Patients with Clinically Suspected Gallstone Disease: A More Selective Ultrasound May Improve Treatment Related Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Gallstones were not found on US in two-thirds of patients referred for a suspicion of gallstone disease.

- -

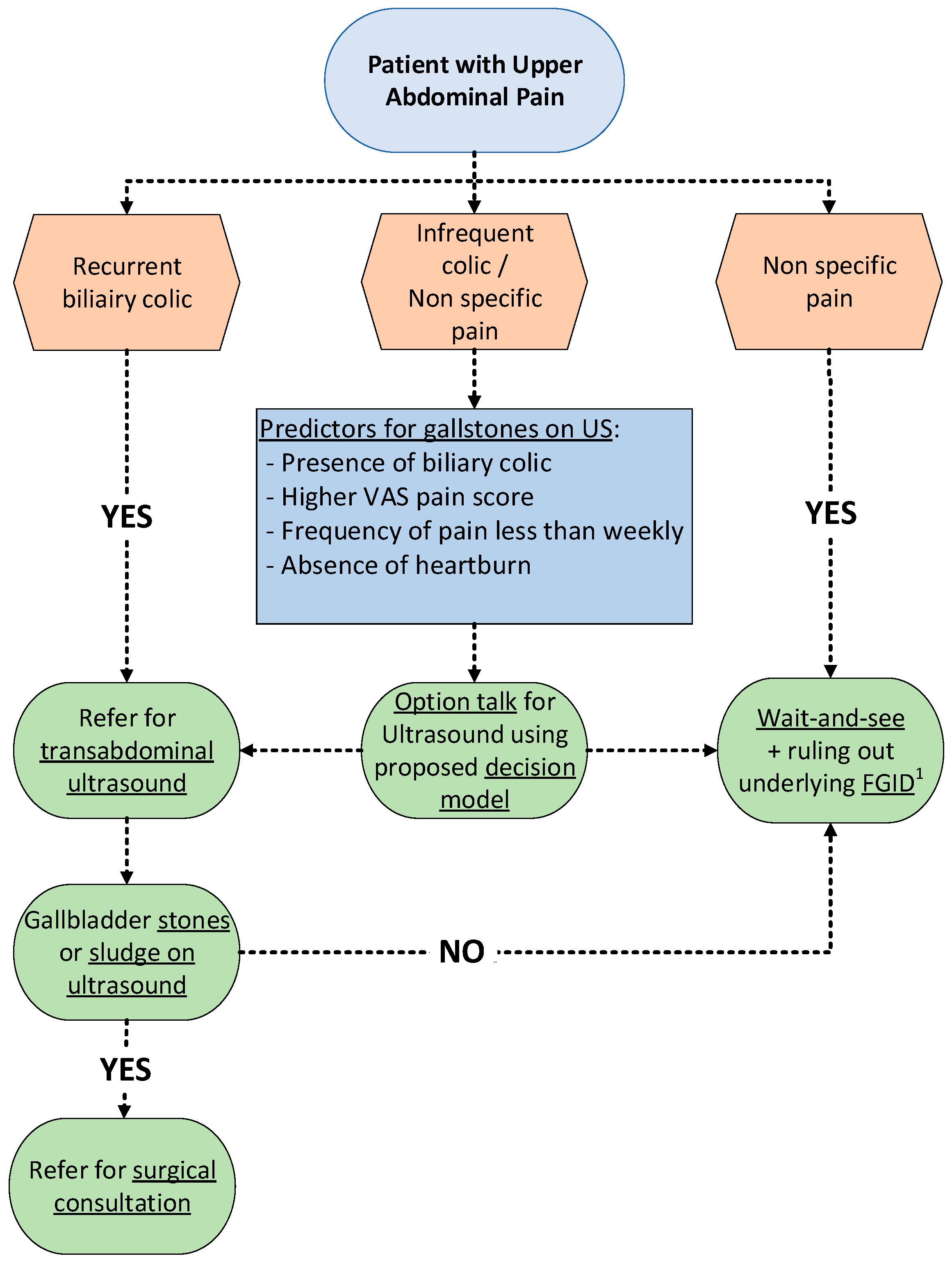

- Variables associated with gallstones were biliary colic, more severe pain, frequency of pain less than weekly, and an absence of heartburn.

- -

- A prediction model may aid the GP in the selection of patients for US in case of suspicion of gallstones.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

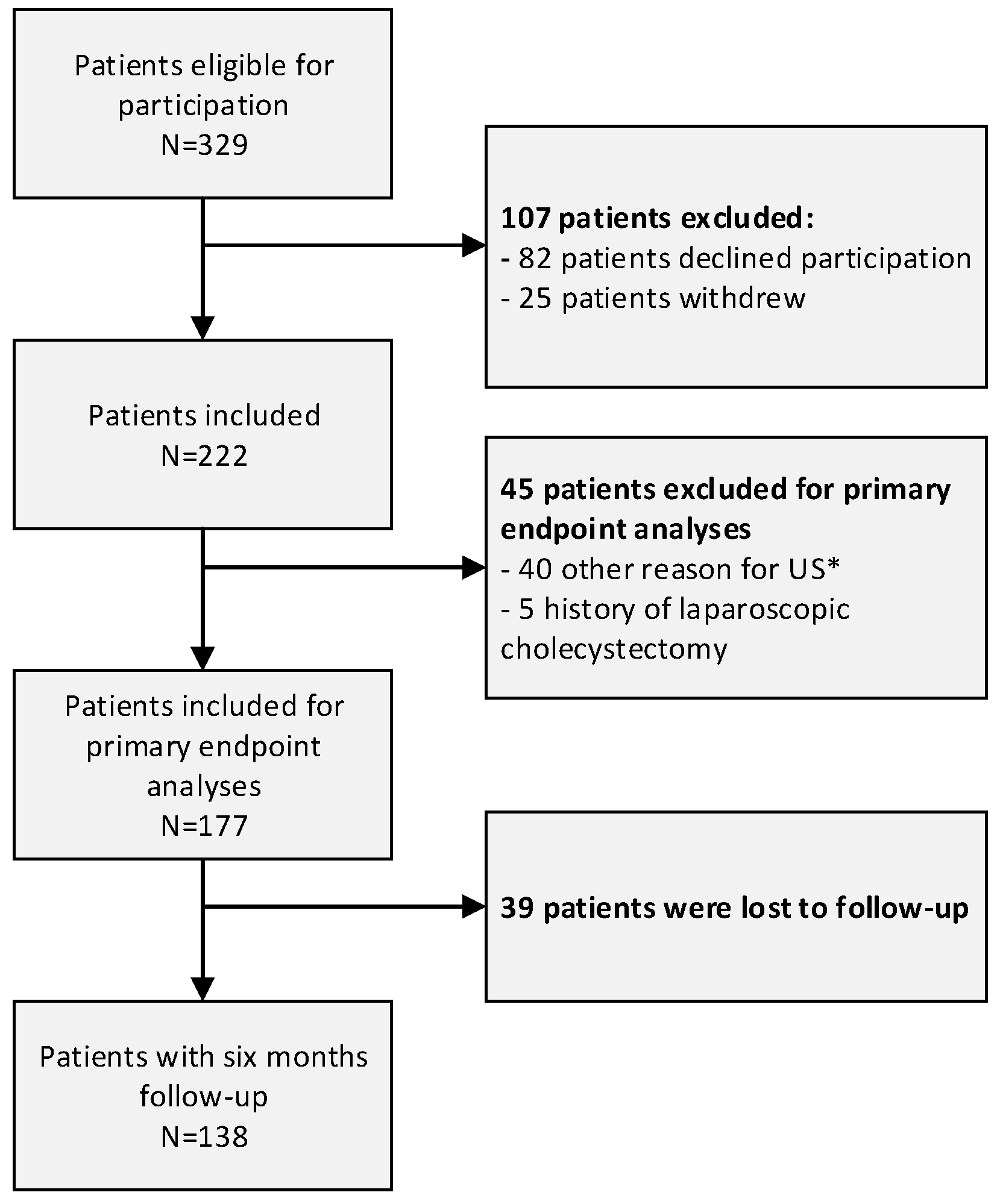

2.2. Recruitment and Selection of Study Subjects

2.3. Measurements

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient’s Characteristics

3.2. Confirmation of Gallstones on Ultrasound in Patients with Clinical Suspicion of Gallstone Disease

3.3. Comparison of Patients with and without Gallstones

3.4. Prediction Model

3.5. Outcomes at Six Months’ Follow-Up

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.4. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Portincasa, P.; Moschetta, A.; Palasciano, G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet 2006, 368, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutch Society of Surgery. Dutch Society of Surgery Evidence-Based Guideline. Diagnostic and Treatment of Gallstones; Dutch Society of Surgery: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Association for the Study Of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 146–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overby, D.W.; Apelgren, K.N.; Richardson, W.; Fanelli, R. SAGES guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Surg. Endosc. 2010, 24, 2368–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammert, F.; Gurusamy, K.; Ko, C.W.; Miquel, J.F.; Mendez-Sanchez, N.; Portincasa, P.; van Erpecum, K.J.; van Laarhoven, C.; Wang, D.Q.H. Gallstones. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutch Healthcare Authority: Data on Healthcare Utilization. 2017. Available online: https://www.opendisdata.nl/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Latenstein, C.S.; Wennmacker, S.Z.; Groenewoud, S.; Noordenbos, M.W.; Atsma, F.; de Reuver, P.R. Hospital Variation in Cholecystectomies in The Netherlands: A Nationwide Observational Study. Dig. Surg. 2020, 37, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rome Group for Epidemiology and Prevention of Cholelithiasis (GREPCO). The epidemiology of gallstone disease in Rome, Italy. Part II. Factors associated with the disease. The Rome Group for Epidemiology and Prevention of Cholelithiasis (GREPCO). Hepatology 1988, 8, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, A.H.; Wennmacker, S.Z.; de Reuver, P.R.; Latenstein, C.S.S.; Buyne, O.; Donkervoort, S.C.; Eijsbouts, Q.A.J.; Heisterkamp, J.; Hof, K.H.I.H.; Janssen, J.; et al. Restrictive strategy versus usual care for cholecystectomy in patients with gallstones and abdominal pain (SECURE): A multicentre, randomised, parallel-arm, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 2322–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, J.J.; Latenstein, C.S.S.; Boerma, D.; Hazebroek, E.J.; Hirsch, D.; Heikens, J.T.; Konsten, J.; Polat, F.; Lantinga, M.A.; van Laarhoven, C.J.H.M.; et al. Functional Dyspepsia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome are Highly Prevalent in Patients with Gallstones and are Negatively Associated with Outcomes After Cholecystectomy: A Prospective, Multicentre, Observational Study (PERFECT-Trial). Ann. Surg. 2020, 275, e766–e772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunnissen, F.M.; Drager, L.D.; Braak, B.; Drenth, J.P.H.; van Laarhoven, C.J.H.M.; Schers, H.J.; de Reuver, P.R. Healthcare utilisation of patients with cholecystolithiasis in primary care: A multipractice comparative analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e053188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Del Mar, C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: A systemat-ic review. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speets, A.M.; Kalmijn, S.; Hoes, A.W.; Van Der Graaf, Y.; Mali, W.P.T.M. Yield of abdominal ultrasound in patients with abdominal pain referred by general practitioners. Eur. J. Gen. Pr. 2006, 12, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloechle, C.; Izbicki, J.R.; Knoefel, W.T.; Kuechler, T.; Broelsch, C.E. Quality of life in chronic pancreatitis--results after duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas. Pancreas 1995, 11, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Smeden, M.; Moons, K.G.; de Groot, J.A.; Collins, G.S.; Altman, D.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Reitsma, J.B. Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Stat. Methods Med Res. 2019, 28, 2455–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latenstein, C.S.S.; Hannink, G.; van der Bilt, J.D.W.; Donkervoort, S.C.; Eijsbouts, Q.A.J.; Heisterkamp, J.; Nieuwenhuijs, V.B.; Schreinemakers, J.M.J.; Wiering, B.; Boermeester, M.A.; et al. A Clinical Decision Tool for Selection of Patients With Symptomatic Cholelithiasis for Cholecystectomy Based on Reduction of Pain and a Pain-Free State Following Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2021, 156, e213706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Kim, J.K. Asymptotic theory and inference of predictive mean matching imputation using a superpopulation model framework. Scand Stat. Theory Appl. 2019, 47, 839–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, R.D.; Ensor, J.; Snell, K.I.; Harrell, F.E.; Martin, G.P.; Reitsma, J.B.; Moons, K.G.M.; Collins, G.; van Smeden, M. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 2020, 368, m441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moons, K.G.M.; de Groot, J.A.H.; Bouwmeester, W.; Vergouwe, Y.; Mallett, S.; Altman, D.G.; Reitsma, J.B.; Collins, G.S. Critical Appraisal and Data Extraction for Systematic Reviews of Prediction Modelling Studies: The CHARMS Checklist. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, M.; Ambler, G.; Seaman, S.; De Iorio, M.; Omar, R.Z. Review and evaluation of penalised regression methods for risk prediction in low-dimensional data with few events. Stat. Med. 2015, 35, 1159–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, M.; Ambler, G.; Seaman, S.R.; Guttmann, O.; Elliott, P.; King, M.; Omar, R.Z. How to develop a more accurate risk prediction model when there are few events. BMJ 2015, 351, h3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, M.Y.; Hartman, T.C.O.; Velden, J.J.I.M.V.D.; Bohnen, A.M. Is biliary pain exclusively related to gallbladder stones? A controlled prospective study. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2004, 54, 574–579. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.Y.; Van Der Velden, J.J.; Lijmer, J.G.; De Kort, H.; Prins, A.; Bohnen, A.M. Abdominal symptoms: Do they predict gallstones? A systematic review. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 35, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thistle, J.L.; Longstreth, G.F.; Romero, Y.; Arora, A.S.; Simonson, J.A.; Diehl, N.N.; Harmsen, W.S.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Factors That Predict Relief From Upper Abdominal Pain After Cholecystectomy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 9, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouwel, F.; Meurs-Szojda, M.M.; Klemt-Kropp, M.; Fockens, P.; Grasman, M.E. The diagnostic yield of open-access endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the Netherlands. Endosc. Int. Open 2018, 06, E383–E394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (N = 177) | Gallstones (N = 64) | Absence of Gallstones (N = 113) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 54.8 (15.4) | 56.1 (14.8) | 53.8 (16.0) | 0.384 |

| Sex, Female n (%) | 119 (67.2) | 46 (71.9) | 73 (64.6) | 0.322 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.8 (4.7) | 27.2 (4.3) | 26.5 (4.9) | 0.354 |

| Consumes alcohol, n (%) | 126 (71.2) | 44 (68.8) | 82 (72.6) | 0.590 |

| Current smoker, n (%) ^ | 28 (15.8) | 4 (6.3) | 24 (21.2) | 0.009 |

| Abdominal surgery in history, n (%) | 51 (28.8) | 18 (28.1) | 33 (29.2) | 0.879 |

| Abdominal pain | ||||

| Izbicki Pain Score, median (IQR) | 32.5 (26.9–40.0) | 31.2 (26.8–37.6) | 33.7 (26.8–42.0) | 0.185 |

| VAS pain score, median (IQR) | 7.0 (4.0–8.0) | 8.0 (5.5–9.0) | 6.0 (4.0–7.5) | p < 0.001 |

| Biliary symptoms * | ||||

| Severe pain attacks, n (%) | 128 (72.3) | 50 (78.1) | 78 (69.0) | 0.194 |

| Pain in right upper quadrant/epigastric region, n (%) | 148 (83.6) | 55 (85.9) | 93 (82.3) | 0.530 |

| Duration of pain longer than 15–30 min, n (%) * | 137 (77.4) | 56 (87.5) | 81 (71.7) | 0.020 |

| Biliary colic, n (%) * | 90 (50.8) | 40 (62.5) | 50 (44.2) | 0.023 |

| Pain radiating to the back, n (%) | 96 (54.2) | 36 (56.3) | 60 (53.1) | 0.686 |

| Use of pain medication, n (%) | 74 (41.8) | 36 (56.3) | 38 (33.6) | 0.003 |

| Urge to move, n (%) β | 45 (25.4) | 15 (23.4) | 30 (26.5) | 0.998 |

| Weekly pain, n (%) β | 76 (42.9) | 14 (21.9) | 62 (54.9) | p < 0.001 |

| Functional symptoms β | ||||

| Difficult defecation, n (%) # | 14 (7.9) | 1 (1.6) | 13 (11.5) | 0.026 |

| Diarrhoea, n (%) β | 12 (6.8) | 3 (4.7) | 9 (8.0) | 0.495 |

| Heartburn, n (%) β | 17 (9.6) | 3 (4.7) | 14 (12.4) | 0.133 |

| Abdominal bloating, n (%) β | 30 (16.9) | 5 (7.8) | 25 (22.1) | 0.026 |

| Nausea/Vomitus, n (%) | 15 (8.5) | 6 (9.4) | 9 (8.0) | 0.604 |

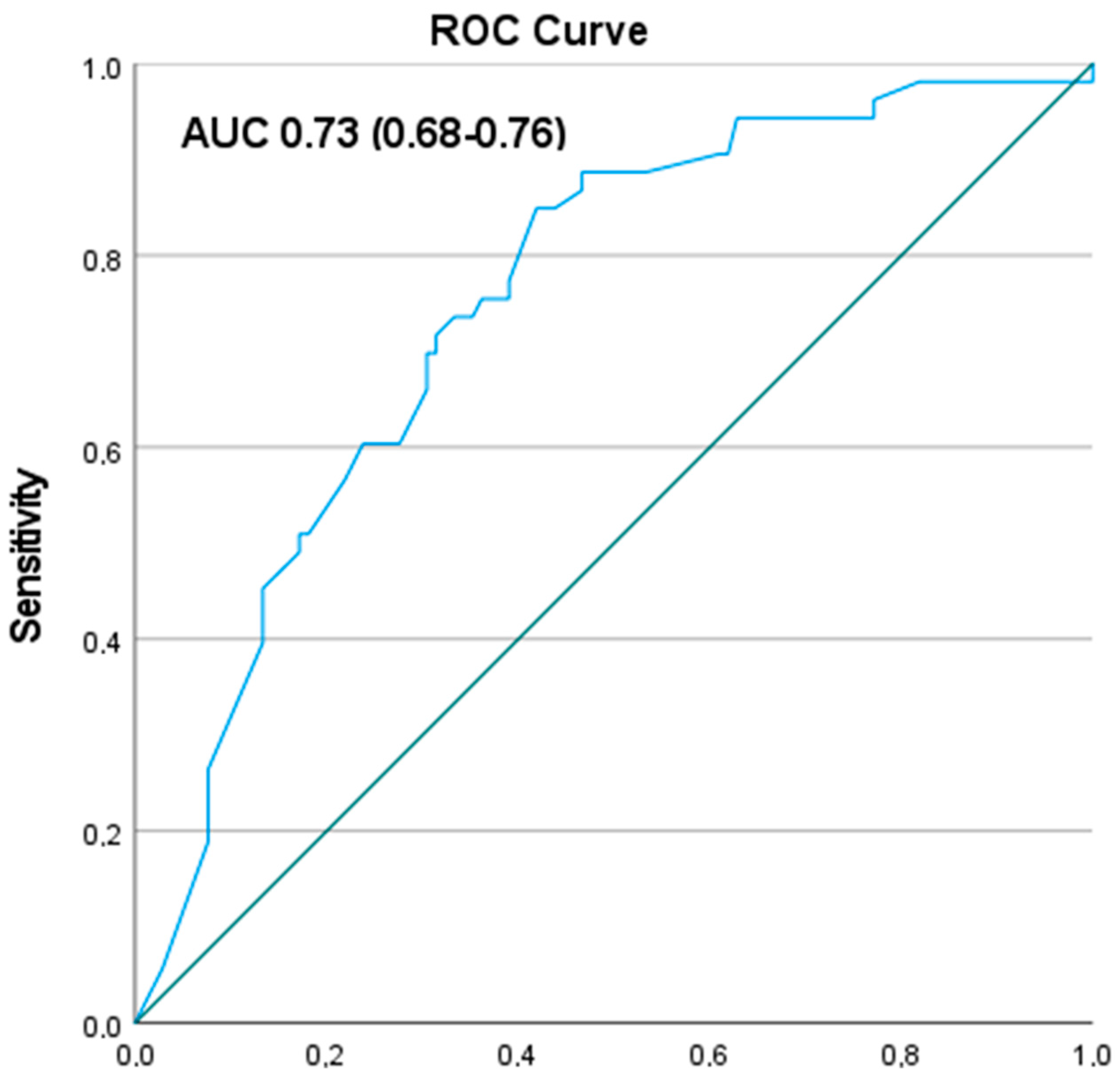

| Predictors | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Intercept | |

| Presence of biliary colic according to ROME criteria & | |

| No | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1.36 (0.63–2.92) |

| VAS pain score squared * | |

| No pain | 1 [Reference] |

| Per step | 1.05 (0.99–1.11) |

| Heartburn | |

| No | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.61 (0.12–3.08) |

| Frequency of pain is weekly | |

| No | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 0.35 (0.15–0.83) |

| AUC | 0.73 (0.68–0.76) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thunnissen, F.M.; Comes, D.J.; Geenen, R.W.F.; Riviere, D.; Latenstein, C.S.S.; Lantinga, M.A.; Schers, H.J.; van Laarhoven, C.J.H.M.; Drenth, J.P.H.; Atsma, F.; et al. Patients with Clinically Suspected Gallstone Disease: A More Selective Ultrasound May Improve Treatment Related Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124162

Thunnissen FM, Comes DJ, Geenen RWF, Riviere D, Latenstein CSS, Lantinga MA, Schers HJ, van Laarhoven CJHM, Drenth JPH, Atsma F, et al. Patients with Clinically Suspected Gallstone Disease: A More Selective Ultrasound May Improve Treatment Related Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(12):4162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124162

Chicago/Turabian StyleThunnissen, Floris M., Daan J. Comes, Remy W. F. Geenen, Deniece Riviere, Carmen S. S. Latenstein, Marten A. Lantinga, Henk J. Schers, Cornelis J. H. M. van Laarhoven, Joost P. H. Drenth, Femke Atsma, and et al. 2023. "Patients with Clinically Suspected Gallstone Disease: A More Selective Ultrasound May Improve Treatment Related Outcomes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 12: 4162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124162

APA StyleThunnissen, F. M., Comes, D. J., Geenen, R. W. F., Riviere, D., Latenstein, C. S. S., Lantinga, M. A., Schers, H. J., van Laarhoven, C. J. H. M., Drenth, J. P. H., Atsma, F., & de Reuver, P. R. (2023). Patients with Clinically Suspected Gallstone Disease: A More Selective Ultrasound May Improve Treatment Related Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(12), 4162. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12124162