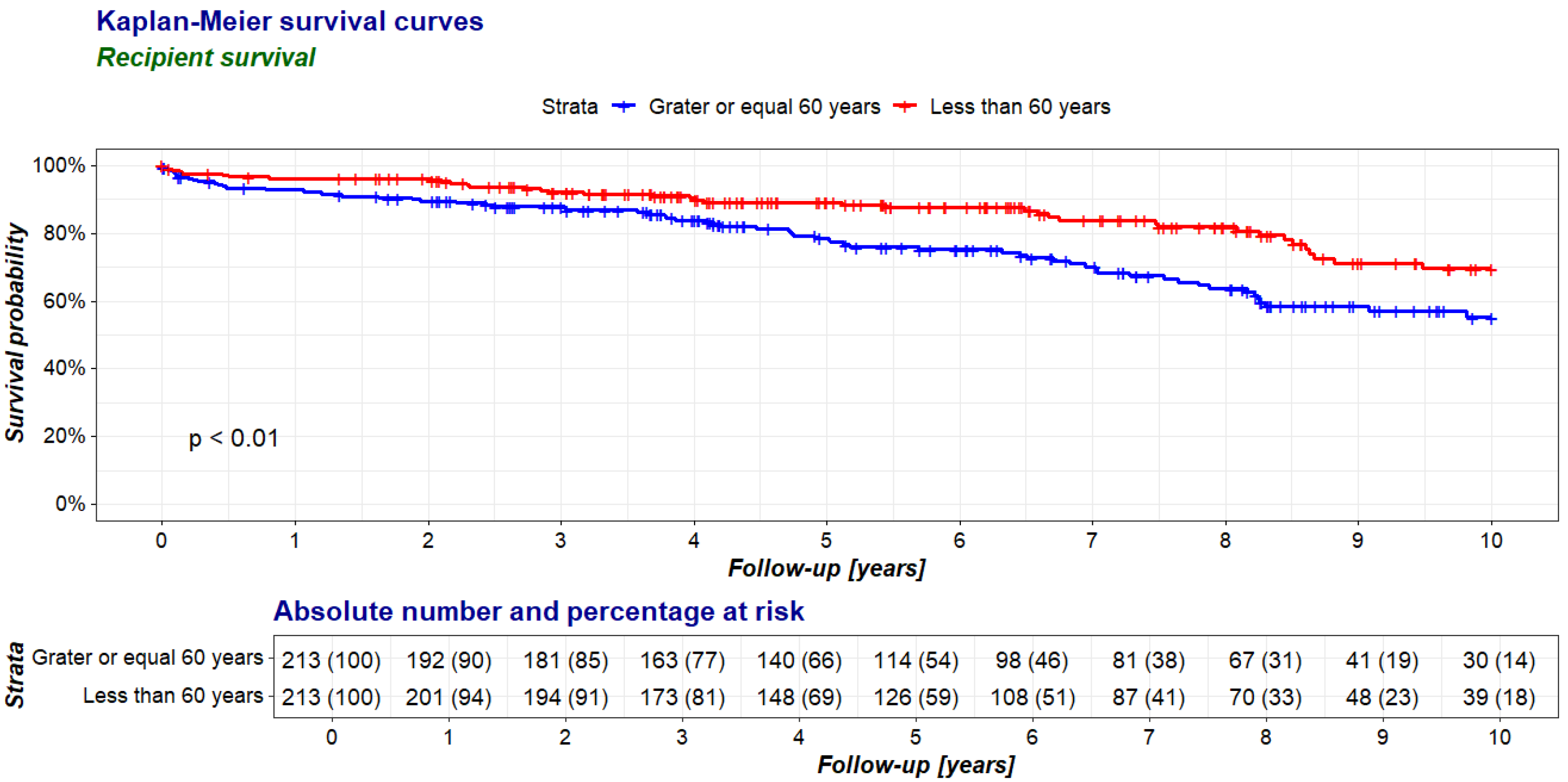

| 1 year | |||

| Recipient survival n(%) | 198 (93.0) | 205 (96.2) | 0.20 |

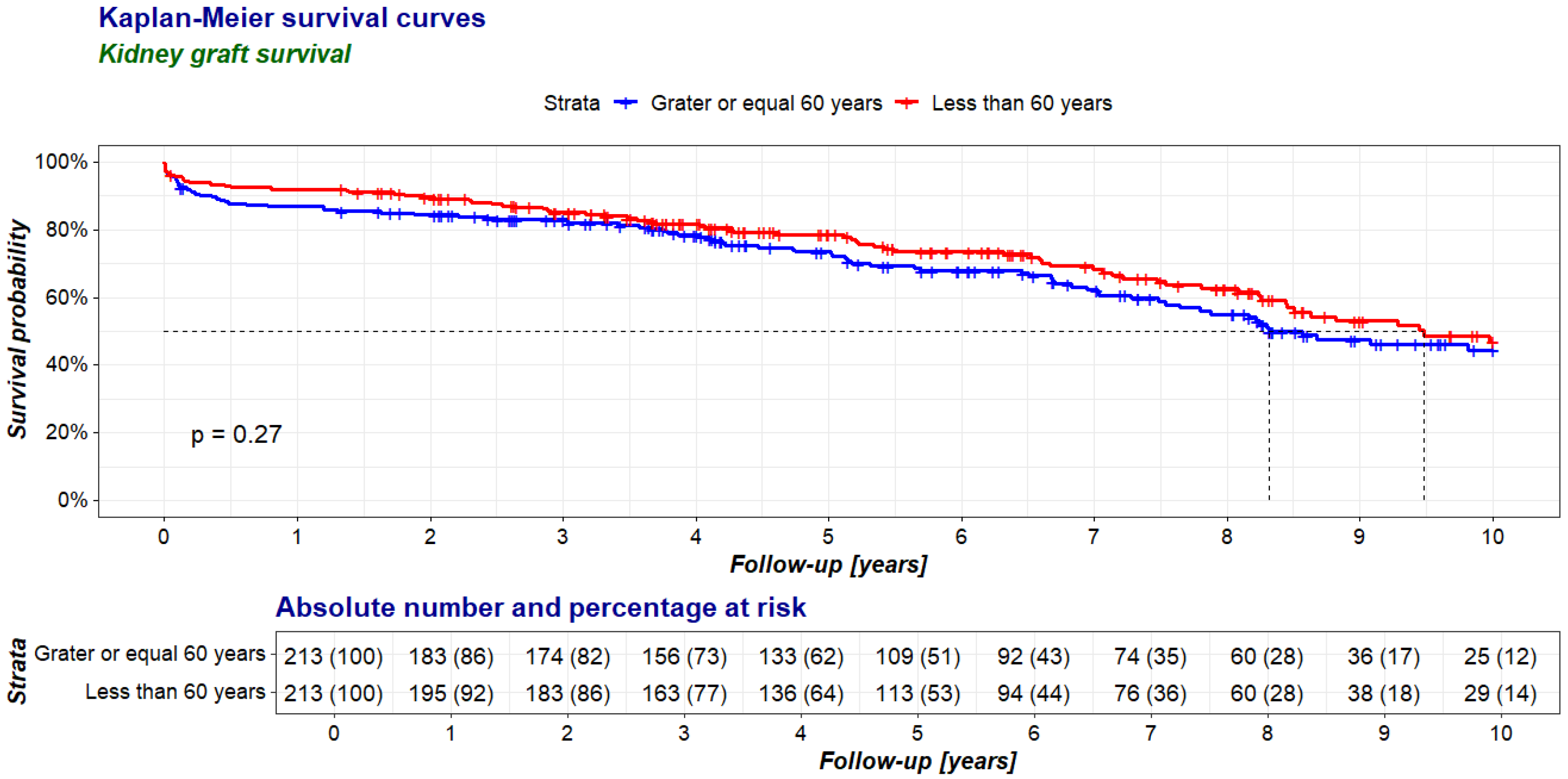

| Kidney graft survival n(%) | 185 (86.9) | 196 (92.0) | 0.11 |

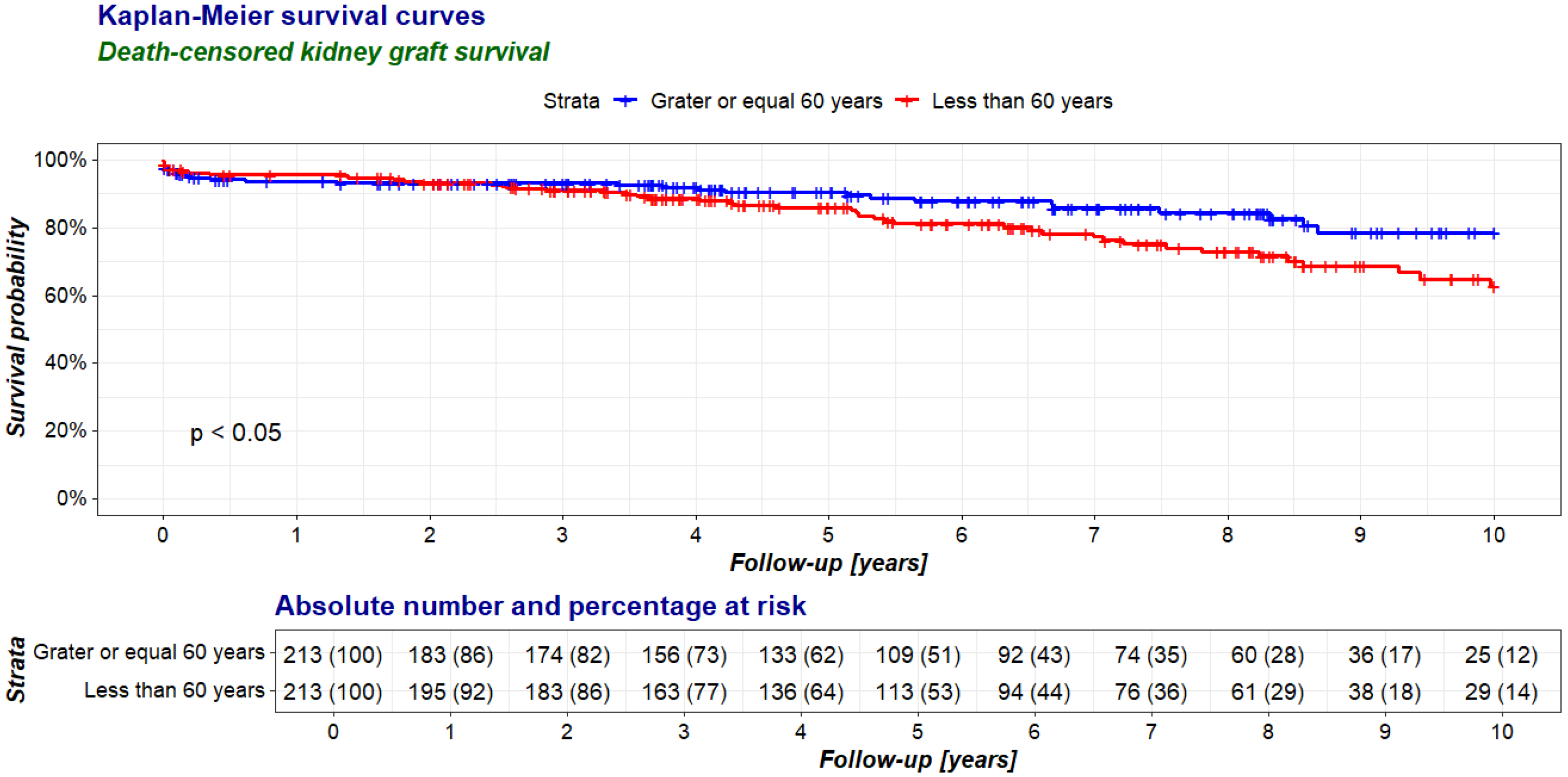

| Death-censored kidney graft survival % | 93.4 | 95.6 | 0.34 |

| 2 years | |||

| Recipient survival n(%) | 191 (89.7) | 205 (96.2) | <0.05 |

| Kidney graft survival n(%) | 180 (84.5) | 191 (89.7) | 0.15 |

| Death-censored kidney graft survival % | 94.2 | 93.2 | 0.66 |

| 5 years | |||

| Recipient survival n(%) | 173 (81.2) | 192 (90.1) | <0.05 |

| Kidney graft survival n(%) | 161 (75.6) | 171 (80.3) | 0.29 |

| Death-censored kidney graft survival % | 93.1 | 89.1 | 0.18 |

| 10 years | |||

| Recipient survival n(%) | 148 (69.5) | 175 (82.2) | <0.01 |

| Kidney graft survival n(%) | 129 (60.6) | 140 (65.7) | 0.31 |

| Death-censored kidney graft survival % | 87.2 | 80 | 0.09 |

| Recipients | ≥60 Group | <60 Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation Period | N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | p |

| 3 months | 171 | 53.8 | 18.3 | 178 | 56.7 | 20.7 | 0.18 |

| 1 year | 167 | 55.6 | 18.5 | 173 | 56.9 | 21.5 | 0.41 |

| 2 years | 162 | 54.3 | 19.1 | 169 | 55.0 | 21.3 | 0.73 |

| 3 years | 152 | 55.0 | 19.2 | 153 | 55.8 | 22.9 | 0.68 |

| 4 years | 126 | 55.6 | 19.9 | 127 | 54.3 | 21.2 | 0.46 |

| 5 years | 98 | 54.8 | 19.0 | 99 | 53.4 | 22.6 | 0.39 |

| 6 years | 84 | 56.3 | 18.3 | 84 | 50.9 | 21.0 | <0.05 |

| 7 years | 69 | 54.1 | 16.5 | 70 | 51.2 | 22.0 | 0.07 |

| 8 years | 52 | 50.4 | 18.5 | 58 | 53.3 | 22.8 | 0.96 |

| 9 years | 36 | 52.9 | 18.1 | 37 | 52.5 | 22.6 | <0.05 |

| 10 years | 23 | 48.9 | 17.0 | 28 | 47.6 | 21.1 | 0.12 |

| Recipients | ≥60 Group | <60 Group | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any acute rejection n (%) | 27 (12.7) | 35 (16.4) | 0.27 |

| Cytomegalovirus infection n (%) | 16 (7.5) | 16 (7.5) | 1.00 |

| Post-transplant diabetes n (%) | 42 (19.7) | 28 (13.2) | 0.07 |

| Any diabetes mellitus * n (%) | 86 (40.4) | 51 (23.9) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular diseases ** n (%) | 38 (17.8) | 20 (9.4) | <0.05 |

| Cancer n (%) | 30 (14.1) | 17 (8.0) | <0.05 |

| <60 Group | ≥60 Group | Stratified | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Dialysis duration (months) | 1.013 | 1.004, 1.022 | <0.01 | 1.022 | 1.012, 1.031 | <0.001 | 1.018 | 1.011, 1.024 | <0.001 |

| Extended criteria donors | X | 1.736 | 1.006, 2.996 | <0.05 | X | ||||

| Cold ischemia time (h) | X | 1.045 | 1.009, 1.082 | <0.05 | 1.033 | 1.004, 1.062 | <0.05 | ||

| Pre-transplant diabetes | X | X | 1.690 | 1.035, 2.762 | <0.05 | ||||

| CVD before KTx | X | X | 1.603 | 1.020, 2.520 | <0.05 | ||||

| <60 Group | ≥60 Group | Stratified | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Multiorgan donor | 0.551 | 0.346, 0.875 | <0.05 | X | 0.698 | 0.505, 0.965 | <0.05 | ||

| Any acute rejection | 2.671 | 1.600, 4.460 | <0.001 | X | 1.928 | 1.286, 2.891 | <0.001 | ||

| Surgical complication | 2.186 | 1.290, 3.705 | <0.01 | X | 1.662 | 1.134, 2.435 | 0.009 | ||

| Dialysis duration (mths) | 1.008 | 1.001, 1.015 | <0.05 | 1.021 | 1.013, 1.029 | <0.001 | 1.014 | 1.009, 1.019 | <0.001 |

| Extended criteria donor | X | 2.618 | 1.656, 4.141 | <0.001 | 2.061 | 1.447, 2.934 | <0.001 | ||

| Cold ischemia time (h) | X | 1.040 | 1.008, 1.074 | <0.05 | 1.029 | 1.004, 1.053 | <0.05 | ||

| Recipient gender (fem.) | X | X | 0.628 | 0.443, 0.891 | <0.01 | ||||

| Post-transplant diabetes | X | X | 0.564 | 0.358, 0.889 | <0.05 | ||||

| HLA type I mismatch | X | X | 1.188 | 1.022, 1.381 | <0.05 | ||||

| <60 Group | ≥60 Group | Stratified | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p |

| Multiorgan donor | 0.431 | 0.238, 0.781 | <0.01 | X | 0.469 | 0.294, 0.747 | <0.001 | ||

| Any acute rejection | 3.481 | 1.868, 6.488 | <0.001 | X | 2.385 | 1.411, 4.031 | <0.001 | ||

| Surgical complication | 2.320 | 1.176, 4.577 | <0.05 | 2.398 | 1.043, 5.512 | <0.05 | 2.452 | 1.463, 4.109 | <0.001 |

| Re-transplantation | 2.031 | 1.022, 4.033 | <0.05 | X | X | ||||

| Donor age | 1.050 | 1.015, 1.087 | <0.01 | X | X | ||||

| Extended criteria donor | X | 3.844 | 1.762, 8.385 | <0.001 | 2.512 | 1.552, 4.067 | <0.001 | ||

| Dialysis duration (mths) | X | 1.018 | 1.003, 1.032 | 0.017 | 1.010 | 1.002, 1.018 | <0.05 | ||

| HLA type I mismatch | X | X | 1.283 | 1.025, 1.608 | <0.05 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ziaja, J.; Skrabaka, D.; Owczarek, A.J.; Widera, M.; Król, R.; Kolonko, A.; Więcek, A. Long-Term Results of Kidney Transplantation in Patients Aged 60 Years and Older. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010078

Ziaja J, Skrabaka D, Owczarek AJ, Widera M, Król R, Kolonko A, Więcek A. Long-Term Results of Kidney Transplantation in Patients Aged 60 Years and Older. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleZiaja, Jacek, Damian Skrabaka, Aleksander J. Owczarek, Monika Widera, Robert Król, Aureliusz Kolonko, and Andrzej Więcek. 2025. "Long-Term Results of Kidney Transplantation in Patients Aged 60 Years and Older" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010078

APA StyleZiaja, J., Skrabaka, D., Owczarek, A. J., Widera, M., Król, R., Kolonko, A., & Więcek, A. (2025). Long-Term Results of Kidney Transplantation in Patients Aged 60 Years and Older. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14010078