Iron Replacement Therapy with Oral Ferric Maltol: Review of the Evidence and Expert Opinion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Iron Replacement Therapy

3. Ferric Maltol

3.1. Preclinical and Pharmacology Studies

3.1.1. Preclinical Evidence

3.1.2. Clinical Pharmacology

3.1.3. Posology

3.2. Clinical Evidence Base

3.2.1. Study Designs

3.2.2. Efficacy Outcomes

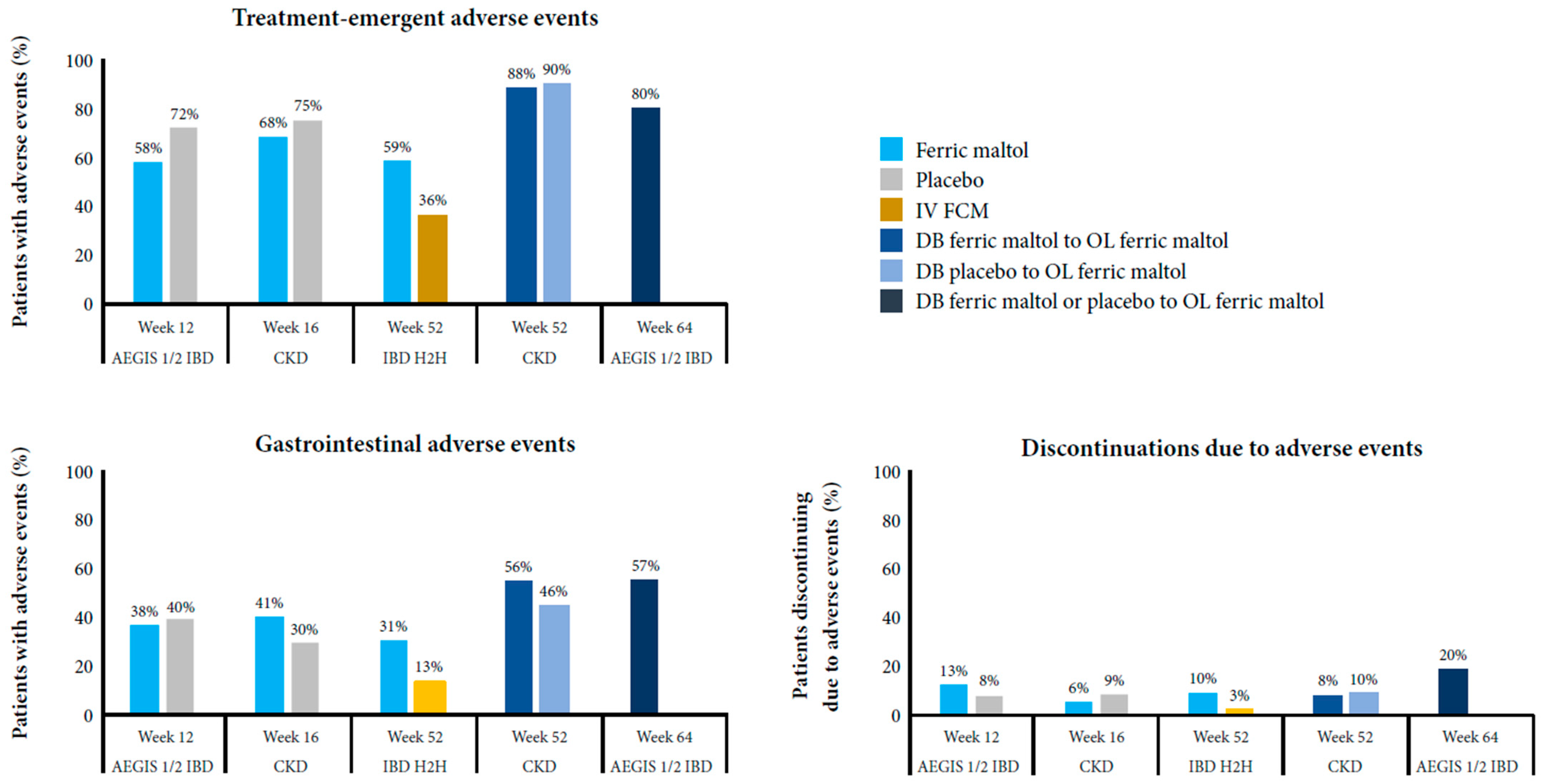

3.2.3. Safety Findings

4. Review of the Evidence and Clinical Implications

5. Summary and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System: Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. Available online: https://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Anaemia—Iron Deficiency. Available online: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/anaemia-iron-deficiency/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Gardner, W.; Kassebaum, N. Global, regional, and national prevalence of anemia and its causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, A.; Cacoub, P.; Macdougall, I.C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Iron deficiency anaemia. Lancet 2016, 387, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargallo-Puyuelo, C.J.; Alfambra, E.; García-Erce, J.A.; Gomollon, F. Iron treatment may be difficult in inflammatory diseases: Inflammatory bowel disease as a paradigm. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, N.; Hurrell, R.; Kelishadi, R. Review on iron and its importance for human health. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R. Nonhematological benefits of iron. Am. J. Nephrol. 2007, 27, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasche, C.; Lomer, M.C.; Cavill, I.; Weiss, G. Iron, anaemia, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut 2004, 53, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaitha, S.; Bashir, M.; Ali, T. Iron deficiency anemia in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2015, 6, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danese, S.; Hoffman, C.; Vel, S.; Greco, M.; Szabo, H.; Wilson, B.; Avedano, L. Anaemia from a patient perspective in inflammatory bowel disease: Results from the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Association’s online survey. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 26, 1385–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebner, N.; Jankowska, E.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Lainscak, M.; Elsner, S.; Sliziuk, V.; Steinbeck, L.; Kube, J.; Bekfani, T.; Scherbakov, N.; et al. The impact of iron deficiency and anaemia on exercise capacity and outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure—Results from the Studies Investigating Co-morbidities Aggravating Heart Failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 205, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, D.; Goldsmith, D.; Teitsson, S.; Jackson, J.; van Nooten, F. Cross-sectional survey in CKD patients across Europe describing the association between quality of life and anaemia. BMC Nephrol. 2016, 17, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, O.H.; Soendergaard, C.; Vikner, M.E.; Weiss, G. Rational management of iron-deficiency anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Alayón, C.; Pedrajas Crespo, C.; Marín Pedrosa, S.; Benítez, J.M.; Iglesias Flores, E.; Salgueiro Rodríguez, I.; Medina Medina, R.; García-Sánchez, V. Prevalence of iron deficiency without anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease and impact on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 41, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowska, E.A.; von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.D.; Macdougall, I.C.; Ponikowski, P. Iron deficiency and heart failure: Diagnostic dilemmas and therapeutic perspectives. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halterman, J.S.; Kaczorowski, J.M.; Aligne, C.A.; Auinger, P.; Szilagyi, P.G. Iron deficiency and cognitive achievement among school-aged children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics 2001, 107, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jáuregui-Lobera, I. Iron deficiency and cognitive functions. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covic, A.; Jackson, J.; Hadfield, A.; Pike, J.; Siriopol, D. Real-world impact of cardiovascular disease and anemia on quality of life and productivity in patients with non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34, 1662–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beard, J.L. Iron biology in immune function, muscle metabolism and neuronal functioning. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 568S–580S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreini, C.; Putignano, V.; Rosato, A.; Banci, L. The human iron-proteome. Metallomics 2018, 10, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, A.C.; Graham, R.M.; Trinder, D.; Olynyk, J.K. The regulation of cellular iron metabolism. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2007, 44, 413–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.; Faustino, P. An overview of molecular basis of iron metabolism regulation and the associated pathologies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignass, A.U.; Gasche, C.; Bettenworth, D.; Birgegård, G.; Danese, S.; Gisbert, J.P.; Gomollon, F.; Iqbal, T.; Katsanos, K.; Koutroubakis, I.; et al. European consensus on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2015, 9, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleyne, M.; Horne, M.K.; Miller, J.L. Individualized treatment for iron-deficiency anemia in adults. Am. J. Med. 2008, 121, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Brookes, M.J. Iron therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’amico, F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Oral iron for IBD patients: Lessons learned at time of COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girelli, D.; Ugolini, S.; Busti, F.; Marchi, G.; Castagna, A. Modern iron replacement therapy: Clinical and pathophysiological insights. Int. J. Hematol. 2018, 107, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, E.K.; Wharf, S.G.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J.; Johnson, I.T. Oral ferrous sulfate supplements increase the free radical-generating capacity of feces from healthy volunteers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolkien, Z.; Stecher, L.; Mander, A.P.; Pereira, D.I.; Powell, J.J. Ferrous sulfate supplementation causes significant gastrointestinal side-effects in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, J.; Aghdassi, E.; Platt, I.; Cullen, J.; Allard, J.P. Effect of oral iron supplementation on oxidative stress and colonic inflammation in rats with induced colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 15, 1989–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, B.; Li, H. Gut microbiota and iron: The crucial actors in health and disease. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, R.P.; Symons, P. Iron tablets cause histopathologically distinctive lesions in mucosal biopsies of the stomach and esophagus. Pathology 1996, 28, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, P.; Abdulla, K.; Wood, J.; James, P.; Foley, S.; Ragunath, K.; Atherton, J. Iron-induced mucosal pathology of the upper gastrointestinal tract: A common finding in patients on oral iron therapy. Histopathology 2008, 53, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laine, L.A.; Bentley, E.; Chandrasoma, P. Effect of oral iron therapy on the upper gastrointestinal tract. A prospective evaluation. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1988, 33, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLoughery, T.G. Safety of oral and intravenous iron. Acta Haematol. 2019, 142, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeggi, T.; Kortman, G.A.; Moretti, D.; Chassard, C.; Holding, P.; Dostal, A.; Boekhorst, J.; Timmerman, H.M.; Swinkels, D.W.; Tjalsma, H.; et al. Iron fortification adversely affects the gut microbiome, increases pathogen abundance and induces intestinal inflammation in Kenyan infants. Gut 2015, 64, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganini, D.; Zimmermann, M.B. The effects of iron fortification and supplementation on the gut microbiome and diarrhea in infants and children: A review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1688s–1693s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmanand, B.A.; Kellingray, L.; Le Gall, G.; Basit, A.W.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Narbad, A. A decrease in iron availability to human gut microbiome reduces the growth of potentially pathogenic gut bacteria: An in vitro colonic fermentation study. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 67, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines: Ferrous salt. Available online: https://list.essentialmeds.org/recommendations/143 (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Litton, E.; Xiao, J.; Ho, K.M. Safety and efficacy of intravenous iron therapy in reducing requirement for allogeneic blood transfusion: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ 2013, 347, f4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Lone, E.L.; Hodson, E.M.; Nistor, I.; Bolignano, D.; Webster, A.C.; Craig, J.C. Parenteral versus oral iron therapy for adults and children with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2, Cd007857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, L.; Longhi, S.; Locatelli, F. Safety concerns about intravenous iron therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2016, 9, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, S.; Belo, L.; Reis, F.; Santos-Silva, A. Iron therapy in chronic kidney disease: Recent changes, benefits and risks. Blood Rev. 2016, 30, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snook, J.; Bhala, N.; Beales, I.L.P.; Cannings, D.; Kightley, C.; Logan, R.P.; Pritchard, D.M.; Sidhu, R.; Surgenor, S.; Thomas, W.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia in adults. Gut 2021. (Epub ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, M.; Adamson, J.W. How we diagnose and treat iron deficiency anemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokemeyer, B. Addressing unmet needs in inflammatory bowel disease. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 1037–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontoghiorghes, G.J.; Kolnagou, A.; Demetriou, T.; Neocleous, M.; Kontoghiorghe, C.N. New era in the treatment of iron deficiency anaemia using trimaltol iron and other lipophilic iron chelator complexes: Historical perspectives of discovery and future applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrand, M.A.; Callingham, B.A.; Hider, R.C. Effects of the pyrones, maltol and ethyl maltol, on iron absorption from the rat small intestine. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1987, 39, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, J.A.; Barrand, M.A.; Callingham, B.A.; Hider, R.C. Characteristics of iron(III) uptake by isolated fragments of rat small intestine in the presence of the hydroxypyrones, maltol and ethyl maltol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1988, 37, 2051–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrand, M.A.; Hider, R.C.; Callingham, B.A. The importance of reductive mechanisms for intestinal uptake of iron from ferric maltol and ferric nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA). J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1990, 42, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Barrand, M.A. Lipid peroxidation effects of a novel iron compound, ferric maltol. A comparison with ferrous sulphate. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1990, 42, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrand, M.A.; Callingham, B.A. Evidence for regulatory control of iron uptake from ferric maltol across the small intestine of the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991, 102, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrand, M.A.; Callingham, B.A.; Dobbin, P.; Hider, R.C. Dissociation of a ferric maltol complex and its subsequent metabolism during absorption across the small intestine of the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991, 102, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, S.; Hider, R.; Bloor, J.; Blake, D.; Gutteridge, C.; Newland, A. Absorption of low and therapeutic doses of ferric maltol, a novel ferric iron compound, in iron deficient subjects using a single dose iron absorption test. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 1991, 16, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxton, D.; Thompson, R.; Hider, R. Absorption of iron from ferric hydroxypyranone complexes. Br. J. Nutr. 1994, 71, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reffitt, D.M.; Burden, T.J.; Seed, P.T.; Wood, J.; Thompson, R.P.; Powell, J.J. Assessment of iron absorption from ferric trimaltol. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2000, 37, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Nisar, S.; Kazmi, S.A. Stopped-flow kinetic study of reduction of ferric maltol complex by ascorbate. J. Adv. Chem. 2016, 12, 4338–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokemeyer, B.; Krummenerl, A.; Maaser, C.; Howaldt, S.; Mroß, M.; Mallard, N. Randomized open-label phase 1 study of the pharmacokinetics of ferric maltol in inflammatory bowel disease patients with iron deficiency. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2017, 42, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalhal, A.; Mansfield, J.; Sampson, M.; Lewis, S.; Lamb, C.; Frau, A.; Pritchard, D.; Probert, C. PTH-102 Ferric maltol, unlike ferrous sulphate, does not adversely affect the intestinal microbiome. Gut 2019, 68, A84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.; Reffitt, D.; Doig, L.; Meenan, J.; Ellis, R.; Thompson, R.; Powell, J. Ferric trimaltol corrects iron deficiency anaemia in patients intolerant of iron. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 12, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasche, C.; Ahmad, T.; Tulassay, Z.; Baumgart, D.C.; Bokemeyer, B.; Büning, C.; Howaldt, S.; Stallmach, A. Ferric maltol is effective in correcting iron deficiency anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a phase-3 clinical trial program. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Büning, C.; Ahmad, T.; Bokemeyer, B.; Elisei, W.; Picchio, M.; Penna, A.; Giorgetti, G. Correcting iron deficiency anaemia in IBD with oral ferric maltol: Use of proton pump inhibitors does not affect efficacy. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2015, 9, S339–S340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schmidt, C.; Ahmad, T.; Tulassay, Z.; Baumgart, D.; Bokemeyer, B.; Howaldt, S.; Stallmach, A.; Büning, C.; AEGIS Study Group. Ferric maltol therapy for iron deficiency anaemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Long-term extension data from a Phase 3 study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quraishi, N.; Smith, S.; Ward, D.; Sharma, N.; Sampson, M.; Tselepis, C.; Iqbal, T. PTH-113 Disease activity affects response to enteral iron supplementation: Post-hoc analysis of data from the AEGIS study. Gut 2017, 66, A262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Forsythe, A.; Sampson, M.; Tremblay, G.; Dolph, M. PSY19—Using a Bayesian network meta-analysis (NMA) to compare ferric maltol to treatments for iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia excluding CHF and CKD patients. Value Health 2018, 21, S439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopyt, N.P. Effect of oral ferric maltol on iron parameters in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and varying degrees of inflammation: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 176. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, K.M.; Fuge, J.; Brod, T.; Kamp, J.C.; Schmitto, J.; Kempf, T.; Bauersachs, J.; Hoeper, M.M. Oral iron supplementation with ferric maltol in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2000616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.F.; Fraser, A.; Stansfield, C.; Beales, I.; Sebastian, S.; Hoque, S. Ferric maltol Real-world Effectiveness Study in Hospital practice (FRESH): Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving ferric maltol for iron-deficiency anaemia in the UK. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021, 8, e000530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong, P.; Lovato, S.; Akbar, A. PTU-124 Real world tolerability & efficacy of oral ferric maltol (Feraccru) in IBD associated anaemia. Gut 2018, 67, A252–A253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, S.; Domènech, E.; Martinez, N.; Schmidt, C.; Bokemeyer, B. Long-term effectiveness of oral ferric maltol versus intravenous ferric carboxymaltose for the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A randomized controlled noninferiority trial. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021. (Epub ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, P.E.; Kopyt, N.P. Oral ferric maltol for the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease: Phase 3, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial and open-label extension. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2021. (Epub ahead of print). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Auth, M.K.-H.; Kim, J.J.; Vadamalayan, B. Safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of oral ferric maltol in children with iron deficiency: Phase 1 study. JPGN Rep. 2021, 2, e090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, G.; Dolph, M.; Jones, T.; Forsythe, A.; Mellor, L.; Sampson, M. PSY94—Cost-effectiveness model comparing therapeutic strategies for treating iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Value Health 2018, 21, S452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, G.; Forsythe, A.; Rabe, A.; Jones, T. Comparing short form–6 dimension (SF-6D) derived utilities and EuroQol questionnaire—5 dimensions (EQ-5D) mapped utilities among patients with iron deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease (ID-IBD) treated with ferric maltol (FM) vs placebo. Value Health 2018, 21, S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmgren, J.; Ericson, O.; Niska, P.; Kukkonen, P.; Birgegård, G. PSY98—Cost-effectiveness analysis of ferric maltol versus ferric carboxymaltose for the treatment of iron deficiency anaemia in IBD patients in Sweden and Finland. Value Health 2018, 21, S452–S453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovato, S.; Oppong, P.; Akbar, A. Evaluation of ferric maltol as alternative to parenteral iron therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in terms of costs reductions and healthcare human resource utilisation. Hemasphere 2018, 2, 1066. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, C.; Baumgart, D.; Bokemeyer, B.; Büning, C.; Howaldt, S.; Stallmach, A.; Singfield, C.; Tremblay, G.; Jones, T. P478 Treatment with ferric maltol associated with improvements in quality of life for IBD patients with iron deficiency anaemia. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2018, 12, S346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, S.; Jacob, I.; Sampson, M.; Akriche, F. P331 Productivity loss in patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving treatment for iron deficiency anaemia: A comparison of ferric maltol and IV iron. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2020, 14, S319–S320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, S.; Jacob, I.; Sampson, M.; Akriche, F. P567 Impact of oral ferric maltol and IV iron on health-related quality of life in patients with iron deficiency anaemia and inflammatory bowel disease, and relationship with haemoglobin and serum iron. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2020, 14, S478–S479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, S.; Jacob, I.; Sampson, M.; Akriche, F. P685 Healthcare resource use associated with ferric maltol and IV iron treatment for iron deficiency anaemia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2020, 14, S558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, S.; Becker, C.K.; Becker, J.A.; Poinas, A.C. P592 Costs savings associated with ferric maltol and the reduced use of intravenous iron based on real world data. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, S541–S542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalhal, A.; Frau, A.; Burkitt, M.D.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Lamb, C.A.; Mansfield, J.C.; Lewis, S.; Pritchard, D.M.; Probert, C.S. Oral ferric maltol does not adversely affect the intestinal microbiome of patients or mice, but ferrous sulphate does. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akriche, F.; Jacob, I.; Schmidt, C.; Howaldt, S. P420 Comparative efficacy and safety of oral ferric maltol in inflammatory bowel disease patients with mild-to-moderate vs. more severe iron deficiency anaemia. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, S424–S425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, M.N.; Arriaga, C.; Solomons, N.W.; Schümann, K. Equivalent effects on fecal reactive oxygen species generation with oral supplementation of three iron compounds: Ferrous sulfate, sodium iron EDTA and iron polymaltose. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 60, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertuccelli, G.; Marotta, F.; Zerbinati, N.; Cabeca, A.; He, F.; Jain, S.; Lorenzetti, A.; Yadav, H.; Milazzo, M.; Calabrese, F.; et al. Iron supplementation in young iron-deficient females causes gastrointestinal redox imbalance: Protective effect of a fermented nutraceutical. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2014, 28, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Feraccru: EPAR—Public Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/feraccru-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- European Medicines Agency. Feraccru (Ferric Maltol) Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/feraccru-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Food & Drug Administration. Accrufer (Ferric Maltol) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212320Orig1s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Swissmedic. Feraccru Product Information. Available online: https://www.swissmedicinfo.ch/?Feraccru (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- British Columbia Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. Iron Deficiency—Diagnosis and Management. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/bc-guidelines/iron-deficiency.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Four-Way Crossover Study to Compare Ferric Maltol Capsules and Oral Suspension in Healthy Volunteers. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04626414 (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Gordon, M.; Sinopoulou, V.; Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z.; Iqbal, T.; Allen, P.; Hoque, S.; Engineer, J.; Akobeng, A.K. Interventions for treating iron deficiency anaemia in inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 1, Cd013529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonovas, S.; Fiorino, G.; Allocca, M.; Lytras, T.; Tsantes, A.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S. Intravenous versus oral iron for the treatment of anemia in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2016, 95, e2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Location | Underlying Condition | Anemia and Iron Deficiency Definitions | Patients, N | Design | Comparator | Primary Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | |||||||

| Phase III IBD (AEGIS 1/2) [62,64] | Global | Eligibility criteria: Quiescent or mild or moderate IBD UC: SCCAI score <4 at screening and randomization CD: CDAI score <220 at randomization At baseline: UC: FM n = 29; placebo n = 29 Median (range) SCCAI score: FM 2.0 (0–3); placebo 2.0 (0–3) CD: FM n = 35; placebo n = 35 Median (range) CDAI score: FM 75 (14–199); placebo 108 (10–220) | Hb ≥9.5 to <12.0 g/dL (women) or <13.0 g/dL (men) Ferritin <30 μg/L at screening | 128 (FM n = 64; placebo n = 64) 97 started OL FM after DB FM (n = 50) or DB placebo (n = 47) | Randomized, DB, superiority52-week OL extension | Placebo (DB period only) | Hb change from baseline to week 12 |

| Phase IIIB IBD (H2H) [71] | Global | Eligibility criteria: Quiescent or mild or moderate IBD UC: SCCAI score ≤5 during screening CD: CDAI score ≤300 during screening At baseline: UC: FM n = 46, IV FCM n = 46 Mean (SD) SCCAI score: FM 2.2 (1.8); IV FCM 2.3 (1.6) CD: FM n = 79, IV FCM n = 79 Mean (SD) CDAI score: FM 129.6 (60.1); IV FCM 140.5 (75.8) | Hb ≥8.0 to ≤11.0 g/dL (women) or ≤12.0 g/dL (men) Ferritin <30 μg/L or ferritin <100 μg/L + TSAT <20% | 250 (ITT: FM n = 125, IV FCM n = 125; PP: FM n = 78, IV FCM n = 88) | Randomized, OL, non-inferiority | IV FCM | Hb responder rate at week 12 (≥2 g/dL increase or normalization) |

| Phase III CKD [72] | USA | Eligibility criteria: CKD stage III or IV (eGFR ≥15 to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, not on dialysis) At baseline:Mean (SD) eGFR: FM 31.9 (11.5) mL/min/1.73 m2 Placebo 29.7 (10.6) mL/min/1.73 m2 | Hb ≥8.0 to <11.0 g/dL Ferritin <250 μg/L + TSAT <25% or ferritin <500 μg/L + TSAT <15% | 167 (FM n = 111; placebo n = 56) 125 started OL FM after 16 weeks of DB FM (n = 86) or DB placebo (n = 39) | Randomized, DB, superiority36-week OL extension | Placebo | Hb change from baseline to week 16 |

| Phase IIIB PH [68]‘ | Germany | Eligibility criteria: any form of PH with mean resting pulmonary artery pressure ≥25 mmHg At baseline: PAH (n = 14) PH due to left heart disease (n = 1) Inoperable chronic thromboembolic PH (n = 7) Mean (SD) pulmonary artery pressure 50 (11) mmHg | Hb ≥7 to <12 g/dL (women) or ≥8 to <13 g/dL (men) Ferritin <100 μg/L or ferritin 100–300 μg/L + TSAT <20% | 22 | Single-arm OL, exploratory | None | Hb change from baseline to week 12 |

| Pediatric | |||||||

| Phase I [73] | UK | Eligibility criteria: Iron deficiency of any cause At baseline: CD (n = 8) Other gastrointestinal disorders (n = 11) Vitamin D deficiency (n = 7) CKD (n = 4) Other conditions (n = 7) | Ferritin <30 μg/L or ferritin <50 μg/L + TSAT <20% | 37 | Randomized, exploratory | Different FM doses | PK, iron uptake |

| Study | Mean Hb and Change from Baseline | Hb Responder Rate 1 | Proportion of Patients Achieving Hb Normalization 2 | Proportion of Patients Achieving ≥2 g/dL Increase in Hb | Mean Ferritin | Mean TSAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase III IBD (AEGIS 1/2) [62,64] | Baseline FM: 11.0 g/dL Placebo: 11.1 g/dL Week 12 FM: 13.2 g/dL Placebo: 11.2 g/dL Mean (SE) difference in change from baseline to week 12 FM vs. placebo: 2.25 (0.12) g/dL p < 0.0001 Up to week 64 DB FM to OL FM: 13.95 g/dL DB placebo to OL FM: 13.33 g/dL | NR | Week 12 FM: 66% Placebo: 13% Up to week 64 DB FM/placebo to OL FM: 86% | Week 12 FM: 56% Placebo: 0 Up to week 64%NR | Baseline FM: 8.6 μg/L Placebo: 8.2 μg/L Week 12 FM: 26.0 μg/L Placebo: 9.8 μg/L Mean increase at week 12 FM: 17.3 μg/L Placebo: 1.2 μg/L Up to week 64 DB FM/placebo to OL FM: 57.4 μg/L | Baseline FM: 10.6% Placebo: 9.5% Week 12 FM: 28.5% Placebo: 9.8% Mean increase at week 12 FM: 18.0 percentage points Placebo: −0.4 percentage points Up to week 64 DB FM/placebo to OL FM: 29% |

| Phase IIIB IBD (H2H) [71] | ITT population Baseline FM: 10.0 g/dL IV FCM: 10.1 g/dL Week 12 FM: 12.5 g/dL IV FCM: 13.2 g/dL LSM difference (95% CI) between groups at week 12 FM–IV FCM: −0.6 (−1.0 to −0.2) g/dL p = 0.002 Up to week 52/EoT FM: 12.8 g/dL IV FCM: 13.0 g/dL | ITT population Week 12 FM: 67% IV FCM: 84% Risk difference (95% CI) FM–IV FCM: −0.17 (−0.28 to −0.06) PP population Week 12 FM: 68% IV FCM: 85% Risk difference (95% CI) FM–IV FCM: −0.17 (−0.30 to 0.05) 3 | ITT population Week 12 FM: 55% IV FCM: 81% Up to week 52/EoT NR | ITT population Week 12 FM: 61% IV FCM: 77% Up to week 52/EoT NR | ITT population Baseline FM: 16.6 μg/L IV FCM: 9.2 μg/L Week 12 FM: 25.7 μg/L IV FCM: 139.2 μg/L LSM difference (95% CI) between groups at week 12 FM–IV FCM: −113.1 (−145.9 to –80.2) μg/L p < 0.001 Up to week 52/EoT FM: 78.9 μg/L IV FCM: 103.4 μg/L | NR |

| Phase III CKD [72] | Baseline FM: 10.1 g/dL Placebo: 10.0 g/dL LSM change from baseline to week 16 FM: 0.5 g/dL Placebo: −0.0 g/dL LSM (SE) difference between groups at week 16 FM–placebo: 0.5 (0.2) g/dL p = 0.01 Up to week 52/EoT DB FM to OL FM: 10.9 g/dL DB placebo to OL FM: 10.9 g/dL | NR | Week 16 FM: 27% Placebo: 13% Up to week 52/EoT NR | Week 16 FM: 6% Placebo: 0 Up to week 52/EoT NR | Baseline FM: 97.0 μg/L Placebo: 104.2 μg/L LSM change from baseline to week 16 FM: 25.4 μg/L Placebo: −7.2 μg/L LSM (SE) difference between groups at week 16 FM–placebo: 32.7 (9.4) μg/L p < 0.001 Up to week 52/EoT DB FM to OL FM: 142.5 μg/L DB placebo to OL FM: 146.3 μg/L | Baseline FM: 15.7% Placebo: 15.6% LSM change from baseline to week 16 FM: 3.8 percentage points Placebo: −0.9 percentage points LSM (SE) difference between groups at week 16 FM–placebo: 4.6 (1.1) percentage points p < 0.001 Up to week 52/EoT DB FM to OL FM: 23.5% DB placebo to OL FM: 21.4% |

| Phase IIIB PH [68] | Baseline FM: 10.7 g/dL Week 12 FM: 13.6 g/dL Median increase from baseline to week 12: 2.9 g/dL p < 0.001 | NR | NR | NR | Baseline FM: 13.1 μg/L Week 12 FM: 36.6 μg/L p < 0.001 | Baseline FM: 7.5% Week 12 FM: 31.7% p < 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmidt, C.; Allen, S.; Kopyt, N.; Pergola, P. Iron Replacement Therapy with Oral Ferric Maltol: Review of the Evidence and Expert Opinion. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194448

Schmidt C, Allen S, Kopyt N, Pergola P. Iron Replacement Therapy with Oral Ferric Maltol: Review of the Evidence and Expert Opinion. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021; 10(19):4448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194448

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmidt, Carsten, Stephen Allen, Nelson Kopyt, and Pablo Pergola. 2021. "Iron Replacement Therapy with Oral Ferric Maltol: Review of the Evidence and Expert Opinion" Journal of Clinical Medicine 10, no. 19: 4448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194448

APA StyleSchmidt, C., Allen, S., Kopyt, N., & Pergola, P. (2021). Iron Replacement Therapy with Oral Ferric Maltol: Review of the Evidence and Expert Opinion. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(19), 4448. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10194448