Clinical Analysis of Intestinal Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Recruitment and Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Manifestations

3.3. Laboratory Tests

3.4. Radiological Examination

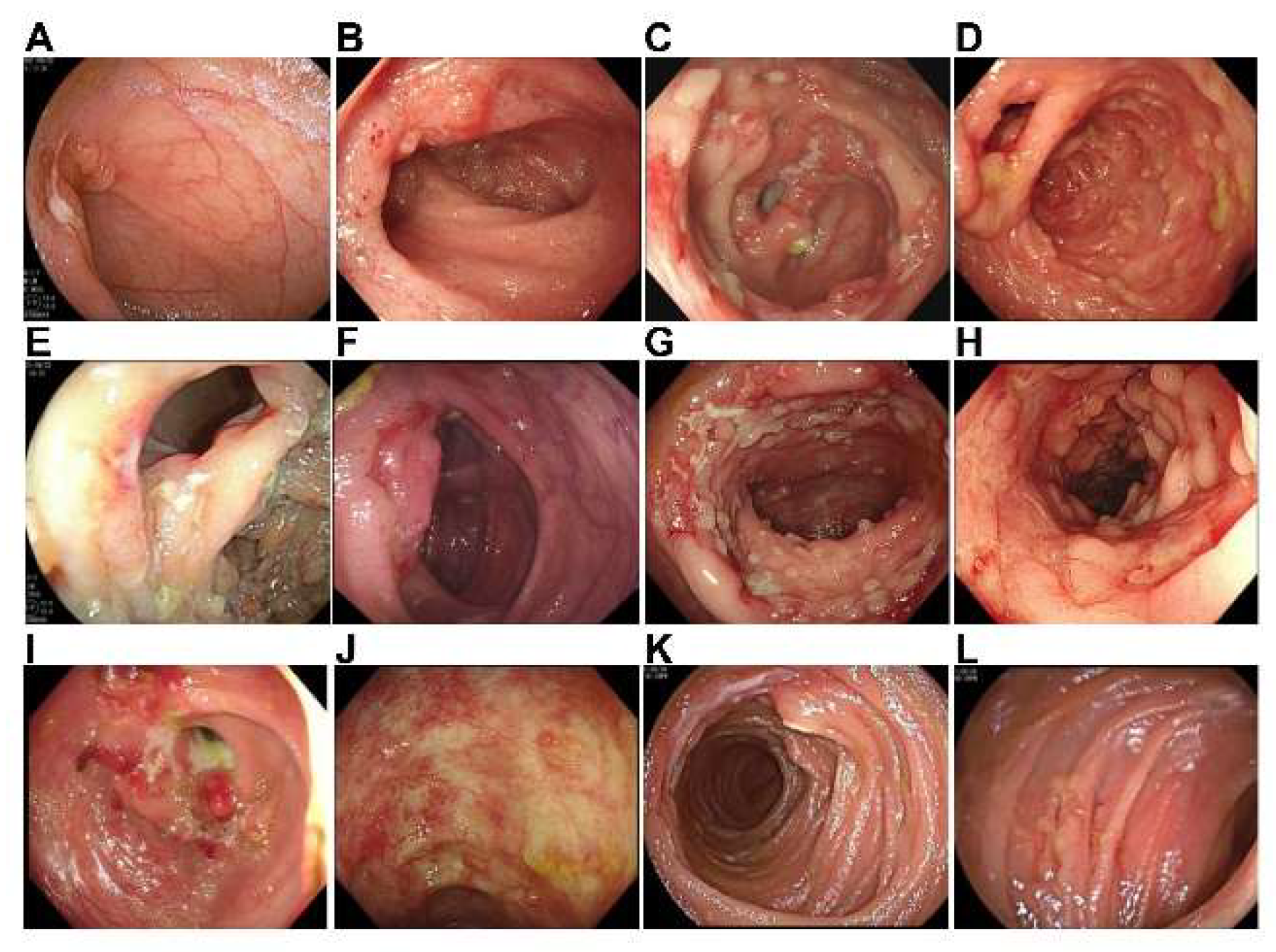

3.5. Endoscopy, Histological Examination, and Microbiological Examination

3.6. Empiric Antituberculosis Therapy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Churchyard, G.; Kim, P.; Shah, N.S.; Rustomjee, R.; Gandhi, N.; Mathema, B.; Dowdy, D.; Kasmar, A.; Cardenas, V. What We Know About Tuberculosis Transmission: An Overview. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S629–S635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.H.; Coyle, W.J. Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Song, F.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhao, L. Asymptomatic gastric tuberculosis in the gastric body mimicking an isolated microscopic erosion: A rare case report. Medicine 2022, 101, e28888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Placido, R.; Pietroletti, R.; Leardi, S.; Simi, M. Primary gastroduodenal tuberculous infection presenting as pyloric outlet obstruction. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1996, 91, 807–808. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donoghue, H.D.; Holton, J. Intestinal tuberculosis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 22, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Yu, J.; Du, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Li, M.; Qin, J.; Shu, W.; et al. The epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in China: A large-scale multicenter observational study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreeramareddy, C.T.; Panduru, K.V.; Verma, S.C.; Joshi, H.S.; Bates, M.N. Comparison of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis in Nepal—A hospital-based retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailhol, J.; Decludt, B.; Che, D. Sociodemographic factors that contribute to the development of extrapulmonary tuberculosis were identified. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, J. Intestinal tuberculosis: Clinico-pathological profile and the importance of a high degree of suspicion. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2019, 24, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, P.B.; Amarapurkar, A.D. Morphological spectrum of gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Trop. Gastroenterol. Off. J. Dig. Dis. Found. 2009, 30, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Limsrivilai, J.; Pausawasdi, N. Intestinal tuberculosis or Crohn’s disease: A review of the diagnostic models designed to differentiate between these two gastrointestinal diseases. Intest. Res. 2021, 19, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.C.; Tsai, M.K.; Lin, S.W.; Wang, J.Y.; Yu, C.J.; Lee, C.Y. Latent Tuberculosis Infection Increases in Kidney Transplantation Recipients Compared With Transplantation Candidates: A Neglected Perspective in Tuberculosis Control. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2020, 71, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.H.; Chen, W. Progress on the research of risk factors of tuberculosis incidence. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi = Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi 2012, 33, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, E.; Gómez-Reino, J.J. The risk of tuberculosis in patients treated with TNF antagonists. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 7, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, D.F.; Farkas, D.K.; Horsburgh, C.R.; Thomsen, R.W.; Sørensen, H.T. Increased risk of active tuberculosis after cancer diagnosis. J. Infect. 2017, 74, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.K.; Islam, M.N.; Ferdous, J.; Alam, M.M. An Overview on Epidemiology of Tuberculosis. Mymensingh Med. J. MMJ 2019, 28, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Kentley, J.; Ooi, J.L.; Potter, J.; Tiberi, S.; O’Shaughnessy, T.; Langmead, L.; Chin Aleong, J.; Thaha, M.A.; Kunst, H. Intestinal tuberculosis: A diagnostic challenge. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudahy, P.G.T.; Warren, J.L.; Cohen, T.; Wilson, D. Trends in C-Reactive Protein, D-Dimer, and Fibrinogen during Therapy for HIV-Associated Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 99, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; Yao, L.; Fan, L. Evaluation of risk factors for false-negative results with an antigen-specific peripheral blood-based quantitative T cell assay (T-SPOT®.TB) in the diagnosis of active tuberculosis: A large-scale retrospective study in China. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 1815–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendy, A.; Albatineh, A.N.; Vieira, E.R.; Gasana, J. Higher specificity of tuberculin skin test compared with QuantiFERON-TB Gold for detection of exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2014, 59, 1188–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haas, M.K.; Belknap, R.W. Diagnostic Tests for Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Clin. Chest Med. 2019, 40, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Song, Q. Diagnostic values of peripheral blood T-cell spot of tuberculosis assay (T-SPOT.TB) and magnetic resonance imaging for osteoarticular tuberculosis: A case-control study. Aging 2021, 13, 9693–9703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, J.; Hu, K. Performance Evaluation of IGRA-ELISA and T-SPOT.TB for Diagnosing Tuberculosis Infection. Clin. Lab. 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.S.; Wang, Z.T.; Wu, Z.Y.; Yin, Q.H.; Zhong, J.; Miao, F.; Yan, F.H. Differentiation of Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis by clinical and CT enterographic models. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, S.; Das, P.; Madhusudhan, K.S.; Dattagupta, S.; Sharma, R.; Sahni, P.; Makharia, G.; Ahuja, V. Differentiating Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.Y.; Tong, J.L.; Ran, Z.H. Intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease: Challenging differential diagnosis. J. Dig. Dis. 2016, 17, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudcharoen, A.; Niltwat, S.; Pausawasdi, N.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; Limsrivilai, J. Repeat colonoscopy and increased number of biopsy samples enhance the diagnostic yield in patients with suspected intestinal tuberculosis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, S-547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, C.; Yang, H.; Huang, M.; Zhuang, X.; Mao, R.; et al. Development and Validation of a Novel Diagnostic Nomogram to Differentiate Between Intestinal Tuberculosis and Crohn’s Disease: A 6-year Prospective Multicenter Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Krishnamurthy, G.; Rajendran, J.; Sharma, V.; Mandavdhare, H.; Kumar, H.; Deen Yadav, T.; Vasishta, R.K.; Singh, R. Surgery for Abdominal Tuberculosis in the Present Era: Experience from a Tertiary-Care Center. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt.) 2018, 19, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age | 43.2 ± 15.3 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 67.4% |

| Female | 32.6% |

| Occupation | |

| Freelancer | 37.0% |

| Middle-class worker | 30.4% |

| Blue-collar worker | 15.2% |

| Student | 8.7% |

| Farmer | 6.5% |

| Soldier | 2.2% |

| Risk Factors | Cases (n = 46) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Immunosuppressive drug use | 8 | 17.4% |

| Rheumatic disease | 8 | 17.4% |

| Potential contact with a TB patient | 5 | 10.9% |

| Previous TB history | 4 | 8.7% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 | 6.5% |

| Kidney transplantation | 2 | 4.3% |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 | 4.3% |

| Chronic renal failure | 1 | 2.2% |

| Cancer | 1 | 2.2% |

| Unclean foods | 1 | 2.2% |

| Symptoms and Signs | Cases (n = 46) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Weight loss | 31 | 67.4% |

| Abdominal pain | 30 | 65.2% |

| Fever | 18 | 39.1% |

| Abdominal tenderness | 16 | 34.8% |

| Abdominal bloating | 14 | 30.4% |

| Diarrhea | 10 | 21.7% |

| Weakness | 8 | 17.4% |

| Bloody defecation | 8 | 17.4% |

| Poor appetite | 7 | 15.2% |

| Palpable abdominal mass | 7 | 15.2% |

| Night sweats | 5 | 10.9% |

| Cough | 2 | 4.3% |

| Constipation | 2 | 4.3% |

| Abdominal distension | 2 | 4.3% |

| Alternating diarrhea and constipation | 1 | 2.2% |

| Laboratory Indicators | Data | Reference Value |

|---|---|---|

| CRP (mg/dL) | 2.0 (0.1–19.6) | 0–0.8 |

| WBC (/L) | 7.5 ± 3.4 × 109 | 3.5–10 × 109 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 38.4 ± 25.9 | <20 |

| Hb (g/L) | Male: 118.3 ± 26.5, female: 103.2 ± 18.2 | Male: 137–179, female: 116–155 |

| HCT (L/L) | Male: 0.37 (0.18–0.49), female: 0.32 (0.21–0.40) | Male: 0.4–0.52, female: 0.37–0.47 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 23 (1–73) | 20–40 |

| Platelet (/L) | 282.3 ± 108.5 × 109 | 100–300 × 109 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 0.8 (0.15–5.52) | 0–0.5 |

| CEA (μg/L) | 1.5 (0.2–7.4) | 0–5 |

| CA125 (μ/mL) | 18.0 (4.5–237.5) | 0.1–35 |

| CA199 (μ/mL) | 6.2 (0.6–94.8) | 0.1–37 |

| CA153 (μ/mL) | 12.9 ± 7.0 | 0.1–30 |

| CA724 (μ/mL) | 1.4 (0.8–10.3) | 0.1–10 |

| Serum ferritin (ng/mL) | Male: 292.8 (7.8–2000), female: 148 (47.8–712.1) | Male: 30–400, female: 13–150 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 36.6 ± 5.8 | 35–55 |

| Radiological Manifestations | Cases (n = 37) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Enlarged celiac lymph nodules | 16 | 43.2% |

| Thickening of the terminal ileum/ileocecal region | 10 | 27.0% |

| Thickening of the colon wall | 9 | 24.3% |

| Thickening of the small intestinal wall | 6 | 16.2% |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 1 | 2.7% |

| Calcified celiac lymph nodules | 1 | 2.7% |

| Features | Cases (n = 42) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Ulcer in the terminal ileal /ileocecal region | 25 | 59.5% |

| Colonic ulcer | 15 | 35.7% |

| Ileocecal valve deformation | 11 | 26.2% |

| Pseudopolyps | 9 | 21.4% |

| Inflammation and erosion in the terminal ileal/ileocecal region | 7 | 16.7% |

| Stricture | 6 | 14.3% |

| Colonic inflammation | 5 | 11.9% |

| Inflammation and erosion in the ileocecal valve | 1 | 2.4% |

| Scar | 1 | 2.4% |

| Jejunal ulcer | 1 | 2.4% |

| Small intestinal inflammation | 1 | 2.4% |

| Colonic mass | 1 | 2.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeng, J.; Zhou, G.; Pan, F. Clinical Analysis of Intestinal Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020445

Zeng J, Zhou G, Pan F. Clinical Analysis of Intestinal Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(2):445. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020445

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeng, Jiaqi, Guanzhou Zhou, and Fei Pan. 2023. "Clinical Analysis of Intestinal Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 2: 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020445

APA StyleZeng, J., Zhou, G., & Pan, F. (2023). Clinical Analysis of Intestinal Tuberculosis: A Retrospective Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(2), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020445