Analysis of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Catalonia Based on SIDIAP

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study

2.2. Data Collection

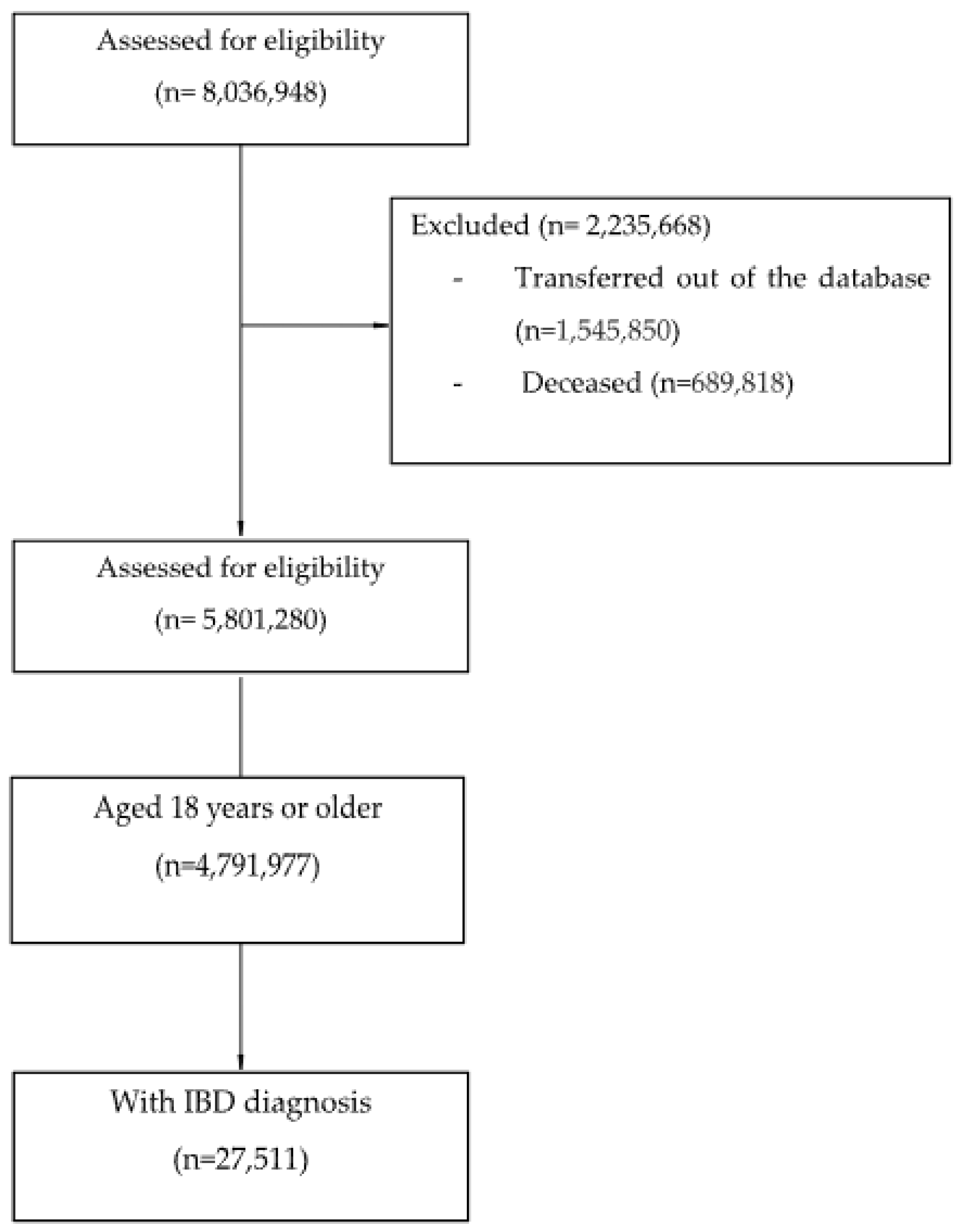

2.3. Population

- -

- Clinical diagnosis of IBD, including CD (International Classification of Diseases Version 10 (ICD-10: K50*)) and UC (ICD-10: K51*).

- -

- Age equal to or greater than 18 years old at the time of diagnosis.

- -

- People who had been transferred out of the database before 30 June 2021.

- -

- Deceased before 30 June 2021.

2.4. Sampling Procedure

2.5. Variables

2.6. Statistical Data Analysis

2.7. Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

4.2. Unhealthy Habits

4.3. Nutritional Status

4.4. Comorbidities

4.5. Anxiety and Depression

4.6. Treatment

4.7. Most Common Infections in IBD

4.8. Healthcare Management

4.9. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Monoclonal Antibodies |

| Rituximab |

| Ofatumumab |

| Brentuximab vedotin |

| Daratumumab |

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin |

| Immunosuppressants |

| Selective immunosuppressants |

| Mycophenolate mofetil |

| Sirolimus |

| Natalizumab |

| Abatacept |

| Eculizumab |

| Belimumab |

| Fingolimod |

| Teriflunomide |

| Apremilast |

| Alemtuzumab |

| Everolimus |

| Leflunomide |

| Vedolizumab |

| Belatacept |

| Ocrelizumab |

| Tofacitinib |

| Baricitinib |

| Muromonab-CD3 |

| Tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors (anti-TNF) |

| Etanercept |

| Infliximab |

| Adalimumab |

| Certolizumab pegol |

| Golimumab |

| Interleukin inhibitors |

| Basiliximab |

| Anakinra |

| Ustekinumab |

| Tocilizumab |

| Canakinumab |

| Ixekizumab |

| Secukinumab |

| Siltuximab |

| Calcineurin inhibitors |

| Ciclosporina |

| Tacrolimus |

| Other immunosuppressants |

| Azathioprine |

| Lenalidomide |

| Pirfenidone |

| Pomalidomide |

| Methotrexate |

| Thalidomide |

| Systemic glucocorticoids |

| Dexamethasone |

| Methylprednisolone |

| Prednisone |

| Deflazacort |

| Hydrocortisone |

| Prednisolone |

References

- Oltra, L.; Casellas, F. Enfermedad Inflamatoria Intestinal para Enfermería [Inflammatory Bowel Disease for Nursing]; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.geteii.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Monografiía-EII-enfermeriía.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Ginard, D.; Ricote, M.; Nos, P.; Pejenaute, M.E.; Sans, M.; Fontanillas, N.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Polo Garcia, J. Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians (SEMERGEN) and Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU) survey on the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 46, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, F.A.; Kane, S.V. Health Maintenance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2018, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, H.; Burisch, J.; Ellul, P.; Karmiris, K.; Katsanos, K.; Allocca, M.; Bamias, G.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Braithwaite, T.; Greuter, T.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Extraintestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2024, 18, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, K.; Dibley, L.; Chauhan, U.; Greveson, K.; Jäghult, S.; Ashton, K.; Buckton, S.; Duncan, J.; Hartmann, P.; Ipenburg, N.; et al. Second N-ECCO Consensus Statements on the European Nursing Roles in Caring for Patients with Crohn’s Disease or Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 12, 760–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.G. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaser, C.; Sturm, A.; Vavricka, S.R.; Kucharzik, T.; Fiorino, G.; Annese, V.; Calabrese, E.; Baumgart, D.C.; Bettenworth, D.; Nunes, P.B.; et al. ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.A.; Kennedy, N.A.; Raine, T.; Hendy, P.A.; Smith, P.J.; Limdi, J.K.; Bu’Hussain Hayee, B.H.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Parkes, G.C.; Selinger, C.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019, 68, s1–s106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Chan, F.K.L.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2020, 390, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D.; Parlett, L.E.; Jonsson, M.L.; Schaubel, D.E.; Hurtado-Lorenzo, A.; Kappelman, M.D. Incidence, Prevalence, and Racial and Ethnic Distribution of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 2023, 165, 1197–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coward, S.; Benchimol, E.I.; Kuenzig, M.E.; Windsor, J.W.; Bernstein, C.N.; Bitton, A.; Jones, J.L.; Lee, K.; Murthy, S.K.; Targownik, L.E.; et al. The 2023 Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada: Epidemiology of IBD, Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2023, 6, S9–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, L.; Ruiz de Morales, J.G.; Dauden, E.; Andreu, J.L.; Cervera, R.; Adán, A.; Marsal, S.; Escobar, C.; Hinojosa, J.; Palau, J.; et al. La prevalencia de diez enfermedades inflamatorias inmunomediadas (IMID) en España [Prevalence of ten immune-mediatedinflammatorydiseases (IMIDs) in Spain]. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2019, 93, e201903013. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/recursos_propios/resp/revista_cdrom/VOL93/ORIGINALES/RS93C_201903013.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Vegh, Z.; Burisch, J.; Pedersen, N.; Kaimakliotis, I.; Duricova, D.; Bortlik, M.; Avnstrøm, S.; Vinding, K.K.; Olsen, J.; Nielsen, K.R.; et al. Incidencia y evolución inicial de las enfermedades inflamatorias intestinales en 2011 en Europa y Australia: Resultados del inicio de ECCO-EpiCom en 2011 cohorte. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, M.; Garre, A.; Núñez Ortiz, A.; Diz-Lois Palomares, M.T.; Rodríguez, C.; Riestra, S.; Vela, M.; Benítez, J.M.; Fernández Salgado, E.; Sánchez Rodríguez, E.; et al. Incidence, Clinical Characteristics and Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Spain: Large-Scale Epidemiological Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recalde, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Burn, E.; Far, M.; García, D.; Carrere-Molina, J.; Benítez, M.; Moleras, A.; Pistillo, A.; Bolíbar, B.; et al. Data Resource Profile: The Information System for Research in Primary Care (SIDIAP). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 51, e324–e336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benchimol, E.I.; Kaplan, G.G.; Otley, A.R.; Nguyen, G.C.; Underwood, F.E.; Guttmann, A.; Jones, J.L.; Potter, B.K.; Catley, C.A.; Nugent, Z.J.; et al. Rural and Urban Residence During Early Life is Associated with Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Inception and Birth Cohort Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 1412–1422, Erratum in Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedamurthy, A.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Influence of Environmental Factors in the Development and Outcomes of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 15, 72–82. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6469265/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, I.S.; Molodecky, N.A.; Rabi, D.M.; Ghali, W.A.; Barkema, H.W.; Kaplan, G.G. The relationship between urban environment and the inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severs, M.; Van Erp, S.J.; Van der Valk, M.E.; Mangen, M.J.; Fidder, H.H.; van der Have, M.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; de Jong, D.J.; van der Woude, C.J.; Romberg-Camps, M.J.; et al. Smoking is Associated With Extra-intestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2016, 10, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashash, J.G.; Picco, M.F.; Farraye, F.A. Health Maintenance for Adult Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 2021, 19, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INE. Determinantes de Salud (Consumo de Tabaco, Exposición Pasiva al Humo de Tabaco, Alcohol, Problemas Medioambientales en la Vivienda). 2020. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ss/Satellite?param1=PYSDetalle&c=INESeccion_C¶m3=1259924822888&p=1254735110672&pagename=ProductosYServicios%2FPYSLayout&cid=1259926698156&L=1#:~:text=Seg%C3%BAn%20la%20Encuesta%20Europea%20de%20Salud%20en%20Espa%C3%B1a%202020%2C%20un,7%25%20en%20las%20mujeres (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Rozich, J.J.; Holmer, A.; Singh, S. Effect of Lifestyle Factors on Outcomes in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzouranis, G.; Fafliora, E.; Saridi, M.; Tatsioni, A.; Glanztounis, G.; Albani, E.; Katsanos, K.H.; Christodoulou, D.K. Alcohol and narcotics use in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2018, 31, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, N.; Castaño, D.; Patt, C.; Chu, T.; Cottrel, J.; Chang, S.L. Meta-analysis of alcohol induced gut dysbiosis and the resulting behavioral impact. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 376, 112196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrieri, P.; Ribolsi, M.; Guarino, M.P.L.; Emerenziani, S.; Altomare, A.; Cicala, M. Nutritional Aspects in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvano, M.; Capannolo, A.; Cesaro, N.; Stefanelli, G.; Fabiani, S.; Frassino, S.; Monaco, S.; Magistroni, M.; Viscido, A.; Latella, G. Nutrition, Nutritional Status, Micronutrients Deficiency, and Disease Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.L.; Rabinowitz, L.G.; Manning, L.; Keefer, L.; Rivera-Carrero, W.; Stanley, S.; Sherman, A.; Castillo, A.; Tse, S.; Hyne, A.; et al. High Prevalence of Malnutrition and Micronutrient Deficiencies in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Early in Disease Course. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2023, 29, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringle, P.L.; Stewart, K.O.; Peloquin, J.M.; Sturgeon, H.C.; Nguyen, D.; Sauk, J.; Garber, J.J.; Yajnik, V.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Chan, A.T.; et al. Body Mass Index, Genetic Susceptibility, and Risk of Complications Among Individuals with Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2304–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.; Burstein, E.; Cipher, D.J.; Linda, A. Feagins. Obesity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Marker of Less Severe Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 2436–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminerio, J.L.; Koutroubakis, I.E.; Ramos-Rivers, C.; Hashash, J.G.; Dudekula, A.; Regueiro, M.; Baidoo, L.; Barrie, A.; Swoger, J.; Schwartz, M.; et al. Impact of Obesity on the Management and Clinical Course of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2857–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, C.N.; Nugent, Z.; Shaffer, S.; Singh, H.; Marrie, R.A. Comorbidity before and after a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbord, M.; Annese, V.; Vavricka, S.R.; Allez, M.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Boberg, K.M.; Burisch, J.; De Vos, M.; De Vries, A.M.; Dick, A.D.; et al. The First European Evidence-based Consensus on Extra-intestinal Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2016, 10, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, T.H.; Allin, K.H.; Keefer, L.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Jess, T. Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: Epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 19, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, R.; Harding, A.; Stello, N.; Hanes, D.; Wahbeh, H. Depression and anxiety in patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 87, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashash, J.G.; Vachon, A.; Ramos Rivers, C.; Regueiro, M.D.; Binion, D.G.; Altman, L.; Williams, C.; Szigethy, E. Predictors of Suicidal Ideation Among IBD Outpatients. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 53, e41–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Rey, M.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Caamaño-Isorna, F.; Rodríguez, I.V.; Ferreiro, R.; Lindkvist, B.; González, A.L.; Dominguez-Munoz, J.E. Psychological Factors Are Associated with Changes in the Health-related Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, T.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Medical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.; Bonovas, S.; Doherty, G.; Kucharzik, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Raine, T.; Adamina, M.; Armuzzi, A.; Bachmann, O.; Bager, P.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2020, 14, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharzik, T.; Ellul, P.; Greuter, T.; Rahier, J.F.; Verstockt, B.; Abreu, C.; Albuquerque, A.; Allocca, M.; Esteve, M.; Farraye, F.A.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 879–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Facciorusso, A.; Dulai, P.S.; Jairath, V.; Sandborn, W.J. Comparative Risk of Serious Infections With Biologic and/or Immunosuppressive Therapy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabana, Y.; Rodríguez, L.; Lobatón, T.; Gordillo, T.; Montserrat, A.; Mena, R.; Beltrán, B.; Dotti, M.; Benitez, O.; Guardiola, J.; et al. Relevant Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and Their Relationship With Immunosuppressive Therapy and Their Effects on Disease Mortality. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinsley, A.; Navabi, S.; Williams, E.D.; Liu, G.; Kong, L.; Coates, M.D.; Clarke, K. Increased Risk of Influenza and Influenza-Related Complications Among 140,480 Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballos, C.A.M.; Gabbiadini, R.; Dal Buono, A.; Quadarella, A.; De Marco, A.; Repici, A.; Bezzio, C.; Simoneta, E.; Aliberti, S.; Armuzzi, A. Participación pulmonar en las enfermedades inflamatorias del intestino: Vías compartidas y conexiones no deseadas. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Vacunas y Programa de Vacunación. Herpes Zóster. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/vacunaciones/vacunas/ciudadanos/zoster.htm (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- García-Serrano, C.; Artigues-Barberà, E.; Mirada, G.; Estany, P.; Sol, J.; Ortega Bravo, M. Impact of an Intervention to Promote the Vaccination of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Serrano, C.; Mirada, G.; Marsal, J.R.; Ortega, M.; Sol, J.; Solano, R.; Artigues, E.M.; Estany, P. Compliance with the guidelines on recommended immunization schedule in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Implications on public health policies. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Carlson, S.A.; Greenlund, K.J. Understanding primary care providers’ attitudes towards preventive screenings to patients with inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farraye, F.A.; Melmed, G.Y.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Kane, S.V. ACG Clinical Guideline: Preventive Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 112, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, G.; Lytras, T.; Younge, L.; Fidalgo, C.; Coenen, S.; Chaparro, M.; Allocca, M.; Arnott, I.; Bossuyt, P.; Burisch, J.; et al. Quality of Care Standards in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] Position Paper. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2020, 14, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 27,511) | Ulcerative Colitis (n = 18,064) | Crohn’s Disease (n = 9477) | p-Value | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Women | 13,628 (49.50%) | 8772 (48.60%) | 4856 (51.40%) | |

| Men | 13,883 (50.50%) | 9292 (51.40%) | 4591 (48.60%) | |

| Age of diagnosis | 42.9 (16.3) | 45.3 (16.0) | 38.4 (15.9) | <0.001 |

| Age at June 2021 | 54.3 (16.7) | 56.8 (16.5) | 49.4 (16.0) | <0.001 |

| Residence area | <0.001 | |||

| Rural area | 1519 (5.94%) | 1066 (6.33%) | 453 (5.18%) | |

| Urban area | 24,073 (94.10%) | 15,778 (93.70%) | 8295 (94.80%) | |

| Unhealthy habits | ||||

| Tobacco consumption | <0.001 | |||

| Non-smoker | 11,919 (46.40%) | 8383 (49.60%) | 3536 (40.20%) | |

| Smoker | 5448 (21.20%) | 2707 (16.00%) | 2741 (31.20%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 8327 (32.40%) | 5817 (34.40%) | 2510 (28.60%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | <0.001 | |||

| Non-drinker | 14,995 (60.40%) | 9705 (59.30%) | 5290 (62.60%) | |

| Low risk consumption | 9575 (38.60%) | 6499 (39.70%) | 3076 (36.40%) | |

| Heavy drinker | 249 (1.00%) | 169 (1.03%) | 80 (0.95%) | |

| All (n = 27,511) | Ulcerative Colitis (n = 18,064) | Crohn’s Disease (n = 9477) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (numeric) | 26.2 (5.04) | 26.5 (4.89) | 25.7 (5.28) | <0.001 |

| BMI (categorical) | <0.001 | |||

| Underweight | 711 (2.99%) | 329 (2.11%) | 382 (4.69%) | |

| Normal weight | 9715 (40.90%) | 6071 (38.90%) | 3644 (44.80%) | |

| Obesity | 4440 (18.70%) | 3048 (19.50%) | 1392 (17.10%) | |

| Morbid obesity | 306 (1.29%) | 198 (1.27%) | 108 (1.33%) | |

| Overweight | 8592 (36.20%) | 5976 (38.30%) | 2616 (32.10%) | |

| Malnutrition | 74 (0.27%) | 32 (0.18%) | 42 (0.44%) | <0.001 |

| Prognostic Comorbidity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 27,511) | Ulcerative Colitis (n = 18,064) | Crohn’s Disease (n = 9477) | p-Value | |

| Charlson index (numeric) | 0.76 (1.23) | 0.82 (1.29) | 0.65 (1.11) | <0.001 |

| Charlson index (categorical) | <0.001 | |||

| High comorbidity | 2268 (8.24%) | 1701 (9.42%) | 567 (6.00%) | |

| Absence of comorbidity | 15,967 (58.00%) | 10,182 (56.40%) | 5785 (61.20%) | |

| Low comorbidity | 9276 (33.70%) | 6181 (34.20%) | 3095 (32.80%) | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | ||||

| Dyslipidaemia | 3401 (11,054 pcm) | 2552 (14,128 pcm) | 849 (8959 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension | 7246 (26,339 pcm) | 5245 (29,036 pcm) | 2001 (21,114 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 533 (1937 pcm) | 398 (2203 pcm) | 135 (1425 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Endocrinological diseases | ||||

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2827 (10,276 pcm) | 2111 (11,686 pcm) | 716 (7555 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory diseases | ||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1143 (4155 pcm) | 816 (4517 pcm) | 327 (3450 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders | ||||

| Anxiety | 10,050 (36,531 pcm) | 6353 (35,169 pcm) | 3697 (39,010 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 4032 (14,656 pcm) | 2629 (14,554 pcm) | 1403 (14,804 pcm) | 0.519 |

| Cervical dysplasia/neoplasms | ||||

| Cervical dysplasia | 423 (3104 pcm) | 206 (2348 pcm) | 217 (4469 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Neoplasms | 166 (603 pcm) | 98 (543 pcm) | 68 (718 pcm) | 0.085 |

| Other diseases | ||||

| Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases | 2753 (10,007) | 1601 (8863 pcm) | 1152 (12,156 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure | 1558 (5663 pcm) | 1146 (6344 pcm) | 412 (4347 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Referrals and Total Visits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 27,511) | Ulcerative Colitis (n = 18,064) | Crohn’s Disease (n = 9477) | p-Value | |

| Any referral to gastroenterology | 6849 (24.90%) | 4720 (26.10%) | 2129 (22.50%) | <0.001 |

| Number of referrals to gastroenterology (in referred patients) | 1.45 (0.84) | 1.46 (0.85) | 1.42 (0.82) | 0.026 |

| Any referral to general surgery | 3267 (11.90%) | 2175 (12.00%) | 1092 (11.60%) | 0.249 |

| Number of referrals to general surgery (in referred patients) | 1.31 (0.67) | 1.31 (0.66) | 1.32 (0.67) | 0.808 |

| Any referral to psychiatry/psychology | 2744 (9.97%) | 1594 (8.82%) | 1150 (12.20%) | <0.001 |

| Number of referrals to psychiatry/psychology (in referred patients) | 1.50 (0.92) | 1.48 (0.88) | 1.54 (0.97) | 0.098 |

| Any referral to rheumatology | 2448 (8.90%) | 1629 (9.02%) | 819 (8.67%) | 0.346 |

| Number of referrals to rheumatology (in referred patients) | 1.38 (0.79) | 1.39 (0.81) | 1.35 (0.75) | 0.227 |

| Any referral to endocrinology | 976 (3.55%) | 638 (3.53%) | 338 (3.58%) | 0.872 |

| Number of referrals to endocrinology (in referred patients) | 1.27 (0.62) | 1.29 (0.62) | 1.24 (0.62) | 0.243 |

| Any referral to digestive surgery | 346 (1.26%) | 247 (1.37%) | 99 (1.05%) | 0.028 |

| Number of referrals to digestive surgery (in referred patients) | 1.08 (0.30) | 1.09 (0.31) | 1.05 (0.26) | 0.294 |

| Any visit by general practitioners | 27,106 (98.50%) | 17,800 (98.50%) | 9306 (98.50%) | 0.88 |

| Number of visits by general practitioners (in patients visited) | 53.3 (49.3) | 54.5 (50.6) | 51.1 (46.6) | <0.001 |

| Any visit by nurses | 25,897 (94.10%) | 16,939 (93.80%) | 8958 (94.80%) | <0.001 |

| Number of visits per nurse (in patients visited) | 28.5 (42.8) | 27.8 (41.5) | 29.8 (45.2) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalisations | ||||

| Due to IBD | ||||

| Any visit to the emergency department | 10,806 (39.30%) | 5681 (31.40%) | 5125 (54.30%) | <0.001 |

| Number of emergency department visits (in visited patients) | 2.79 (2.79) | 2.35 (2.35) | 3.28 (3.14) | <0.001 |

| Any hospitalisation | 9018 (32.80%) | 4570 (25.30%) | 4448 (47.10%) | <0.001 |

| Number of hospitalisations (in hospitalised patients) | 2.33 (2.15) | 2.03 (1.83) | 2.63 (2.39) | <0.001 |

| Any admission to Intensive Care Unit | 142 (0.52%) | 63 (0.35%) | 79 (0.84%) | <0.001 |

| Number of admissions to Intensive Care Unit (in admitted patients) | 1.20 (0.50) | 1.21 (0.60) | 1.20 (0.40) | 0.966 |

| Due to infection | ||||

| Any visit to the emergency department | 1330 (4.83%) | 830 (4.59%) | 500 (5.29%) | 0.011 |

| Number of emergency department visits (in visited patients) | 1.38 (0.94) | 1.37 (0.96) | 1.38 (0.89) | 0.834 |

| Any hospitalisation | 1255 (4.56%) | 781 (4.32%) | 474 (5.02%) | 0.01 |

| Number of hospitalisations (in hospitalised patients) | 1.36 (0.93) | 1.36 (0.95) | 1.37 (0.90) | 0.804 |

| Any admission to Intensive Care Unit | 27 (0.10%) | 15 (0.08%) | 12 (0.13%) | 0.366 |

| Number of admissions to Intensive Care Unit (in admitted patients) | 1.48 (0.85) | 1.27 (0.46) | 1.75 (1.14) | 0.188 |

| All (n = 27,511) | Ulcerative Colitis (n = 18,064) | Crohn’s Disease (n = 9477) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids | 1525 (5.54%) | 1002 (5.55%) | 523 (5.54%) | 0.992 |

| Selective immunosuppressants | 47 (0.17%) | 36 (0.20%) | 11 (0.12%) | 0.154 |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | 206 (0.75%) | 139 (0.77%) | 67 (0.71%) | 0.633 |

| Other immunosuppressants | 4565 (16.60%) | 1679 (9.29%) | 2886 (30.50%) | <0.001 |

| Total prescribed drugs: | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 21,697 (78.90%) | 15,491 (85.8%) | 6206 (65.70%) | |

| 1 | 5310 (19.30%) | 2307 (12.80%) | 3003 (31.80%) | |

| 2 | 478 (1.74%) | 249 (1.38%) | 229 (2.42%) | |

| 3 | 26 (0.09%) | 17 (0.09%) | 9 (0.10%) | |

| Multiple drugs | 504 (1.83%) | 266 (1.47%) | 238 (2.52%) | <0.001 |

| All (n = 27,511) | Ulcerative Colitis (n = 18,064) | Crohn’s Disease (n = 9477) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other infectious diseases | 273 (992 pcm) | 151 (836 pcm) | 122 (1287 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Influenza | 5325 (19,356 pcm) | 3400 (18,822 pcm) | 1925 (20,312 pcm) | 0.002 |

| Hepatitis A | 80 (291 pcm) | 56 (310 pcm) | 24 (253 pcm) | 0.484 |

| Hepatitis B | 219 (796 pcm) | 157 (869 pcm) | 62 (654 pcm) | 0.07 |

| Hepatitis C | 274 (996 pcm) | 184 (1019 pcm) | 90 (950 pcm) | 0.646 |

| Unspecified hepatitis | 101 (367 pcm) | 61 (338 pcm) | 40 (422 pcm) | 0.312 |

| Herpes zoster | 2228 (8099 pcm) | 1436 (7950 pcm) | 792 (8357 pcm) | 0.219 |

| Mumps | 74 (269 pcm) | 47 (260 pcm) | 27 (285 pcm) | 0.789 |

| Rubella | 36 (131 pcm) | 22 (122 pcm) | 14 (148 pcm) | 0.689 |

| Tetanus | 0 (0 pcm) | 0 (0 pcm) | 0 (0 pcm) | - |

| Chickenpox | 1911 (6946 pcm) | 972 (5381 pcm) | 939 (9908 pcm) | <0.001 |

| Measles | 120 (436 pcm) | 69 (382 pcm) | 51 (538 pcm) | 0.073 |

| Human papillomavirus | 196 (712 pcm) | 109 (603 pcm) | 87 (918 pcm) | 0.004 |

| Pneumonia | 2140 (7779 pcm) | 1455 (8054 pcm) | 685 (7228 pcm) | 0.019 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Serrano, C.; Mirada, G.; Estany, P.; Sol, J.; Ortega-Bravo, M.; Artigues-Barberà, E. Analysis of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Catalonia Based on SIDIAP. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216476

García-Serrano C, Mirada G, Estany P, Sol J, Ortega-Bravo M, Artigues-Barberà E. Analysis of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Catalonia Based on SIDIAP. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(21):6476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216476

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Serrano, Cristina, Gloria Mirada, Pepi Estany, Joaquim Sol, Marta Ortega-Bravo, and Eva Artigues-Barberà. 2024. "Analysis of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Catalonia Based on SIDIAP" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 21: 6476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216476

APA StyleGarcía-Serrano, C., Mirada, G., Estany, P., Sol, J., Ortega-Bravo, M., & Artigues-Barberà, E. (2024). Analysis of Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Catalonia Based on SIDIAP. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(21), 6476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216476