Hemochromatosis—How Not to Overlook and Properly Manage “Iron People”—A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

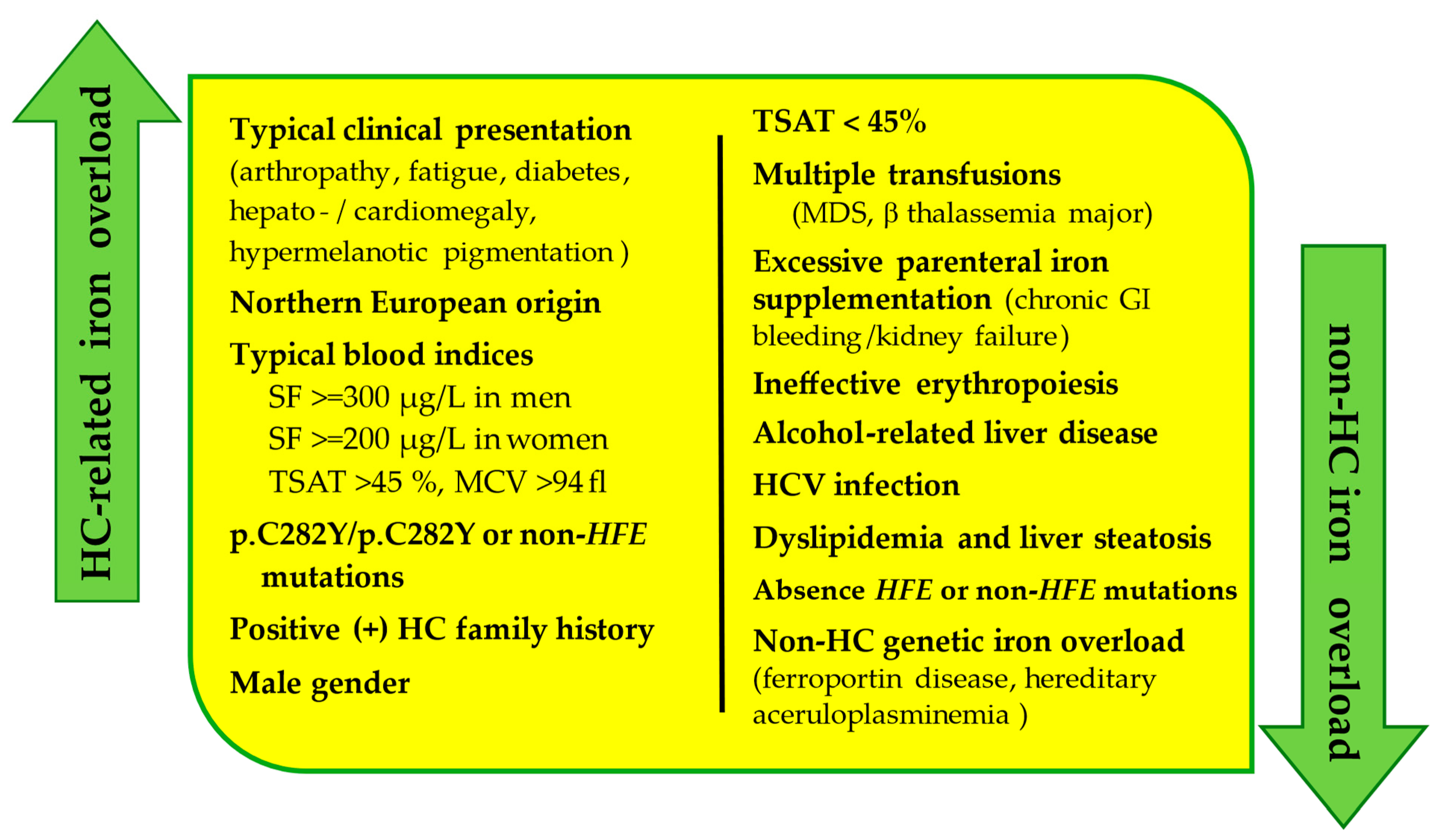

Body Iron Homeostasis and Risk Factors of Iron Overload

- (a)

- HFE p.C282Y homozygosity—the greatest risk factor;

- (b)

- positive family history for HC in the first-line relatives;

- (c)

- Northern European ethnicity—the disease is less prevalent in populations of Afro-American, Hispanic, and Asian origin;

- (d)

- male gender—men are susceptible to developing HC symptoms at an earlier age; however, females’ risk increases after menopause or a hysterectomy.

2. Gene Mutations in Hemochromatosis

3. The Current Classification of Hemochromatosis

4. Clinical Presentation of Hemochromatosis Regardless of Phlebotomy Treatment

4.1. Hemochromatosis and the Skeletomuscular System

4.2. Hemochromatosis and the Central Nervous System

4.3. Hemochromatosis and the Liver

4.4. Hemochromatosis and the Cardiovascular System

4.5. Hemochromatosis and the Endocrine System

4.6. Hemochromatosis and the Skin

5. Diagnostic Approach to the Patient with Iron Overload Suspicion

5.1. Blood Tests

- Serum transferrin saturation (TSAT)—is calculated as the ratio between serum iron and total iron-binding capacity (TIBC). The higher-than-normal value of TSAT (above 45%) remains the earliest disease indicator present in all hemochromatosis subtypes [24]. However, increased TSAT is also observed in other disorders (e.g., hemolysis, cytolysis) or decreased blood transferrin concentration (e.g., hepatocellular failure, proteinuria, malnutrition, genetic alterations) [73]. Normal or even lower TSAT values can be observed in patients with ferroportin disease or hereditary aceruloplasminemia despite overt iron overload [74,75].

- Serum ferritin level (SF)—is a commonly used diagnostic marker for the evaluation of iron storage in the body, although not very accurate [76]. The concentration of ferritin in the blood is influenced by many factors, as it is an acute-phase protein. Elevated SF levels (above 300 μg/L in men and postmenopausal women; above 200 μg/L in premenopausal women) require precise explanation before they are assigned to iron overload. Other conditions of hyperferritinemia, such as metabolic syndrome, alcoholism, inflammation, and marked cytolysis, should be ruled out [12]. Nevertheless, SF is an important prognostic factor in patients with HC. It is a predictor of advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with previously diagnosed hemochromatosis.

5.2. Genetic Testing

5.3. Additional Diagnostic Assessment for Hemochromatosis

- Liver enzymes and function tests—the pattern of liver function alterations helps monitor liver damage in the course of HC.

- Liver biopsy—determining the hepatic iron concentration (HIC) is rarely required to establish a final HC diagnosis; therefore, currently, genetic examination and imaging testing have replaced liver biopsy. Occasionally, it may be used to confirm or exclude other co-existing chronic liver diseases and to determine the degree of hepatic fibrosis, especially in cases with p.C282Y homozygosity and SF above 1000 ng/mL. HIC assessment may also be indicated in cases of suspected genetic iron overload with negative results towards common mutations including p.C282Y, p.H63D, and p.S65C. In remaining cases, liver biopsy is an option for individual consideration [81]. HIC assessed in a proper quality biopsy sample that is sample gross weight equal to or above 1 mg dry weight remains an accurate measure of entire hepatic iron concentration [82].

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—the reference imaging technique for the evaluation and quantification of HIC; a noninvasive and accurate alternative to a liver biopsy with an excellent correlation between both aforementioned procedures; useful for identification of iron overload, its rating, and the assessment of treatment results [83,84].

- Superconducting quantum interference device biomagnetic liver susceptometry (SQUID-BLS)—a noninvasive diagnostic device with very limited availability, used for HIC assessment; since hepatic iron can change its magnetic susceptibility, SQUID-BLS can quantify liver magnetic susceptibility and therefore determine liver iron concentration [80,85]. The procedure is available in very few specialized centers only.

6. Screening of Healthy People for Hemochromatosis

7. Treatment of Hemochromatosis

7.1. Phlebotomy—The First-Line Treatment for Iron Depletion

7.2. Erythrocytapheresis as an Alternative to Phlebotomy

7.3. Iron Chelators as a Therapeutic Alternative in Hemochromatosis

7.4. Proton Pump Inhibitors—An Adjunct Therapy for Hemochromatosis?

7.5. Liver Transplantation for Hemochromatosis

7.6. Recommended Lifestyle and Diet Modifications in Patients with Hemochromatosis

- withdrawal of additional iron sources such as iron supplements, iron-containing multivitamins, and iron-fortified foods and drinks (e.g., breakfast cereals, sports energy bars, etc.);

- recommendation of a varied vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, or flexitarian diet;

- avoidance of vitamin C supplements which increase iron absorption, but there is no need to restrict natural vitamin C in their diet (fruit and vegetables); fruit juices should be consumed between meals;

- recommendation of complete alcohol abstinence as its hepatotoxic impact aggravates liver damage; there is no safe alcohol amount;

8. Hemochromatosis in Women—Pregnancy and Fertility Issues

9. Future Directions in Hemochromatosis

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brissot, P.; Cavey, T.; Ropert, M.; Gaboriau, F.; Loréal, O. Hemochromatosis: A Model of Metal-Related Human Toxicosis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 2007–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, B.R. Hemochromatosis: Discovery of the HFE Gene. MO Med. 2012, 109, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Von Recklinghausen: Uber Haemochromatose. Taggeblatt der 62 Versammlung Deutscher Naturforscher and Aerzte in Heidelberg—Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?journal=Tagebl+Versamml+Natur+%C3%84rzte+Heidelberg&title=%C3%9Cber+Hamochromatose&author=FD+von+Recklinghausen&volume=62&publication_year=1889&pages=324& (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Feder, J.N.; Gnirke, A.; Thomas, W.; Tsuchihashi, Z.; Ruddy, D.A.; Basava, A. The Discovery of the New Haemochromatosis Gene. J. Hepatol. 2003, 38, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girelli, D.; Busti, F.; Brissot, P.; Cabantchik, I.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Porto, G. Hemochromatosis Classification: Update and Recommendations by the BIOIRON Society. Blood 2022, 139, 3018–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, R.E.; Ponka, P. Iron Overload in Human Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Hepcidin and Iron Homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron Metabolism and Iron Disorders Revisited in the Hepcidin Era. Haematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muckenthaler, M.U.; Rivella, S.; Hentze, M.W.; Galy, B. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell 2017, 168, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A. Iron in Health and Disease: An Update. Indian. J. Pediatr. 2020, 87, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissot, P.; Pietrangelo, A.; Adams, P.C.; de Graaff, B.; McLaren, C.E.; Loréal, O. Haemochromatosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altés, A.; Sanz, C.; Bruguera, M. Hemocromatosis hereditaria. Problemas en el diagnóstico y tratamiento. Med. Clínica 2015, 144, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabata, T. Iron-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, C.; Miyazawa, T.; Miyazawa, T. Current Use of Fenton Reaction in Drugs and Food. Molecules 2022, 27, 5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomer, S.A.; Brown, K.E. Iron-Induced Liver Injury: A Critical Reappraisal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, A.B.; Samal, R.R.; Bhol, N.K.; Duttaroy, A.K. Cellular Red-Ox System in Health and Disease: The Latest Update. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G.J.; Bardou-Jacquet, E. Revisiting Hemochromatosis: Genetic vs. Phenotypic Manifestations. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cathcart, J.; Mukhopadhya, A. European Association for Study of the Liver (EASL) Clinical Practice Guidelines on Haemochromatosis. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.C.; Richard, L.; Weir, M.; Speechley, M. Survival and Development of Health Conditions after Iron Depletion Therapy in C282Y-Linked Hemochromatosis Patients. Can. Liver J. 2021, 4, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissot, P.; Troadec, M.-B.; Loréal, O. Intestinal Absorption of Iron in HFE-1 Hemochromatosis: Local or Systemic Process? J. Hepatol. 2004, 40, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, J.C.; McLaren, C.E.; Chen, W.; Ramm, G.A.; Anderson, G.J.; Powell, L.W.; Subramaniam, V.N.; Adams, P.C.; Phatak, P.D.; Gurrin, L.C.; et al. Cirrhosis in Hemochromatosis: Independent Risk Factors in 368 HFE p.C282Y Homozygotes. Ann. Hepatol. 2018, 17, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowdley, K.V.; Brown, K.E.; Ahn, J.; Sundaram, V. ACG Clinical Guideline: Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 1202–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancado, R.D.; Alvarenga, A.M.; Santos, P.C.J. HFE Hemochromatosis: An Overview about Therapeutic Recommendations. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther. 2022, 44, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turshudzhyan, A.; Wu, D.C.; Wu, G.Y. Primary Non-HFE Hemochromatosis: A Review. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on Haemochromatosis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 479–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, D.H.G.; Ramm, G.A.; Bridle, K.R.; Nicoll, A.J.; Delatycki, M.B.; Olynyk, J.K. Clinical Practice Guidelines on Hemochromatosis: Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatol. Int. 2023, 17, 522–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delatycki, M.B.; Powell, L.W.; Allen, K.J. Hereditary Hemochromatosis Genetic Testing of At-Risk Children: What Is the Appropriate Age? Genet. Test. 2004, 8, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, S.F.; Roberts, C.; Paulus, R. Hereditary Hemochromatosis: Rapid Evidence Review. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 104, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Turbiville, D.; Du, X.; Yo, J.; Jana, B.R.; Dong, J. Iron Overload in an HFE Heterozygous Carrier: A Case Report and Literature Review. Lab. Med. 2019, 50, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonna, R.F.; Haddadin, R.; Iqbal, H.; Gemil, H. A Rare Case of Heterozygous C282Y Mutation Causing Hereditary Hemochromatosis with Acute Pancreatitis. Cureus 2024, 16, e52584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, H.R. Hemochromatosis and arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1964, 7, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, A.; Prideaux, A.; Kiely, P. Haemochromatosis: Unexplained Metacarpophalangeal or Ankle Arthropathy Should Prompt Diagnostic Tests: Findings from Two UK Observational Cohort Studies. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 46, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calori, S.; Comisi, C.; Mascio, A.; Fulchignoni, C.; Pataia, E.; Maccauro, G.; Greco, T.; Perisano, C. Overview of Ankle Arthropathy in Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, P.C.; Kertesz, A.E.; Valberg, L.S. Clinical Presentation of Hemochromatosis: A Changing Scene. Am. J. Med. 1991, 90, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Kempis, J. Arthropathy in Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2001, 13, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loughnan, R.; Ahern, J.; Tompkins, C.; Palmer, C.E.; Iversen, J.; Thompson, W.K.; Andreassen, O.; Jernigan, T.; Sugrue, L.; Dale, A.; et al. Association of Genetic Variant Linked to Hemochromatosis with Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measures of Iron and Movement Disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Rizek, P.; Sadikovic, B.; Adams, P.C.; Jog, M. Movement Disorders Associated with Hemochromatosis. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 43, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topiwala, A.; Wang, C.; Ebmeier, K.P.; Burgess, S.; Bell, S.; Levey, D.F.; Zhou, H.; McCracken, C.; Roca-Fernández, A.; Petersen, S.E.; et al. Associations between Moderate Alcohol Consumption, Brain Iron, and Cognition in UK Biobank Participants: Observational and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Findik, D.D.; Schafer, D.; Klein, E.; Timchenko, N.A.; Kulaksiz, H.; Clemens, D.; Fein, E.; Andriopoulos, B.; Pantopoulos, K.; Gollan, J. Alcohol Metabolism-Mediated Oxidative Stress down-Regulates Hepcidin Transcription and Leads to Increased Duodenal Iron Transporter Expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 22974–22982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Findik, D.D. Role of Alcohol in the Regulation of Iron Metabolism. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 4925–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivam, N.; Kim, Y.-J.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Kim, D.-K. Oxidative Stress, Genomic Integrity, and Liver Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, L.M.; Dixon, J.L.; Purdie, D.M.; Powell, L.W.; Crawford, D.H.G. Excess Alcohol Greatly Increases the Prevalence of Cirrhosis in Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology 2002, 122, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, P.C.; Agnew, S. Alcoholism in Hereditary Hemochromatosis Revisited: Prevalence and Clinical Consequences among Homozygous Siblings. Hepatology 1996, 23, 724–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvi, A.T.; Santiago, L.E.; Nadeem, Z.; Chaudhry, A. Fulminant Hepatic Failure with Minimal Alcohol Consumption in a 25-Year-Old Female With Hereditary Hemochromatosis: A Rare Case. Cureus 2023, 15, e44544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kew, M.C. Hepatic Iron Overload and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2014, 3, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, B.; Pammer, L.M.; Pfeifer, B.; Neururer, S.; Troppmair, M.R.; Panzer, M.; Wagner, S.; Pertler, E.; Gieger, C.; Kronenberg, F.; et al. Penetrance, Cancer Incidence and Survival in HFE Haemochromatosis-A Population-Based Cohort Study. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero, J.A.; Kulik, L.M.; Sirlin, C.B.; Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S.; Abecassis, M.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Heimbach, J.K. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 68, 723–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kaur, H.; Lerner, R.G.; Patel, R.; Rafiyath, S.M.; Singh Lamba, G. Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Non-Cirrhotic Liver Without Evidence of Iron Overload in a Patient with Primary Hemochromatosis. Review. J. Gastrointest. Canc 2012, 43, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardou-Jacquet, E.; Morandeau, E.; Anderson, G.J.; Ramm, G.A.; Ramm, L.E.; Morcet, J.; Bouzille, G.; Dixon, J.; Clouston, A.D.; Lainé, F.; et al. Regression of Fibrosis Stage with Treatment Reduces Long-Term Risk of Liver Cancer in Patients with Hemochromatosis Caused by Mutation in HFE. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1851–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniłowicz-Szymanowicz, L.; Świątczak, M.; Sikorska, K.; Starzyński, R.R.; Raczak, A.; Lipiński, P. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Clinical Implications of Hereditary Hemochromatosis—The Cardiological Point of View. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seferović, P.M.; Polovina, M.; Bauersachs, J.; Arad, M.; Ben Gal, T.; Lund, L.H.; Felix, S.B.; Arbustini, E.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Farmakis, D.; et al. Heart Failure in Cardiomyopathies: A Position Paper from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 553–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozpoznanie i Leczenie Hemochromatozy Dziedzicznej. Podsumowanie Wytycznych American College of Gastroenterology (AGA). Available online: http://www.mp.pl/social/article/260811 (accessed on 18 February 2024).

- Cortés, P.; Elsayed, A.A.; Stancampiano, F.F.; Barusco, F.M.; Shapiro, B.P.; Bi, Y.; Heckman, M.G.; Peng, Z.; Kempaiah, P.; Palmer, W.C. Clinical and Genetic Predictors of Cardiac Dysfunction Assessed by Echocardiography in Patients with Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 40, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, P.K.; Patel, S.C.; Shreya, D.; Zamora, D.I.; Patel, G.S.; Grossmann, I.; Rodriguez, K.; Soni, M.; Sange, I. Hereditary Hemochromatosis: A Cardiac Perspective. Cureus 2021, 13, e20009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.-H.; Fefelova, N.; Pamarthi, S.H.; Gwathmey, J.K. Molecular Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Relevance to Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, M.J.; Powell, L.W.; Dixon, J.L.; Ramm, G.A. Clinical Cofactors and Hepatic Fibrosis in Hereditary Hemochromatosis: The Role of Diabetes Mellitus. Hepatology 2012, 56, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altamura, S.; Müdder, K.; Schlotterer, A.; Fleming, T.; Heidenreich, E.; Qiu, R.; Hammes, H.-P.; Nawroth, P.; Muckenthaler, M.U. Iron Aggravates Hepatic Insulin Resistance in the Absence of Inflammation in a Novel Db/Db Mouse Model with Iron Overload. Mol. Metab. 2021, 51, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.V.; Lorenzo, F.R.; McClain, D.A. Iron and the Pathophysiology of Diabetes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2023, 85, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asberg, A.; Hveem, K.; Thorstensen, K.; Ellekjter, E.; Kannelønning, K.; Fjøsne, U.; Halvorsen, T.B.; Smethurst, H.B.; Sagen, E.; Bjerve, K.S. Screening for Hemochromatosis: High Prevalence and Low Morbidity in an Unselected Population of 65,238 Persons. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 36, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutler, E.; Felitti, V.J.; Koziol, J.A.; Ho, N.J.; Gelbart, T. Penetrance of 845G--> A (C282Y) HFE Hereditary Haemochromatosis Mutation in the USA. Lancet 2002, 359, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.J.; Gurrin, L.C.; Constantine, C.C.; Osborne, N.J.; Delatycki, M.B.; Nicoll, A.J.; McLaren, C.E.; Bahlo, M.; Nisselle, A.E.; Vulpe, C.D.; et al. Iron-Overload-Related Disease in HFE Hereditary Hemochromatosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, G.D.; McLaren, C.E.; Adams, P.C.; Barton, J.C.; Reboussin, D.M.; Gordeuk, V.R.; Acton, R.T.; Harris, E.L.; Speechley, M.R.; Sholinsky, P.; et al. Clinical Manifestations of Hemochromatosis in HFE C282Y Homozygotes Identified by Screening. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 22, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.C.; Acton, R.T. Diabetes in HFE Hemochromatosis. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 9826930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelusi, C.; Gasparini, D.I.; Bianchi, N.; Pasquali, R. Endocrine Dysfunction in Hereditary Hemochromatosis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2016, 39, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkash, O.; Akram, M. Hereditary Hemochromatosis. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2015, 25, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chevrant-Breton, J.; Simon, M.; Bourel, M.; Ferrand, B. Cutaneous Manifestations of Idiopathic Hemochromatosis. Study of 100 Cases. Arch. Dermatol. 1977, 113, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varada, N.; Tun, K.M.; Chang, M.J.; Bomberger, S.; Calagari, R.; Varada, N.; Tun, K.M.; Chang, M.J.; Bomberger, S.; Calagari, R. A Rare Case of Hereditary Hemochromatosis Presenting with Porphyria Cutanea Tarda. Cureus 2023, 15, e41299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, M.V.; Ray, J.M.; Bacon, B.R. Sporadic Porphyria Cutanea Tarda as the Initial Manifestation of Hereditary Hemochromatosis. ACG Case Rep. J. 2019, 6, e00247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sredoja Tišma, V.; Bulimbašić, S.; Jaganjac, M.; Stjepandić, M.; Larma, M. Progressive Pigmented Purpuric Dermatitis and Alopecia Areata as Unusual Skin Manifestations in Recognizing Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2012, 20, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leung, B.; Lindley, L.; Cruz, P.D.; Cole, S.; Ayoade, K.O. Iron Screening in Alopecia Areata Patients May Catch Hereditary Hemochromatosis Early. Cutis 2022, 110, E30–E32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Senussi, N.H.; Fertrin, K.Y.; Kowdley, K.V. Iron Overload Disorders. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 1842–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont-Epinette, M.-P.; Delobel, J.-B.; Ropert, M.; Deugnier, Y.; Loréal, O.; Jouanolle, A.-M.; Brissot, P.; Bardou-Jacquet, E. Hereditary Hypotransferrinemia Can Lead to Elevated Transferrin Saturation and, When Associated to HFE or HAMP Mutations, to Iron Overload. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2015, 54, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montosi, G.; Donovan, A.; Totaro, A.; Garuti, C.; Pignatti, E.; Cassanelli, S.; Trenor, C.C.; Gasparini, P.; Andrews, N.C.; Pietrangelo, A. Autosomal-Dominant Hemochromatosis Is Associated with a Mutation in the Ferroportin (SLC11A3) Gene. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyajima, H. Aceruloplasminemia. Neuropathology 2015, 35, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruzzese, A.; Martino, E.A.; Mendicino, F.; Lucia, E.; Olivito, V.; Bova, C.; Filippelli, G.; Capodanno, I.; Neri, A.; Morabito, F.; et al. Iron Chelation Therapy. Eur. J. Haematol. 2023, 110, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu Yin, J.; Cussen, C.; Harrington, C.; Foskett, P.; Raja, K.; Ala, A. Guideline Review: European Association for the Study of Liver (EASL) Clinical Practice Guidelines on Haemochromatosis. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2023, 13, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissot, P.; Brissot, E. What’s Important and New in Hemochromatosis? Clin. Hematol. Int. 2020, 2, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milic, S.; Mikolasevic, I.; Orlic, L.; Devcic, E.; Starcevic-Cizmarevic, N.; Stimac, D.; Kapovic, M.; Ristic, S. The Role of Iron and Iron Overload in Chronic Liver Disease. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 2144–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinyopornpanish, K.; Tantiworawit, A.; Leerapun, A.; Soontornpun, A.; Thongsawat, S. Secondary Iron Overload and the Liver: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2023, 11, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, M.L.; Hickman, P.E.; Dahlstrom, J.E. The Changing Role of Liver Biopsy in Diagnosis and Management of Haemochromatosis. Pathology 2011, 43, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urru, S.A.M.; Tandurella, I.; Capasso, M.; Usala, E.; Baronciani, D.; Giardini, C.; Visani, G.; Angelucci, E. Reproducibility of Liver Iron Concentration Measured on a Biopsy Sample: A Validation Study in Vivo. Am. J. Hematol. 2015, 90, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golfeyz, S.; Lewis, S.; Weisberg, I.S. Hemochromatosis: Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Management of Hepatic Iron Overload with a Focus on MRI. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 12, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeder, S.B.; Yokoo, T.; França, M.; Hernando, D.; Alberich-Bayarri, Á.; Alústiza, J.M.; Gandon, Y.; Henninger, B.; Hillenbrand, C.; Jhaveri, K.; et al. Quantification of Liver Iron Overload with MRI: Review and Guidelines from the ESGAR and SAR. Radiology 2023, 307, e221856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobi, N.; Herich, L. Measurement of Liver Iron Concentration by Superconducting Quantum Interference Device Biomagnetic Liver Susceptometry Validates Serum Ferritin as Prognostic Parameter for Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Eur. J. Haematol. 2016, 97, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for HFE Hemochromatosis. J. Hepatol. 2010, 53, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savatt, J.M.; Johns, A.; Schwartz, M.L.B.; McDonald, W.S.; Salvati, Z.M.; Oritz, N.M.; Masnick, M.; Hatchell, K.; Hao, J.; Buchanan, A.H.; et al. Testing and Management of Iron Overload After Genetic Screening-Identified Hemochromatosis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2338995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzetti, E.; Kalafateli, M.; Thorburn, D.; Davidson, B.R.; Tsochatzis, E.; Gurusamy, K.S. Interventions for Hereditary Haemochromatosis: An Attempted Network Meta-Analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD011647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, P.; Altes, A.; Brissot, P.; Butzeck, B.; Cabantchik, I.; Cançado, R.; Distante, S.; Evans, P.; Evans, R.; Ganz, T.; et al. Therapeutic Recommendations in HFE Hemochromatosis for p.Cys282Tyr (C282Y/C282Y) Homozygous Genotype. Hepatol. Int. 2018, 12, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stussi, G.; Buser, A.; Holbro, A. Red Blood Cells: Exchange, Transfuse, or Deplete. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2019, 46, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rombout-Sestrienkova, E.; Brandts, L.; Koek, G.H.; van Deursen, C.T.B.M. Patients with Hereditary Hemochromatosis Reach Safe Range of Transferrin Saturation Sooner with Erythrocytaphereses than with Phlebotomies. J. Clin. Apher. 2022, 37, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundic, T.; Hervig, T.; Hannisdal, S.; Assmus, J.; Ulvik, R.J.; Olaussen, R.W.; Berentsen, S. Erythrocytapheresis Compared with Whole Blood Phlebotomy for the Treatment of Hereditary Haemochromatosis. Blood Transfus. 2014, 12, s84–s89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, R.; Melo, M.R.; de Moraes Bastos, R.; Santos, P.C.J.L.; Guerra-Shinohara, E.M.; Chiattone, C.; Ballas, S.K. Deferasirox in Patients with Iron Overload Secondary to Hereditary Hemochromatosis: Results of a 1-Yr Phase 2 Study. Eur. J. Haematol. 2015, 95, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entezari, S.; Haghi, S.M.; Norouzkhani, N.; Sahebnazar, B.; Vosoughian, F.; Akbarzadeh, D.; Islampanah, M.; Naghsh, N.; Abbasalizadeh, M.; Deravi, N. Iron Chelators in Treatment of Iron Overload. J. Toxicol. 2022, 2022, 4911205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomber, S.; Jain, P.; Sharma, S.; Narang, M. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Oral Iron Chelators and Their Novel Combination in Children with Thalassemia. Indian Pediatr. 2016, 53, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelucci, E. Another Step Forward in Iron Chelation Therapy. Acta Haematol. 2015, 134, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontoghiorghe, C.N.; Kontoghiorghes, G.J. New Developments and Controversies in Iron Metabolism and Iron Chelation Therapy. World J. Methodol. 2016, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchner, H.; Fontanarosa, P.B.; Golub, R.M. Evaluation of the Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy (TACT): The Scientific Process, Peer Review, and Editorial Scrutiny. JAMA 2013, 309, 1291–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mobarra, N.; Shanaki, M.; Ehteram, H.; Nasiri, H.; Sahmani, M.; Saeidi, M.; Goudarzi, M.; Pourkarim, H.; Azad, M. A Review on Iron Chelators in Treatment of Iron Overload Syndromes. Int. J. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell Res. 2016, 10, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanclooster, A.; van Deursen, C.; Jaspers, R.; Cassiman, D.; Koek, G. Proton Pump Inhibitors Decrease Phlebotomy Need in HFE Hemochromatosis: Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 678–680.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirweesh, A.; Anugwom, C.M.; Li, Y.; Vaughn, B.P.; Lake, J. Proton Pump Inhibitors Reduce Phlebotomy Burden in Patients with HFE-Related Hemochromatosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lymberopoulos, P.; Prakash, S.; Shaikh, A.; Bhatnagar, A.; Allam, A.K.; Goli, K.; Goss, J.A.; Kanwal, F.; Rana, A.; Kowdley, K.V.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes and Trends in Liver Transplantation for Hereditary Hemochromatosis in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2023, 29, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhail, M.J.W.; Khorsandi, S.E.; Abbott, L.; Al-Kadhimi, G.; Kane, P.; Karani, J.; O’Grady, J.; Heaton, N.; Bomford, A.; Suddle, A. Modern Outcomes Following Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Hereditary Hemochromatosis: A Matched Cohort Study. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 42, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, E.; Pantopoulos, K. Nutritional Aspects of Iron in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakrzewski, A.J.; Gajewska, J.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Załuski, D.; Zadernowska, A. Prevalence of Listeria Monocytogenes and Other Listeria Species in Fish, Fish Products and Fish Processing Environment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasagabaster, A.; Jiménez, E.; Lehnherr, T.; Miranda-Cadena, K.; Lehnherr, H. Bacteriophage Biocontrol to Fight Listeria Outbreaks in Seafood. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 145, 111682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahulcová, M.; Cverenkárová, K.; Koreneková, J.; Oravcová, A.; Koščová, J.; Bírošová, L. Occurrence of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Fish and Seafood from Slovak Market. Foods 2023, 12, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milman, N.T. Managing Genetic Hemochromatosis: An Overview of Dietary Measures, Which May Reduce Intestinal Iron Absorption in Persons with Iron Overload. Gastroenterol. Res. 2021, 14, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moirand, R.; Adams, P.C.; Bicheler, V.; Brissot, P.; Deugnier, Y. Clinical Features of Genetic Hemochromatosis in Women Compared with Men. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 127, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, M.; Belci, P.; Collo, A.; Prandi, V.; Pistone, E.; Martorana, M.; Gambino, R.; Bo, S. Gender Specific Medicine in Liver Diseases: A Point of View. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, C.; Zhang, J.; Goldenberg, I.; Gill, S.; Saeed, H.; Iyer, C.; Dunnigan, K. Maternal and Prenatal Outcomes of Hemochromatosis in Pregnancy: A Population-Based Study. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2023, 47, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotet, V.; Saliou, P.; Uguen, M.; L’Hostis, C.; Merour, M.-C.; Triponey, C.; Chanu, B.; Nousbaum, J.-B.; Le Gac, G.; Ferec, C. Do Pregnancies Reduce Iron Overload in HFE Hemochromatosis Women? Results from an Observational Prospective Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.V.; Olsson, I.A.S.; Porto, G.; Rodrigues, P.N. Hemochromatosis and Pregnancy: Iron Stores in the Hfe-/- Mouse Are Not Reduced by Multiple Pregnancies. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 298, G525–G529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayaf, K.; Gabbia, D.; Russo, F.P.; De Martin, S. The Role of Sex in Acute and Chronic Liver Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, S. Beyond the X Factor: Relevance of Sex Hormones in NAFLD Pathophysiology. Cells 2021, 10, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizzaro, D.; Crescenzi, M.; Di Liddo, R.; Arcidiacono, D.; Cappon, A.; Bertalot, T.; Amodio, V.; Tasso, A.; Stefani, A.; Bertazzo, V.; et al. Sex-Dependent Differences in Inflammatory Responses during Liver Regeneration in a Murine Model of Acute Liver Injury. Clin. Sci. 2018, 132, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamas, A.G. Primary Hereditary Haemochromatosis and Pregnancy. GastroHep 2023, 2023, e2674203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phatak, P.D.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; Kowdley, K.V. Hereditary Hemochromatosis: Time for Targeted Screening. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 149, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organ/System | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Skeletomuscular system | arthralgia, arthritis, chondrocalcinosis, reduced bone mineral density, fatigue, weakness |

| Central nervous system | lack of energy (lethargy), irritability, memory fog, mood swings, depression, anxiety, movement disorders, tremors |

| Liver | high liver enzymes, hepatosplenomegaly, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Cardiovascular system | cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, heart failure |

| Endocrine system | hypogonadism, testicular atrophy, reproductive disorders with loss of libido, impotence, amenorrhea, hyperglycemia, diabetes mellitus, hypopituitarism |

| Skin | bronze or gray skin tone (hypermelanotic pigmentation), hair loss, porphyria cutanea tarda (?) |

| Immune system | immune defects, infections |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szczerbinska, A.; Kasztelan-Szczerbinska, B.; Rycyk-Bojarzynska, A.; Kocki, J.; Cichoz-Lach, H. Hemochromatosis—How Not to Overlook and Properly Manage “Iron People”—A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133660

Szczerbinska A, Kasztelan-Szczerbinska B, Rycyk-Bojarzynska A, Kocki J, Cichoz-Lach H. Hemochromatosis—How Not to Overlook and Properly Manage “Iron People”—A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(13):3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133660

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzczerbinska, Agnieszka, Beata Kasztelan-Szczerbinska, Anna Rycyk-Bojarzynska, Janusz Kocki, and Halina Cichoz-Lach. 2024. "Hemochromatosis—How Not to Overlook and Properly Manage “Iron People”—A Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 13: 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133660

APA StyleSzczerbinska, A., Kasztelan-Szczerbinska, B., Rycyk-Bojarzynska, A., Kocki, J., & Cichoz-Lach, H. (2024). Hemochromatosis—How Not to Overlook and Properly Manage “Iron People”—A Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), 3660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133660