Characteristics and Effectiveness of Mobile- and Web-Based Tele-Emergency Consultation System between Rural and Urban Hospitals in South Korea: A National-Wide Observation Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

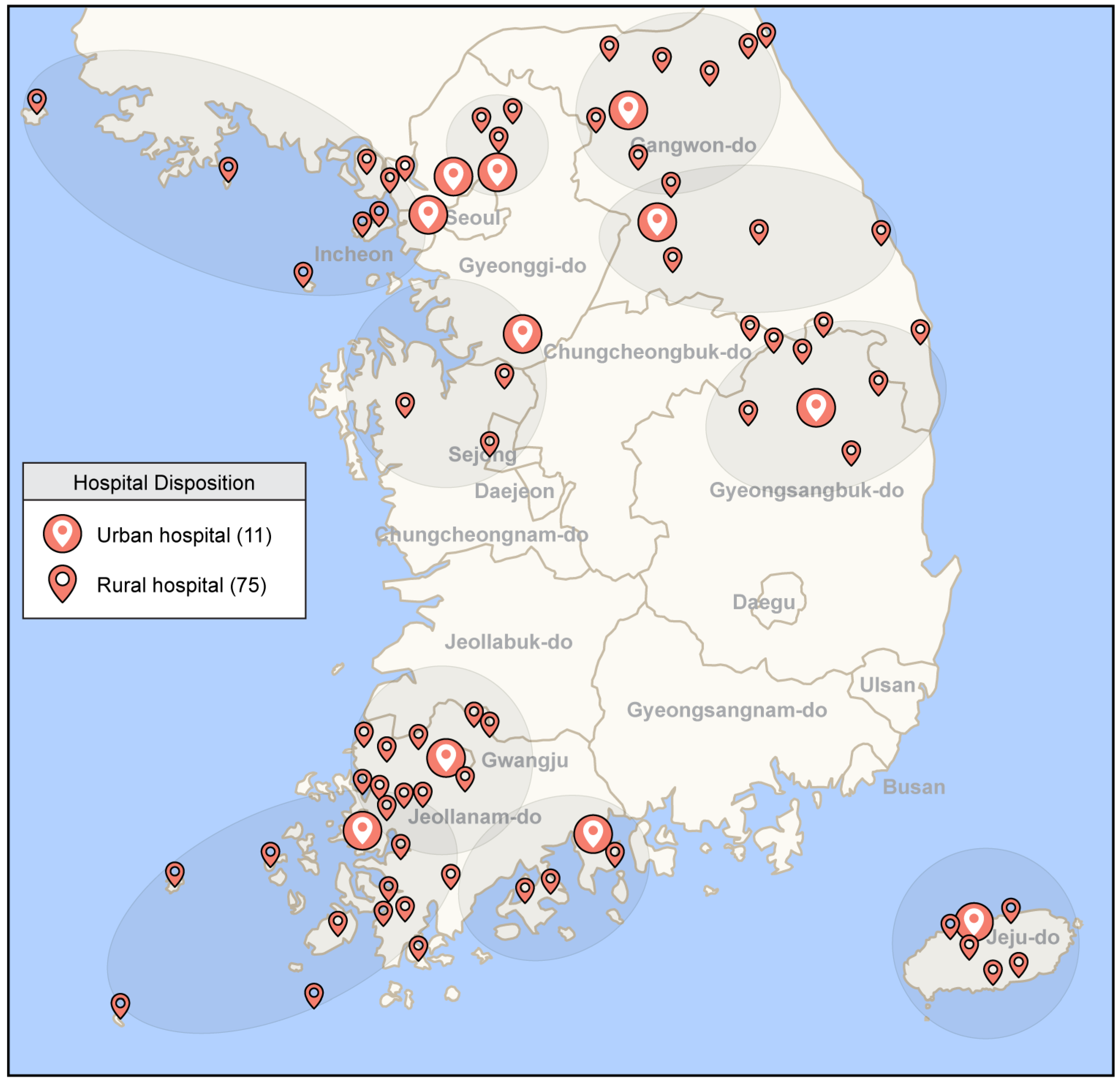

2.1. Geographical and Healthcare Infrastructural Characteristics and Tele-Emergency Systems in South Korea

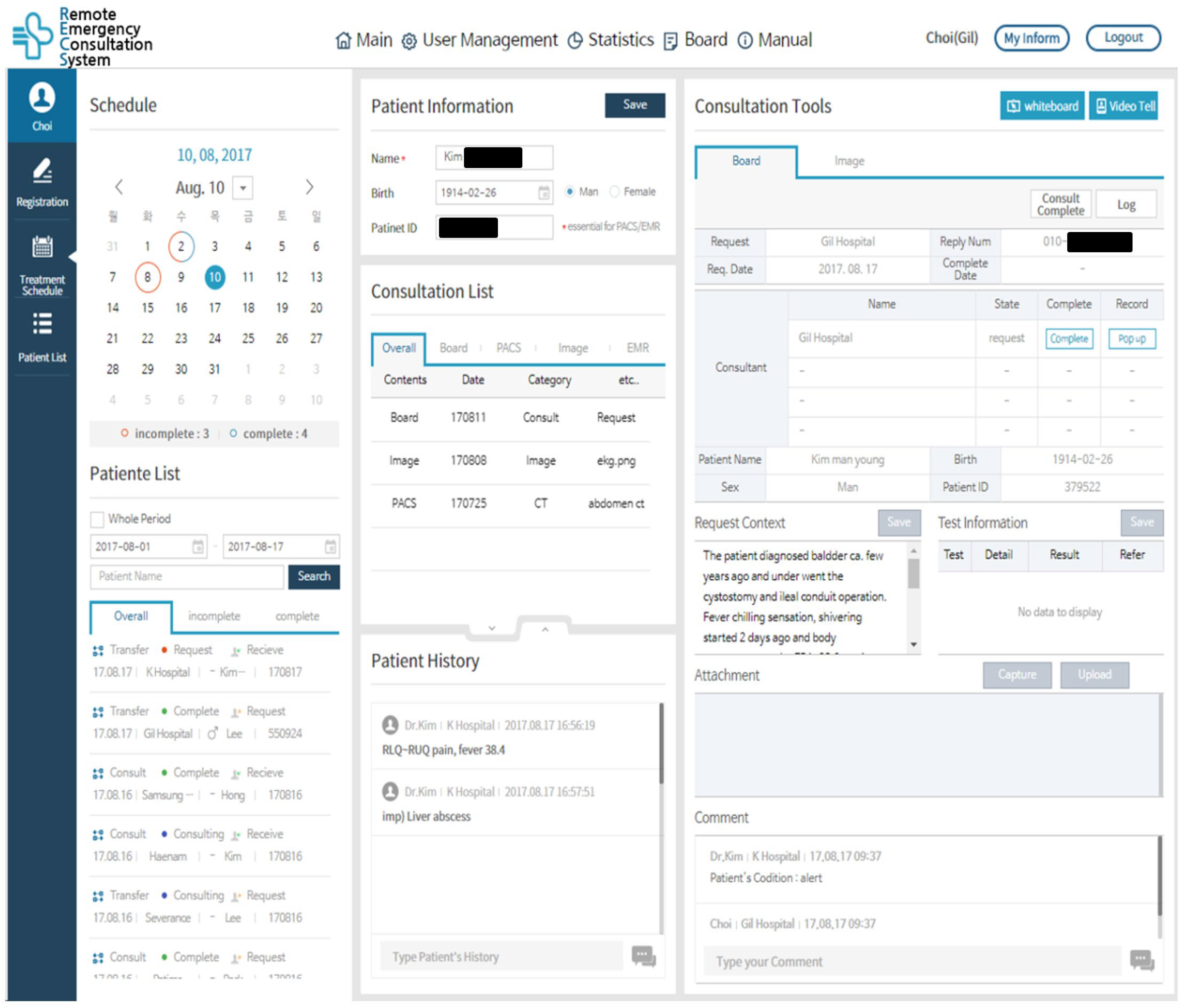

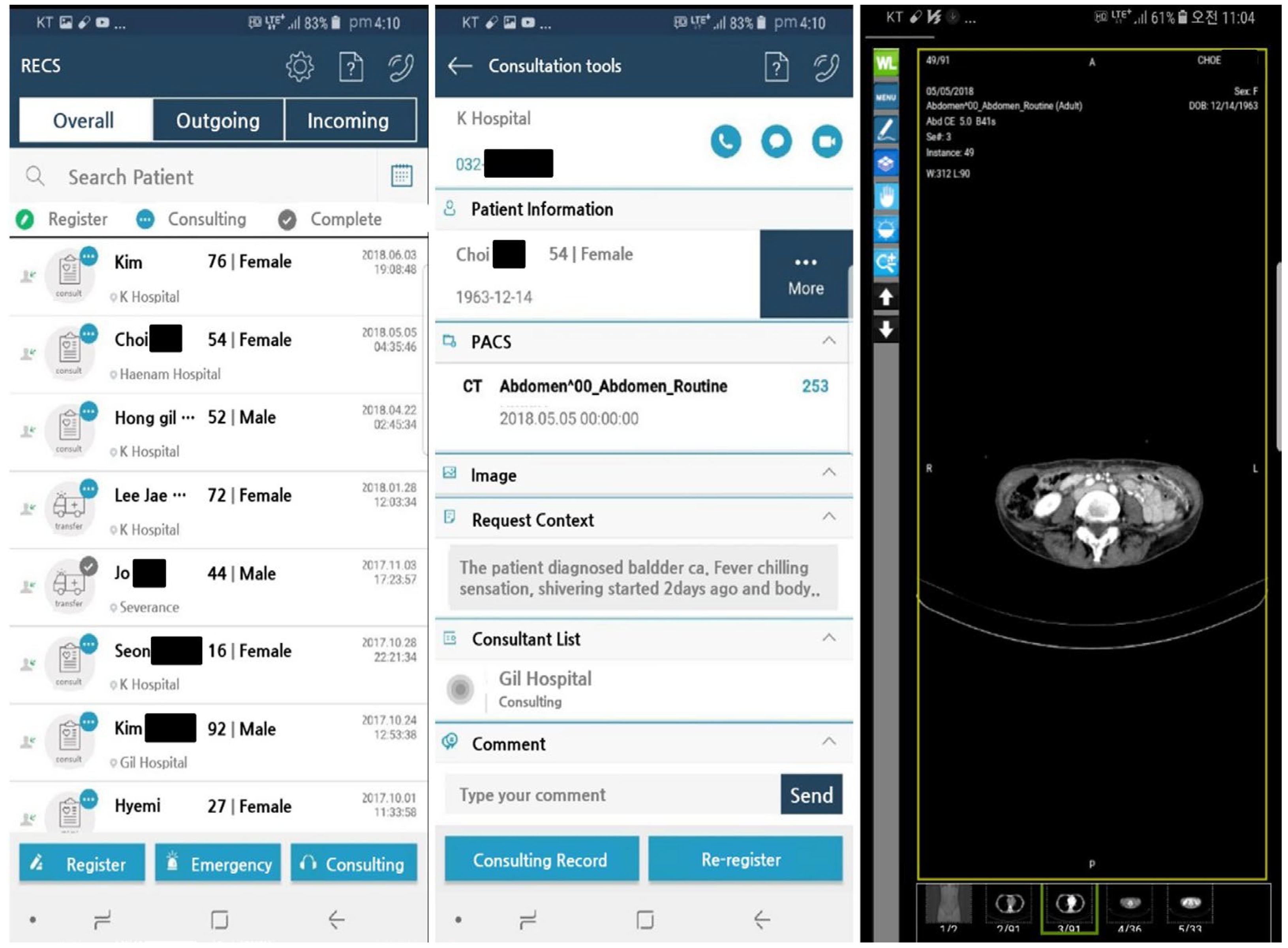

2.2. Development and Application of a Remote Emergency Consultation System (RECS)

2.3. Tele-Emergency Systems in South Korea: Definition and Application Process

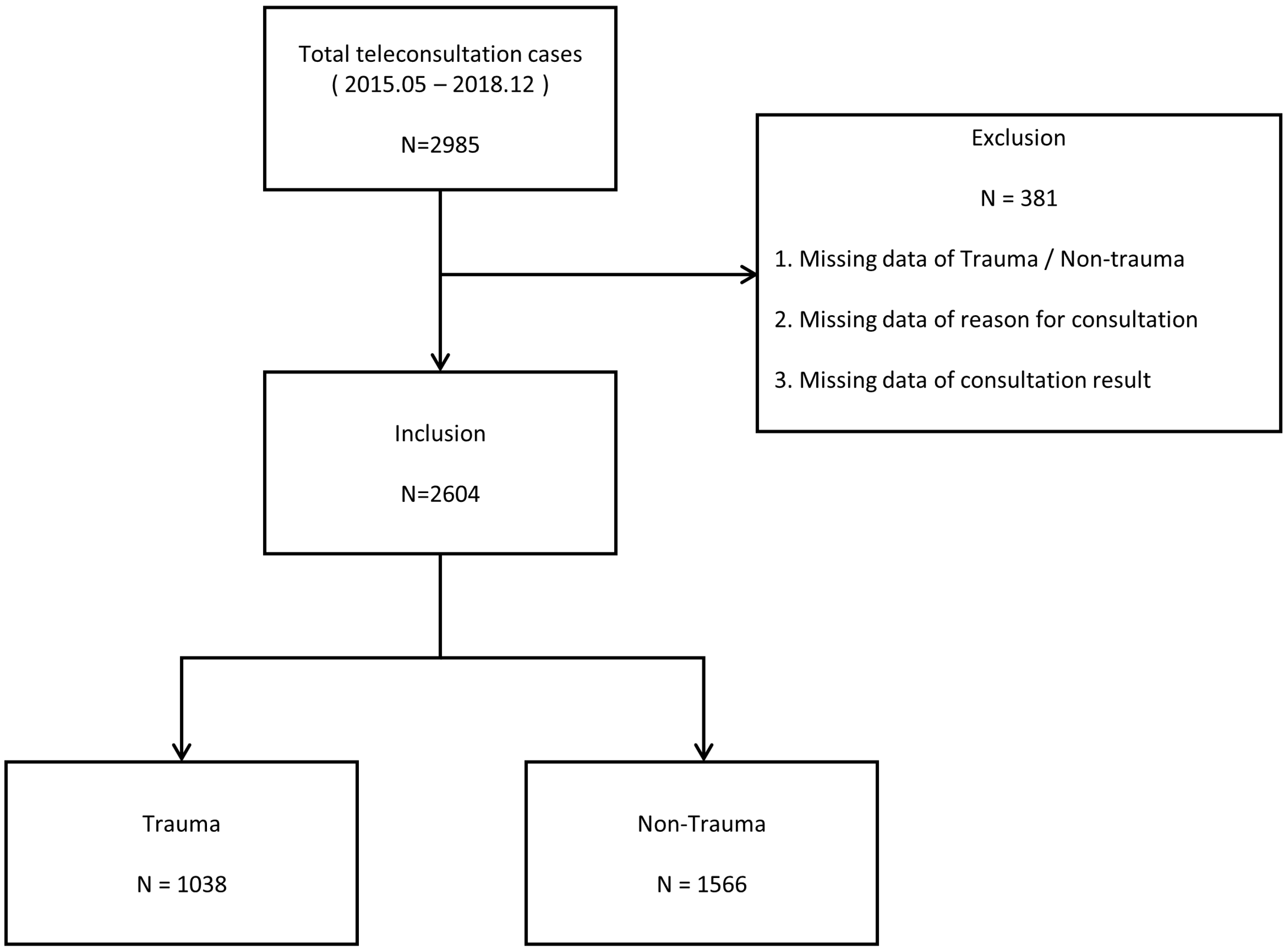

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Statement

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mueller, K.J.; Potter, A.J.; MacKinney, A.C.; Ward, M.M. Lessons from tele-emergency: Improving care quality and health outcomes by expanding support for rural care systems. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterling, S.A.; Seals, S.R.; Jones, A.E.; King, M.H.; Galli, R.L.; Isom, K.C.; Summers, R.L.; Henderson, K.A. The impact of the TelEmergency program on rural emergency care: An implementation study. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Practice Guidance for Emergency Telehealth and Acute Unscheduled Care Telehealth. ACEP Emergency Telehealth Section, Original. 2020. Available online: https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/telehealth/media/documents/acep-practice-guidance-for-emergency-telehealth-and-acute-unschedulel-care-telehealth-final.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Sikka, N.; Gross, H.; Joshi, A.U.; Shaheen, E.; Baker, M.J.; Ash, A.; Hollander, J.E.; Cheung, D.S.; Chiu, A.R.; Wessel, C.B.; et al. Defining emergency telehealth. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021, 27, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration Telehealth Programs. 2019. Available online: https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/telehealth/ (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Telemedicine. 2019. Available online: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/telemedicine/index.html (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Liu, P.; Wang, F.; Xu, W.; Li, Y.; Li, B. Trends and frontiers of research on telemedicine from 1971 to 2022: A scientometric and visualisation analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 29, 1357633X231183732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachrison, K.S.; Boggs, K.M.; MHayden, E.; Espinola, J.A.; Camargo, C.A. A national survey of telemedicine use by US emergency departments. J. Telemed. Telecare 2020, 26, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Reports World. Global Telehealth Market Size, Status and Forecast 2020–2026. 2020. Available online: https://www.marketreportsworld.com/enquest-sample/14569204 (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Scott Kruse, C.; Karem, P.; Shifflett, K.; Vegi, L.; Ravi, K.; Brooks, M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: Asystematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavitt, A. The COVID-19 pandemic underscores the need to address structural challenges of the US health care system. JAMA Health Forum Am. Med. Assoc. 2020, 1, e200839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.; Bradley, S.; Israeli-Korn, S.; Menon, B.; Chattu, V.K.; Thomas, P.; Chawla, J.; Kumar, R.; Prandi, P.; Ray, D.; et al. Chronic neurology in COVID-19 era: Clinical considerations and recommendations from the REPROGRAM consortium. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.; Rastogi, A.; Chattu, V.K.; Adisesh, A.; Thomas, P.; Alvarado, N.; Riahi, A.D.; Varun, C.N.; Pai, A.R.; Barsam, S.; et al. Key strategies for clinical management and improvement of healthcare services for cardiovascular disease and diabetes patients in the coronavirus (COVID-19) settings: Recommendations from the REPROGRAM consortium. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.; Sharma, D.; Walker, A.H.; McDonald, M.; Huasen, B.; Haridas, A.; Mahata, M.K.; Jabbour, P. Acute neurological care in the COVID-19 Era: The pandemic health system RE silience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) consortium pathway. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.R.; Munhall, C.C.; Nguyen, S.A.; O’Rourke, A.K.; Miccichi, K.; Meyer, T.A. Diagnostic accuracy and management concordance of otorhinolaryngological diseases through telehealth or remote visits: A systematic review & meta-analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 1357633X231156207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moecke, D.P.; Holyk, T.; Beckett, M.; Chopra, S.; Petlitsyna, P.; Girt, M.; Kirkham, A.; Kamurasi, I.; Turner, J.; Sneddon, D.; et al. Scoping review of telehealth use by Indigenous populations from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 1357633X231158835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gierek, M.; Kitala, D.; Łabuś, W.; Glik, J.; Szyluk, K.; Pietrauszka, K.; Bergler-Czop, B.; Niemiec, P. The Impact of Telemedicine on Patients with Hidradenitis Suppurativa in the COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postorino, M.; Treglia, M.; Giammatteo, J.; Pallocci, M.; Petroni, G.; Quintavalle, G.; Picchioni, O.; Cantonetti, M.; Marsella, L.T. Telemedicine as a medical examination tool during the Covid-19 emergency: The experience of the Onco-Haematology Center of Tor Vergata Hospital in Rome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furlepa, K.; Śliwczyński, A.; Kamecka, K.; Kozłowski, R.; Gołębiak, I.; Cichońska-Rzeźnicka, D.; Marczak, M.; Glinkowski, W.M. The COVID-19 Pandemic as an Impulse for the Development of Telemedicine in Primary Care in Poland. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Villegas, A.; Maroto-Martin, S.; Baena-Lopez, M.A.; Garzon-Miralles, A.; Bautista-Mesa, R.J.; Peiro, S.; Leal-Costa, C. Telemedicine in times of the pandemic produced by COVID-19: Implementation of a teleconsultation protocol in a hospital emergency department. Healthcare 2020, 8, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, C.; Robinson, S.; Boyd, J.; Jamieson, A.; Blakeman, R.; Yeung, J.; McDonnell, J.; Waters, S.; Bosich, K.; Hendrie, D. Effectiveness of Telehealth in Rural and Remote Emergency Departments: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e30632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Toit, M.; Malau-Aduli, B.; Vangaveti, V.; Sabesan, S.; Ray, R.A. Use of telehealth in the management of non-critical emergencies in rural or remote emergency departments: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, R.; Keith, J.C.; McKenzie, K.; Hall, G.S.; Henderson, K. TelEmergency: A Novel System for Delivering Emergency Care to Rural Hospitals. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2008, 51, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, J.C.; Kyle, A.; Simmons, J.; Islam, S.; Schmieg Jr, R.E.; Olivier, J.; McSwain, N.E., Jr. Impact of Telemedicine Upon Rural Trauma Care. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2008, 64, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, B.; van Beijnum, B.J.F.; Hermens, H.J. Usability in telemedicine systems—A literature survey. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 93, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, N.; Pirri, M.; Carlin, K.; Straus, R.; Rahimi, F.; Pine, J. The Use of Mobile Phone Cameras in Guiding Treatment Decisions for Laceration Care. Telemed. E-Health 2012, 18, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totten, A.M.; Womack, D.M.; Griffin, J.C.; McDonagh, M.S.; Davis-O’Reilly, C.; Blazina, I.; Grusing, S.; Elder, N. Telehealth-guided provider-to-provider communication to improve rural health: A systematic review. J. Telemed. Telecare 2022, 1357633X221139892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamano, T.; Kotani, K.; Kitano, N.; Morimoto, J.; Emori, H.; Takahata, M.; Fujita, S.; Wada, T.; Ota, S.; Satogami, K.; et al. Telecardiology in rural practice: Global trends. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Lai, W.-R. Mobile emergency telemedicine system over heterogeneous networks. J. Inf. Technol. Appl. 2012, 6, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Amadi-Obi, A.; Gilligan, P.; Owens, N.; O’Donnell, C. Telemedicine in pre-hospital care: A review of telemedicine applications in the pre-hospital environment. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, J.S. Analysis and Study for Support of Emergency Medical Service in Rural Areas; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2007; p. 6.

- Chun, H.-S.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.-S.; Park, H.-Y.; Hwang, H.-Y. Housing Provision and Population Concentration in the Capital Region; Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2002. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Im, J.; Kim, C. Health problem of residents in islands and solution. Korean J. Rural Med. 2002, 27, 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Cho, S.; Lee, J.; Lim, T.; Park, I.; Lee, J. Study for Standardization of Korean Triage and Acuity Scale; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2012.

- Park, J.; Lim, T. Korean triage and acuity scale (KTAS). J. Korean Soc. Emerg. Med. 2017, 28, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge, R. CAEP issues. The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale: A new and critical element in health care reform. Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. J. Emerg. Med. 1998, 16, 507–511. [Google Scholar]

- Health Publishing Inc. Urgent Degree Judgment Support, Provider Manual, CTAS 2008 Japanese Version, JTAS Prototype; Health Publishing Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 2011. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, E.H.; Lewis, R.J. (Eds.) JAMA Guide to Statistics and Methodes; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, A.; Sabin, C. Medical Statistics at a Glance; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, I.J.; Haston, W.S. Medical decision support for remote general practitioners using telemedicine. J. Telemed. Telecare 1997, 3, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, C.J. Emergency Physicians’ Roles in a Clinical Telemedicine Network. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1997, 30, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natafgi, N.; Shane, D.M.; Ullrich, F.; MacKinney, A.C.; Bell, A.; Ward, M.M. Using tele-emergency to avoid patient transfers in rural emergency departments: An assessment of costs and benefits. J. Telemed. Telecare 2018, 24, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, F.B.; Ricci, M.; Caputo, M.; Shackford, S.; Sartorelli, K.; Callas, P.; Dewell, J.; Daye, S. The use of telemedicine for real-time video consultation between trauma center and community hospital in a rural setting improves early trauma care: Preliminary results. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2001, 51, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-H.; Pong, Y.-P.; Liang, C.-C.; Lin, P.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-H. Teleconsultation by using the mobile camera phone for remote management of the extremity wound: A pilot study. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2004, 53, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oeveren, L.; Donner, J.; Fantegrossi, A.; Mohr, N.M.; Brown, I.I.I.C.A. Telemedicine-assisted intubation in rural emergency departments: A national emergency airway registry study. Telemed. E-Health 2017, 23, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total | Trauma | Non-Trauma | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Total | 2604 | 100.0 | 1038 | 100.0 | 1566 | 100.0 | ||

| Gender | <0.001 | |||||||

| Male | 1572 | 60.4 | 684 | 65.9 | 888 | 56.7 | ||

| Female | 1032 | 39.6 | 354 | 34.1 | 678 | 43.3 | ||

| Age (Years) | <0.001 | |||||||

| Mean ± SD | 61.0 ± 22.4 | 56.0 ± 23.2 | 65.0 ± 20.9 | |||||

| Region | 2604 | 1038 | 1566 | 0.320 | ||||

| Island | 73 | 2.8 | 25 | 2.4 | 48 | 3.1 | ||

| Non-Island | 2531 | 97.2 | 1013 | 97.6 | 1518 | 96.9 | ||

| Time of consultation | 2604 | 1038 | 1566 | <0.001 | ||||

| 00:00–05:59 | 339 | 13.0 | 137 | 13.2 | 202 | 12.9 | ||

| 06:00–11:59 | 506 | 19.4 | 148 | 14.3 | 358 | 22.9 | ||

| 12:00–17:59 | 848 | 32.6 | 325 | 31.3 | 523 | 33.4 | ||

| 18:00–23:59 | 911 | 35.0 | 428 | 41.2 | 483 | 30.8 | ||

| Consultation request method | 2600 | 1038 | 1562 | <0.001 | ||||

| Video | 2146 | 82.5 | 960 | 92.5 | 1186 | 75.9 | ||

| Telephone | 454 | 17.5 | 78 | 7.5 | 376 | 24.1 | ||

| Reason for Consultation | 2604 | 1038 | 1566 | <0.001 | ||||

| Procedure and Treatment Guidance | 127 | 4.9 | 29 | 2.8 | 98 | 6.3 | ||

| Image interpretation | 1421 | 54.6 | 740 | 71.3 | 681 | 43.5 | ||

| Transfer request | 1056 | 40.6 | 269 | 25.9 | 787 | 50.3 | ||

| Consultation Result | 2604 | 1038 | 1566 | <0.001 | ||||

| Transportation | 1303 | 50.0 | 407 | 39.2 | 896 | 57.2 | ||

| Admission to rural hospital | 553 | 21.2 | 211 | 20.3 | 342 | 21.8 | ||

| Discharge from rural hospital | 784 | 28.7 | 420 | 40.5 | 328 | 20.9 | ||

| Disease Severity | 2433 | 973 | 1460 | <0.001 | ||||

| KTAS * 1–2 (severe) | 782 | 32.1 | 188 | 19.3 | 594 | 40.7 | ||

| KTAS * 3–5 (mild to moderate) | 1651 | 67.8 | 785 | 80.6 | 866 | 59.4 | ||

| Reduction in Unnecessary Transportation (RUT) * | 1301 | 50.0 | 631 | 60.8 | 670 | 42.8 | <0.001 | |

| Characteristics | Total | Island | Non-Island | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Total | 2604 | 100.0 | 73 | 100.0 | 2531 | 100.0 | ||

| Time of consultation | 2604 | 73 | 2531 | 0.400 | ||||

| 00:00–05:59 | 339 | 13.0 | 10 | 13.7 | 329 | 13.0 | ||

| 06:00–11:59 | 506 | 19.4 | 19 | 26.0 | 487 | 19.2 | ||

| 12:00–17:59 | 848 | 32.6 | 24 | 32.9 | 824 | 32.6 | ||

| 18:00–23:59 | 911 | 35.0 | 20 | 27.4 | 891 | 35.2 | ||

| Reason for Consultation | 2604 | 73 | 2531 | <0.001 | ||||

| Procedure and Treatment Guidance | 127 | 4.9 | 10 | 13.7 | 117 | 4.6 | ||

| Image interpretation | 1421 | 54.6 | 18 | 24.7 | 1403 | 55.4 | ||

| Transfer request | 1056 | 40.6 | 45 | 61.6 | 1011 | 39.9 | ||

| Consultation Result | 2604 | 73 | 2531 | 0.003 | ||||

| Transportation | 1303 | 50.0 | 51 | 69.9 | 1252 | 49.5 | ||

| Admission to rural hospital | 553 | 21.2 | 10 | 13.7 | 543 | 21.5 | ||

| Discharge from rural hospital | 784 | 28.7 | 12 | 16.4 | 736 | 29.1 | ||

| Disease Severity | 2433 | 66 | 2367 | <0.001 | ||||

| KTAS * 1–2 (severe) | 782 | 32.1 | 35 | 53.0 | 747 | 31.6 | ||

| KTAS * 3–5 (mild to moderate) | 1651 | 67.8 | 31 | 47.0 | 1620 | 68.4 | ||

| Reduction in Unnecessary Transportation (RUT) * | 1301 | 50.0 | 22 | 30.1 | 1279 | 50.5 | 0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, W.; Lim, Y.; Heo, T.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.; Kim, S.-C.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; et al. Characteristics and Effectiveness of Mobile- and Web-Based Tele-Emergency Consultation System between Rural and Urban Hospitals in South Korea: A National-Wide Observation Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196252

Choi W, Lim Y, Heo T, Lee S, Kim W, Kim S-C, Kim Y, Kim J, Kim H, Kim H, et al. Characteristics and Effectiveness of Mobile- and Web-Based Tele-Emergency Consultation System between Rural and Urban Hospitals in South Korea: A National-Wide Observation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(19):6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196252

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, WooSung, YongSu Lim, Tag Heo, SungMin Lee, Won Kim, Sang-Chul Kim, YeonWoo Kim, JaeHyuk Kim, Hyun Kim, HyungIl Kim, and et al. 2023. "Characteristics and Effectiveness of Mobile- and Web-Based Tele-Emergency Consultation System between Rural and Urban Hospitals in South Korea: A National-Wide Observation Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 19: 6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196252

APA StyleChoi, W., Lim, Y., Heo, T., Lee, S., Kim, W., Kim, S.-C., Kim, Y., Kim, J., Kim, H., Kim, H., Lee, T., & Kim, C. (2023). Characteristics and Effectiveness of Mobile- and Web-Based Tele-Emergency Consultation System between Rural and Urban Hospitals in South Korea: A National-Wide Observation Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(19), 6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12196252