Protection Against Salmonella by Vaccination with Toxin–Antitoxin Self-Destructive Bacteria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. Construction of Modified TA Systems

2.3. Survival Following Invasion into Macrophages

2.4. Chicken Experiments

2.5. In Vivo Activity of TA Systems and Challenge Experiments

2.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for Testing Levels of SALMONELLA—Specific Antibodies

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

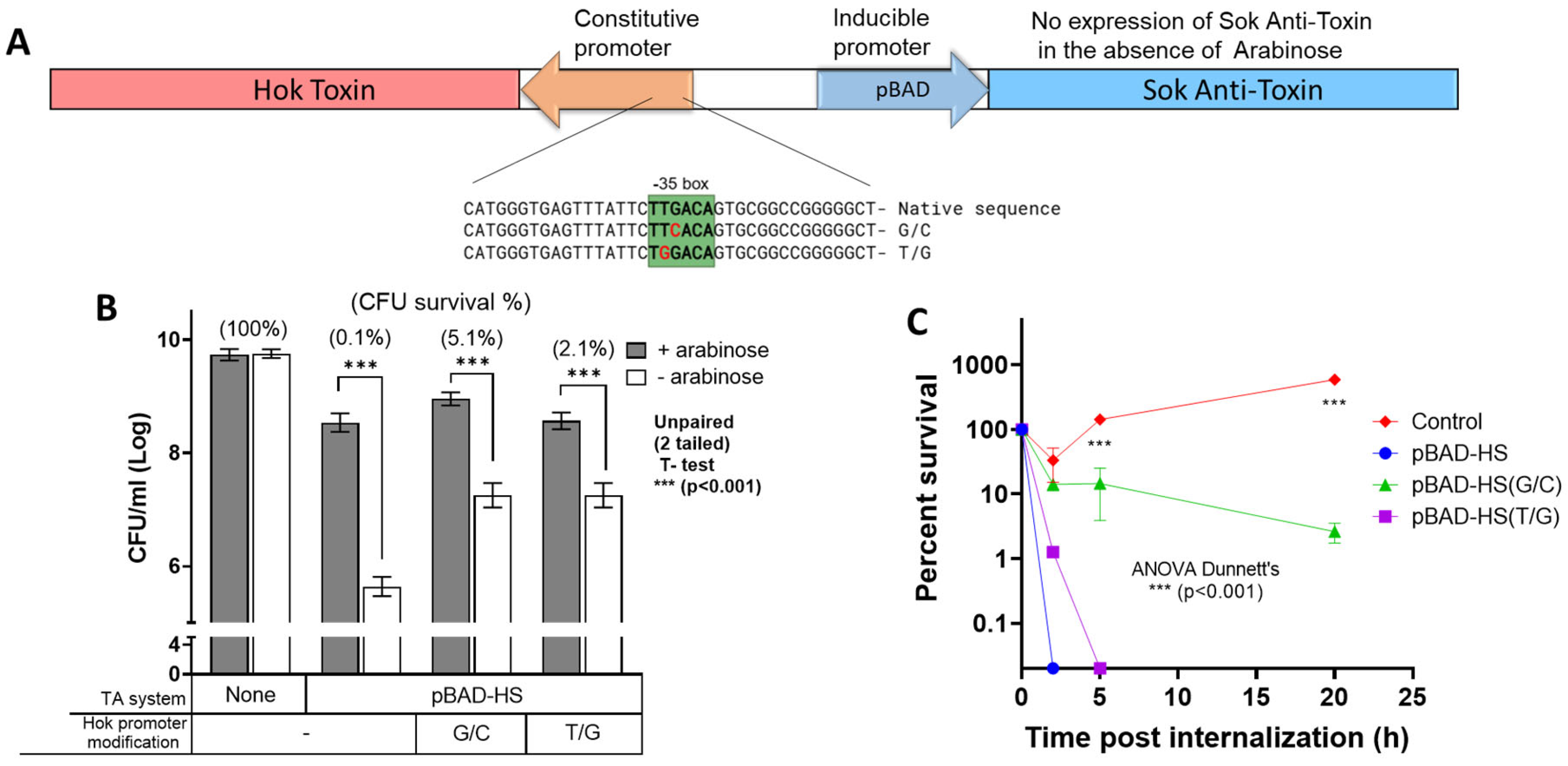

3.1. Effects of Attenuation of the Constitutive Hok Toxin Promoter on Salmonella Survival Under Restrictive Conditions and Within Macrophages

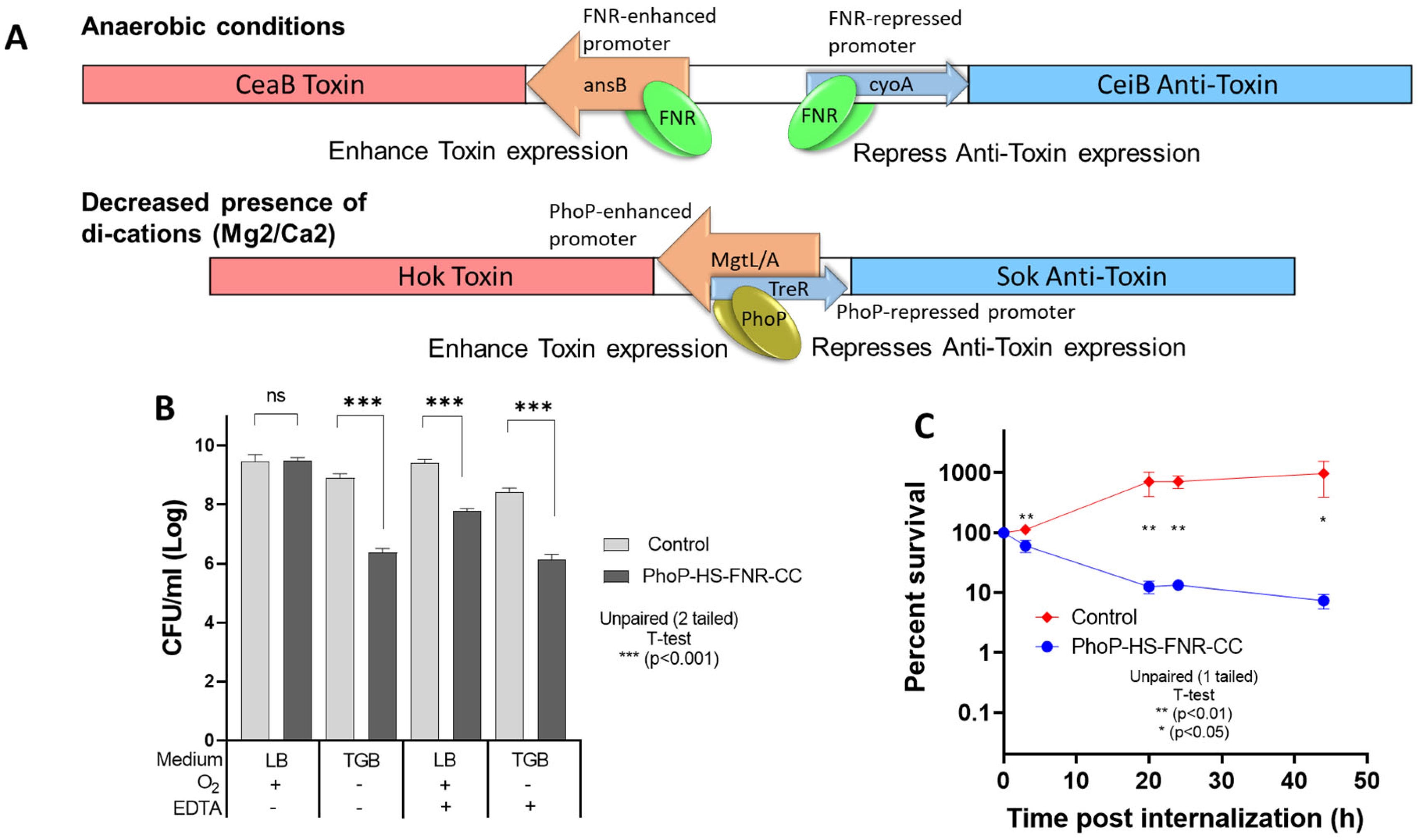

3.2. Survival of PhoP-HS-FNR-CC-Bearing Salmonella Under Restrictive Conditions and Within Macrophages

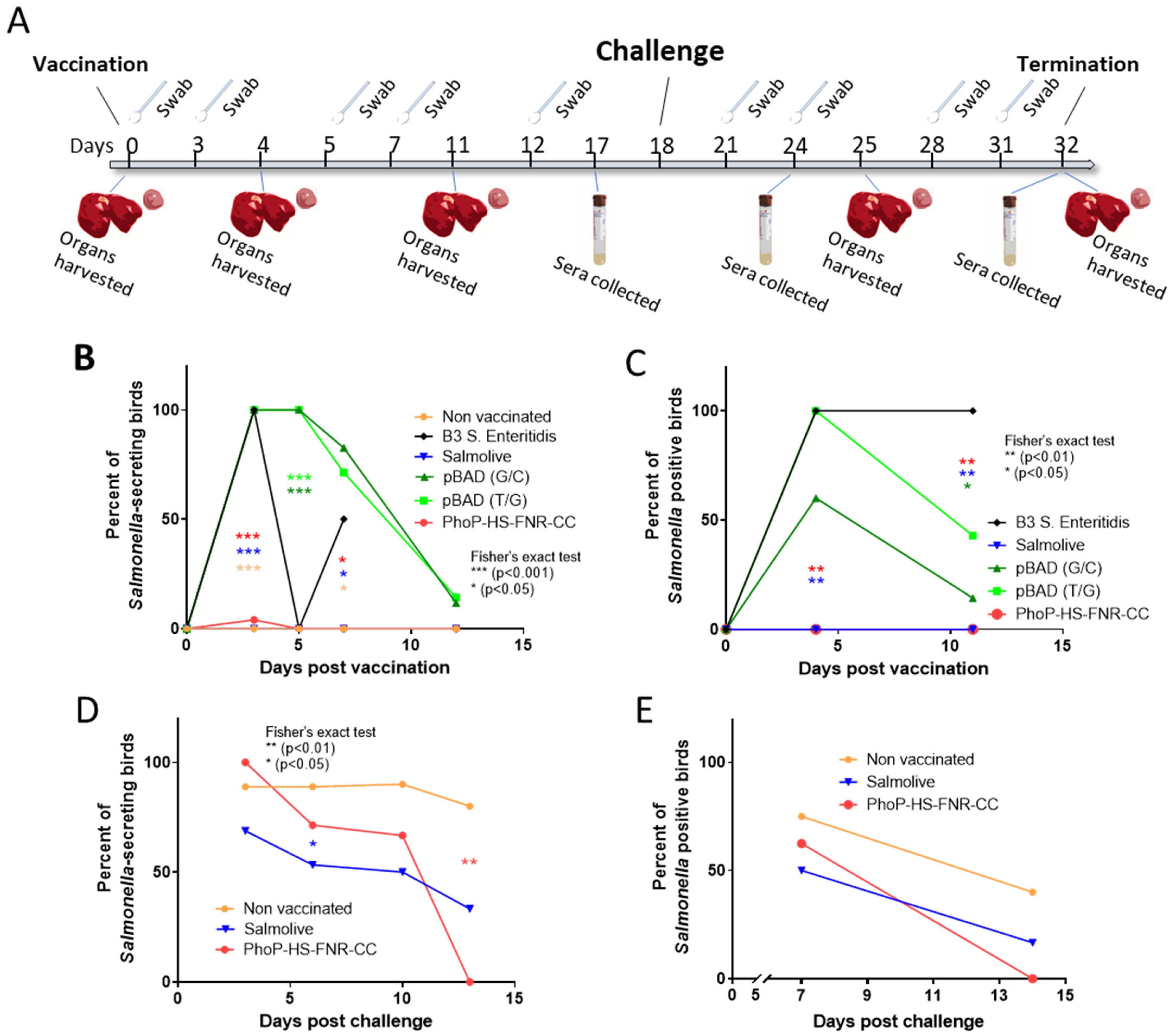

3.3. Survival and Shedding of Salmonella Carrying Modified TA Systems in Chickens

3.4. Challenge Experiments

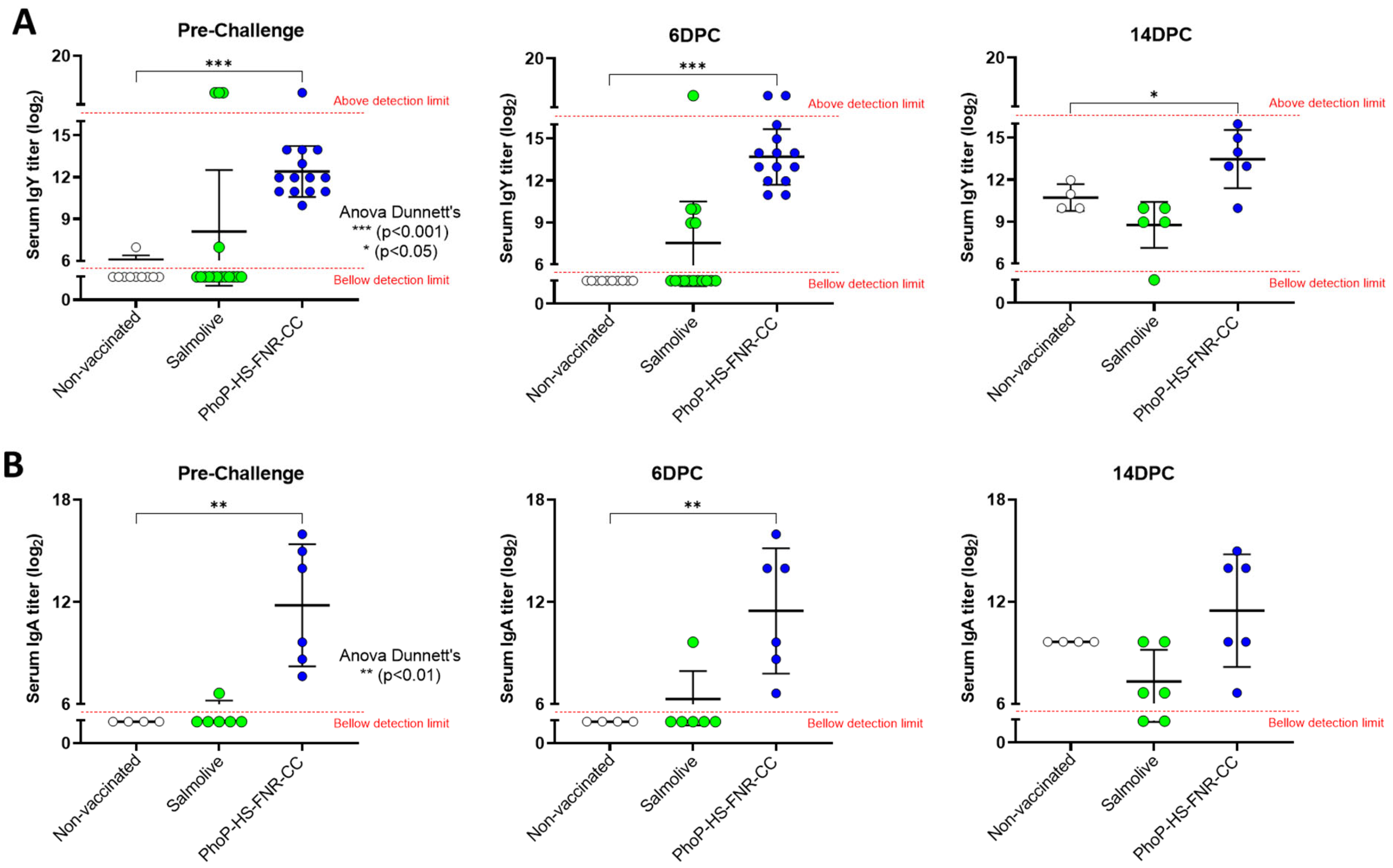

3.5. Antibody Levels Following Immunization of Chickens with PhoP-HS-FNR-CC-Bearing Salmonella

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chimalizeni, Y.; Kawaza, K.; Molyneux, E. The epidemiology and management of non typhoidal Salmonella infections. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 659, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cogan, T.A.; Humphrey, T.J. The rise and fall of Salmonella Enteritidis in the UK. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varmuzova, K.; Faldynova, M.; Elsheimer-Matulova, M.; Sebkova, A.; Polansky, O.; Havlickova, H.; Sisak, F.; Rychlik, I. Immune protection of chickens conferred by a vaccine consisting of attenuated strains of Salmonella Enteritidis, Typhimurium and Infantis. Vet. Res. 2016, 47, 94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Desin, T.S.; Koster, W.; Potter, A.A. Salmonella vaccines in poultry: Past, present and future. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2013, 12, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, P.A. Salmonella infections: Immune and non-immune protection with vaccines. Avian Pathol. 2007, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Gyles, C.L.; Wilkie, B.N. Evaluation of an aroA mutant Salmonella typhimurium vaccine in chickens using modified semisolid Rappaport Vassiliadis medium to monitor faecal shedding. Vet. Microbiol. 1997, 54, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T.J.; Flores-Figueroa, C.; Munoz-Aguayo, J.; Pinho, G.; Miller, E. Persistence of vaccine origin Salmonella Typhimurium through the poultry production continuum, and development of a rapid typing scheme for their differentiation from wild type field isolates. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzdev, N.; Pitcovski, J.; Katz, C.; Ruimi, N.; Eliahu, D.; Noach, C.; Rosenzweig, E.; Finger, A.; Shahar, E. Development of toxin-antitoxin self-destructive bacteria, aimed for Salmonella vaccination. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4918–4925. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, S.F.H.; Leinberger, F.H.; Fozo, E.M.; Berghoff, B.A. Type I toxin-antitoxin systems in bacteria: From regulation to biological functions. EcoSal Plus 2024, 12, eesp00252022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurenas, D.; Fraikin, N.; Goormaghtigh, F.; Van Melderen, L. Biology and evolution of bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Park, J.H.; Inouye, M. Toxin-antitoxin systems in bacteria and archaea. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011, 45, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, K.; Thisted, T.; Martinussen, J. Mechanism of post-segregational killing by the hok/sok system of plasmid R1: Sok antisense RNA regulates formation of a hok mRNA species correlated with killing of plasmid-free cells. Mol. Microbiol. 1990, 4, 1807–1818. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwudi, C.U.; Good, L. Good, The role of the hok/sok locus in bacterial response to stressful growth conditions. Microb. Pathog. 2015, 79, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugsley, A.P.; Goldzahl, N.; Barker, R.M. Colicin E2 production and release by Escherichia coli K12 and other Enterobacteriaceae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1985, 131, 2673–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, S.-K.; Pusparajah, P.; Ab Mutalib, N.-S.; Ser, H.-L.; Chan, K.-G.; Lee, L.-H. Salmonella: A review on pathogenesis, epidemiology and antibiotic resistance. Front. Life Sci. 2015, 8, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiley, P.J.; Beinert, H. Oxygen sensing by the global regulator, FNR: The role of the iron-sulfur cluster. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 22, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, R.C.; Evans, M.R.; Porwollik, S.; Vazquez-Torres, A.; Jones-Carson, J.; Troxell, B.; Libby, S.J.; McClelland, M.; Hassan, H.M. FNR is a global regulator of virulence and anaerobic metabolism in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (ATCC 14028s). J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 2262–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantinidou, C.; Hobman, J.L.; Griffiths, L.; Patel, M.D.; Penn, C.W.; Cole, J.A.; Overton, T.W. A reassessment of the FNR regulon and transcriptomic analysis of the effects of nitrate, nitrite, NarXL, and NarQP as Escherichia coli K12 adapts from aerobic to anaerobic growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 4802–4815. [Google Scholar]

- Monsieurs, P.; De Keersmaecker, S.; Navarre, W.W.; Bader, M.W.; De Smet, F.; McClelland, M.; Fang, F.C.; De Moor, B.; Vanderleyden, J.; Marchal, K. Comparison of the PhoPQ regulon in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J. Mol. Evol. 2005, 60, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mey, M.; Maertens, J.; Lequeux, G.J.; Soetaert, W.K.; Vandamme, E.J. Construction and model-based analysis of a promoter library for E. coli: An indispensable tool for metabolic engineering. BMC Biotechnol. 2007, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wei, R.-R.; Xu, P.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Li, C.; Ding, G.-W.; Fan, J.; Li, Y.-H.; Yu, J.-Y.; Dai, P. Progress in the application of Salmonella vaccines in poultry: A mini review. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2024, 278, 110855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beylefeld, A.; Abolnik, C. Salmonella gallinarum strains from outbreaks of fowl typhoid fever in Southern Africa closely related to SG9R vaccines. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1191497. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.H.; Ko, D.-S.; Ha, E.-J.; Ahn, S.; Choi, K.-S.; Kwon, H.-J. Optimized Detoxification of a Live Attenuated Vaccine Strain (SG9R) to Improve Vaccine Strategy against Fowl Typhoid. Vaccines 2021, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo-Villanueva, K.Y.; Akerele, G.O.; Al Hakeem, W.G.; Renu, S.; Shanmugasundaram, R.; Selvaraj, R.K. A Novel Approach against Salmonella: A Review of Polymeric Nanoparticle Vaccines for Broilers and Layers. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svahn, A.J.; Chang, S.L.; Rockett, R.J.; Cliff, O.M.; Wang, Q.; Arnott, A.; Ramsperger, M.; Sorrell, T.C.; Sintchenko, V.; Prokopenko, M. Genome-wide networks reveal emergence of epidemic strains of Salmonella Enteritidis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 117, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plocica, J.; Guo, F.; Das, J.K.; Kobayashi, K.S.; Ficht, T.A.; Alaniz, R.C.; Song, J.; de Figueiredo, P. Engineering live attenuated vaccines: Old dogs learning new tricks. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2023, 6, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, S.; Selvaraj, R.K.; Shanmugasundaram, R. Salmonella Infection in Poultry: A Review on the Pathogen and Control Strategies. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameiss, K.; Ashraf, S.; Kong, W.; Pekosz, A.; Wu, W.-H.; Milich, D.; Billaud, J.-N.; Curtiss, R. Delivery of woodchuck hepatitis virus-like particle presented influenza M2e by recombinant attenuated Salmonella displaying a delayed lysis phenotype. Vaccine 2010, 28, 6704–6713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Kong, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Curtiss, R. Protective cellular responses elicited by vaccination with influenza nucleoprotein delivered by a live recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine. Vaccine 2011, 29, 3990–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Mo, H.; Willingham, C.; Wang, S.; Park, J.-Y.; Kong, W.; Roland, K.L.; Curtiss, R. Protection Against Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Chickens by Regulated Delayed Lysis Salmonella Vaccines. Avian Dis. 2015, 59, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez-Rodriguez, M.D.; Yang, J.; Kader, R.; Alamuri, P.; Curtiss, R., III; Clark-Curtiss, J.E. Live attenuated Salmonella vaccines displaying regulated delayed lysis and delayed antigen synthesis to confer protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Brovold, M.; Koeneman, B.A.; Clark-Curtiss, J.; Curtiss, R., III. Turning self-destructing Salmonella into a universal DNA vaccine delivery platform. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 19414–19419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Wanda, S.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Bollen, W.; Tinge, S.A.; Roland, K.L.; Curtiss, R., III. Regulated programmed lysis of recombinant Salmonella in host tissues to release protective antigens and confer biological containment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9361–9366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TA System | Permissive GC | Restrictive GC |

|---|---|---|

| pBAD-HS pBAD-HS (G/C) pBAD-HS (T/G) | LB + arabinose (0.2%) | LB |

| PhoP-HS-FNR-CC | LB | 1. TGB # |

| 2. LB + EDTA (2 mM) | ||

| 3. TGB # + EDTA (2 mM) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gruzdev, N.; Pitcovski, J.; Katz, C.; Ruimi, N.; Eliahu, D.; Noach, C.; Rosenzweig, E.; Finger, A.; Shahar, E. Protection Against Salmonella by Vaccination with Toxin–Antitoxin Self-Destructive Bacteria. Vaccines 2026, 14, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010089

Gruzdev N, Pitcovski J, Katz C, Ruimi N, Eliahu D, Noach C, Rosenzweig E, Finger A, Shahar E. Protection Against Salmonella by Vaccination with Toxin–Antitoxin Self-Destructive Bacteria. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleGruzdev, Nady, Jacob Pitcovski, Chen Katz, Nili Ruimi, Dalia Eliahu, Caroline Noach, Ella Rosenzweig, Avner Finger, and Ehud Shahar. 2026. "Protection Against Salmonella by Vaccination with Toxin–Antitoxin Self-Destructive Bacteria" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010089

APA StyleGruzdev, N., Pitcovski, J., Katz, C., Ruimi, N., Eliahu, D., Noach, C., Rosenzweig, E., Finger, A., & Shahar, E. (2026). Protection Against Salmonella by Vaccination with Toxin–Antitoxin Self-Destructive Bacteria. Vaccines, 14(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010089