Safety and Efficacy of Rapid Primary Phacoemulsification on Acute Primary Angle Closure with and without Preoperative IOP-Lowering Medication

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Patients

- Presence of a history of intermittent blurring of vision with halos and at least two of the following symptoms: ocular or periocular pain, nausea and/or vomiting.

- IOP > 30 mmHg and the presence of at least three of the following signs: conjunctival injection, corneal epithelial edema, mid-dilated pupil, shallow anterior chamber, and iris atrophy.

- Completion of more than 1 month of follow-up.

- Secondary glaucoma, such as neovascular glaucoma, phacolytic glaucoma, and uveitic glaucoma.

- Pseudophakic eyes, aphakic eyes, or eyes that underwent LPI.

2.3. Ophthalmic Examinations

2.4. Treatment Protocol

2.5. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Rapid Phacoemulsification

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Operation and Complications

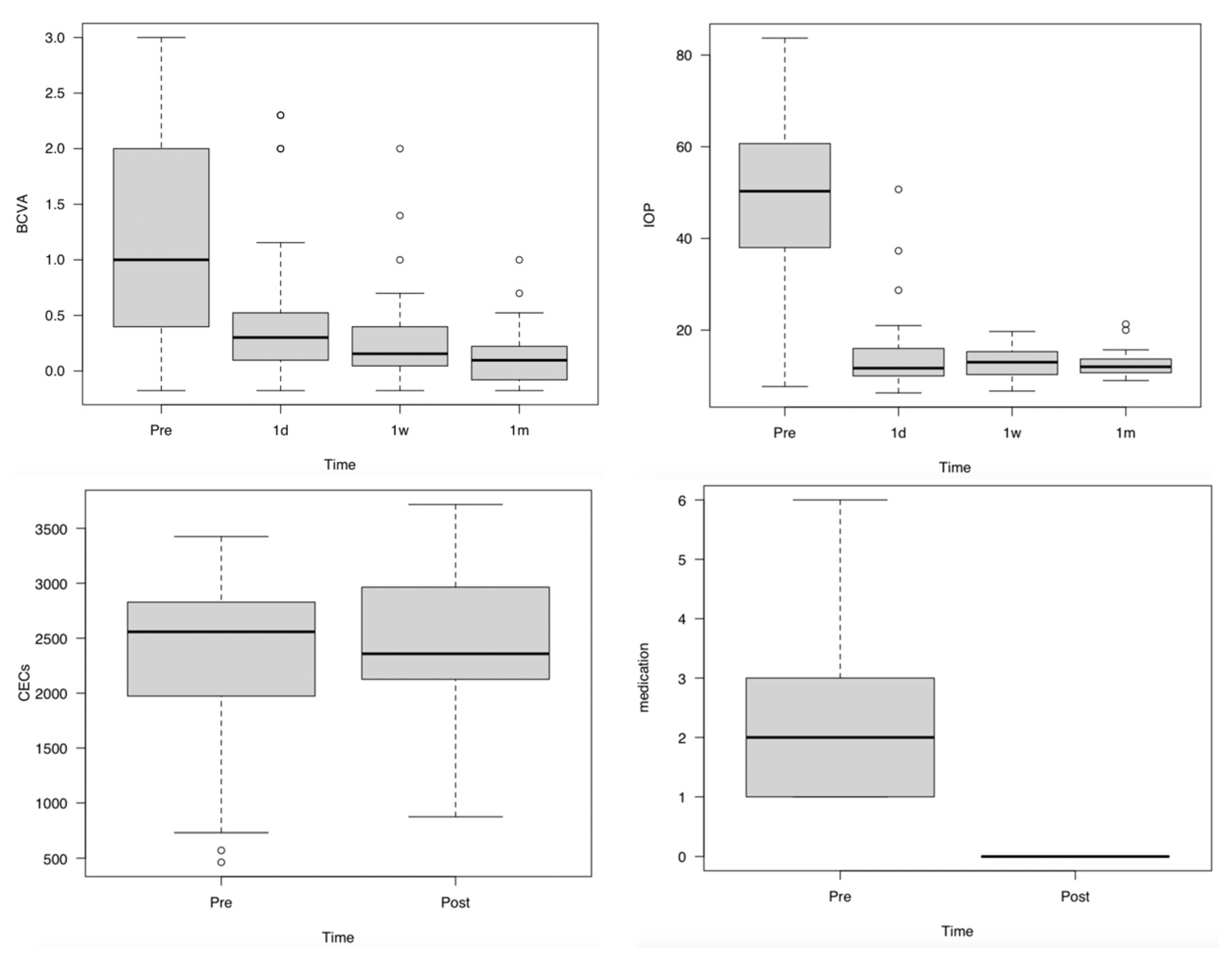

3.3. Changes in BCVA, IOP, and the Number of CECs and IOP-Lowering Medications

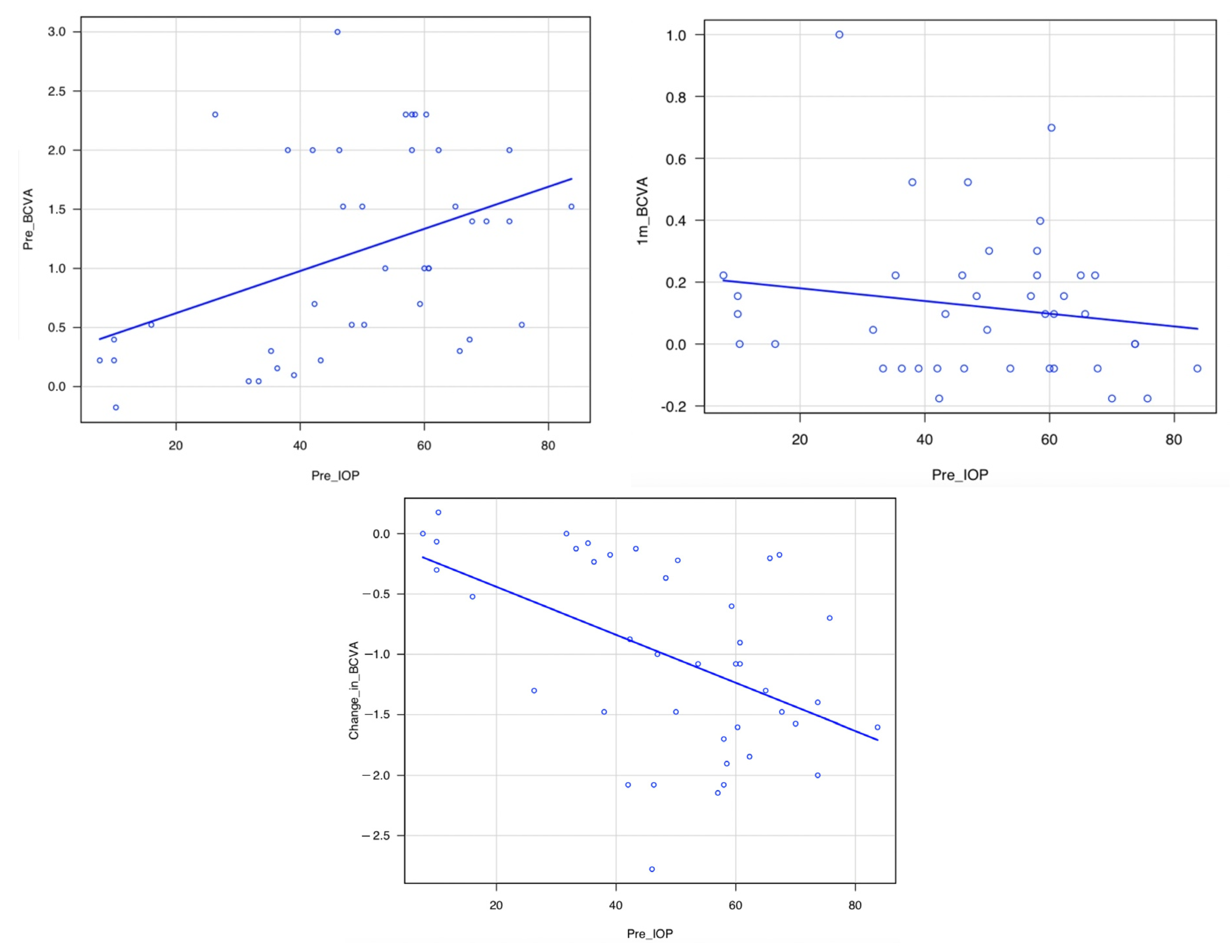

3.4. Correlation between Pre-IOP and Pre-BCVA, Pre-IOP and 1m-BCVA, and Pre-IOP and Change in BCVA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tham, Y.C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, M.J.; Ramke, J.; Marques, A.P.; Bourne, R.R.A.; Congdon, N.; Jones, I.; Ah Tong, B.A.M.; Arunga, S.; Bachani, D.; Bascaran, C.; et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: Vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e489–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobi, P.C.; Dietlein, T.S.; Lüke, C.; Engels, B.; Krieglstein, G.K. Primary phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation for acute angle-closure glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, R.; Gazzard, G.; Aung, T.; Chen, Y.; Padmanabhan, V.; Oen, F.T.; Seah, S.K.; Hoh, S.T. Initial management of acute primary angle closure: A randomized trial comparing phacoemulsification with laser peripheral iridotomy. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2274–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.S.; Leung, D.Y.; Tham, C.C.; Li, F.C.; Kwong, Y.Y.; Chiu, T.Y.; Fan, D.S. Randomized trial of early phacoemulsification versus peripheral iridotomy to prevent intraocular pressure rise after acute primary angle closure. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1134–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaizumi, M.; Takaki, Y.; Yamashita, H. Phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation for acute angle closure not treated or previously treated by laser iridotomy. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2006, 32, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuara-Blanco, A.; Burr, J.; Ramsay, C.; Cooper, D.; Foster, P.J.; Friedman, D.S.; Scotland, G.; Javanbakht, M.; Cochrane, C.; Norrie, J.; et al. Effectiveness of early lens extraction for the treatment of primary angle-closure glaucoma (EAGLE): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016, 388, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.S.; Lai, J.S.; Tham, C.C.; Chua, J.K.; Poon, A.S. Argon laser peripheral iridoplasty versus conventional systemic medical therapy in treatment of acute primary angle-closure glaucoma: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 1591–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.S.; Tham, C.C.; Chua, J.K.; Poon, A.S.; Chan, J.C.; Lam, S.W.; Lam, D.S. To compare argon laser peripheral iridoplasty (ALPI) against systemic medications in treatment of acute primary angle-closure: Mid-term results. Eye 2006, 20, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.P.; Pang, J.C.; Tham, C.C. Acute primary angle closure-treatment strategies, evidences and economical considerations. Eye 2019, 33, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, S.; Hashemian, H.; Chen, R.; Johari, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Lin, S.C. Early phacoemulsification in patients with acute primary angle closure. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2015, 27, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazaki, J.; Amano, S.; Uno, T.; Maeda, N.; Yokoi, N.; Japan Bullous Keratopathy Study Group. National survey on bullous keratopathy in Japan. Cornea 2007, 26, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, T.; Ang, L.P.; Chan, S.P.; Chew, P.T. Acute primary angle-closure: Long-term intraocular pressure outcome in Asian eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 131, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, L.S.; Aung, T.; Husain, R.; Wu, Y.J.; Gazzard, G.; Seah, S.K. Acute primary angle closure: Configuration of the drainage angle in the first year after laser peripheral iridotomy. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 1470–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choong, Y.F.; Irfan, S.; Menage, M.J. Acute angle closure glaucoma: An evaluation of a protocol for acute treatment. Eye 1999, 13, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.; Friedman, D.S.; Chew, P.T.; Ang, L.P.; Gazzard, G.; Lai, Y.F.; Yip, L.; Lai, H.; Quigley, H.; Seah, S.K. Long-term outcomes in Asians after acute primary angle closure. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 1464–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A. Clear lens extraction in plateau iris with bilateral acute angle closure in young. J. Glaucoma. 2013, 22, e31–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Q.; Lu, B.; Wang, W.Q.; Fang, J. Angle parameter changes of phacoemulsification and combined phacotrabeculectomy for acute primary angle closure. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 8, 742–747. [Google Scholar]

- Hamanaka, T.; Kasahara, K.; Takemura, T. Histopathology of the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal in primary angle-closure glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 8849–8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.J. Cataract surgery from 1918 to the present and future-just imagine! Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 185, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Dai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D.Y.; Cringle, S.J.; Chen, J.; Kong, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, C. Primary angle closure glaucoma: What we know and what we don’t know. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 57, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wand, M.; Grant, W.M.; Simmons, R.J.; Hutchinson, B.T. Plateau iris syndrome. Trans. Sect. Ophthalmol. Am. Acad. Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. 1977, 83, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ritch, R.; Chang, B.M.; Liebmann, J.M. Angle closure in younger patients. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsia, Y.; Su, C.C.; Wang, T.H.; Huang, J.Y. Posture-related changes of intraocular pressure in patients with acute primary angle closure. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, M.; Ishida, A.; Ichioka, S.; Matsuo, M.; Shimizu, H.; Tanito, M. Aphakic pupillary block by an intact anterior vitreous membrane after total lens extraction by phacoemulsification. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2021, 12, 882–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadaraj, V.; Sengupta, S.; Palaniswamy, K.; Srinivasan, K.; Kader, M.A.; Raman, G.; Reddy, S.; Ramulu, P.Y.; Venkatesh, R. Evaluation of angle closure as a risk factor for reduced corneal endothelial cell density. J. Glaucoma. 2017, 26, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Mean ± SD | Range | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eyes | 41 | - | |

| Male | 9 | - | |

| Female | 32 | - | 0.0004 † |

| Age (years) | 73.7 ± 8.7 | 49–93 | |

| Time from onset to operation (h) | 48.0 ± 46.6 | 5–175 | |

| Time from arrival to operation (h) | 5.9 ± 7.3 | 1–31 | |

| Operation time (m) | 20.2 ± 7.9 | 11.8–44.8 | |

| BCVA (LogMAR) | |||

| First visit | 1.13 ± 0.85 | −0.18 to 3 | |

| 1 day | 0.56 ± 0.72 * | −0.18 to 2.30 | 0.0002 |

| 1 week | 0.27 ± 0.42 * | −0.18 to 2 | <0.0001 |

| 1 month | 0.12 ± 0.24 * | −0.18 to 1 | <0.0001 |

| IOP (mmhg) | |||

| First visit | 48.8 ± 19.4 | 7.7–83.7 | |

| 1 day | 14.6 ± 8.1 * | 6.3–37.3 | <0.0001 |

| 1 week | 12.8 ± 3.0 * | 8–19.7 | <0.0001 |

| 1 month | 12.5 ± 2.6 * | 9–21.3 | <0.0001 |

| CECs (/mm2) | |||

| First visit | 2266 ± 796 | 571–3425 | |

| 1 month | 2419 ± 704 | 874–3497 | 0.301 |

| Medication) | |||

| First visit ((+) 26, (−) 15 eyes) | 1.4 ± 1.6 | 0–6 | |

| 1 month | 0 ± 0 * | 0–0 | <0.0001 |

| Parameters | Medication (+) | Medication (−) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eyes | 26 | 15 | |

| Male | 6 | 3 | |

| Female | 20 | 12 | 1 † |

| Age (years) | 73.0 ± 8.5 | 74.9 ± 8.9 | 0.69 |

| Time from onset to operation (h) | 48.5 ± 51.9 | 47.3 ± 53.8 | 0.19 |

| Time from arrival to operation (h) | 7.3 ± 8.5 | 3.3 ± 3.5 | 0.06 |

| Operation time (m) | 20.0 ± 7.9 | 20.3 ± 7.9 | 0.87 |

| BCVA (LogMAR) | |||

| First visit | 1.29 ± 0.81 | 0.86 ± 0.80 | 0.12 |

| 1 day | 0.58 ± 0.70 | 0.53 ± 0.72 | 0.94 |

| 1 week | 0.34 ± 0.47 | 0.16 ± 0.23 | 0.30 |

| 1 month | 0.17 ± 0.27 | 0.03 ± 0.14 | 0.15 |

| IOP (mmhg) | |||

| First visit | 48.3 ± 20.4 | 49.7 ± 16.7 | 1.00 |

| 1 day | 13.6 ± 6.5 | 16.2 ± 9.9 | 0.27 |

| 1 week | 12.6 ± 3.0 | 13.2 ± 3.0 | 0.60 |

| 1 month | 12.3 ± 2.5 | 12.8 ± 2.8 | 0.45 |

| Cecs (/mm2) | |||

| First visit | 2138 ± 918 | 2465 ± 495 | 0.41 |

| 1 month | 2432 ± 772 | 2400 ± 585 | 0.69 |

| Medication) | |||

| First visit * | 2.2 ± 1.4 | 0 ± 0 | <0.0001 |

| 1 month | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | Not a number |

| Parameters | Medication (+) | Medication (−) |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative corneal edema | 20 | 10 |

| Intraoperative iris prolapse | 3 | 0 |

| Intraoperative hyphema | 3 | 0 |

| Zinn’s zonule rupture within 45 degrees. | 0 | 1 |

| Crack in CCC | 1 | 0 |

| Iris dissection at 45 degrees | 1 | 0 |

| Postoperative fibrin in anterior chamber | 2 | 9 |

| Postoperative hyphema | 1 | 3 |

| Reoperation | 0 | 0 |

| Pre-BCVA | Change in BCVA | 1m-BCVA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-IOP | * p = 0.0080, r = 0.41 | * p = 0.0010, r = −0.50 | p = 0.31, r = −0.16 |

| Authors | Study Design | Preoperative IOP Lowering Medication | Average Follow-Up (Months) | No. of Patients | Type of Treatments | Time from Onset to Operation | Preoperative IOP (mmHg) | Postoperative IOP (mmHg) | No. of Additional Surgery Required (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lam et al. [5] | RCT | + | 18 | 31 | Phaco/IOL | Onset to consultation 3.1 ± 3.7 (days). Consultation to abortion of attack 11.4 ± 9.0 (h). Abortion of attack to PEAIOL 5.7 ± 3.3 (days) | 59.7 ± 8.71 | 12.6 ± 1.9 | 0 |

| 31 | LPI | Onset to consultation 2.2 ± 2.5 (days). Consultation to abortion of attack 9.1 ± 6.9 (h). Abortion of attack to LPI 4.3 ± 2.7 (days) | 57.9 ± 11.8 | 15.0 ± 3.4 | 4 (12.9) repeated LPI | ||||

| Husain et al. [4] | RCT | + | 24 | 19 | Phaco/IOL | Onset to consultation 2.8 (days). Consultation to PEA-IOL 5–7 (days) | 57.4 16.9 | 15.4 7.7 | 1 (5.3) TBx on day 1 |

| 18 | LPI | Onset to consultation 7.4 (days). Consultation to LPI 3 (days) | 55.8 13.2 | 13.7 6.1 | 6 (33.3) phaco TBx, 1 (5.6) repeated LPI | ||||

| Jacobi et al. [3] | Non-RCT | + | 10.2 ± 3.4 | 43 | Phaco/IOL | Onset to PEA-IOL 2.1 ± 0.9 (days) | 40.5 ± 7.6 | 17.80 ± 3.40 | 2 (4.6) filtration procedure, 3 (6.9) CPC |

| 32 | SPI | Onset to SPI 2.0 ± 0.8 (days) | 39.7 ± 7.8 | 20.10 ± 4.20 | 11 (34.3) Phaco/IOL, 5 (15.6) filtration procedure, 4 (12.5) CPC | ||||

| Imaizumi et al. [6] | NM | + | 6 | 18 | Phaco/IOL | Onset to PEA-IOL 0.11 ± 0.32 (days) | 48.9 ± 13.9 | 13.0 ± 3.1 | 0 |

| 8 | LPI→Phaco/IOL | Onset to PEA-IOL 90 ± 90(months) | 17.0 ± 3.9 | 13.5 ± 1.1 | 0 | ||||

| Moghimi et al. [11] | Prospective non-randomised | + | 18.5 ± 5.2 | 20 | LPI→Phaco/IOL | Onset to consultation 4.6 ±4.7(days). Abortion of attack and LPI 2.1 ± 1.6 (days). Abortion of attack and PEA-IOL 23.6 ± 9.2(days) | 54.0 ± 9.4 | 13.90 ± 2.17 | 0 |

| 15 | LPI only | Onset to consultation 5.1 ± 4.8(days). Abortion of attack and LPI 1.7 ± 1.5(days). | 57.1 ± 10.2 | 17.80 ± 4.16 | 3 (20.0) underwent phaco/IOL and 2 (13.3) underwent phaco TBx. | ||||

| Our study | Retrospective, case series | +/− | 1 | 41 | Phaco/IOL(-GSL) | Onset to PEA-IOL 2.0 ± 1.9 (days) | 48.8 ± 19.4 | 12.5 ± 2.6 | 0 |

| Authors | Study Design | Average Follow-Up (Months) | No. of Eyes (Patients) | Type of Treatments | Age | Time from Onset to Operation | Preoperative IOP (mmHg) | Postoperative IOP (mmHg) | No. of Additional Surgery Required (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aung et al. [13] | Retrospective | 50.3 (9–107) | 110 (96) | LPI | 63.7 (39–92) | Onset to consultation 6.5 (days). Consutation to LPI < 3 (days) | 52.8 (28–80) | NM | 36 (32.7) TBx |

| Aung et al. [16] | Cross-sectional | 75.6 ± 18.0 (49.2–121.2) | 90 (90) | LPI | 62.0 ± 9.0 (43–89) | Onset to consultation 31 eyes < 1 day, 20 eyes 1–3 days, 36 eyes > 3 days | NM | 15.4 | 34 (37.8) filtering surgery |

| Lim et al. [14] | Prospective observational case series | 12 | 44(44) | LPI | 60.2 ± 10.7 (35–99) | Onset to consultation 35.8 ± 56.4(h). Consultation to LPI 2.5 ± 1.3(days) | 53.3 ± 15.2 (26–78) | NM | NM |

| Tan et al. [17] | Retrospective | 27.3 ± 16.2 | 42 (41) | LPI | 59.6 ± 11.3 (37–85) | Onset to consultation 28.2 (h), consultation to LPI < 24 (h) | 55.0 ± 12 | 13.3 ± 2.92 | 12 (28.6) Phaco/IOL, 7 (16.7) Phaco TBx, 1 (2.4) Phaco GDD |

| Lai et al. [10] | RCT | 16.4 ± 5.6 (7–29) | 38 (32) | Medications→LPI | 66.5 ± 8.5 | Onset to treatment 29.7 ± 23.8 (h). Consultation to LPI < 48 (h) | 57.1 ± 9.2 (40–74) | 14.7 ± 4.6 (8–32) | 1 (2.6) Phaco/IOL |

| 15.0 ± 6.0 (6–36) | 41 (39) | ALPI→LPI | 70.0 ± 10.5 | Onset to treatment 41.6 ± 47.6 (h). Consultation to LPI < 48 (h) | 61.2 ± 10.6 (40–79) | 13.6 ± 2.7 (9–21) | 1 (2.4) Phaco/IOL for CACG, 2 (4.9) Phaco/IOL for cataract | ||

| Our study | Retrospective, case series | 1 | 41(41) | Phaco/IOL(-GSL) | 73.7 ± 8.7 (49–93) | Onset to PEA-IOL 2.0 ± 1.9 (days) | 48.8 ± 19.4 | 12.5 ± 2.6 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suzuki, T.; Fujishiro, T.; Tachi, N.; Ueta, Y.; Fukutome, T.; Okamoto, Y.; Sasajima, H.; Aihara, M. Safety and Efficacy of Rapid Primary Phacoemulsification on Acute Primary Angle Closure with and without Preoperative IOP-Lowering Medication. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020660

Suzuki T, Fujishiro T, Tachi N, Ueta Y, Fukutome T, Okamoto Y, Sasajima H, Aihara M. Safety and Efficacy of Rapid Primary Phacoemulsification on Acute Primary Angle Closure with and without Preoperative IOP-Lowering Medication. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(2):660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020660

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuzuki, Takafumi, Takashi Fujishiro, Naoko Tachi, Yoshiki Ueta, Takao Fukutome, Yasuhiro Okamoto, Hirofumi Sasajima, and Makoto Aihara. 2023. "Safety and Efficacy of Rapid Primary Phacoemulsification on Acute Primary Angle Closure with and without Preoperative IOP-Lowering Medication" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 2: 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020660

APA StyleSuzuki, T., Fujishiro, T., Tachi, N., Ueta, Y., Fukutome, T., Okamoto, Y., Sasajima, H., & Aihara, M. (2023). Safety and Efficacy of Rapid Primary Phacoemulsification on Acute Primary Angle Closure with and without Preoperative IOP-Lowering Medication. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(2), 660. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020660