A Tailored Antithrombotic Approach for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndrome and/or Undergoing PCI: A Case Series

Abstract

:1. Introduction

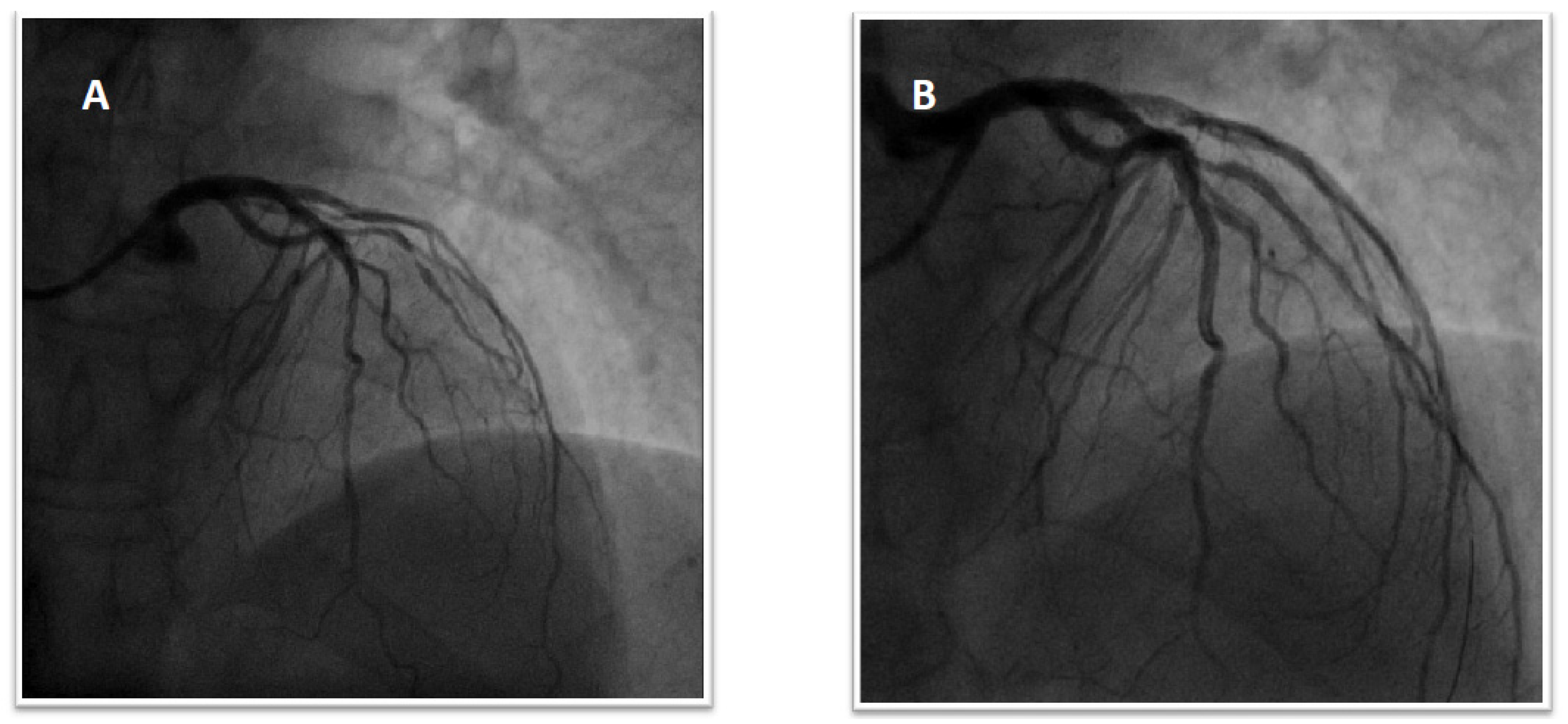

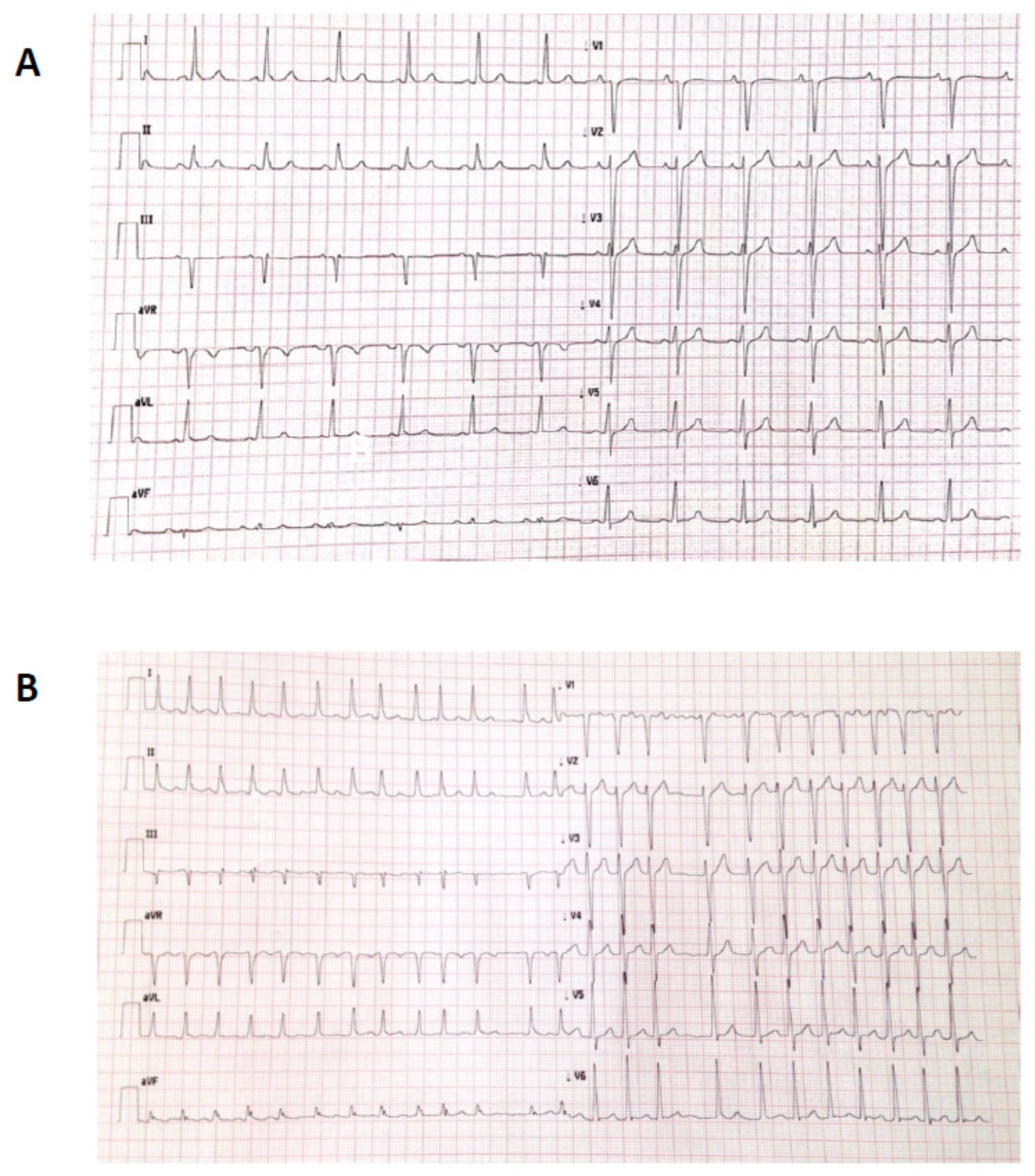

1.1. Patient 1

1.2. Patient 2

1.3. Patient 3

1.4. Patient 4

1.5. Patient 5

2. Discussion

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumbhani, D.J.; Cannon, C.P.; Beavers, C.J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Cuker, A.; Gluckman, T.J.; Marine, J.E.; Mehran, R.; Messe, S.R.; Patel, N.S.; et al. 2020 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway for Anticoagulant and Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation or Venous Thromboembolism Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solu-tion Set Oversight Committee. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 77, 629–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwlaat, R.; Capucci, A.; Camm, A.J.; Olsson, S.B.; Andresen, D.; Davies, D.W.; Cobbe, S.; Breithardt, G.; Le Heuzey, J.-Y.; Prins, M.H.; et al. Atrial fibrillation management: A prospective survey in ESC Member Countries: The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 2422–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Rein, N.; Heide-Jørgensen, U.; Lijfering, W.M.; Dekkers, O.M.; Sørensen, H.T.; Cannegieter, S.C. Major Bleeding Rates in Atrial Fibrillation Patients on Single, Dual, or Triple Antithrombotic Therapy. Circulation 2019, 139, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargiulo, G.; Goette, A.; Tijssen, J.; Eckardt, L.; Lewalter, T.; Vranckx, P.; Valgimigli, M. Safety and efficacy outcomes of double vs. triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation following percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant-based randomized clinical trials. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3757–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Potpara, T.S.; Mujovic, N.; Proietti, M.; Dagres, N.; Hindricks, G.; Collet, J.-P.; Valgimigli, M.; Heidbuchel, H.; Lip, G.Y.H. Revisiting the effects of omitting aspirin in combined antithrombotic therapies for atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndromes or percutaneous coronary interventions: Meta-analysis of pooled data from the PIONEER AF-PCI, RE-DUAL PCI, and AUGUSTUS trials. Europace 2020, 22, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindricks, G.; Potpara, T.; Dagres, N.; Arbelo, E.; Bax, J.J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Boriani, G.; Castella, M.; Dan, G.-A.; Dilaveris, P.E.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 373–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiolillo, D.J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Cannon, C.P.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Gibson, C.M.; Goodman, S.G.; Granger, C.B.; Holmes, D.R.; Lopes, R.D.; Mehran, R.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Treated With Oral Anticoagulation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A North American Perspective: 2021 Update. Circulation 2021, 143, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Harrington, R.; Stone, G.; Steg, G.; Gibson, C.; Hamm, C.; Price, M.; Lopes, R.; Leonardi, S.; Deliargyris, E.; et al. Short- and long-term mortality following bleeding events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: Insights from four validated bleeding scales in the CHAMPION trials. EuroIntervention 2018, 13, e1841–e1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.M.; Mehran, R.; Bode, C.; Halperin, J.; Verheugt, F.W.; Wildgoose, P.; Birmingham, M.; Ianus, J.; Burton, P.; van Eickels, M.; et al. Prevention of Bleeding in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing PCI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2423–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lopes, R.D.; Heizer, G.; Aronson, R.; Vora, A.N.; Massaro, T.; Mehran, R.; Goodman, S.G.; Windecker, S.; Darius, H.; Li, J.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndrome or PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1509–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vranckx, P.; Valgimigli, M.; Eckardt, L.; Tijssen, J.; Lewalter, T.; Gargiulo, G.; Batushkin, V.; Campo, G.; Lysak, Z.; Vakaliuk, I.; et al. Edoxaban-based versus vitamin K antagonist-based antithrombotic regimen after successful coronary stenting in patients with atrial fibrillation (ENTRUST-AF PCI): A randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, C.P.; Bhatt, D.L.; Oldgren, J.; Lip, G.Y.; Ellis, S.G.; Kimura, T.; Maeng, M.; Merkely, B.; Zeymer, U.; Gropper, S.; et al. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran after PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.D.; Hong, H.; Harskamp, R.E.; Bhatt, D.L.; Mehran, R.; Cannon, C.P.; Granger, C.B.; Verheugt, F.W.A.; Li, J.; Berg, J.M.T.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Antithrombotic Strategies in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vranckx, P.; Lewalter, T.; Valgimigli, M.; Tijssen, J.G.; Reimitz, P.-E.; Eckardt, L.; Lanz, H.-J.; Zierhut, W.; Smolnik, R.; Goette, A. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of an edoxaban-based antithrombotic regimen in patients with atrial fibrillation following successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent placement: Rationale and design of the ENTRUST-AF PCI trial. Am. Heart J. 2018, 196, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.U.; Osman, M.; Khan, M.U.; Zhao, D.; Mamas, M.A.; Savji, N.; Al-Abdouh, A.; Hasan, R.K.; Michos, E.D. Dual Versus Triple Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, G.; Cannon, C.P.; Gibson, C.M.; Goette, A.; Lopes, R.D.; Oldgren, J.; Korjian, S.; Windecker, S.; Esposito, G.; Vranckx, P.; et al. Safety and efficacy of double vs. triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation with or without acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A collaborative meta-analysis of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant-based randomized clinical trials. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2021, 7, f50–f60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffel, J.; Collins, R.; Antz, M.; Cornu, P.; Desteghe, L.; Haeusler, K.G.; Oldgren, J.; Reinecke, H.; Roldan-Schilling, V.; Rowell, N.; et al. 2021 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the Use of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Europace 2021, 23, 1612–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, I.; Briasoulis, A.; Pappas, C.; Ikonomidis, I.; Alexopoulos, D. Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel as Part of Dual or Triple Antithrombotic Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2018, 32, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Singh, K.; Abunassar, J.; Malhotra, N.; Le May, M.; Labinaz, M.; Glover, C.; Marquis, J.-F.; Froeschl, M.; Dick, A.; et al. Ticagrelor in Triple Antithrombotic Therapy: Predictors of Ischemic and Bleeding Complications. Clin. Cardiol. 2016, 39, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.R.; Ju, C.; Zettler, M.; Messenger, J.C.; Cohen, D.J.; Stone, G.W.; Baker, B.A.; Effron, M.B.; Peterson, E.D.; Wang, T.Y. Outcomes of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Receiving an Oral Anticoagulant and Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: A Comparison of Clopidogrel Versus Prasugrel From the TRANSLATE-ACS Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarafoff, N.; Martischnig, A.; Wealer, J.; Mayer, K.; Mehilli, J.; Sibbing, D.; Kastrati, A. Triple Therapy With Aspirin, Prasugrel, and Vitamin K Antagonists in Patients With Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation and an Indication for Oral Anticoagulation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 2060–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verlinden, N.; Coons, J.C.; Iasella, C.J.; Kane-Gill, S.L. Triple Antithrombotic Therapy With Aspirin, P2Y12 Inhibitor, and Warfarin After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: An Evaluation of Prasugrel or Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 22, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collet, J.-P.; Thiele, H.; Barbato, E.; Barthélémy, O.; Bauersachs, J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Dendale, P.; Dorobantu, M.; Edvardsen, T.; Folliguet, T.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1289–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, S.; Kaikita, K.; Akao, M.; Ako, J.; Matoba, T.; Nakamura, M.; Miyauchi, K.; Hagiwara, N.; Kimura, K.; Hirayama, A.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation with Stable Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windecker, S.; Lopes, R.D.; Massaro, T.; Jones-Burton, C.; Granger, C.B.; Aronson, R.; Heizer, G.; Goodman, S.G.; Darius, H.; Jones, W.S.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Acute Coronary Syndrome Treated Medically or With Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or Undergoing Elective Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Insights From the AUGUSTUS Trial. Circulation 2019, 140, 1921–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldgren, J.; Steg, P.G.; Hohnloser, S.H.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Kimura, T.; Nordaby, M.; Brueckmann, M.; Kleine, E.; Berg, J.M.T.; Bhatt, D.L.; et al. Dabigatran dual therapy with ticagrelor or clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention in atrial fibrillation patients with or without acute coronary syndrome: A subgroup analysis from the RE-DUAL PCI trial. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giubilato, S.; Lucà, F.; Pozzi, A.; Caretta, G.; Cornara, S.; Pilleri, A.; Di Nora, C.; Amico, F.; Di Matteo, I.; Favilli, S.; et al. A Tailored Antithrombotic Approach for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndrome and/or Undergoing PCI: A Case Series. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11144089

Giubilato S, Lucà F, Pozzi A, Caretta G, Cornara S, Pilleri A, Di Nora C, Amico F, Di Matteo I, Favilli S, et al. A Tailored Antithrombotic Approach for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndrome and/or Undergoing PCI: A Case Series. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022; 11(14):4089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11144089

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiubilato, Simona, Fabiana Lucà, Andrea Pozzi, Giorgio Caretta, Stefano Cornara, Anna Pilleri, Concetta Di Nora, Francesco Amico, Irene Di Matteo, Silvia Favilli, and et al. 2022. "A Tailored Antithrombotic Approach for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndrome and/or Undergoing PCI: A Case Series" Journal of Clinical Medicine 11, no. 14: 4089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11144089

APA StyleGiubilato, S., Lucà, F., Pozzi, A., Caretta, G., Cornara, S., Pilleri, A., Di Nora, C., Amico, F., Di Matteo, I., Favilli, S., Rossini, R., Riccio, C., Colivicchi, F., & Gulizia, M. M., on behalf of Management and Quality Working Group ANMCO. (2022). A Tailored Antithrombotic Approach for Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Presenting with Acute Coronary Syndrome and/or Undergoing PCI: A Case Series. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(14), 4089. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11144089