Beyond Boundaries of a Trial: Post-Market Clinical Follow-Up of SOYA Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

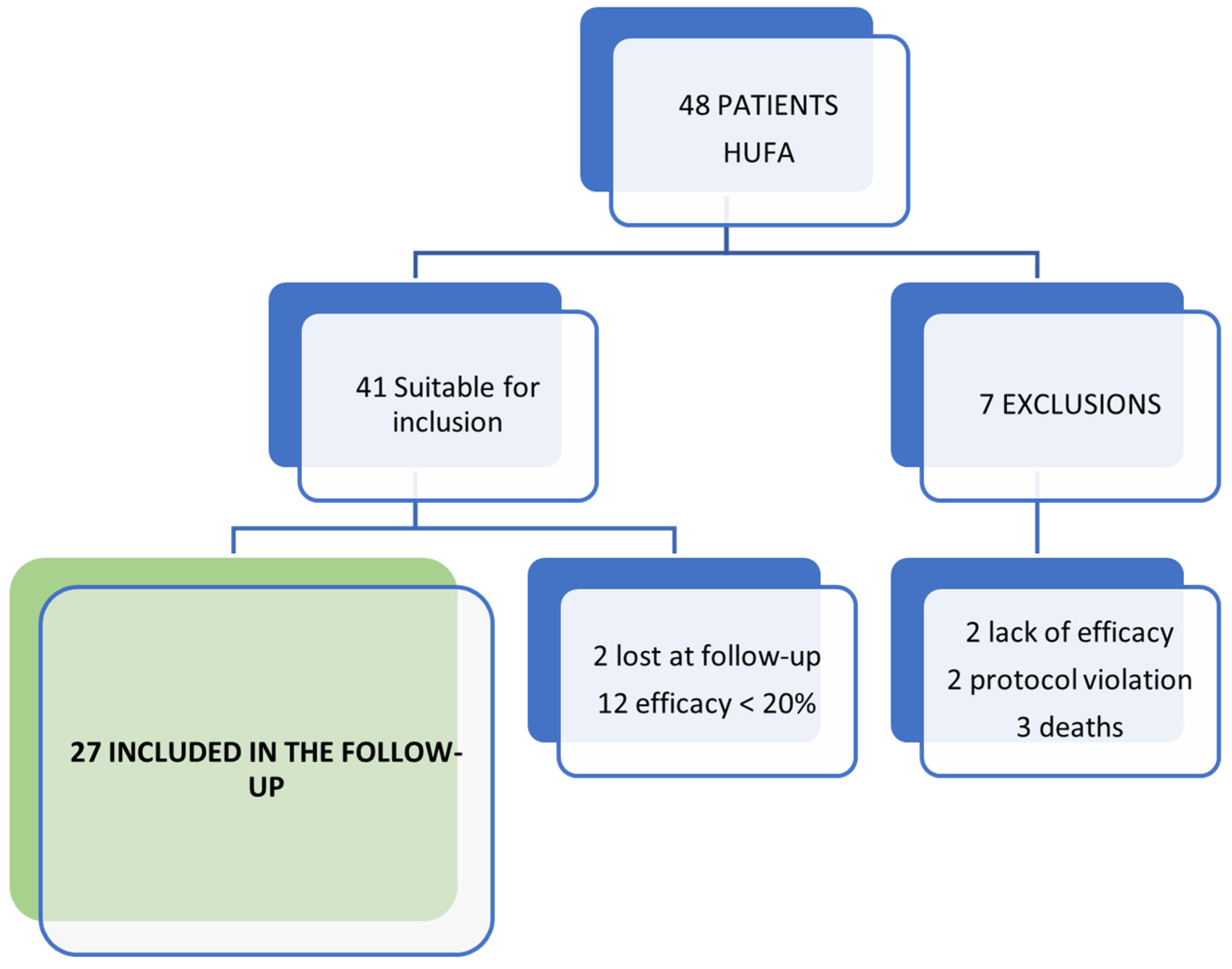

2.1. Participants and Study Design

2.2. Statistical Analysis

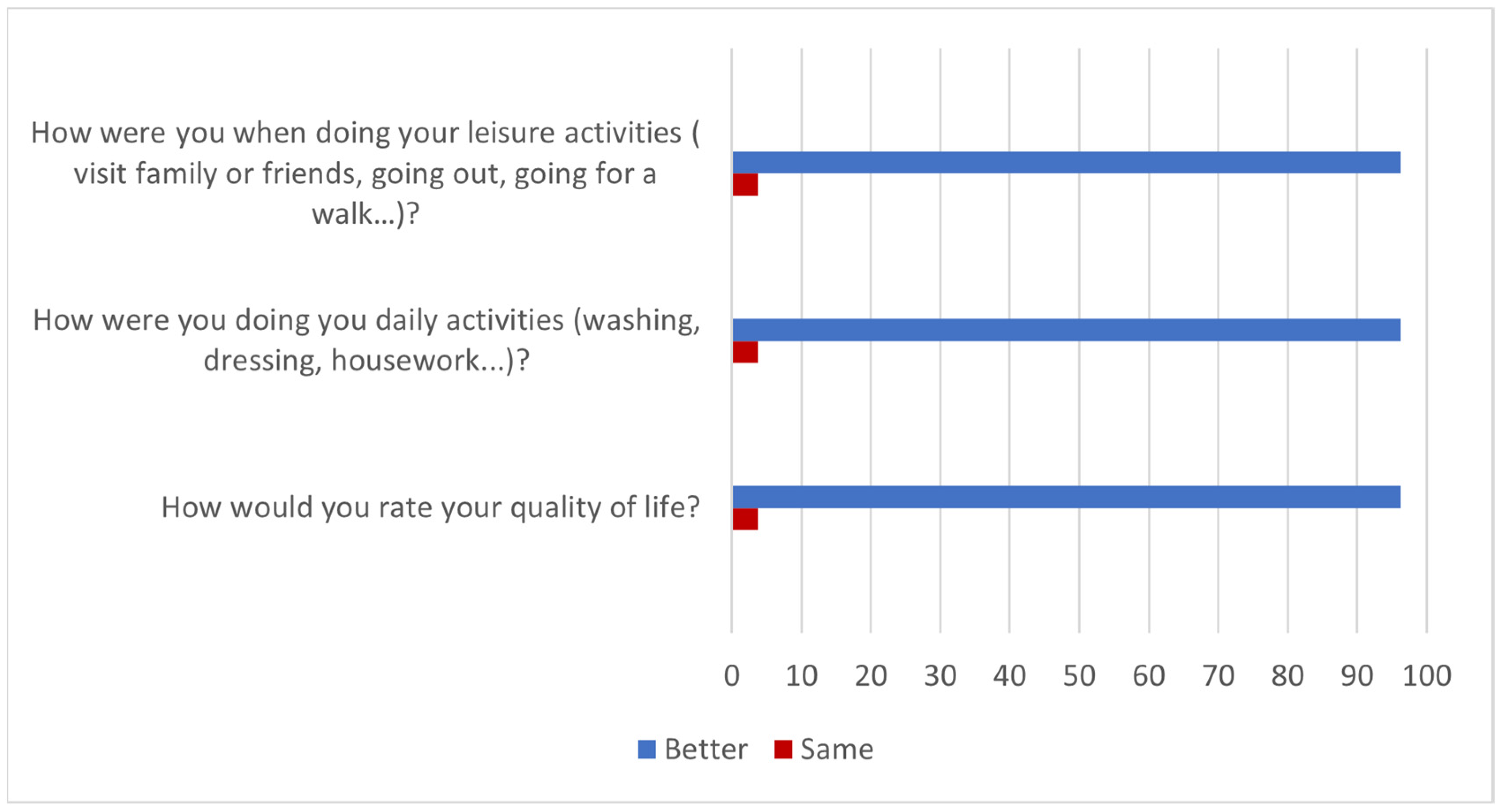

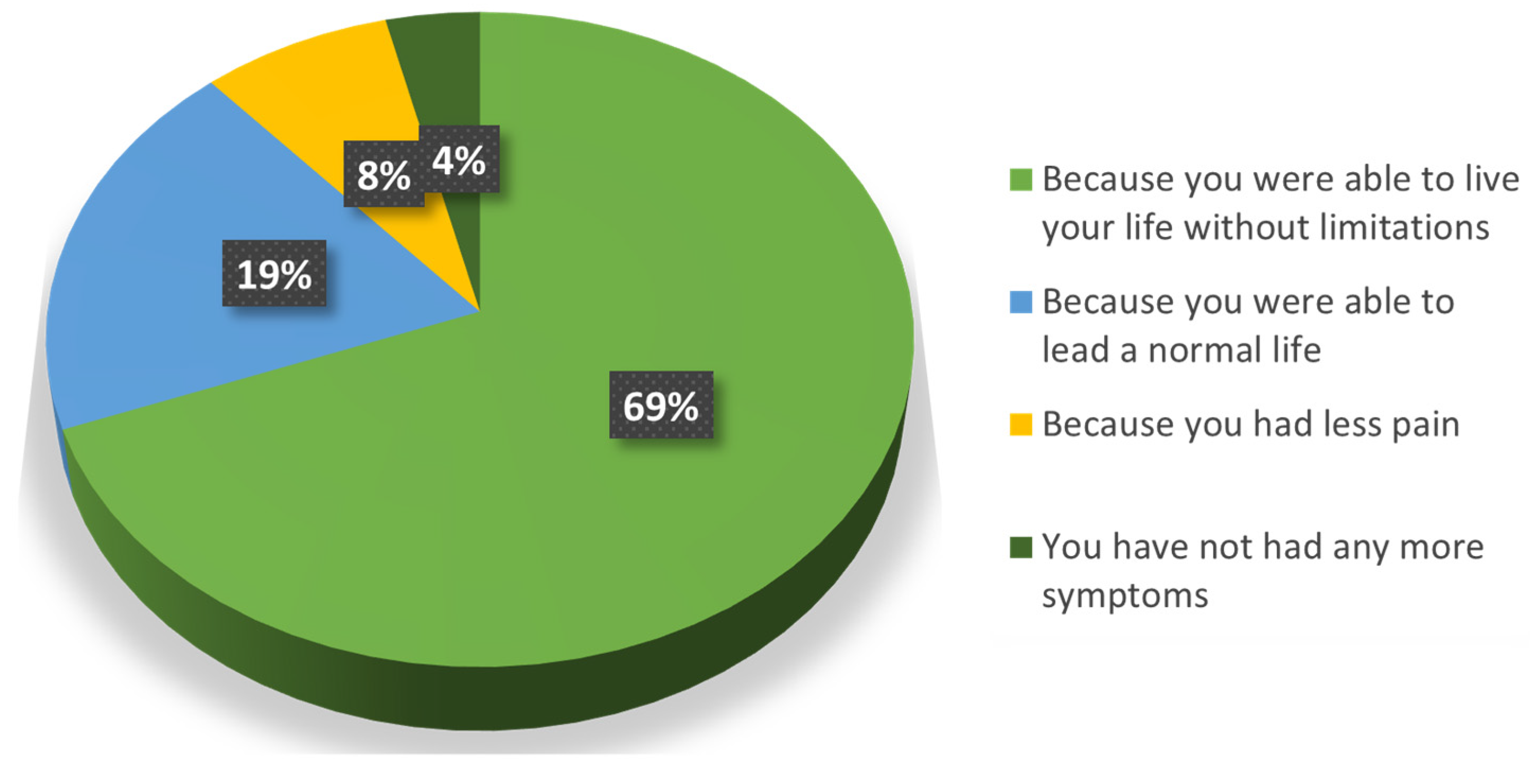

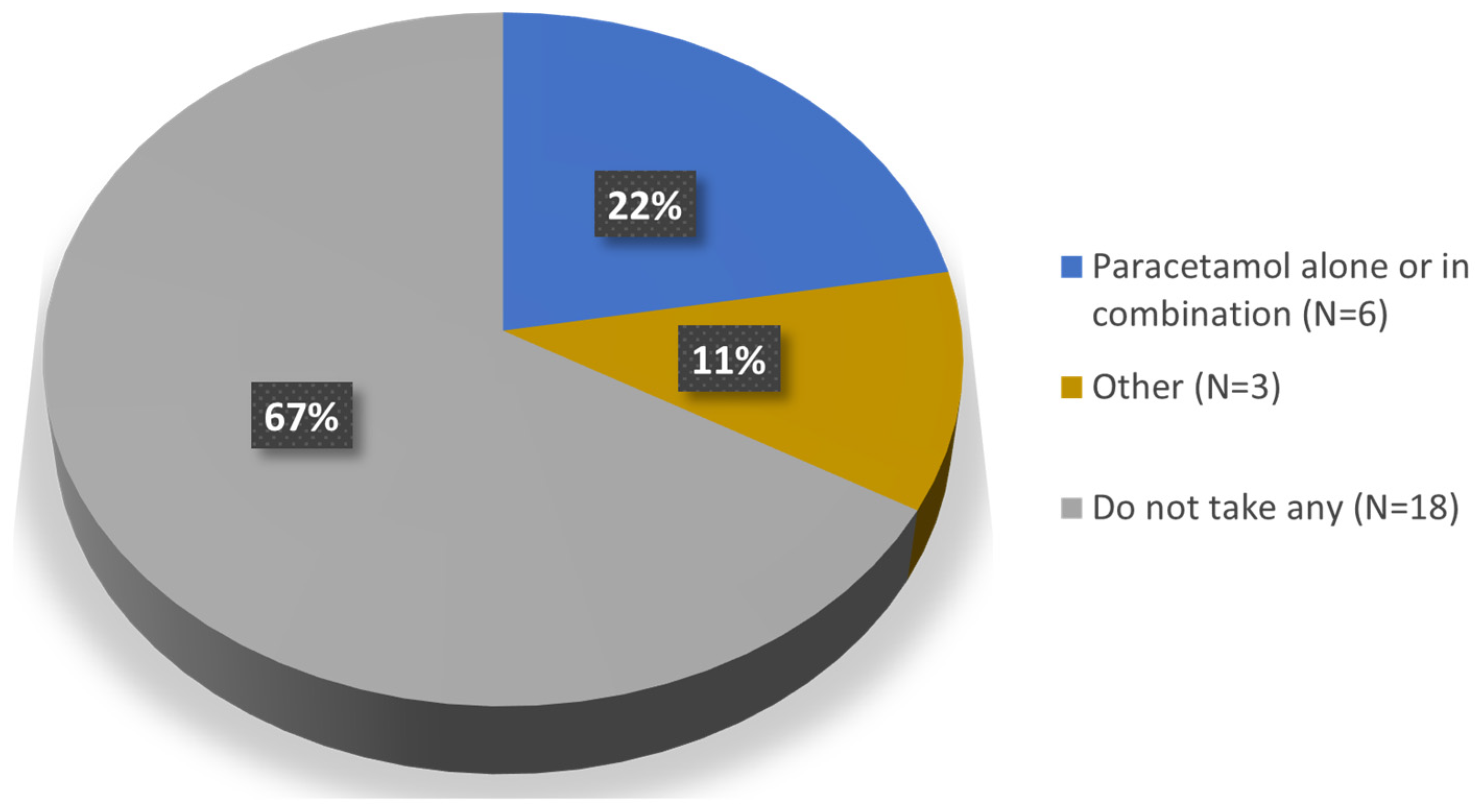

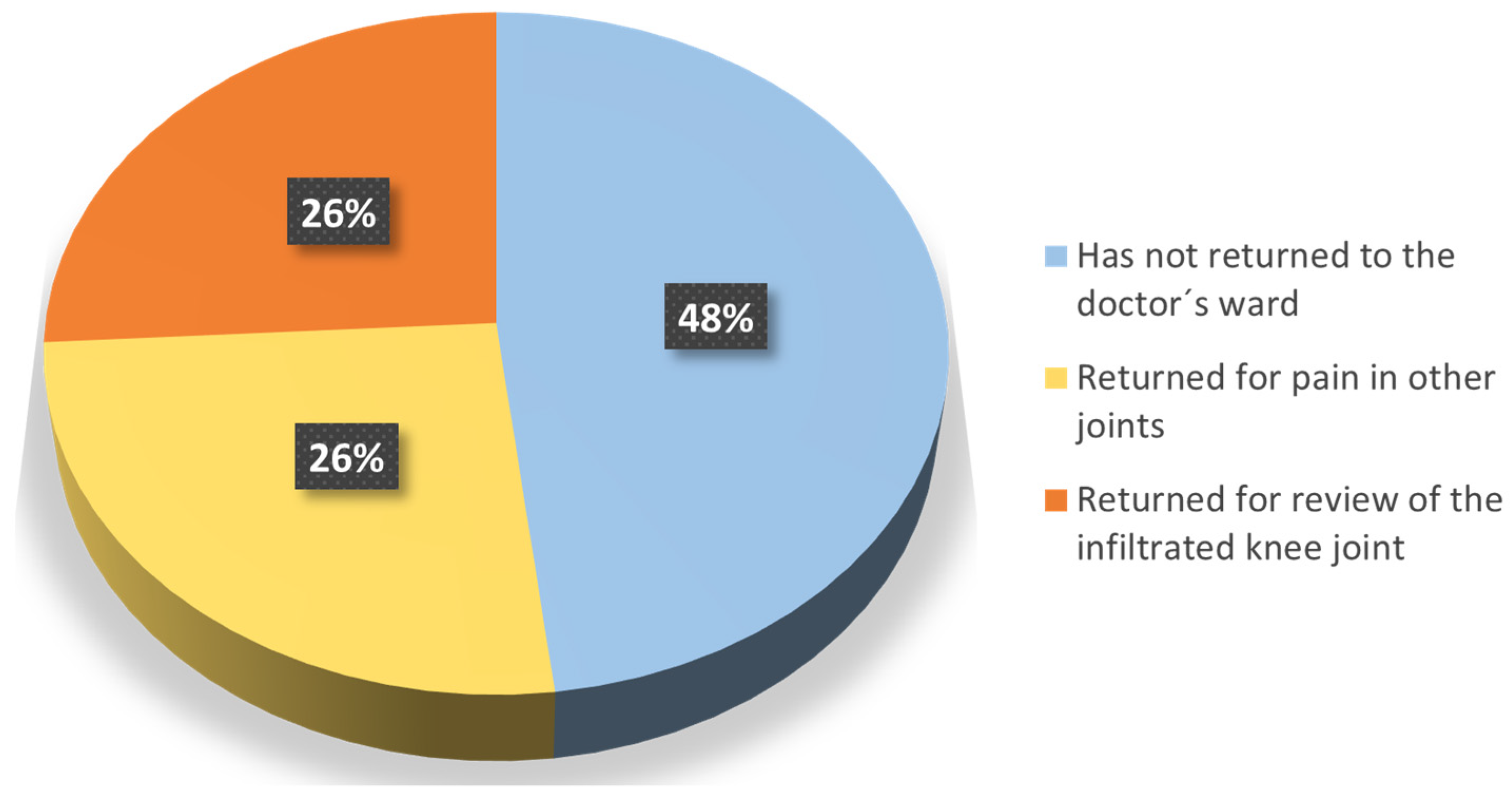

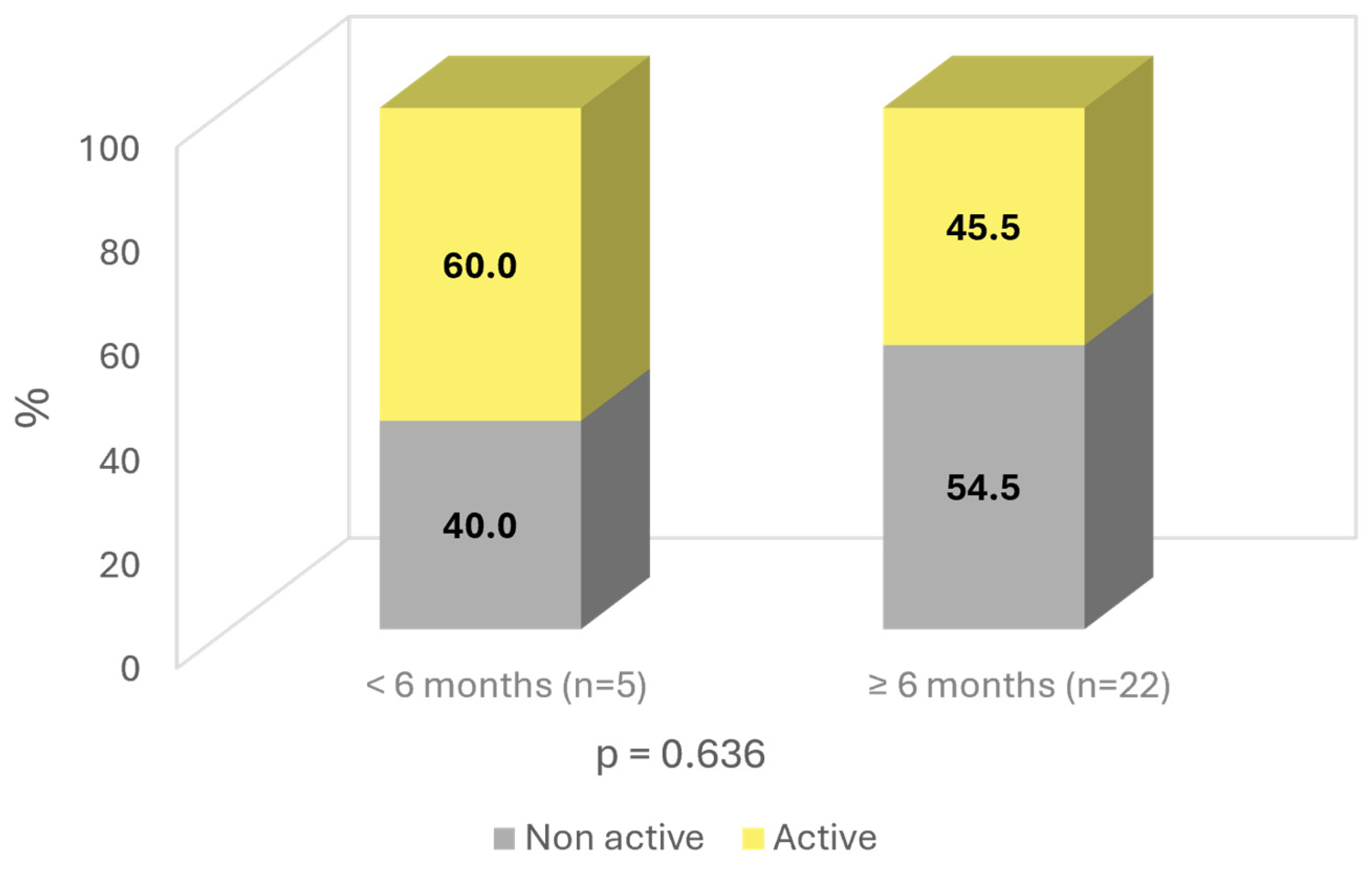

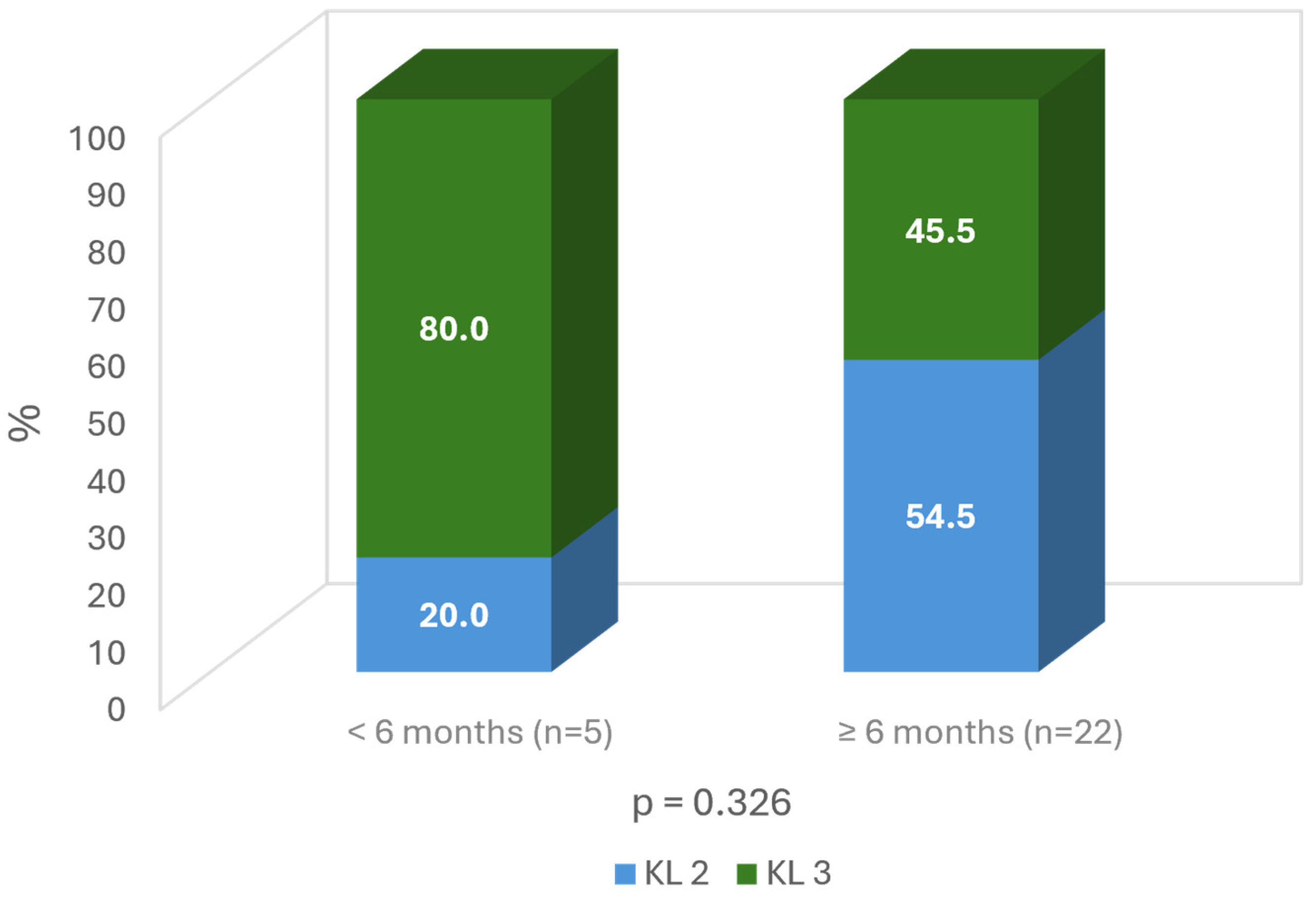

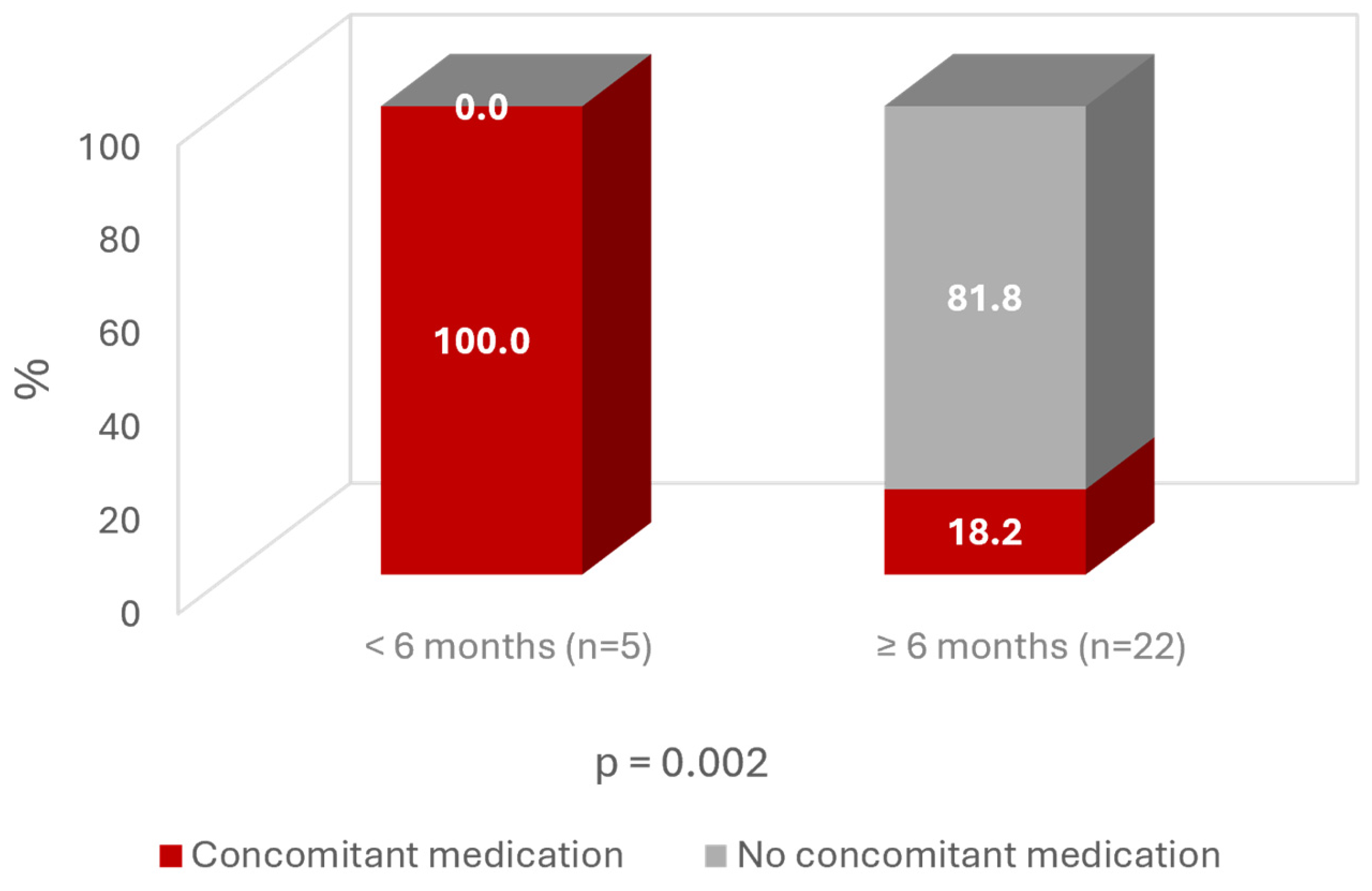

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hunter, D.J.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019, 393, 1745–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; He, L.; Ma, C.; Zhao, Z. Burden of Knee Osteoarthritis in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990–2019: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Arthritis Care Res. 2023, 75, 2489–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Culbreth, G.T.; Haile, L.M.; Rafferty, Q.; Lo, J.; Fukutaki, K.G.; A Cruz, J.; E Smith, A.; Vollset, S.E.; Brooks, P.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2020 and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023, 5, e508–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Castro-Dominguez, F.; Migliore, A.; Naredo, E.; Largo, R.; Reginster, J.Y. Systemic osteoarthritis: The difficulty of categorically naming a continuous condition. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakowski, P.; Rejniak, A.; Sobczyk, J.; Karpiński, R. Cartilage Integrity: A Review of Mechanical and Frictional Properties and Repair Approaches in Osteoarthritis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudaric, L.; Dumic-Cule, I.; Divjak, E.; Cengic, T.; Brkljacic, B.; Ivanac, G. Bone Remodeling in Osteoarthritis—Biological and Radiological Aspects. Medicina 2023, 59, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.; Awad, M.E.; Hamrick, M.W.; Hunter, M.; Fulzele, S. Recent advances in hyaluronic acid based therapy for osteoarthritis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, A.; Gigliucci, G.; Alekseeva, L.; Avasthi, S.; Bannuru, R.R.; Chevalier, X.; Conrozier, T.; Crimaldi, S.; Damjanov, N.; de Campos, G.C.; et al. Treat-to-target strategy for knee osteoarthritis. International technical expert panel consensus and good clinical practice statements. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2019, 11, 1759720X19893800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L. Osteoarthritis of the Knee. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavín, C.; Blanco, F.J.; Pablos, J.L.; A Caracuel, M.; Rosas, J.; Gómez-Barrena, E.; Navarro, F.; Coronel, M.P.; Gimeno, M. One-year, efficacy and safety open label study, with a single injection of a new hyaluronan for knee oa: The soya trial. J. Pain. Res. 2021, 14, 2229–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, F.R.; Marques, M.R.C.; Costa, V.C.; Santos, G.S.; Martins, R.A.; Santos, M.d.S.; Santana, M.H.A.; Nallakumarasamy, A.; Jeyaraman, M.; Lana, J.V.B.; et al. Intra-Articular Hyaluronic Acid in Osteoarthritis and Tendinopathies: Molecular and Clinical Approaches. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, R.D.; Manjoo, A.; Fierlinger, A.; Niazi, F.; Nicholls, M. The mechanism of action for hyaluronic acid treatment in the osteoarthritic knee: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2015, 16, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.T.; Lin, J.; Chang, C.J.; Lin, Y.T.; Hou, S.M. Therapeutic effects of hyaluronic acid on osteoarthritis of the knee. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2004, 86, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, N.; Campbell, J.; Robinson, V.; Gee, T.; Bourne, R.; Wells, G. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 2006, CD005321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divine, J.G.; Zazulak, B.T.; Hewett, T.E. Viscosupplementation for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2007, 455, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Natov, N.S.; Dasi, U.R.; Schmid, C.H.; McAlindon, T.E. Therapeutic trajectory following intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection in knee osteoarthritis–meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2011, 19, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.V.; Hsiao, M.Y.; Chen, W.S.; Wang, T.G.; Chien, K.L. Effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronic acid for ankle osteoarthritis treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L.E.; Block, J.E. US-approved intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections are safe and effective in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, saline-controlled trials. Clin. Med. Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013, 6, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojian, T.H.; Concoff, A.L.; Joy, S.M.; Hatzenbuehler, J.R.; Saulsberry, W.J.; Coleman, C.I. AMSSM scientific statement concerning viscosupplementation injections for knee osteoarthritis: Importance for individual patient outcomes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, M.; Bahrt, H.; Altman, R.D.; Bartels, E.M.; Juhl, C.B.; Bliddal, H.; Lund, H.; Christensen, R. Exploring reasons for the observed inconsistent trial reports on intra-articular injections with hyaluronic acid in the treatment of osteoarthritis: Meta-regression analyses of randomized trials. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016, 46, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, T.V.; Jüni, P.; Saadat, P.; Xing, D.; Yao, L.; Bobos, P.; Agarwal, A.; A Hincapié, C.; da Costa, B.R. Viscosupplementation for knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 378, e069722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.-W.; Kuang, M.-J.; Zhao, J.; Sun, L.; Lu, B.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J.-X.; Ma, X.-L. Efficacy and safety of intraarticular hyaluronic acid and corticosteroid for knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 39, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrotin, Y.; Chevalier, X.; Raman, R.; Richette, P.; Montfort, J.; Jerosch, J.; Baron, D.; Bard, H.; Carrillon, Y.; Migliore, A.; et al. EUROVISCO Guidelines for the Design and Conduct of Clinical Trials Assessing the Disease-Modifying Effect of Knee Viscosupplementation. Cartilage 2020, 11, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sarabia, F.; Coronel, P.; Collantes, E.; Navarro, F.J.; de la Serna, A.R.; Naranjo, A.; Gimeno, M.; Herrero-Beaumont, G.; on behalf of the AMELIA study group. A 40-month multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and carry-over effect of repeated intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid in knee osteoarthritis: The AMELIA project. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1957–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Bhandari, M.; Grant, J.; Bedi, A.; Trojian, T.; Johnson, A.; Schemitsch, E. A Systematic Review of Current Clinical Practice Guidelines on Intra-articular Hyaluronic Acid, Corticosteroid, and Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection for Knee Osteoarthritis: An International Perspective. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211030272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheu, E.; Rannou, F.; Reginster, J.Y. Efficacy and safety of hyaluronic acid in the management of osteoarthritis: Evidence from real-life setting trials and surveys. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016, 45, S28–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council–of 5 April 2017–on Medical Devices, Amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and Repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC; European Union: Luxembourg, 2017.

- Delanois, R.E.; Sax, O.C.; Chen, Z.; Cohen, J.M.; Callahan, D.M.; Mont, M.A. Biologic Therapies for the Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: An Updated Systematic Review. J. Arthroplast. 2022, 37, 2480–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevsevar, D.S.; Shores, P.B.; Mullen, K.; Schulte, D.M.; Brown, G.A.; Cummins, D.S. Mixed Treatment Comparisons for Nonsurgical Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Network Meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2018, 26, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannuru, R.R.; Schmid, C.H.; Kent, D.M.; Vaysbrot, E.E.; Wong, J.B.; McAlindon, T.E. Comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGettigan, P.; Henry, D. Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs That Elevate Cardiovascular Risk: An Examination of Sales and Essential Medicines Lists in Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanas, A.; Tornero, J.; Zamorano, J.L. Assessment of gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risk in patients with osteoarthritis who require NSAIDs: The LOGICA study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Driest, J.J.; Schiphof, D.; De Wilde, M.; Bindels, P.J.E.; Van Der Lei, J.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A. Opioid prescriptions in patients with osteoarthritis: A population-based cohort study. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demik, D.E.; Bedard, N.A.; Dowdle, S.B.; Burnett Bs, R.A.; Mchugh, M.A.; Callaghan, J.J. Are We Still Prescribing Opioids for Osteoarthritis? J. Arthroplast. 2017, 32, 3578–3582.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrozier, T.; Diraçoglù, D.; Monfort, J.; Chevalier, X.; Bard, H.; Baron, D.; Jerosch, J.; Migliore, A.; Richette, P.; Henrotin, Y. EUROVISCO Good Practice Recommendations for a First Viscosupplementation in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Cartilage 2023, 14, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, R.; Lim, S.; Steen, R.G.; Dasa, V. Hyaluronic acid injections are associated with delay of total knee replacement surgery in patients with knee osteoarthritis: Evidence from a large U.S. health claims database. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, R.; Hackel, J.; Niazi, F.; Shaw, P.; Nicholls, M. Efficacy and safety of repeated courses of hyaluronic acid injections for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2018, 48, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkani, S.; Courties, A.; Eymard, F.; Latourte, A.; Richette, P.; Berenbaum, F.; Sellam, J.; Louati, K. Time to Total Knee Arthroplasty after Intra-Articular Hyaluronic Acid or Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasa, V.; Lim, S.; Heeckt, P. Real-World Evidence for Safety and Effectiveness of Repeated Courses of Hyaluronic Acid Injections on the Time to Knee Replacement Surgery. Am. J. Orthop. (Belle Mead NJ) 2018, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Variable | Included n = 27 |

|---|---|

| Sex female (n, [%]) | 18 (66.7%) |

| Age, mean (sd) | 69.0 (9.3) |

| Body mass index (BMI), mean (sd) | 26.4 (3.0) |

| Active working life (n [%]) | 13 (48.1%) |

| Kellgren–Lawrence grade 2/3 (n [%]) | 13 (48.1%)/14 (51.9%) |

| Pain in VAS at end of SOYA trial, mean (sd) | 19.1 (14.6) |

| Taking at least 1 drug (n [%]) | 15 (55.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gavín, C.; Sebastián, V.; Gimeno, M.; Coronel, P. Beyond Boundaries of a Trial: Post-Market Clinical Follow-Up of SOYA Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6308. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216308

Gavín C, Sebastián V, Gimeno M, Coronel P. Beyond Boundaries of a Trial: Post-Market Clinical Follow-Up of SOYA Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(21):6308. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216308

Chicago/Turabian StyleGavín, Carlos, Victoria Sebastián, Mercedes Gimeno, and Pilar Coronel. 2024. "Beyond Boundaries of a Trial: Post-Market Clinical Follow-Up of SOYA Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 21: 6308. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216308

APA StyleGavín, C., Sebastián, V., Gimeno, M., & Coronel, P. (2024). Beyond Boundaries of a Trial: Post-Market Clinical Follow-Up of SOYA Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(21), 6308. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216308