Vaccine-Induced Cellular Immunity against Bordetella pertussis: Harnessing Lessons from Animal and Human Studies to Improve Design and Testing of Novel Pertussis Vaccines

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Story so Far

1.2. Differences in Vaccine Composition and Host Immune Responses Go Hand-in-Hand

1.3. Evidence for the Importance of Cellular-Mediated Immunity

2. What Have We Learned about Vaccine-Induced T-Cell-Mediated Immunity from Animal Models?

2.1. The Mouse Model

2.1.1. Systemic Responses

2.1.2. Mucosal Responses

2.2. The Baboon Model

2.2.1. Colonisation and Transmission Studies

- (a)

- Following direct challenge with Bp aerosol, wP- and aP-vaccinated baboons displayed similar initial nasopharyngeal colonisation, although the former group cleared infection significantly faster than naïve and aP-immunised animals. Neither wP-vaccinated, aP-vaccinated, nor convalescent baboons showed signs of severe respiratory or systemic disease.

- (b)

- To evaluate whether vaccination prevents pertussis infection by natural transmission, two aP-vaccinated animals and one unvaccinated baboon were housed together with a directly challenged, unvaccinated baboon (who subsequently became infected). All animals were colonised by 7–10 days, with no significant differences in peak levels and kinetics of colonisation between naïve and aP-immunised baboons.

- (c)

- To confirm that aP-vaccinated baboons are not only capable of being colonised but can subsequently also transmit Bp to naïve contacts, aP-vaccinated animals were challenged with Bp and placed in separate cages. After 24 h, a naïve animal was added to each cage; both were infected by transmission from their aP-vaccinated cage mates.

2.2.2. Systemic Responses

2.2.3. Mucosal Responses

2.3. Other Animal Models

3. What Have We Learned about Vaccine-Induced T-Cell-Mediated Immunity from Human Studies?

3.1. Distinct Patterns of Cellular Immune Responses Are Induced by aP vs. wP and Are Largely Consistent with the Th1/Th2 Polarisation Observed in Animal Models

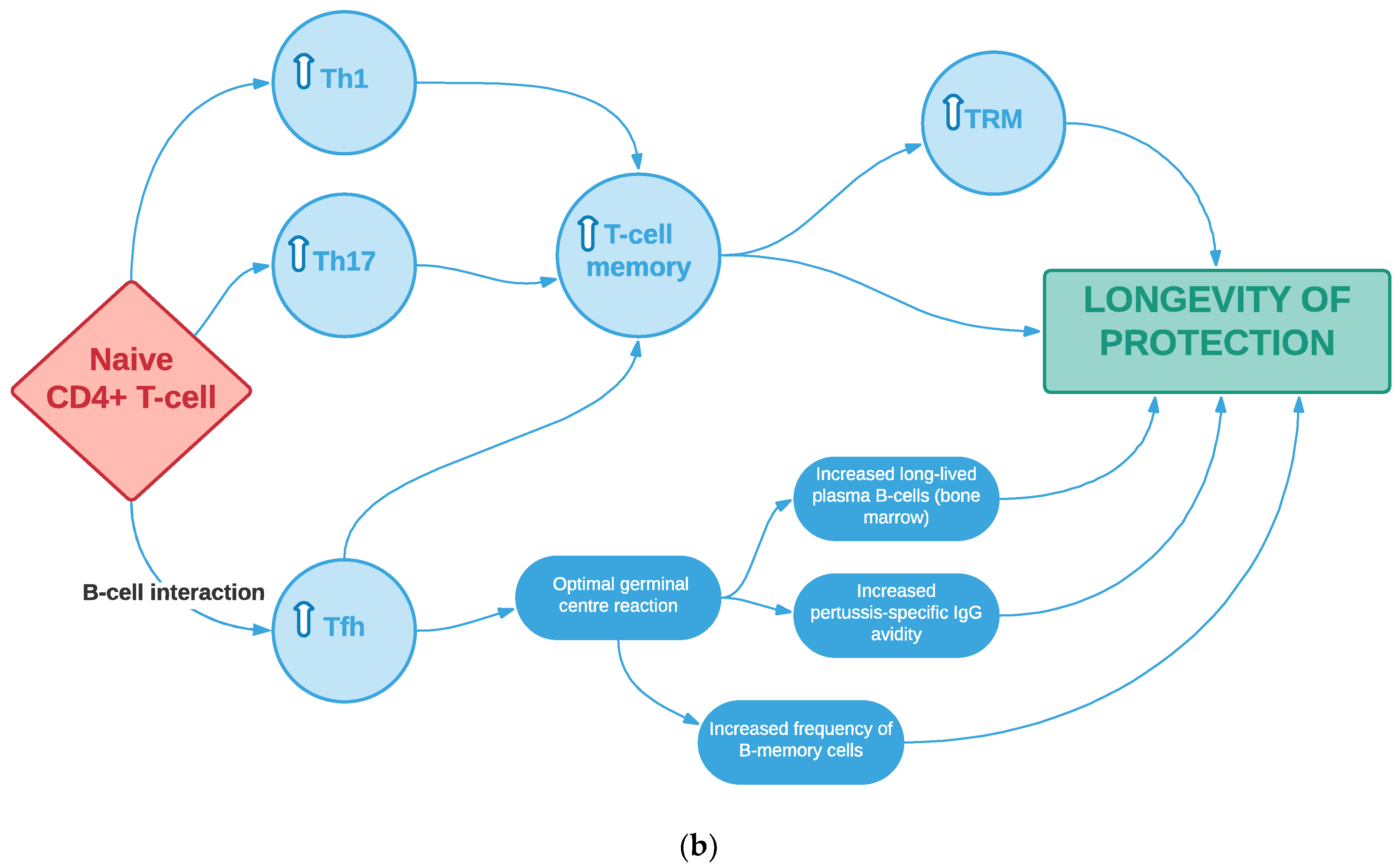

3.2. Th-Cell Polarisation Established in Infancy Persists Even if Subsequent aP Boosters Are Given in Adolescence and Adulthood

3.3. Aside from Th Skewing, Infant Vaccine Type May Influence the Strength and/or Duration of the Cellular Response

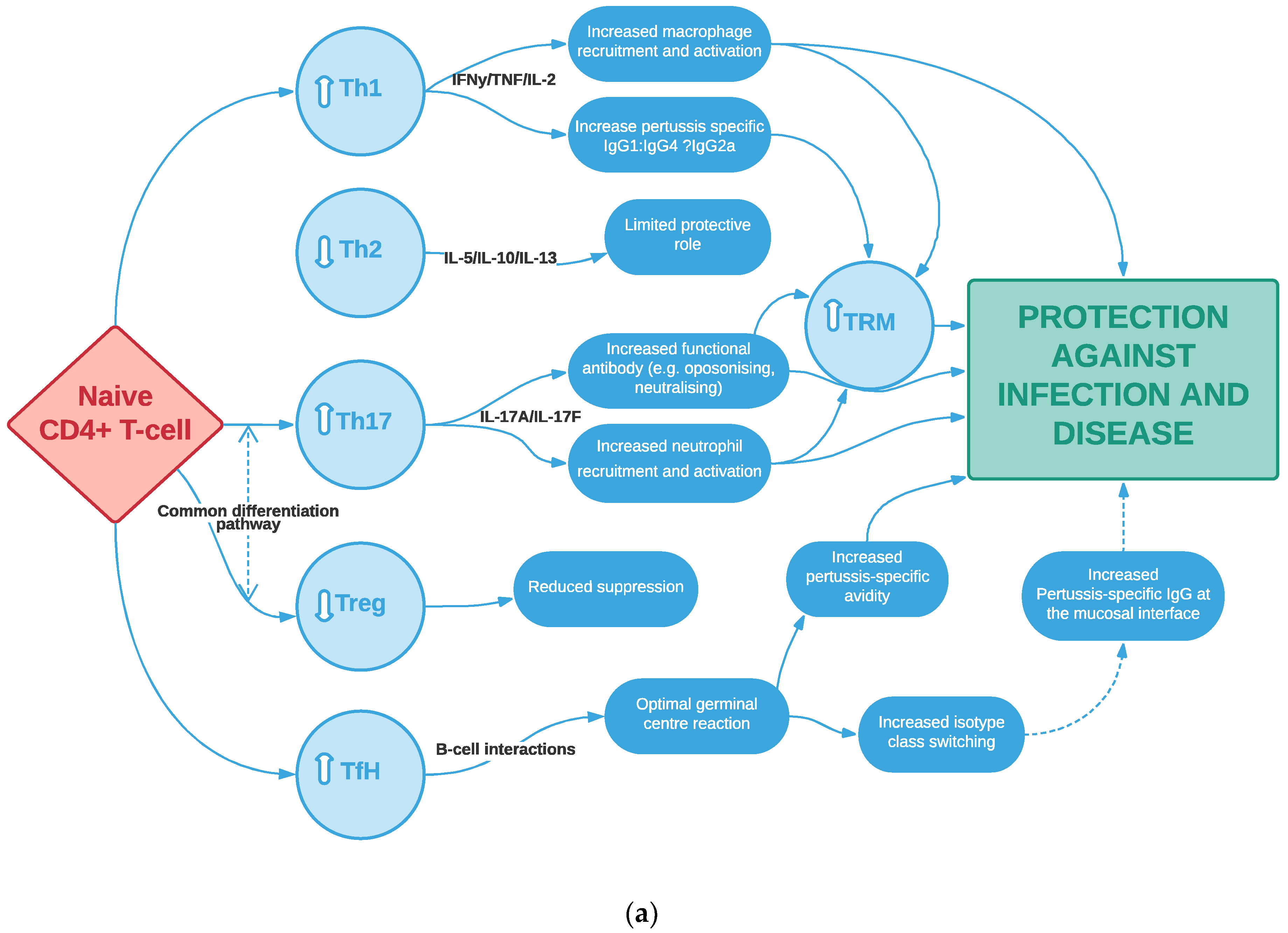

3.4. Th17 Cells, Particularly of Tissue-Resident Memory Phenotype, Potentially Play an Important Role in Pertussis Vaccine-Induced Immunity, Consistent with Animal Studies

3.5. Other T-Cell Subtypes May Play a Key Role in Vaccine-Induced Immunity

3.6. The Human Challenge Model May Help to Address Gaps in Knowledge, Particularly on Mucosal Immunity

4. Measuring Vaccine-Induced Cellular Responses in Humans

4.1. How Do We Measure T-Cell Responses in the Blood?

4.1.1. Traditional Methods

4.1.2. Flow-Cytometry Methods

- (a)

- Novel proliferation assays: Classical proliferation assays have largely been replaced by flow-cytometric readouts. Examples include fluorescent dye dilution assays, using CFSE or derivative dyes, and assays that detect BrdU by fluorochrome-conjugated antibody staining [142,147]. Proliferation dyes diffuse easily into cells and bind covalently to the amino groups of intracellular proteins; since the dyes are divided equally between daughter cells the number of cell divisions of the proliferating cells can be visualised, thus allowing the theoretical enumeration of antigen-specific cells [136,141]. Expression of Ki67, a nuclear protein that coordinates regulation of cell division, is also increasingly being used to measure specific T-cell responses induced by pertussis vaccination, including longitudinal monitoring [148].

- (b)

- Intracellular staining (ICS) is a versatile method used to analyse cytokine production at a single-cell level by flow cytometry, although it is less sensitive than ELISpot [149]. Blood or PBMCs are stimulated with the antigen(s) of interest and a transport inhibitor (e.g., BFA or monensin) is added for several hours to block secretion of the produced cytokines, thus allowing detection. Stimulated cells are then stained with fluorescently-labelled antibodies targeting surface markers then fixed, permeabilised and stained with anti-cytokine antibodies, before flow-cytometric analysis. This allows detailed phenotypic and functional analysis of pertussis-specific T-cell subsets and diverse differentiation pathways. Polyfunctionality, i.e., the ability of a cell to produce >1 cytokine, is also measured [150,151]. Technological advancements have enabled increasingly higher numbers of parameters to be assessed, although they must be pre-determined which can skew the response detected; given that standard panels in clinical trials often use IFN-γ, IL-2 and TNFα (and IL-4 can be difficult to detect), a more Th1-biased response may be established, which is particularly concerning when characterising vaccine-induced Th-immunity in pertussis vaccine research, in which establishing the ratio of different antigen-specific Th-profiles is important [138,152]. Furthermore, some memory cells may not secrete detectable levels of cytokines, especially the central compared to effector memory CD4+ population which develops at later time points after infection or vaccination [152]. Other drawbacks of this method include signal-to-noise ratio and nonspecific binding [139].

- (c)

- Peptide-MHC-II tetramer staining: MHC tetramers are based on the structural features of the T-cell receptor and consist of 4 MHC molecules which are associated with a specific peptide/epitope [153]; the complex is bound to a fluorochrome, thereby enabling the direct visualisation, quantification and phenotypic characterisation of antigen-specific T-cells using flow-cytometry, following both pertussis infection and vaccination [139,153] This method, however, requires prior knowledge of the MHC alleles of the donor (particularly challenging in a LMIC) and relevant antigenic epitopes; moreover, it only gives limited and preselected insight into the heterogeneous T-cell populations specific for a certain antigen.

- (d)

- Activation-induced marker (AIM) assays: More recently, techniques have been developed that do not require prior knowledge of MHC alleles nor focus on single cytokine responses but instead assess T-cell specificity irrespective of their functionality. Antigen-specificity is defined based on the upregulation of T-cell-receptor-stimulated surface markers, termed activation-induced markers (AIM), upon overnight antigen recall of either whole blood [154] or PBMCs [152,155], without the need for fixation and permeabilisation of cells for ICS.

4.1.3. Methods to Enrich Antigen-Specific T-Cells

4.1.4. Higher Throughput Technologies: Multidimensional Flow or Mass Cytometry

4.1.5. Omics’ Technologies

4.2. How Do We Integrate This with Knowledge of T-Cell Epitopes?

4.2.1. Epitope Mapping

4.2.2. Combine with T-Cell Receptor Sequencing

4.3. How Do We Measure T-Cell Responses in the Mucosa?

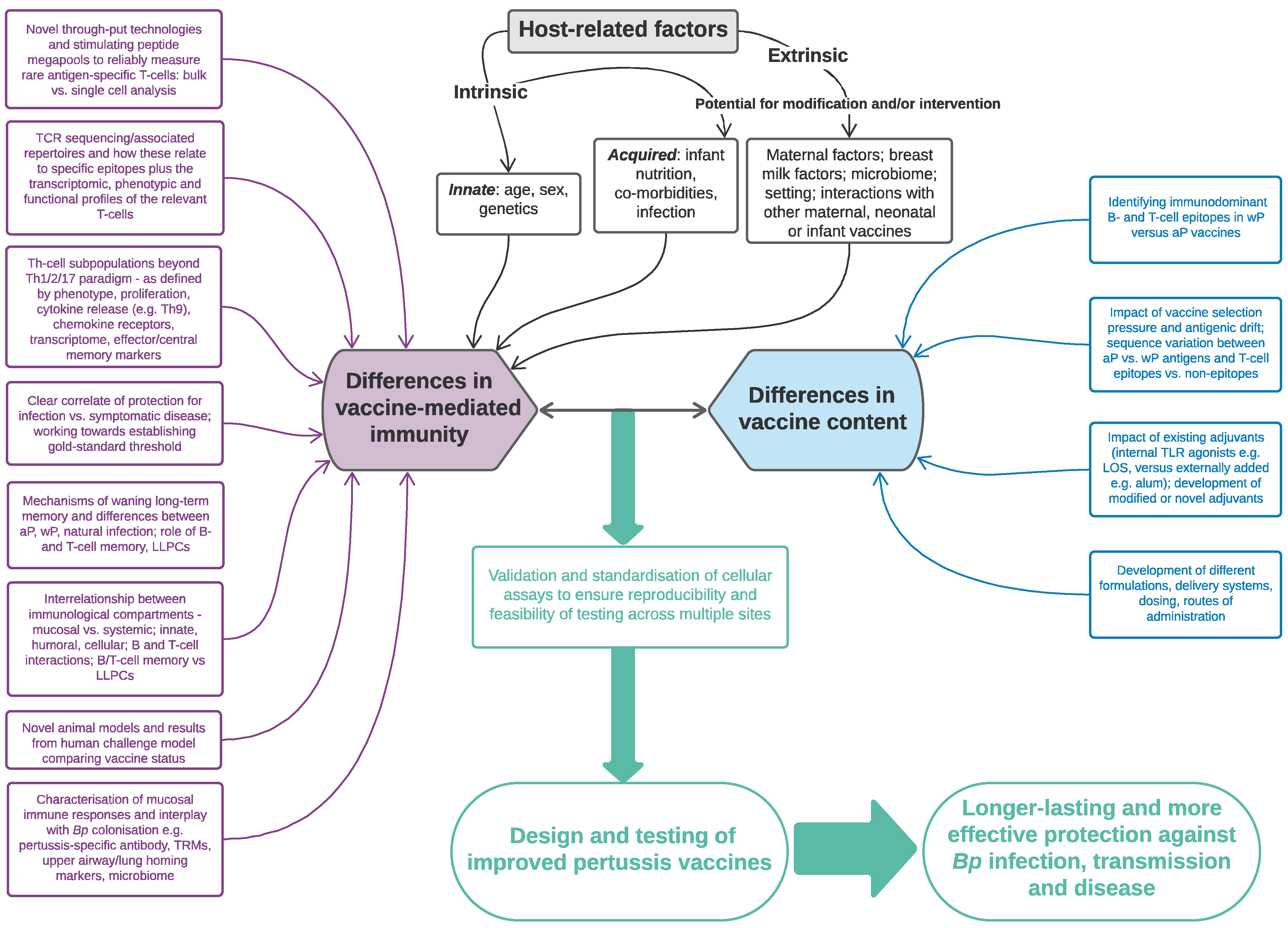

5. Which Factors May Affect T-Cell-Mediated Immunity to Pertussis Infant Vaccinations?

5.1. Vaccine-Related Factors

5.2. Host-Related Factors: Intrinsic (Innate)

5.2.1. Age

5.2.2. Sex

5.2.3. Genetics

5.3. Host-Related Factors: Intrinsic (Acquired)

5.3.1. Microbiome

5.3.2. Co-Morbidities and Malnutrition

5.4. Host-Related Factors: Extrinsic

5.4.1. Interactions with Other Neonatal/Infant Vaccines

5.4.2. Maternal Factors

6. The Future: How Can We Harness Our Knowledge of Cell-Mediated Responses to Improve the Next-Generation of Pertussis Vaccines?

6.1. Harnessing CMI to Improve Vaccine Testing

6.2. Harnessing CMI to Improve Vaccine Design and Delivery

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dewan, K.K.; Linz, B.; Derocco, S.E.; Harvill, E.T. Acellular pertussis vaccine components: Today and tomorrow. Vaccines 2020, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, J.A.; Scheller, E.V.; Miller, J.F.; Cotter, P.A. Bordetella pertussis pathogenesis: Current and future challenges. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, M.Y.K.; Khandaker, G.; McIntyre, P. Global childhood deaths from pertussis: A historical review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, S134–S141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, N.; Meade, B.D.; Wirsing von König, C.H. Pertussis vaccines: The first hundred years. Vaccine 2020, 38, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, S.; Loscher, C.E.; Lynch, M.A.; Mills, K.H.G. Whole-cell but not acellular pertussis vaccines induce convulsive activity in mice: Evidence of a role for toxin-induced interleukin-1β in a new murine model for analysis of neuronal side effects of vaccination. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 4217–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Edwards, K.M.; Berbers, G.A.M. Immune responses to pertussis vaccines and disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, S10–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, C. The Path to New Pediatric Vaccines against Pertussis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L.C. Pertussis vaccine trials in the 1990s. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, N.; Abrahams, J.S.; Bagby, S.; Preston, A.; MacArthur, I. How Genomics Is Changing What We Know About the Evolution and Genome of Bordetella pertussis. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 1183, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt, C.S.; Siegrist, C.A. What is wrong with pertussis vaccine immunity? Inducing and recalling vaccine-specific immunity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a029629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, K.H.T.; Duclos, P.; Nelson, E.A.S.; Hutubessy, R.C.W. An update of the global burden of pertussis in children younger than 5 years: A modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muloiwa, R.; Wolter, N.; Mupere, E.; Tan, T.; Chitkara, A.J.; Forsyth, K.D.; von König, C.H.W.; Hussey, G. Pertussis in Africa: Findings and recommendations of the Global Pertussis Initiative (GPI). Vaccine 2018, 36, 2385–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampmann, B.; MacKenzie, G. Morbidity and mortality due to Bordetella pertussis: A significant pathogen in west Africa? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, S142–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosa, F.; Du Plessis, M.; Wolter, N.; Carrim, M.; Cohen, C.; Von Mollendorf, C.; Walaza, S.; Tempia, S.; Dawood, H.; Variava, E.; et al. Challenges and clinical relevance of molecular detection of Bordetella pertussis in South Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, S.; Principi, N. Prevention of pertussis: An unresolved problem. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 2452–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Stefanelli, P.; Fry, N.K.; Fedele, G.; He, Q.; Paterson, P.; Tan, T.; Knuf, M.; Rodrigo, C.; Olivier, C.W.; et al. Pertussis prevention: Reasons for resurgence, and differences in the current acellular pertussis vaccines. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfel, J.M.; Edwards, K.M. Pertussis vaccines and the challenge of inducing durable immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2015, 35, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, N.P.; Bartlett, J.; Fireman, B.; Aukes, L.; Buck, P.O.; Krishnarajah, G.; Baxter, R. Waning protection following 5 doses of a 3-component diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis vaccine. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3395–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, Q. Immune persistence after pertussis vaccination. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2017, 13, 744–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althouse, B.M.; Scarpino, S.V. Asymptomatic transmission and the resurgence of Bordetella pertussis. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, S.A. The Pertussis Problem. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 830–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, M.A.; Arias, L.; Katz, P.H.; Truong, E.T.; Witt, D.J. Reduced Risk of Pertussis Among Persons Ever Vaccinated With Whole Cell Pertussis Vaccine Compared to Recipients of Acellular Pertussis Vaccines in a Large US Cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liko, J.; Robison, S.G.; Cieslak, P.R. Priming with Whole-Cell versus Acellular Pertussis Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 581–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, S.L.; Ware, R.S.; Grimwood, K.; Lambert, S.B. Unexpectedly Limited Durability of Immunity Following Acellular Pertussis Vaccination in Preadolescents in a North American Outbreak. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, 1434–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Klein, N.P.; Bartlett, J.; Fireman, B.; Baxter, R. Waning Tdap effectiveness in adolescents. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasaide, C.N.; Mills, K.H.G. Next-generation pertussis vaccines based on the induction of protective t cells in the respiratory tract. Vaccines 2020, 8, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Mattia, G.; Nicolai, A.; Frassanito, A.; Petrarca, L.; Nenna, R.; Midulla, F. Pertussis: New preventive strategies for an old disease. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2019, 29, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, F.M.; Jamieson, D.J. Maternal Immunization. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.H.G.; Barnard, A.; Watkins, J.; Redhead, K. Cell-mediated immunity to Bordetella pertussis: Role of Th1 cells in bacterial clearance in a murine respiratory infection model. Infect. Immun. 1993, 61, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfel, J.M.; Merkel, T.J. Bordetella pertussis infection induces a mucosal IL-17 response and long-lived Th17 and Th1 immune memory cells in nonhuman primates. Mucosal Immunol. 2013, 6, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfel, J.M.; Zimmerman, L.I.; Merkel, T.J. Acellular pertussis vaccines protect against disease but fail to prevent infection and transmission in a nonhuman primate model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, A.; Mahon, B.P.; Watkins, J.; Redhead, K.; Mills, K.H.G. Th1/Th2 cell dichotomy in acquired immunity to Bordetella pertussis: Variables in the in vivo priming and in vitro cytokine detection techniques affect the classification of T-cell subsets as Th1, Th2 or Th0. Immunology 1996, 87, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausiello, C.M.; Urbani, F.; La Sala, A.; Lande, R.; Cassone, A. Vaccine- and antigen-dependent type 1 and type 2 cytokine induction after primary vaccination of infants with whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccines. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 2168–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.; Yerkovich, S.T.; Richmond, P.; Suriyaarachchi, D.; Fisher, E.; Feddema, L.; Loh, R.; Sly, P.D.; Holt, P.G. Th2-associated local reactions to the acellular diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine in 4- to 6-year-old children. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 8130–8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.; Macaubas, C.; Monger, T.M.; Holt, B.J.; Harvey, J.; Poolman, J.T.; Sly, P.D.; Holt, P.G. Antigen-specific responses to diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis vaccine in human infants are initially Th2 polarized. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 3873–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.; Murphy, G.; Ryan, E.; Nilsson, L.; Shackley, F.; Gothefors, L.; Øymar, K.; Miller, E.; Storsaeter, J.; Mills, K.H.G. Distinct T-cell subtypes induced with whole cell and acellular pertussis vaccines in children. Immunology 1998, 93, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, T.; Dillon, M.B.C.; da Silva Antunes, R.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Crotty, S.; Lindestam Arlehamn, C.S.; Sette, A. Th1 versus Th2 T cell polarization by whole-cell and acellular childhood pertussis vaccines persists upon re-immunization in adolescence and adulthood. Cell. Immunol. 2016, 304–305, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Lee, S.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.-M. Whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccination in infancy determines IgG subclass profiles to DTaP booster vaccination. Vaccine 2018, 36, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Lee, S.; van Rooijen, D.M.; de Zeeuw-Brouwer, M.-L.; Bogaard, M.J.M.; van Gageldonk, P.G.M.; Marinovic, A.B.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.-M. Robust Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses to Pertussis in Adults After a First Acellular Booster Vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Twillert, I.; Han, W.G.H.; Van Els, A.C.M. Waning and aging of cellular immunity to Bordetella pertussis. FEMS Pathog. Dis. 2015, 73, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fedele, G.; Cassone, A.; Ausiello, C.M. T-cell immune responses to Bordetella pertussis infection and vaccination: Graphical Abstract Figure. Pathog. Dis. 2015, 73, ftv051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.C.; Wilk, M.M.; Misiak, A.; Borkner, L.; Murphy, D.; Mills, K.H.G. Sustained protective immunity against Bordetella pertussis nasal colonization by intranasal immunization with a vaccine-adjuvant combination that induces IL-17-secreting TRM cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 1763–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, M.M.; Mills, K.H.G. CD4 TRM Cells Following Infection and Immunization: Implications for More Effective Vaccine Design. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solans, L.; Locht, C. The Role of Mucosal Immunity in Pertussis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, S.C.; Jarnicki, A.G.; Lavelle, E.C.; Mills, K.H.G. TLR4 Mediates Vaccine-Induced Protective Cellular Immunity to Bordetella pertussis: Role of IL-17-Producing T Cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 7980–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Da Silva Antunes, R.; Sidney, J.; Arlehamn, C.S.L.; Grifoni, A.; Dhanda, S.K.; Paul, S.; Peters, B.; Weiskopf, D.; Sette, A. A review on T Cell epitopes identified using prediction and cell-mediated immune models for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Bordetella pertussis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Antunes, R.; Quiambao, L.G.; Sutherland, A.; Soldevila, F.; Dhanda, S.K.; Armstrong, S.K.; Brickman, T.J.; Merkel, T.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. Development and Validation of a Bordetella pertussis Whole-Genome Screening Strategy. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 8202067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holubová, J.; Staněk, O.; Brázdilová, L.; Mašín, J.; Bumba, L.; Gorringe, A.R.; Alexander, F.; Šebo, P. Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Inhibits Bordetella pertussis Clearance from the Nasal Mucosa of Mice. Vaccines 2020, 8, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diavatopoulos, D.A.; Edwards, K.M. What is wrong with pertussis vaccine immunity? Why immunological memory to pertussis is failing. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a029553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeven, R.H.; van der Maas, L.; Tilstra, W.; Uittenbogaard, J.P.; Bindels, T.H.; Kuipers, B.; van der Ark, A.; Pennings, J.L.; van Riet, E.; Jiskoot, W.; et al. Immunoproteomic Profiling of Bordetella pertussis Outer Membrane Vesicle Vaccine Reveals Broad and Balanced Humoral Immunogenicity. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 2929–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkoff, A.M.; He, Q. Molecular Epidemiology of Bordetella pertussis. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 1183, pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mooi, F.R.; Van Der Maas, N.A.T.; De Melker, H.E. Pertussis resurgence: Waning immunity and pathogen adaptation—Two sides of the same coin. Epidemiol. Infect. 2014, 142, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, K.; Seymour, E.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. Substantial gaps in knowledge of Bordetella pertussis antibody and T cell epitopes relevant for natural immunity and vaccine efficacy. Hum. Immunol. 2014, 75, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mooi, F.R.; Van Oirschot, H.; Heuvelman, K.; Van der Heide, H.G.J.; Gaastra, W.; Willems, R.J.L. Polymorphism in the Bordetella pertussis virulence factors P.69/pertactin and pertussis toxin in The Netherlands: Temporal trends and evidence for vaccine-driven evolution. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; Octavia, S.; Bahrame, Z.; Sintchenko, V.; Gilbert, G.L.; Lan, R. Selection and emergence of pertussis toxin promoter ptxP3 allele in the evolution of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012, 12, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breakwell, L.; Kelso, P.; Finley, C.; Schoenfeld, S.; Goode, B.; Misegades, L.K.; Martin, S.W.; Acosta, A.M. Pertussis vaccine effectiveness in the setting of pertactin-deficient pertussis. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20153973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotkin, S.A. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotkin, S.A.; Gilbert, P.B. Nomenclature for immune correlates of protection after vaccination. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1615–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taranger, J.; Trollfors, B.; Lagergård, T.; Sundh, V.; Bryla, D.A.; Schneerson, R.; Robbins, J.B. Correlation between Pertussis Toxin IgG Antibodies in Postvaccination Sera and Subsequent Protection against Pertussis. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 181, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ausiello, C.M.; Lande, R.; Stefanelli, P.; Fazio, C.; Fedele, G.; Palazzo, R.; Urbani, F.; Mastrantonio, P. T-cell immune response assessment as a complement to serology and intranasal protection assays in determining the protective immunity induced by acellular pertussis vaccines in mice. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2003, 10, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassone, A.; Mastrantonio, P.; Ausiello, C.M. Are Only Antibody Levels Involved in the Protection against Pertussis in Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Recipients? J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 182, 1575–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Giacomini, E.; Urbani, F.; Ausiello, C.M.; Luzzati, A.L. Induction of a specific antibody response to Bordetella pertussis antigens in cultures of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 1999, 48, 1081–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhead, K.; Watkins, J.; Barnard, A.; Mills, K.H.G. Effective immunization against Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in mice is dependent on induction of cell-mediated immunity. Infect. Immun. 1993, 61, 3190–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plotkin, S.A. Composition of pertussis vaccine given to infants determines long-term T cell polarization. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3742–3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahon, B.P.; Brady, M.T.; Mills, K.H.G. Protection against Bordetella pertussis in mice in the absence of detectable circulating antibody: Implications for long-term immunity in children. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 181, 2087–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leef, M.; Elkins, K.L.; Barbic, J.; Shahin, R.D. Protective immunity to Bordetella pertussis requires both B cells and CD4+ T cells for key functions other than specific antibody production. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 191, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, P.J.; Sutton, C.E.; Higgins, S.; Allen, A.C.; Walsh, K.; Misiak, A.; Lavelle, E.C.; McLoughlin, R.M.; Mills, K.H.G.G. Relative Contribution of Th1 and Th17 Cells in Adaptive Immunity to Bordetella pertussis: Towards the Rational Design of an Improved Acellular Pertussis Vaccine. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.H.G.; Redhead, K. Cellular immunity in pertussis. J. Med. Microbiol. 1993, 39, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahon, B.P.; Sheahan, B.J.; Griffin, F.; Murphy, G.; Mills, K.H.G. Atypical disease after Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection of mice with targeted disruptions of interferon-γ receptor or imnaunoglobulin μ chain genes. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 186, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.H.; Brady, M.; Ryan, E.; Mahon, B.P. A respiratory challenge model for infection with Bordetella pertussis: Application in the assessment of pertussis vaccine potency and in defining the mechanism of protective immunity. Dev. Biol. Stand. 1998, 95, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K.H.G.; Ryan, M.; Ryan, E.; Mahon, B.P. A murine model in which protection correlates with pertussis vaccine efficacy in children reveals complementary roles for humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection against Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcguirk, P.; Mills, K.H.G. A regulatory role for interleukin 4 in differential inflammatory responses in the lung following infection of mice primed with Th1- or Th2- inducing pertussis vaccines. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbic, J.; Leef, M.F.; Burns, D.L.; Shahin, R.D. Role of gamma interferon in natural clearance of Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 4904–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, A.; Ross, P.J.; Pospisilova, E.; Masin, J.; Meaney, A.; Sutton, C.E.; Iwakura, Y.; Tschopp, J.; Sebo, P.; Mills, K.H.G. Inflammasome Activation by Adenylate Cyclase Toxin Directs Th17 Responses and Protection against Bordetella pertussis. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 1711–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Hester, S.E.; Kennett, M.J.; Karanikas, A.T.; Bendor, L.; Place, D.E.; Harvill, E.T. Interleukin-1 receptor signaling is required to overcome the effects of pertussis toxin and for efficient infection-or vaccination-induced immunity against Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiso, N.; Capiau, C.; Carletti, G.; Poolman, J.; Hauser, P. Intranasal murine model of Bordetella pertussis infection. I. Prediction of protection in human infants by acellular vaccines. Vaccine 1999, 17, 2366–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queenan, A.M.; Fernandez, J.; Shang, W.; Wiertsema, S.; Van Den Dobbelsteen, G.P.J.M.; Poolman, J. The mouse intranasal challenge model for potency testing of whole-cell pertussis vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2014, 13, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.H. Immunity to Bordetella pertussis. Microbes Infect. 2001, 3, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, C.; Powell, D.A.; Carbonetti, N.H. Pertussis toxin stimulates IL-17 production in response to Bordetella pertussis infection in mice. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muruganandah, V.; Sathkumara, H.D.; Navarro, S.; Kupz, A. A systematic review: The role of resident memory T cells in infectious diseases and their relevance for vaccine development. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, M.M.; Misiak, A.; McManus, R.M.; Allen, A.C.; Lynch, M.A.; Mills, K.H.G. Lung CD4 Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Mediate Adaptive Immunity Induced by Previous Infection of Mice with Bordetella pertussis. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak, A.; Wilk, M.M.; Raverdeau, M.; Mills, K.H.G. IL-17–Producing Innate and Pathogen-Specific Tissue Resident Memory γδ T Cells Expand in the Lungs of Bordetella pertussis-Infected Mice. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, M.M.; Borkner, L.; Misiak, A.; Curham, L.; Allen, A.C.; Mills, K.H.G. Immunization with whole cell but not acellular pertussis vaccines primes CD4 TRM cells that sustain protective immunity against nasal colonization with Bordetella pertussis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlon, K.M.; Snyder, Y.G.; Skerry, C.; Carbonetti, N.H. Fatal pertussis in the neonatal mouse model is associated with pertussis toxin-mediated pathology beyond the airways. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85, e00355-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, M.V.; Merkel, T.J. Pertussis disease and transmission and host responses: Insights from the baboon model of pertussis. J. Infect. 2017, 74, S114–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfel, J.M.; Beren, J.; Kelly, V.K.; Lee, G.; Merkel, T.J. Nonhuman Primate Model of Pertussis. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 1530–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, T.J.; Halperin, S.A. Nonhuman primate and human challenge models of pertussis. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, S20–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfel, J.M.; Merkel, T.J. The baboon model of pertussis: Effective use and lessons for pertussis vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2014, 13, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfel, J.M.; Papin, J.F.; Wolf, R.F.; Zimmerman, L.I.; Merkel, T.J. Maternal and neonatal vaccination protects newborn baboons from pertussis infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfel, J.M.; Zimmerman, L.I.; Merkel, T.J. Comparison of Three Whole-Cell Pertussis Vaccines in the Baboon Model of Pertussis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2016, 23, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfel, J.M.; Beren, J.; Merkel, T.J. Airborne Transmission of Bordetella pertussis. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 206, 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.H.G.; Gerdts, V. Mouse and Pig Models for Studies of Natural and Vaccine-Induced Immunity to Bordetella pertussis. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, S16–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.; Brownlie, R.; Korzeniowski, J.; Buchanan, R.; O’Connor, B.; Peppler, M.S.; Halperin, S.A.; Lee, S.F.; Babiuk, L.A.; Gerdts, V. Infection of newborn piglets with Bordetella pertussis: A new model for pertussis. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 3636–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepp, F.; Knuf, M.; Habermehl, P.; Schmitt, H.J.; Rebsch, C.; Schmidtke, P.; Clemens, R.; Slaoui, M. Pertussis-specific cell-mediated immunity in infants after vaccination with a tricomponent acellular pertussis vaccine. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 4078–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ausiello, C.M.; Lande, R.; Urbani, F.; La Sala, A.; Stefanelli, P.; Salmaso, S.; Mastrantonio, P.; Cassone, A. Cell-mediated immune responses in four-year-old children after primary immunization with acellular pertussis vaccines. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 4064–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, N.; Njamkepo, E.; Vié le Sage, F.; Zepp, F.; Meyer, C.U.; Abitbol, V.; Clyti, N.; Chevallier, S. Long-term humoral and cell-mediated immunity after acellular pertussis vaccination compares favourably with whole-cell vaccines 6 years after booster vaccination in the second year of life. Vaccine 2007, 25, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepp, F.; Knuf, M.; Habermehl, P.; Schmitt, H.J.; Meyer, C.; Clemens, R.; Slaoui, M. Cell-mediated immunity after pertussis vaccination and after natural infection. Dev. Biol. Stand. 1997, 89, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schure, R.-M.; Hendrikx, L.H.; de Rond, L.G.H.; Oztürk, K.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.-M. Differential T- and B-cell responses to pertussis in acellular vaccine-primed versus whole-cell vaccine-primed children 2 years after preschool acellular booster vaccination. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2013, 20, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schure, R.-M.; Hendrikx, L.H.; de Rond, L.G.H.; Öztürk, K.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.-M. T-Cell Responses before and after the Fifth Consecutive Acellular Pertussis Vaccination in 4-Year-Old Dutch Children. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, M.; Pandolfi, E.; Tozzi, A.E.; Buisman, A.-M.M.; Mascart, F.; Ausiello, C.M. Humoral and B-cell memory responses in children five years after pertussis acellular vaccine priming. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2093–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, K.; Pottier, G.; Smet, J.; Dirix, V.; Vermeulen, F.; De Schutter, I.; Carollo, M.; Locht, C.; Ausiello, C.M.; Mascart, F. Different T cell memory in preadolescents after whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccination. Vaccine 2013, 32, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadugba, O.O.; Wang, L.; Chen, Q.; Halasa, N.B. Immune responses to pertussis antigens in infants and toddlers after immunization with multicomponent acellular pertussis vaccine. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2014, 21, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rond, L.; Schure, R.M.; Öztürk, K.; Berbers, G.; Sanders, E.; Van Twillert, I.; Carollo, M.; Mascart, F.; Ausiello, C.M.; Van Els, C.A.C.M.; et al. Identification of pertussis-specific effector memory T cells in preschool children. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2015, 22, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dirix, V.; Verscheure, V.; Goetghebuer, T.; Hainaut, M.; Debrie, A.S.; Locht, C.; Mascart, F. Cytokine and antibody profiles in 1-year-old children vaccinated with either acellular or whole-cell pertussis vaccine during infancy. Vaccine 2009, 27, 6042–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, E.J.; Nilsson, L.; Kjellman, N.; Gothefors, L.; Mills, K.H. Booster immunization of children with an acellular pertussis vaccine enhances Th2 cytokine production and serum IgE responses against pertussis toxin but not against common allergens. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2000, 121, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascart, F.; Hainaut, M.; Peltier, A.; Verscheure, V.; Levy, J.; Locht, C. Modulation of the infant immune responses by the first pertussis vaccine administrations. Vaccine 2007, 25, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, J.; van Schuppen, E.; Diavatopoulos, D.A. Functional Programming of Innate Immune Cells in Response to Bordetella pertussis Infection and Vaccination. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 1183, pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikx, L.H.; Schure, R.M.; Öztürk, K.; de Rond, L.G.H.; de Greeff, S.C.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.M. Different IgG-subclass distributions after whole-cell and acellular pertussis infant primary vaccinations in healthy and pertussis infected children. Vaccine 2011, 29, 6874–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Antunes, R.; Babor, M.; Carpenter, C.; Khalil, N.; Cortese, M.; Mentzer, A.J.; Seumois, G.; Petro, C.D.; Purcell, L.A.; Vijayanand, P.; et al. Th1/Th17 polarization persists following whole-cell pertussis vaccination despite repeated acellular boosters. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3853–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieber, N.; Graf, A.; Hartl, D.; Urschel, S.; Belohradsky, B.H.; Liese, J. Acellular pertussis booster in adolescents induces Th1 and memory CD8+ T cell immune response. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitkara, A.J.; Pujadas Ferrer, M.; Forsyth, K.; Guiso, N.; Heininger, U.; Hozbor, D.F.; Muloiwa, R.; Tan, T.Q.; Thisyakorn, U.; Wirsing von König, C.H. Pertussis vaccination in mixed markets: Recommendations from the Global Pertussis Initiative. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 96, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, R.; Carollo, M.; Bianco, M.; Fedele, G.; Schiavoni, I.; Pandolfi, E.; Villani, A.; Tozzi, A.E.; Mascart, F.; Ausiello, C.M. Persistence of T-cell immune response induced by two acellular pertussis vaccines in children five years after primary vaccination. New Microbiol. 2016, 39, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, R.; Kunkel, E.; Crowcroft, N.S.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; De Melker, H.; Althouse, B.M.; Merkel, T.; Scarpino, S.V.; Koelle, K.; Friedman, L.; et al. Asymptomatic Infection and Transmission of Pertussis in Households: A Systematic Review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 70, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deville, J.G.; Cherry, J.D.; Christenson, P.D.; Pineda, E.; Leach, C.T.; Kuhls, T.L.; Viker, S. Frequency of unrecognized Bordetella pertussis infections in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 21, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deen, J.L.; Mink, C.M.; Cherry, J.D.; Christenson, P.D.; Pineda, E.F.; Lewis, K.; Blumberg, D.A.; Ross, L.A. Household contact study of Bordetella pertussis infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 21, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.P.; Deng, T.Z.; Witherden, D.A.; Goldrath, A.W. Origins of CD4+ circulating and tissue-resident memory T-cells. Immunology 2019, 157, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindenstrøm, T.; Woodworth, J.; Dietrich, J.; Aagaard, C.; Andersen, P.; Agger, E.M. Vaccine-induced Th17 cells are maintained long-term postvaccination as a distinct and phenotypically stable memory subset. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 3533–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korn, T.; Bettelli, E.; Oukka, M.; Kuchroo, V.K. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 27, 485–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffar, Z.; Ferrini, M.E.; Herritt, L.A.; Roberts, K. Cutting Edge: Lung Mucosal Th17-Mediated Responses Induce Polymeric Ig Receptor Expression by the Airway Epithelium and Elevate Secretory IgA Levels. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 4507–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomanen, E.I.; Zapiain, L.A.; Galvan, P.; Hewlett, E.L. Characterization of antibody inhibiting adherence of Bordetella pertussis to human respiratory epithelial cells. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1984, 20, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, S. T follicular helper cell differentiation, function, and roles in disease. Immunity 2014, 41, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, S. T Follicular Helper Cell Biology: A Decade of Discovery and Diseases. Immunity 2019, 50, 1132–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Ramirez, J.C.; Carey, M.; Miao, H.; Arias, C.A.; Rice, A.P.; Wu, H. Investigation of temporal and spatial heterogeneities of the immune responses to Bordetella pertussis infection in the lung and spleen of mice via analysis and modeling of dynamic microarray gene expression data. Infect. Dis. Model. 2019, 4, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx, L.H.; De Rond, L.G.H.; Öztürk, K.; Veenhoven, R.H.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.-M.M. Impact of infant and preschool pertussis vaccinations on memory B-cell responses in children at 4 years of age. Vaccine 2011, 29, 5725–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrikx, L.H.; Felderhof, M.K.; Öztürk, K.; de Rond, L.G.H.; van Houten, M.A.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.-M.M. Enhanced memory B-cell immune responses after a second acellular pertussis booster vaccination in children 9 years of age. Vaccine 2011, 30, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenger, R.M.; Smits, M.; Kuipers, B.; van Gaans-van den Brink, J.; Poelen, M.; Boog, C.J.P.; van Els, C.A.C.M. Impaired long-term maintenance and function of Bordetella pertussis specific B cell memory. Vaccine 2010, 28, 6637–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrikx, L.H.; Öztürk, K.; de Rond, L.G.H.; Veenhoven, R.H.; Sanders, E.A.M.; Berbers, G.A.M.; Buisman, A.-M.M. Identifying long-term memory B-cells in vaccinated children despite waning antibody levels specific for Bordetella pertussis proteins. Vaccine 2011, 29, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkoff, A.M.; Gröndahl-Yli-Hannuksela, K.; Vuononvirta, J.; Mertsola, J.; Kallonen, T.; He, Q. Differences in avidity of IgG antibodies to pertussis toxin after acellular pertussis booster vaccination and natural infection. Vaccine 2012, 30, 6897–6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, S.F.; Persson Berg, L.; Olsen Ekerhult, T.; Rimkute, I.; Wick, M.-J.; Mårtensson, I.-L.; Grimsholm, O. Long-Lived Plasma Cells in Mice and Men. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirix, V.; Verscheure, V.; Vermeulen, F.; De Schutter, I.; Goetghebuer, T.; Locht, C.; Mascart, F. Both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes participate in the IFN-γ response to filamentous hemagglutinin from Bordetella pertussis in infants, children, and adults. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 795958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, H.; Gbesemete, D.; Gorringe, A.R.; Diavatopoulos, D.A.; Kester, K.E.; Faust, S.N.; Read, R.C. Investigating Bordetella pertussis colonisation and immunity: Protocol for an inpatient controlled human infection model. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, H.; Ibrahim, M.; Hill, A.; Gbesemete, D.; Gorringe, A.; Diavatopoulos, D.; Kester, K.; Berbers, G.; Faust, S.; Read, R. 167. A Bordetella pertussis Human Challenge Model Induces Immunizing Colonization in the Absence of Symptoms. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmann, T.R.; Kampmann, B.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Marchant, A.; Levy, O. Protecting the Newborn and Young Infant from Infectious Diseases: Lessons from Immune Ontogeny. Immunity 2017, 46, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saso, A.; Kampmann, B. Vaccine responses in newborns. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, B.B.; Jagne, Y.J.; Armitage, E.P.; Singanayagam, A.; Sallah, H.J.; Drammeh, S.; Senghore, E.; Mohammed, N.I.; Jeffries, D.; Höschler, K.; et al. Effect of a Russian-backbone live-attenuated influenza vaccine with an updated pandemic H1N1 strain on shedding and immunogenicity among children in The Gambia: An open-label, observational, phase 4 study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, M.; Palazzo, R.; Bianco, M.; Smits, K.; Mascart, F.; Ausiello, C.M. Antigen-specific responses assessment for the evaluation of Bordetella pertussis T cell immunity in humans. Vaccine 2012, 30, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, C.R.; Jones, C.E. Beyond passive immunity: Is there priming of the fetal immune system following vaccination in pregnancy and what are the potential clinical implications? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaxman, A.; Ewer, K.J. Methods for measuring T-cell memory to vaccination: From mouse to man. Vaccines 2018, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobeika, A.C.; Morse, M.A.; Osada, T.; Ghanayem, M.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Barrier, R.; Lyerly, H.K.; Clay, T.M. Enumerating antigen-specific t-cell responses in peripheral blood: A comparison of peptide MHC tetramer, ELISpot, and intracellular cytokine analysis. J. Immunother. 2005, 28, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, F.; Gorski, S.A.; Petrovsky, N. Pushing the frontiers of T-cell vaccines: Accurate measurement of human T-cell responses. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2012, 11, 1459–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Blasi, D.; Claessen, I.; Turksma, A.W.; van Beek, J.; ten Brinke, A. Guidelines for analysis of low-frequency antigen-specific T cell results: Dye-based proliferation assay vs 3H-thymidine incorporation. J. Immunol. Methods 2020, 487, 112907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messele, T.; Roos, M.T.L.; Hamann, D.; Koot, M.; Fontanet, A.L.; Miedema, F.; Schellekens, P.T.A.; Rinke De Wit, T.F. Nonradioactive techniques for measurement of in vitro t-cell proliferation alternatives to the [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2000, 7, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahnmatz, M.; Kesa, G.; Netterlid, E.; Buisman, A.M.; Thorstensson, R.; Ahlborg, N. Optimization of a human IgG B-cell ELISpot assay for the analysis of vaccine-induced B-cell responses. J. Immunol. Methods 2013, 391, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slota, M.; Lim, J.B.; Dang, Y.; Disis, M.L. ELISpot for measuring human immune responses to vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2011, 10, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janetzki, S.; Rueger, M.; Dillenbeck, T. Stepping up ELISpot: Multi-Level Analysis in FluoroSpot Assays. Cells 2014, 3, 1102–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phetsouphanh, C.; Zaunders, J.J.; Kelleher, A.D. Detecting antigen-specific T cell responses: From bulk populations to single cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18878–18893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.B. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J. Immunol. Methods 2000, 243, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.; Govender, L.; Hughes, J.; Mavakla, W.; de Kock, M.; Barnard, C.; Pienaar, B.; Janse van Rensburg, E.; Jacobs, G.; Khomba, G.; et al. Novel application of Ki67 to quantify antigen-specific in vitro lymphoproliferation. J. Immunol. Methods 2010, 362, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roederer, M.; Brenchley, J.M.; Betts, M.R.; De Rosa, S.C. Flow cytometric analysis of vaccine responses: How many colors are enough? Clin. Immunol. 2004, 110, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, E.E.; Corbière, V.; van Gaans-Van den Brink, J.A.M.; Duijst, M.; Venkatasubramanian, P.B.; Simonetti, E.; Huynen, M.; Diavatopoulos, D.D.; Versteegen, P.; Berbers, G.A.M.; et al. Uncovering distinct primary vaccination-dependent profiles in human Bordetella pertussis specific cd4+ t-cell responses using a novel whole blood assay. Vaccines 2020, 8, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercovici, N.; Duffour, M.T.; Agrawal, S.; Salcedo, M.; Abastado, J.P. New methods for assessing T-cell responses. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2000, 7, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowyer, G.; Rampling, T.; Powlson, J.; Morter, R.; Wright, D.; Hill, A.; Ewer, K. Activation-induced Markers Detect Vaccine-Specific CD4+ T Cell Responses Not Measured by Assays Conventionally Used in Clinical Trials. Vaccines 2018, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S.; Willberg, C.; Klenerman, P. MHC-peptide tetramers for the analysis of antigen-specific T cells. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2010, 9, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddiki, N.; Cook, L.; Hsu, D.C.; Phetsouphanh, C.; Brown, K.; Xu, Y.; Kerr, S.J.; Cooper, D.A.; Munier, C.M.L.; Pett, S.; et al. Human antigen-specific CD4+CD25+CD134+CD39+ T cells are enriched for regulatory T cells and comprise a substantial proportion of recall responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 1644–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, J.M.; Lindestam Arlehamn, C.S.; Weiskopf, D.; da Silva Antunes, R.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; Reiss, S.M.; Brigger, M.; Bothwell, M.; Sette, A.; Crotty, S. A Cytokine-Independent Approach To Identify Antigen-Specific Human Germinal Center T Follicular Helper Cells and Rare Antigen-Specific CD4+ T Cells in Blood. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, S.; Baxter, A.E.; Cirelli, K.M.; Dan, J.M.; Morou, A.; Daigneault, A.; Brassard, N.; Silvestri, G.; Routy, J.-P.; Havenar-Daughton, C.; et al. Comparative analysis of activation induced marker (AIM) assays for sensitive identification of antigen-specific CD4 T cells. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, P.K.; Yu, J.; Roederer, M. Live-cell assay to detect antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell responses by CD154 expression. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frentsch, M.; Arbach, O.; Kirchhoff, D.; Moewes, B.; Worm, M.; Rothe, M.; Scheffold, A.; Thiel, A. Direct access to CD4+ T cells specific for defined antigens according to CD154 expression. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfl, M.; Kuball, J.; Ho, W.Y.; Nguyen, H.; Manley, T.J.; Bleakley, M.; Greenberg, P.D. Activation-induced expression of CD137 permits detection, isolation, and expansion of the full repertoire of CD8+ T cells responding to antigen without requiring knowledge of epitope specificities. Blood 2007, 110, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacher, P.; Schink, C.; Teutschbein, J.; Kniemeyer, O.; Assenmacher, M.; Brakhage, A.A.; Scheffold, A. Antigen-Reactive T Cell Enrichment for Direct, High-Resolution Analysis of the Human Naive and Memory Th Cell Repertoire. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 3967–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, R.; Duhen, T.; Lanzavecchia, A.; Sallusto, F. Human naive and memory CD4+ T cell repertoires specific for naturally processed antigens analyzed using libraries of amplified T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifoni, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Ramirez, S.I.; Mateus, J.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Rawlings, S.A.; Sutherland, A.; Premkumar, L.; Jadi, R.S.; et al. Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell 2020, 181, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, P.M.; Sluder, A.E.; Paul, S.R.; Scholzen, A.; Kashiwagi, S.; Poznansky, M.C. Application and utility of mass cytometry in vaccine development. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Maecker, H.T. Mass cytometry assays for antigen-specific T cells using CyTOF. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press Inc.: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2018; Volume 1678, pp. 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Brummelman, J.; Raeven, R.H.M.; Helm, K.; Pennings, J.L.A.; Metz, B.; Van Eden, W.; Van Els, C.A.C.M.; Han, W.G.H. Transcriptome signature for dampened Th2 dominance in acellular pertussis vaccine-induced CD4+ T cell responses through TLR4 ligation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeven, R.H.M.; Brummelman, J.; Pennings, J.L.A.; Nijst, O.E.M.; Kuipers, B.; Blok, L.E.R.; Helm, K.; Van Riet, E.; Jiskoot, W.; Van Els, C.A.C.M.; et al. Molecular signatures of the evolving immune response in mice following a Bordetella pertussis infection. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, O.J.; McKenna, K.L.; Bosco, A.; van den Biggelaar, A.H.J.; Richmond, P.; Holt, P.G. A genomics-based approach to assessment of vaccine safety and immunogenicity in children. Vaccine 2012, 30, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raeven, R.H.M.; Brummelman, J.; La Pennings, J.; Van Der Maas, L.; Helm, K.; Tilstra, W.; Van Der Ark, A.; Sloots, A.; Van Der Ley, P.; Van Eden, W.; et al. Molecular and cellular signatures underlying superior immunity against Bordetella pertussis upon pulmonary vaccination. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 979–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnik, J.E.; Egli, A. Impact of host genetic polymorphisms on vaccine induced antibody response. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezeshki, A.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; McKinney, B.A.; Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B. The role of systems biology approaches in determining molecular signatures for the development of more effective vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2019, 18, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afik, S.; Yates, K.B.; Bi, K.; Darko, S.; Godec, J.; Gerdemann, U.; Swadling, L.; Douek, D.C.; Klenerman, P.; Barnes, E.J.; et al. Targeted reconstruction of T cell receptor sequence from single cell RNA-seq links CDR3 length to T cell differentiation state. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, K. Can We Improve Vaccine Efficacy by Targeting T and B Cell Repertoire Convergence? Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noé, A.; Cargill, T.N.; Nielsen, C.M.; Russell, A.J.C.; Barnes, E. The Application of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Vaccinology. J. Immunol. Res. 2020, 2020, 8624963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruiswijk, C.; Richard, G.; Salverda, M.L.M.; Hindocha, P.; Martin, W.D.; De Groot, A.S.; Van Riet, E. In silico identification and modification of T cell epitopes in pertussis antigens associated with tolerance. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bart, M.J.; van Gent, M.; van der Heide, H.G.J.; Boekhorst, J.; Hermans, P.; Parkhill, J.; Mooi, F.R. Comparative genomics of prevaccination and modern Bordetella pertussis strains. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochems, S.P.; Piddock, K.; Rylance, J.; Adler, H.; Carniel, B.F.; Collins, A.; Gritzfeld, J.F.; Hancock, C.; Hill, H.; Reiné, J.; et al. Novel Analysis of Immune Cells from Nasal Microbiopsy Demonstrates Reliable, Reproducible Data for Immune Populations, and Superior Cytokine Detection Compared to Nasal Wash. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, T.I.; Gould, V.; Mohammed, N.I.; Cope, A.; Meijer, A.; Zutt, I.; Reimerink, J.; Kampmann, B.; Hoschler, K.; Zambon, M.; et al. Comparison of mucosal lining fluid sampling methods and influenza-specific IgA detection assays for use in human studies of influenza immunity. J. Immunol. Methods 2017, 449, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scadding, G.W.; Calderon, M.A.; Bellido, V.; Koed, G.K.; Nielsen, N.-C.; Lund, K.; Togias, A.; Phippard, D.; Turka, L.A.; Hansel, T.T.; et al. Optimisation of grass pollen nasal allergen challenge for assessment of clinical and immunological outcomes. J. Immunol. Methods 2012, 384, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thwaites, R.S.; Coates, M.; Ito, K.; Ghazaly, M.; Feather, C.; Abdulla, F.; Tunstall, T.; Jain, P.; Cass, L.; Rapeport, G.; et al. Reduced Nasal Viral Load and IFN Responses in Infants with Respiratory Syncytial Virus Bronchiolitis and Respiratory Failure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thwaites, R.S.; Ito, K.; Chingono, J.M.S.; Coates, M.; Jarvis, H.C.; Tunstall, T.; Anderson-Dring, L.; Cass, L.; Rapeport, G.; Openshaw, P.J.; et al. Nasosorption as a minimally invasive sampling procedure: Mucosal viral load and inflammation in primary RSV bronchiolitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 1240–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, R.S.; Jarvis, H.C.; Singh, N.; Jha, A.; Pritchard, A.; Fan, H.; Tunstall, T.; Nanan, J.; Nadel, S.; Kon, O.M.; et al. Absorption of nasal and bronchial fluids: Precision sampling of the human respiratory mucosa and laboratory processing of samples. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 2018, 56413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.O.; Kupper, T.S. The emerging role of resident memory T cells in protective immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. Factors that influence the immune response to vaccination. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00084-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, F.; Verscheure, V.; Damis, E.; Vermeylen, D.; Leloux, G.; Dirix, V.; Locht, C.; Mascart, F. Cellular immune responses of preterm infants after vaccination with whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccines. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, C.A. The Challenges of Vaccine Responses in Early Life: Selected Examples. J. Comp. Pathol. 2007, 137, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, O. Innate immunity of the newborn: Basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegrist, C.A.; Aspinall, R. B-cell responses to vaccination at the extremes of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, M.E.; Miller, E.; Ashworth, L.A.E.; Coleman, T.J.; Rush, M.; Waight, P.A. Adverse events and antibody response to accelerated immunisation in term and preterm infants. Arch. Dis. Child. 1995, 72, 230–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, M.H.; Schapira, D.; Thwaites, R.J.; Burrage, M.; Southern, J.; Goldblatt, D.; Miller, E. Responses to a fourth dose of Haemophilus influenzae type B conjugate vaccine in early life. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004, 89, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloesser, R.L.; Fischer, D.; Otto, W.; Rettwitz-Volk, W.; Herden, P.; Zielen, S. Safety and immunogenicity of an acellular pertussis vaccine in premature infants. Pediatrics 1999, 103, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischinger, S.; Boudreau, C.M.; Butler, A.L.; Streeck, H.; Alter, G. Sex differences in vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, I.; Dejager, L.; Libert, C. X-chromosome-located microRNAs in immunity: Might they explain male/female differences? BioEssays 2011, 33, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newport, M.J.; Goetghebuer, T.; Weiss, H.A.; Allen, A.; Banya, W.; Sillah, D.J.; McAdam, K.P.W.J.; Mendy, M.; Ota, M.; Vekemans, J.; et al. Genetic regulation of immune responses to vaccines in early life. Genes Immun. 2004, 5, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newport, M.J. The genetic regulation of infant immune responses to vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newport, M.J.; Goetghebuer, T.; Marchant, A. Hunting for immune response regulatory genes: Vaccination studies in infant twins. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2005, 4, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yucesoy, B.; Talzhanov, Y.; Johnson, V.J.; Wilson, N.W.; Biagini, R.E.; Wang, W.; Frye, B.; Weissman, D.N.; Germolec, D.R.; Luster, M.I.; et al. Genetic variants within the MHC region are associated with immune responsiveness to childhood vaccinations. Vaccine 2013, 31, 5381–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yucesoy, B.; Johnson, V.J.; Fluharty, K.; Kashon, M.L.; Slaven, J.E.; Wilson, N.W.; Weissman, D.N.; Biagini, R.E.; Germolec, D.R.; Luster, M.I. Influence of cytokine gene variations on immunization to childhood vaccines. Vaccine 2009, 27, 6991–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhiman, N.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Vierkant, R.A.; Ryan, J.E.; Shane Pankratz, V.; Jacobson, R.M.; Poland, G.A. Associations between SNPs in toll-like receptors and related intracellular signaling molecules and immune responses to measles vaccine: Preliminary results. Vaccine 2008, 26, 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Dhiman, N.; Haralambieva, I.H.; Vierkant, R.A.; O’Byrne, M.M.; Jacobson, R.M.; Poland, G.A. Rubella vaccine-induced cellular immunity: Evidence of associations with polymorphisms in the Toll-like, vitamin A and D receptors, and innate immune response genes. Hum. Genet. 2010, 127, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooling, L. Blood groups in infection and host susceptibility. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 801–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banus, S.; Bottema, R.W.B.; Siezen, C.L.E.; Vandebriel, R.J.; Reimerink, J.; Mommers, M.; Koppelman, G.H.; Hoebee, B.; Thijs, C.; Postma, D.S.; et al. Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphism associated with the response to whole-cell pertussis vaccination in children from the KOALA study. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2007, 14, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciabattini, A.; Olivieri, R.; Lazzeri, E.; Medaglini, D. Role of the microbiota in the modulation of vaccine immune responses. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, D.J.; Pulendran, B. The potential of the microbiota to influence vaccine responses. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018, 103, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barko, P.C.; McMichael, M.A.; Swanson, K.S.; Williams, D.A. The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: A Review. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borkner, L.; Misiak, A.; Wilk, M.M.; Mills, K.H.G. Azithromycin Clears Bordetella pertussis Infection in Mice but Also Modulates Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses and T Cell Memory. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ran, Z.; Tian, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J.; Yin, J.; Lu, D.; Li, R.; Zhong, J. Commensal microbes affect host humoral immunity to Bordetella pertussis infection. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00421-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabichi, Y.; Li, K.; Hu, S.; Nguyen, C.; Wang, X.; Elashoff, D.; Saira, K.; Frank, B.; Bihan, M.; Ghedin, E.; et al. The administration of intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine induces changes in the nasal microbiota and nasal epithelium gene expression profiles. Microbiome 2015, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Gordon, A.; Shedden, K.; Kuan, G.; Ng, S.; Balmaseda, A.; Foxman, B. The respiratory microbiome and susceptibility to influenza virus infection. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0207898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mika, M.; Mack, I.; Korten, I.; Qi, W.; Aebi, S.; Frey, U.; Latzin, P.; Hilty, M. Dynamics of the nasal microbiota in infancy: A prospective cohort study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 905–912.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyrich, L.S.; Feaga, H.A.; Park, J.; Muse, S.J.; Safi, C.Y.; Rolin, O.Y.; Young, S.E.; Harvill, E.T. Resident microbiota affect Bordetella pertussis infectious dose and host specificity. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Janoff, E.N.; Gustafson, C.; Frank, D.N. The world within: Living with our microbial guests and guides. Transl. Res. 2012, 160, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Doare, K.; Holder, B.; Bassett, A.; Pannaraj, P.S. Mother’s Milk: A Purposeful Contribution to the Development of the Infant Microbiota and Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmiz, N.; Robinson, R.C.; Shah, I.M.; Barile, D.; Mills, D.A. Milk Glycans and Their Interaction with the Infant-Gut Microbiota. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gensollen, T.; Iyer, S.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Blumberg, R.S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016, 352, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pro, S.C.; Lindestam Arlehamn, C.S.; Dhanda, S.K.; Carpenter, C.; Lindvall, M.; Faruqi, A.A.; Santee, C.A.; Renz, H.; Sidney, J.; Peters, B.; et al. Microbiota epitope similarity either dampens or enhances the immunogenicity of disease-associated antigenic epitopes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mika, M.; Maurer, J.; Korten, I.; Allemann, A.; Aebi, S.; Brugger, S.D.; Qi, W.; Frey, U.; Latzin, P.; Hilty, M. Influence of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on the temporal variation of pneumococcal carriage and the nasal microbiota in healthy infants: A longitudinal analysis of a case–control study. Microbiome 2017, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, O.; Newell, M.L.; Jones, C.E. The effect of human immunodeficiency virus and Cytomegalovirus infection on infant responses to vaccines: A review. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, D.J.C.; van der Sande, M.; Jeffries, D.; Kaye, S.; Ismaili, J.; Ojuola, O.; Sanneh, M.; Touray, E.S.; Waight, P.; Rowland-Jones, S.; et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection in Gambian Infants Leads to Profound CD8 T-Cell Differentiation. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5766–5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendergast, A.J. Malnutrition and vaccination in developing countries. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2015, 370, 20140141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savy, M.; Edmond, K.; Fine, P.E.M.; Hall, A.; Hennig, B.J.; Moore, S.E.; Mulholland, K.; Schaible, U.; Prentice, A.M. Landscape analysis of interactions between nutrition and vaccine responses in children. J. Nutr. 2009, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadarangani, S.P.; Whitaker, J.A.; Poland, G.A. “Let there be light”: The role of Vitamin D in the immune response to vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, C.S.; Fisker, A.B.; Rieckmann, A.; Sørup, S.; Aaby, P. Vaccinology: Time to change the paradigm? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e274–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaayeb, L.; Pinçon, C.; Cames, C.; Sarr, J.B.; Seck, M.; Schacht, A.M.; Remoué, F.; Hermann, E.; Riveau, G. Immune response to Bordetella pertussis is associated with season and undernutrition in Senegalese children. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3431–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaby, P.; Martins, C.L.; Garly, M.L.; Balé, C.; Andersen, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Ravn, H.; Lisse, I.M.; Benn, C.S.; Whittle, H.C. Non-specific effects of standard measles vaccine at 4.5 and 9 months of age on childhood mortality: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010, 341, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, C.S.; Netea, M.G.; Selin, L.K.; Aaby, P. A Small Jab—A Big Effect: Nonspecific Immunomodulation By Vaccines. Trends Immunol. 2013, 34, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; van der Meer, J.W.M. Trained Immunity: An Ancient Way of Remembering. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bree, L.C.J.; Koeken, V.A.C.M.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Aaby, P.; Benn, C.S.; van Crevel, R.; Netea, M.G. Non-specific effects of vaccines: Current evidence and potential implications. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 39, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, N.L.; Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. The impact of vaccines on heterologous adaptive immunity. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadatian-Elahi, M.; Aaby, P.; Shann, F.; Netea, M.G.; Levy, O.; Louis, J.; Picot, V.; Greenberg, M.; Warren, W. Heterologous vaccine effects. In Proceedings of the Vaccine; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 34, pp. 3923–3930. [Google Scholar]

- Kiravu, A.; Osawe, S.; Happel, A.-U.; Nundalall, T.; Wendoh, J.; Beer, S.; Dontsa, N.; Alinde, O.B.; Mohammed, S.; Datong, P.; et al. Bacille Calmette-Guérin Vaccine Strain Modulates the Ontogeny of Both Mycobacterial-Specific and Heterologous T Cell Immunity to Vaccination in Infants. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidor, E. The Nature and Consequences of Intra- and Inter-Vaccine Interference. J. Comp. Pathol. 2007, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saso, A.; Kampmann, B. Maternal Immunization: Nature Meets Nurture. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanlapakorn, N.; Maertens, K.; Vongpunsawad, S.; Puenpa, J.; Tran, T.M.P.; Hens, N.; Van Damme, P.; Thiriard, A.; Raze, D.; Locht, C.; et al. Quantity and Quality of Antibodies After Acellular Versus Whole-cell Pertussis Vaccines in Infants Born to Mothers Who Received Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine During Pregnancy: A Randomized Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, M.; Arck, P.C. Vertically Transferred Immunity in Neonates: Mothers, Mechanisms and Mediators; Frontiers Media S.A.: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 11, p. 555. [Google Scholar]

- Voysey, M.; Kelly, D.F.; Fanshawe, T.R.; Sadarangani, M.; O’Brien, K.L.; Perera, R.; Pollard, A.J. The influence of maternally derived antibody and infant age at vaccination on infant vaccine responses: An individual participant meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vono, M.; Eberhardt, C.S.; Auderset, F.; Mastelic-Gavillet, B.; Lemeille, S.; Christensen, D.; Andersen, P.; Lambert, P.H.; Siegrist, C.A. Maternal Antibodies Inhibit Neonatal and Infant Responses to Vaccination by Shaping the Early-Life B Cell Repertoire within Germinal Centers. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1773–1784.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orije, M.R.P.; Maertens, K.; Corbière, V.; Wanlapakorn, N.; Van Damme, P.; Leuridan, E.; Mascart, F. The effect of maternal antibodies on the cellular immune response after infant vaccination: A review. Vaccine 2019, 38, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, L.; da Gama Fortunato Molina, M.; Pereira, B.S.; Nadaf, M.L.A.; Nadaf, M.I.V.; Takano, O.A.; Carneiro-Sampaio, M.; Palmeira, P. Acquisition of specific antibodies and their influence on cell-mediated immune response in neonatal cord blood after maternal pertussis vaccination during pregnancy. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinder, J.M.; Jiang, T.T.; Ertelt, J.M.; Xin, L.; Strong, B.S.; Shaaban, A.F.; Way, S.S. Cross-Generational Reproductive Fitness Enforced by Microchimeric Maternal Cells. Cell 2015, 162, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennewein, M.F.; Abu-Raya, B.; Jiang, Y.; Alter, G.; Marchant, A. Transfer of maternal immunity and programming of the newborn immune system. Semin. Immunopathol. 2017, 39, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinder, J.M.; Stelzer, I.A.; Arck, P.C.; Way, S.S. Immunological implications of pregnancy-induced microchimerism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinder, J.M.; Stelzer, I.A.; Arck, P.C.; Way, S.S. Reply: Breastfeeding-related maternal microchimerism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molès, J.P.; Tuaillon, E.; Kankasa, C.; Bedin, A.S.; Nagot, N.; Marchant, A.; McDermid, J.M.; Van De Perre, P. Breastfeeding-related maternal microchimerism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, I.; Dent, A.; Mungai, P.; Wamachi, A.; Ouma, J.H.; Narum, D.L.; Muchiri, E.; Tisch, D.J.; King, C.L. Can prenatal malaria exposure produce an immune tolerant phenotype?: A prospective birth cohort study in Kenya. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchant, A.; Sadarangani, M.; Garand, M.; Dauby, N.; Verhasselt, V.; Pereira, L.; Bjornson, G.; Jones, C.E.; Halperin, S.A.; Edwards, K.M.; et al. Maternal immunisation: Collaborating with mother nature. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e197–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauby, N.; Goetghebuer, T.; Kollmann, T.R.; Levy, J.; Marchant, A. Uninfected but not unaffected: Chronic maternal infections during pregnancy, fetal immunity, and susceptibility to postnatal infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Chamley, L.W. Placental extracellular vesicles and feto-maternal communication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a023028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labeaud, A.D.; Malhotra, I.; King, M.J.; King, C.L.; King, C.H. Do antenatal parasite infections devalue childhood vaccination? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009, 3, e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flügge, J.; Adegnika, A.A.; Honkpehedji, Y.J.; Sandri, T.L.; Askani, E.; Manouana, G.P.; Massinga Loembe, M.; Brückner, S.; Duali, M.; Strunk, J.; et al. Impact of Helminth Infections during Pregnancy on Vaccine Immunogenicity in Gabonese Infants. Vaccines 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, I.; McKibben, M.; Mungai, P.; McKibben, E.; Wang, X.; Sutherland, L.J.; Muchiri, E.M.; King, C.H.; King, C.L.; LaBeaud, A.D. Effect of Antenatal Parasitic Infections on Anti-vaccine IgG Levels in Children: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study in Kenya. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, S.; Mentzer, A.J.; Lule, S.A.; Kizito, D.; Smits, G.; van der Klis, F.R.M.; Elliott, A.M. The impact of prenatal exposure to parasitic infections and to anthelminthic treatment on antibody responses to routine immunisations given in infancy: Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, A.M.; Kizza, M.; Quigley, M.A.; Ndibazza, J.; Nampijja, M.; Muhangi, L.; Morison, L.; Namujju, P.B.; Muwanga, M.; Kabatereine, N.; et al. The impact of helminths on the response to immunization and on the incidence of infection and disease in childhood in Uganda: Design of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, factorial trial of deworming interventions delivered in pregnancy and early childhood. Clin. Trials 2007, 4, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, E.L.; Mawa, P.A.; Ndibazza, J.; Kizito, D.; Namatovu, A.; Kyosiimire-Lugemwa, J.; Nanteza, B.; Nampijja, M.; Muhangi, L.; Woodburn, P.W.; et al. Effect of single-dose anthelmintic treatment during pregnancy on an infant’s response to immunisation and on susceptibility to infectious diseases in infancy: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A.M.; Mawa, P.A.; Webb, E.L.; Nampijja, M.; Lyadda, N.; Bukusuba, J.; Kizza, M.; Namujju, P.B.; Nabulime, J.; Ndibazza, J.; et al. Effects of maternal and infant co-infections, and of maternal immunisation, on the infant response to BCG and tetanus immunisation. Vaccine 2010, 29, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidzeru, E.B.; Hesseling, A.C.; Passmore, J.A.S.; Myer, L.; Gamieldien, H.; Tchakoute, C.T.; Gray, C.M.; Sodora, D.L.; Jaspan, H.B. In-utero exposure to maternal HIV infection alters T-cell immune responses to vaccination in HIV-uninfected infants. AIDS 2014, 28, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hygino, J.; Lima, P.G.; Filho, R.G.S.; Silva, A.A.L.; Saramago, C.S.M.; Andrade, R.M.; Andrade, D.M.; Andrade, A.F.B.; Brindeiro, R.; Tanuri, A.; et al. Altered immunological reactivity in HIV-1-exposed uninfected neonates. Clin. Immunol. 2008, 127, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges-Almeida, E.; Milanez, H.M.B.P.M.; Vilela, M.M.S.; Cunha, F.G.P.; Abramczuk, B.M.; Reis-Alves, S.C.; Metze, K.; Lorand-Metze, I. The impact of maternal HIV infection on cord blood lymphocyte subsets and cytokine profile in exposed non-infected newborns. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, T.J.; Repetti, C.F.; Metlay, L.A.; Rabin, B.S.; Taylor, F.H.; Thompson, D.S.; Cortese, A.L. Transplacental immunization of the human fetus to tetanus by immunization of the mother. J. Clin. Investig. 1983, 72, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, D.; Wang, C.; Mao, X.; Lendor, C.; Rothman, P.B.; Miller, R.L. Antigen-specific immune responses to influenza vaccine in utero. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, A.L.; Følsgaard, N.V.; Vissing, N.H.; Birch, S.; Brix, S.; Bisgaard, H. Airway mucosal immune-suppression in neonates of mothers receiving a(H1N1)pnd09 vaccination during pregnancy. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Macpherson, A.J.; De Agüero, M.G.; Ganal-Vonarburg, S.C. How nutrition and the maternal microbiota shape the neonatal immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Agüero, M.G.; Ganal-Vonarburg, S.C.; Fuhrer, T.; Rupp, S.; Uchimura, Y.; Li, H.; Steinert, A.; Heikenwalder, M.; Hapfelmeier, S.; Sauer, U.; et al. The maternal microbiota drives early postnatal innate immune development. Science 2016, 351, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obanewa, O.; Newell, M.L. Maternal nutritional status during pregnancy and infant immune response to routine childhood vaccinations. Future Virol. 2017, 12, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftandelians, R.; Connor, J.D. Bactericidal antibody in serum during infection with Bordetella pertussis. J. Infect. Dis. 1973, 128, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingart, C.L.; Keitel, W.A.; Edwards, K.M.; Weiss, A.A. Characterization of bactericidal immune responses following vaccination with acellular pertussis vaccines in adults. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 7175–7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Weiss, A.A.; Patton, A.K.; Millen, S.H.; Chang, S.J.; Ward, J.I.; Bernstein, D.I. Acellular pertussis vaccines and complement killing of Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 7346–7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feikin, D.R.; Flannery, B.; Hamel, M.J.; Stack, M.; Hansen, P.M. Vaccines for Children in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. In Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 2): Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Assessing Infant Vaccine Responses in Resource-Poor Settings. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/723928_3 (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Diavatopoulos, D.A.; Mills, K.H.G.; Kester, K.E.; Kampmann, B.; Silerova, M.; Heininger, U.; van Dongen, J.J.M.; van der Most, R.G.; Huijnen, M.A.; Siena, E.; et al. PERISCOPE: Road towards effective control of pertussis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, e179–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.; Davis, M.M. New approaches to understanding the immune response to vaccination and infection. Vaccine 2015, 33, 5271–5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakaya, H.I.; Pulendran, B. Vaccinology in the era of high-throughput biology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Antunes, R.; Soldevila, F.; Pomaznoy, M.; Babor, M.; Bennett, J.; Tian, Y.; Khalil, N.N.; Qian, Y.; Mandava, A.; Scheuermann, R.H.; et al. Systems view of Bordetella pertussis booster vaccination in adults primed with whole-cell vs. acellular vaccine. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e141023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, N.P.; Gans, H.A.; Sung, P.; Yasukawa, L.L.; Johnson, J.; Sarafanov, A.; Chumakov, K.; Hansen, J.; Black, S.; Dekker, C.L. Preterm infants T cell responses to. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, V.; Locht, C. Mucosal Immunization Against Pertussis: Lessons From the Past and Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locht, C. Live pertussis vaccines: Will they protect against carriage and spread of pertussis? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, S96–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Apostolovic, D.; Jahnmatz, M.; Liang, F.; Ols, S.; Tecleab, T.; Wu, C.; van Hage, M.; Solovay, K.; Rubin, K.; et al. Live attenuated pertussis vaccine BPZE1 induces a broad antibody response in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2332–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnmatz, M.; Richert, L.; Al-Tawil, N.; Storsaeter, J.; Colin, C.; Bauduin, C.; Thalen, M.; Solovay, K.; Rubin, K.; Mielcarek, N.; et al. Articles Safety and immunogenicity of the live attenuated intranasal pertussis vaccine BPZE1: A phase 1b, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled dose-escalation study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerry, C.M.; Mahon, B.P. A Live, Attenuated Bordetella pertussis Vaccine Provides Long-Term Protection against Virulent Challenge in a Murine Model. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]