Long-Term Follow-Up After Non-Curative Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastrointestinal Cancer—A Retrospective Multicenter Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

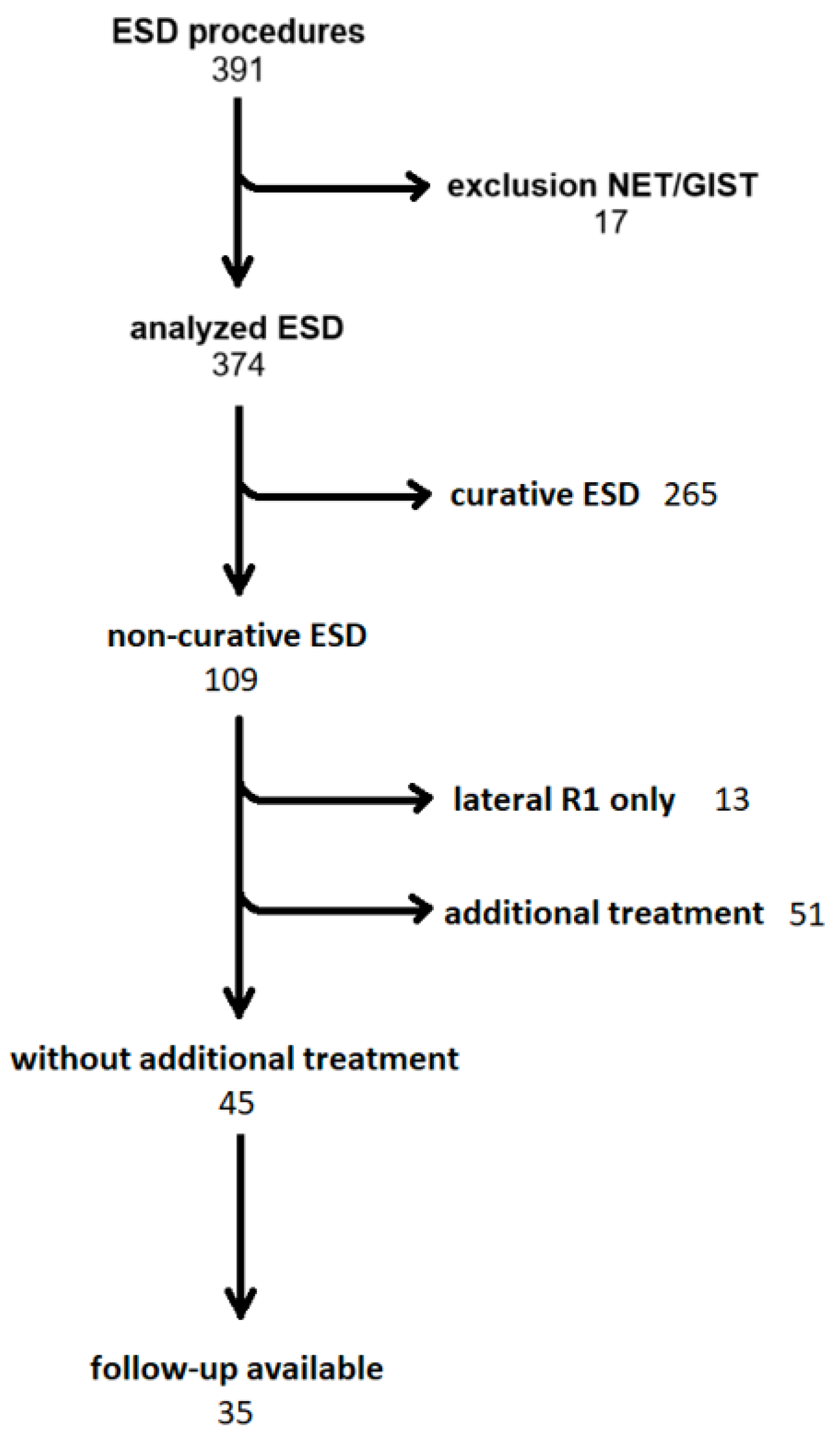

2. Methods

- -

- Squamous cell carcinoma in the esophagus: pT1b (sm1) (as expanded indication) with an invasion depth < 200 µm in the submucosal layer without risk factors (L0 and V0) and a tumor differentiation of G1 or G2.

- -

- Barrett´s carcinoma or carcinomas of the esophagogastric junction: pT1b (sm1) with an infiltration depth of up to 500 µm in the submucosal layer, L0, V0, and a tumor differentiation of G1 or G2.

- -

- Gastric carcinoma: A differentiated non-ulcerated tumor < 2 cm diameter and L0 and V0 with a maximum of one of the expanded criteria, namely pT1b (sm1) with an infiltration depth of up to 500 µm in the submucosal layer, a non-ulcerated lesion independent of size, a differentiated ulcerated lesion < 3 cm diameter, or an undifferentiated lesion < 2 cm in diameter.

- -

- Rectal cancer: Adenocarcinomas pT1b (sm1) with an infiltration depth of up to 1000 µm in the submucosal layer, L0, V0, a tumor differentiation of G1 or G2, and tumor budding ≤ 1.

Statistical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Comparison to Published Data

4.3. Individualized Multidisciplinary Approaches

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Uedo, N.; Iishi, H.; Tatsuta, M.; Ishihara, R.; Higashino, K.; Takeuchi, Y.; Imanaka, K.; Yamada, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Yamamoto, S.; et al. Longterm outcomes after endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2006, 9, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Hong, S.J.; Jang, J.Y.; Kim, S.E.; Seol, S.Y. Outcome after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer in Korea. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 3591–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, W.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Y.P.; Gao, J.; Wang, L.P.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.-X.; Chen, H.-Z.; Jin, H.; et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus esophagectomy for early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma with tumor invasion to different depths. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 2977–2992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marino, K.A.; Sullivan, J.L.; Weksler, B. Esophagectomy versus endoscopic resection for patients with early-stage esophageal adenocarcinoma: A National Cancer Database propensity-matched study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 155, 2211–2218.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, M.; Zhou, X.; Hu, M.; Pan, J. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for patients with early gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e025803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgourakis, G.; Gockel, I.; Lang, H. Endoscopic and surgical resection of T1a/T1b esophageal neoplasms: A systematic review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 1424–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, X.-B.; Li, S.-B.; Yang, Z.-H.; Tong, Q. Prediction of lymph node metastasis in superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis. Esophagus 2020, 33, doaa032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Hao, S.; Teng, H.; Guo, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Mao, T.; Li, Z. The possibility of endoscopic treatment of cN0 submucosal esophageal cancer: Results from a surgical cohort. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasawa, T.; Gotoda, T.; Miyata, S.; Kato, Y.; Shimoda, T.; Taniguchi, H.; Fujisaki, J.; Sano, T.; Yamaguchi, T. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2009, 12, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manner, H.; May, A.; Pech, O.; Gossner, L.; Rabenstein, T.; Günter, E.; Vieth, M.; Stolte, M.; Ell, C. Early Barrett’s carcinoma with “low-risk” submucosal invasion: Long-term results of endoscopic resection with a curative intent. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 2589–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoda, T.; Yanagisawa, A.; Sasako, M.; Ono, H.; Nakanishi, Y.; Shimoda, T.; Kato, Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: Estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer 2000, 3, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, L.A.; Pouw, R.E.; van Vilsteren, F.G.I.; Kate, F.J.W.T.; Visser, M.; Henegouwen, M.I.v.B.; Weusten, B.L.A.M.; Bergman, J.J.G.H.M. Risk of lymph node metastasis associated with deeper invasion by early adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and cardia: Study based on endoscopic resection specimens. Endoscopy 2010, 42, 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelfatah, M.M.; Barakat, M.; Othman, M.O.; Grimm, I.S.; Uedo, N. The incidence of lymph node metastasis in submucosal early gastric cancer according to the expanded criteria: A systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2019, 33, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.Y.; Jung, S.-A.; Shim, K.-N.; Cho, W.Y.; Keum, B.; Byeon, J.-S.; Huh, K.C.; Jang, B.I.; Chang, D.K.; Jung, H.-Y.; et al. Meta-analysis of predictive clinicopathologic factors for lymph node metastasis in patients with early colorectal carcinoma. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimingstorfer, P.; Biebl, M.; Gregus, M.; Kurz, F.; Schoefl, R.; Shamiyeh, A.; Spaun, G.O.; Ziachehabi, A.; Fuegger, R. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract and the Need for Rescue Surgery—A Multicenter Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; in Cho Cho, G.S.; Chung, J.C. Effect of non-curative endoscopic submucosal dissection on short-term outcomes of subsequent surgery for early gastric cancer. Asian J. Surg. 2022, 45, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, D.J.; Hendrix, J.M.; Garmon, E.H. American Society of Anesthesiologists Classification; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel-Nunes, P.; Libânio, D.; Bastiaansen, B.A.J.; Bhandari, P.; Bisschops, R.; Bourke, M.J.; Esposito, G.; Lemmers, A.; Maselli, R.; Messmann, H.; et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2022. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 591–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.G.; Cho, S.-J. Decision to perform additional surgery after non-curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer based on the risk of lymph node metastasis: A long-term follow-up study. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 7738–7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, C.; Probst, A.; Ebigbo, A.; Faiss, S.; Schumacher, B.; Allgaier, H.-P.; Dumoulin, F.; Steinbrueck, I.; Anzinger, M.; Marienhagen, J.; et al. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection in Europe: Results of 1000 Neoplastic Lesions from the German Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Registry. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganov, P.V.; Aihara, H.; Karasik, M.S.; Ngamruengphong, S.; Aadam, A.A.; Othman, M.O.; Sharma, N.; Grimm, I.S.; Rostom, A.; Elmunzer, B.J.; et al. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection in North America: A Large Prospective Multicenter Study. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2317–2327.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Antunes, J.; Marques, M.; Carneiro, F.; Macedo, G. Very low rate of residual neoplasia after non-curative endoscopic submucosal dissection: A western single-center experience. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadaccini, M.; Bourke, M.J.; Maselli, R.; Pioche, M.; Bhandari, P.; Jacques, J.; Haji, A.; Yang, D.; Albéniz, E.; Kaminski, M.F.; et al. Clinical outcome of non-curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early colorectal cancer. Gut 2022, 71, 1998–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, M.O.; Bahdi, F.; Ahmed, Y.; Gagneja, H.; Andrawes, S.; Groth, S.; Dhingra, S. Short-term clinical outcomes of non-curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early esophageal adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, e700–e708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Xu, W.; Qi, L.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, X.; Zhang, S. Clinical outcome of non-curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 15, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.Y.; Kim, G.H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.H.; Ryu, K.D.; Park, S.O.; Lee, B.E.; Song, G.A. Clinicopathologic factors predicting lymph node metastasis in superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 49, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönnow, C.-F.; Arthursson, V.; Toth, E.; Krarup, P.-M.; Syk, I.; Thorlacius, H. Lymphovascular Infiltration, Not Depth of Invasion, is the Critical Risk Factor of Metastases in Early Colorectal Cancer: Retrospective Population-based Cohort Study on Prospectively Collected Data, Including Validation. Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, e148–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, W.; Gotoda, T.; Oyama, T.; Kawata, N.; Takahashi, A.; Yoshifuku, Y.; Hoteya, S.; Nakagawa, M.; Hirano, M.; Esaki, M.; et al. A Scoring System to Stratify Curability after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer: “eCura system”. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, R.; Libanio, D.; Ribeiro, M.D.; Ferreira, A.; Barreiro, P.; Bourke, M.J.; Gupta, S.; Amaro, P.; Magalhães, R.K.; Cecinato, P.; et al. Predicting residual neoplasia after a non-curative gastric ESD: Validation and modification of the eCura system in the Western setting: The W-eCura score. Gut 2023, 73, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajiki, T.; Yamauchi, J.; Fujita, S.; Sato, M.; Miyazaki, K.; Ikeda, T.; Shirasaki, K.; Tsuchihara, K.; Kondo, N.; Ishiyama, S. Laparoscopic Lymphadenectomy without Gastrectomy for Lymph Nodes Recurrence after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD). Gan Kagaku Ryoho. Cancer Chemother. 2017, 44, 1223–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Minashi, K.; Nihei, K.; Mizusawa, J.; Takizawa, K.; Yano, T.; Ezoe, Y.; Tsuchida, T.; Ono, H.; Iizuka, T.; Hanaoka, N.; et al. Efficacy of Endoscopic Resection and Selective Chemoradiotherapy for Stage I Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 382–390.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, G.; Yamazaki, H.; Aibe, N.; Masui, K.; Sasaki, N.; Shimizu, D.; Kimoto, T.; Shiozaki, A.; Dohi, O.; Fujiwara, H.; et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection followed by chemoradiotherapy for superficial esophageal cancer: Choice of new approach. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 13, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, G.; Nishimura, M.; Hingorani, N.; Lin, I.-H.; Weiser, M.R.; Garcia-Aguilar, J.; Pappou, E.P.; Paty, P.B.; Schattner, M.A. Technical feasibility of salvage endoscopic submucosal dissection after chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2022, 96, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishizawa, T.; Ueda, T.; Ebinuma, H.; Toyoshima, O.; Suzuki, H. Long-Term Outcomes of Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Colorectal Epithelial Neoplasms: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2022, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoue, K.; Fukunaga, S.; Nagami, Y.; Sakai, T.; Maruyama, H.; Ominami, M.; Otani, K.; Hosomi, S.; Tanaka, F.; Taira, K.; et al. Long-term outcome of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer in patients with severe comorbidities: A comparative propensity score analysis. Gastric Cancer 2019, 22, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Esophagus | Stomach | Rectum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 16 | 10 | 9 |

| m | 9 | 4 | 0 |

| Sm1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Sm2 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Sm3 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| L | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| V | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Bd > 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| G1-2 | 8 | 6 | 8 |

| G3 | 8 | 4 | 1 |

| R1 horizontal | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| R1 vertical | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Organ | Histopathology | Recurrence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Esophagus | AC; pT1a (m1) Rx basal L0 V0 Pn0 G2 | Local |

| 2 | Esophagus | AC; pT1b (sm2) R1 basal L1 V0 Pn0 G3 | Local |

| 3 | Stomach | pT1b (sm2) R0 L1 V0 Pn0 G3 | Local |

| 4 | Esophagus | AC; pT1b (sm2) R1 basal L0 V0 Pn0 G2 | Local |

| 5 | Esophagus | AC pT1a (m1) G1 Rx basal L0 V0 Pn0 | Local |

| 6 | Esophagus | SCC pT1a (m3) L0 V0 Pn0 G3 R0 | Lymph node |

| 7 | Stomach | pT1b (sm3) L0 V0 Pn0 Rx G1 | local |

| ncESD | cESD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 35 | 33 | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 77 (11.3) | 72.9 (11.1) | 0.12 |

| Sex (% male) | 80 | 73 | 0.337 |

| ASA (mean) | 2.4 | 2.2 | 0.56 |

| Organ | |||

| Esophagus | 16 | 18 | |

| Stomach | 10 | 11 | |

| Rectum | 9 | 4 | |

| FU period (months, mean, SD) | 36.6 (27.1) | 16.2 (12.1) | 0.003 |

| Tumor recurrence | 7 (20%) | 1 (3%) | 0.017 |

| Local | 6 | 1 | |

| Lymph node | 1 | 0 | |

| Deaths | 3 | 1 | 0.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pimingstorfer, P.; Gregus, M.; Ziachehabi, A.; Függer, R.; Moschen, A.R.; Schöfl, R. Long-Term Follow-Up After Non-Curative Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastrointestinal Cancer—A Retrospective Multicenter Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6594. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216594

Pimingstorfer P, Gregus M, Ziachehabi A, Függer R, Moschen AR, Schöfl R. Long-Term Follow-Up After Non-Curative Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastrointestinal Cancer—A Retrospective Multicenter Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(21):6594. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216594

Chicago/Turabian StylePimingstorfer, Philipp, Matus Gregus, Alexander Ziachehabi, Reinhold Függer, Alexander R. Moschen, and Rainer Schöfl. 2024. "Long-Term Follow-Up After Non-Curative Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastrointestinal Cancer—A Retrospective Multicenter Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 21: 6594. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216594

APA StylePimingstorfer, P., Gregus, M., Ziachehabi, A., Függer, R., Moschen, A. R., & Schöfl, R. (2024). Long-Term Follow-Up After Non-Curative Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastrointestinal Cancer—A Retrospective Multicenter Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(21), 6594. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216594