Risk Factors for Anal Continence Impairment Following a Second Delivery after a First Traumatic Delivery: A Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population

2.2. Objective and Thresholds

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

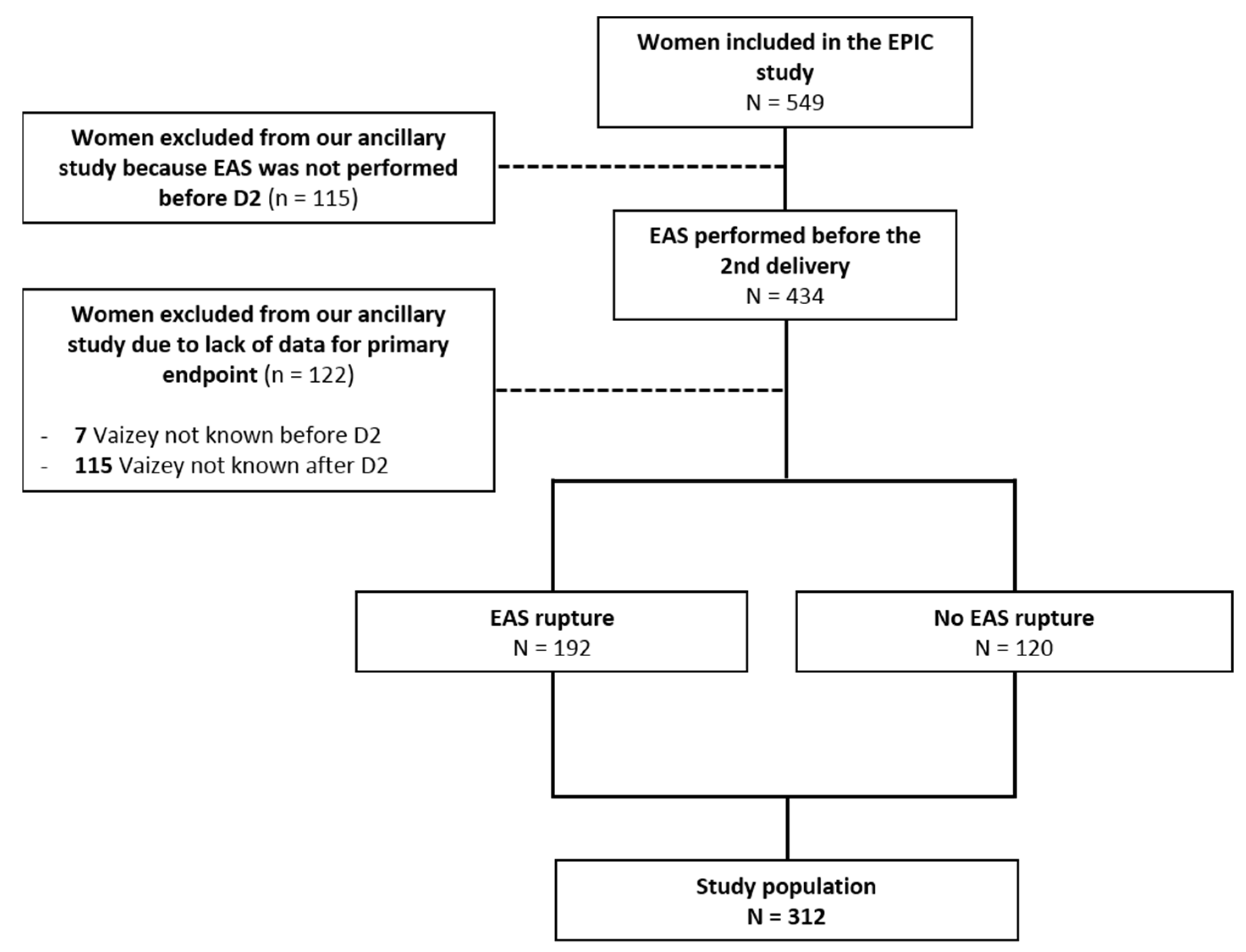

3.1. Participants

3.2. Characteristics of the Deliveries

3.2.1. First Delivery (D1)

3.2.2. Second Delivery (D2)

3.3. Characteristics of Continence

3.4. Risk Factors for Deterioration of Anal Continence 6 Months after D2

3.4.1. Among the 312 Included Patients

3.4.2. Among the 193 Patients That Delivered Vaginally at D2

3.5. Sphincter Tears

3.5.1. Sphincter Tears before D2

3.5.2. Sphincter Tears after D2

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Results

4.2. The Place of EAS

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. What Can Be Offered to a Woman at Risk of Continence Impairment after D2

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Anal incontinence |

| OASI | Obstetrical anal sphincter injury |

| EAS | Endoanal sonography |

| EAS rupture | Sphincter tear diagnosed in EAS |

| D1 | First delivery |

| D2 | Second delivery |

| VD | Vaginal delivery |

| CS | Caesarian section |

| EPIC | Prevention of anal incontinence by Caesarean section |

| MHU | Measure of urinary handicap |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| OR | Odds ratio |

Appendix A. Vaizey Score

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Weekly | Daily | |

| Solid stools incontinence | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Liquid stools incontinence | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Flatus incontinence | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Quality of life impairment | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| No | Yes | ||||

| Need to wear diapers | 0 | 2 | |||

| Use of a constipating treatment | 0 | 2 | |||

| Impossible to delay defecation for more than 15 min | 0 | 4 | |||

| Never: no episode in the last 4 weeks. Rarely: one episode in the last 4 weeks. Sometimes: one or more episode in the last 4 weeks but less than one episode per week. Weekly: one or more episode per week. Daily: one or more episode per day. Vaizey, C.J.; Carapeti, E.; Cahill, J.A.; Kamm, M.A. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 1999, 44, 77–80. | |||||

Appendix B. Starck’s Score

| Defect Characteristics | Score | |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| External sphincter | ||||

| Length of defect | None | Half or less | More than half | Whole |

| Depth of defect | None | Partial | Total | - |

| Size of defect | None | ≤90° | 91–180° | ≥180° |

| Internal sphincter | ||||

| Length of defect | None | Half or less | More than half | Whole |

| Depth of defect | None | Partial | Total | - |

| Size of defect | None | ≤90° | 91–180° | ≥180° |

| No defect = Score 0/Maximal defect = Score 16 | ||||

| Starck, M.; Bohe, M.; Valentin, L. Results of endosonographic imaging of the anal sphincter 2–7 days after primary repair of third- or fourth-degree obstetric sphincter tears. Ultrasound Obs. Gynecol 2003, 22, 609–615. | ||||

Appendix C. Perineal Tears: Classifications of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) and World Health Organization (WHO)

| RCOG and WHO Grades | Anatomical Lesions |

| I | Vaginal epithelium tear |

| II | Tear of the perineal muscles |

| III | Sphincter impairment |

| III-A |

|

| III-B |

|

| III-C |

|

| IV | Breach of the rectal mucosa |

Appendix D. Urinary Handicap Measurement Score (MHU)

| Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Urinary urgency | None | Safety time between 10 and 15 min | Safety time between 5 and 10 min | Safety time between 2 and 5 min | Safety time < 2 min |

| Urinary leakage due to urgency | None | Less than once a month | Several times a month | Several times a week | Several times a day |

| Daytime urination frequency | Urinary interval > 2 h | Voiding interval 1.5 to 2 h | Voiding interval 1 h | Voiding interval half an hour | Voiding interval < half an hour |

| Nocturnal urinary frequency | 0 or 1 miction/night | 2 mictions/night | 3–4 mictions/night | 5–6 mictions/night | >6 mictions/night |

| Stress urinary incontinence | None | During violent efforts (sport, running) | During mild efforts (cough, sneeze, laugh) | During light efforts | Even during change of position |

| Other incontinence | None | Postmictional leaks (>1/month) | Postmictional leaks (1/week) | Postmictional leaks (>1/week) | Postmictional leaks (1/day) |

| Dysuria or Retention | None | Waiting dysuria, terminal dysuria | Abdominal thrusts, chopped miction | Manual thrusts, prolonged urination, residual sensation | Need for a urinary probe |

| Marquis, P.; Amarenco, G.; Sapede, C.; Josserand, F.; McCarthy, C.; Zerbib, M., et al. Elaboration and validation of a specific quality of life questionnaire for urination urgency in women. Prog Urol. 1997, 7, 56–63. | |||||

Appendix E. Description of Sphincter Lesions Revealed in EAS after the First and Second Delivery

| Sphincter Defects before D2 | Total (N = 312) |

| Sphincter tear | 192 (61.5%) |

| Puborectal tear | 0 (0%) |

| Internal sphincter tear (IS) | 18 (5.8%) |

| 0 (0%) |

| 2 (0.6%) |

| 13 (4.2%) |

| 5 (1.6%) |

| Full thickness external sphincter (ES) tear | 103 (33%) |

| Profound ES layer | 175 (56.1%) |

| 5 (1.6%) |

| 123 (39.4%) |

| 166 (53.2%) |

| Superficial ES layer | 120 (38.5%) |

| 2 (0.6%) |

| 110 (35.3%) |

| 116 (37.2%) |

| Sphincter ruptures after D2 | Total (N = 199) |

| Sphincter tear | 143 (71.9%) |

| Puborectal tear | 0 (0%) |

| Internal sphincter tear (IS) | 11 (5.5%) |

| Full thickness external sphincter (ES) rupture | 71 (33.5) |

| Profound ES layer teared | 125 (62.8%) |

| Superficial ES layer teared | 90 (45.2%) |

| “De novo” sphincter rupture | 6 (2.2%) |

| Sphincter defect evidenced in EAS after both deliveries | 133 (66.8%) |

| D2: Second delivery. IS: Internal sphincter. ES: External sphincter. | |

Appendix F. Comparison of the Characteristics of Our Population with those of Women Eligible but Excluded from the Analysis

| Total (N = 312) | NA | Excluded Patients (N = 122) | NA | p | |

| Median age [IQR]. | 33.4 [30.3–35.8] | 0 | 31.1 [27.7–34.2] | 0 | 0.001 |

| Median BMI [IQR] | 26.17 [23.9–29] | 5 | 26.4 [24.4–29.0] | 7 | 0.7 |

| Patients with BMI > 30 | 64 (20.8%) | 5 | 23 (20%) | 7 | 0.6 |

| Transit | |||||

| Constipation and/or Dyschesia | 78 (25%) | 8 | 22 (19%) | 7 | 0.2 |

| Diarrhea | 8 (2.6%) | 8 | 0 (0%) | 7 | 0.1 |

| Normal transit | 211 (69.4%) | 8 | 82 (71%) | 7 | 0.8 |

| Geographical origin | 5 | 3 | |||

| Asia | 12 (3.9%) | 5 (4.2%) | 0.001 | ||

| Europe | 202 (65.8%) | 50 (42%) | |||

| Maghreb | 57 (18.6%) | 42 (35%) | |||

| Other | 36 (11.7%) | 22 (18%) | |||

| Characteristics of D1 | |||||

| Median gestational age in weeks [IQR] | 40 [39–41] | 5 | 40 [39–41] | 5 | 0.3 |

| Use of forceps | 285 (92.2%) | 3 | 106 (90%) | 4 | 0.5 |

| Episiotomy | 266 (86.9%) | 6 | 98 (85%) | 7 | 0.8 |

| Macrosomia | 18 (5.8%) | 4 | 11 (9.3%) | 4 | 0.3 |

| Perineal rehabilitation performed | 225 (74.3%) | 9 | 67 (60%) | 10 | 0.006 |

| Perineal tear | 95 (30.7%) | 7 | 45 (38%) | 8 | 0.6 |

| 27 (8.9%) | 11 (26%) | |||

| 15 (4.9%) | 7 (17%) | |||

| 48 (15.7%) | 22 (52%) | |||

| EAS rupture after D1 | 192 (61.5%) | 0 | 72 (59%) | 0 | 0.3 |

| Hidden rupture after D1 | 146 (47.9%) | 7 | 45 (39%) | 8 | |

| Severe rupture after D1 (Starck ≥ 9) | 18 (5.8%) | 0 | 4 (3.3%) | 0 | 0.5 |

| Continence before D2 | |||||

| Transient anal incontinence | 48 (15.7%) | 7 | 11 (9.5%) | 6 | 0.13 |

| Median Vaizey score before D2 [IQR] | 1 [0–3] | 0 | 0 [0–6] | 4 | 0.9 |

| Median MHU score [IQR] | 4 [2–8] | 16 | 4 [1–8] | 8 | 0.6 |

| Anal incontinence (Vaizey ≥ 5) before D2 | 43 (13.8%) | 0 | 12 (10%) | 4 | 0.4 |

| IQR: Interquartile range. BMI: Body mass index. EAS rupture: Sphincter tear diagnosed in endoanal sonography. NA: Missing data for each characteristic in our main population. p: Significance of the difference in distribution of the variable between the included and excluded population. D1: 1st delivery-D2: 2nd delivery. | |||||

References

- Macmillan, A.K.; Merrie, A.; Marshall, R.; Parry, B.R. The Prevalence of Fecal Incontinence in Community-Dwelling Adults: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Dis. Colon Rectum 2004, 47, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menees, S.B.; Almario, C.V.; Spiegel, B.M.; Chey, W.D. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Fecal Incontinence: Results From a Population-Based Survey. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1672–1681.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damon, H.; Guye, O.; Seigneurin, A.; Long, F.; Sonko, A.; Faucheron, J.-L.; Grandjean, J.-P.; Mellier, G.; Valancogne, G.; Fayard, M.-O.; et al. Prevalence of anal incontinence in adults and impact on quality-of-life. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 2006, 30, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S. Pathophysiology of adult fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, S14–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Bharucha, A.; Dunivan, G.; Goode, P.S.; Lukacz, E.S.; Markland, A.; A Matthews, C.; Mott, L.; Rogers, R.G.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; E Whitehead, W.; et al. Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Classification of Fecal Incontinence: State of the Science Summary for the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Workshop. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faltin, D.L.; Boulvain, M.; Irion, O.; Bretones, S.; Stan, C.; Weil, A. Diagnosis of anal sphincter tears by postpartum endosonography to predict fecal incontinence. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 95, 643–647. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz, L.; Sobhani, I.; Ganansia, R.; Vuagnat, A.; Benifla, J.L.; Darai, E.; Madelenat, P.; Mignon, M. Are sphincter defects the cause of anal incontinence after vaginal delivery? Results of a prospective study. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2000, 43, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, L.; Mandelbrot, L.; Moine, A.B.; Le Tohic, A.; Carnavalet, C.D.C.; Poujade, O.; Roy, C.; Tubach, F. Caesarean section in the second delivery to prevent anal incontinence after asymptomatic obstetric anal sphincter injury: The EPIC multicentre randomised trial. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 128, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, A.H.; Kamm, M.A.; Hudson, C.N.; Thomas, J.M.; Bartram, C.I. Anal-Sphincter Disruption during Vaginal Delivery. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberwalder, M.; Connor, J.; Wexner, S.D. Meta-analysis to determine the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter damage. Br. J. Surg. 2003, 90, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, D.; Kennedy, C.M.; Merrill, D.; Zlatnik, F.J. Risk of Repetition of a Severe Perineal Laceration. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 93, 1021–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edozien, L.; Gurol-Urganci, I.; Cromwell, D.; Adams, E.; Richmond, D.; Mahmood, T.; van der Meulen, J. Impact of third- and fourth-degree perineal tears at first birth on subsequent pregnancy outcomes: A cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 121, 1695–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrar, D.; Tuffnell, D.J.; Ramage, C. Interventions for women in subsequent pregnancies following obstetric anal sphincter injury to reduce the risk of recurrent injury and associated harms. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 11, CD010374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretlove, S.J.; Radley, S.; Toozs-Hobson, P.M.; Thompson, P.J.; Coomarasamy, A.; Khan, K.S. Prevalence of anal incontinence according to age and gender: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2006, 17, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevler, A. The epidemiology of anal incontinence and symptom severity scoring. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2014, 2, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fradet-Menard, C.; Deparis, J.; Gachon, B.; Sichitiu, J.; Pierre, F.; Fritel, X.; Desseauve, D. Obstetrical anal sphincter injuries and symptoms after subsequent deliveries: A 60 patient study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 226, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanger, M.; Lima, S.M.; Cowppli-Bony, A.; Molinié, F.; Terry, M.B. Effects of fertility on breast cancer incidence trends: Comparing France and US. Cancer Causes Control 2021, 32, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fynes, M.; Donnelly, V.; Behan, M.; O’Connell, P.R.; O’Herlihy, C. Effect of second vaginal delivery on anorectal physiology and faecal continence: A prospective study. Lancet 1999, 354, 983–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.; Cassidy, M.; Barassaud, M.L.; Hehir, M.P.; Hanly, A.M.; O’Connell, P.R.; O’Herlihy, C. Does anal sphincter injury preclude subsequent vaginal delivery? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 198, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.A.; Naidu, M.; Thakar, R.; Sultan, A.H. Effect of subsequent vaginal delivery on bowel symptoms and anorectal function in women who sustained a previous obstetric anal sphincter injury. Int. Urogynecology J. 2018, 29, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, I.; Thakar, R.; Sultan, A.H. Mode of delivery after previous obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS)—A reappraisal? Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic. Floor Dysfunct. 2009, 20, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaizey, C.J.; Carapeti, E.; A Cahill, J.; A Kamm, M. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 1999, 44, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S.; Shaw, C.; McGrother, C.; Matthews, R.; Assassa, R.P.; Dallosso, H.; Williams, K.; Brittain, K.; Azam, U.; Clarke, M.; et al. Prevalence of faecal incontinence in adults aged 40 years or more living in the community. Gut 2002, 50, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gommesen, D.; Nohr, E.A.; Qvist, N.; Rasch, V. Obstetric perineal ruptures—Risk of anal incontinence among primiparous women 12 months postpartum: A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 222, 165.e1–165.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, D.; Abramowitz, L.; Castinel, A.; Suduca, J.M.; Staumont, G.; Soudan, D.; Devulder, F.; Pigot, F.; Varastet, M.; Ganansia, R. One-year outcome of haemorrhoidectomy: A prospective multicentre French study. Color. Dis. 2013, 15, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villot, A.; Deffieux, X.; Demoulin, G.; Rivain, A.L.; Trichot, C.; Thubert, T. Management of postpartum anal incontinence: A systematic review. Prog. Urol. 2015, 25, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, G.; Minini, G.; Bernasconi, F.; Perrone, A.; Trezza, G.; Guardabasso, V.; Ettore, G. A prospective study of pelvic floor dysfunctions related to delivery. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 160, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, P.J.; Bartram, C.I. Anal endosonography: Technique and normal anatomy. Abdom. Imaging 1989, 14, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, M.; Bohe, M.; Valentin, L. Results of endosonographic imaging of the anal sphincter 2-7 days after primary repair of third- or fourth-degree obstetric sphincter tears. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 22, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norderval, S.; Markskog, A.; Røssaak, K.; Vonen, B. Correlation between anal sphincter defects and anal incontinence following obstetric sphincter tears: Assessment using scoring systems for sonographic classification of defects. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 31, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquis, P.; Amarenco, G.; Sapède, C.; Josserand, F.; McCarthy, C.; Zerbib, M.; Richard, F.; Jacquetin, B.; Villet, R.; Leriche, B.; et al. Elaboration and validation of a specific quality of life questionnaire for urination urgency in women. Prog. Urol. 1997, 7, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hage-Fransen, M.A.H.; Wiezer, M.; Otto, A.; Wieffer-Platvoet, M.S.; Slotman, M.H.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G.; Pool-Goudzwaard, A.L. Pregnancy- and obstetric-related risk factors for urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, or pelvic organ prolapse later in life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boggs, E.W.; Berger, H.; Urquia, M.; McDermott, C.D. Recurrence of Obstetric Third-Degree and Fourth-Degree Anal Sphincter Injuries. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 124, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangö, H.; Langhoff-Roos, J.; Rosthøj, S.; Saske, A. Long-term anal incontinence after obstetric anal sphincter injury—Does grade of tear matter? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 218, 232.e1–232.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.L.; E Furner, S.; Westercamp, M.; Farquhar, C. Cesarean delivery for the prevention of anal incontinence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 2010, CD006756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, K. Obstetrics and Fecal Incontinence. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2014, 27, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomare, D.F.; De Fazio, M.; Giuliani, R.T.; Catalano, G.; Cuccia, F. Sphincteroplasty for fecal incontinence in the era of sacral nerve modulation. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 5267–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon, H.; Siproudhis, L.; Faucheron, J.-L.; Piche, T.; Abramowitz, L.; Eléouet, M.; Etienney, I.; Godeberge, P.; Valancogne, G.; Denis, A.; et al. Perineal retraining improves conservative treatment for faecal incontinence: A multicentre randomized study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014, 46, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (N = 312) | NA | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age [IQR] | 33.4 [30.3–35.8] | 0 5 5 |

| Median BMI [IQR] | 26.17 [23.9–29] | |

| Patients with BMI > 30 | 64 (20.8%) | |

| Transit at baseline | 8 | |

| Constipation and/or Dyschesia | 78 (25%) | |

| Diarrhea | 8 (2.6%) | |

| Normal transit | 211 (69.4%) | |

| Geographical origin | 5 | |

| Asia | 12 (3.9%) | |

| Europe | 202 (65.8%) | |

| Maghreb | 57 (18.6%) | |

| Other | 36 (11.7%) | |

| First delivery (D1) | ||

| Median gestational age in weeks [IQR] | 40 [39–41] | 5 |

| Use of forceps | 285 (92.2%) | 3 |

| Episiotomy | 266 (86.9%) | 6 |

| Macrosomia | 18 (5.8%) | 4 |

| Obstetrical anal sphincter injury (OASI) | 95 (30.7%) | 3 |

| 27 (8.9%) | |

| 15 (4.9%) | |

| 48 (15.7%) | |

| EAS rupture after D1 | 192 (61.5%) | 0 |

| Hidden rupture after D1 | 146 (47.9%) | 7 |

| Severe rupture after D1 (Starck score ≥ 9) | 18 (5.8%) | 0 |

| Continence at baseline (before D2 visit) | ||

| Perineal rehabilitation performed after D1 | 225 (74.3%) | 9 |

| Median Vaizey score before D2 [IQR] | 1 [0–3] | 0 |

| Transient anal incontinence | 48 (15.7%) | 7 |

| Detailed Vaizey score before D2 | 0 | |

| 135 (43.3%) | |

| 52 (16.7%) | |

| 39 (12.5%) | |

| 22 (7.1%) | |

| 21 (6.7%) | |

| 43 (13.8%) | |

| Median MHU score before D2 [IQR] | 4 [2–8] | 16 |

| Second delivery (D2) | ||

| Median gestational age in weeks [IQR] | 39 [39–40] | 87 |

| Cesarean delivery | 103 (35%) | 16 |

| Vaginal delivery | 193 (65.2%) | 16 |

| Perineal rehabilitation performed after D2 | 201 (69%) | 19 |

| Total (N = 193) | NA | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age [IQR] | 33.3 (30.5, 35.7) | 2 |

| Patients with BMI > 30 | 34 (18%) | |

| Transit at baseline | 4 | |

| Constipation and/or Dyschesia | 51 (27%) | |

| Diarrhea | 5 (2.6%) | |

| Normal transit | 132 (70%) | |

| Geographical origin | 2 | |

| Europe | 125 (65%) | |

| Maghreb | 36 (19%) | |

| Other | 30 (15.7%) | |

| First delivery (D1) | ||

| Median gestational age in weeks [IQR] | 40 [39.0–41.0] | 18 |

| Use of forceps | 177 (93%) | 2 |

| Episiotomy | 167 (88%) | 2 |

| Macrosomia | 12 (6.3%) | 2 |

| Obstetrical anal sphincter injury (OASI) | 49 (26%) | 2 |

| 18 (38%) | 1 |

| 7 (15%) | |

| 23 (48%) | |

| EAS rupture after D1 | 96 (50%) | 3 |

| Hidden rupture after D1 | 79 (42%) | |

| Severe rupture after D1 (Starck score ≥ 9) | 7 (3.6%) | |

| Continence at baseline (before D2 visit) | ||

| Perineal rehabilitation performed after D1 | 145 (77%) | 5 |

| Median Vaizey score before D2 [IQR] | 1 [0–3] | 0 |

| Vaizey ≥ 5 | 25 (13%) | |

| Transient anal incontinence | 31 (16%) | 5 |

| Median MHU score before D2 [IQR] | 5 [2–7] | 10 |

| Second delivery (D2) | ||

| Median gestational age in weeks [IQR] | 40.0 [39.0–40.0] | 79 |

| Macrosomia | 8 (6.1%) | 62 |

| Perineal rehabilitation performed | 130 (71%) | 9 |

| Use of forceps | 13 (6.8%) | 1 |

| Use of vacuum | 12 (6.2%) | 1 |

| Median labor time [IQR] | 4 [2–6] | 68 |

| Episiotomy | 49 (26%) | 2 |

| 2 (4%) 25 (51%) | 22 |

| Obstetrical anal sphincter injury (OASI) | 114 (60%) | 2 |

| 87 (77%) | 1 |

| 24 (21%) | |

| 2 (1.8%) | |

| 0 (0%) | |

| General Population | Total (N = 312) | NA |

|---|---|---|

| Median Vaizey score after D2 [IQR]. | 1 [0–3] | 0 |

| Detailed Vaizey score after D2 | ||

| 137 (43.9%) | |

| 44 (14.1%) | |

| 40 (12.8%) | |

| 23 (7.4%) | |

| 14 (4.5%) | |

| 54 (17.3%) | |

| Vaizey deterioration ≥ 2 points | 67 (21.5%) | |

| Median MHU score after D2 [IQR] | 1 [0–4] | 13 |

| EAS rupture after D2 | 143 (72%) | 113 |

| Women delivering vaginally during the second delivery | Total (N = 193) | NA |

| Median Vaizey score after D2 [IQR]. | 1 [0–3] | 0 |

| Detailed Vaizey score after D2 | ||

| 90 (47%) | |

| 30 (16%) | |

| 23 (12%) | |

| 17 (8.8%) | |

| 9 (4.7%) | |

| 24 (12%) | |

| Vaizey deterioration ≥ 2 points | 34 (18%) | |

| Median MHU score after D2 [IQR] | 1 [0–4] | 9 |

| EAS rupture after D2 | 80 (66%) | 71 |

| “De novo” sphincter rupture † | 6 (3.6%) | 28 |

| Total Population (N = 312) | Cases (N = 67) | OR (95% CI) | p (Wald) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General parameters | |||

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) | 17 | 1.43 (0.76–2.71) | 0.269 |

| Maghreb ethnicity | 14 | 1.24 (0.63–2.44) | 0.533 |

| Transient anal incontinence after D1 (<2 months) | 10 | 0.99 (0.46–2.11) | 0.978 |

| Normal transit before D2 (vs abnormal) (n = 211) | 44 | 0.9 (0.5–1.63) | 0.735 |

| Perineal rehabilitation performed after D1 | 47 | 0.95 (0.51–1.77) | 0.866 |

| Perineal rehabilitation performed after D2 | 40 | 0.92 (0.48–1.75) | 0.789 |

| MHU score before D2 (per point) | 1.06 (0.99–1.12) | 0.098 | |

| MHU score after D2 (per point) | 1.16 (1.07–1.26) | <0.001 | |

| D2 by caesarean section | 30 | 1.92 (1.09–3.38) | 0.023 |

| Anal incontinence (Vaizey ≥ 5) before D2 | 4 | 0.34 (0.12–0.97) | 0.045 |

| Obstetrical parameters related to the 1st delivery | |||

| Macrosomia D1 | 5 | 1.44 (0.5–4.21) | 0.501 |

| Use of forceps D1 | 60 | 0.8 (0.3–2.1) | 0.651 |

| Episiotomy D1 | 54 | 0.59 (0.28–1.24) | 0.168 |

| Analysis of sphincter ruptures | |||

| Sphincter rupture diagnosed in EAS before D2: | |||

| Reference | ||

| 46 | 1.49 (0.84–2.64) | 0.178 |

| Hidden rupture before D2 status: | |||

| 18 | Reference | |

| 34 | 1.57 (0.83–2.96) | 0.164 |

| 14 | 2.13 (0.95–4.74) | 0.065 |

| Severity revealed in EAS before D2: | |||

| 21 | Reference | |

| 42 4 | 1.5 (0.84–2.69) 1.35 (0.4–4.5) | 0.174 0.629 |

| Total Population (N = 312) | OR (95% CI) | p (Wald) |

|---|---|---|

| D2 by cesarean section | 1.56 (0.79–3.08) | 0.201 |

| Anal incontinence (Vaizey ≥ 5) before D2 | 0.27 (0.08–0.86) | 0.027 |

| MHU score after D2 (per point) | 1.22 (1.11–1.33) | <0.001 |

| Hidden rupture (versus no EAS rupture) Grade III-IV OASI (versus no EAS rupture) | 1.26 (0.59–2.72) 2.18 (0.83–5.73) | 0.554 0.113 |

| Population (N = 193) | Cases (N = 34) | OR (95% CI) | p (Wald) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General parameters | |||

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) | 8 | 1.62 (0.6–6.4) | 0.291 |

| Maghreb ethnicity | 8 | 1.49 (0.61–3.64) | 0.386 |

| Transient anal incontinence after D1 (<2 months) | 5 | 0.97 (0.34–2.76) | 0.953 |

| Normal transit before D2 (vs Abnormal) | 21 | 0.79 (0.35–1.77) | 0.569 |

| Perineal rehabilitation performed after D1 | 26 | 1.66 (0.6–4.63) | 0.332 |

| Perineal rehabilitation performed after D2 | 22 | 0.80 (0.36–1.78) | 0.579 |

| MHU score before D2 (per point) | 1.11 (1.01–1.22) | 0.031 | |

| MHU score after D2 (per point) | 1.21 (1.08–1.37) | 0.001 | |

| Anal incontinence (Vaizey ≥ 5) before D2 | 2 | 0.37 (0.08–1.65) | 0.192 |

| Obstetrical parameters related to the 1st delivery | |||

| Macrosomia D1 | 2 | 0.95 (0.2–4.57) | 0.954 |

| Use of forceps D1 | 30 | 0.75 (0.2–2.85) | 0.67 |

| Episiotomy D1 | 27 | 0.51 (0.18–1.43) | 0.203 |

| Analysis of sphincter ruptures | |||

| EAS rupture before D2 | 17 | 1.01 (0.48–2.12) | 0.973 |

| Hidden rupture before D2 status: | |||

| 14 | Ref | |

| 14 | 1.14 (0.51–2.56) | 0.754 |

| 5 | 1.47 (0.47–4.61) | 0.51 |

| Severity revealed in EAS before D2: | |||

| 17 | Ref | |

| 16 | 1.03 (0.49–2.19) | 0.936 |

| 1 | 0.78 (0.09–6.94) | 0.827 |

| EAS rupture after D2: | |||

| 6 | Ref | |

| 2 | 2.25(0.33–15.26) | 0.406 |

| 4 | 1.13 (0.28–4.6) | 0.87 |

| 19 | 0.98 (0.36–2.71) | 0.973 |

| Obstetrical parameters related to the 2nd delivery | |||

| Macrosomia D2 | 1 | 0.59 (0.07–5.02) | 0.628 |

| Instrumental delivery at D2: | |||

| 26 | Ref | |

| 8 | 2.73 (1.06–7.03) | 0.037 |

| Episiotomy D2 (n = 49) | 12 | 1.77 (0.8–3.91) | 0.159 |

| Instrument/Episiotomy combination: | |||

| 20 | Ref | |

| 2 | 1.22 (0.25–6.08) | 0.806 |

| D2 with episiotomy/without instrument | 6 | 1.06 (0.39–2.88) | 0.902 |

| 6 | 5.5 (1.61–18.78) | 0.007 |

| Population (N = 193) | OR (95% CI) | P (Wald) |

|---|---|---|

| Anal incontinence (Vaizey ≥ 5) before D2 | 0.22 (0.04–1.14) | 0.071 |

| MHU score after D2 (per point) | 1.25 (1.1–1.43) | <0.001 |

| Instrument/Episiotomy combination at D2: | ||

| No Instrument and no episiotomy at D2 | Ref | |

| D2 with instruments/without episiotomy | 1.34 (0.26.6.91) | 0.729 |

| D2 with episiotomy/without instrument | 1.03 (0.34.3.12) | 0.953 |

| D2 with instruments and episiotomy | 4.18 (1.05–16.59) | 0.042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marcellier, G.; Dupont, A.; Bourgeois-Moine, A.; Le Tohic, A.; De Carne-Carnavalet, C.; Poujade, O.; Girard, G.; Benbara, A.; Mandelbrot, L.; Abramowitz, L. Risk Factors for Anal Continence Impairment Following a Second Delivery after a First Traumatic Delivery: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041531

Marcellier G, Dupont A, Bourgeois-Moine A, Le Tohic A, De Carne-Carnavalet C, Poujade O, Girard G, Benbara A, Mandelbrot L, Abramowitz L. Risk Factors for Anal Continence Impairment Following a Second Delivery after a First Traumatic Delivery: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(4):1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041531

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcellier, Gabriel, Axelle Dupont, Agnes Bourgeois-Moine, Arnaud Le Tohic, Celine De Carne-Carnavalet, Olivier Poujade, Guillaume Girard, Amélie Benbara, Laurent Mandelbrot, and Laurent Abramowitz. 2023. "Risk Factors for Anal Continence Impairment Following a Second Delivery after a First Traumatic Delivery: A Prospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 4: 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041531

APA StyleMarcellier, G., Dupont, A., Bourgeois-Moine, A., Le Tohic, A., De Carne-Carnavalet, C., Poujade, O., Girard, G., Benbara, A., Mandelbrot, L., & Abramowitz, L. (2023). Risk Factors for Anal Continence Impairment Following a Second Delivery after a First Traumatic Delivery: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(4), 1531. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041531