Behavioral Interventions on Periodontitis Patients to Improve Oral Hygiene: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

- Participants: Adult patients aged 18 or over with periodontitis, excluding patients who only had gingivitis, patients with comorbidities affecting periodontal status (e.g., diabetes mellitus), or patients with orthodontic appliances.

- Interventions: OH instructional strategies and behavioral or educational interventions provided by oral health professionals and/or psychologists/counselors to increase adherence to OH advice.

- Comparison: No OH instructions (OHI) or regular OHI provided by oral health specialists.

- Outcome measures: Any established index for measuring the amount of plaque and inflammation (bleeding before and after the intervention).

- Study design: RCTs, NRCTs, cohort studies, and case-control studies with a follow-up of at least 1 month.

2.4. Data Collection

- Periodontal status, age, and sample size;

- Study design;

- Type of intervention;

- Follow-up period;

- Measures of periodontal status;

- Impact of interventions on periodontal status.

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Synthesis of the Results

3. Results

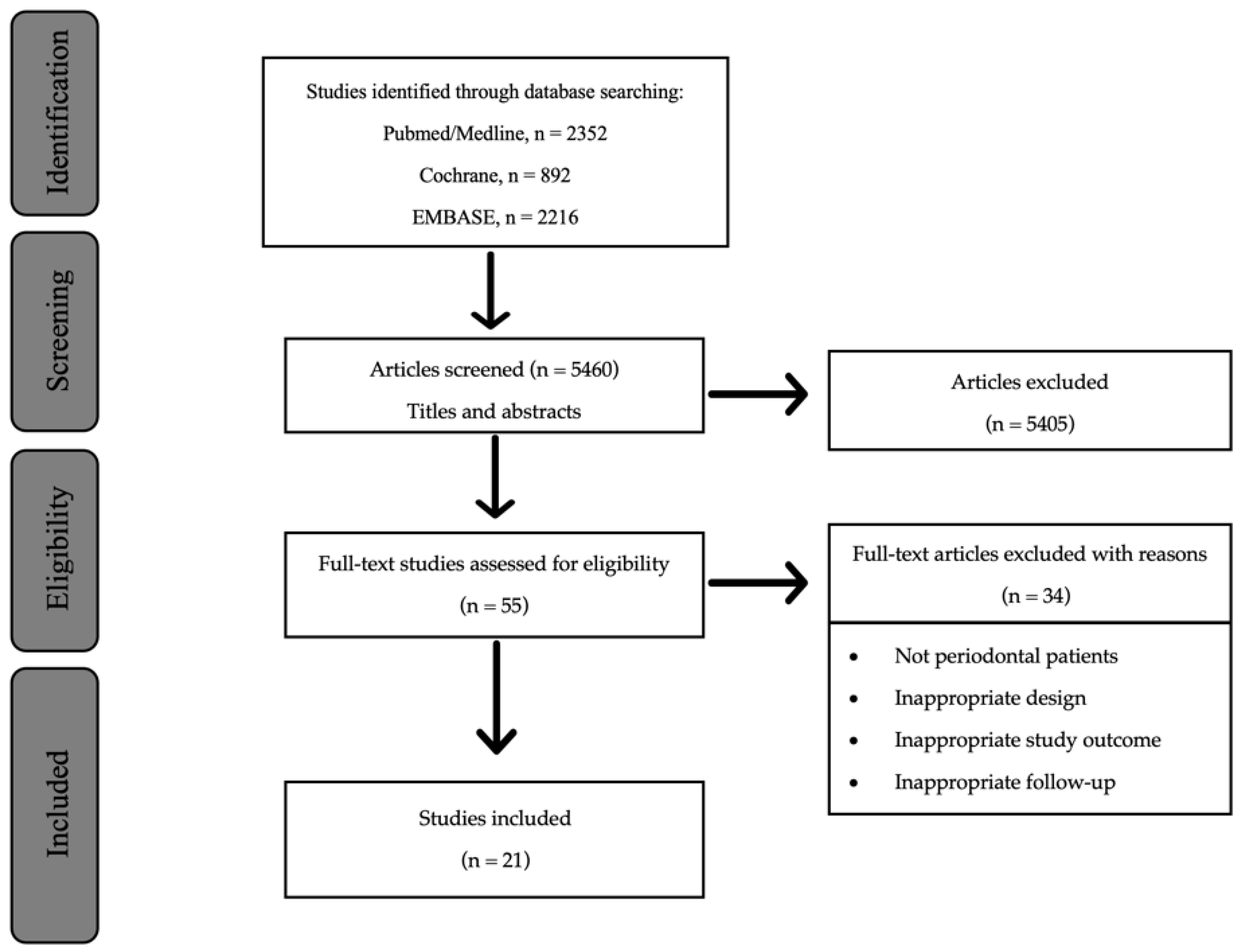

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias of the Included Studies

3.4. Impact of the Different Strategies Based on Audio-Visual Tools for OHI

3.5. Impact of the Psychological Models of Health-Related Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OH | oral hygiene |

| BoP | bleeding on probing |

| SPT | supportive periodontal therapy |

| SCMs | social cognition models |

| CBT | cognitive behavioral therapy |

| MI | motivational interviewing |

| PICOS | patient, intervention, control, outcome, and study design |

| RCTs | randomized controlled clinical trials |

| NRCTs | non-randomized controlled clinical trials |

| CI | confidence intervals |

| OR | odds ratio |

| NR | not reported |

| T | test |

| C | control |

| OHI | oral hygiene instructions |

| PPD | probing pocket depth |

| PD | pocket depth |

| PI | plaque index |

| PS | plaque score |

| FMPS | full mouth plaque score |

| GI | gingival index |

| GB | gingival bleeding |

| BI | bleeding index |

| BOMP | bleeding on marginal probing |

| CAL | clinical attachment level |

| CSCCM | client self-care commitment model |

References

- Petersen, P.E.; Ogawa, H. Strengthening the Prevention of Periodontal Disease: The WHO Approach. J. Periodontol. 2005, 76, 2187–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.P.; Schätzle, M.A.; Löe, H. Gingivitis as a risk factor in periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, N.P.; Joss, A.; Orsanic, T.; Gusberti, F.A.; Siegrist, B.E. Bleeding on probing. A predictor for the progression of periodontal disease? J Clin. Periodontol. 1986, 13, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramseier, C.A. Potential impact of subject-based risk factor control on periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T.; Taylor, S.E. Social Cognition: From Brains to Culture; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, H.; Diefenbach, M.; Leventhal, E.A. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1992, 16, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P. (Eds.) Predicting and Changing Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models, 3rd ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Why People Use Health Services. Milbank Mem. Fund Q. 1966, 44, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R. Modeling Health Behavior Change: How to Predict and Modify the Adoption and Maintenance of Health Behaviors. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T. Thinking and Depression: II. Theory and Therapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1964, 10, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, K.; Byrne, M. The key principles of cognitive behavioural therapy. InnovAiT Educ. Inspir. Gen. Pract. 2013, 6, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed. J. Healthc. Qual. 2003, 25, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catley, D.; Goggin, K.; Harris, K.J.; Richter, K.P.; Williams, K.; Patten, C.; Resnicow, K.; Ellerbeck, E.F.; Bradley-Ewing, A.; Lee, H.S.; et al. A Randomized Trial of Motivational Interviewing: Cessation Induction Among Smokers With Low Desire to Quit. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg-Smith, S.M.; Stevens, V.J.; Brown, K.M.; Van Horn, L.; Gernhofer, N.; Peters, E.; Greenberg, R.; Snetselaar, L.; Ahrens, L.; Smith, K. A brief motivational intervention to improve dietary adherence in adolescents. Health Educ. Res. 1999, 14, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, K.; Bayley, A.; Twist, K.; Stewart, K.; Ridge, K.; Britneff, E.; Greenough, A.; Ashworth, M.; Rundle, J.; Cook, D.; et al. Reducing weight and increasing physical activity in people at high risk of cardiovascular disease: A randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of enhanced motivational interviewing intervention with usual care. Heart 2019, 106, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Martel, D.; Boronat, M.; Alberiche-Ruano M del, P.; Algara-González, M.A.; Ramallo-Fariña, Y.; Wägner, A.M. Motivational Interviewing and Self-Care in Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Study Protocol. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 574312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, V.-C.; Goossens, M.E.J.B.; A Verbunt, J.; Köke, A.J.; Smeets, R.J.E.M. Effects of nurseled motivational interviewing of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain in preparation of rehabilitation treatment (PREPARE) on societal participation, attendance level, and cost-effectiveness: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013, 14, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boman, J.; Lindqvist, H.; Forsberg, L.; Janlert, U.; Granåsen, G.; Nylander, E. Brief manual-based single-session Motivational Interviewing for reducing high-risk sexual behaviour in women—An evaluation. Int. J. STD AIDS 2018, 29, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.T.; Mui, J.H.C.; Cheung, E.F.C.; A Gray, R. Effects of motivational interviewing-based adherence therapy for schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015, 16, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, B.; Abrahamsson, K.H. Overcoming behavioral obstacles to prevent periodontal disease: Behavioral change techniques and self-performed periodontal infection control. Periodontology 2000 2020, 84, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, A.N.P.J.; Newton, J.T. Changing the behavior of patients with periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 2009, 51, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; Hill, K. Getting the message across to periodontitis patients: The role of personalised biofeedback. Int. Dent. J. 2008, 58, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carra, M.C.; Detzen, L.; Kitzmann, J.; Woelber, J.P.; Ramseier, C.A.; Bouchard, P. Promoting behavioural changes to improve oral hygiene in patients with periodontal diseases: A systematic review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, University of Ottawa, Canada. 2009. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Rayant, G.A.; Sheiham, A. An analysis of factors affecting compliance with tooth-cleaning recommendations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1980, 7, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.-J.; Lo, S.-Y.; Kuo, C.-L.; Wang, Y.-L.; Hsiao, H.-C. Development of an intervention tool for precision oral self-care: Personalized and evidence-based practice for patients with periodontal disease. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; Lee, W.R.; Seo, J.-M.; Im, C. Light-Induced Fluorescence-Based Device and Hybrid Mobile App for Oral Hygiene Management at Home: Development and Usability Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojima, M.; Hanioka, T.; Kuboniwa, M.; Nagata, H.; Shizukuishi, S. Development of Web-based intervention system for periodontal health: A pilot study in the workplace. Med. Inform. Internet Med. 2003, 28, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, G.; Spanier, A.B. Developing a Mobile App (iGAM) to Promote Gingival Health by Professional Monitoring of Dental Selfies: User-Centered Design Approach. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e19433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, L.A.; Keffer, M.A.; Fleck-Kandath, C. Self-efficacy, reasoned action, and oral health behavior reports: A social cognitive approach to compliance. J. Behav. Med. 1991, 14, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, L.A.; Keffer, M.A.; Davis, E.L.; Christersson, L.A. Self-efficacy and reasoned action: Predicting oral health status and behaviour at one, three, and six month intervals. Psychol. Health 1993, 8, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, B.; Öhrn, K.; Oscarson, N.; Lindberg, P. An individually tailored treatment programme for improved oral hygiene: Introduction of a new course of action in health education for patients with periodontitis. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2009, 7, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühner, M.K.; Raetzke, P.B. The Effect of Health Beliefs on the Compliance of Periodontal Patients with Oral Hygiene Instructions. J. Periodontol. 1989, 60, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schensul, J.; Reisine, S.; Salvi, A.; Ha, T.; Grady, J.; Li, J. Evaluating mechanisms of change in an oral hygiene improvement trial with older adults. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenthöfer, A.; Dieke, R.; Dieke, A.; Wege, K.-C.; Rammelsberg, P.; Hassel, A.J. Improving oral hygiene in the long-term care of the elderly—A RCT. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelber, J.P.; Bienas, H.; Fabry, G.; Silbernagel, W.; Giesler, M.; Tennert, C.; Stampf, S.; Ratka-Krüger, P.; Hellwig, E. Oral hygiene-related self-efficacy as a predictor of oral hygiene behaviour: A prospective cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, C.R.; Clarkson, J.E.; Duncan, A.; Lamont, T.J.; Heasman, P.A.; Boyers, D.; Goulão, B.; Bonetti, D.; Bruce, R.; Gouick, J.; et al. Improving the Quality of Dentistry (IQuaD): A cluster factorial randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness and cost–benefit of oral hygiene advice and/or periodontal instrumentation with routine care for the prevention and management of periodontal disease in dentate adults attending dental primary care. Health Technol. Assess. 2018, 22, 1–144. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, M.R.; Alvarez, M.J.; Godinho, C.A.; Almeida, T.; Pereira, C.R. Self-regulation in oral hygiene behaviours in adults with gingivitis: The mediating role of coping planning and action control. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 18, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T. Role of health beliefs in patient compliance with preventive dental advice. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1994, 22, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ak’hali, M.S.; Halboub, E.S.; Asiri, Y.M.; Asiri, A.Y.; Maqbul, A.A.; Khawaji, M.A. WhatsApp-assisted Oral Health Education and Motivation: A Preliminary Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnacke, D.; Beldoch, M.; Bohn, G.H.; Seghaoui, O.; Hegel, N.; Deinzer, R. Oral and Written Instruction of Oral Hygiene: A Randomized Trial. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deinzer, R.; Harnacke, D.; Mengel, R.; Telzer, M.; Lotzmann, U.; Wöstmann, B. Effectiveness of Computer-Based Training on Toothbrush Skills of Patients Treated With Crowns: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garyga, V.; Pochelu, F.; Thivichon-Prince, B.; Aouini, W.; Santamaria, J.; Lambert, F.; Maucort-Boulch, D.; Gueyffier, F.; Gritsch, K.; Grosgogeat, B. GoPerio—Impact of a personalized video and an automated two-way text-messaging system in oral hygiene motivation: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019, 20, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shida, H.; Okabayashi, S.; Yoshioka, M.; Takase, N.; Nishiura, M.; Okazawa, Y.; Kiyohara, K.; Konda, M.; Nishioka, N.; Kawamura, T.; et al. Effectiveness of a digital device providing real-time visualized tooth brushing instructions: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, T.; Alyafi, R.; Bantan, N.; Alzahrani, R.; Elfirt, E. Comparison of Effectiveness of Mobile App versus Conventional Educational Lectures on Oral Hygiene Knowledge and Behavior of High School Students in Saudi Arabia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 1901–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshman, Z.; Ainsworth, H.; Chestnutt, I.G.; Day, P.; Dey, D.; El Yousfi, S.; Fairhurst, C.; Gilchrist, F.; Hewitt, C.; Jones, C.; et al. Brushing RemInder 4 Good oral HealTh (BRIGHT) trial: Does an SMS behaviour change programme with a classroom-based session improve the oral health of young people living in deprived areas? A study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2019, 20, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, E.; Shou, L. A randomised controlled trial of a smartphone application for improving oral hygiene. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 226, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.P.; Davies, W.I.R.; Yuen, K.W.; Ma, M.H. Comparison of modes of oral hygiene instruction in improving gingival health. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1996, 23, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.R.; Alvarez, M.J.; Godinho, C.A.; Pereira, C. Psychological, behavioral, and clinical effects of intraoral camera: A randomized control trial on adults with gingivitis. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2016, 44, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.; Alvarez, M.; Godinho, C.A.; Roberto, M.S. An eight-month randomized controlled trial on the use of intraoral cameras and text messages for gingivitis control among adults. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2019, 17, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebolz, D.; Herz, A.; Brunner, E.; Hornecker, E.; Mausberg, R.F. Individual versus group oral hygiene instruction for adults. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2009, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, J.; Ramsay, C.; Lamont, T.; Goulao, B.; Worthington, H.; Heasman, P.; Norrie, J.; Boyers, D.; Duncan, A.; van der Pol, M.; et al. Examining the impact of oral hygiene advice and/or scale and polish on periodontal disease: The IQuaD cluster factorial randomised controlled trial. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 230, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, J.E.; Ramsay, C.R.; Averley, P.; Bonetti, D.; Boyers, D.; Campbell, L.; Chadwick, G.R.; Duncan, A.; Elders, A.; Gouick, J.; et al. IQuaD dental trial; improving the quality of dentistry: A multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing oral hygiene advice and periodontal instrumentation for the prevention and management of periodontal disease in dentate adults attending dental primary care. BMC Oral Health 2013, 13, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.E.; Wolfe, G.R.; Maeder, L.; Hartz, G.W. Changes in dental knowledge and self-efficacy scores following interventions to change oral hygiene behavior. Patient Educ. Couns. 1996, 27, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaedicke, K.M.; Bissett, S.M.; Finch, T.; Thornton, J.; Preshaw, P.M. Exploring changes in oral hygiene behaviour in patients with diabetes and periodontal disease: A feasibility study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2018, 17, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, A.; Watts, T.L.P.; Newton, J.T. Health control beliefs and quality of life considerations before and during periodontal treatment. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2007, 5, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.-H.; Huang, Y.-K.; Lin, K.-D.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Huang, W.-F.; Huang, H.-L. Randomized Controlled Trial on Effects of a Brief Clinical-Based Intervention Involving Planning Strategy on Self-Care Behaviors in Periodontal Patients in Dental Practice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakudate, N.; Morita, M.; Sugai, M.; Kawanami, M. Systematic cognitive behavioral approach for oral hygiene instruction: A short-term study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.A.; Mithani, S.; Sadeghi, G.; Palomo, L. Effectiveness of Oral Hygiene Instructions Given in Computer-Assisted Format versus a Self-Care Instructor. Dent. J. 2018, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.J.; Hollis, J.F.; Stevens, V.J.; Mount, K.; Mullooly, J.P.; Johnson, B.D. Effective group behavioral intervention for older periodontal patients. J. Periodontal Res. 1997, 32, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, R.; Tosolin, F.; Ghilardi, L.; Zanardelli, E. Psychological intervention in patients with poor compliance. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1996, 23, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baab, D.; Weinstein, P. Longitudinal evaluation of a self-inspection plaque index in periodontal recall patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1986, 13, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenman, J.; Lundgren, J.; Wennström, J.L.; Ericsson, J.S.; Abrahamsson, K.H. A single session of motivational interviewing as an additive means to improve adherence in periodontal infection control: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenman, J.; Wennström, J.; Abrahamsson, K. A brief motivational interviewing as an adjunct to periodontal therapy—A potential tool to reduce relapse in oral hygiene behaviours. A three-year study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2018, 16, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, V.S.; Bray, K.K.; MacNeill, S.; Catley, D.; Williams, K. Impact of single-session motivational interviewing on clinical outcomes following periodontal maintenance therapy. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2012, 11, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woelber, J.P.; Spann-Aloge, N.; Hanna, G.; Fabry, G.; Frick, K.; Brueck, R.; Jähne, A.; Vach, K.; Ratka-Krüger, P. Training of Dental Professionals in Motivational Interviewing can Heighten Interdental Cleaning Self-Efficacy in Periodontal Patients. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, A.; Dufour, T.; Jeanne, S. Application of self-regulation theory and motivational interview for improving oral hygiene: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, P.; Lenoir, N.; D’Hoore, W.; Bercy, P. Improving patients’ compliance with the treatment of periodontitis: A controlled study of behavioural intervention. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcouffe, F. Improvement of oral hygiene habits: A psychological approach 2-year data. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1988, 15, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, B.; Lindberg, P.; Oscarson, N.; Öhrn, K. Improved compliance and self-care in patients with periodontitis—A randomized control trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2006, 4, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, B.; Öhrn, K.; Oscarson, N.; Lindberg, P. The effectiveness of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on oral hygiene behaviour in patients with periodontal disease: A blinded randomized-controlled clinical trial (one-year follow-up): Individually tailored oral hygiene treatment. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jönsson, B.; Öhrn, K.; Lindberg, P.; Oscarson, N. Evaluation of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on periodontal health: Individually tailored treatment. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2010, 37, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asimakopoulou, K.; Nolan, M.; McCarthy, C.; Newton, J.T. The effect of risk communication on periodontal treatment outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.R.; Psych, M.; Alvarez, M.J.; Godinho, C.A. The Effect of Mobile Text Messages and a Novel Floss Holder on Gingival Health: A randomized control trial. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 94, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Glavind, L.; Zeuner, E. Evaluation of a television-tape demonstration for the reinforcement of oral hygiene instruction. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1986, 13, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavind, L.; Zeuner, E.; Attström, R. Oral hygiene instruction of adults by means of a self-instructional manual. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1981, 8, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavind, L.; Zeuner, E.; Attström, R.; Attströum, R. Evaluation of various feedback mechanisms in relation to compliance by adult patients with oral home care instructions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1983, 10, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavind, L.; Zeuner, E.; Attsträm, R. Oral cleanliness and gingival health following oral hygiene instruction by selfed-educational programs. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1984, 11, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, B.; Baker, S.R.; Lindberg, P.; Oscarson, N.; Öhrn, K. Factors influencing oral hygiene behaviour and gingival outcomes 3 and 12 months after initial periodontal treatment: An exploratory test of an extended Theory of Reasoned Action. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.T.; Asimakopoulou, K. Managing oral hygiene as a risk factor for periodontal disease: A systematic review of psychological approaches to behaviour change for improved plaque control in periodontal management. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S36–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Eickholz, P.; Loos, B.G.; Papapanou, P.; van der Velden, U.; Armitage, G.; Bouchard, P.; Deinzer, R.; Dietrich, T.; Hughes, F.; et al. Principles in prevention of periodontal diseases: Consensus report of group 1 of the 11 th European Workshop on Periodontology on effective prevention of periodontal and periimplant diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S5–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, T.; Stead, L.; Silagy, C. Effectiveness of interventions to help people stop smoking: Findings from the Cochrane Library. BMJ 2000, 321, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fekete, E.M.; Antoni, M.H.; Schneiderman, N. Psychosocial and behavioral interventions for chronic medical conditions. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2007, 20, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldsoe, B.S.; Marshall, A.L.; Miller, Y.D. Behavior Change Interventions Delivered by Mobile Telephone Short-Message Service. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.; Maturana, C.; Coloma, S.; Carrasco-Labra, A.; Giacaman, R. Teledentistry and mHealth for Promotion and Prevention of Oral Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Michie, S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Periodontal Status Age (Year) Sample Size | Study Design | Intervention | Follow-Up | Outcome Assessed | Impact on Plaque Score {Mean (SD)} or {Percentage %} | Impact on Bleeding Score {Mean (SD)} or {Percentage %} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUDIO-VISUAL POWERPOINT | |||||||

| Williams et al. 2018 [65] | Mild to moderate periodontitis (PD < 6 mm) 21–80 years n = 58 T group n = 30 C group n = 28 | RCT | Same OHI delivered: Test: Computer-teaching format (8 min audio-visual PowerPoint presentation containing 12 slides). Control: Self-care instructor (8 min). | Baseline (T0) 4 weeks (T1) | 6 tooth surfaces: PS (O’Leary) BI (Silness and Loe) BoP% | TEST Baseline: 68 ± 10.7 At 4 weeks: 79.8 ± 11.4 CONTROL Baseline: 65.8 ± 7.1 At 4 weeks: 76.5 ± 11.9 | TEST Baseline: 0.28 ± 0.1 42% ± 15.3 At 4 weeks: 0.23 ± 0.09 32.2% ± 20.9 CONTROL Baseline: 0.26 ± 0.1 37.8% ± 15.2 At 4 weeks: 0.17 ± 0.1 30.6% ± 10.7 |

| VIDEOTAPE | |||||||

| Glavind et al., 1986 [81] | Few periodontal pockets > 5 mm 32–63 years n = 24 T group n = 12 C group n = 12 | NRCT | Both groups: OHI. Test: Reinforcement of the OHI by videotape (12 min) at the 3-week follow-up. | Baseline (T0) 2 weeks (T1) 3 weeks (T2) 8 weeks (T3) | 4 tooth surfaces: PI%: (presence/ absence) BI%: (presence/ absence) | TEST Baseline: 62% (16.8) At 2 weeks: 59% (16.7) At 3 weeks: 29% (19.5) At 8 weeks: 28% (16.3) CONTROL Baseline: 58% (16.2) At 2 weeks: 52% (18.4) At 3 weeks: 23% (19.0) At 8 weeks: 22% (12.5) | TEST Baseline: 51% (19.8) At 8 weeks: 29% (17.0) CONTROL Baseline: 45% (14.8) At 8 weeks: 24% (14.8) |

| Reference | Strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Williams et al., 2018 [65] | OHI given in a computer-assisted format (PowerPoint presentation). | No statistically significant difference between the groups. PLAQUE: Significant differences between older and younger participants (<50 years old) trained on the computer. Younger sample was significantly better using the computer format. |

| Glavind et al., 1986 [81] | Reinforcement of the OHI by showing a television tape. | No statistically significant difference between the groups. |

| Reference | Periodontal Status Age (Year) Sample Size | Study Design | Intervention | Follow-Up | Outcome Assessed | Impact on Plaque Score {Mean (SD)} or {Percentage %} | Impact on Bleeding Score {Mean (SD)} or {Percentage %} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOCIAL COGNITIVE THEORY | |||||||

| Little et al., 1997 [66] | Mild to moderate periodontal disease (at least 6 sites PD 4–7 mm) 50–70 years n = 107 T group: n = 54 C group: n = 53 | RCT | Test: 5 weekly, 90-min sessions: skill training, self-monitoring, and feedback Control: Usual periodontal maintenance care | Baseline (T0) 4 months (T1) | 4 tooth surfaces: PI (O’Leary) GI BoP (%) PPD CAL | TEST Baseline: 82% At 4 months: 76% CONTROL Baseline: 80% At 4 months: 80% | TEST Baseline: 24% At 4 months: 15% CONTROL Baseline: 26% At 4 months: 21% |

| Weinstein et al., 1996 [67] | Periodontitis patients 32–50 years n = 20 Control group 1: n = 5 Control group 2: n = 5 Test group 1: n = 5 Test group 2: n = 5 | RCT | Control 1: Bass technique Control 2: Bass technique + 2× weekly verbal feedback Test 1: Bass technique + 2× weekly verbal feedback + positive reinforcement Test 2: Bass technique + 2× weekly verbal feedback + positive reinforcement + Self-monitoring | Baseline (T0) 1 month (T1) 2 months (T2) | FMPS (O’Leary) | CONTROL 1 Baseline: 0.397 (0.165) At 1 month: 0.390 (0.175) At 2 months: 0.384 (0.159) CONTROL 2 Baseline: 0.395 (0.086) At 1 month: 0.271 (0.096) At 2 months: 0.323 (0.079) TEST 1 Baseline: 0.353 (0.187) At 1 month: 0.205 (0.091) At 2 months: 0.228 (0.075) TEST 2 Baseline: 0.376 (0.058) At 1 month: 0.121 (0.017) At 2 months: 0.148 (0.034) | NR |

| Baab et al., 1986 [68] | Periodontitis patients who had completed active periodontal treatment 30–76 years, n = 31 T group n = 15 C group n = 16 | RCT | Both groups: OHI. Test: oral self-inspection manual | Baseline (T0) 2 weeks (T1) 1.5 months (T2) 3 months (T3) 6 months (T4) | 6 tooth surfaces: Plaque% (O’Leary) Gingival bleeding% | Outcomes of measurements are not described numerically | Outcomes of measurements are not described numerically |

| Glavind et al., 1981 [82] | Few periodontal pockets > 5 mm 25–64 years, n = 37 Group 1 n = 12 Group 2 n = 13 Group 3 n = 12 | NRCT | Group 1: Written self-instructional manual of OH Group 2: Individualized OHI Group 3: Minimal OHI | Baseline (T0) 1 week (T1) 2 weeks (T2) 6 weeks (T3) 3 months (T4) 6 months (T5) | 4 tooth surfaces: PI%: (presence/ absence) BI%: (presence/ absence) | GROUP 1 Baseline: 66.2 (19.7) At 1 week: 44.1 (17.2) At 2 weeks: 22.3 (18.7) At 6 weeks: 21.5 (20.4) At 3 months: 17.2 (14.2) At 6 months: 20.4 (15.9) GROUP 2 Baseline: 61.4 (19.3) At 1 week: 43.8 (20.3) At 2 weeks: 27.5 (20.9) At 6 weeks: 23.3 (19.1) At 3 months: 25.1 (21.3) At 6 months: 22.1 (19.2) GROUP 3 Baseline: 66.1 (16.7) At 1 week: 48.1 (16.6) At 2 weeks: 25.6 (16.8) At 6 weeks: 26.4 (20.7) At 3 months: 19.6 (12.0) At 6 months: 19.7 (15.9) | GROUP 1 Baseline: 39.5 (24.4) At 6 weeks: 14.1 (15.7) At 3 months: 18.0 (16.3) At 6 months: 13.1 (14.8) GROUP 2 Baseline: 39.6 (26.9) At 6 weeks: 15.2 (17.6) At 3 months: 18.0 (15.2) At 6 months: 13.1 (10.6) GROUP 3 Baseline: 39.6 (20.9) At 6 weeks: 15.0 (13.6) At 3 months: 14.5 (14.9) At 6 months: 15.9 (12.9) |

| Glavind et al., 1983 [83] | Few periodontal pockets > 5 mm 22–67 years, n = 63 Group B: brushing test n = 17 Group O: open scoring n = 14 Group M: minimal feedback n = 17 Group C: control n = 15 | NRCT | Group B: Written self-instructional manual of OH + feedback + “tooth brushing test”. Group O: Written self-instructional manual of OH + feedback Group M: Written self-instructional manual of OH Group C: Minimal OHI | Baseline (T0) 1 week (T1) 2 weeks (T2) 6 weeks (T3) 3 months (T4) 7 months (T5) 13 months (T6) | 4 tooth surfaces: PI%: (presence/ absence) BI%: (presence/ absence) | GROUP B Baseline: 60.9 (19.6) At 1 week: 35.6 (11.9) At 2 weeks: 23.1 (14.8) At 6 weeks: 28.5 (16.3) At 3 months: 26.5 (18.0) At 7 months: 37.5 (14.5) At 13 months: 35.7 (16.4) GROUP O Baseline: 62.8 (17.2) At 1 week: 37.2 (17.5) At 2 weeks: 27.1 (20.3) At 6 weeks: 27.1 (14.7) At 3 months: 22.4 (18.8) At 7 months: 31.8 (16.6) At 13 months: 30.4 (19.3) GROUP M Baseline: 61.9 (18.3) At 1 week: 36.4 (20.6) At 3 months: 34.4 (21.3) At 7 months: 33.3 (21.0) At 13 months: 29.9 (13.9) GROUP C Baseline: 62.0 (16.8) At 1 week: 34.5 (12.7) At 3 months: 35.3 (12.6) At 7 months: 34.3 (15.6) At 13 months: 37.0 (15.7) | GROUP B Baseline: 49.0 (21.9) At 6 weeks: 29.5 (16.9) At 3 months: 17.2 (14.8) At 7 months: 24.3 (13.5) At 13 months: 24.0 (17.6) GROUP O Baseline: 54.5 (18.3) At 6 weeks: 28.6 (17.3) At 3 months: 13.9 (12.4) At 7 months: 20.9 (15.5) At 13 months: 19.6 (16.4) GROUP M Baseline: 50.3 (16.7) At 6 weeks: 29.8 (14.5) At 3 months: 13.6 (12.1) At 7 months: 22.0 (20.2) At 13 months: 19.9 (13.8) GROUP C Baseline: 53.6 (23.5) At 6 weeks: 30.1 (14.6) At 3 months: 18.8 (11.7) At 7 months: 22.5 (14.4) At 13 months: 34.8 (15.9) |

| Glavind et al., 1984 [84] | Few periodontal pockets > 5 mm 22–67 years, n = 74 Group 1 n = 23 Group 2 n = 27 Group 3 n = 24 | NRCT | Group 1: Self-examination prior to OHI Group 2: OHI Group 3: Delayed OHI (at 6 weeks) | Baseline (T0) 1 week (T1) 2 weeks (T2) 6 weeks (T3) 7 weeks (T4) 3 months (T5) 7 months (T6) | 4 tooth surfaces: PI%: (presence/ absence) BI%: (presence/ absence) | GROUP 1 Baseline: 61.8 (15.7) At 2 weeks: 40.7 (17.4) At 6 weeks: 38.3 (21.0) At 3 months: 31.5 (21.3) At 7 months: 23.7 (16.8) GROUP 2 Baseline 59.4 (17.0) At 2 weeks: 44.3 (17.3) At 6 weeks: 34.3 (16.7) At 3 months: 30.1 (17.2) At 7 months: 23.5 (14.9) GROUP 3 Baseline: 60.3 (16.8) At 6 weeks: 52.0 (17.7) At 7 weeks: 24.5 (13.9) At 3 months: 27.1 (20.3) At 7 months: 19.7 (16.8) | GROUP 1 Baseline: 55.4 (14.4) At 6 weeks: 33.3 (18.5) At 3 months: 17.3 (11.4) At 7 months: 20.4 (11.8) GROUP 2 Baseline: 52.6 (19.2) At 6 weeks: 31.4 (16.8) At 3 months: 19.2 (14.4) At 7 months: 21.9 (13.9) GROUP 3 Baseline: 56.3 (21.2) At 6 weeks: 45.7 (18.9) At 3 months: 21.4 (18.4) At 7 months: 18.0 (17.1) |

| RISK COMMUNICATION, GOAL SETTING, PLANNING, AND SELF-MONITORING | |||||||

| Asimakopoulou et al., 2019 [79] | Periodontitis patients Mean age: 60.61 (11.24) n = 97 T group 1 (RISK) n = 32 T group 2 (GPS) n = 33 C group (TAU) n = 32 | RCT | All groups: OHI T Group 1: 5–10′ explanation of their individualized risk T Group 2: 5–10′ explanation of their individualized risk + setting goals, self-monitoring, and planning | Baseline (T0) 1 month (T1) 3 months (T2) | 4 tooth surfaces: PI% (presence/ absence) 6 tooth surfaces: BoP% (presence/ absence) PPD | TEST 1 (RISK) Baseline: 21.59% (15.49) At 1 month: 12.21% (9.33) At 3 months: 9.87% (7.93) TEST 2 (GPS) Baseline: 16.23% (10.54) At 1 month: 10.91% (9.90) At 3 months: 9.65% (8.06) CONTROL (TAU) Baseline: 13.97% (10.30) At 1 month: 10.87% (7.22) At 3 months: 10.60% (7.66) | TEST 1 (RISK) Baseline: 13.89% (14.88) At 1 month: 5.44% (6.40) At 3 months: 6.72% (7.03) TEST 2 (GPS) Baseline: 9.94% (7.33) At 1 month: 6.11% (7.80) At 3 months: 4.42% (4.23) CONTROL (TAU) Baseline: 8.62% (6.13) At 1 month: 4.37% (3.64) At 3 months: 4.17% (5.51) |

| THEORY OF REASONED ACTION | |||||||

| Jönsson et al., 2012 [85] | Moderate to advanced periodontitis and PI > 0.3 Mean age: T = 52.4 (8.4) C = 50.1 (10.3) n = 113 T group n = 57 C group n = 56 | Data from RCT (Jönsson et al., 2009, 2010) | Questionnaire: Theory of Reasoned Action | Baseline (T0) 3 months (T1) 12 months (T2) | NR | NR | NR |

| TEXT MESSAGES AND HEALTH ACTION PROCESS APPROACH | |||||||

| Araújo et al., 2020 [80] | Periodontal pockets > 3 mm ≥18 years, n = 142 C group (FF) n = 43 T group 1 (NFH) n = 38 T group 2 (TM + NFH) n = 61 | RCT | All groups: HAPA Questionnaire Patient motivation, discussion about treatment needs, goal setting, and individualized OHI (60′) C group: Finger Floss (FF) T group 1: Novel Floss Holder (NFH) T group 2: Novel Floss Holder + Text Messages (TM + NFH) | Baseline (T0) 4 months (T1) | Bleeding on Marginal Probing index (BOMP) | NR | TEST 1 (NFH) Baseline: 1.14 At 4 months: 0.81 TEST 2 (TM + NFH) Baseline: 1.19 At 4 months: 0.62 CONTROL (FF) Baseline: 1.15 At 4 months: 0.82 |

| LEVENTHAL’S SELF-REGULATORY THEORY | |||||||

| Philippot et al., 2005 [74] | Periodontitis patients 20–68 years, n = 30 T group: n = 15 C group: n = 15 | RCT | Both groups: Information and training of self-care T group: Leventhal’s theory Daily records of improvements in periodontal symptoms | Baseline (T0) 1 month (T1) | PI (Silness and Löe) | TEST Baseline: Global 1.63 (0.43) Lingual 1.87 (0.49) Buccal 1.13 (0.55) Proximal 1.83 (0.41) At 1 month: Global 0.24 (0.19) Lingual 0.22 (0.28) Buccal 0.08 (0.08) Proximal 0.43 (0.24) CONTROL Baseline: Global 1.88 (0.41) Lingual 2.03 (0.41) Buccal 1.41 (0.64) Proximal 2.19 (0.40) At 1 month: Global 0.88 (0.38) Lingual 0.84 (0.48) Buccal 0.45 (0.43) Proximal 1.34 (0.55) | NR |

| MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING GUIDED BY LEVENTHAL’S SELF-REGULATORY THEORY | |||||||

| Godard et al., 2011 [73] | Moderate-to- severe chronic periodontitis Mean age: T = 51.6 (16.6) C = 48.3 (16.5) n = 51 T group n = 27 C group n = 24 | RCT | All groups: OHI T group: Single session of MI guided by Leventhal’s theory (15–20′), by 2 experienced periodontists | Baseline (T0) 1 month (T1) | 3 tooth surfaces: PI (O’Leary) | TEST Baseline: Lingual 35% (0.23) Buccal 58% (0.28) Proximal 65% (0.22) At 1 month: Lingual 18% (0.20) Buccal 29% (0.29) Proximal 45% (0.30) CONTROL Baseline: Lingual 37% (0.23) Buccal 59% (0.19) Proximal 68% (0.23) At 1 month: Lingual 27% (0.16) Buccal 43% (0.22) Proximal 73% (0.27) | NR |

| MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING | |||||||

| Stenman et al., 2012 [69] | Moderate chronic periodontitis Mean age: T = 51.9 (8.9) C = 48.9 (12.1) n = 39 T group: n = 19 C group: n = 20 | RCT | All groups: OHI T group: Single session of 20–90′ MI by a psychologist | Baseline (T0) 2 weeks (T1) 4 weeks (T2) 12 weeks (T3) 26 weeks (T4) | 6 tooth surfaces: PI (O’Leary) Marginal gingival bleeding (MBI) (%) | TEST Baseline: 50.2% (21.5) At 3 months: 27.1% (15.2) At 6 months: 25.2% (15.4) CONTROL Baseline: 43.1% (19.2) At 3 months: 19% (13.3) At 6 months: 18.6% (13.2) | TEST Baseline: 36.6% (17.1) At 3 months: 21% (12.5) At 6 months: 18.8% (10.9) CONTROL Baseline: 33% (12.4) At 3 months: 16.2% (13.4) At 6 months: 18.4% (14.1) |

| Stenman et al., 2018 [70] | Moderate chronic periodontitis Mean age: T = 58.3 (10.2) C = 54.2 (10.1) n = 26 T group: n = 13 C group: n = 13 | RCT | All groups: OHI T group: Single session of 20–90′ MI by a psychologist | Baseline (T0) 6 months (T1) 3 years (T2) | 6 tooth surfaces: PI (O’Leary) Marginal gingival bleeding (MBI) (%) | TEST Baseline: 49.6% (23.7) At 6 months: 25.26% (15.3) At 3 years: 42.1% (30.6) CONTROL Baseline: 38.4% (15.3) At 6 months: 15.7% (10.4) At 3 years: 41.9% (30.3) | TEST Baseline: 37.8% (19.7) At 6 months: 17.1% (8.6) At 3 years: 14.7% (9.2) CONTROL Baseline: 32.1% (12.3) At 6 months: 16.3% (8.9) At 3 years: 15.4% (17.6) |

| Brand et al., 2013 [71] | Patients in periodontal maintenance for at least one year and with a BOP ≥ 40% or at least two teeth with interproximal PD ≥ 5 mm Mean age: 61.9 (11.0) n = 56 T group: n = 29 C group: n = 27 | RCT | All groups: Individualized OHI T group: Single brief session of MI (15–20′) by a trained and experienced counselor in MI | Baseline (T0) 6 weeks (T1) 3 months (T2) | 6 tooth surfaces: PI (Quigley–Hein) (Ramfjord teeth) BoP (%) PPD | TEST Baseline: 2.4 (0.6) At 6 weeks: 1.9 (0.6) At 3 months: 2.1 (0.7) CONTROL Baseline: 2.6 (0.5) At 6 weeks: 2.2 (0.4) At 3 months: 2.3 (0.7) | TEST Baseline: 50% (18) At 6 weeks: 31% (14) At 3 months: 33% (15) CONTROL Baseline: 55% (18) At 6 weeks: 40% (19) At 3 months: 36% (20) |

| Woelber et al., 2016 [72] | CPITN ≥ 3 of at least two sextants Mean age: 59.27 (11.40) n = 172 T group: n = 73 C group: n = 99 | RCT | All groups: OHI T group: 4–5 sessions of MI delivered by dental students trained in MI | Baseline (T0) 6 months (T1) | PI (Silness and Löe) GI (Löe and Silness) BoP (%) PPD CAL | TEST Baseline: 0.56 (0.3) At 6 months: 0.72 (0.32) CONTROL Baseline: 0.43 (0.30) At 6 months: 0.54 (0.32) | TEST Baseline: 51.87% (23.18) At 6 months: 46.65% (25.07) CONTROL Baseline: 53.65% (23.86) At 6 months: 51.82% (27.32) |

| COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY | |||||||

| Alcouffe et al., 1988 [75] | Periodontitis patients with no sites of active periodontitis, who did not respond adequately to hygiene instructions (PI > 50%) 29–72 years, n = 26 T group: n = 13 C group: n = 13 | RCT | All groups: 4 teaching sessions of OH T group: Interviewed by a psychologist (50–90′): perception of periodontal disease, notions of recovery, prevention, and personal hygiene measures | Baseline (T0) Every 3 months for 2 years | PI (O’Leary) | TEST Baseline: 68.08 (12.06) At 3 months: 55.31 (13.36) At 6 months: 49.0 (22.58) At 1 year: 50. 64 (20.69) At 2 years: 48.7 (22.32) CONTROL Baseline: 69.38 (10.91) At 3 months: 68.77 (12.21) At 6 months: 67.58 (15.97) At 1 year: 66.55 (18.32) At 2 years: 65.80 (20.60) | NR |

| Jönsson et al., 2006 [76] | Periodontitis patients with insufficient compliance and progress of their periodontal disease Mean age: T = 54.8 (11.7) C = 58.1 (9.9) n = 35 T group n = 19 C group n = 16 | RCT | T group: 4 sessions of Client Self-care Commitment Model (CSCCM) by an experienced dental hygienist C group: 3 sessions of conventional OHI | Baseline (T0) 3 months (T1) | 6 tooth surfaces: PI (Silness and Löe) GI (Löe and Silness) BoP% (4 tooth surfaces) PPD | TEST Baseline: 0.59 (0.17) At 3 months: 0.25 (0.11) CONTROL Baseline: 0.59 (0.29) At 3 months: 0.33 (0.11) | TEST Baseline: 46.8% (13.8) At 3 months: 18.7% (8.3) CONTROL Baseline: 39% (16.0) At 3 months: 16.3% (5.7) |

| COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL THERAPY + MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING | |||||||

| Jönsson et al., 2009 [77] | Moderate to advanced periodontitis and PI > 0.3 Mean age: T = 52.4 (8.4) C = 50.1 (10.3) n = 113 T group n = 57 C group n = 56 | RCT | T group: 5–9 visits of individually tailored oral health educational program based on CBT, using MI, delivered by trained dental hygienist C group: 4–8 visits of OHI One visit lasts 45 to 60 min | Baseline (T0) 3 months (T1) 12 months (T2) | 6 tooth surfaces: PI (Silness and Löe) GI (Löe and Silness) BoP% PPD | TEST Baseline: 0.74 (0.34) At 3 months: 0.17 (0.11) At 12 months: 0.14 (0.13) CONTROL Baseline: 0.73 (0.31) At 3 months: 0.32 (0.22) At 12 months: 0.31 (0.16) | TEST Baseline: 0.92 (0.28) At 3 months: 0.27 (0.14) At 12 months: 0.21 (0.16) CONTROL Baseline: 0.92 (0.23) At 3 months: 0.52 (0.20) At 12 months: 0.50 (0.17) |

| Jönsson et al., 2010 [78] | Moderate to advanced periodontitis and PI > 0.3 Mean age: T = 52.4 (8.4) C = 50.1 (10.3) n = 113 T group n = 57 C group n = 56 | RCT | T group: 5–9 visits of individually tailored oral health educational program based on CBT, using MI, delivered by trained dental hygienist C group: 4–8 visits of OHI One visit lasts 45 to 60 min | Baseline (T0) 3 months (T1) 12 months (T2) | 6 tooth surfaces: PI (Silness and Löe, expressed as % plaque scores ≥ 1) BoP% PPD | TEST Baseline: 59% (18) At 3 months: 17% (10) At 12 months: 14% (12) CONTROL Baseline: 57% (17) At 3 months: 28% (17) At 12 months: 28% (13) | TEST Baseline: 70% (20) At 3 months: 24% (12) At 12 months: 19% (13) CONTROL Baseline: 75% (18) At 3 months: 33% (15) At 12 months: 29% (14) |

| Reference | Strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Little et al., 1997 [66] | 5 weekly, 90-min sessions including skill training, self-monitoring, and feedback. | Test group: Significantly increased their skills and frequency of tooth brushing and flossing. Significant reduction in PI and BoP. Significant relative improvement in PD reduction in PD 3–6 mm. |

| Weinstein et al., 1996 [67] | 2× weekly verbal feedback, positive social reinforcement, and self-monitoring. | Significant motivation of periodontal patients to conduct the OH routine. |

| Baab et al., 1986 [68] | Oral hygiene self-inspection manual. | No statistically significant difference between the groups. |

| Glavind et al., 1981 [82] | Written self-instructional manual of OH and individual OHI. | No statistically significant difference between the groups. |

| Glavind et al., 1983 [83] | Written self-instructional manual of OH, feedback, and “tooth brushing test”. | At 3 months: the “tooth brushing test” and feedback significantly improved plaque scores compared to the other groups. At 13 months: the control group showed a significantly higher gingival bleeding score than the others. |

| Glavind et al., 1984 [84] | Self-examination prior to OHI and delayed OHI. | At 6 weeks, the delayed OHI group showed significantly higher plaque and bleeding scores compared to the other groups. At 3 months, no statistically significant difference between the groups was observed. |

| Asimakopoulou et al., 2019 [79] | 5–10′ explanation of the individualized risk, setting goals, self-monitoring, and planning. | Individualized risk assessment, setting goals, self-monitoring, and planning showed a statistically significant reduction in the percentage of plaque at 1 month and 3 months. Significant improvement in interdental cleaning frequency. |

| Jönsson et al., 2012 [85] | Questionnaire: Theory of Reasoned Action. | Self-efficacy, gender, and cognitive behavioral intervention were important predictors of OH behavioral change. |

| Araújo et al., 2020 [80] | Questionnaire (HAPA). Patient motivation, desired outcomes, treatment needs, goal setting, individualized OHI, and text messages. | The use of text messages significantly improved the clinical measures of BOMP. |

| Philippot et al., 2005 [74] | Leventhal’s theory. Daily records of the improvement in periodontal symptoms. | At the 1-month follow-up, the experimental group showed smaller scores on all indices as compared with the control group. |

| Godard et al., 2011 [73] | Single session of MI guided by Leventhal’s theory (15–20′) by two experienced periodontists introduced to the practice of MI. | The test group showed statistically significant improvement compared to the control group. |

| Stenman et al., 2012 [69] And Stenman et al., 2018 [70] | Single session of MI (20–90′) by a psychologist with extensive experience in MI. | No statistically significant difference between the groups. |

| Brand et al., 2013 [71] | Single brief session of MI (15–20′) by a trained and experienced counselor in MI. | No statistically significant difference between the groups. |

| Woelber et al., 2016 [72] | 4–5 sessions of MI delivered by dental students trained in MI. | No statistically significant difference between the groups in all the clinical parameters. The test group showed significantly higher interdental cleaning self-efficacy than the control group. |

| Alcouffe et al., 1988 [75] | Interviewed by a psychologist (50–90′): assessment of their perception of periodontal disease, recovery, prevention, and personal hygiene measures. | Test group: the majority of the patients improved their PI to below 50% after 1 year. Control group: the majority of patients remained stable or worsened. |

| Jönsson et al., 2006 [76] | 4 sessions of Client Self-care Commitment Model (CSCCM) by an experienced dental hygienist | Test group at 3 months: Statistically significant improvement in PI compared to the control group. Statistically significant increase in the use of interdental cleaning. No statistically significant difference in the reduction in PD > 4 mm between the groups. |

| Jönsson et al., 2009 [77] | 5–9 visits of individually tailored oral health educational program based on CBT, using MI, delivered by a trained dental hygienist. | Statistically significant improvement in PI and GI in the test group between both baseline and 3-month follow-up and baseline and 12-month follow-up compared to the control group. Test group reported a higher frequency of daily inter-dental cleaning. |

| Jönsson et al., 2010 [78] | 5–9 visits of individually tailored oral health educational program based on CBT, using MI, delivered by a trained dental hygienist. | Statistically significant improvement in PI and GI in the test group between both baseline and 3-month follow-up and baseline and 12-month follow-up compared to the control group. No group difference for “pocket closure” and reduction in periodontal pocket depth. More individuals in the test group reached a level of treatment success. |

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | Overall Bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Williams et al. [65] | HIGH | LOW | LOW | LOW | SOME CONCERN | HIGH |

| Little et al. [66] | SOME CONCERN | LOW | LOW | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH |

| Weinstein et al. [67] | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | SOME CONCERN | HIGH |

| Baab et al. [68] | SOME CONCERN | HIGH | LOW | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH |

| Stenman et al. [69] | SOME CONCERN | LOW | LOW | LOW | SOME CONCERN | SOME CONCERN |

| Stenman et al. [70] | HIGH | SOME CONCERN | LOW | LOW | SOME CONCERN | HIGH |

| Brand et al. [71] | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | SOME CONCERN | SOME CONCERN |

| Woelber et al. [72] | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | SOME CONCERN | HIGH | HIGH |

| Godard et al. [73] | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH | SOME CONCERN | HIGH |

| Philippot et al. [74] | SOME CONCERN | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | SOME CONCERN | HIGH |

| Alcouffe et al. [75] | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH |

| Jönsson et al. [76] | HIGH | SOME CONCERN | LOW | LOW | LOW | HIGH |

| Jönsson et al. [77] | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | SOME CONCERN | SOME CONCERN |

| Jönsson et al. [78] | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW | SOME CONCERN | SOME CONCERN |

| Asimakopoulou et al. [79] | HIGH | SOME CONCERN | LOW | HIGH | LOW | HIGH |

| Araújo et al. [80] | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | LOW | SOME CONCERN | HIGH |

| Glavind et al. [82] | Glavind et al. [83] | Glavind et al. [84] | Glavind et al. [81] | Jönsson et al. [85] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newcastle–Ottawa Assessment criteria: | |||||

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | * | * | * | * | * |

| Selection of non-exposed cohort | * | * | * | * | * |

| Ascertainment of exposure | * | ||||

| Demonstration that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study | * | * | * | * | * |

| Comparability of cohorts | * | ||||

| Assessment of outcome | * | * | * | * | * |

| Was follow-up sufficient | * | * | * | * | |

| Adequacy of follow up | * | * | * | * | * |

| TOTAL | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vilar Doceda, M.; Petit, C.; Huck, O. Behavioral Interventions on Periodontitis Patients to Improve Oral Hygiene: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062276

Vilar Doceda M, Petit C, Huck O. Behavioral Interventions on Periodontitis Patients to Improve Oral Hygiene: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(6):2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062276

Chicago/Turabian StyleVilar Doceda, Maria, Catherine Petit, and Olivier Huck. 2023. "Behavioral Interventions on Periodontitis Patients to Improve Oral Hygiene: A Systematic Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 6: 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062276

APA StyleVilar Doceda, M., Petit, C., & Huck, O. (2023). Behavioral Interventions on Periodontitis Patients to Improve Oral Hygiene: A Systematic Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(6), 2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12062276