The Hidden Pandemic: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Trauma Cases Due to Domestic Violence Admitted to the Biggest Level-One Trauma Center in Austria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

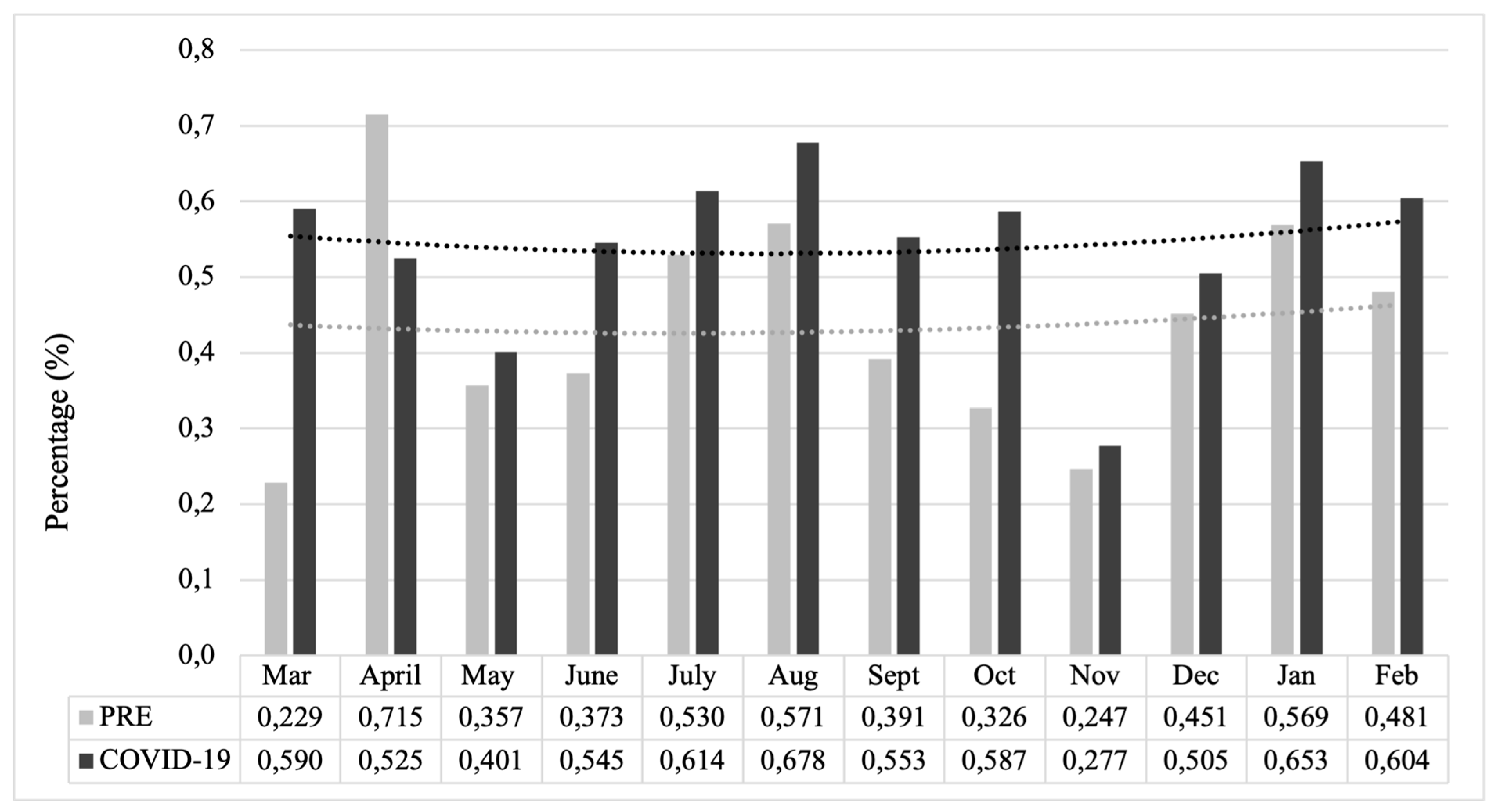

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akin, L.; Gözel, M.G. Understanding Dynamics of Pandemics. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50 (Suppl. S1), 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundeskanzleramt. Bundesregierung präsentiert aktuelle Beschlüsse zum Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.bundeskanzleramt.gv.at/bundeskanzleramt/nachrichten-der-bundesregierung/2020/bundesregierung-praesentiert-aktuelle-beschluesse-zum-coronavirus.html (accessed on 13 March 2020).

- Kawohl, W.; Nordt, C. COVID-19, Unemployment, and Suicide. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, M.A.; Caputo, F.; Ricci, P.; Sicilia, F.; De Aloe, L.; Bonetta, C.F.; Cordasco, F.; Scalise, C.; Cacciatore, G.; Zibetti, A.; et al. The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Domestic Violence: The Dark Side of Home Isolation during Quarantine. Med. Leg. J. 2020, 88, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleitzke, T.; Pumberger, M.; Gerlach, U.A.; Herrmann, C.; Slagman, A.; Henriksen, L.S.; von Mauchenheim, F.; Hüttermann, N.; Santos, A.N.; Fleckenstein, F.N.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Shutdown on Orthopedic Trauma Numbers and Patterns in an Academic Level I Trauma Center in Berlin, Germany. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.L.; Lindauer, M.; Farrell, M.E. A Pandemic within a Pandemic—Intimate Partner Violence during Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2302–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, C.F.; Burton, C.; Kosky, M. Considerations of the Impacts of COVID-19 on Domestic Violence in the United States. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2020, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kofman, Y.B.; Garfin, D.R. Home Is Not Always a Haven: The Domestic Violence Crisis amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychol. Trauma 2020, 12 (Suppl. S1), S199–S201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yenilmez, M.İ.; Çelik, O.B. Pandemics and Domestic Violence during COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sifat, R.I. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Domestic Violence in Bangladesh. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 53, 102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enarson, E. Violence against Women in Disasters: A Study of Domestic Violence Programs in the United States and Canada. Violence against Women 1999, 5, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, J.A.; Coffey, S.F.; Norris, F.H.; Tracy, M.; Clements, K.; Galea, S. Intimate Partner Violence and Hurricane Katrina: Predictors and Associated Mental Health Outcomes. Violence Vict. 2010, 25, 588–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, S. Violence against Women and Natural Disasters: Findings from Post-Tsunami Sri Lanka. Violence against Women 2010, 16, 902–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. What Is Domestic Abuse? Available online: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/What-Is-Domestic-Abuse (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Hegarty, K.; Hindmarsh, E.D.; Gilles, M.T. Domestic Violence in Australia: Definition, Prevalence and Nature of Presentation in Clinical Practice. Med. J. Aust. 2000, 173, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dam, B.A.F.M.; van der Sanden, W.J.M.; Bruers, J.J.M. Recognizing and Reporting Domestic Violence: Attitudes, Experiences and Behavior of Dutch Dentists. BMC Oral Health 2015, 15, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistik Austria. Jede dritte Frau von Gewalt betroffen. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/fileadmin/announcement/2022/11/20221125GewaltgegenFrauen.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- Bundesministerium Inneres. Polizeiliche Kriminalstatistik. Available online: https://bundeskriminalamt.at/501/ (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Beck, T.; Trawöger, I.; Riedl, D.; Lampe, A. Awareness training for domestic violence for medical professionals. Are they efficient too? Neuropsychiatr. Klin. Diagn. Ther. Rehabil. Organ Der Ges. Osterr. Nervenarzte Psychiater 2020, 34, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical University of Vienna. MedUni Vienna and University Hospital Vienna Stand in Solidarity against Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.meduniwien.ac.at/web/en/ueber-uns/news/news-im-november-2021/meduni-wien-und-akh-wien-setzen-ein-zeichen-gegen-gewalt-an-frauen/ (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Österreichisches Kranken- und Kuranstaltengesetz (KAKuG). § 8e (2011). Available online: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/eli/bgbl/1957/1/P8e/NOR40211924 (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- United Nations. Addressing the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Violence against Women and Girls. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/addressing-impact-covid-19-pandemic-violence-against-women-and-girls (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Nesset, M.B.; Gudde, C.B.; Mentzoni, G.E.; Palmstierna, T. Intimate Partner Violence during COVID-19 Lockdown in Norway: The Increase of Police Reports. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sediri, S.; Zgueb, Y.; Ouanes, S.; Ouali, U.; Bourgou, S.; Jomli, R.; Nacef, F. Women’s Mental Health: Acute Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Domestic Violence. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2020, 23, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.P.; Hawk, S.R.; Ripkey, C.E. Domestic Violence in Atlanta, Georgia Before and During COVID-19. Violence Gend. 2021, 8, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akel, M.; Berro, J.; Rahme, C.; Haddad, C.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Violence Against Women During COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP12284–NP12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.I.; Shabu, S.A.; M-Amen, K.M.; Hussain, S.S.; Kako, D.A.; Hinchliff, S.; Shabila, N.P. The Impact of COVID-19 Related Lockdown on the Prevalence of Spousal Violence Against Women in Kurdistan Region of Iraq. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP11811–NP11835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autonome Österreichische Frauenhäuser. Zahlen und Daten-Gewalt an Frauen in Österreich. Available online: https://www.aoef.at/index.php/zahlen-und-daten (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Lazzerini, M.; Barbi, E.; Apicella, A.; Marchetti, F.; Cardinale, F.; Trobia, G. Delayed Access or Provision of Care in Italy Resulting from Fear of COVID-19. Lancet. Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, e10–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakim, R.; Motreff, P.; Rangé, G. COVID-19 and STEMI. Ann. Cardiol. Angeiol. 2020, 69, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvori, M.; Elitzur, S.; Barg, A.; Barzilai-Birenboim, S.; Gilad, G.; Amar, S.; Toledano, H.; Toren, A.; Weinreb, S.; Goldstein, G.; et al. Delayed Diagnosis and Treatment of Children with Cancer during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 26, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valent, F. Road Traffic Accidents in Italy during COVID-19. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2022, 23, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahana, D.; Rathore, L.; Kumar, S.; Sahu, R.K.; Jain, A.K.; Tawari, M.K.; Borde, P.R. COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: A Cloud with a Silver Lining for the Road Traffic Accidents Pandemic. Neurol. India 2022, 70, 2432–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keays, G.; Friedman, D.; Gagnon, I. Injuries in the Time of COVID-19. Heal. Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Canada Res. Policy Pract. 2020, 40, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, D.; Frank, R.; Crevenna, R. The Impact of Lockdowns during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Work-Related Accidents in Austria in 2020. Wien. Klein. Wochenschr. 2022, 134, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundeskanzleramt. Integrationsbericht 2021 “Integration im Kontext der Coronapandemie”. Available online: https://www.bundeskanzleramt.gv.at/service/publikationen-aus-dem-bundeskanzleramt/publikationen-zu-integration/integrationsberichte.html (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Lerner, J.E.; Lee, J.J. Transgender and Gender Diverse (TGD) Asian Americans in the United States: Experiences of Violence, Discrimination, and Family Support. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP21165–NP21188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griner, S.B.; Vamos, C.A.; Thompson, E.L.; Logan, R.; Vázquez-Otero, C.; Daley, E.M. The Intersection of Gender Identity and Violence: Victimization Experienced by Transgender College Students. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 5704–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoloff, N.J.; Dupont, I. Domestic Violence at the Intersections of Race, Class, and Gender: Challenges and Contributions to Understanding Violence against Marginalized Women in Diverse Communities. Violence against Women 2005, 11, 38–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, D.; Harknett, K.; McLanahan, S. Intimate Partner Violence in the Great Recession. Demography 2016, 53, 471–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakidou, M.; Zalaf, A.; Christophorou, S.; Ruiz-Garcia, A.; Valanides, C. Longitudinal Fluctuations of National Help-Seeking Reports for Domestic Violence Before, During, and After the Financial Crisis in Cyprus. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP8333–NP8346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, T.; Miller, B.C.; Berry, E.H. Changes in Reports and Incidence of Child Abuse Following Natural Disasters. Child Abuse Negl. 2000, 24, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vora, M.; Malathesh, B.C.; Das, S.; Chatterjee, S.S. COVID-19 and Domestic Violence against Women. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 53, 102227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, D.; Zara, C. The Hidden Disaster: Domestic Violence in the Aftermath of Natural Disaster. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2013, 28, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Finanzen. FAQ: Das Corona-Hilfspaket der Österreichischen Bundesregierung. Available online: https://www.bmf.gv.at/public/top-themen/corona-hilfspaket-faq.html (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Eurostat. Data Brower. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/crim_hom_soff/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. Häusliche Gewalt im jahr 2022. Available online: https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/aktuelles/presse/pressemitteilungen/haeusliche-gewalt-im-jahr-2022-opferzahl-um-8-5-prozent-gestiegen-dunkelfeld-wird-staerker-ausgeleuchtet-228400 (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Autonome Österreichische Frauenhäuser. Infoblatt über Femizide in Österreich. Available online: https://www.aoef.at/images/06_infoshop/6-2_infomaterial_zum_downloaden/Infoblaetter_zu_gewalt/Factsheet_Femizide-in-Oesterreich_AOeF.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- FRA—European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey; FRA: Vienna, Austria, 2014; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Wasson, J.H.; Jette, A.M.; Anderson, J.; Johnson, D.J.; Nelson, E.C.; Kilo, C.M. Routine, single-item screening to identify abusive relationships in women. J. Fam. Pract. 2000, 49, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar]

| Injury Type | PRE | COVID-19 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| contusion, distortion | 211 (85.1%) | 162 (83.9%) | 0.742 |

| lacerating wounds | 23 (9.3%) | 30 (15.5%) | 0.045 * |

| cuts, stab wounds | 12 (4.8%) | 5 (2.6%) | 0.224 |

| fractures, tooth lesions, dislocation | 29 (11.7%) | 28 (14.5%) | 0.382 |

| hematomas | 22 (8.9%) | 24 (12.4%) | 0.224 |

| abrasions, degloving | 33 (13.3%) | 28 (14.5%) | 0.717 |

| concussion | 6 (2.4%) | 5 (2.6%) | >0.999 |

| intracerebral bleeding | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | >0.999 |

| bite wounds | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.635 |

| internal organ injuries | 0 | 2 (1.0%) | 0.191 |

| burns | 0 | 1 (0.5%) | 0.438 |

| Trauma Mechanism | PRE | COVID-19 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| punching, kicking, pushing | 227 (91.5%) | 172 (89.1%) | 0.392 |

| blunt weapon | 13 (5.2%) | 13 (6.7%) | 0.509 |

| sharp weapon | 11 (4.4%) | 5 (2.6%) | 0.304 |

| strangling | 6 (2.4%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0.475 |

| biting | 2 (0.8%) | 2 (1.0%) | >0.999 |

| burning | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | >0.999 |

| injury in context of a sexual violation | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | >0.999 |

| no specified modality | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.5%) | >0.999 |

| Citizenship (Region) | PRE (n = 248) | COVID-19 (n = 193) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 127 (51.2%) | 117 (60.6%) | 0.016 * |

| Eastern Europe | 69 (27.8%) | 40 (20.7%) | |

| Southern Europe | 7 (2.8%) | 4 (2.1%) | |

| other European countries | 8 (3.2%) | 2 (1.0%) | |

| Africa | 7 (2.8%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Asia | 8 (3.2%) | 6 (3.1%) | |

| America | 0 | 5 (2.6%) | |

| Middle eastern countries | 18 (7.3%) | 15 (7.8%) | |

| stateless | 4 (1.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| not specified | 0 | 2 (1.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Babeluk, R.; Maier, B.; Bach, T.; Hajdu, S.; Jaindl, M.; Antoni, A. The Hidden Pandemic: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Trauma Cases Due to Domestic Violence Admitted to the Biggest Level-One Trauma Center in Austria. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13010246

Babeluk R, Maier B, Bach T, Hajdu S, Jaindl M, Antoni A. The Hidden Pandemic: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Trauma Cases Due to Domestic Violence Admitted to the Biggest Level-One Trauma Center in Austria. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(1):246. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13010246

Chicago/Turabian StyleBabeluk, Rita, Bernhard Maier, Timothée Bach, Stefan Hajdu, Manuela Jaindl, and Anna Antoni. 2024. "The Hidden Pandemic: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Trauma Cases Due to Domestic Violence Admitted to the Biggest Level-One Trauma Center in Austria" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 1: 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13010246

APA StyleBabeluk, R., Maier, B., Bach, T., Hajdu, S., Jaindl, M., & Antoni, A. (2024). The Hidden Pandemic: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Trauma Cases Due to Domestic Violence Admitted to the Biggest Level-One Trauma Center in Austria. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(1), 246. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13010246