Achalasia in the Elderly: Diagnostic Approach and a Proposed Treatment Algorithm Based on a Comprehensive Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Diagnostic Approach to Esophageal Dysphagia and Achalasia in the Elderly

2. Treatment Options

2.1. Endoscopic Treatment

2.1.1. Botulinum Toxin

2.1.2. Pneumatic Dilation

2.1.3. Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM)

3. Surgical Treatment

Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy in Elderly Patients

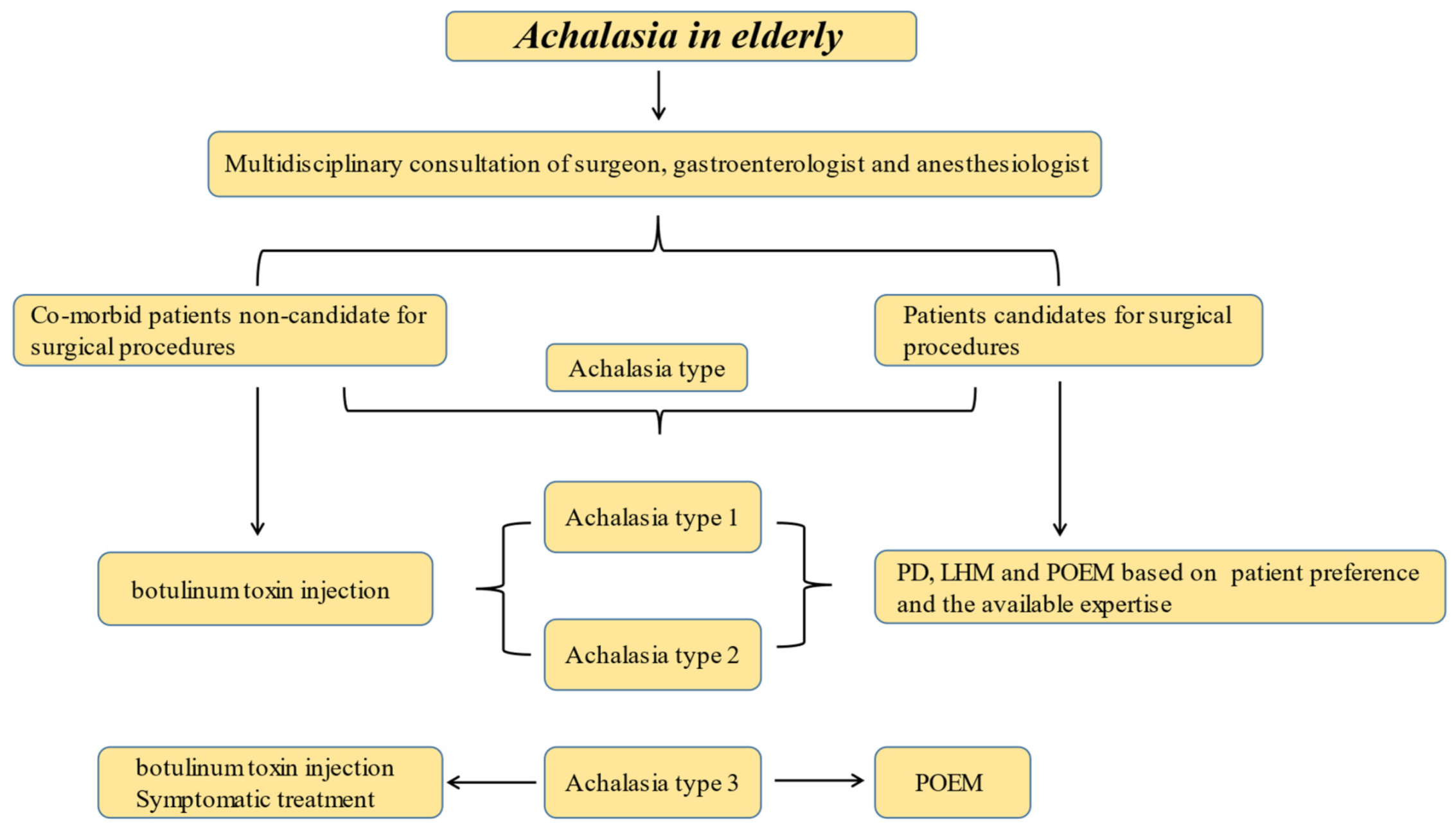

4. Conclusions and a Proposed Approach

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LES | Lower esophageal sphincter |

| EGJ | Esophago-gastric junction |

| EGJOO | Esophago-gastric outflow obstruction |

| HRM | High-resolution manometry |

| POEM | Per oral endoscopic myotomy |

| EoE | Eosinophilic esophagitis |

| EGD | Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy |

| LHM | Laparoscopic Heller myotomy |

| RDC | Rapid drinking challenge |

| MRS | Multiple rapid swallows |

| TBS | Timed barium swallow |

References

- Gockel, I.; Becker, J.; Wouters, M.M.; Niebisch, S.; Gockel, H.R.; Hess, T.; Ramonet, D.; Zimmermann, J.; Vigo, A.G.; Trynka, G.; et al. Common variants in the HLA-DQ region confer susceptibility to idiopathic achalasia. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, V.F.; Hoischen, T.; Bernhard, G. Life expectancy, complications, and causes of death in patients with achalasia: Results of a 33-year follow-up investigation. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 20, 956–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennaro, N.; Portale, G.; Gallo, C.; Rocchietto, S.; Caruso, V.; Costantini, M.; Salvador, R.; Ruol, A.; Zaninotto, G. Esophageal achalasia in the Veneto region: Epidemiology and treatment. Epidemiology and treatment of achalasia. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2011, 15, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumic, I.; Nordin, T.; Jecmenica, M.; Stojkovic Lalosevic, M.; Milosavljevic, T.; Milovanovic, T. Gastrointestinal Tract Disorders in Older Age. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 2019, 6757524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasch, H.; Castell, D.O.; Castell, J.A. Evidence for diminished visceral pain with aging: Studies using graded intraesophageal balloon distension. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 272, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemme, E.M.; Domingues, G.R.; Pereira, V.L.; Firman, C.G.; Pantoja, J. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure in idiopathic achalasia and Chagas disease-related achalasia. Dis. Esophagus 2001, 14, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, W.C.; Chen, C.L. Aging and neural control of the GI tract: IV Clinical and physiological aspects of gastrointestinal motility and aging. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 2002, 283, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.S.; Rao, S.S. Biomechanical and sensory parameters of the human esophagus at four levels. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 275, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouse, R.E.; Abramson, B.K.; Todorczuk, J.R. Achalasia in the elderly. Effects of aging on clinical presentation and outcome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1991, 36, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schechter, R.B.; Lemme, E.M.; Novais, P.; Biccas, B. Achalasia in the elderly patient: A comparative study. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2011, 48, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- O’Neill, O.M.; Johnston, B.T.; Coleman, H.G. Achalasia: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 5806–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninotto, G.; Bennett, C.; Boeckxstaens, G.; Costantini, M.; Ferguson, M.K.; Pandolfino, J.E.; Patti, M.G.; Ribeiro, U., Jr.; Richter, J.; Swanstrom, L.; et al. The 2018 ISDE achalasia guidelines. Dis. Esophagus 2018, 31, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadlapati, R.; Kahrilas, P.J.; Fox, M.R.; Bredenoord, A.J.; Prakash Gyawali, C.; Roman, S.; Babaei, A.; Mittal, R.K.; Rommel, N.; Savarino, E.; et al. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0((c)). Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e14058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, D.; Hollenstein, M.; Misselwitz, B.; Knowles, K.; Wright, J.; Tucker, E.; Sweis, R.; Fox, M. Rapid Drink Challenge in high-resolution manometry: An adjunctive test for detection of esophageal motility disorders. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29, e12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohof, W.O.; Lei, A.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. Esophageal stasis on a timed barium esophagogram predicts recurrent symptoms in patients with long-standing achalasia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanagapalli, S.; Plumb, A.; Maynard, J.; Leong, R.W.; Sweis, R. The timed barium swallow and its relationship to symptoms in achalasia: Analysis of surface area and emptying rate. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2020, 32, e13928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.A.; Kahrilas, P.J.; Lin, Z.; Hirano, I.; Gonsalves, N.; Listernick, Z.; Ritter, K.; Tye, M.; Ponds, F.A.; Wong, I.; et al. Evaluation of Esophageal Motility Utilizing the Functional Lumen Imaging Probe. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 1726–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeckxstaens, G.E.; Zaninotto, G.; Richter, J.E. Achalasia. Lancet 2014, 383, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappell, M.S.; Stavropoulos, S.N.; Friedel, D. Updated Systematic Review of Achalasia, with a Focus on POEM Therapy. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020, 65, 38–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enestvedt, B.K.; Williams, J.L.; Sonnenberg, A. Epidemiology and practice patterns of achalasia in a large multi-centre database. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoeij, F.B.; Tack, J.F.; Pandolfino, J.E.; Sternbach, J.M.; Roman, S.; Smout, A.J.; Bredenoord, A.J. Complications of botulinum toxin injections for treatment of esophageal motility disordersdagger. Dis. Esophagus 2017, 30, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M.F.; Felix, V.N.; Penagini, R.; Mauro, A.; de Moura, E.G.; Pu, L.Z.; Martinek, J.; Rieder, E. Achalasia: From diagnosis to management. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1381, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassri, A.; Ramzan, Z. Pharmacotherapy for the management of achalasia: Current status, challenges and future directions. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 6, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, P.J.; Rai, R.; Ravich, W.J.; Hendrix, T.R.; Kalloo, A.N. Botulinum toxin for achalasia: Long-term outcome and predictors of response. Gastroenterology 1996, 110, 1410–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mari, A.; Patel, K.; Mahamid, M.; Khoury, T.; Pesce, M. Achalasia: Insights into Diagnostic and Therapeutic Advances for an Ancient Disease. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markar, S.; Zaninotto, G. Endoscopic Pneumatic Dilation for Esophageal Achalasia. Am. Surg. 2018, 84, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzka, D.A.; Castell, D.O. Review article: An analysis of the efficacy, perforation rates and methods used in pneumatic dilation for achalasia. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 34, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M.F.; Richter, J.E. Current therapies for achalasia: Comparison and efficacy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1998, 27, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.R.; Coupland, B.; Mytton, J.; Evison, F.; Patel, P.; Trudgill, N.J. Outcomes of pneumatic dilatation and Heller’s myotomy for achalasia in England between 2005 and 2016. Gut 2019, 68, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zotti, O.R.; Herbella, F.A.M.; Armijo, P.R.; Oleynikov, D.; Aquino, J.L.; Leandro-Merhi, V.A.; Velanovich, V.; Salvador, R.; Costantini, M.; Low, D.; et al. Achalasia Treatment in Patients over 80 Years of Age: A Multicenter Survey. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2020, 30, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Minami, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Sato, Y.; Kaga, M.; Suzuki, M.; Satodate, H.; Odaka, N.; Itoh, H.; Kudo, S. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia. Endoscopy 2010, 42, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, Z.; Ramchandani, M.; Reddy, D.N.; Darisetty, S.; Kotla, R.; Kalapala, R.; Chavan, R. Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy in Children with Achalasia Cardia. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 22, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Tan, Y.Y.; Wang, X.H.; Liu, D.L. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for achalasia in patients aged >/= 65 years. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 9175–9181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Ren, Y.; Gao, Q.; Huang, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Wei, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, B.; et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy is safe and effective in achalasia patients aged older than 60 years compared with younger patients. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 2407–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tan, Y.; Lv, L.; Zhu, H.; Chu, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, D. Peroral endoscopic myotomy versus pneumatic dilation for achalasia in patients aged >/= 65 years. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2016, 108, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Shiwaku, H.; Inoue, H.; Sato, H.; Onimaru, M.; Minami, H.; Tanaka, S.; Sato, C.; Ogawa, R.; Okushima, N.; Yokomichi, H.; et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy for achalasia: A prospective multicenter study in Japan. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evensen, H.; Kristensen, V.; Larssen, L.; Sandstad, O.; Hauge, T.; Medhus, A.W. Outcome of peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) in treatment-naive patients. A systematic review. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khashab, M.A.; Sanaei, O.; Rivory, J.; Eleftheriadis, N.; Chiu, P.W.Y.; Shiwaku, H.; Ogihara, K.; Ismail, A.; Abusamaan, M.S.; El Zein, M.H.; et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy: Anterior versus posterior approach: A randomized single-blinded clinical trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichkhanian, Y.; Abimansour, J.P.; Pioche, M.; Vosoughi, K.; Eleftheriadis, N.; Chiu, P.W.Y.; Minami, H.; Ogihara, K.; Sanaei, O.; Jovani, M.; et al. Outcomes of anterior versus posterior peroral endoscopic myotomy 2 years post-procedure: Prospective follow-up results from a randomized clinical trial. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Lv, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Chu, Y.; Luo, M.; Li, C.; Zhou, H.; Huo, J.; Liu, D. Efficacy of anterior versus posterior per-oral endoscopic myotomy for treating achalasia: A randomized, prospective study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 88, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponds, F.A.; Fockens, P.; Lei, A.; Neuhaus, H.; Beyna, T.; Kandler, J.; Frieling, T.; Chiu, P.W.Y.; Wu, J.C.Y.; Wong, V.W.Y.; et al. Effect of Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy vs Pneumatic Dilation on Symptom Severity and Treatment Outcomes Among Treatment-Naive Patients with Achalasia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 322, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, Y.B.; Hakanson, B.; Martinek, J.; Repici, A.; von Rahden, B.H.A.; Bredenoord, A.J.; Bisschops, R.; Messmann, H.; Vollberg, M.C.; Noder, T.; et al. Endoscopic or Surgical Myotomy in Patients with Idiopathic Achalasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabi, Z.; Ramchandani, M.; Reddy, D.N. Per-oral endoscopic myotomy and gastroesophageal reflux: Where do we stand after a decade of “POETRY”? Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 38, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repici, A.; Fuccio, L.; Maselli, R.; Mazza, F.; Correale, L.; Mandolesi, D.; Bellisario, C.; Sethi, A.; Khashab, M.A.; Rosch, T.; et al. GERD after per-oral endoscopic myotomy as compared with Heller’s myotomy with fundoplication: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018, 87, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Ueno, A.; Shimamura, Y.; Manolakis, A.; Sharma, A.; Kono, S.; Nishimoto, M.; Sumi, K.; Ikeda, H.; Goda, K.; et al. Peroral endoscopic myotomy and fundoplication: A novel NOTES procedure. Endoscopy 2019, 51, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, A.; Schuchert, M.J.; Pennathur, A.; Landreneau, R.J.; Alvelo-Rivera, M.; Christie, N.A.; Gilbert, S.; Abbas, G.; Luketich, J.D. Minimally invasive myotomy for achalasia in the elderly. Surg. Endosc. 2008, 22, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Shiwaku, H.; Iwakiri, K.; Onimaru, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Minami, H.; Sato, H.; Kitano, S.; Iwakiri, R.; Omura, N.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for peroral endoscopic myotomy. Dig. Endosc. 2018, 30, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, A.; Schuchert, M.J.; Pennathur, A.; Gilbert, S.; Landreneau, R.J.; Luketich, J.D. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. Surgery 2009, 146, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; de Haro, L.F.; Parrilla, P.; Lage, A.; Perez, D.; Munitiz, V.; Ruiz, D.; Molina, J. Very long-term objective evaluation of heller myotomy plus posterior partial fundoplication in patients with achalasia of the cardia. Ann. Surg. 2008, 247, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, A.A.; Bhayani, N.; Sharata, A.; Reavis, K.; Dunst, C.M.; Swanstrom, L.L. Partial anterior vs partial posterior fundoplication following transabdominal esophagocardiomyotomy for achalasia of the esophagus: Meta-regression of objective postoperative gastroesophageal reflux and dysphagia. JAMA Surg. 2013, 148, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, R.O.; Aguilar, B.E.; Flahive, C.; Merritt, M.V.; Chapital, A.B.; Schlinkert, R.T.; Harold, K.L. Outcomes of minimally invasive myotomy for the treatment of achalasia in the elderly. JSLS 2010, 14, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, R.; Costantini, M.; Cavallin, F.; Zanatta, L.; Finotti, E.; Longo, C.; Nicoletti, L.; Capovilla, G.; Bardini, R.; Zaninotto, G. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy can be used as primary therapy for esophageal achalasia regardless of age. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014, 18, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mari, A.; Sbeit, W.; Abboud, W.; Awadie, H.; Khoury, T. Achalasia in the Elderly: Diagnostic Approach and a Proposed Treatment Algorithm Based on a Comprehensive Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5565. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10235565

Mari A, Sbeit W, Abboud W, Awadie H, Khoury T. Achalasia in the Elderly: Diagnostic Approach and a Proposed Treatment Algorithm Based on a Comprehensive Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(23):5565. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10235565

Chicago/Turabian StyleMari, Amir, Wisam Sbeit, Wisam Abboud, Halim Awadie, and Tawfik Khoury. 2021. "Achalasia in the Elderly: Diagnostic Approach and a Proposed Treatment Algorithm Based on a Comprehensive Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 23: 5565. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10235565

APA StyleMari, A., Sbeit, W., Abboud, W., Awadie, H., & Khoury, T. (2021). Achalasia in the Elderly: Diagnostic Approach and a Proposed Treatment Algorithm Based on a Comprehensive Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(23), 5565. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10235565